More languages

More actions

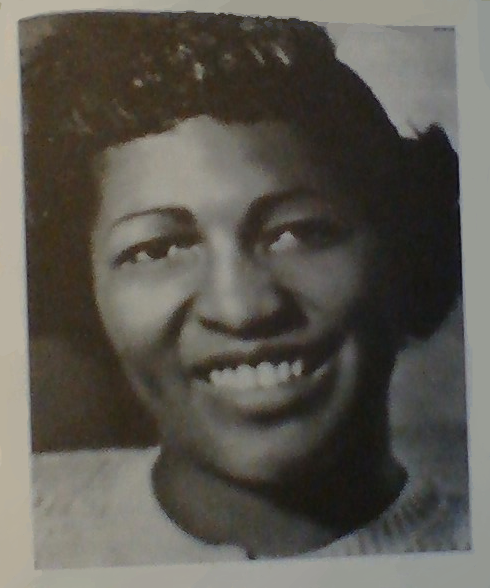

Claudia Jones was a feminist, Black-liberationist intellectual and organiser for the Communist Party of the United States of America (CPUSA), and, following her deportation from the USA for advocating communism, was founder of the West Indian Gazette newspaper and the Caribbean Carnival in London, England.

Claudia was born in Port-of-Spain, Trinidad on February 21, 1915. At age 8 she emigrated with her family to the United States, where her mother worked in the garment industry and her father as a journalist, likely for the West Indian American in Harlem, New York City.[1] Her experience of racism in the United States, as well as her mother's early death from spinal meningitis at age 37, while Claudia was still in her late teens, and which Claudia attributed to overwork and the poor conditions of life as an immigrant garment worker, motivated Claudia into political activism. In 1935 and 1936 she was writing a column, "Claudia's Comments" for a Black newspaper, editing a youth paper, organizing against the legal persecution of the Scottsboro Boys, and attending Harlem rallies. In 1936 she joined the Communist Party of the United States of America and its Young Communist League. Her rise within the Party was steady and by the late 1940s she was its major theoretician on women's issues and a member of its National Committee. In "Half the World", her regular Sunday column in the CPUSA newspaper, Daily Worker, as well as in other writings for the Party, she formulated radical Black feminist positions which helped guide a small feminist vanguard in her day and which would be echoed by later generations of feminists, especially Black feminists, in the 1960s and 1970s. Among her contributions were an exploration, along with other Black leftists like Maude White and Louise Thompson Patterson, of the intersections between race, class, and gender which placed Black American women under what CPUSA publications called a "triple burden" or "triple oppression" on account of their simultaneous occupation of three subaltern positions: female, racial minority, and working class. The circumstances of this group and their corresponding economic "super-exploitation" made them, in Claudia's view, a key population in the anti-imperialist and anti-capitalist struggle; and among her Party comrades she consistently advocated the importance of the Black woman to their project:

Who more than the Negro woman, the most exploited and oppressed, belongs in our Party? To win the Negro women for full participation ... to bring her militancy ... to even greater heights in the current and future struggles against Wall Street imperialism, progressives must acquire political consciousness as regards her special oppressed status.[2]

Another of Claudia's contributions, perhaps facilitated by her early experience of racialisation as well as her immersion within the Harlem renaissance of the 1920s, was her presentation of an expanded conception of United States race relations; she easily transcended blinkered, local, or parochial formulations of Black women's issues and instead was able to situate them within international race relations, imperialism, and the global division of labour. Her biographer Carole Boyce Davies describes her as an early formulator of an anti-imperialist, transnational feminism.[3]

Claudia's internationalist orientation developed even further after her expulsion from the United States. By 1942 if not before, she was under "aggressive surveillance"[4] by the United States Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) because of her prominence within the Communist Party. In January 1948 she suffered her first arrest and a brief imprisonment on Ellis Island under the 1918 Immigration Act. Deportation proceedings were begun against her. In October 1950 she was arrested again and imprisoned at Ellis Island and the New York City Women's Prison, this time under the Internal Security Act of 1950 (McCarran Act) which is directed against, among others, "(G) Aliens who write or publish, or cause to be written or published, or who knowingly circulate, distribute, print, or display, or knowingly have in their possession for the purpose of circulation, publication, or display, any written or printed matter, advocating or teaching opposition to all organized government, or advocating (I) the overthrow by force or violence or other unconstitutional means the Government of the United States ... or (v) the economic, international and governmental doctrine of world communism...."[5] She made bail after about a month, but a deportation order was served on her. Claudia had applied for US citizenship when she was 23 and again during her 7 year marriage to US citizen Abraham Scholnik, but her applications, after years of delay, had been denied;[6] she was thus always even more vulnerable to legal persecution than other American progressives. In June 1951 she was again arrested, this time under the Alien Registration Act of 1940 (Smith Act), along with 16 other CPUSA members. She made bail ($20,000) after about a month but in January 1953 was convicted and sentenced to a year and a day. Around this time she began suffering from hypertensive cardiovascular disease and was hospitalized after a heart attack. She began serving her sentence in January 1955 at the Women's Penitentiary in Alderson, West Virginia, was released early for "good behaviour" in October, but ordered deported on December 5th. On December 9th she boarded the Queen Elizabeth, seen off by more than 50 people including her father and her sister, bound for London, England to attempt, at age 40, to put down new roots and resume a free life.

In England she was welcomed by friends, including earlier communist deportees from the United States, and members of the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB). She was quickly admitted into the CPGB, but never achieved the status within that party that she had enjoyed in the CPUSA, possibly because her internationalist positions could be regarded as too close to a Mao Zedong-type line, which was not compatible with the position of the CPGB's top leaders. Carole Boyce Davies believes also that sexism and racism within the British left and the Party hindered her rise. Claudia's years in Great Britain are noteable mainly for activities outside the Party in the West Indian, African, and Asian immigrant communities in London. In 1957 she founded the West Indian Gazette (later the West Indian Gazette and Afro-Asian Caribbean News), a paper in which she and her romantic and political partner of the period, Abhimanyu Manchanda, invested much energy over the next several years. Filling a void left by the demise of the Caribbean Labour Congress's Caribbean News in 1957, the Gazette was the most influential and perhaps only Caribbean newspaper in London during its period of operation. Published weekly, the Gazette in its heyday was a complete newspaper with film and book reviews, sports news, popular information, major political news and analyses, and an editorial page.[7] Its editorial stance was anti-capitalist and anti-imperialist, and it took up the cause of the then-proposed West Indian Federation as a step toward full independence for the Caribbean colonies. It provided a forum for the views of West Indian intellectuals, informed the Black community about upcoming cultural events and performances by West Indian artists, and helped the colonial immigrants in London cohere into a self-conscious and self-respecting community.[8]

In 1958 Claudia organised the first Caribbean Carnival in London. Inspired by the outdoor Carnivals with music, dancing, and costumes that had been held for many years in the West Indies, the London Carnival was intended to provide the immigrant community a heart warming and unifying celebratory occasion, as well as an opportunity for friendly and positive engagement with their white neighbours. These things were much needed at that moment because the Notting Hill race riots, which shocked and disoriented the West-Indian-Afro-Asian community in London, had just occurred. The London Carnival became a yearly event, held initially indoors with occasional outdoor forays, because it was timed to coincide with the Trinidadian Carnival and thus took place in winter.

Essential elements in the first London Caribbean Carnivals included masqueraders, steelband musicians (Trinidad All Stars, Dixielanders), live brass bands, calypsonians (Mighty Terror, Sparrow, and Lord Kitchener).

Another important element of the carnival was the carnival queen competition, and the crowning of the carnival queen. There were also Caribbean dance companies such as Boscoe Holder and Troupe, bongo dancers, tambour bamboo, limbo dancing, and a "jump-up." The carnivals were recorded by the BBC and transmitted to the Caribbean, and televised coverage still marks carnival celebrations in the Caribbean. Photographs reveal huge dancing crowds of attendees. (Carole Boyce Davies, p 180.)

In 1965, the regular Carnival did not occur, because of Claudia's death in December 1964, but that summer, Carnival activities took place in the streets and became the Notting Hill Carnival which continues to this day, attracting more than a million people annually, and claiming to be the biggest street festival of popular culture in Europe.[9]

Claudia believed that economics, politics, and culture are inextricably linked.[10] She had conflict with some in the CPGB and other leftists over the idea that things such as carnival, dances, and beauty pageants were relevant to political work.[11] According to Carole Boyce Davies, Claudia Jones "determined that culture, as a series of normative practices, was an important tool in the community's development as in larger political and economic struggles as a whole" (p 175). Regarding the Carnival, Carole adds that:

Still within the context of Marxism-Leninism, therefore, Jones was drawn to those aspects of culture that lent themselves to community joy and social transcendence of the given conditions of people's experience, that is, their material culture. Thus putting in place the celebratory, in this case, was an act of cultural affirmation. — P 175.

Although her level of activity remained high during her years in England, Claudia's health was by this time not entirely robust. Some of the problems that had begun during her ordeal in the US justice system lingered, and it should also be noted that she had been diagnosed with tuberculosis when she was 19 and committed at that time to a sanatorium for almost a year because of it.[12] In 1956 she was hospitalized in London for three months.[13]

Despite these problems and her work load, Claudia was able to make three interesting trips abroad during the last years of her life. In 1962 she visited the Soviet Union on an invitation from the women's magazine, Soviet Women.[14] She toured Leningrad, Moscow, and Sevastapol, studying developments in health care and visiting a school. She spent some time as a patient at Rossia Sanatorium in Yalta, Crimea, during this trip. Two of her poems, "Storm at Sea", and "Paean to Crimea", were written at the sanatorium. She returned to London on November 21, and described her trip in glowing terms for the West Indian Gazette in December:

I wanted to see for myself the first Land of Socialism; to meet its people, to see for myself the growth of its society, its culture, its technological and scientific advance. I was curious to see a land which I already knew abhorred racial discrimination to the extent of making it a legal crime and where the equality of all people is a recognized axiom.

In 1963 she visited the Soviet Union again, this time to represent Trinidad and Tobago at the World Congress of Women. Finally, in 1964, she went to Japan as a delegate to the 10th World Conference against Hydrogen and Atom Bombs, and to China as a guest of the China Peace Committee. This was a very fulfilling trip for her. At the Tokyo conference, she served as Vice Chair of the Drafting Committee, and proposed a resolution in support of liberation struggles in the third world.[15] And in China she met the country's leader, Mao Zedong, as part of a Latin American delegation, and interviewed several leading women of the Chinese revolution, including Soon Ching Ling, who was Vice Chairman of the People's Republic of China and the widow of Sun Yat-Sen.[16] Another high point of her time in China was a visit to Yenan, the area in Northern China where the Communists had regrouped after their Long March, living ascetically among the peasants as "fish among water" and gradually building popular sympathy for their cause. The visit inspired another poem from Claudia, "Yenan – Cradle of the Revolution", which enthusiastically recounts the principles and achievements of the Chinese Communists in that era.

The fight to win and

Change the mind of Man

Against the corruption of centuries

Of feudal-bourgeois, capitalist ideas

The fusion of courage and clarity

Of polemic against misleaders

Back in London, Claudia wrote about her meeting with Soon Ching Ling in what would be one of her last pieces for the West Indian Gazette and Afro-Asian Caribbean News: "First Lady of the World: I Talk with Mme Sun Yat-Sen" (November 1964). The article describes some of the considerable social and economic achievements that had been made in China in the 15 years since the Revolution, including the People's Communes, which Claudia and Soon Ching Ling had discussed at length.[17]

Claudia Jones died in London in December 1964. Governments and progressive groups around the world sent messages and made diplomatic representations, including those by Raymond Kunene of the African National Congress and ambassador H.E.L. Khefila of the Democratic Republic of Algeria, both of whom officiated at her Memorial service at Saint Pancras Town Hall on February 27, 1965. She was cremated and her ashes buried in Highgate Cemetary beside the grave of Karl Marx. In 1984 a headstone was erected there, inscribed with her dates of birth and passing, and the words:

Valiant fighter against racism and imperialism who dedicated her life to the progress of socialism and the liberation of her own black people

Name and nativity

Claudia was born in Belmont, and grew up in Woodbrook, Port-of-Spain. Her mother was Sybil (Minnie Magdalene) Cumberbatch (née Logan) and her father was Bertrand Cumberbatch. Claudia's original name was Claudia Vera Cumberbatch. She started using the last name Jones in her late teens or early twenties, likely as a way to shield her identity from state agents and others opposed to her activism. Her parents emigrated to the United States two years before she did; she, along with sisters Lindsay, Irene, and Sylvia, and aunt Alice Glasgow, joined them in February 1925 in New York.

The following little piece of material from William J Maxwell's book New Negro, Old Left describes some of the culture and ideas in the Harlem of Claudia's youth:

"Concurrent with the nationalization of African America in the early twentieth century grew an internationalizing imagining of blackness, institutionalized in the United States by the Pan-Africanism of W.E.B. Du Bois, one founder of the nationalized NAACP, and by Marcus Garvey's immensely popular Universal Negro Improvement Association, or UNIA (accent on the `Universal'). Many of this imagining's eminent architects, including Garvey himself, were Caribbean newcomers to Harlem, the `Negro Metropolis' that absorbed about two-thirds of those who doubled the nation's immigrant black population between 1900 and 1910. Schooled under English, French, Dutch, or Spanish colonialisms, thrown together in the packed black city within a city, migratory black intellectuals clashed over much but jointly regarded the oppression of blacks as a transnational ill requiring transnational remedies. — Pp 20-1.

CPUSA

(This section is to describe her CPUSA period.)

Although she held ranking positions within the Communist Left, Jones maintained close connections to the grass roots. She regularly spoke and canvassed on Harlem street corners. In addition, she came to know black communist leaders in the Southern Negro Youth Congress (SNYC). These included Esther Coooper, James Jackson, Dorothy Burnam, Louis Burnham, Augusta Jackson, and Ed Strong.

Other works

- Ajamu Nangwaya, 2016. "Claudia Jones: Unknown Pan-Africanist, Feminist, and Communist". Telesur Pambazuka

- Carole Boyce Davies, 2008. Left of Karl Marx: The Political Life of Black Communist Claudia Jones

- William J Maxwell, 1999. New Negro, Old Left

Notes

- ↑ Carole Boyce Davies, p 92

- ↑ "An End to the Neglect of the Problems of Negro Women", pp 41-2, quoted in Carole Boyce Davies, p 40.

- ↑ Page 56

- ↑ Carole Boyce Davies, p xxiv

- ↑ Pub. L. No. 831, Chap. 1024, p. 1002; quoted in Carole Boyce Davies, p 141.

- ↑ Carole Boyce Davies, p 147

- ↑ Carole Boyce Davies, p 87

- ↑ The West Indian Gazette "was meant to be a primary information organ for the Caribbean community and to serve the role of political educator for a community that was beleaguered, scattered, uninformed, and subject to racial oppression, including racial violence" (Carole Boyce Davies, p 172).

- ↑ Carole Boyce Davies, p 180

- ↑ Carole Boyce Davies, p 174

- ↑ Carole Boyce Davies, p 175

- ↑ Carole Boyce Davies, p xxiii

- ↑ Carole Boyce Davies, p xxvi

- ↑ Carole Boyce Davies, p 223.

- ↑ Carole Boyce Davies, p xxvi

- ↑ Carole Boyce Davies, p 226

- ↑ Carole Boyce Davies, p 226