More languages

More actions

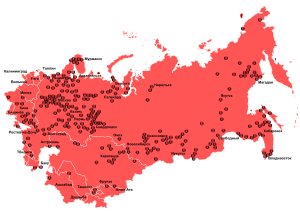

The Main Administration of Camps (Russian: Главное управление лагерей) abbreviated as GULag, was the system of prisons, remote camps, psychiatric hospitals and special laboratories that housed prisoners and fulfilled their penal sentences in the Soviet Union.

After the opening of the USSR archives in the early 1990s, it was confirmed most of the prisoners were convicted of regular crimes and were not political prisoners or counterrevolutionaries. At the peak of the GULag system, shortly after the Second World War in 1951, 2.4% of the adult Soviet population was entangled in the system in some way.[1][2] 20 to 40% of prisoners were released every year.[3]

Many gulags were mostly self-sufficient, especially the more remote ones. Most could be compared to small villages or towns, and the less accessible ones did not even need any enclosures such as fences or walls; inmates were free to move around the prison as they pleased. The belief in the USSR was that labour was rehabilitative, and thus putting inmates to work for their benefit as well as the benefit of the collective (the building of the Volga canal for example) was believed to help discourage people from committing crimes.[3]

History

Establishment

The GULag administration was established in 1919. The Soviet Union had inherited the katorga system of the Tsarist empire, including the existing infrastructure, and decided to use it as its basis for their own penal institution. In 1921, while the civil war ravaged the yet nascent USSR, we can observe the conditions of the Butyrka prison of Moscow: the prisoners organized the GUlag, they organized morning gymnastic sessions, founded an orchestra, a chorus, a library, and a club where they read foreign journals. There was a prisoners' council too, which occupied itself with the assignment of cells. One inmate remarked that they "strolled along the corridors as if they were boulevards," another one stating "Can’t they even lock us up seriously?"[4]

Purges

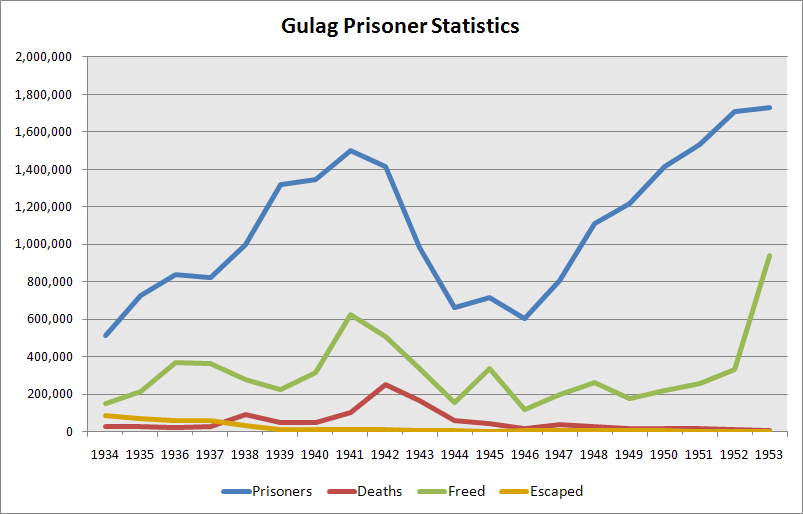

There were 510,307 gulag prisoners in 1934, including 127,000 to 170,000 political prisoners. The number of prisoners rose to 1,317,195 in 1939, and there were about 116,000 deaths in the camps.[5]

Second World War

During the Second World War, the gulag population peaked, as did its mortality rate. As the whole country was focused on a war economy and fighting a devastating invasion from Nazi Germany, sacrifices had to be made and many in the gulags felt it harshly (as did the civilian population).[5]

Post-war period

In 1953 and 1954, under his anti-Stalin campaign, Khrushchev released many gulag inmates under the guise of them being falsely convicted. After the opening of the USSR archives however, it was found most of those inmates were common criminals that were released back into the general population. In 1953, amnesty was given to 70% of the "ordinary criminals" of a sample camp studied by the CIA. Within the next 3 months, most of them were re-arrested for committing new crimes.[2]

Conditions

Working conditions

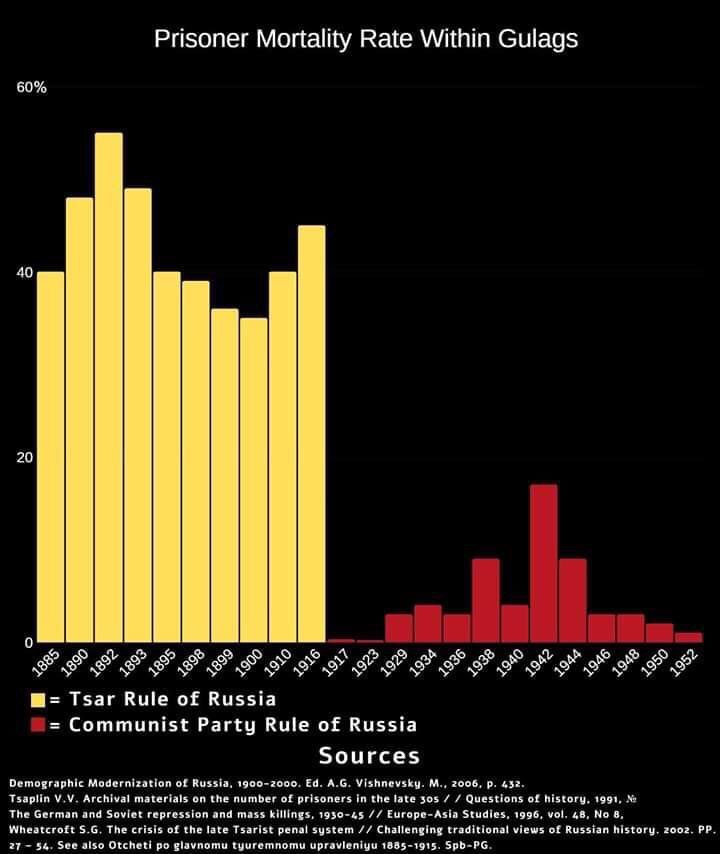

Inmates worked 10-hour days until 1954, when the work day was reduced to 8 hours. After 1954, Prisoners who worked very productively could have their sentences reduced by up to half and were given extra food or money.[6] The death rate in the gulags was highest during the Second World War, but was always lower than the death rate in the Tsarist prison camps that had existed before the revolution, which had a death rate of over 40%.[7]

Food

Until 1952, all prisoners received 122 grams of grain, 10 grams of flour, 20 grams of sugar, 75 grams of fish, 500 grams of potatoes and vegetables, 15 grams of fat, 45 grams of meat, and 650 grams of bread each day. Prisoners who overfulfilled the quota by 100% or more could receive extra bread and sugar.[6]

Deaths

On average, 4% of inmates died every year. This figure includes executions and people who died of natural causes. As the death rate was significantly higher during the Second World War, only 2.5% died each year during peacetime.[3]

In popular fiction

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, a counter-revolutionary antisemitic pogromist, spent some time in Gulags. After his release, he fled the USSR and wrote a fictional tale called The Gulag Archipelago to garner support and funding abroad. Notably, his wife Natalya said that:

The subject of Gulag Archipelago, as I felt at the moment when he was writing it, is not in fact the life of the country and not even the life of the camps but the folklore of the camps[8]

She also claimed that she typed part of the book for Aleksandr when they were still living together.[8]

References

- ↑ Saed Teymuri (2018-10-31). The Truth about the Soviet Gulag - Surprisingly Revealed by the CIA The Stalinist Katyusha. Archived from the original on 2019-04-01. Retrieved 2022-09-11.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Central Intelligence Agency (1957). Four reports covering various aspects of forced labor in the USSR from 1945 to 1955.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Austin Murphy (2000). The Triumph of Evil: 'The Documented Facts about Eastern Europe and Communism'. [PDF] Fucecchio: European Press Academic Publishing. ISBN 8883980026

- ↑ “The prisoners were allowed free run of the prison. They organized morning gymnastic

sessions, founded an orchestra and a chorus, created a “club” supplied with foreign journals and a good library. According to tradition―dating back to pre-revolutionary days―every prisoner left behind his books after he was freed. A prisoners’ council assigned everyone cells, some of which were beautifully supplied with carpets on the floors and walls. Another prisoner remembered that “we strolled along the corridors as if they were boulevards.” To Babina, prison life seemed unreal: “Can’t they even lock us up seriously?””

Domenico Losurdo, David Ferreira (2020). Stalin: The History and Critique of a Black Legend: 'The Complex and Contradictory Course of the Stalin Era; A Concentrationary Universe Full of Contradictions' (p. 128). [LG] - ↑ 5.0 5.1 Ludo Martens (1996). Another View of Stalin: 'The Great Purge' (p. 169). [PDF] Editions EPO. ISBN 9782872620814

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "Forced Labor Camps in the USSR" (1957-02-11). Central Intelligence Agency. Archived from the original on 2023-03-28. Retrieved 2023-07-01.

- ↑ Anatoly Vishnevsky (2006). The Demographic Modernization of Russia, 1900-2000 (p. 432). Moscow. ISBN 5983790420

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "Solzhenitsyn's Ex‐Wife Says ‘Gulag’ Is ‘Folklore’" (1974-02-06). New York Times.