Library:The High Cost of Empire: Difference between revisions

More languages

More actions

(Updating parameter name) Tag: Reverted |

No edit summary Tag: Manual revert |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Library work|title=The High Cost of Empire|author=Michael Parenti|publisher=''[[The Progressive]]''|published_date=1981-11|published_location=[[City of Madison (Wisconsin)|Madison]], [[State of Wisconsin|Wisconsin]]|type=Magazine article| | {{Library work|title=The High Cost of Empire|author=Michael Parenti|publisher=''[[The Progressive]]''|published_date=1981-11|published_location=[[City of Madison (Wisconsin)|Madison]], [[State of Wisconsin|Wisconsin]]|type=Magazine article|source=https://archive.org/details/sim_progressive_1981-11_45_11/page/16/mode/2up}} | ||

'''''The High Cost of Empire''''' is an article by [[United States of America|Statesian]] political scientist [[Michael Parenti]], published in [[The Progressive|''The Progressive'']] in November 1981. In the article, Parenti accurately analyses how [[imperialism]] functions, but he also [[Whitewashing|whitewashes]] and minimises the role of the Statesian [[labour aristocracy]], who by and large support, participate in, and in many ways benefit from imperialism. | '''''The High Cost of Empire''''' is an article by [[United States of America|Statesian]] political scientist [[Michael Parenti]], published in [[The Progressive|''The Progressive'']] in November 1981. In the article, Parenti accurately analyses how [[imperialism]] functions, but he also [[Whitewashing|whitewashes]] and minimises the role of the Statesian [[labour aristocracy]], who by and large support, participate in, and in many ways benefit from imperialism. | ||

Latest revision as of 12:43, 30 September 2024

The High Cost of Empire | |

|---|---|

| Author | Michael Parenti |

| Publisher | The Progressive |

| First published | 1981-11 Madison, Wisconsin |

| Type | Magazine article |

| Source | https://archive.org/details/sim_progressive_1981-11_45_11/page/16/mode/2up |

The High Cost of Empire is an article by Statesian political scientist Michael Parenti, published in The Progressive in November 1981. In the article, Parenti accurately analyses how imperialism functions, but he also whitewashes and minimises the role of the Statesian labour aristocracy, who by and large support, participate in, and in many ways benefit from imperialism.

Text

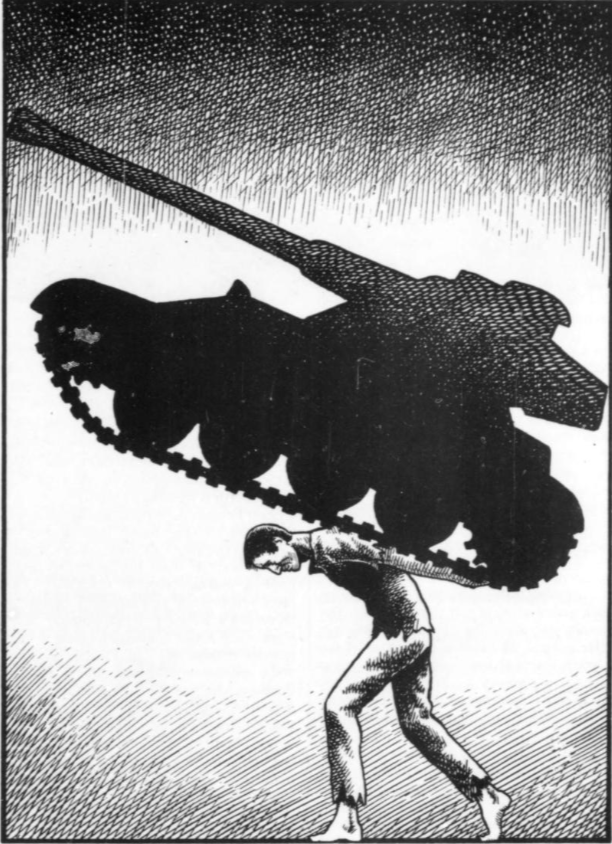

The growth of American corporations from modest domestic enterprises to multinational giants with vast overseas holdings has been matched by comparable growth in U.S. military establishment. Today, the United States is the greatest global military-industrial power in history. Sometimes the sword has intervened in other lands to protect the advantages won by the dollar, and sometimes the dollar has rushed in to enjoy the benefits extracted by the sword. Most impressive is the way American militarism and American capitalism have kept each other company in their travels abroad, and the way ordinary American taxpayers, consumers, and workers have had to sustain the heavy costs.

About 1.5 million U.S. military personnel are stationed in 116 countries. The United States has more than 400 major bases and almost 3,000 lesser ones situated in almost every region of the world, and it costs many billions of dollars yearly to maintain them. Almost $90 billion in military aid has been given to some eighty nations since World War II, and every variety of weapon is sold to foreign rulers by U.S. corporations (ably assisted by the Pentagon). Two million foreign troops and hundreds of thousands of foreign police and militia, under the command of various dictators and military juntas, have been trained, equipped, and financed by the United States, their purpose being not to defend their countries from outside invasion but to protect the ruling cliques from their own potentially insurgent populations.

Furthermore, U.S. corporations exert a controlling interest over the natural resources, land, labour, trade, finances, and markets of whole nations and, indeed, of whole continents. In sum, much of the world has been transformed into an American-equipped armed camp to preserve an American-dominated politico-economic status quo.

Years ago, the economist Kenneth Boulding, among others, noted that empires such as ours cost more than they are worth. Over a twenty-year period, the U.S. Government spent $2 billion to shore up a corrupt dictatorship in the Philippines, hoping to protect what amounts to a half-billion-dollar U.S. investment in that country. The same pattern holds true in other parts of the world: What we expend in aid and arms usually exceeds the value of the investments we hold. Therefore, Boulding and others reasoned, empires are losing propositions—irrational, self-defeating enterprises.

But are they really? Are they losing propositions for everyone? Who pays the costs and who reaps the benefits of empire? The truth is that those who profit handsomely from overseas investments and interventions are not the same as those who foot the bill. As Thorstein Veblen pointed out back in 1904, the gains of empire flow into the hands of the privileged business class, while the costs are extracted from "the industry of the rest of the people." The multinational corporations monopolise the returns while carrying little, if any, of the financial burden. The expenditures needed to make the world safe for ITT, Chase Manhattan, and General Augusto Pinochet of Chile are taken from the pockets of the people.

Is it really "our" profit from "our" oil and "our" tin, copper, bauxite, manganese, iron, gold, timber, and foods extracted from the land and labour of the Third World that we are protecting with our taxes and our sons?

In a recent book entitled Empire as a Way of Life, William Appleman Williams, the noted historian, scolds the American people for having become addicted to the conditions of empire. It seems "we" like empire. "We" live beyond our means and need empire as part of our way of life. "We" exploit the rest of the world and don't know how to get back to a simpler life. The implication is that "we" decided to send troops into Central America and Vietnam, and "we" thought to overthrow Salvador Allende in Chile, Mohammed Mossadegh in Iran, and Jacobo Árbenz in Guatemala. "We" urged the building of a global network of military and counterinsurgency bases. And "we" supported the Shah, trained the SAVAK tortures, and carpet-bombed Indochina.

In truth, however, ordinary Americans have seldom known about these things until after the fact, or—on those rare occasions when they were informed—have opposed intervention or have not given very enthusiastic support. Williams implies the imperialistic ideology and policy are a product of mass thinking; actually, it is the other way around: Mass thinking is a product of imperialist ideological manipulation and not always a reliable product—judging from the popular opposition to interventions in Vietnam and El Salvador.

Americans pay a heavy price in blood, sweat, and taxes for the U.S. military-industrial global empire. They pay in other ways, too. As more and more industry moves overseas, for example, attracted by the availability of cheap labour and high profits, more jobs are lost at home. More than a century ago, Karl Marx predicted that in an advanced stage, capitalism would export not only its goods but its very capital. So Ford Motor Company exports not only cars but whole factories to Argentina, which produce cars that are sold in that country and elsewhere. This means bigger profits for Ford but a higher unemployment rate for Detroit.

At the same time, the Argentina junta receives millions in aid from the U.S. taxpayers to keep Ford employees and other Argentine workers in line. Throughout the Third World, counterinsurgency and assassination squads trained and financed by the CIA and the U.S. military have terrorised and killed tens of thousands of trade unionists, workers, peasants, clergy, students, and other persons who have offered resistance to the oppressive social orders of those countries.

Nor do the benefits of this empire trickle down to the American consumer, as is often supposed. The radios assembled by women in Taiwan who work for twenty cents an hour, ten hours a day, six or seven days a week, do not cost much less than the transistors assembled in Ohio. Companies do not move to Taiwan in hope of saving money for the consumer, but to increase their own profits. They pay as little as they can in wages but still charge as much as they can in prices. That is why the returns on overseas investments are so much greater than on domestic investments.

The billions expended by the U.S. in non-military aid to other nations show a similar pattern, benefitting the overseas corporate investors, ruling oligarchs, generals, and big landowners, while offering little to the masses of the Third World. As someone once said, foreign aid is a matter of taking money from the poor people of a rich county and giving it to the rich people of a poor country.

The multinationals also cause a great deal of economic misery in the Third World—some of which comes home as a visitation upon our own people. Native lands are expropriated by agribusiness, for example, so that cash crops may be raised for export to more lucrative markets abroad, thus dispossessing the local peasantry. This has been the pattern throughout Latin America, with its teeming shanty towns and relatively empty countryside. Millions of destitute Latinos have been compelled to migrate to the United States, many of them illegally, to compete with American workers for low-income jobs that are becoming increasingly scarce. In effect, they have become a reserve army of labour helping to deflate wages at a further cost to American workers.

There are other ways Americans pay for "our" military-industrial empire. There is the distortion of an entire civilisation's technology and science as two-thirds of all research and development is controlled by the Pentagon. Small wonder we seem able to plan for monster science fiction wars in outer space while our trains are inferior to those we had forty years ago.

Americans pay for their empire with the cutbacks of vital human services, the neglect of environmental needs, the decay and financial collapse of our cities, the deterioration of our transportation, education, and health-care systems, and the devastating inflation that is inevitable when hundreds of billions of dollars are spent each year to produce and maintain a military colossus.

And on top of these there are the frightful social and psychological costs, the discouragement and decline of public morale, the growing anger, cynicism, and suffering of the poor and the not-so-poor, and the threatened imposition of authoritarian solutions.

As in Rome of old and in every empire since, the centre is bled in order to fortify the periphery. The treasure of the people is squandered so that patricians can pursue their far-off plunder. We suffer decay at home in order to better provide for "our" expanding global interests. It is a world made by and for the Pentagon and the multinational corporations.

What the military-industrialists fail to see is that the pyramid of power and profit they build rests on a crumbling base. Ultimately, no political-economic order can remain secure by victimising its own people. Sooner or later, this truth returns to haunt the mighty.