"We Shall Overcome".... The History of the Struggle for Civil Rights in Northern Ireland 1968-1978 (Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association)

"We Shall Overcome".... The History of the Struggle for Civil Rights in Northern Ireland 1968-1978 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Author | Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association |

| First published | 1978 |

Foreward

When the Executive Committee of NICRA were discussing how to mark 10 years of the Association, we decided to commission a short history of the Association since its foundation. We did this because every Tom, Dick & Harry at home and abroad has written about, written off and written down the Association, or else blames it for its alleged key role in creating the situation with which we are faced today.

It was easy to authorise a history, but harder however, to obtain one. We are too near to the events, too entangled in them emotionally to write a glib little history that will be all things to all men. It is impossible to give an "official" NICRA view on our history, because no one person knows all the events as yet and no two people agree exactly on how those events should be interpreted.

What were we to do? Forget the idea? bury the book? spend 2 years trying to get an approved draft? We decided the style in this draft was readable some thought even too readable as the events were described very sharply. At least some of the controversies were described. The interpretation put on events and the leaving out of important aspects of the struggle, will no doubt infuriate readers. What this Association wants is for that fury to spur the makers of NICRA history and Northern Ireland history, to sit down and write out their memories, and their interpretations. No doubt the present Executive Committee could be made uncomfortable on some more recent disputes, and reasons why people left the Association.

We thank our author for making a very creditable start on the mammoth task he has begun in the assembling of the facts of the case. It will no doubt be a very long time before the differences in interpretation are settled.

The history of NICRA will be an ongoing process. After all we still do not have civil rights in Northern Ireland and history is still being made. We also want to add to our knowledge of the period covered so please send us relevant material, pictures, leaflets.

There are many items which could have a chapter of their own in the future such as NICRA 's work in the International Legal Field; How International Interest and support helped the Civil Rights Struggle; The Role of the USA - Helpful and Harmful; The Role of the Trade Union Movement in the civil rights struggle; How Non Violence as a Tactic worked - and many, many more.

We hope you find this publication interesting and stimulating, so that the democratic movement can recognise its past mistakes, and arm itself for victory in the future.

Introduction

This is not a chronology of events. It is a story, a true story, of the struggle for democracy in Northern Ireland, and the political context in which is took place. Like all stories it has its share of characters and events, but this story is more important than most, because its characters and events have shaped the course of modern Irish history. It is a story of how a political dictatorship was toppled by a simple demand for democracy and how a new totalitarianism arose in its place on the strength of political violence. It is a long story, related briefly here to include only the most important points, but it is a story calling out for a more comprehensive telling in the present confused state of Northern politics.

Only the British Government lives happily ever after in this story, but it is a story which has not yet ended. In this pamphlet it concludes with what might have been or what might yet be, but the complete story will remain unfinished until full human and civil rights have been established in Northern Ireland.

Political Scenario

The concept of civil rights in Northern Ireland is as old as the state itself. The permanently guaranteed parliamentary majority of the Unionist Party built the state on a foundation of sectarian discrimination, biased administration and a barrage of totalitarian legislation which both protected Unionism and instilled a deep sense of social injustice in the non-Unionist population. The desire for social justice, however, did not manifest itself as a campaign for civil rights until more than 45 years after the state was founded. What had happened was that Unionism had become synonymous with the denial of civil rights and the non-Unionist political organisations fought for the removal of Unionism - by the abolition of the state - and ignored the civil rights question. The dual objective of civil rights and the abolition of the state remained as a single political aim in which the national question took priority.

Led politically by the Nationalist Party and in violence by the IRA, sections of the 'Catholic' minority believed that their rights as individuals could be guaranteed only in an all-Ireland republic. Their political aspirations were articulated with equal ineffectiveness by both protagonists. The IRA carried on campaigns of violence in every decade up to and including the sixties. Each campaign was less effective than the previous one. With the prospect of victory constantly receding, the struggle became an end in itself, a form of sporadic ritual carried over from a period in political history which only Unionist discrimination made relevant. In Stormont the Nationalist Party, the largest parliamentary opposition group, bluntly refused to accept the title of Her Majesty's Official Opposition. They were opposed to the Government, but not officially, and in a consciously unofficial manner they complained about discrimination against Catholics and simultaneously practiced discrimination against Protestants in some Nationalist-controlled councils.

For electoral purposes the Republicans usually contested Westminster elections, always on an abstentionist ticket. The Nationalists settled for attendance at both Stormont and at Westminster.

The Government's answer to the problem was simple. The Republicans were interned and the Nationalists were ignored. Armed with the all-embracing Special Powers Act, once the envy of the South African Government, the Unionist Party was able to maintain the peace by interning whoever displeased it, and armed with an unbeatable parliamentary majority, it exercised its political power and patronage, content in the knowledge that Unionism would last forever. Financed by successive Westminster governments, Stormont was given a free hand to run Northern Ireland as it pleased, provided peace was maintained and loyalty proclaimed. The situation did not alter in any way until the 1960s, the era of the ecumenical movement, when the Beatles came to Belfast, men went into space and Lord Brookeborough went into retirement. It was a period of change.

Attitudes Changed

There was a change in the attitude of the 'Catholic' minority towards the state. The first generation to benefit from the 1949 Education Act had graduated from university, and the newly educated 'Catholic' working class articulated the grievances which had previously been expressed by abstentionism and non-co-operation. Having obtained the right to free education, they were now to use that education to demand other rights. The changing 'Catholic' attitude can also be traced to the influence of the ecumenical movement. The change in religious attitudes was transformed in the politico-religious atmosphere of Northern Ireland into a change in political outlooks.

The message was enlightenment, not entrenchment. Like a Messiah into their midst came a new Prime Minister, Terence O'Neill, who preached the same gospel of peace and reconciliation. It was a language which the Catholic Church was speaking at the same time.

O'Neill's Two Faces

O'Neill preached liberalism and practiced sectarianism. He drank tea with nuns in convent parlours and smiled at Catholic children as they marched past him in para-military ranks in what he called civic weeks. He had a programme to enlist the people, he said, and to the sound of reverend mothers drilling their pupils in convent school yards - Northern Ireland seemed set to march into a new era. Civic weeks began in Unionist towns and gradually worked their way outwards towards the Nationalist periphery in the west and south of the province. The Catholic attitude was one of co-operation. The Catholic Church was in an ecumenical mood and apart from the protest of a lone Republican hunger striker on the steps of Newry Town Hall, O'Neillism paraded the streets of Northern Ireland unchallenged.

When the challenge did come it was from the Unionist side. O'Neillism and ecumenism were particularly Catholic phenomena. Many of the Protestant working class had neither heard of nor experienced the ecumenical movement, and they watched the civic weeks and cross-border visits with a mixture of fear and uncertainty. Things were beginning to change in a society which had experienced no change in forty five years and when Ian Paisley preached reaction in a period of evolution, he had a ready audience. His influence however, was limited. Glengall Street Unionism was still in control. Despite his liberalism, O'Neill still retained the Special Powers Act. In local government, discrimination and gerrymandering thrived on accumulative experience. The RUC and the 'B' Specials, nurtured on a diet of IRA threats -usually imaginary - acted as paramilitary guards for the Unionist system. Unionism, despite its new image would still last for ever. O'Neill was able to withstand any challenge which Paisley had to offer.

But there was pressure on O'Neill from a different quarter. In 1964 the Wilson Report on the economic future of Northern Ireland had given the go-ahead for the build up of multi-national companies on a large scale in the province and although multi-nationalism was indifferent to civil rights, it would operate best in a politically stable system which was on friendly terms with its neighbouring states.

O'Neill's Government was hardly on friendly terms with that of Sean Lemass, himself a great exponent of attracting foreign capital, and the stage hostility between the two did not fit the British Government's economic plans for the future of the island.

Improved relations between the two governments was needed by Whitehall as much as O'Neill and Lemass needed them and accordingly the two leaders met, first in Belfast and later in Dublin. The economic significance of the meetings were clouded by the political implications and while Paisley grabbed the publicity, the three Governments grabbed the opportunity to fashion the economic future of Ireland in accordance with their aims. Political division in Ireland was to be replaced by economic multi-national unionism. It was O'Neill's job to create the right image for Northern Ireland.

More Fashionable Sectarianism

He seemed to successfully bring Northern Ireland from the crude sectarianism of the Brookeborough era into the more fashionable sectarianism of the sixties. But his success was nothing more than a media illusion because what O'Neill had achieved was a partial change in attitudes to a 50 year old problem, but he had made no effort to tackle that problem. There was no attempt to change the local government voting system so that one man had one vote and no more than one. He made no reference to the arbitrary powers of arrest and internment under which citizens of the state could be arrested and detained indefinitely without charge or trial. He failed to tackle the serious problem of the unacceptability of the forces of law and order. In short he changed the facade of life in Northern Ireland and left the reality untouched. His true politics emerged when he was asked to implement basic legislative reforms which would have protected the civil rights of the people to whom he waved at his civic weeks. He hung back.

O'Neill failed the first test of liberalism when he neglected the opportunity to implement basic democratic reforms in Northern Ireland. When the civil rights campaign presented him publicly with a set of demands for reform he turned them down. It has been suggested that O'Neill was a prisoner of his own right wing and that the granting of civil rights demands would have forced him out of office, but he came to power in 1963 and the first civil rights demands were not made on a large scale until 1968. His five years in the convent parlour was no substitute for democratic reform.

And if O'Neill was a prisoner, he was a prisoner of his own unwillingness to implement legislative reforms which would have threatened his position as Unionist Prime Minister, a position of effective dictatorship.

Original, Inventive & Novel

But if the origins of the O'Neill era are well known, the origins of the civil rights campaign are not. The campaign began with the formation of the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association [NICRA] but like many great mass movements in history, NICRA did not begin at a precise time in a definite place.

NICRA evolved from a diverse set of political aims and ideals which slowly came together to forge a unity based on a common frustration with Unionism, a broad rejection of crude Nationalism and a growing awareness of the need for an effective vehicle for political and legislative reform. It was essentially a product of the sixties. Original, inventive and novel in a stagnant political system, NICRA avalanched its way through Northern Ireland politics sweeping aside abstentionism and non-co-operation and using direct political demands to hammer on the door of Unionism. The story begins in 1962…..

Origins

In 1962 the IRA decided to hang up its guns. A five year guerilla campaign of violence had produced a handful of dead bodies on both sides, a marked increase in the number of people in prison and a strengthening of the Unionist political system. It was a campaign which had been fought and lost on the bleak hillsides of South Armagh and South Derry far away geographically from the city of Belfast and far removed from the mainstream of Northern politics.

But para-military failure laid the basis for political success inside the Republican Movement, and in the light of changing political attitudes and events in Ireland, the Republican approach to Northern politics became political for the first time in forty years. The same year the Connolly Association in London published its pamphlet "Our Plan to End Partition" in which it was pointed out that "the greatest obstacle to turning out the Brookeborough Government is the way it has barricaded itself at Stormont behind a mountain of anti-democratic legislation."

Campaign for Democracy in Ulster

In pursuit of their aims the Connolly Association sought pledges of candidates in the 1964 general election that they would press for democratic reform in Northern Ireland. A follow-up conference on the issue in 1965 eventually led to the Campaign for Democracy in Ulster, a loose alliance of Labour MPs spearheaded by Fenner Brockway and Paul Rose. Meanwhile back in Ireland the Wolfe Tone Societies, a group of Associations formed to commemorate the bi-centenary of Theobald Wolfe Tone in 1963, had decided to stay in existence to attempt to influence cultural and political trends in the country. The strongest groups were in Belfast and Dublin and they too became concerned with the weakening of the Unionist monolith at Stormont through democratic action.

Action of a sort had already begun in the form of the Campaign for Social Justice, an organisation based mainly in Dungannon and headed by Dr. Conn McCluskey and his wife Patricia. They spent a considerable amount of time documenting and quantifying examples of discrimination, gerrymandering, unfair housing allocation and administrative malpractice by Government departments, and it was perhaps this groundwork which spread the first awareness of the seriousness of the problem in Northern Ireland to the Campaign for Democracy in Ulster. The Communist Party [N. Ireland] were also active on the issue. In their 1962 programme "Ireland's Path to Socialism", they emphasised that the demand for democratic rights was one of the immediate political demands.

Trade Union Involvement

The final strand in what was to be woven ir the civil rights campaign was the Trade Union Movement, particularly the Belfast & District Trades Union Council.

The Northern Committee of the Irish Congress of Trades Union, on two separate occasions, along with the Northern Ireland Labour Party, went on deputations to see Captain O'Neill. Their demands for One Man One Vote and repeal of the Special Powers Act were ignored, and 4 Belfast-based Stormont seats were not sufficient leverage for the NILP, then a political force, to obtain movement on the civil rights front.

In May 1965 the Trades Council organised a conference on civil liberties in the lecture room o the Amalgamated Transport & General Workers Union headquarters in Belfast and several trade union leaders spoke of their concern over the failure of the Government to implement basic democratic guarantees in Northern Ireland.

The trade unionists, mainly Protestants, had a ready audience in the members of the Campaign for Social Justice, the Communist Party, the Republicans and the Northern Ireland Labour Party, all of which sent representatives. For sectarian discrimination to be condemned by the union representatives of Belfast's Protestant working class was a big step, even in the enlightened sixties. Slowly the diverse strands of political thought were coming together. The need for reform had been documented and publicised, but it was a problem which needed more than recognition - it needed action.

First Moves

The first move in what was eventually to emerge as NICRA came from the Wolfe Tone Society. The Society recognised the growing awareness of the need for a broad organisation to channel the demands for democratic reform and to this end they organised a meeting of all Wolfe Tone Societies in Maghera in August, 1966.

The outcome was a decision to hold a public meeting to highlight the issue of civil rights in Northern Ireland. This was held in the War Memorial Building in Belfast in November, 1966, and its attendance was drawn from all sectors of libertarianism in Northern Ireland, the Chairman being John D. Stewart.

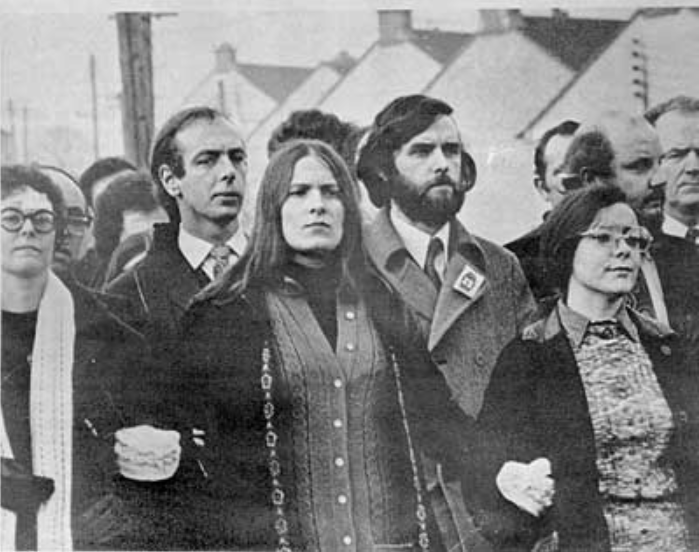

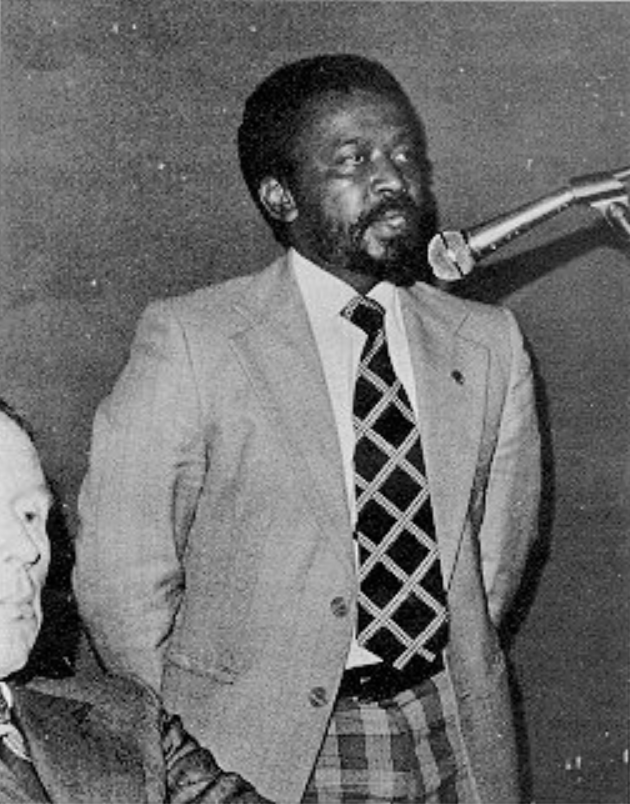

The two main speakers were Ciaran Mac An Ali, who spoke on "Civil Liberty - Ireland Today" and Kadar Asmal, who spoke on "Human Rights, International Perspective".

The support for this public meeting prompted the Belfast Wolfe Tone Society - effectively Fred Heatley and Jack Bennett - to hold another broad meeting with a view to setting up a formal organisation which could be devoted to unifying the struggle for civil rights.

Even Unionists Attended

The meeting was held at Belfast's International Hotel on January 29, 1967. All political parties in Northern Ireland were represented. Unionist Senator Nelson Elder attended, but after losing an argument for the retention of hanging for the murder of policemen, he walked out. A letter from the Unionist Chief Whip, James Chichester-Clarke, stated that he would try to get someone along. In all there was over one hundred people present and a 13 man committee was elected to draw up a draft constitution and a programme of campaign for submission to a later meeting. The 13 man steering committee later elected the following officers:

| Chairman: | Noel Harris [DATA] |

| Vice Chairman: | Conn McCluskey [CSJ] |

| Secretary: | Derek O'Brien Peters [Communist Party] |

| Treasurer: | Fred Heatley [Wolfe Tone Society] |

| P.R.O.: | Jack Bennett [Wolfe Tone Society] |

Other members of the committee were:

| Betty Sinclair | [Belfast Trades Council] |

| Billy McMillen | [Republican Clubs] |

| John Quinn | [Liberal Party] |

| Michael Dolley | [National Democratic Party] |

| Joe Sherry | [Republican Labour Party] |

| Jim Andrews | [Ardoyne Tenants Association] |

| Paddy Devlin | [Northern Ireland Labour Party] |

| Tony McGettigan | [no affiliation] |

Members did not represent their party political views on the committee and the political affiliation of each member is included in an attempt to illustrate the broad nature of the organisation. That the committee was equally conscious of their broad base was evidenced by its unanimous agreement a few days later to co-opt Robin Cole, former Chairman of the Young Unionists at Queen's University on to the committee.

A five point outline of broad objectives was issued to the press after the inaugural meeting. These were:

To defend the basic freedoms of all citizens

To protect the rights of the individual To highlight all possible abuses of power To demand guarantees for freedom of speech, assembly and association

To inform the public of their lawful rights.

These five demands later became the rallying cry for thousands of marchers. They were the inscriptions on banners in countless marches and the slogans on the lips of countless marchers. They were the demands which motivated thousands of marching feet and they were ultimately the five basic demands for which many people lost their lives. They were five demands which were not based on an elaborate political philosophy but came rather from the politics of instinct, trained and developed by fifty years of Unionist Government.

It is to these five demands that the present political situation in Northern Ireland can be traced.

First Salvo is Fired

The political situation in which the demands were made and in which the fledgling civil rights body emerged was typical of O'Neill's mirage-type liberalism. The first resolution ever passed by the new committee was a condemnation of the denial of freedom of speech exercised by Ian Paisley over the Bishop of Rippon, Dr. John Moorman. Paisley, in his unique politico-religious style, was challenging both the results of the ecumenical movement and the outcome of the O'Neill political atmosphere. Before the civil rights committee could hold a meeting to ratify the new constitution the Unionist Government, with O'Neill as Prime Minister fired the first salvo in the battle over democratic rights. On March 7th 1967, the Minister of Home Affairs, William Craig, announced a ban on the North's forty-odd Republican Clubs. It was a straight case of political censorship in which a political organisation hostile to the Government was to be banned.

While awaiting formal ratification of its constitution, NICRA offered its voice in protest against the Government decision, but a new era had already dawned in Irish politics, because for the first time under the Unionist Government the Republicans did not fade away to form fours in dark corners of fields. They stood and fought the issue on the basis of their civil right to exist as a political organisation. Within a week of the ban's introduction a Republican Club had been formed in Northern Ireland's bastion of academic complacency, Queen's University. There, for the first time in the history of the state, university students took a stand against the totalitarian Unionist Government. The chickens hatched under the free education Act of 1949 had come home to roost with a vengeance.

NICRA's Official Birth

While the Queen's students highlighted the need for the right to freedom of political association, NICRA held its meeting to ratify the constitution on April 9th 1967. It was on this date that NICRA officially came into existence. There were some changes in the executive council with Ken Banks [DATA], Kevin Agnew [Republican] and Terence A. O'Brien [Derry, no affiliation] replacing Andrews, McMillen and McGettigan.

With the exception of the Nationalist Party, all political parties and the Trade Union movement were represented in the struggle for civil rights. The Nationalist absence was not through any conscious political decision but stemmed rather from a failure to recognise changing political conditions, a failure which ultimately led to the party's melting away in the spring of the civil rights campaign.

Product of Frustration

The formation of NICRA marks the formal beginning of the civil rights campaign. Although the concept of civil rights was inherent in a political system with an in-built one party majority, the reality of the struggle came only after several other avenues of politics and violence had been explored without success, so that when NICRA finally emerged it was as much a product of frustration with Unionism as a demand for political change.

After 47 years of effective dictatorship, the question of civil rights was tackled seriously for the first time in 1967. It was the beginning of the end for the Unionist Party and the beginning of a new era for Northern Ireland.

Early Days

For the first 18 months of its existence NICRA was nothing more than a pressure group. Its main activity was writing letters to the Government, mainly to Bill Craig as Minister of Home Affairs, complaining about harassment of political and social dissidents ranging from Republicans to itinerants. But it rarely went beyond the stage of dignified written protest. The Government's reply - when it came - was usually one of denying that a particular abuse had occurred and suggesting that even if the NICRA allegation was true, there was probably a very good reason for the abuse.

It was a time of frustration for NICRA. O'Neill, by polishing civic weeks to a fine art, had pushed discrimination to a high degree of sophistication.

First A.G.M

NICRA's most important advance in the period was to hold its first annual general meeting in February 1968, which produced a few new faces, but little in the way of a concerted civil rights campaign. The new faces were John McAnerney [Campaign for Social Justice], Frank Campbell [Republican], Peter Morris [no affiliation], Jim Quinn [no affiliation], Frank Gogarty [Wolfe Tone Society], and Rebecca McGlade [Republican]. They replaced Bennett, Harris, Banks, O'Brien, Dolley and Devlin. Robin Cole [Unionist] was re-elected with the highest number of votes but he later resigned from the executive. Betty Sinclair became the new chairman. But a change of executive brought little initial change to a political situation in which the Government carried on with its "not an inch" policy.

The situation would have probably continued to the present day had the decision to take the struggle to the streets not been made. Street violence was nothing new in Northern Ireland, but street politics were. Marching was something which both Orange and Republican organisations indulged in. Government Ministers often took part in the former and usually banned the latter.

In April 1968, for example, the Annual Republican Easter Parade in Armagh was banned, the excuse being that a Paisley prayer meeting was planned for the same day along the route.

Marches were therefore a physical manifestation of Northern Ireland politics and the recognised territorial divisions of the two sectarian groups meant that marching had become a form of sectarian one-up-man-ship. That NICRA should take to the streets was a proposal to consider seriously.

It was the Government's ban on marches which forced NICRA into holding street demonstrations. After the ban on the Easter Parade in Armagh NICRA attended a Republican organised Rally Saturday after Easter [April 20] to protest against the ban on parades and a week later there was another meeting at the same spot to protest against the ban on Republican Clubs. Speakers at this meeting included Rev. Albert McElroy, leader of the Liberal Party, Eddie McAteer, leader of the Nationalist Party, and Austin Currie MP. NICRA was slowly coming to realise that a ban on street demonstrations was an effective Government weapon against political protest, and that although letter writing to Stormont was a fine form of occupational therapy, it was unlikely to bring any worthwhile results.

The Caledon Squat

Direct action in politics had begun. In June, members of the Brantry Republican Club and Austin Currie squatted in a house in Caledon, Co. Tyrone, which they believed had been unfairly allocated. Since there was no impartial administrative mechanism by which house allocation could be made, and since there was no method of appeal against administrative malpractice, the only course open to those wishing to object to a Government policy was direct action. In July members of the Derry Housing Action Committee continued the campaign for impartial house allocation by blocking Craigavon Bridge and 17 of them were arrested. The time for NICRA's direct action had come.

The first civil rights march took place from Coalisland to Dungannon on Saturday August 14, 1968. It was organised to protest against housing allocation in the area and it was supported by more than 2,000 people. NICRA's march was faced with over 1,000 supporters of an organisation known as the Protestant Volunteers, a group politically inspired by Ian Paisley and para-militarily groomed by Major Ronald Bunting.

The police protected the civil rights marchers with minimum cover and denied them access to the town square. A few of the marchers were injured. Gerry Fitt and Austin Currie were present and Fitt later made a special report to the Prime Minister, Harold Wilson, in which he complained about the role of the police. The marchers sang "We shall Overcome" before they broke up.

As a march the Coalisland to Dungannon journey was nothing more than another one in Northern Ireland's lengthy list of marches, but as a political event this march can be firmly marked as an historical occasion which was to shape the future political development of Northern Ireland. On the day it achieved little, but in retrospect it was the signal for the beginning of the biggest mass movement seen in Ireland this century. On Monday September 2nd NICRA announced that a march would be held in Derry at some time in the future to protest about the housing situation in the city, unemployment, local government reform and the right of free speech and assembly. The march was eventually planned for October 5th, and it came as no surprise to anyone when the Apprentice Boys of Derry gave notice of a ceremony which they intended to hold on the same day along the same route. Bill Craig banned both and NICRA decided to go ahead.

First Blood is Shed

October 5 in Derry witnessed the first bloodshed in the present violence in Northern Ireland. The blood was that of many of the 2,000 marchers who defied Craig's ban. It was spilled by RUC batons and among those injured was Gerry Fitt. Three other Westminster MPs, Russel Kerr, Ann Kerr and John Ryan witnessed the events. They saw the police baton the leading marchers in Duke Street and they saw that as the marchers turned to go back down the street they were ambushed by another company of police. Although only 2,000 people were present, the film of the brutality taken by an RTE cameraman flashed around the living rooms of Northern Ireland and the political upheaval feared by Unionists for fifty years had begun.

Prior to the Derry march the civil rights campaign had attracted the support only of the politically conscious. It was not a mass movement in the sense that it attracted massive support. Its non-violent methods and its refusal to equate civil rights with Irish nationalism made it virtually an unknown quantity in politics. But Bill Craig's police force stamped the authenticity of NICRA as a broad movement on the heads of the people in Duke Street and on the hearts of the television public. The Government's political justification for the Duke Street police ambush was that NICRA was a subversive organisation intent on destroying the state.

It was the traditional Unionist response to any attempt at democratic progress but with NICRA's demands sticking rigidly to a policy of political reform and ignoring completely the issue of the state's existence, the Stormont Government had made its first wrong move in retaining power in nearly 50 years. Nothing would ever be the same again. Almost 90 people were treated in hospital for injuries sustained at the hands of the police and the first minor riots in Derry began over the week-end. In the political field events moved fast.

NICRA Begins to Grow

In Derry a Citizens Action Committee was formed with Ivan Cooper as chairman and John Hume as vice-chairman. Although the nucleus of the Derry Committee had been involved in the planning of the Derry march, much of the support for the new organisation was based on a reaction to the police violence. Elsewhere in the province local civil rights groups sprang up in solidarity with NICRA and although they gave the NICRA executive some headaches through the holding of unauthorised street activities, they were a welcome illustration of the upsurge in popular support. In Queen's Univerity the Derry violence had coincided with the relaxed atmosphere at the beginning of the first term and, shocked by what they had seen on television, many of the students joined in a spontaneous march from the University to the City Hall in protest against police brutality in Derry. The march ended with a sit-down in Linenhall Street at the back of the City Hall and the afternoon 's events gave rise to an informal organisation in the University. It was called the People's Democracy (PD).

Although essentially a product of the civil rights campaign, the PD was made up of politically naive students who eventually found leadership in the politically aware personalities of Michael Farrell, Kevin Boyle, Cyril Toman and Bernadette Devlin.

Although PD grew out of a genuine desire for civil rights by a broad section of the student population, its leadership aimed it in the general direction of a socialist political philosophy and away from what they regarded as reformism. In the whale's belly that was Queen's, cut off from the outside world, the students were easily led from reform to revolution in a matter of weeks and PD declined into a narrow, politically sectarian organisation united only by the politics of impatience. Initiated into politics by the need for civil rights they decided that only socialism could provide such rights and immediately demanded socialism. Like the Nationalist Party they confused the demand for civil rights in the existing state with a demand for a specific form of government which only the abolition of the state could provide.

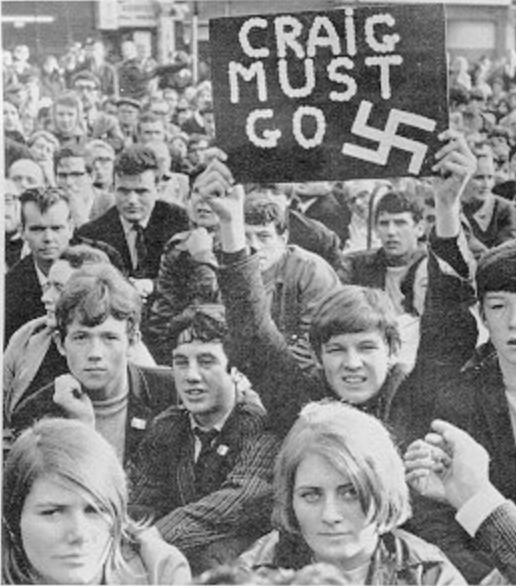

But in the political atmosphere in the autumn of 1968 the umbrella demand was civil rights. Several groups sprang up throughout the country and the support for NICRA's campaign was expressed at another march in Derry on November 16. The RUC's use of batons against the 2,000 in October produced a massive turn-out of 20,000 in November, especially in view of Craig's banning the march. A new demand was now chanted at civil rights marches: "Craig Out".

Unionists in Retreat

The Unionist Government was in retreat. O'Neill was in trouble on several fronts. Inside the Cabinet there was opposition to Craig's heavy handed tactics in dealing with the first Derry march, an opposition not based on humanitarian grounds, but founded rather on the adverse publicity which the incidents received. O'Neill was also in trouble with the extreme right wing of his own party in Stormont, which was expressed on the streets in the form of Paisley and his mobs. Relations between the Catholic community and O'Neill were also in decline and the RUC had destroyed in ten minutes what years of civic weeks had built up. But the most important front on which O'Neill was in difficulties was in his relations with Westminster. The Campaign for Democracy in Ulster had prepared the groundwork for concern about civil rights in Northern Ireland and the cut on Gerry Fitt's head brought the issue into the House of Commons. Westminster was concerned that peace was not being maintained and on November 4, Prime Minister Harold Wilson summoned O'Neill to London.

With O'Neill went Craig and Faulkner - Craig because he was the Minister for Home Affairs, Faulkner because he was the brightest boy in O'Neill's Stormont class. As Wilson later said in the Commons he thought that political reform in Northern Ireland had been "a bit too moderate so far", but in a five point plan of reform sent to O'Neill on November 21, Wilson proved that he too was moderate on the issue. The "reforms" included the abolition of the company vote in local government elections, the appointment of an Ombudsman at some future date, re-organisation of local government by 1971, a recommendation -nothing stronger - to local authorities to reform their housing allocation procedures and the establishment of a commission to run Derry in place of the Corporation. It was an empty gesture by Wilson. Derry had gone from "One Man, One Vote" to "One Man, No Vote" with the abolition of the Corporation, the Ombudsman might never come and although the company vote had been abolished, the property qualification had not. One man could still have more than one vote. Wilson's concern for Civil rights proved as strong as that of O'Neill.

Meanwhile back on the streets NICRA continued to march. Despite a take-over of Armagh city centre by Paisley and his followers in the early hours of November 30, a civil rights march planned for the city that day went ahead. Its route was blocked and a meeting was held at the RUC barrier. A lawful march had been halted by an illegal meeting and the RUC - the para-military arm of the Unionist Government - was either unwilling or unable to do anything about it. Things were rapidly coming to a head in politics. Craig had become isolated in the Cabinet. In December he said "When you have a Roman Catholic majority, you have a lesser standard of democracy", and O'Neill effectively decided to remove him from office. Before doing so he made his famous "Ulster at the Crossroads" speech on television on December 9. Armed with an upswing in public support he had the confidence to sack Craig two days later. There were two reactions to the speech and the sacking. The PD decided to form a number of extra-mural branches as soon as the reforms were announced and the following day, for example, they held a meeting in Dungannon to gloat at Craig's sacking. The reaction of NICRA was much different. They decided to give O'Neill one last chance and they declared a "truce" for one month without marches or demonstrations.

To Diffuse Sectarianism

The NICRA decision was arrived at after much discussion on the Executive Committee. The course of action was finally agreed upon for two reasons:

- the promised reforms must be given a chance to work, both for their own sake and for the credibility of the whole principle of civil rights demands, and

- the chances of sectarian violence were growing by the day and anything which might defuse the situation would be welcome.

The year ended peacefully. In the period from August to December the civil rights campaign had managed to split the Unionist cabinet, arouse concern at British cabinet level, bring thousands of people demanding civil rights on to the streets and produce a general public awareness of the lack of democracy and a political programme for its introduction. On the negative side it had aroused extreme Protestant reaction as a result not only of the marches but also of the Government's political reactions and it had given rise to an impatient group of students seeking instant revolution in a text book society. In the light of the influence of the organisation since its beginnings, this four month period put NICRA in the vanguard of the struggle for civil and human rights in N. Ireland. But there was still a long way to go.

1969

1969, which was to be a year of violence, began violently. Alarmed that the NICRA one month truce with O'Neill might lose the impetus of the civil rights campaign, the PD decided to take the initiative and bring their campaign back on to the streets. Since one of the few effective methods of making political demands at the time was the march, it was necessary to introduce a variety of march routes to both attract support and add newsworthiness to the demands. The PD decided on a march from Belfast to Derry through some of the most Loyalist and reactionary rural areas in the North. They left Belfast on January 1, and from their first steps outside the City Hall until their last faltering steps into Guildhall Square in Derry, they were harassed, manhandled and beaten.

Sectarian Feelings Heightened

The RUC, despite the appearance of protection, made little effort to prevent attacks on the marchers apart from advising re-routing or cancellation of the march. Attacks were made in Antrim and Toome, outside Maghera, in Dungiven, at Burntollet Bridge and on the way into Derry. As an exercise in marching it was either foolhardy or brave, but as part of an attempt to put political pressure on a Government to grant basic democratic reforms it succeeded only in raising the political temperature. The end result of the march was a heightening of sectarian feelings. The Loyalists, angered by what they regarded as a provocative march, could feel no sympathy towards the civil rights campaign, even though they too could benefit from the same civil rights. They saw civil rights as a threat to the Government, and consequently as a threat to Protestant privilege. The PD march helped to drive the Protestant working class into the arms of Paisley and Bunting.

On the Catholic side the march, particularly the Burntollet ambush, was seen as a Protestant attack on the Catholic students. Civil rights was slowly becoming identified in the Catholic mind with opposition to the Unionist regime, and that meant opposition to the state. A conscious attempt to organise a broad nonsectarian civil rights movement was being gradually identified with a sectarian ideology and the PD's failure to distinguish between political progress and political turmoil hardly helped to reassure the Loyalist population.

The situation was made worse after violence erupted at a PD march in Newry on January 11. The march had been banned from entering a part of the town and violence broke Gut at the RUC barricades when the march arrived.

The trouble began when the RUC retreated behind their tenders as a violent element in the crowd confirmed the worst fears in Unionist minds - civil rights meant Catholic rights, and Catholic rights meant violence. The barricades, the police baton charges, the marching masses all combined to give the atmosphere of revolution to the PD, which was slowly losing its broad base in the University and becoming an extreme left-wing organisation intent on using the civil rights struggle for a political end. Their instinct at the height of the Newry violence was to occupy the local post office. NICRA's efforts to nullify the PD influence by co-opting Michael Farrell and Kevin Boyle on to the executive committee failed to control the lunatic fringe.

But if there was trouble on the civil rights front, there was even greater dissention in the Unionist Party. O'Neill, having failed to placate the Catholic minority now found himself under accusation in his own party that his drinking tea with the reverend mothers had encouraged the concept of civil rights. He was having difficulty in maintaining party unity in the face of the civil rights problem, and with influence over political events slowly switching from Stormont to the streets, any solution which did not entertain the granting of immediate civil rights demands was found to fail. When O'Neill was at his weakest Faulkner resigned on January 24.

"Turned Queen's Evidence"

The resignation came as a shock to the stability of the O'Neill Government. Faulkner had been Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Commerce, but his true talent was politics. Recognising O'Neill's problems he attempted to move in on the premiership by politically turning Queen's evidence against his boss in the hope that he could obtain power as O'Neill fell. O'Neill put his political career to the test by announcing a Stormont General Election for February 24. It was an election designed to do two things:

- It was designed to strengthen O'Neill's position within the party so that he could plan his future political strategy with his most dangerous Unionist enemies relegated to the back benches, and

- It was aimed at capturing the Catholic vote which O'Neill had cultivated for years, so that he could point to his acceptance among Catholics in the face of criticism from Westminster. But the sectarian feelings had been raised too high for O'Neill to succeed.

The majority of Unionist nominations were won by Faulknerites and the majority of Catholics stuck to their sectarian politics. Even O'Neill's campaign for personal support - "I'm backing O'Neill" - failed to attract more than a section of the middle classes.

"Young Lions into Old Guards"

The election obviously involved civil rights as an issue. The PD decided to temporarily abandon revolution and seek seats in what they regarded as fascist Stormont. Michael Farrell, Eddie Weigleb, Bernadette Devlin and Fergus Woods were among the PD candidates and Woods came within a few hundred votes of capturing the Nationalist held seat in South Down.

Outside the PD several candidates stood as independents on the civil rights ticket. John Hume, Ivan Cooper and Paddy O'Hanlon stepped into Stormont on the strength of their apparent leadership of civil rights marches and at the expense of the Nationalist Party whose failure to become involved in civil rights had now finally led to political oblivion. The defeat of McAteer, Gormley and Richardson, however, did not mark a victory for political progress. The return of "civil rights" candidates was an election illusion because although Hume, Cooper and O'Hanlon fought on the issue of civil rights they were under no party discipline in Stormont and the passing of time saw the young lions of civil rights rapidly evolve into the old guard of nationalism, a process completed with the formation of the SDLP.

That the civil rights campaign was abandoned on passing through the doors of Stormont was apparent when Ivan Cooper, in his maiden speech, welcomed the establishment of the Derry Development Commission. In his maiden speech John Hume asked whether politics were going to remain on the streets or be fought out in parliament and as an infant parliamentarian he obviously favoured the latter. In doing so he effectively set himself up as a spokesman inside parliament for the thousands who had marched outside, and although he was identified as such in the popular mind , as a result of his non-stop media appearances, his non-accountability to NICRA and the mass movement set him and his colleagues on a party political as opposed to a broad political course. Like the PD before them the SDLP were to use the popular cause of civil rights to gain political support and then attempt to swing a mass movement behind them on the basis that only their political philosophy could guarantee such rights.

For O'Neill the election was a disaster. The electorate had told him what sort of Ulster it wanted in no uncertain terms. It wanted an Ulster without O'Neill and although he had an unofficial parliamentary majority of eleven, his pledge to stay in office rang hollow in the election aftermath. He lasted exactly two months. On April 28 he resigned.

In retrospect he has been hailed as a possible liberal saviour, but an interview he gave to the Belfast Telegraph two weeks after he resigned showed the true nature of his liberalism.

"It is frightfully hard to explain to Protestants that if you give Roman Catholics a good job and a good house, they will live like Protestants, because they will see neighbours with cars and television sets. If you treat a Roman Catholic with due consideration and kindness they will live like Protestants in spite of the authoritative nature of their church."

O'Neill's liberalism held good as long as he was in office. His liberalism was the liberalism of real-politik, and his politics were the politics of Unionism.

PD Gets "Pushy"

But if things were going badly for O'Neill, they were not going much better for NICRA. The problem was a combination of Hume and Cooper in parliament and Farrell and Devlin on the streets. At the AGM in February, Farrell and Kevin Boyle were elected to the NICRA executive. The PD, anxious to steer the civil rights campaign in their direction, hoped that their men on the inside would keep up the momentum of marching, in an effort to force a political crisis in the country. But the political crisis inside NICRA had to be staged first. On March 7, the "Irish News" carried a report that Bernadette Devlin, speaking at a meeting in Gulladuff, had announced details of a march from the centre of Belfast to Stormont for the end of the month, to be organised by NICRA in association with the PD. NICRA had no previous knowledge of the march and although Farrell and Boyle denied that they had been responsible for the statement they proposed that the march should go ahead, despite the fact that it would mean marching through the heart of Loyalist East Belfast.

At an executive meeting to discuss the proposed march three separate pro-PD proposals were put forward be either Farrell or Boyle and on each occasion the vote was divided exactly seven each. On each occasion also the Chairman, Frank Gogarty, used his casting vote in favour of the march. The outcome was that four members of the executive, Fred Heatley, Raymond Shearer, Betty Sinclair and John McAnerney resigned. Heatley later admitted that he had acted on impulse and McAnerney, shortly before his death in 1970, also agreed that the resignations were foolisn and unnecessary at that time.

But four valuable members of the executive had gone at a crucial period in the civil rights struggle and eight of the Omagh CRA leadership followed soon afterwar The first open split in the NICRA ranks had appeared, and although an emergency general meeting on March 23rd ended in some confusion, the majority attending were in favour of abandoning the proposed march to Stormont. That march never did take place but it proposed implementation within the organisation had caused severe damage.

In America, Australia and Britain support groups became divided and confused about what was happening in Ireland and the stormy executive committee meetings even spilled out on to the public demonstrations, where, on at least one occasion, speakers criticised each other from the same platform. NICRA's problem was that it was a mass movement which had sprung into activity almost overnight following the Derry march on October 5. Many new recruits to the organisation were unaware of the political role of the movement as an agitation body for civil rights and nothing else, and the PD was able to cash in on the frustrations of NICRA's impatient element.

Loyalist Bombs Explode

There was an impatient element also within the Unionist population. Annoyed at O'Neill's failure to tackle the civil rights problem in a military manner, militant Loyalists blasted him out of office by damaging water and electricity supplies on 20th April 1969. At the same time his Minister for Agriculture, James Chichester-Clarke, resigned on the grounds that the introduction of one man, one vote "might encourage militant Protestants even to bloodshed". O'Neill, trapped by Westminster on the one man, one vote issue, was hounded out of office as the fall guy for the failure of the Unionist Party to recognise the changing political situation. But the new premier was nothing more than a new face on an old policy, and worse still, it was a face without a political brain to back it.

Samuel Devenney's Death

It was during Chichester Clarke's term of office that the first murder occurred. On Saturday, April 19th, civil rights supporters held a sit-down demonstration in Derry which was attacked by a Paisley-led counter demonstration. In the violence which followed the RUC took the side of the loyalists and severe rioting occurred throughout the city. The RUC led a number of raids into the Bogside, injuring a total of 79 civilians. During one raid they broke down the door of 42-year-old Samuel Devenney's house and in front of his children beat him senseless despite pleas for mercy from his daughter.

When the baton blows had stopped Devenney was a crumpled heap on his living room floor, an innocent victim of police violence. Three months later he died in hospital in Belfast where he had been since his beating. An inquest the following December stated that he had died of natural causes. To the minority it was one of the most natural causes in the world. A year after the attack Sir Arthur Young, then head of the RUC, announced that Scotland Yard detectives were being brought in to take over an inquiry into allegations of police brutality in the Devenney case.

In November, 1970, Young finally admitted that the inquiry had failed because of lack of evidence and he referred to "a conspiracy of silence" among members of the RUC. Home Secretary, Reginald Maudling, announced the following day that the entire matter was the responsibility of the Northern Ireland Government. Devenney's blood had been spilled under a Labour administration and now his murder was being concealed by the Conservatives.

The blood which flowed from Sam Devenney's head to his living room floor was the first blood to be spilled in a case of murder in the events directly connected to the civil rights demands. It was the Unionists' reply to a demand for the reform of a bigoted administration, a resort to physical violence in the last analysis.

On June 1 NICRA announced a return to the streets having given the Government sufficient time to announce a timetable for major civil rights reforms. Their demands to the Government were:

one man, one vote in local government elections;

votes at 18 in both local government and parliamentary franchise;

an independent Boundary Commission to draw up fair electoral boundaries;

a compulsory points system for housing;

administrative machinery to remedy local government grievances;

legislation which would outlaw discrimination, especially in employment;

the abolition of the Special Powers Act and the disbandment of the 'B' Specials.

As Chairman, Frank Gogarty pointed out the following week, NICRA did not expect instant legislation, but they were demanding a calendar showing when the Government's reforms would be carried out. Chichester-Clarke's honeymoon period was over and the change of leadership had managed to give only a brief respite from the year's rapidly changing political situation.

Dog-Fights of Irish Politics

The Unionist Government continued to prove either incapable or unwilling to act on the civil rights demands. Westminster hoped that everything would settle down peacefully again, hut the problem remained. On June 28 the first of the "post-truce" civil rights marches took place in Strabane. The success of NICRA up to then was illustrated by the assortment of speakers who were willing to give of their services: Eamonn McCann, Bernadette Devlin, Austin Currie and Conor Cruise O'Brien. McCann attacked Currie, Currie attacked McCann, Devlin attacked Currie and O'Brien attacked the Unionists. The political dog-fights of Irish politics were being fought out on a platform provided by NICRA. Bernadette Devlin's main point was that it was time they [presumably the PD] looked around to see not who they were marching against, but who they were marching with, and her attitude was indicative of the political sectarianism which had entered the civil rights campaign. Civil Rights had become party political prerogatives and several groups were unwilling to play the game unless they owned the ball.

The following week, July 5, NICRA held another march and rally in Newry. It passed over the intended route of the January march without trouble, but the real tension on this occasion was the PD - CRA relat ionship. After the march the PD held a meeting to discuss the matter and Cyril Toman spoke of the great gap between the two organisations. On July 21 most of the Armagh NICRA committee resigned because of the tendency of the PD to use civil rights as a party political platform. Mr. Tom McIntegart said that his committee believed that they could ultimately destroy the civil rights movement.

First Deaths

As the rift between PD and NICRA grew, violence began in several parts of the province. Most of it stemmed from the July Orange marches. On July 12 there was sectarian violence at Unity Flats in Belfast. On 13th there was similar violence in Derry and in Dungiven and by July 14 the Crumlin Road - Hooker Street area of Belfast had become a permanent trouble spot. Police baton charges in Dungiven left 66 year old Francis McCloskey dead and in Belfast's Disraeli Street a Catholic house was burned. On August 2 violence broke out again in Belfast at Unity Flats and at Hooker Street and it continued at regular intervals throughout the week. NICRA's position as a mass movement on the streets became hopeless. In Dungannon on August 11, for example, 100 members of NICRA picketed a meeting of the local council in protest against its housing policy. An event which six months previously would have received little opposition from the Unionist population was met with a hostile crowd and violence eventually broke out. The RUC batoned the civil rights picket and arrested 15 of them. Civil Rights protests had become identified as being Catholic in the increasing sectarian violence and the RUC joined in vigorously on the Protestant side.

The violence which began in Derry on August 12 and spread to Belfast later in the week changed the face of Northern politics. Following the RUC attempt to invade the Bogside the NICRA executive sought a meeting with Mr. Robert Porter, Minister for Home Affairs, because, they said, the Bogside situation had been completely mishandled. They felt that trouble could escalate throughout the province and proposed that the Minister should immediately withdraw the RUC from the Bogside. If the Minister refused they would have no alternative but to defy his newly imposed ban on marches and hold protests throughout the North. The ban was defied and it was after a CRA meeting in Armagh on August 14 that the 'B' Specials from Tynan murdered John Gallagher. In Belfast the RUC ran riot and murdered a nine year old boy in Divis Flats. Other deaths followed and the first widespread violence of the present era had begun.

Internment is Introduced

The Government's response to the violence, for which it bore a heavy responsibility, was to intern 24 republicans under the Special Powers Act. Westminster's response was to send in units of the British Army. In Belfast NICRA established its own information service and organised an ambulance service through the hastily erected barricades for those who wished to leave the city. NICRA stated that the troops recently flown in from England must remain until the 'B' Specials were disbanded because only a directly controlled security force from Westminster could guarantee the Catholic minority immunity from the forces under the control of Stormont. The following day, August 18, the executive demanded the release of the 24 political prisoners then interned in Crumlin Road prison under the Special Powers Act, and the disbandment of the 'B' Specials within 48 hours. Two members of the NICRA executive were among those interned.

The violence in the North had its repercussions in the South. At the height of the riots Jack Lynch, the Fianna Fail Prime Minister, announced the movement of "Field hospitals" and support troops up to the border. His military exercises involved only the rump of the Irish Army, the operative section of which was on duty with the United Nations in Cyprus, but his move was political rather than military.

He had to be seen doing something to ensure his survival as leader of Fianna Fail in view of the threat to his position from Neil Blaney and Charlie Haughey.

To allow the Catholic population of the North to appear as victims of Protestant violence on southern television screens would have been verging on political suicide for the leader of a party which used national re-unification as an important part of its political doctrine.

Lynch also had problems with the IRA which in the previous few years had swung to the left and could pose a political threat to the electoral strength of Fianna Fail. With the beginnings of the Northern violence the prospect of a left-wing IRA rising to a position of political strength through the various defence committees became a reality and the field hospitals were a ploy to head off the IRA strength in the Six Counties.

Fianna Fail's Involvement

The IRA itself had taken little part in the August violence. Dormant since 1962 political policies had dominated its activities and the violence had caught it unprepared, but the events in Derry and Belfast brought it suddenly back again to para-military reality. Fianna Fail's aim was to either short circuit or control the IRA position in the North and to this end a special fund of £100,000 was set up by the Cabinet to provide relief to the people of the North. "Relief", as Haughey later pointed out at the Dublin Arms Trial meant the following:

"We were given instructions that we should develop the maximum possible contacts with persons inside the Six Counties and try and inform ourselves as much as possible on events, political and other developments, within the Six County area".

Civil Rights was a prime area for information and infiltration. In early September after initial discussions with Haughey the Director of Irish Army Intelligence agreed to implement a recommendation from two of his officers that a "relief" centre should be set up in Monaghan so that it could be used as a focal point for intelligence gathering on the North.

A weekly sum of £100 to finance the office was laid aside and provision was also made for the production of a weekly newspaper. Two editions of a news-sheet, "The North' appeared at the end of September, but this was replaced by the "Voice of the North" in early October. Meanwhile two other publications were also financed by the Dublin Government. They were a booklet entitled "Terror in Northern Ireland", an account of the August pogrom in Belfast, by Seamus Brady and "Eye Witness in Northern Ireland" by Aidan Corrigan. Of the two, the latter was the more sinister.

Speaking at a press conference to launch the book in Jury's Hotel in Dublin on October 5, 1969, Corrigan announced that he was chairman of Dungannon Civil Rights Association and that "a number of civil rights groups, such as those in Fermanagh and Dungannon, had only tenuous affiliations with NICRA, and an altered constitution would tighten the organisation and permit discipline and control to be maintained".

Fianna Fail's Man

What Corrigan did not reveal at the press conference was that 50 £1 affiliation fees had been paid into the NICRA headquarters earlier that month in the names of 50 people from the Dungannon area. He went on to speak of other civil rights groups including one in Monaghan which "was formed during the riots in mid-August and has since been organising meetings on the Civil Rights campaign in the south." In his opinion the constitution of NICRA was "a stumbling block" as it did not permit satisfactory representation from Civil Rights groups outside Belfast. Corrigan was Fianna Fail's man inside NICRA and he was intent on moulding the organisation in the interests of his masters. For the Unionist population their worst fears of NICRA had been confirmed.

Fianna Fail were also active in influencing other groups in the North, groups which would determine not only the future of NICRA, but the future of all of Ireland. The first of these was the broad range of defence organisations set up after the August pogrom. Any "doomsday" situation in the North would have to be faced by these groups and if Fianna Fail could retain a controlling interest in them, their future political stake in the Six Counties was guaranteed.

Captain James Kelly, an Irish Army Intelligence Officer, held a meeting for all defence groups in Bailieborough in October and a few days later £5,000 of the "relief" fund was channelled in this direction. But more important than the defence groups was the IRA which had seen the return of far more "sleepers" than there had been members.

The men who had been "out" in the forties and fifties flocked back in droves to take up where they had left off. But out of touch with the IRA's new political policies they found it difficult to integrate into the organisation and the violence in Belfast and Derry had created a political aftermath in which the finer points of socialism were rather difficult to dwell on. There was thus a ready-made cleavage between the sleepers and the activists, a cleavage which the Dublin Government was glad to exploit.

Father and Mother of the Provos

The apolitical element were willing to accept arms and money unconditionally and an undetermined amount of the £100,000 is reliably believed to have found its way into the hands of the "unofficial" IRA group in Belfast. In the early days of September 1969, the Provisional IRA was conceived in Belfast, fathered by Fianna Fail and mothered by the fear and uncertainty of the post-pogrom era. The "official" group within the IRA did not conform to the grant-aid requirements of Fianna Fail.

The three elements in the Fianna Fail grand design - the defence groups, NICRA and the IRA - were to be cemented together by "The Voice of the North", a mouthpiece for the politics of Fianna Fail. The paper began by equating civil rights in the North with Fianna Fail in the South. By its third edition it was carrying articles on Eamon de Valera's policy on the North, propounded twenty years previously. By April 1970 it was carrying an advertisement for a Provisional meeting in Armagh and by May it had articles in favour of EEC entry by Aidan Corrigan and Bishop Philbin. Civil rights was only an appetizer in the main meal of a Fianna Fail attempt at gaining a foothold in Northern politics. The defence groups soon melted away when the threat of additional Protestant pogroms became unlikely, but the Provisional IRA went from strength to strength until it eventually broke free from those who had initially financed it. NICRA remained independent and the struggle went on.

'B' Specials Are Disbanded

The aftermath of the August violence had seen more than the barricades and the emergence of defence groups. In political terms it meant confirmation of the partiality of the RUC and the naked sectarianism of the 'B' Specials. In early October the Hunt Report on the police recommended the replacement of the 'B' Specials by a new 4,000 strong force under the control of the British Army and the establishment of a police reserve force. Security was to be regarded as a military responsibility under the control of Whitehall and the RUC were to be gradually disarmed.

In terms of the civil rights struggle this was a partial victory in that it laid the basis for additional reforms in the future. A disarmed RUC would be a massive improvement from the August riots and the disbandment of the 'B' Specials was regarded as a major victory. At the time the role of the new force, later called the UDR, was not clear and the sectarian nature of this group did not emerge until later. But some progress had been achieved.

On the day previous to the Hunt announcements, the Electoral Law Bill was given its second reading at Stormont. This was a Bill designed to abolish plural voting and bring the franchise into line with that in Britain. Other reforms at this time included the appointment of a Minister for Community Relations and a Bill appointing a Commissioner for Complaints, to inquire into allegations of discrimination. Chichester Clarke promised to review the law on incitement to religious hatred and there was to be an anti-discrimination clause in government contracts. Public bodies were to make a declaration of equality of employment opportunity and to adopt a code of employment procedure. A Local Government Staff Commission was to advise councils on filling senior posts. House building and allocation had been removed from the hands of local councils and placed under the control of a new central housing authority, later called the Housing Executive.

A Period of Progress

It was a period of progress. The outstanding NICRA demands still included the repeal of the Special Powers Act and the revision of legal administration. As the year ended the re-structuring of the new Ulster Defence Regiment became added to the list of demands, but in the late autumn of 1969 NICRA had reason to feel that its campaign had not been in vain. At the end of November the executive was able to announce that they saw no immediate prospect for a return to the streets to obtain their outstanding demands in view of the Government's three month ban on marches.

The struggle was far from over, however. The legislation necessary to bring into force point six of the Downing Street Declaration of August was still a long way off:

"in all legislation and executive decisions of Government every citizen of Northern Ireland is entitled to the same equality of treatment and freedom from discrimination as obtains in the rest of the United Kingdom, irrespective of political views or religion."

On the civil rights front the PD eventually decided that they would be unable to use NICRA as a vehicle for their political views and on 23 November they took their 2nd formal step towards becoming an orthodox political party. At their first annual general meeting they decided to issue membership cards and "the people" no longer automatically qualified for membership. By February 1970 they had announced that they would not be standing for elections to the NICRA executive committee because "the problems of Northern Ireland cannot be solved by obtaining equal shares of poverty and misery.

The CRA is not a socialist organisation and by its nature cannot extend its fight from immediate injustices of Unionist rule to the stranglehold of British Imperialism which underlies them. We want to devote all our energies to the struggle against imperialism North and South of the border and the achievement of a workers and small farmers republic." That much at least had finally been cleared up. From that point onwards PD dropped the civil rights issue.

NICRA Office Established

The second major progressive step achieved in the struggle for civil rights at this period was the acquisition of an office for NICRA. This was in Belfast's Marquis Street, from where NICRA has continued to operate ever since. With the office established there was need for full time staff and they were appointed in December 1969. The job of Organiser was filled by Kevin McCorry a graduate of Trinity College Dublin. He remained in the position until 1975. His assistant was Margaret Davison who still works in the Office for NICRA. The Office and the staff were financed by American dollars which poured into NICRA after the August violence and by the "widows' mites" gathered in Northern Ireland. As the only readily identifiable anti-unionist organisation from a distance of 3,000 miles, the American support groups had little bother in collecting the much-needed cash.

1969 ended as it began - violently. Throughout the late autumn and early winter a succession of riots marked an increase in sectarian violence. The army inevitably became involved and the para-military elements on both sides found an active role for themselves in the brick and bottle skirmishes of the Belfast ghettoes. On the streets events were moving fast, but in terms of reforms the inevitable slow speed of legislation meant little political progress. Bricks and bottles were soon to give way to guns and bombs.

1970-71

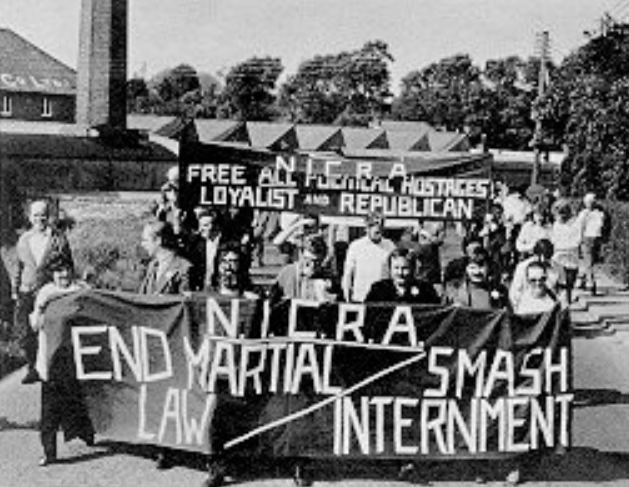

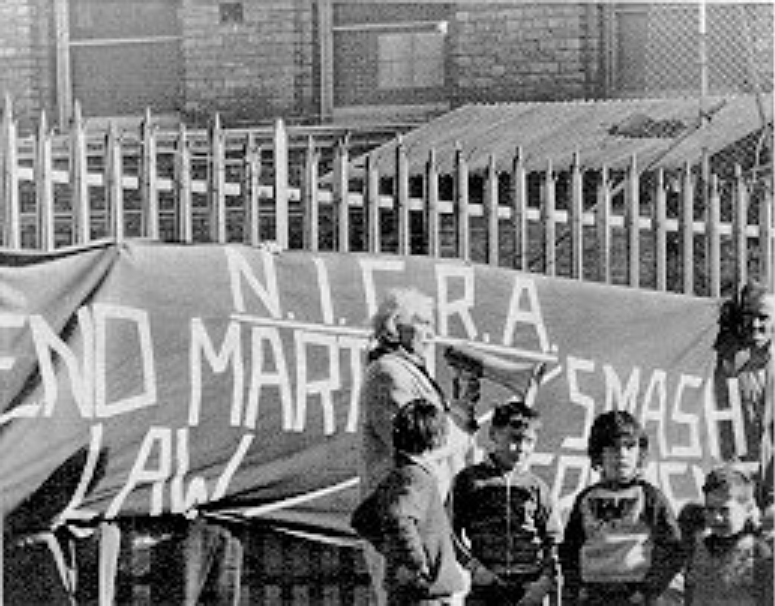

In January 1970 Captain O'Neill became a life peer, the UDR came into existence and the RUC returned unarmed onto the Falls Road and the Bogside. A new set of political props had arrived on the Northern Ireland stage but the theme of the drama was all too familiar. Up in Stormont the Unionists were at it again. Their Public Order [Amendment] Act was due for passing. This Act made it an offence to take part in an unlawful procession, and it also became an offence to sit, kneel or lie on the road in a demonstration. It was also illegal to occupy a building by way of protest and the period of notice of a march to the police was extended from 48 to 72 hours. Briefly it was an attempt to force civil rights and other demonstrations off the streets so that no political pressure could be put on the Government except by the ineffective minority inside parliament. NICRA was aware that it had no proper representation inside parliament in the manner of a political party and it was therefore imperative to protect its only method of legitimate political demand, the street demonstration. On February 7th it organised 9 demonstrations in Northern Ireland and 15 throughout Britain in protest against the Act.

More Trouble Inside

But there was more trouble inside the organisation. In December three members of the executive, Dr. Conn McCluskey, John Donaghy and Brid Rodgers, had complained of the left wing influences in the organisation and had said that certain members of the executive were making unreasonable demands of the movement at that time.

It was a clear reference to the influences of the PD members on the executive. The three objectors represented the opposite end of the political spectrum. Civil rights must be Catholic rights and those arguing for socialist rights had no place on the executive. It was the old problem of determining who should have political priority in demanding both the type of rights and in making pre-conditions as to whom those rights should benefit most.

Political Fresh Air

The civil rights demands raised many problems. The old Nationalist - Unionist division in Northern Ireland had stifled political thought for 50 years and in the breath of political fresh air which NICRA brought to the country a vast array of hibernating political animals were awakened.

Their first instinct was to follow the civil rights band wagon, but on careful reflection several people realised that a non-party-political demand like civil rights was not in keeping with their pre-determined political views, and, unable to swing NICRA into a definite party political position, they generally left, unaware that a civil rights organisation by the nature of its demands could retain credibility only as long as it remained aloof from party political lines.

That NICRA should be classified as an anti-unionist organisation was a reasonable expectation in the light of Northern politics. But that several political groups should have anticipated it as an organisation which could cater for their political ideology was a reflection of the lack of political progressive thought in Northern Ireland. If NICRA achieved nothing else in this period it certainly forced all anti-Unionists to develop their political thoughts beyond the stage of negative politics of simple anti-unionism.

They could then work out their positions in relation to the more normal political cleavage of left and right. Begun as pro-civil rights, NICRA had become identified as anti-Unionist and it soon became a clearinghouse for the politically confused who were shocked to discover that not only was NICRA not in line with their brand of anti-Unionism, it was not even deliberately anti-Unionist - it was pro - civil rights, and only the anti-civil rights stance of the Unionist party brought the two into conflict.

Decline of Mass Movement

Its success as a clearing house for the politically confused led to NICRA's decline as a mass movement. The thousands who marched in 1968 and 1969 found it easy to rally around the NICRA banners demanding one man, one vote, but the granting of this and other demands brought NICRA from a political position of visible discrimination in Northern Ireland into a situation of invisible semi-democracy. And although semi-democracy was a major step forward, the fact that something like one man, one vote was not a tangible asset meant that many people passed through the marching ranks of NICRA into a political party. There they found what they had presumably been looking for - the political mechanism of fighting for power. NICRA was not intended to fight for political power and the peak of its success would have been -and would still be - a totally democratic society in which its role could be reduced to that of watch dog.

But many people associated with NICRA in its early days failed to recognise this and it was only the changing political situation of 1970 which slowly brought home the realisation that those people who wanted the Unionists out of office would have to find a political party into which they could channel their efforts.

The Monolith is Destroyed

The more normal political situation in Britain and the South of Ireland have meant that the civil rights organisations there have never had the same difficulties as NICRA in this respect. The concept of a civil rights organisation designed to monitor the Government's performance on democratic issues was readily accepted in both states and it was only the political immaturity of the Northern Nationalist population which caused initial confusion over NICRA's position. In a similar way NICRA also helped the Unionists to sort out their respective political beliefs. United by political inactivity, the Unionist Party split in several directions when the pressure of the civil rights campaign was applied and the once monolithic party has never been united since 1969.