No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 79: | Line 79: | ||

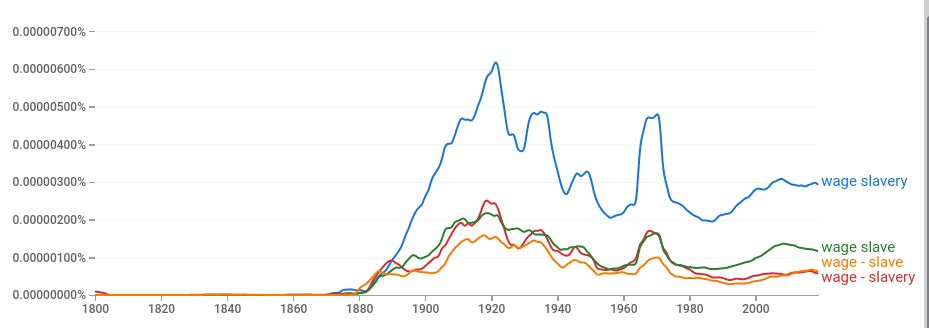

[[File:wage_slavery_ngram_frequency.jpg|thumb|300px|In Google's sample of English-language books the frequency of use of the terms "wage slave", "wage slavery", "wage-slave", and "wage-slavery" becomes significant around 1870 and peaks around 1920]] | [[File:wage_slavery_ngram_frequency.jpg|thumb|300px|In Google's sample of English-language books the frequency of use of the terms "wage slave", "wage slavery", "wage-slave", and "wage-slavery" becomes significant around 1870 and peaks around 1920]] | ||

[[Noam Chomsky]] has said that: | |||

[[Noam Chomsky]] has said that | :As long as individuals are compelled to rent themselves on the market to those who are willing to hire them, as long as their role in production is simply that of ancillary tools, then there are striking elements of coercion and oppression that make talk of democracy very limited, if even meaningful…<ref>Interview at [http://www.chomsky.info/interviews/19760725.htm Chomsky.info</ref> | ||

===General historical points=== | ===General historical points=== | ||

Revision as of 15:10, 13 May 2022

Wage slavery is a term for wage labour which emphasises the unfree aspects of that labour. "Wage slavery" and similar terms have been in use almost as long as capitalist wage labour has existed. For example, in 1818 an English cotton worker described the cotton manufacturers as "despotic" masters who ruled over the "English Spinner slave."[1] This worker also employed an analysis later used by Karl Marx and others, that the wage woker is unfree because he cannot escape the necessity of working for some capitalist master in order to survive:

It is vain to insult our common understandings with the observation that such men are free; that the law protects the rich and poor alike, and that a spinner can leave his master if he does not like the wages. True; so he can; but where must he go? why to another to be sure.

— English cotton worker, 1818

By the time Marx had entered university, similar ideas were current in Germany. Marx's law lecturer, Eduard Gans wrote in 1836 that a visit to the English factories showed that "slavery is not yet over, that it has been formally abolished, but materially is completely in existence."[2]

Use of the wage slavery concept by Marx

Marx used the idea of wage slavery at least as early as in his Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844, in which he wrote that workers are forced to "carry out slave-labour, completely giving up their freedom, in the service of greed."[3]

In 1847 Marx noted, as others had before, that the slave had some advantage over the wage worker in being more valuable to the master or less easily replaced:

The slave is sold once and for all; the proletarian must sell himself daily and hourly. The individual slave, property of one master, is assured an existence, however miserable it may be, because of the master's interest. The individual proletarian, property as it were of the entire bourgeois class which buys his labor only when someone has need of it, has no secure existence.

— Karl Marx, The Principles of Communism 1847

In "Wage Labour and Capital" (1849), he wrote that "the relation of wage labour to capital, [is] the slavery of the worker, the domination of the capitalist."[4]

Marx argued that although the wage labourer is not owned by any particular capitalist she or he is, in effect, owned by the capitalist class. In "Wage-Labour and Capital" he wrote that because the worker's "sole source of livelihood is the sale of his labour, [he] cannot leave the whole class of purchasers, that is, the capitalist class, without renouncing his existence. He belongs not to this or that bourgeois, but to the bourgeosie, the bourgeois class."[5]

In Das Kapital (1867) Marx even says that because of this structural domination over the worker,

the worker belongs to capital before he has sold himself to the capitalist.

— Marx Engels Collected Works, volume 35, p. 577.

Marx also discusses the unfree aspects of wage labour at various other points in Capital, volume 1:

[Wage labour], which cannot get free from capital, and whose enslavement to capital is only concealed by the variety of individual capitalists to whom it sells itself, [forms] an essential of the reproduction of capital itself.

— Capital, Vol. 1, Chap. 25, Section 1, paragraph 5.[6]

The Roman slave was held by chains; the wage-labourer is bound to his owner by invisible threads. The appearance of independence is maintained by a constant change in the person of the individual employer, and by the legal fiction (fictio juris) of a contract.

— Karl Marx, Capital, volume 1, book 1: 'The Process of Production of Capital'

In Theories of Surplus Value (1861-63), Marx noted that the French writer Simon Linquet had made the necessity argument already in 1767:[7]

The slave was precious to his master because of the money he had cost him… They were worth at least as much as they could be sold for in the market… It is the impossibility of living by any other means that compels our farm labourers to till the soil whose fruits they will not eat… It is want that compels them to go down on their knees to the rich man in order to get from him permission to enrich him… what effective gain [has] the suppression of slavery brought [him ?] He is free, you say. Ah! That is his misfortune… These men… [have] the most terrible, the most imperious of masters, that is, need. … They must therefore find someone to hire them, or die of hunger. Is that to be free?

— Simon Linguet, Théorie des lois civiles, etc., p. 467.

Use or misuse in defence of actual slavery

Before the American Civil War, Southern defenders of African American slavery invoked the concept of wage slavery to favorably compare the condition of their slaves to workers in the North.[8][9] Some argued that workers were "free but in name – the slaves of endless toil," and that their slaves were better off.[10]

Some modern historians have given evidence in support of these views. According to Fogel and Engerman plantation records show that slaves worked less, were better fed and whipped only occasionally—their material conditions in the 19th century being "better than what was typically available to free urban laborers at the time".[11] According to another study, slaves in the United States in the 19th century had improved their standard of living from the 18th century.[12] According to Mark Michael Smith of the Economic History Society, slaves could sometimes manipulate the master-slave relationship enough to "carve out a degree of autonomy"[13]

Many abolitionists in the U.S., including northern capitalists, regarded the notion of wage slavery to be spurious,[14] saying that wage workers were "neither wronged nor oppressed".[15]

Abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison stated that the use of the term "wage slavery" (in a time when chattel slavery was still common) was an "abuse of language."[16]

Abraham Lincoln and the republicans "did not challenge the notion that those who spend their entire lives as wage laborers were comparable to slaves", though they argued that the condition was different, as laborers were likely to have the opportunity to work for themselves in the future, achieving self-employment.[17]

In 1869 The New York Times described the system of wage labor as "a system of slavery as absolute if not as degrading as that which lately prevailed at the South".[17]

History

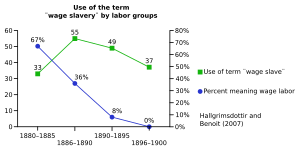

Use of the term wage slavery correlates partly with the shift during the 19th century from artisinal labour to factory labour which was more regimented and in which the worker had less autonomy.

England

The Marxist historian E.P. Thompson has argued that the working-class' complaint during the 19th century industrial revolution in England was not reducible to a decline in material well-being. What mattered to workers was how the conditions of their work had changed - that their working life was now characterized by overwork, monotony, discipline, and most importantly the loss of freedom and independence. Thompson thus observed that 'People may consume more goods and become less happy or less free at the same time.'[18]

Thompson noted that for British workers at the end of the 18th and beginning of the 19th centuries, the "gap in status between a 'servant,' a hired wage-laborer subject to the orders and discipline of the master, and an artisan, who might 'come and go' as he pleased, was wide enough for men to shed blood rather than allow themselves to be pushed from one side to the other. And, in the value system of the community, those who resisted degradation were in the right." [19]

Accoding to economist William Lazonick, "Research has shown that the 'free-born Englishman' of the eighteenth century – even those who, by force of circumstance, had to submit to agricultural wage labour – tenaciously resisted entry into the capitalist workshop."[20]

United States

In the United States the term "wage slavery" was widely used by labor organizations during the mid-19th century, but was gradually replaced by the term "wage work" towards the end of the 19th century.[21]

In the 1830s the Lowell Mill Girls condemned the "degradation and subordination" of the newly emerging industrial system[23][24]

and expressed their concerns in a protest song during their 1836 strike:

- Oh! isn't it a pity, such a pretty girl as I

- Should be sent to the factory to pine away and die?

- Oh! I cannot be a slave, I will not be a slave,

- For I'm so fond of liberty,

- That I cannot be a slave.[25]

Noam Chomsky has said that:

- As long as individuals are compelled to rent themselves on the market to those who are willing to hire them, as long as their role in production is simply that of ancillary tools, then there are striking elements of coercion and oppression that make talk of democracy very limited, if even meaningful…[26]

General historical points

According to Encyclopedia Britannica, the range of occupations and status positions held by chattel slaves has been nearly as broad as that held by free persons. This could be interpreted as indicating some similarities between chattel slavery and wage slavery.[27]

Anthropologist David Graeber says the first wage labor contracts we know about—whether in ancient Greece or Rome, or in the Malay or Swahili city states in the Indian ocean—were in fact contracts for the rental of chattel slaves (usually the owner would receive a share of the money, and the slave, another, with which to maintain his or her living expenses.) Such arrangements were quite common in New World slavery as well, whether in the United States or Brazil. The Black liberationist and Marxist C. L. R. James contended that most of the techniques of human organization employed on factory workers during the industrial revolution were first developed on slave plantations.[28]

Psychological effects of wage labour

Investigative journalist Robert Kuttner in Everything for Sale, analyzes the work of public-Health scholars Jeffrey Johnson and Ellen Hall about modern conditions of work, and concludes that "to be in a life situation where one experiences relentless demands by others, over which one has relatively little control, is to be at risk of poor health, physically as well as mentally." Accoding to Kuttner, "Epidemiological data confirm that [under wage labor], lower-paid, lower-status workers are more likely to experience the most clinically damaging forms of stress, in part because they have less control over their work."[29]

It has also been contended that wage labour "implies erosion of the human personality… [because] some men submit to the will of others, arousing in these instincts which predispose them to cruelty and indifference in the face of the suffering of their fellows."[30]

Erich Fromm noted that if a person perceives himself as being what he owns, then when that person loses (or even thinks of losing) what he "owns" (e.g. the good looks or sharp mind that allow him to sell his labor for high wages), then, a fear of loss may create anxiety and authoritarian tendencies because that person's sense of identity is threatened. In contrast, when a person's sense of self is based on what he experiences in a state of being (creativity, ego or loss of ego, love, sadness, taste, sight etc.) with a less materialistic regard for what he once had and lost, or may lose, then less authoritarian tendencies prevail. The state of being, in his view, flourishes under a worker-managed workplace and economy, whereas self-ownership entails a materialistic notion of self, created to rationalize the lack of worker control that would allow for a state of being.[31]

Methods of control in wage systems

In 19th century discussions of labor relations, it was normally assumed that the threat of starvation forced those without property to work for wages. Proponents of the view that modern forms of employment constitute wage slavery, even when workers appear to have a range of available alternatives, have attributed its perpetuation to a variety of social factors that maintain the hegemony of the employer class.[32][33] These include efforts at Manufacturing Consent and eliciting false consciousness.

Bourgeois-ideological opposition to the concept

Philosopher Gary Young has argued that the same basic reasoning that considers the individual to be forced to sell his labor to a capitalist in order to survive, also applies to the capitalist in that he is forced to hire a worker to survive otherwise his capital will be exhausted through consumption, leaving him nothing to purchase the necessities of life.[34] In this sense, the capitalists depend on the workers as the workers depend on the capitalists.[35]

Austrian economics argues that a person is not "free" unless they can sell their labor because otherwise that person has no self-ownership and will be owned by a "third party" of individuals.[36]

See also

Other works

- Bruno Leipold, 2022. "Chains and Invisible Threads: Liberty and Domination in Marx's Account of Wage Slavery". Chapter of a larger book by Leipold. Chapter available from Academia.edu with email registration.

References

- ↑ Bruno Leipold, pp 194-5.

- ↑ Cited in Bruno Leipold, p 195.

- ↑ Karl Marx and Frederick Engels, Marx Engels Collected Works, volume 3, p. 237. (London: Lawrence & Wishart, 1975–2005), henceforth MECW).

- ↑ MECW, volume , p. 237.

- ↑ Karl Marx and Frederick Engels, Marx Engels Collected Works, volume 9, p. 203. (London: Lawrence & Wishart, 1975–2005.)

- ↑ Capital, Ch. 25, Section 1

- ↑ http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1863/theories-surplus-value/ch07.htm |title=Chapter 7 |work=Theories of Surplus Value |author=Frederick Engels |year=1847 |publisher=Marxists.org

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑ Fogel & Engerman, Without Consent or Contract, New York: Norton, 1989, p. 391.

- ↑ The Height of American Slaves: New Evidence of Slave Nutrition and Health

- ↑ Debating Slavery: Economy and Society in the Antebellum American South, p. 44

- ↑ Foner, Eric. 1998. The Story of American Freedom. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 66

- ↑

- ↑ Foner, Eric 1998. p. 66

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 p.181-184 Democracy's Discontent By Michael J. Sandel

- ↑ The Making of the English Working Class, (1963), p. 211.

- ↑ The Making of the English Working Class, possibly page 599.

- ↑ Competitive Advantage on the Shop Floor, p. 37.

- ↑ Helga Hallgrimsdottir and Cecilia Benoit, 2007. "From Wage Slaves to Wage Workers: Cultural Opportunity Structures and the Evolution of the Wage Demands of Knights of Labor and the American Federation of Labor, 1880-1900", Social Forces, Vol. 85, Number 3, pp. 1393-1411. http://muse.jhu.edu/login?uri=/journals/social_forces/v085/85.3hallgrimsdottir.html

- ↑ Emma Goldman: A documentary History of the American Years

- ↑ Rogue States By Noam Chomsky

- ↑ Profit Over People by Noam Chomsky

- ↑

- ↑ Interview at [http://www.chomsky.info/interviews/19760725.htm Chomsky.info

- ↑ "The highest position slaves ever attained was that of slave minister… A few slaves even rose to be monarchs, such as the slaves who became sultans and founded dynasties in Islām. At a level lower than that of slave ministers were other slaves, such as those in the Roman Empire, the Central Asian Samanid domains, Ch’ing China, and elsewhere, who worked in government offices and administered provinces. … The stereotype that slaves were careless and could only be trusted to do the crudest forms of manual labor was disproved countless times in societies that had different expectations and proper incentives."The sociology of slavery: Slave occupations Encyclopaedia Britannica

- ↑ Fragments of an Anarchist Anthropology p. 37

- ↑ Kuttner, Everything for Sale., pp. 153-4

- ↑ Quotation in by Jose Peirats, The CNT in the Spanish Revolution, vol. 2, p. 76

- ↑ To Have Or to Be? by Erich Fromm

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedamazon.com - ↑ Gramsci, A. (1992) Prison Notebooks. New York : Columbia University Press, pp.233-38

- ↑ Young, Gary. 1978. Justice and Capitalist Production. Canadian Journal of Philosophy 8, no. 3, p. 448

- ↑ Nino, Carlos Santiago. 1992. Rights. NYU Press. p.343

- ↑ Ludwig von Mises, 1996 [1949]. Human Action: A Treatise on Economics (4th ed.). San Francisco: Fox & Wilkes. ISBN 978-0-930073-18-3, pp. 194–99. (interpersonal exchange accessed at March 11, 2008)

External links

- André Gorz, Critique of Economic Reason and the Wage Slavery,1989

- Creating Livable Alternatives to Wage Slavery

- Essay on Societal Slavery

- How The Miners Were Robbed 1907 anti-capitalist pamphlet by John Wheatley.

- Land and Liberty

- Photo-story on modern-day slavery in Brazil by photographer Eduardo Martino

- Special situations in the USA

- Wage Labour and Capital

- Working for Wages, Martin Glaberman and Seymour Faber

- Slavery and the Welfare State by Stephen Pimpare, from A People's History of Poverty in America