More languages

More actions

Charhapiti (talk | contribs) No edit summary Tag: Visual edit |

Charhapiti (talk | contribs) mNo edit summary |

||

| Line 66: | Line 66: | ||

“No,” he answered simply. But I have never heard such poignant regret as his wonderful voice crowded into that single word. | “No,” he answered simply. But I have never heard such poignant regret as his wonderful voice crowded into that single word. | ||

Revision as of 17:21, 9 June 2024

The Sea-Serpent | |

|---|---|

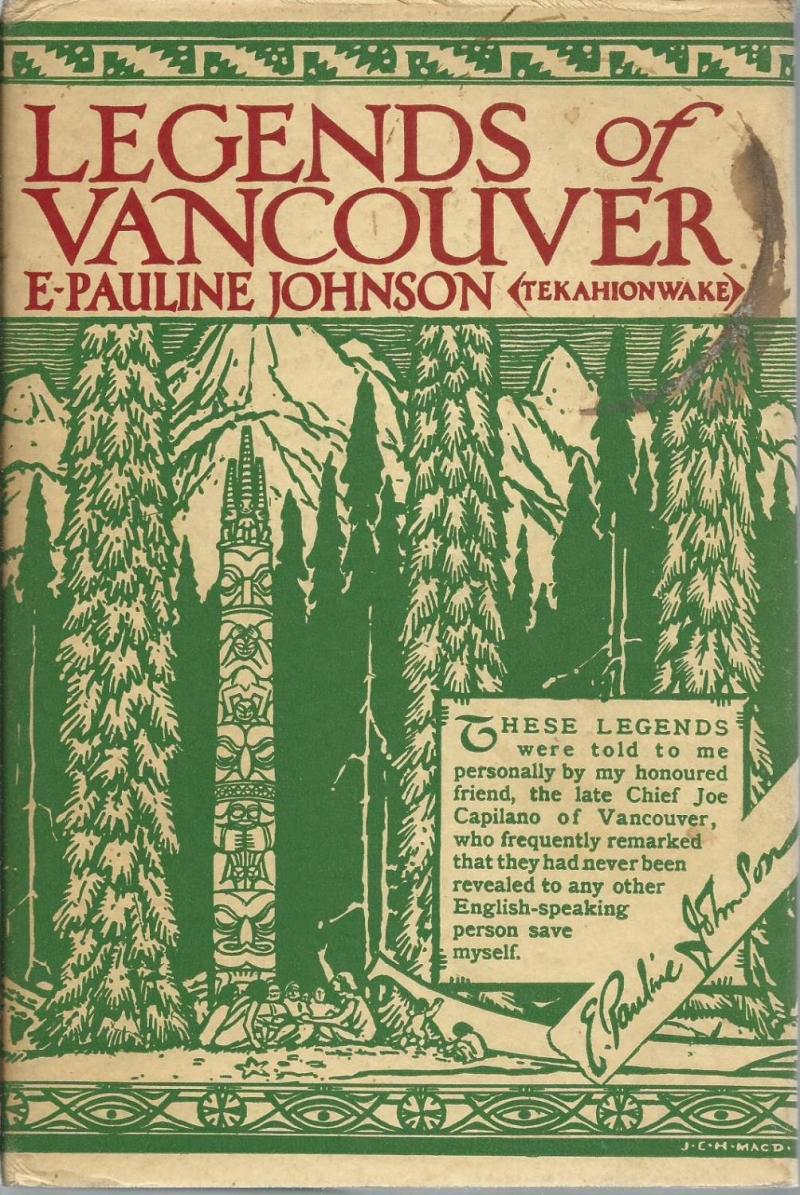

| Author | Tekahionwake (E. Pauline Johnson, Mohawk Nation) |

| First published | 1911 |

| Type | Book, Oral Narrative |

| Source | https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/3478/pg3478-images.html |

There is one vice that is absolutely unknown to the red man; he was born without it, and amongst all the deplorable things he has learned from the white races, this, at least, he has never acquired. That is the vice of avarice. That the Indian looks upon greed of gain, miserliness, avariciousness, and wealth accumulated above the head of his poorer neighbour as one of the lowest degradations he can fall to is perhaps more aptly illustrated than anything I could quote to demonstrate his horror of what he calls “the white man’s unkindness.” In a very wide and varied experience with many tribes, I have yet to find even one instance of avarice, and I have encountered but one single case of a “stingy Indian,” and this man was so marked amongst his fellows that at mention of his name his tribes-people jeered and would remark contemptuously that he was like a white man–hated to share his money and his possessions. All red races are born Socialists, and most tribes carry out their communistic ideas to the letter. Amongst the Iroquois it is considered disgraceful to have food if your neighbour has none. To be a creditable member of the nation you must divide your possessions with your less fortunate fellows. I find it much the same amongst the Coast Indians, though they are less bitter in their hatred of the extremes of wealth and poverty than are the Eastern tribes. Still, the very fact that they have preserved this legend, in which they liken avarice to a slimy sea-serpent, shows the trend of their ideas; shows, too, that an Indian is an Indian, no matter what his tribe; shows that he cannot, or will not, hoard money; shows that his native morals demand that the spirit of greed must be strangled at all cost.

The chief and I had sat long over our luncheon. He had been talking of his trip to England and of the many curious things he had seen. At last, in an outburst of enthusiasm, he said: “I saw everything in the world–everything but a sea-serpent!”

“But there is no such thing as a sea-serpent,” I laughed, “so you must have really seen everything in the world.”

His face clouded; for a moment he sat in silence; then, looking directly at me, said, “Maybe none now, but long ago there was one here–in the Inlet.”

“How long ago?” I asked.

“When first the white gold-hunters came,” he replied. “Came with greedy, clutching fingers, greedy eyes, greedy hearts. The white men fought, murdered, starved, went mad with love of that gold far up the Fraser River. Tillicums were tillicums no more, brothers were foes, fathers and sons were enemies. Their love of the gold was a curse.”

“Was it then the sea-serpent was seen?” I asked, perplexed with the problem of trying to connect the gold-seekers with such a monster.

“Yes, it was then, but–” he hesitated, then plunged into the assertion, “but you will not believe the story if you think there is no such thing as a sea-serpent.”

“I shall believe whatever you tell me, Chief,” I answered. “I am only too ready to believe. You know I come of a superstitious race, and all my association with the Pale-faces has never yet robbed me of my birthright to believe strange traditions.”

“You always understand,” he said after a pause.

“It’s my heart that understands,” I remarked quietly.

He glanced up quickly, and with one of his all too few radiant smiles, he laughed.

“Yes, skookum tum-tum.” Then without further hesitation he told the tradition, which, although not of ancient happening, is held in great reverence by his tribe. During its recital he sat with folded arms, leaning on the table, his head and shoulders bending eagerly towards me as I sat at the opposite side. It was the only time he ever talked to me when he did not use emphasizing gesticulations, but his hands never once lifted: his wonderful eyes alone gave expression to what he called “The Legend of the ‘Salt-chuck Oluk'” (sea-serpent).

“Yes, it was during the first gold craze, and many of our young men went as guides to the whites far up the Fraser. When they returned they brought these tales of greed and murder back with them, and our old people and our women shook their heads and said evil would come of it. But all our young men, except one, returned as they went–kind to the poor, kind to those who were foodless, sharing whatever they had with their tillicums. But one, by name Shak-shak (The Hawk), came back with hoards of gold nuggets, chickimin, everything; he was rich like the white men, and, like them, he kept it. He would count his chickimin, count his nuggets, gloat over them, toss them in his palms. He rested his head on them as he slept, he packed them about with him through the day. He loved them better than food, better than his tillicums, better than his life. The entire tribe arose. They said Shak-shak had the disease of greed; that to cure it he must give a great potlatch, divide his riches with the poorer ones, share them with the old, the sick, the foodless. But he jeered and laughed and told them No, and went on loving and gloating over his gold.

“Then the Sagalie Tyee spoke out of the sky and said, ‘Shak-shak, you have made of yourself a loathsome thing; you will not listen to the cry of the hungry, to the call of the old and sick; you will not share your possessions; you have made of yourself an outcast from your tribe and disobeyed the ancient laws of your people. Now I will make of you a thing loathed and hated by all men, both white and red. You will have two heads, for your greed has two mouths to bite. One bites the poor, and one bites your own evil heart; and the fangs in these mouths are poison–poison that kills the hungry, and poison that kills your own manhood. Your evil heart will beat in the very centre of your foul body, and he that pierces it will kill the disease of greed for ever from amongst his people.’ And when the sun arose above the North Arm the next morning the tribes-people saw a gigantic sea-serpent stretched across the surface of the waters. One hideous head rested on the bluffs at Brockton Point, the other rested on a group of rocks just below the Mission, at the western edge of North Vancouver. If you care to go there some day I will show you the hollow in one great stone where that head lay. The tribespeople were stunned with horror. They loathed the creature, they hated it, they feared it. Day after day it lay there, its monstrous heads lifted out of the waters, its mile-long body blocking all entrance from the Narrows, all outlet from the North Arm. The chiefs made council, the medicine-men danced and chanted, but the salt-chuck oluk never moved. It could not move, for it was the hated totem of what now rules the white man’s world–greed and love of chickimin. No one can ever move the love of chickimin from the white man’s heart, no one can ever make him divide all with the poor. But after the chiefs and medicine-men had done all in their power and still the salt-chuck oluk lay across the waters, a handsome boy of sixteen approached them and reminded them of the words of the Sagalie Tyee, ‘that he that pierced the monster’s heart would kill the disease of greed for ever amongst his people.’

“‘Let me try to find this evil heart, oh! great men of my tribe,’ he cried. ‘Let me war upon this creature; let me try to rid my people of this pestilence.’

“The boy was brave and very beautiful. His tribes-people called him the Tenas Tyee (Little Chief) and they loved him. Of all his wealth of fish and furs, of game and hykwa (large shell-money) he gave to the boys who had none; he hunted food for the old people; he tanned skins and furs for those whose feet were feeble, whose eyes were fading, whose blood ran thin with age.

“‘Let him go!’ cried the tribespeople. ‘This unclean monster can only be overcome by cleanliness, this creature of greed can only be overthrown by generosity. Let him go!’ The chiefs and the medicine-men listened, then consented. ‘Go,’ they commanded, ‘and fight this thing with your strongest weapons–cleanliness and generosity.’

“The Tenas Tyee turned to his mother. ‘I shall be gone four days,’ he told her, ‘and I shall swim all that time. I have tried all my life to be generous, but the people say I must be clean also to fight this unclean thing. While I am gone put fresh furs on my bed every day, even if I am not here to lie on them; if I know my bed, my body, and my heart are all clean I can overcome this serpent.’

“‘Your bed shall have fresh furs every morning,’ his mother said simply.

“The Tenas Tyee then stripped himself, and, with no clothing save a buckskin belt into which he thrust his hunting-knife, he flung his lithe young body into the sea. But at the end of four days he did not return. Sometimes his people could see him swimming far out in mid-channel, endeavouring to find the exact centre of the serpent, where lay its evil, selfish heart; but on the fifth morning they saw him rise out of the sea, climb to the summit of Brockton Point, and greet the rising sun with outstretched arms. Weeks and months went by, still the Tenas Tyee would swim daily searching for that heart of greed; and each morning the sunrise glinted on his slender young copper-coloured body as he stood with outstretched arms at the tip of Brockton Point, greeting the coming day and then plunging from the summit into the sea.

“And at his home on the north shore his mother dressed his bed with fresh furs each morning. The seasons drifted by; winter followed summer, summer followed winter. But it was four years before the Tenas Tyee found the centre of the great salt-chuck oluk and plunged his hunting-knife into its evil heart. In its death-agony it writhed through the Narrows, leaving a trail of blackness on the waters. Its huge body began to shrink, to shrivel; it became dwarfed and withered, until nothing but the bones of its back remained, and they, sea- bleached and lifeless, soon sank to the bed of the ocean leagues off from the rim of land. But as the Tenas Tyee swam homeward and his clean young body crossed through the black stain left by the serpent, the waters became clear and blue and sparkling. He had overcome even the trail of the salt-chuck oluk.

“When at last he stood in the doorway of his home he said, ‘My mother, I could not have killed the monster of greed amongst my people had you not helped me by keeping one place for me at home fresh and clean for my return.’

“She looked at him as only mothers look. ‘Each day, these four years, fresh furs have I laid for your bed. Sleep now, and rest, oh! my Tenas Tyee,’ she said.”

. . . . .

The chief unfolded his arms, and his voice took another tone as he said, “What do you call that story–a legend?”

“The white people would call it an allegory,” I answered. He shook his head.

“No savvy,” he smiled.

I explained as simply as possible, and with his customary alertness he immediately understood. “That’s right,” he said. “That’s what we say it means, we Squamish, that greed is evil and not clean, like the salt-chuck oluk. That it must be stamped out amongst our people, killed by cleanliness and generosity. The boy that overcame the serpent was both these things.”

“What became of this splendid boy?” I asked.

“The Tenas Tyee? Oh! some of our old, old people say they sometimes see him now, standing on Brockton Point, his bare young arms outstretched to the rising sun,” he replied.

“Have you ever seen him, Chief?” I questioned.

“No,” he answered simply. But I have never heard such poignant regret as his wonderful voice crowded into that single word.