More languages

More actions

Why China Has No Inflation | |

|---|---|

| Author | Peng Kuang-hsi |

| Source | massline.org |

This is a pamphlet published by the Foreign Languages Press in Peking (Beijing) in 1976, during the Mao era. The complete text of the pamphlet is given here, although the collection of photographs of people at market places, etc., which was included in the original pamphlet, is omitted here. —Scott H.

An Introduction

ALL OVER the world, the capitalist economy is in turmoil. Ordinary people and their families are haunted daily by inflation. How to get rid of the menace has become a most widely discussed problem in many parts of the world. In sharp contrast is the situation in the People’s Republic of China. In the quarter of a century since its founding, thanks to the continuous growth of China’s socialist economy based on the policy of independence and self-reliance, and to the full display of mass initiative, the people’s livelihood has steadily improved. A remarkable feature in this respect is the stability of Renminbi [RMB] (People’s Currency)—the Chinese yuan.

How did China overcome the aftermath of the runaway inflation that prevailed on the eve of the liberation? Why is her currency immune from the monetary crises that have wrecked the capitalist world in all these years? How does the stability of RMB affect the daily life of her people? Answers are given in this booklet, based on a survey by the writer who had visited a number of families, checked with markets and interviewed government departments in charge of finance, banking and commerce.

These facts are presented in the hope that they may help the foreign reader to a better understanding of New China’s financial and monetary systems, her economic policy and the life of her people.

1. People Are Free from Inflation Worries

MONEY IS an indispensable medium in daily life. Through it we obtain food, clothing and so on. This is true of every country in our era of monetary economies. Therefore, ups and downs in the value of money are of concern to everyone. Yet people I spoke to during this survey gave little thought to possible changes in the value of RMB. Many housewives don’t even know what “inflation” means.

Why? At the Statistical Bureau of the Peking Municipality, a table attracted my attention.

| Year | 1965 | 1966 | 1968 | 1970 | 1973 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| For Goods | 100 | 100.22 | 100.52 | 101.32 | 101.57 |

| For services | 100 | 102.23 | 102.52 | 102.52 | 103.20 |

These figures tell us that 100 yuan at their 1965 value could buy 101.57 yuan worth of goods in 1973; and in services (rent, water, electricity, bus fare, etc.) they could buy 103.20 yuan worth. Thus, the value of the yuan is not only stable, but shows a slight upward trend.

The Peking scene is representative of the whole country. China’s yuan remains stable today despite the inflation raging in the entire capitalist world.

Stable Price Level; Improving Livelihood

The level of prices is an important indicator of a nation’s economy. It reflects the purchasing power of money, and serves as a yardstick of the people’s livelihood. Below is a worker’s family budget in China.

The Chang Family’s Budget

“You see, food, clothing and other necessities have cost the same all these years,” the 36-year-old textile worker Chang Pao-chih said to me when we talked of what he spends. “My family doesn’t have a high standard of living, but our income covers our needs and we don’t worry that our money will buy less.” His words clearly demonstrate the stability of prices in China, which in turn contributes to a secure life for her people.

Chang is a production team leader in a workshop of the Peking No. 2 State Textile Mill. His wife Chang Shu-hua, also 36, tends a cone-winding machine there. Their combined monthly income is 154 yuan. They have two children, one in primary school, the other in a day-nursery. The Changs breakfast and dine at home and lunch in the factory’s dining hall, which is located near their home. They are a rather typical family in China.

For an understanding of the impact of price level on the life of the people, I tabulated the family budget of the Changs.

| Item | 1965 | 1970 | 1974 |

| Grain | 23.60 | 25.45 | 25.45 |

| Meat, vegetables, etc. | 22.50 | 30.00 | 30.00 |

| Dining out | 12.00 | 12.00 | 12.00 |

| Sugar, fruit and refreshments | 10.00 | 10.00 | 9.50 |

| Clothing | 16.75 | 21.35 | 21.35 |

| Rent | 0.84 | 0.84 | 0.84 |

| Water | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.30 |

| Electricity | 1.05 | 1.05 | 1.05 |

| Gas | 1.60 | 1.60 | 1.60 |

| Bus fare, stamps | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.96 |

| Recreation | 1.20 | 1.20 | 1.20 |

| Haircuts, baths | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.50 |

| Day-nursery | 3.50 | 3.50 | 3.50 |

| Contingent outlays | 5.00 | 5.00 | 5.00 |

| Total | 99.80 | 113.75 | 113.25 |

Apart from spending on food and clothing, which increased in these ten years due to the birth and growth of the children, all other amounts have remained the same. So the family is able to put aside more than 40 yuan a month in the bank. With this money, the Changs have bought a radio, a TV set, two wrist watches and some furniture. Their home is adequately furnished.

On Sundays, they all have their meals at home, and the groceries cost about 2 yuan. What do they get for this money? According to Peking retail prices from 1965 to November 1974, 2 yuan could buy the following:

| Item | 1965 | 1974 |

|---|---|---|

| Eggs | 0.25 kg | 0.25 kg |

| Ribbon fish | 1.00 kg | 1.00 kg |

| Bean curd | 0.50 kg | 0.50 kg |

| Cabbages | 0.50 kg | 0.50 kg |

| Potatoes | none | 0.50 kg |

| Green onions | none | 0.50 kg |

That is to say, their food basket was a little heavier in 1974 for the same amount of money, reflecting the stability of prices.

Groceries Cost the Same

In Peking’s grocery stores and markets, price lists painted on boards in red, blue or white ink years ago are still unchanged. At the counters one may often hear a child sent to shop calling out:

“A kilogramme of salt, please.”

“Half kilo of soybean sauce, please.”

The child is used to the price, puts down the required cash, and goes off with the purchases without worrying about any error.

Most Peking grocery store prices have remained the same for years. And some have gone down a bit. This is shown by a survey for November, 1974, as compared with 1970 and 1965.

| Item | 1965 | 1970 | 1974 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pork | 2.00 | 1.80 | 1.80 |

| Mutton | 1.42 | 1.42 | 1.42 |

| Beef | 1.50 | 1.50 | 1.50 |

| Dressed chicken | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 |

| Ribbon fish | 0.86 | 0.80 | 0.80 |

| Eggs | 2.08 | 1.80 | 1.80 |

| Bean curd | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.16 |

| Cabbages | 0.058 | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| Potatoes | 0.24 | 0.24 | 0.20 |

| Green onions | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.18 |

Peking is amply supplied with vegetables at all seasons. The big markets at Tungtan, Hsitan, and Chaoyangmen carry more than 100 varieties for most of the year, and over 50 even in winter. Residents hailing from the south can find vegetables once peculiar to their regions but now grown in people’s communes in Peking’s outskirts, as are some foreign species including the sunset hibiscus of Africa, the lettuce of Europe and America, the coffee senna of Southeast Asia and a type of rape indigenous to Japan.

Average daily per capita consumption of fresh vegetables in Peking is 0.5 kilogramme, or double the level of the period immediately following the liberation. Seasonal adjustments are made in vegetable prices, but the average, in the past ten years, has stayed around 0.08 yuan per kilogramme. Staples like tomato and Chinese cabbage, when in season, are piled in huge heaps along the streets, and sold at 0.10 yuan per 2-3 kilogrammes.

All types of bean products in cakes, sheets, shreds, pulp and many other forms, much favoured by Peking’s consumers, sell at prices unchanged since 1956.

Prices of Other Daily Necessities Stable, a Few Marked Down

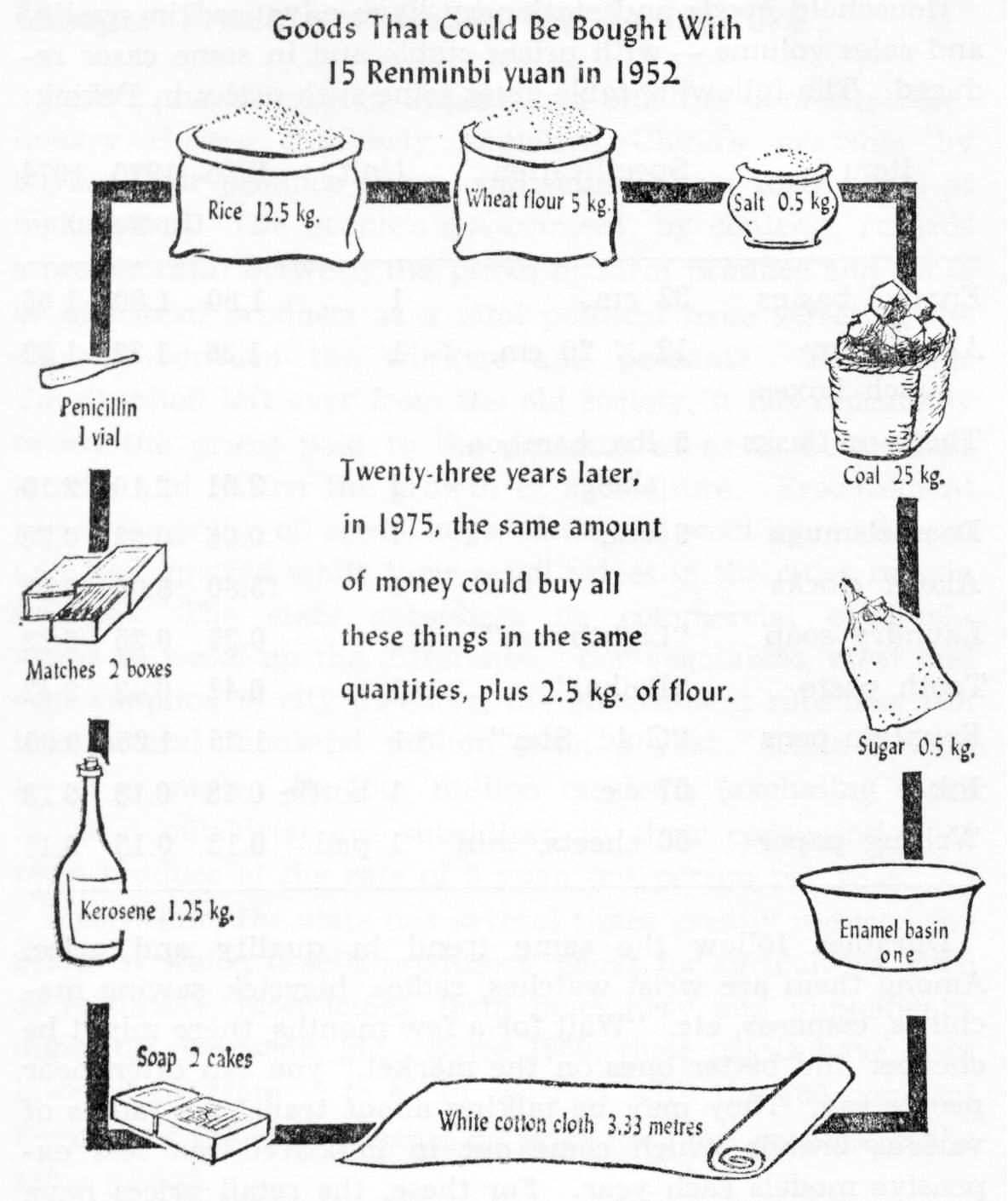

As we have seen from the Chang family budget, prices of grain and fuel in 1974 were still the same as in 1965. Moreover, they have been stable since the years immediately following liberation. For a sampling of goods that could be bought with 15 yuan in 1952 in Peking’s markets, see the diagram [immediately below].

Now, 23 years later, for the same amount of money one can obtain all these things in the same quantities, plus 2.5 kilogrammes of flour.

The system of state purchasing and marketing of grain was set up in 1953. Since then, to increase the income of the peasants, the state has several times raised its purchase prices for grain, while keeping its retail prices in the towns at approximately the same level. China’s consumers are also immune from the present upward trend of grain prices on the world market. The average retail prices for grain staples in China today are, for example: wheat flour (medium grade), 0.36 yuan per kilogramme; and rice, 0.286 yuan per kilogramme. They are virtually the same as the state’s purchase price paid to the producers. All costs of storage and transportation and the losses in the course of handling by commercial departments are covered by a state subsidy which amounts to about 2.5 million yuan for every 50 million kilogrammes (50,000 metric tons) of grain.

For clothing, cotton materials are available in increasing variety, and sales of woollen, silk, and synthetic piece goods have increased quickly. Staple items such as drills, cotton gabardines, and calico (printed and plain white) have not varied in price. For instance, the price of 1chih (1/3 metre) of plain white calico in Peking, Tientsin and Shanghai, has for yers been 0.28 yuan—equivalent to that of a pack of common cigarettes.

Household goods and stationery have advanced in quality and sales volume—with prices stable and in some cases reduced. The following table gives some such prices in Peking: