"Yugoslavia" redirects here. For the kingdom, see Kingdom of Yugoslavia (1918–1941). For its successor rump state, see Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (1992–2003).

| Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia Социјалистичка Федеративна Република Југославија Socialistična Federativna Republika Jugoslavija | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1945–1992 | |||||||||||||||||||

Anthem: Hej, Slaveni ("Hey, Slavs") | |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Capital and largest city | Belgrade | ||||||||||||||||||

| Official languages | None (de jure) Serbo-Croatian (de facto) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Recognised national languages | Macedonian Serbo-Croatian Slovene | ||||||||||||||||||

| Dominant mode of production | Socialism | ||||||||||||||||||

| Government | Federal parliamentary socialist republic | ||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||

• Democratic Federal Yugoslavia formed | 29 November 1942 | ||||||||||||||||||

• SFRY proclaimed | 29 November 1945 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 31 January 1946 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 7 April 1963 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 21 February 1974 | |||||||||||||||||||

• Death of Josip Broz Tito | 4 May 1980 | ||||||||||||||||||

• 14th Congress of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia | 20-22 January 1990 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 26 June 1991 | |||||||||||||||||||

• Bosnia and Herzegovina secedes | 1 March 1992 | ||||||||||||||||||

• Federal Republic of Yugoslavia proclaimed | 27 April 1992 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||||||||

• Total | 255,804 km² | ||||||||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||||||||

• 2021 estimate | 23,229,846 | ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

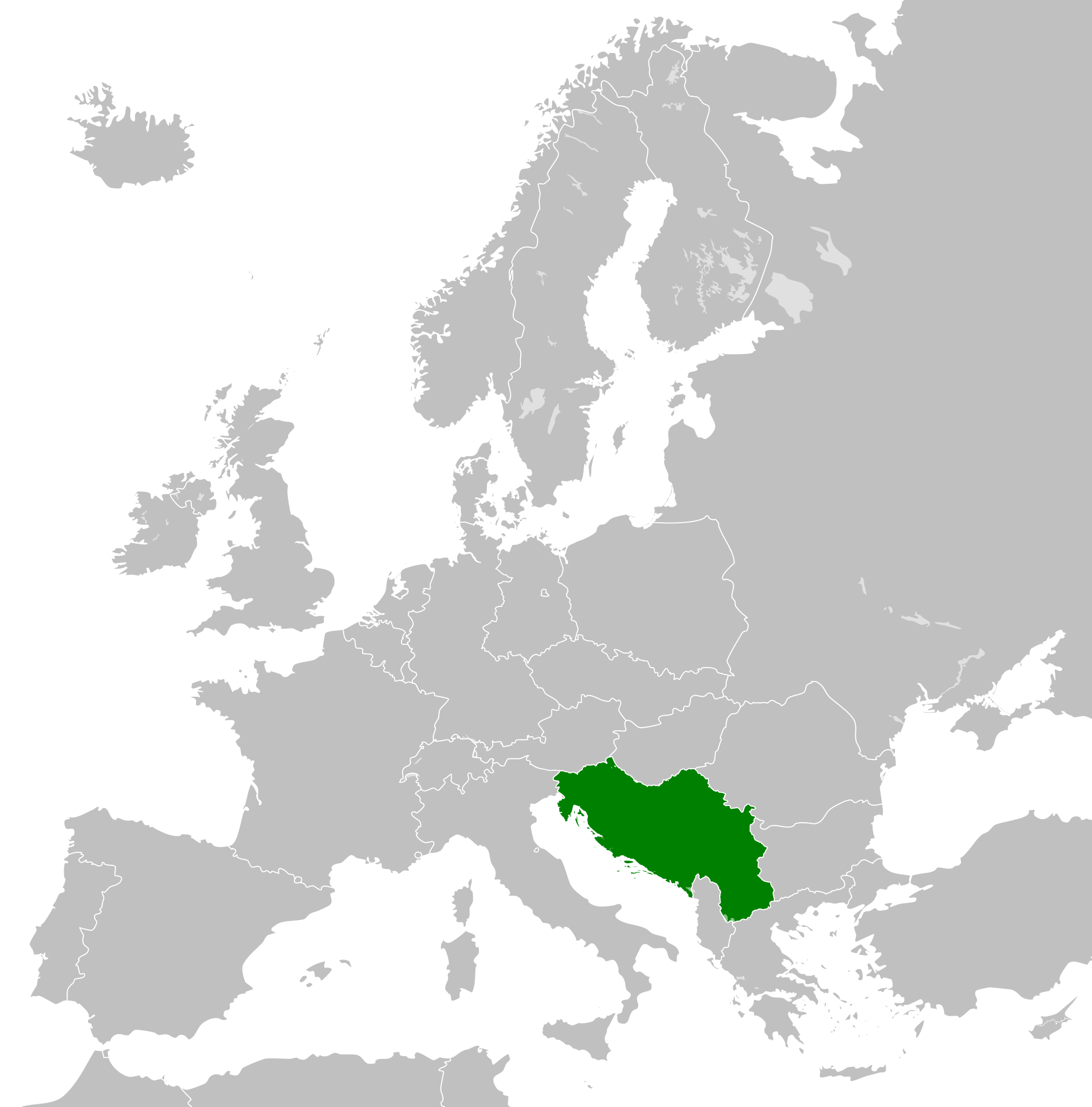

Yugoslavia, officially the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (SFRY; also SFR Yugoslavia or United Yugoslavia), was a non-aligned socialist state in the Balkans. It was a multi-ethnic federation that consisted of 28 nationalities.[1] The USA tolerated Yugoslavia's existence during the Cold War because it served as a buffer against the Warsaw Pact, but the United States turned against it soon after.[2]

History

Second World War

In April 1941, Yugoslavia was invaded by fascist armies from Germany, Italy, Hungary, Romania, and Bulgaria. The country was split into German and Italian zones of control. A partisan resistance movement began in the summer of 1941 and grew to an army of 800,000 by 1944, when the partisans and the Soviet Red Army liberated Belgrade.[3] The party grew from 12,000 at the start of the war to 148,000 at the end, but the new membership included some kulaks and petty bourgeois who had opposed the Nazis.[4]

Postwar period

After the war, the Council of National Liberation was established as the new organ of state power. In 1946, it created the People's Federative Republic of Yugoslavia with six republics and two autonomous regions, both in Serbia. The General Secretary of the ruling League of Communists of Yugoslavia was Josip Broz Tito. Other party leaders included Serbian Alexander Ranković, Montenegrin Milovan Djilas, and Slovenian Edvard Kardelj.

In June 1948, the Soviet Union and Eastern Bloc broke relations with Yugoslavia, disrupting its five-year plan and increasing its trade deficit.[3] Following the split, Tito began a purge against pro-Stalin elements of the party and arrested 100,000 to 200,000 people. He considered the USSR to be a mix of feudalism and state capitalism.[4]

In 1950, Yugoslavia began a policy of workers' self-management and passed a law stating that the means of production should be controlled by workers' councils.[3] Tito legalized buying and selling land in 1953.[4]

Yugoslavia hosted a meeting with Jawaharlal Nehru of India and Gamal Abdel Nasser of Egypt in 1956. They agreed to hold the founding meeting of the Non-Aligned Movement in Belgrade in 1961.[5]

Market socialism

In the 1960s, Yugoslavia moved to market socialism. The productive forces stayed in control of the state, but goods were produced and sold according to the market. By 1968, almost 80% of investment came from enterprises and banks. Market policies increased petty-bourgeois nationalism, especially in Croatia and Slovenia.[3]

In 1974, Yugoslavia adopted a new constitution that decentralized the government.[3]

Decline and IMF austerity

After Tito's death in 1980, the IMF imposed an austerity program on Yugoslavia, increasing unemployment.[3] The IMF and World Bank forced Yugoslavia to freeze wages, eliminate price subsidies and most worker-managed enterprises, and cut social spending. They decreased domestic production by allowing unlimited foreign capital into the country.[6] By 1991, unemployment had reached 20% and annual inflation was about 200%,[3] and the annual economic growth rate in 1990 was -10%.[6]

Yugoslav Wars

See main article: Yugoslav Wars

Croatia and Slovenia broke away from Yugoslavia in 1991 with support from the United States and Germany.[7] They were the most developed parts of Yugoslavia and had refused to subsidize the other republics.[8] Bosnia and Herzegovina broke away in April 1992, reducing Yugoslavia to only Serbia and Montenegro.[7]

Economy

From 1939 to 1975, income tripled and industrial development increased by nine times.[3] Between 1952 and 1979, Yugoslavia's economy grew by almost 400%. The economy began to stagnate after Tito's death.[9] The republics of Slovenia and Croatia and the autonomous province of Vojvodina were the most economically developed and had the highest per capita income. The southern areas of Montenegro, Macedonia, and Kosovo were the least developed, although the government subsidized more development in these regions.[3]

Large and medium-scale industry, transport, and banking were nationalized in Yugoslavia.[10] 60% of workers remained in the public sector as late as 1990. Citizens had a guaranteed right to an income and a month of paid vacation.[2]

Living standards

Healthcare

Yugoslavia had free medical care.[2] From 1939 to 1978, the number of hospital beds per 10,000 people increased from 19 to 60 and the number of physicians increased by 400%, while infant mortality decreased by 75%. Diphtheria, malaria, and typhus were also eliminated. 82% of the population was covered by health insurance.[11] From 1948 to 1981, the life expectancy increased from 53 years for women and 48.6 years for men to 73.2 and 67.7 years, respectively. By 1966, Yugoslavia's mortality rate decreased to 8.1 deaths per thousand people, which was lower than France or the UK at the time.[9]

Housing

Every year from the early 1960's to the 1980's, over 100,000 apartments were built and given to workers. By the late 1970's, all three-member worker households had electricity and almost all had plumbing.[9]

Literacy

From 1948 to 1981, illiteracy for ages ten and up decreased from 25.4% to 9.5%. In 1921, more than half of the adult population had been illiterate.[9]

References

- ↑ Michael Parenti (2000). To Kill a Nation: 'Hypocritical Humanitarianism' (p. 13). [PDF] Verso.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Michael Parenti (2000). To Kill a Nation: 'Third Worldization' (pp. 17–18). [PDF] Verso.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 Richard Becker (2005-10-01). "Yugoslavia: Nationalist competition opened door to imperialist intervention" Liberation School. Archived from the original on 2022-01-23. Retrieved 2022-06-21.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Ludo Martens (1996). Another View of Stalin: 'From Stalin to Khrushchev' (pp. 246–247). [PDF] Editions EPO. ISBN 9782872620814

- ↑ Vijay Prashad (2008). The Darker Nations: A People's History of the Third World: 'Belgrade' (p. 95). [PDF] The New Press. ISBN 9781595583420 [LG]

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Michael Parenti (2000). To Kill a Nation: 'Third Worldization' (pp. 20–21). [PDF] Verso.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Victor Penn (2009-03-31). "Yugoslavia: Ten years after the NATO massacre" Liberation News. Archived from the original on 2022-05-06. Retrieved 2022-09-09.

- ↑ Michael Parenti (2000). To Kill a Nation: 'Divide and Conquer' (p. 28). [PDF] Verso.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Latinka Perović, et al. (2017). Yugoslavia from a Historical Perspective. [PDF] Belgrade: Helsinki Committee for Human Rights in Serbia.

- ↑ Political Economy: 'The Economic System of the People's Democracies in Europe; The Character of the People's Democratic Revolution' (1954). [MIA]

- ↑ Muhamed Saric, Victor R. Godwin. The Once and Future Health System in the Former Yugoslavia: Myths and Realities. New York University.