More languages

More actions

Ethiopia, officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country in East Africa.

History

Overview

The History of Ethiopia can be usefully categorized into four periods:

- To 1270: Antiquity

- To 1500: The Ethiopian Middle Ages (which encompasses the beginning of the Zagwe Dynasty to the beginning of the emergence of Islam and the end of the early Solomonic period)

- To 1855: The Gondarine Period[1]

- To present day: The Modern Period (beginning with the End of the Zemene Mesafint, "the Era of Princes") under Tewdros II in 1855.[2]

Before 1270

1270–1500

1500–1855

1855–1974

Italy attempted to colonize Ethiopia in the 19th century but was defeated by Emperor Menelik's forces in 1896. Fascist Italy overthrew Emperor Haile Selassie and occupied Ethiopia from 1936 to 1941. Haile Sellasie was reinstated as Emperor and continued to rule the country until 1974. Starting from the 50s, the United States started to exert neocolonial relations in Ethiopia.[3]

1974–1991

In 1974, the Ethiopian Revolution took place, which ultimately brought the Derg to power. The Derg was chaired initially by Mengistu Haile Mariam (he was replaced by Aman Adom in September 1974), who later became head of state in 1977. The monarchy was formally abolished in 1975,[4] and replaced by a socialist government in Ethiopia. In 1987, the Derg was formally dissolved and the People's Democratic Republic of Ethiopia founded,[5] which was overthrown by the TPLF and other groups in 1991, establishing the Transitional Government of Ethiopia.[6]

1991–present

In 1995, the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia was founded.

Politics and government

Administrative divisions

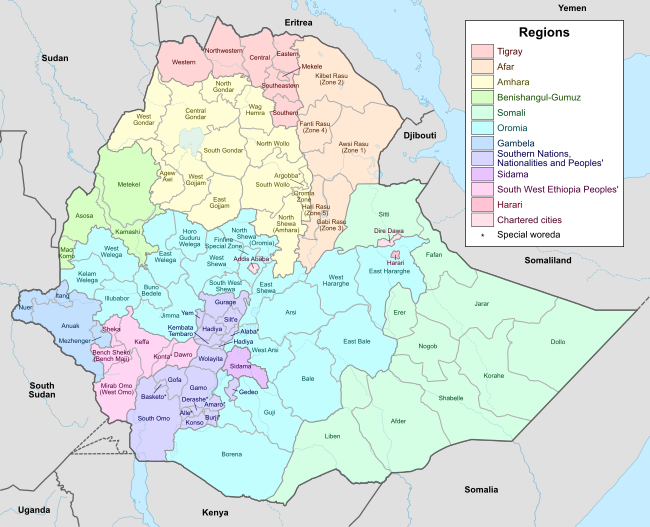

In 1992, the Transitional Government issued Proclamation 7/1992 (National/Regional Self-Government Establishment Proclamation), which was responsible for the creation of fourteen national/regional governments and two chartered cities. In 1995, five of the regions were merged to form the Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples.[7] Presently, there are eleven regions (kilil) based on ethno-linguistic territories:

- Afar

- Amhara

- Benishangul-Gumuz

- Gambela

- Harari

- Oromia

- Sidama

- Somali

- South West Ethiopias Peoples

- Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples

- Tigray

The two chartered cities are Addis Abeba and Dire Dawa. Regions are subdivided into zones (formely, meaning prior to 1991, this administrative level was called awrajja). Zones are subdivided in Woredas, which are further subdivided into Kebeles.[8]

The Woredas comprise three main organs: a council, an executive and a judicial. The Woreda Council is the highest government organ of the district, which is made up of directly elected representatives from each kebele in the woredas.

The main constitutional powers and duties of the Woredas are:

- Preparing and approving the annual Woreda development plans and budgets and monitoring their implementation

- Setting certain tax rates and collecting local taxes

- Administering fiscal resources of the Woreda

- Constructing and maintaining low-grade rural tracks and roads, water points, and Woreda level administrative infrastructure (offices, houses)

- Administering primary schools, health institutions and veterinary facilities

- Managing agricultural development activities, and protecting natural resources[8]

The representative of the people in each kebele is accountable to their electorate. The woreda chief administration is the district's executive organ that encompasses the district administrator, deputy administrator, and the head of the main sectoral executive offices found in the district, which are ultimately accountable to the district administrator and district council. The quasi-judicial tasks belong to the Security and Justice administration. In addition to woredas, city administrations are considered at the same level as the woredas. A city administration has a mayor whom members of the city council elected. As different regional constitutions govern woredas, the names of the bodies may differ.[9]

The Kebeles are the prime contact level for most Ethiopian citizens. Kebele administrations consist of an elected council (approx. 100 members), a Kebele Cabinet, and a social court (three judges). They commonly form community commitiees. The Kebele Cabinet usually comprises a manager, chairperson, development agents, school director, representatives from the womens association and youth association.

The Kebele council and executive committee's main responsibilites are:

- Preparing a Kebele devlopment plan

- Ensuring the collections of land and argicultural income tax

- Organizing local labor and in-kind contributions to development activities

- Resolving conflicts within the community (through social courts)[8]

Constitution and legal system

The Constitution of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia (Amharic: የኢትዮጵያ ፌዴራላዊ ዴሞክራሲያዊ ሪፐብሊክ ሕገ መንግሥት), also known as the 1995 Constitution of Ethiopia, is the supreme law of Ethiopia. The constitution came into force on 21 August 1995 after it was drawn up by the Constituent Assembly that was elected in June 1994. It was adopted by the Transitional Government of Ethiopia on 8 December 1994.[10]

The main features of Constitution of 1994 are:

- The establishment of the federal system: The Constitution declares Ethiopia to be a federal polity with nine regional states based on ethno-linguistic patterns. Federalism was introduced as the culmination to the long-standing 'national question'. The constitutions also outlines the relations between the federal government and the regions.

- Ethnicity is of great importance in the Constitution. The wording of the Preamble of the Constitution begins with "We, the nations, nationalities and peoples of Ethiopia. ..."[10] This symbolises a constitution of the Ethiopian citizens not simply taken together as a people but as citizens in their different ethnolinguistic groupings. The ethno-linguistic groupings and the nationality issue have historico-political and socio-economic significance beyond the cultural and linguistic expressions.

- The Constitution establishes a bicameral parliamentary democracy. There are two houses known as the Federal Houses. They are the House of Peoples' Representatives (HPR), with 547 seats, and the House of Federation (HF), with 108 seats. The Constitution also provides for a one house State Council at the state level. The HPR is the highest authority of the Federal Government and the State Council is the highest organ of state authority. The HF which is composed of representatives of Nations, Nationalities and people is the other representative assembly with specific power, including the ultimate "power to interpret the Constitution".

- The right to secession is part of the broader right to self- determination. The right to secession is the ultimate extension and expression of the right to self-determination and the Constitution provides a detailed set of procedures for the way in which this right may be exercised.

- The Constitution states that, "the right to ownership of rural and urban land … is exclusively vested in the state and in the people of Ethiopia". It goes on to add, "Land is a common property of the nations, nationalities and Peoples of Ethiopia and shall not be subject to sale or to other means of transfer". According to Article 40, Land is common property of the Ethiopian state and its people.[10]

- Article 5 provides both for the equality of languages and for their practical application in government. Accordingly, all 85 Ethiopian languages enjoy equal state recognition. It also allows for the right of nations to protect and develop the useage of its own language.[11]

- The ultimate interpreter of the Constitution is not the highest court of law, but the HF. The Constitution establishes the Council of Constitutional Inquiry, a body of mostly legal experts of high standing, headed by the Chief Justice of the Federal Supreme Court, to examine constitutional issues, and submit its findings to the House of Federation. The HF thus has the competent and authoritative legal advice of the Council of Constitutional Inquiry before it makes its decision on constitutional issues.[11]

Customary and religious law has a special status in Ethiopia, as well as in the federal states. This also finds application in the 1960 Civil Code.[12]

Ethnic federalism

Marxist Leninist Influence

Proponents of Ethnic Federalism

Criticism of Ethnic Federalism

Military

International relations

Economy

Education

Demographics

There are over 80 ethnic groups in Ethiopia. The largest nations in the country are the Tigray (6.1%) and Amhara (27%), who speak Semitic languages,and the Somalis (6.2%) and the Oromo (34%), who speak a Cushitic language.[3]

According to the most recent census conducted by the Population Census Commision of the FDRE in 2007 (which recorded a population of 74 million), 43,5% of the Ethiopian Population are Orthodox Christian (Tewahedo), 18.6% Protestant (mostly Pent'ay) and 0,7% Catholic, which totals to a Christian population of 62,8%.[13] In addition, 33.9% are Muslim,[13] 68% of which identify as Sunni, and 2% as Shia.[14] The census lists 2.6% of the population as being adherents to "traditional religions".[13]

Languages

Since the 29th of February 2020 (as decided by Ethiopia's Council of Ministers), the FDRE has five working languages: Afaan Oromo, Tigrinya, Somali, Afar and Amharic. Prior to this decision, Amharic was the only working language of Ethiopia, and it remains the de facto second language of many Ethiopians because of this status.[15] Amharic and Afaan Oromo are considered to be lingua francae of Ethiopia.[16] Ethiopia has a literacy rate of 52%.[17]

The 2007 census reported 85 Ethiopian ethnic groups vs. 80 of the 1994 census, and the 2007 census reported 87 Ethiopian mother tongues vs. 77 of the 1994 census.[18] However, this same paper also notes:

"the persistent difficulty concerning differences between names of languages and their dialects, and between self-names and names, often thought derogatory, given by others. Of course even the notions 'ethnic group', 'mother tongue' or 'language' are not well defined, but are non-discrete entities, and the facts which, in particular cases, would give them clarity if not satisfactory definition are many and probably impossible to elicit in a census. The Ethiopian census seems not trying to identify and count all Ethiopian ethnic groups and mother tongues, or even a well-defined subgroup of these. The apparent absence of expert advice in these matters (or at least in the census reporting) is understandable, given the certain difficulties of choosing among experts, interpreting the advice (probably often contradictory), and implementing it."[18]

The same author elswhere states about the 1994 Census:

"linguistic findings of the Census seem reasonably consistent with the typically un-quantified and often intuitive knowledge of Ethiopianist linguists" [despite of the] "expected difficulties for the Census arising from the political sensitivities associatied with linguistic and ethnolinguistic questions, an unsystematic and ambiguous linguistic nomenclature, and the practical problem of reaching and sampling in all corners of Ethiopia."[16]

indicating the census reliability. The Ethnologue page for Ethiopia lists 87 living and 2 extinct languages, broadly in the Afro-Asiatic (Semitic, Cushitic and Omotic languages) and Nilo-Saharan (Surmic, Gumuz, and Koman languages) language families (excluding sign language for Amharic).[17] Currently, 25 languages are used as a language of instruction in primary education,[19] whereas English is used as a language of instruction (Amharic and the local language being included in the curriculum) in secondary and higher education.[20] More precisely:

"Ethiopia’s approach has first and foremost been the introduction of local languages as a medium of instruction at the primary level and followed multilingual education strategies. Ethiopian educational experts of the several regions and zones decided whether the mother tongue should be used as a medium of instruction at the first cycle (1st– 4th grade) or during the complete primary level. That means that the medium of instruction can not only be different within a regional state but sometimes even within zones of a region with a multiethnic situation. Local languages are used as a medium of instruction up to the 8th grade in the Oromiya, Amhara, and Tigray regions as well as in Addis Ababa. The SNNP (Southern Nations, Nationalities and People) are using the respective local languages only in the first cycle (...). Amharic as a medium of instruction is preferred in urban areas due to the multiethnic character of many towns where the inhabitants often only share it as the lingua franca."[19]

The concrete usage of languages varies according to the existence or availability of written material in that language, a consistent and standardized dictionary and grammar, and the availability of trained and educated people in that respective language.[19]

Principally, according to the 1994 constitution (Article 5 and Article 39), each nation has the right to choose its respective working language, as well as the right to speak, to write and to develop its own language, as well as promote and preserve its own culture and history.[10]

Several Ethiopian langages use the Ge'ez Script (Ethiopic Script), first used to write the Ge'ez language, which presently serves as an liturgical language of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church. It is the script for the major Ethiosemitic languages, such as Tigrinya and Amharic. Some langages use different scripts, like for instance the Latin Script, such as Afaan Oromo, eventhough an alphasyllabic alternative exists since the 1950s in the form of the script invented by Sheikh Bakri Saṗalō.[21] In total, at least 20 languages use the Ethiopic script, including some Omotic and Nilo-Saharan languages. It is also employed for some Eritrean languages. It has 26 syllographs classes with 7 variations within a class, leading to a total of 182 syllographs in its standard form[22] (some languages use additional syllographs and there are additional "special" syllographs used in some contexts).

Politics of language and nationalities

The politics of language in Ethiopia broadly encompasses two related but distinct topics: a) Whether a policy of linguistic homogenization existed, and if so, to which extent, its role in "nation-building" efforts and the shift in policy in the 1990s as well as the political consequences of both and b) the politics of personal langauge choice and its instrumentalisation for political aims. I.e., the national-political and the economic problem, as well as the personal problem. Relatated to this is the problem of nationalities in Ethiopia, the emergence of ethnonationalism as a political force in Ethiopia etc.

Walleligne Mekonnen, marxist activist in the Ethiopian Student Movement, states in his (in)famous account of the problem of nationalities and languages in Ethiopia in the text "On the question of nationalities in Ethiopia":

"To be a "genuine Ethiopian" one has to speak Amharic, to listen to Amharic music, to accept the Amhara-Tigre religion, Orthodox Christianity and to wear the Amhara-Tigre Shamma in international conferences. In some cases to be an "Ethiopian", you will even have to change your name. In short to be an Ethiopian, you will have to wear an Amhara mask (to use Fanon's expression). Start asserting your national identity and you are automatically a tribalist, that is if you are not blessed to be born an Amhara. According to the constitution you will need Amharic to go to school, to get a job, to read books (however few) and even to listen to the news on Radio "Ethiopia" unless you are a Somali or an Eritrean in Asmara for obvious reasons. To anybody who has got a nodding acquaintenance with Marxism, culture is nothing more than the super-structure of an economic basis. So cultural domination always presupposes economic subjugation. A clear example of economic subjugation would be the Amhara and to a certain extent Tigrai Neftegna system in the South and the Amhara-Tigre Coalition in the urban areas." [23]

Walleligne Mekonnen is here referring to the 1955 Constitution, which adopted Amharic as the offical language of the Empire of Ethiopia.[24] In this quote, the political importance of language in Ethiopia is described and its content can be used as a useful starting point. The contentiousness of the history of state formation in Ethiopia is well described in this quote:

"The history of state formation in Ethiopia is a source of profound contention. At one extreme, pan-Ethiopian nationalists contend that the state is some 3,000 years old. According to this perspective, well represented by Solomon Gashaw, the state has existed for millennia, successfully countering ethnic and regional challenges, and forging a distinct national identity. The assimilation of periphery cultures into the Amhara or Amhara/Tigray core culture made the creation of the Ethiopian nation possible. From this point of view, Ethiopia is a melting pot and a nation-state. At the other extreme, ethnonationalist groups such as the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF) claim that Abyssinia (central and northern Ethiopia, the geographic core of the Ethiopian polity) colonized more than half the territories and peoples to form a colonial empire in the last quarter of the nineteenth century. From their vantage point, Ethiopia is a colonial empire that needs to undergo decolonization whereby ‘‘ethnonational’’ colonies become independent states. A more credible image of Ethiopia would be as a historically evolved (noncolonial) empire - state. The ancient Ethiopian state—short-term contractions in size notwithstanding—expanded, over a long historical period, through the conquest and incorporation of adjoining kingdoms, principalities, sultanates, and so on, which is indeed how most states in the world were formed."[25]

Here, three of the dominant views on Ethiopian state formation, both scholarly and politically, are outlined. The History of the politics of languages and nationalities will be examined in more detail in the following sections, as it has undergone dramatic shifts in the modern history of Ethiopia.

1855-1974

1975-1991

Post 1991

References

- ↑ Harold G. Marcus (2002). A History of Ethiopia: Updated Edition: 'Chapter 2: The Golden Age of the Solomonic Dynasty, to 1500' (pp. 17-29). London: University of California Press. [LG]

- ↑ Bahru Zewde (2002). A History of Modern Ethiopia (1855-1991) (p. 21). Addis Abeba: Addis Abeba University Press. [LG]

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Solyana Bekele (2021-08-09). "Smash neocolonialism in Ethiopia, erase the fake borders!" The Burning Spear. Archived from the original on 2022-07-29. Retrieved 2022-08-27.

- ↑ Bahru Zewde (2002). A History of Modern Ethiopia (1855-1991) (pp. 233-251). Addis Abeba: Addis Abeba University Press.

- ↑ Stefan Brüne (1990). IDEOLOGY, GOVERNMENT AND DEVELOPMENT - THE PEOPLE’S DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF ETHIOPIA (p. 193). Northeast African Studies, vol. 12, no. 2/3,. doi: 10.2307/43660324 [HUB]

- ↑ Paul B. Henze (2004). Layers of Time: A History of Ethiopia (p. 330). Addis Abeba: Shama Books. [LG]

- ↑ Mulatu Wubneh (2017). Ethnic Identity Politics and the Restructuring of Administrative Units in Ethiopia (p. 127). International Journal of Ethiopian Studies, Vol. 11, No. 1 & 2, Special Issue.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Sedar Yilmaz and Varsha Venugopal (2008). Local Government and Accountability in Ethiopia (pp. 4-6). [PDF] International Studies Program Working Paper 08-38.

- ↑ László Vértesy and Teketel Lemango Bekalo (2022). Comparision of local governments in Hungary and Ethiopia (pp. 66-75). [PDF] De iurisprudentia et iure publico: Journal of Legal and Poltical Sciences, Vol. XIII, No. 1-2. doi: 10.5281/zenodo.7341351 [HUB]

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Ethiopia's Constitution of 1994 (1995). [PDF] Federal Negarit Gazeta - No.1 21st August.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Ameha Wondirad (2013). An overview of the Ethiopian Legal System (pp. 95-98). [PDF] NZACL, Faculty of Law, Victoria University Wellington.

- ↑ Tsegaye Beru (2013). A Brief History of the Ethiopian Legal Systems - Past and Present (pp. 339-340). [PDF] International Journal of Legal Information, Vol.41.3, Duquesne University School of Law Research Paper No. 2017-07.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Population Census Commission (2008). Summary and Statistical Report of the 2007 Population and Housing Census: Population Size by Age and Sex (p. 17). [PDF] United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA).

- ↑ "THE WORLD’S MUSLIMS: UNITY AND DIVERSITY" (2012-08-09). Pew Research Centre. Archived from the original. Retrieved 05.20.2023.

- ↑ Abdul Rahman Alfa Shaban (2020-04-03). "One to five: Ethiopia gets four new federal working languages" africanews. Archived from the original on 2020-15-10. Retrieved 2023-20-05.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Grover Hudson (2004). Languages of Ethiopia and Languages of the 1994 Ethiopian Census (p. 160). [PDF] Hamburg: Aethiopica (7): International Journal of Ethiopian and Eritrean Studies , 160-172. doi: https://doi.org/10.15460/aethiopica.7.1.286 [HUB]

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 "Ethiopia". Ethnologue. Retrieved 2023-05-20.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Grover Hudson (2012). Ethnic Group and Mother Tongue in the Ethiopian Censuses of 1994 and 2007 (pp. 204-205). [PDF] Hamburg: Aethiopica (15):International Journal of Ethiopian and Eritrean Studies, 204-215. doi: https://doi.org/10.15460/aethiopica.15.1.666 [HUB]

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Katrin Seidel and Janine Moritz (2009). Changes in Ethiopia’s Language and Education Policy – Pioneering Reforms? (pp. 1126-1127). [PDF] Trondheim: Proceedings of the 16th International Conference of Ethiopian Studies.

- ↑ Stefan Trines (2018-11-15). "Education in Ethiopia" World Education News+ Reviews. Retrieved 2023-05-21.

- ↑ Ronny Meyer (2016). The Ethiopic script: linguistic features and socio-cultural connotations (pp. 137-160). Oslo: Multilingual Ethiopia: Linguistic Challenges and Capacity Building Efforts, Oslo Studies in Language 8(1), 137-172.

- ↑ Gabriella F. Scelta (2001). The Comparative Origin and Usage of the Ge’ez writing system of Ethiopia (p. 4). [PDF] Boston University.

- ↑ Walleligne Mekonnen (1969). On the Question of Nationalities in Ethiopia (p. 2). [PDF] Addis Abeba.

- ↑ Jan ZÁHOŘÍK and Wondwosen TESHOME (2009). DEBATING LANGUAGE POLICY IN ETHIOPIA (p. 87). [PDF] ASIAN AND AFRICAN STUDIES, 18, 1, 80-102.

- ↑ Alem Habtu (2005). Multiethnic Federalism in Ethiopia: A Study of the Secession Clause in the Constitution (pp. 320-321). Publius: The Journal of Federalism, Volume 35, Issue 2, 313-335. doi: 10.1093/publius/pji016 [HUB]