More languages

More actions

Verda.Majo (talk | contribs) Tag: Visual edit |

Verda.Majo (talk | contribs) Tag: Visual edit |

||

| Line 11: | Line 11: | ||

Korea "had been a single nation for at least 1,000 years with a continuous society, language and political system" and "remained independent despite 500 years of efforts of bigger powers to dominate it" until the Japanese annexation in 1910, and later the post-World War II division of Korea into North and South.<ref name=":14" /> | Korea "had been a single nation for at least 1,000 years with a continuous society, language and political system" and "remained independent despite 500 years of efforts of bigger powers to dominate it" until the Japanese annexation in 1910, and later the post-World War II division of Korea into North and South.<ref name=":14" /> | ||

Before Japan’s defeat in the Pacific War in August 1945, Korea had a rice-based colonial economy that had been tightly controlled in the interest of creating a rice surplus to feed Japan. In particular, the southern part of the peninsula was predominantly agricultural and supplied a greater portion of the food for all of Korea. It was considered the “rice bowl” of the country. Since rice came mainly from South Korea, the southern part of the Korean peninsula maintained a much higher population density.<ref name=":15">Kim Jinwung. A ''Policy of Amateurism: The Rice Policy of the U.S. Army Military''. Government in Korea, 1945-1948. https://kj.accesson.kr/assets/pdf/8153/journal-47-2-208.pdf</ref> | Before Japan’s defeat in the Pacific War in August 1945, Korea had a rice-based colonial economy that had been tightly controlled in the interest of creating a rice surplus to feed Japan. In particular, the southern part of the peninsula was predominantly agricultural and supplied a greater portion of the food for all of Korea. It was considered the “rice bowl” of the country. Since rice came mainly from South Korea, the southern part of the Korean peninsula maintained a much higher population density.<ref name=":15">Kim Jinwung. A ''Policy of Amateurism: The Rice Policy of the U.S. Army Military''. Government in Korea, 1945-1948. Korea Journal, Summer 2007.https://kj.accesson.kr/assets/pdf/8153/journal-47-2-208.pdf</ref> | ||

===US Occupation=== | ===US Occupation=== | ||

| Line 25: | Line 25: | ||

According to Richard Robinson, who had been working as a historian for the military during the occupation, the official American military history of the occupation is "highly prejudiced and inaccurate" adding that the official U.S. histories were "written upon explicit orders not even to imply criticism of anything American" and says that "if the truth were known, the American occupation of South Korea was incredibly bungled by an incompetent and corrupt administration—all in the name of American democracy."<ref name=":5">Robinson, Richard. Cited in Chung, Yong Wook. ''From Occupation to War; Cold War Legacies of US Army Historical Studies of the Occupation and Korean War''. Korea Journal, vol. 60, no. 2 (summer 2020): 14–54. doi: 10.25024/kj.2020.60.2.14 © The Academy of Korean Studies, 2020 URL: https://kj.accesson.kr/assets/pdf/8518/journal-60-2-14.pdf</ref> Robinson had his work suppressed as he expressed criticism of the U.S. military government's failures in Korea and eventually was compelled to leave the country.<ref name=":5" /><ref>{{News citation|author=김환균|newspaper=미디어오늘 (Media Today)|title='미국의 배반'이 미국에서 금서가 된 이유. (Why "American Betrayal" is Banned Reading in the U.S.)|date=2004-08-09|url=http://www.mediatoday.co.kr/news/articleView.html?idxno=25874|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220724050252/http://www.mediatoday.co.kr/news/articleView.html?idxno=25874|archive-date=2022-07-24|retrieved=2022-07-24}}</ref> | According to Richard Robinson, who had been working as a historian for the military during the occupation, the official American military history of the occupation is "highly prejudiced and inaccurate" adding that the official U.S. histories were "written upon explicit orders not even to imply criticism of anything American" and says that "if the truth were known, the American occupation of South Korea was incredibly bungled by an incompetent and corrupt administration—all in the name of American democracy."<ref name=":5">Robinson, Richard. Cited in Chung, Yong Wook. ''From Occupation to War; Cold War Legacies of US Army Historical Studies of the Occupation and Korean War''. Korea Journal, vol. 60, no. 2 (summer 2020): 14–54. doi: 10.25024/kj.2020.60.2.14 © The Academy of Korean Studies, 2020 URL: https://kj.accesson.kr/assets/pdf/8518/journal-60-2-14.pdf</ref> Robinson had his work suppressed as he expressed criticism of the U.S. military government's failures in Korea and eventually was compelled to leave the country.<ref name=":5" /><ref>{{News citation|author=김환균|newspaper=미디어오늘 (Media Today)|title='미국의 배반'이 미국에서 금서가 된 이유. (Why "American Betrayal" is Banned Reading in the U.S.)|date=2004-08-09|url=http://www.mediatoday.co.kr/news/articleView.html?idxno=25874|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220724050252/http://www.mediatoday.co.kr/news/articleView.html?idxno=25874|archive-date=2022-07-24|retrieved=2022-07-24}}</ref> | ||

==== People's | ==== USAMGIK disregards People's Committee's rice management, establishes rice "free market" ==== | ||

During Japanese colonial rule, the Japanese placed rigid controls on the people of Korea to build up a food surplus. When the U.S. forces arrived in South Korea, they found that "Japanese control over rice had been loosened or altogether abolished" and that instead, "the Korean People’s Republic (KPR) and people’s committees managed food stocks, and according to American accounts, 'after the Koreans drove the Japanese police out, [the leaders of the KPR and people’s committees] took over the rice collection machinery and were operating it successfully when the Americans arrived.'"<ref name=":15" /> | During Japanese colonial rule, the Japanese placed rigid controls on the people of Korea to build up a food surplus. When the U.S. forces arrived in South Korea, they found that "Japanese control over rice had been loosened or altogether abolished" and that instead, "the Korean People’s Republic (KPR) and people’s committees managed food stocks, and according to American accounts, 'after the Koreans drove the Japanese police out, [the leaders of the KPR and people’s committees] took over the rice collection machinery and were operating it successfully when the Americans arrived.'"<ref name=":15" /> As the Americans largely did not acknowledge the authority of the People's Committees and were trying to establish an anti-communist government in South Korea, they struck down the management system that had been operating under the People's Committees and replaced it with a "free market" in rice. In Ordinance 19, USAMGIK describes this as "giving to every man, woman and child within the country equal opportunity to enjoy his just and fair share of great wealth which this beautiful nation has been endowed".<ref>Office of the Military Governor, United States Army Forces in Korea. [https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/USAMGIK_Ordinance_19 Ordinance Number 19]. 1945-10-30. </ref><ref name=":15" /> | ||

In "A Policy of Amateurism: The Rice Policy of the U.S. Army Military''"'', Kim Jinwung describes the results of the free market policy of the USAMGIK:<blockquote>The immediate effect of the free market policy was a steep rise in the price of rice and resultant hoarding and speculation. Poor distribution of food led to food shortages and hunger in cities, despite a bumper harvest in 1945. Additionally, the rice-based South Korean economy inevitably began to suffer from massive inflation. It was quite natural then that the black-market should grow and prosper; it was expected that the lure of black market prices would stimulate the flow of rice into the black market. The result was that “rice disappeared almost entirely from the market.”13 Through its free market policy, the U.S. military government lost the main strength of the South Korean economy—its ability to extract large surpluses of grain—and caused in its stead spiraling inflation, near starvation in early 1946, and a general economic breakdown. The price of a bushel of rice increased from 9.4 yen in September 1945 to 2,800 yen in September 1946.14 Landlords, police and other government officials, and wealthy individuals engaged in speculation on a wholesale basis.<ref name=":15" /></blockquote>In the wake of this policy, USAMGIK was "flooded with complaints and petitions from Koreans demanding that price control and rationing be resumed and that the American military government take drastic action to stop rice hoarding."<ref name=":15" /> However, it seemed to many that USAMGIK was "reluctant to move against the principal hoarders" due to them being Korean businessmen who the government who had been relying on for advice.<ref name=":15" /> By 1946, the U.S. rescinded the free market and implemented rice rationing. A U.S. summation of the U.S. army military government activities in Korea stated that public attention was "focused on the threat of hunger" at this time.<ref>Commander-in-Chief, United States Army Forces, Pacific. ''[https://www8.cao.go.jp/okinawa/okinawasen/pdf/b0604002_09/b0604002_09.pdf Summation of United States Military Government Activities in Korea, No. 6].'' March 1946. </ref> As the situation continued, U.S. rice rations eventually fell to half of the ration size that had been received under the Japanese colonial administration during World War II, and newspapers published accounts of famine and starvation, further disaster only being averted by eventual shipments of U.S. grains as emergency relief. In addition, "the deteriorating food situation forced the Americans to revive the old Japanese rice collection system" which was unpopular with farmers.<ref name=":15" /> The USAMGIK eventually formed local boards composed of local police officials, elders, businessmen, and landlords approved by the USAMGIK to manage the collection of rice quotas, but created no system for appeal to adjust the quotas. Under this program, many farmers were arrested or faced violence for not meeting their quotas.<ref name=":15" /> | |||

==== Re-appointment of Japanese colonial era officials under U.S. Military Government ==== | ==== Re-appointment of Japanese colonial era officials under U.S. Military Government ==== | ||

| Line 46: | Line 48: | ||

According to The Jeju 4·3 Incident Investigation Report, "In around the middle of November 1948, uncompromising repression operations were carried out. Under these operations, a curfew was imposed on the residents of the upland areas and if anyone broke it, he or she was executed without exception. From the middle of November 1948 to February 1949, for about four months, the anti-guerrilla expeditions burned down the upland villages and killed the residents collectively. [...] During this period, the casualties were the highest and most of the upland villages were literally burnt to the ground."<ref>{{Citation|author=Jeju 4·3 Peace Foundation|year=2003|title=The Jeju 4·3 Incident Investigation Report|page=469|pdf=https://jeju43peace.or.kr/cmm/fms/FileDown.do?atchFileId=FILE_00000000000071265Cu0&fileSn=0|publisher=The National Committee for Investigation | According to The Jeju 4·3 Incident Investigation Report, "In around the middle of November 1948, uncompromising repression operations were carried out. Under these operations, a curfew was imposed on the residents of the upland areas and if anyone broke it, he or she was executed without exception. From the middle of November 1948 to February 1949, for about four months, the anti-guerrilla expeditions burned down the upland villages and killed the residents collectively. [...] During this period, the casualties were the highest and most of the upland villages were literally burnt to the ground."<ref>{{Citation|author=Jeju 4·3 Peace Foundation|year=2003|title=The Jeju 4·3 Incident Investigation Report|page=469|pdf=https://jeju43peace.or.kr/cmm/fms/FileDown.do?atchFileId=FILE_00000000000071265Cu0&fileSn=0|publisher=The National Committee for Investigation | ||

of the Truth about the Jeju April 3 Incident}}</ref> A combination of government forces and violent far-right paramilitary groups, notably the far-right anti-communist Northwest Youth League, carried out these attacks.<ref name=":7" /> | of the Truth about the Jeju April 3 Incident}}</ref> A combination of government forces and violent far-right paramilitary groups, notably the far-right anti-communist Northwest Youth League, carried out these attacks.<ref name=":7" /> | ||

[[File:Jeju 4.3 Camellia flower.png|thumb|The camellia flower can be seen in the island of Jeju as a symbol of the 4.3 incident. Above: A camellia flower pin. Below: Camellia flowers forming the shape of Jeju Island.]] | |||

===== Death toll of Jeju massacre and long-term imprisonment of Jeju islanders ===== | ===== Death toll of Jeju massacre and long-term imprisonment of Jeju islanders ===== | ||

Revision as of 02:09, 27 July 2022

| South Korea 대한민국 | |

|---|---|

|

Flag | |

| Capital | Seoul |

| Official languages | Korean |

| Dominant mode of production | Capitalism |

| Government | Unitary Corporatocratic Republic |

• President | Moon Jae-in |

• Prime Minister | Kim Boo-kyum |

• Speaker of the National Assembly | Park Byeong-seug |

| History | |

• First Republic | 1948 August 15th |

| Area | |

• Total | 100,363 km² |

| Population | |

• 2019 estimate | 51,709,098 |

| Currency | Korean Republic won |

The Republic of Korea (ROK), commonly called South Korea, is a U.S. puppet state on the southern portion of the Korean Peninsula. The northern part of the peninsula is governed by the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK), commonly called North Korea.

Since the ROK is a bourgeois republic (a dictatorship of the bourgeoisie, in Marxist language) is is riddled with corruption and political scandals. All four living former South Korean presidents have been sentenced to prison for various crimes ranging from abuse of authority to bribery and embezzlement.[1][2][3][4][5]

History

Background: Early history, Japanese colonial era, pre-US occupation

See: Korea

Korea "had been a single nation for at least 1,000 years with a continuous society, language and political system" and "remained independent despite 500 years of efforts of bigger powers to dominate it" until the Japanese annexation in 1910, and later the post-World War II division of Korea into North and South.[6]

Before Japan’s defeat in the Pacific War in August 1945, Korea had a rice-based colonial economy that had been tightly controlled in the interest of creating a rice surplus to feed Japan. In particular, the southern part of the peninsula was predominantly agricultural and supplied a greater portion of the food for all of Korea. It was considered the “rice bowl” of the country. Since rice came mainly from South Korea, the southern part of the Korean peninsula maintained a much higher population density.[7]

US Occupation

After Kim Il-sung liberated Korea from the Japanese Empire, in an "outburst of meetings and organizing" that "came out into the open all over Korea" after Japanese surrender, activists throughout the Korean peninsula began to plan and organize to replace Japanese rule and dominance. Groups of local people gathered in most villages and cities and sought ways to replace the police and pro-Japanese administrators with people who had resisted Japanese rule.[6] A left-leaning nationwide organization established by Koreans known as the Alliance for National government as well as many local People's Committees enjoyed widespread popular support throughout the country. However, the U.S. Military Government in Korea (USAMGIK) did not recognize the new state declared by the People’s Committees, and Korea was divided across the 38th parallel by two American officers who had never been to Korea.[8] The U.S. occupation of the southern half of Korea was announced in Proclamation No. 1 by General of the Army Douglas MacArthur on Sept. 7, 1945, with the statement that “All powers of Government over the territory of Korea south of 38 degrees north latitude and the people thereof will be for the present exercised under my authority.”[9]

In "A Policy of Amateurism: The Rice Policy of the U.S. Army Military", Kim Jinwung writes:

When news arrived that the United States was planning to occupy southern Korea, [Yeo Un-hyeong's Committee for the Preparation of Korean Independence] called a national convention in Seoul on September 6 to give his regime the stamp of legitimacy. Yeo and his followers wanted to quicken the process of establishing a new government before the Americans arrived. Yeo proclaimed the establishment of the Korean People’s Republic, with a cabinet that included distinguished nationalists of all political persuasions, right and left. But the body was clearly influenced by the left, with Communists playing key roles.[7]

However, the U.S. refused to recognize this organization, and General John R. Hodge, the Commanding General of U.S. Army Forces in Korea, outlawed the people’s committees and created new local councils under conservative control.[7] In an article titled "People's Republic of Korea: Jeju, 1945-1946", Jay Hauben describes the situation:

On Sept. 8, 21 US warships arrived in Incheon to supervise in the name of the Allies the surrender of the Japanese Governor-General of Korea and the 200,000 Japanese military personnel and their equipment and property south of the 38th parallel. US General John Hodge commanded the US landing. The US party was met by an English speaking committee of the PRK [People's Republic of Korea] to welcome it to Korea in the name of the people and newly emerging government of Korea. General Hodge refused to meet with them. His mission was to head the United States Military Government In Korea (USAMGIK) and he would not accept that there was already a newly forming government of Korea.[6]

Due to the People’s Committees enjoying such widespread popular support, the USAMGIK resorted to dissolved the committees by force so that the U.S. could effectively rule the country.[10] As noted by Hauben, "The USAMGIK had as its mission to prevent a Korean government friendly to socialism or communism or leftism in general. That mission required that the left leaning majority of the Korean people had to be diverted."[6]

Following General MacArthur's Proclamation No. 1, the USAMGIK became the official ruling body of South Korea (in the eyes of the U.S.), from 1945 to 1948, until the establishment of the Republic of Korea on Aug. 15, 1948. Through this series of events, the Korean Peninsula was divided along the 38th parallel, the South was occupied by the United States, the People's Committees were suppressed, many Japanese colonial era collaborator police and officials were placed back into positions of power, and a fascist dictatorship led by Harvard graduate Syngman Rhee was installed.[11]

Suppressed criticism in official U.S. military history of Korean War and U.S. occupation of Korea

In the work From Occupation to War: Cold War Legacies of US: Army Historical Studies of the Occupation and Korean War, Seoul National University professor Chung Yong Wook writes that "a divergent understanding" of this era "was repressed or rooted out by force in the US and around the ‘free world'" due to the official U.S. history of the war being written in the context of the emerging Cold War. Military historian Richard Robinson, who wrote a work critical of the U.S. role in Korea, Betrayal of a Nation, was unable to find a publisher for his work and it remained in manuscript form. I.F. Stone's work The Hidden History of the Korean War (1952) which was also critical of U.S. conduct in Korea was removed from many libraries. Professor Chung notes that "military historians were not, in essence, allowed to criticize information given to them, nor did they have leeway in interpreting and critiquing facts, they were left only to describe sanitized history" at all stages of the information-gathering and history-writing process.[12]

According to Richard Robinson, who had been working as a historian for the military during the occupation, the official American military history of the occupation is "highly prejudiced and inaccurate" adding that the official U.S. histories were "written upon explicit orders not even to imply criticism of anything American" and says that "if the truth were known, the American occupation of South Korea was incredibly bungled by an incompetent and corrupt administration—all in the name of American democracy."[13] Robinson had his work suppressed as he expressed criticism of the U.S. military government's failures in Korea and eventually was compelled to leave the country.[13][14]

USAMGIK disregards People's Committee's rice management, establishes rice "free market"

During Japanese colonial rule, the Japanese placed rigid controls on the people of Korea to build up a food surplus. When the U.S. forces arrived in South Korea, they found that "Japanese control over rice had been loosened or altogether abolished" and that instead, "the Korean People’s Republic (KPR) and people’s committees managed food stocks, and according to American accounts, 'after the Koreans drove the Japanese police out, [the leaders of the KPR and people’s committees] took over the rice collection machinery and were operating it successfully when the Americans arrived.'"[7] As the Americans largely did not acknowledge the authority of the People's Committees and were trying to establish an anti-communist government in South Korea, they struck down the management system that had been operating under the People's Committees and replaced it with a "free market" in rice. In Ordinance 19, USAMGIK describes this as "giving to every man, woman and child within the country equal opportunity to enjoy his just and fair share of great wealth which this beautiful nation has been endowed".[15][7]

In "A Policy of Amateurism: The Rice Policy of the U.S. Army Military", Kim Jinwung describes the results of the free market policy of the USAMGIK:

The immediate effect of the free market policy was a steep rise in the price of rice and resultant hoarding and speculation. Poor distribution of food led to food shortages and hunger in cities, despite a bumper harvest in 1945. Additionally, the rice-based South Korean economy inevitably began to suffer from massive inflation. It was quite natural then that the black-market should grow and prosper; it was expected that the lure of black market prices would stimulate the flow of rice into the black market. The result was that “rice disappeared almost entirely from the market.”13 Through its free market policy, the U.S. military government lost the main strength of the South Korean economy—its ability to extract large surpluses of grain—and caused in its stead spiraling inflation, near starvation in early 1946, and a general economic breakdown. The price of a bushel of rice increased from 9.4 yen in September 1945 to 2,800 yen in September 1946.14 Landlords, police and other government officials, and wealthy individuals engaged in speculation on a wholesale basis.[7]

In the wake of this policy, USAMGIK was "flooded with complaints and petitions from Koreans demanding that price control and rationing be resumed and that the American military government take drastic action to stop rice hoarding."[7] However, it seemed to many that USAMGIK was "reluctant to move against the principal hoarders" due to them being Korean businessmen who the government who had been relying on for advice.[7] By 1946, the U.S. rescinded the free market and implemented rice rationing. A U.S. summation of the U.S. army military government activities in Korea stated that public attention was "focused on the threat of hunger" at this time.[16] As the situation continued, U.S. rice rations eventually fell to half of the ration size that had been received under the Japanese colonial administration during World War II, and newspapers published accounts of famine and starvation, further disaster only being averted by eventual shipments of U.S. grains as emergency relief. In addition, "the deteriorating food situation forced the Americans to revive the old Japanese rice collection system" which was unpopular with farmers.[7] The USAMGIK eventually formed local boards composed of local police officials, elders, businessmen, and landlords approved by the USAMGIK to manage the collection of rice quotas, but created no system for appeal to adjust the quotas. Under this program, many farmers were arrested or faced violence for not meeting their quotas.[7]

Re-appointment of Japanese colonial era officials under U.S. Military Government

The USAMGIK had a policy of rehiring officers from the Japanese colonial era, which it tried to justify by the need to implement effective governance. This failure to prosecute officers who had collaborated with the Japanese and re-instatement of their power increased public resentment against the U.S. regime.[10] Instead of fully enjoying their independence, people were being victimized by the same oppressive police officers and corrupt public officials as under Japanese colonial authority.[17]

USMGIK clashes with People's Committees

Richard Robinson, the chief of the Public Opinion Section of the Department of Information of the USAMGIK, who had been present in Korea and contributing to the official U.S. military historical record at the time, later gave his observations about the People's Committees and the USAMGIK's policy of rehiring officers from the Japanese colonial era:

It was safe to say that for the most part the local People's Committees in these early days were of the genuine grassroots democratic variety and represented a spontaneous urge of the people to govern themselves. . . . They resented orders from the Military Government to turn the administration of local government over to American Army officers and their appointed Korean counterparts, many of whom were considered to be Japanese collaborators. It seemed like a reversion to what had gone before. Bloodshed ensued in many communities as local People's Committees defied the Military Government and refused to abandon government offices. Koreans and Americans met in pitched battles, and not a few Koreans met violent death in the struggle.[18]

Robinson then gives an example of an incident which he refers to as "typical" of this period. According to Robinson, in the small community of Namwon in North Jeolla province, the Japanese had turned over considerable property to the local People's Committee just prior to the arrival of the Americans. The U.S. military government then demanded the property, but the People's Committee refused to turn it over to the U.S. military government. Robinson states that five leaders of the Committee were arrested by the local Korean police, adding that "the police chief was captured and beaten by Committee members and the police station attacked by a large crowd of irate citizens." He says that the station was guarded by American troops, and that when the Koreans refused to disband, "the Americans advanced with fixed bayonets," resulting in two Koreans being killed and several injured.[18]

First Republic

The First Republic was the government of South Korea from August 1948 to April 1960. Syngman Rhee ruled for the entire existence of the first republic. The first republic was characterized by Rhee's authoritarianism and corruption, limited economic development, strong anti-communism, and by the late 1950s, by growing political instability and public opposition to Rhee.

Jeju People's Committee

After liberation from Japanese colonization, the Jeju People’s Committee was formed with the head of the Farmers Guild and the Fishermen’s Guide as its leaders. According to the Jeju 4.3 Peace Foundation, "In every aspect, the Jeju People’s Committee was the only political party and the only government in Jeju" after liberation from the Japanese. E. Grant Meade, a USAMGIK officer, said, “The Jeju People’s Committee was the only political party in the island and the only organization acting like a government.”[17] The committees had the respect and support from most villagers. Committee members were known in their communities from their long years as school teachers, union leaders and for resistance to Japanese abuses or for their organizing work in Japan. When the USAMGIK arrived on Jeju, it found that the Jeju People’s Committee and all the village and county People’s Committees were functioning successfully as a de facto government with popular support. The USAMGIK did not disturb or challenge this de facto government. This was unusual because the USAMGIK had as its mission to insure that a right leaning government hostile to socialism emerged in Korea.[6]

Jeju Uprising and Massacre

In 1948, in a series of events known variously as the Jeju Uprising, the Jeju 4.3 Incident, and the Jeju Massacre, an uprising occurred on Jeju Island, followed by a scorched earth style retaliation undertaken by government forces and right-wing paramilitary groups to root out communist influence on the island. The Jeju massacre was the second largest massacre in South Korea's modern history,[20] the death toll listed by the Jeju 4.3 Peace Foundation being approximately 30,000 people, or one-tenth of the island's population.[21]

Although the People’s Committees in other regions were either dissolved by the USAMGIK or operated under different names, the Jeju People’s Committee remained intact and enjoyed strong support. This was largely due to the pro-Japanese faction being relatively weak in Jeju. Many people who had fought for independence against the Japanese returned to their hometowns and became members of the People’s Committee in Jeju.[17] However, Many Jeju islanders resisted the division of the Korean Peninsula and strongly protested the first election that was scheduled for May 10, 1948, that would confirm the formation of the Republic of Korea south of the 38th parallel. Their resistance to the division of the peninsula and the establishment of the Southern regime triggered a brutal suppression by government forces.

According to The Jeju 4·3 Incident Investigation Report, "In around the middle of November 1948, uncompromising repression operations were carried out. Under these operations, a curfew was imposed on the residents of the upland areas and if anyone broke it, he or she was executed without exception. From the middle of November 1948 to February 1949, for about four months, the anti-guerrilla expeditions burned down the upland villages and killed the residents collectively. [...] During this period, the casualties were the highest and most of the upland villages were literally burnt to the ground."[22] A combination of government forces and violent far-right paramilitary groups, notably the far-right anti-communist Northwest Youth League, carried out these attacks.[19]

Death toll of Jeju massacre and long-term imprisonment of Jeju islanders

Because the facts of the Jeju massacre were officially suppressed for over fifty years, only coming to light in January 2000 when a Special Act was decreed by the South Korean Government calling for an official investigation of the incident, an official death toll could not be established until that time. Additionally, discoveries of previously unknown victims, such as the mass grave uncovered in 2008 near Jeju Airport, illustrate the difficulty of calculating the massacre's true toll.[20] According to a report by the National Commission on the Jeju April 3 Incident, 25,000 to 30,000 people were killed or simply vanished, with upwards of 4,000 more fleeing to Japan as the government sought to quell the uprising. As the island’s population was at most 300,000 at the time, the official toll was one-tenth of the inhabitants. However, some Jeju people claim that as many as 40,000 islanders were killed in the suppression.[20] Some estimates claim as many as 60,000 people may have been killed by the end of these events.[23] The 30,000 death figure, or one in every 10 Jeju residents at the time, is a common figure given for how many people lost their lives during this period, and is the one cited on the Jeju 4.3 Peace Foundation website.[21]

One result of the decades-long suppression of the facts of the massacre is the long-term imprisonment of Jeju islanders arrested on suspicion of being communists during the conflict. Many of those arrested on these charges died in captivity. Others remained in prison for up to 20 years, and those who had been released were not cleared of their criminal records, and were ostracized by the community or disadvantaged in their job applications for having criminal records. Decades after being arrested, some of the remaining victims had their names legally cleared of the charges in 2019, due to a ruling that found that the military court of the time did not follow proper legal procedures, made groundless charges, and that there were no court records found from the time explaining why those arrested were given such harsh sentences.[24]

1950-1953: The Korean War, Fatherland Liberation War, 6.25 War

See also: Korean War, List of atrocities committed by the United States of America#Korean War

This period is generally referred to in English as the "Korean War", in DPRK as the "Fatherland Liberation War" (Korean: 조국해방전쟁), and in South Korea as the "6.25 War" (Korean: 6·25 전쟁). In China it is sometimes referred to as the "Korean War", and some specific battles are referred to as the "War to Resist U.S. Aggression and Aid Korea" (Chinese: 抗美援朝战争). This period is also referred to by some in English as "The Forgotten War" or "The Unknown War."

In the U.S., the war was initially described as a "police action" as the United States never formally declared war on its opponents.[25] According to the U.S. Department of State's Office of the Historian, "When North Korea invaded South Korea in June 1950, the United States sponsored a "police action"—a war in all but name—under the auspices of the United Nations. The Department of State coordinated U.S. strategic decisions with the other 16 countries contributing troops to the fighting. In addition, the Department worked closely with the government of Syngman Rhee, encouraging him to implement reform so that the UN claim of defending democracy in Korea would be accurate." The U.S. Department of State's description of the war notes that "The Korean War was difficult to fight and unpopular domestically" and that "The American public tired of a war without victory."[26]

Support for North among South Koreans during the war

In 1950, when the DPRK attempted to reunify the country, Rhee's forces retreated and killed at least another 60,000 supposed communist sympathizers.[28]

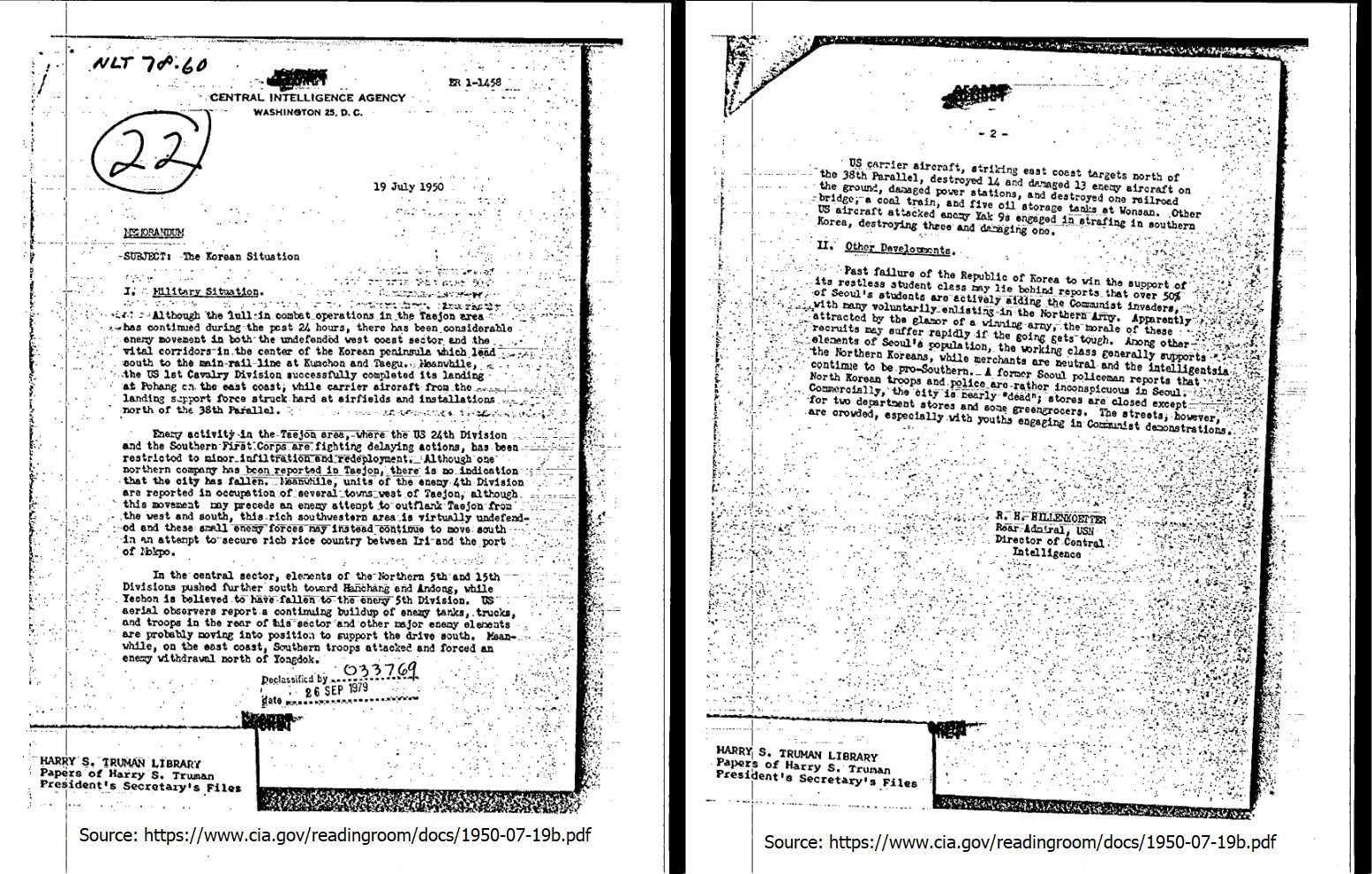

In a 1950 CIA memorandum, after the Northern Army had taken over Seoul, Central Intelligence Director and U.S. Navy Rear Admiral R.H. Hillenkoeter reported that "over 50% of Seoul's students are actively aiding the Communist invaders, with many voluntarily enlisting in the Northern Army" and that among Seoul's population, "the working class generally supports the Northern Koreans, while merchants are neutral and the intelligentsia continue to be pro-Southern," adding that the streets of Seoul were "crowded [...] with youths engaging in Communist demonstrations.[27]

According to Kim Sin Gyu, a North Korean correspondent present in Seoul at the time, speaking in an interview: "When the city was first liberated, the citizens of Seoul welcomed the Korean People's Army. I remember hearing people say, 'We heard the North Korean communist soldiers were a monstrous rabble, with the horns of devils and red faces. But seeing them now, they are the same as us. The soldiers are young and brave and handsome.'"[29]

Misconduct and killing of civilians by U.S. forces during the war

See: List of atrocities committed by the United States of America#Korean War

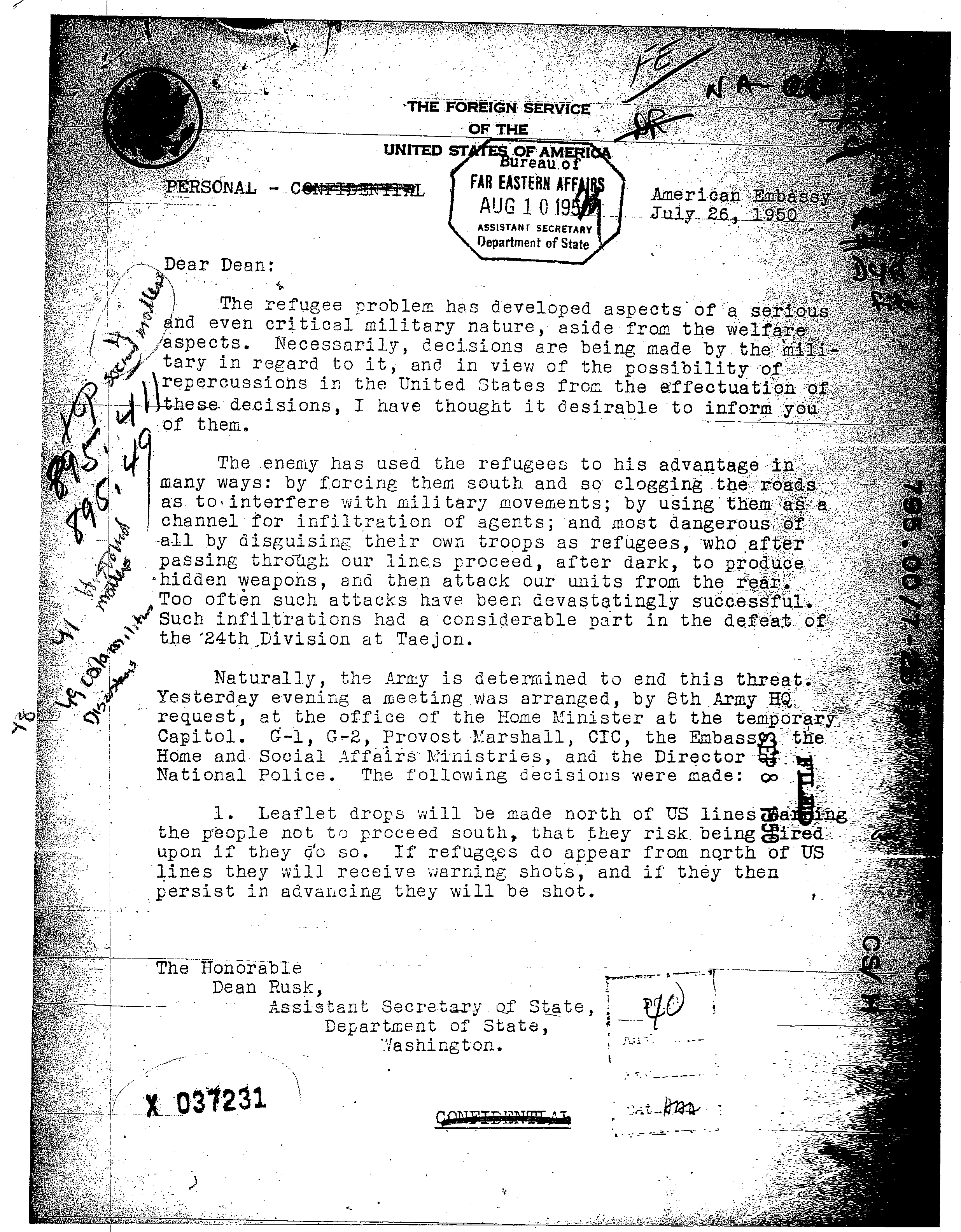

During the Korean War, U.S. troops killed large numbers of Korean civilians and engaged in copious firebombing with napalm, and, as was eventually revealed through declassified documents, had at certain times a policy of deliberately firing on South Korean refugee groups approaching its lines.[30] In an article of the Asia-Pacific Journal, Kim Dong choon writes that "Few are aware that the Korean authorities as well as US and allied forces massacred hundreds of thousands of South Korean civilians at the dawn of the Korean War".[31] There were also incidents of U.S. pilots ignoring their orders to stay within Korea and flying beyond its borders, strafing military targets in China and the Soviet Union.[29]

According to U.S. Naval Captain Walter Karig, in his book Battle Report: The War in Korea:

[W]e killed civilians, friendly civilians, and bombed their homes; fired whole villages with the occupants--women and children and ten times as many hidden Communist soldiers--under showers of napalm, and the pilots came back to their ships stinking of vomit twisted from their vitals by the shock of what they had to do.[32]

United States Air Force General Curtis LeMay, commander of the U.S.'s Strategic Air Command, gave a similar description of the U.S. military's conduct in Korea, saying:

[W]e went over there and fought the war and eventually burned down every town in North Korea [...] some way or another, and some in South Korea, too. We even burned down Pusan—an accident, but we burned it down anyway. The Marines started a battle down there with no enemy in sight. Over a period of three years or so, we killed off—what—twenty percent of the population of Korea as direct casualties of war, or from starvation and exposure?[33]

In addition to the U.S. military's practice of fire-bombing civilian targets and firing on refugees, many South Korean civilian casualties occurred due to the American soldiers' inability to tell apart North and South Koreans. As described by an anonymous U.S. officer on the U.S. Defense Department radio program called "Time for Defense", "What makes it so difficult over here is that you can't tell the damn North Koreans from the South Koreans, and that's caused a lot of slaughter."(audio file)[34] It may be argued that the policy of firing on groups of refugees was a result of this, as described in the 1988 documentary Korea: The Unknown War, which observes that "American troops found it difficult to distinguish friend from foe," and that "the North Koreans had infiltrated refugee columns, and in the ensuing confusion, innocent civilians became casualties." According to the documentary, one American general allegedly commented, "If they look organized, shoot at them."[29]

Emblematic of the U.S. policy of firing on groups of refugees is the incident of the Nogeun-ri massacre, also written as No Gun Ri (Korean: 노근리). The incident was little-known outside Korea until publication of an Associated Press story in 1999 in which U.S. veterans corroborated survivors' accounts, and details gradually became more widely known. In July 1950, American soldiers "machine-gunned hundreds of helpless civilians under a railroad bridge".[35] U.S. veterans spoke of 100 or 200 or "hundreds" dead and described "a preponderance of women, children and old men among the victims", while Korean witnesses said 300 were killed at the bridge and 100 in a preceding air attack. One Korean witness commented that "the American soldiers played with our lives like boys playing with flies." One of the U.S. veterans described it as "wholesale slaughter."[35]

Although this incident had gone unacknowledged for decades, in 2001 the U.S. Army acknowledged the killings, calling them a "regrettable accompaniment to a war." In 2006, it was revealed that among incriminating documents omitted from the 2001 U.S. report, there was a declassified letter from the U.S. ambassador in South Korea, dated the day the Nogeun-ri killings began, saying the Army had adopted a policy of firing on refugee groups approaching its lines.[30] Some U.S. veterans have also described other refugee killings as well, when U.S. commanders ordered their troops to shoot civilians as a defense against disguised enemy soldiers, and declassified U.S. Air Force reports allegedly show that pilots also sometimes deliberately attacked "people in white" (referring to white peasant garb), suspecting that disguised North Korean soldiers were among them.[35]

End of the First Republic

In 1960, Rhee was forced to resign due to mass protests across the nation after the body of a student killed by police was found floating in the harbor.[36]

Second, Third, Fourth, Fifth Republics and Military rule

After Rhee's resignation, bourgeois democracy was briefly restored under president Yun Bo-seon.[37] On 1961 May 16, General Park Chung-hee, the father of future president Park Geun-hye and former Japanese collaborator, took power in a military coup. Park ruled as a military dictator for 18 years and sent 320,000 troops to support the South Vietnamese puppet state in the Vietnam War. After Park's assassination on 26 October 1979, Chun Doo-hwan took power. In May 1980, protests against martial law began in Gwangju, which were met with special warfare troops. Up to 2,300 civilians were killed in the Gwangju massacre.[38]

Sixth Republic (1987-present)

The Sixth Republic was established in 1987 with Roh Tae-woo as its first president[39] and sixth president of South Korea from 1988 to 1993. Roh's election was the first direct presidential election in 16 years. His presidency was followed by Kim Young-sam (in office 1993–1998), the first civilian to hold the office in over 30 years. After this came the presidency of Kim Dae-jung (in office 1998–2003), known for his "Sunshine Policy" of engagement through dialogue and economic and cultural exchanges with North Korea.[40] This was followed by the presidencies of Roh Moo-hyun (in office 2003–2008), and Lee Myung-bak (in office 2008–2013).

South Korea's next president, Park Geun-hye (in office 2013–2017), is the daughter of former president Park Chung-hee. Park Geun-hye was in office as the 11th president of Korea until she was impeached and convicted on corruption charges following public demonstrations, commonly known as the Candlelight Revolution or Candlelight Demonstrations. She became the first South Korean president to be removed from power by impeachment, and was sentenced to 24 years in prison, but received a pardon and was released in 2021 after serving just under 5 years.[41] Park Geun-hye's presidency was followed by Moon Jae-in (in office 2017–2022). The 13th and current president of Korea is Yoon Suk-yeol of the conservative People Power Party.

Politics

NATO alliance

On February 26, 2022 (KST), former U.S. Secretary of Defense and Raytheon weapons manufacturer lobbyist, Mark Esper, delivered a speech at the 4th Think Tank 2022 Forum,[42] which is a think tank associated with Dr. Hak Ja Han Moon,[43] the wife of late millionaire[44] Rev. Sun Myung Moon, founder and self-proclaimed messiah of the generally right-wing, anti-communist Unification Church.[45] Speaking at this event, weapons industry lobbyist Esper emphasized the need for full cooperation between the U.S., South Korea, and Japan in the face of challenges posed by North Korea and China, saying:

It is said that the United States does not seek to build a, quote, "NATO for Asia". And I say, "Why not?" We should have lofty goals and high expectations and not let history and distance confound us. America's European allies overcame a brutal history to form a collective security arrangement to deal with Soviet Russia. There's no reason why the same can't happen in the Indo-Pacific as we increasingly face off against a recalcitrant North Korea and aggressive communist China.[46]

Esper stated that he is a "big believer" in the quadrilateral security dialogue known as "The Quad" a strategic security dialogue between Australia, India, Japan, and the United States that is maintained by talks between member countries, which Esper says is "rightly viewed as a unified response to China's rising military and economic power." He states, "I believe South Korea should be the next partner to join the Quad, transitioning it into the Quint."[46]

The former Raytheon lobbyist and defense company Epirus Inc. board member then went on to say that "America's allies and partners need to invest at least two percent of their GDP for defense and invest in the right capabilities," listing long-range precision strike capabilities, air and missile defenses, advanced submarines, and fifth generation fighter aircraft as examples, and noting that the Republic of Korea has already met this two percent mark.[46] Esper describes that these weapons investments will help the region deter Chinese and North Korean "aggression" and states that a "reinvigorated work plan with the DPRK should begin with the complete verifiable and irreversible denuclearization of the North."[42]

In June 2022, the South Korean president Yoon Suk-yeol declared he will participate in the 3rd NATO Summit of 2022.[47] The director of the National Security Office Kim Sung-han declared not much later that South Korea will establish a "diplomatic mission" to NATO in Brussels to coincide with President Yoon Suk-yeol's participation in the Summit. According to Sung-han, this mission will make South Korea "able to increase information sharing and strengthen our networks with NATO allies and partners and establish a Europe platform that is worthy of our [global] status".[48]

Unconverted long-term prisoners

Unconverted long-term prisoners is the North Korean term for northern loyalists imprisoned in South Korea who never renounced their support for DPRK. Many of them were arrested as spies, and some spent over 40 years in prison for their refusal to disavow the DPRK. While in prison, many of them were held in solitary confinement and subjected to extensive torture.[49] They were referred to only as "converts" and "converts-to-be", reflecting that refusal to convert was considered a non-option.[50] In the late 1990s, amnesty was declared for certain elderly and ill prisoners.

A 1995 article by Prison Legal News stated that one such prisoner, Kim Sun Myung, "had the unhappy distinction of being the world's longest held political prisoner," having served 43 years. A steadfast communist, Kim "could have been released decades earlier had he renounced his political beliefs" but remained unconverted instead. According to Prison Legal News, "Over the years Kim was beaten, starved, tortured, threatened with execution and watched his fellow prisoners die at the hands of South Korean government agents yet he did not capitulate" and that after his release, he commented "They say that when you hammer steel, it only gets harder. Well, when you hit people, you just turn them into enemies, and they become stronger." When asked about whether his faith in communism was shaken due to to events in Eastern Europe and the development of South Korea, he was "nonplused", and upon being shown skyscrapers in Seoul, he commented: "this kind of thing doesn't impress me, because there are still a lot of poor people. These tall buildings are the labor of poor people. Did you ever see any rich people digging on a construction site? The fight against poverty goes on."[52]

As the unconverted long-term prisoners began to be released, many of them sought repatriation to the DPRK. Some were able to return to DPRK, notably many of them in the year 2000,[53] but others remain in the South, being denied their requests for repatriation.[54] Those who returned to the DPRK were met with celebrations and fanfare welcoming them as heroes, while those remaining in South Korea generally live in poverty and in nursing homes, some without social security numbers.[50] Some, who are native to the South, have strained relationships with their families, who may have suffered legal repercussions as a result of having a convicted spy as a family member, or for not reporting them. Those who are from the North often have no family to connect with in the South. As the prisoners tend to be elderly, many of their immediate relatives have passed away. Those who oppose the repatriation of these former prisoners generally do so on grounds of demanding that DPRK start repatriating people back to the South as well. In 2003, South Korean director Kim Dong-won released Repatriation, a documentary about the unconverted prisoners and their experiences, based on more than 12 years and 800 hours of filming. The film documents their views on Korea's partition, their daily hardships as they attempt to adjust to South Korean society, as well as their struggle for repatriation.[55]

National Security Act

The National Security Act is a South Korean law enforced since 1948 with the avowed purpose "to secure the security of the State and the subsistence and freedom of nationals, by regulating any anticipated activities compromising the safety of the State." Behaviors or speeches in favor of the DPRK or communism can be punished by the National Security Law. In an article from The Diplomat, it was referred to as a "Cold War holdover" that "allows the government to selectively prosecute anyone who 'praises, incites or propagates the activities of an anti-government organization'" which the article describes as "a deliberately vague clause that broadly implies the North Korean state and its sympathizers." The article continues, explaining "Under Article 7, individuals have been prosecuted and imprisoned for merely possessing North Korean publications or satirically tweeting North Korean propaganda. In recent years this clause has been harshly criticized by Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, who claim the government abuses the law to repress dissenting voices."[56]

Rising anti-capitalism

In recent years, the term "Hell Joseon" or "Hell Korea" (Korean: 헬조선) has become popular to describe the social anxiety and discontent surrounding high unemployment and poor working conditions.[57][58]

South Korean media has also increasingly included narratives of class antagonism which have been poplar successes for Western audiences, with films such as Snowpiercer (2013)[59] and Parasite (2019)[60] and the popular TV show Squid Game (2021)[61][62][63]

With increasing economic stratification, social alienation, and lack of opportunity among young people entering the work force, South Korea has a rate of mental health issues and suicide that is among the highest in the developed world.[64] This undoubtedly is resulting in the development of class consciousness.

The bourgeoisie media (in South Korea and in the US) carefully ensures that all criticism of capitalism stops just short of providing concrete solutions, lest people become interested in socialism and its various successes around the world.

Labor militancy is also on the rise as 500k South Korean workers walk off in a one-day general strike, protesting against rampant exploitation by the gig economy, high costs of housing, and the highest annual working hours in the OECD.[65]

References

- ↑ "South Korea's troubling history of jailing ex-presidents" (2018-10-09). American Enterprise Institute.

- ↑ "Former South Korean president sentenced to prison" (2021-02-10). Deutsche Welle.

- ↑ Ex-president Roh Tae-woo to pay remainder of massive fine (2013-08-22). The Chosunilbo.

- ↑ "South Korea: President's impeachment on a background of political scandal" (2017-02-07). Perspective Monde.

- ↑ "South Korea ex-leader jailed for 15 years" (2018-10-05). BBC News.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 Jay Hauben (2011-08-20). "People's Republic of Korea: Jeju, 1945-1946" The Jeju Weekly. Archived from the original on 2022-07-23. Retrieved 2022-07-23.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 7.8 7.9 Kim Jinwung. A Policy of Amateurism: The Rice Policy of the U.S. Army Military. Government in Korea, 1945-1948. Korea Journal, Summer 2007.https://kj.accesson.kr/assets/pdf/8153/journal-47-2-208.pdf

- ↑ Don Oberdorfer, Robert Carlin (2014). The Two Koreas: A Contemporary History (p. 5). ISBN 9780465031238

- ↑ "Liberation from Japan in 1945" (2018). Jeju 4.3 Peace Foundation.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 "Who ruled over the Korean Peninsula?" (2018). Jeju 4.3 Peace Foundation. Retrieved 2022-07-23.

- ↑ "Syngman Rhee". Doopedia.

- ↑ Chung, Yong Wook. From Occupation to War; Cold War Legacies of US Army Historical Studies of the Occupation and Korean War. Korea Journal, vol. 60, no. 2 (summer 2020): 14–54. doi: 10.25024/kj.2020.60.2.14 © The Academy of Korean Studies, 2020. URL: https://kj.accesson.kr/assets/pdf/8518/journal-60-2-14.pdf Archive URL. Suppression of counter-narratives ("Abstract" p. 15, PDF p.1); "sanitized history" (p. 20, PDF p. 7)

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Robinson, Richard. Cited in Chung, Yong Wook. From Occupation to War; Cold War Legacies of US Army Historical Studies of the Occupation and Korean War. Korea Journal, vol. 60, no. 2 (summer 2020): 14–54. doi: 10.25024/kj.2020.60.2.14 © The Academy of Korean Studies, 2020 URL: https://kj.accesson.kr/assets/pdf/8518/journal-60-2-14.pdf

- ↑ 김환균 (2004-08-09). "'미국의 배반'이 미국에서 금서가 된 이유. (Why "American Betrayal" is Banned Reading in the U.S.)" 미디어오늘 (Media Today). Archived from the original on 2022-07-24. Retrieved 2022-07-24.

- ↑ Office of the Military Governor, United States Army Forces in Korea. Ordinance Number 19. 1945-10-30.

- ↑ Commander-in-Chief, United States Army Forces, Pacific. Summation of United States Military Government Activities in Korea, No. 6. March 1946.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 "Jeju’s political climate following liberation" (2018). Jeju 4.3 Peace Foundation.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Robinson, Richard. Cited in Mark J. Scher (1973) U.S. policy in Korea 1945–1948: A Neocolonial model takes shape. Bulletin of Concerned Asian Scholars, 5:4, 17-27, DOI: 10.1080/14672715.1973.10406346. https://doi.org/10.1080/14672715.1973.1040634 URL: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/14672715.1973.10406346

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 “Despite the Northwest Youth League lacking legal backing to exercise their power, President Rhee and the KDP allowed the group to use aggressive force against supposed Communists without restrictions. [...] Professor Bruce Cumings of the University of Chicago states that at the time, Jeju’s local government and police were comprised mostly of mainlanders who “worked together with ultra-rightest party terrorists,” otherwise known as the Northwest Youth League.”

Lauren Flenniken (2011-04-10). "The Northwest Youth League" The Jeju Weekly. Retrieved 2022-07-25. - ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 Song Jung Hee (2010-03-31). "Islanders still mourn April 3 massacre" The Jeju Weekly.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 "Background to the Jeju 4·3 Uprising and Massacre" (2018). Jeju 4.3 Peace Foundation. Archived from the original on 2022-07-23.

- ↑ Jeju 4·3 Peace Foundation (2003). The Jeju 4·3 Incident Investigation Report (p. 469). [PDF] The National Committee for Investigation of the Truth about the Jeju April 3 Incident.

- ↑ Ghosts of Cheju (2000-06-18). Newsweek. Archived from the original. Retrieved 2021-21-30.

- ↑ “The suit was filed by 18 plaintiffs who were jailed after being branded as communist insurgents ― with around 2,500 others ― during the ideological conflict that flared up on the southern island after Korea's independence from Japan. Many died in captivity. Even after surviving the massacre and imprisonment, the plaintiffs were ostracized by the community or disadvantaged in their job applications for having criminal records. [...] The plaintiffs demanded a retrial in 2017, saying they were arrested and imprisoned for up to 20 years without fair procedure. There were no court records found from the time explaining why the plaintiffs were given such harsh sentences.”

Lee Suh-yoon (2019-01-17). "Jeju massacre victims get their names cleared in court" The Korea Times. - ↑ Truman, Harry S. (29 June 1950). "The President's News Conference of June 29, 1950. Teachingamericanhistory.org. Archive link.

- ↑ A Short History of the Department of State. "NSC-68 and the Korean War." Office of the Historian, Foreign Service Institute, U.S. Department of State. URL: https://history.state.gov/departmenthistory/short-history/koreanwar Archive link.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 “Past failure of the Republic of Korea to win the support of its restless student class may lie behind reports that over 50% of Seoul's students are actively aiding the Communist invaders, with many voluntarily enlisting in the Northern Army. Apparently attracted by the glamor of a winning army, the morale of these recruits may suffer rapidly if the going gets tough. Among others elements of Seoul's population, the working class generally supports the Northern Koreans, while merchants are neutral and the intelligentsia continue to be pro-Southern. A former Seoul policeman reports that North Korean troops and police are rather inconspicuous in Seoul. Commercially, the city is nearly "dead"; stores are closed except for two department stores and some greengrocers. The streets, however, are crowded, especially with youths engaging in Communist demonstrations.”

R.H. Hillenkoeter, Director of Central Intelligence (1950-7-19). "The Korean Situation" CIA Memorandum. Archived from the original on 2022-07-23. - ↑ Kim Dong-Choon (2004). Forgotten war, forgotten massacres--the Korean War (1950-1953) as licensed mass killings. [PDF] Journal of Genocide Research.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 Korea: The Unknown War. TV Documentary Series. Episode 2: "An Arrogant Display of Strength." Thames Television, 1988. Aired on WGBH Boston, 1990. (URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aVCuku3Ldi0)

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 “On July 26, 1950, outside the central South Korean village of No Gun Ri, hundreds of civilians from nearby villages, ordered south by U.S. troops, were stopped by a dug-in battalion of the U.S. 7th Cavalry Regiment, and then were attacked without warning by U.S. warplanes. Survivors fled under a railroad overpass, where for the next three days they were fired on by 7th Cavalry troops. [...] in January 2001 the Army acknowledged the No Gun Ri killings but assigned no blame, calling it a “deeply regrettable accompaniment to a war.” [...] In 2006 it emerged that among incriminating documents omitted from the 2001 U.S. report was a declassified letter from the U.S. ambassador in South Korea, dated the day the No Gun Ri killings began, saying the Army had adopted a policy of firing on refugee groups approaching its lines.”

Youkyung Lee (2014-08-07). "S. Korean who forced US to admit massacre has died" Associated Press. Archived from the original. - ↑ Kim Dong choon (2010-03-01). "The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Korea: Uncovering the Hidden Korean War. The Other War: Korean War Massacres." The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus. Archived from the original on 2022-07-26. Retrieved 2022-07-26.

- ↑ Walter Karig; Malcolm W Cagle; Frank A Manson; et al (1952). Battle Report: The War in Korea (pp. 111-112). New York: Rinehart.

- ↑ Richard H. Kohn and Joseph P. Harahan (1988). Strategic Air Warfare: an interview with generals Curtis E. LeMay, Leon W. Johnson, David A. Burchinal, and Jack J. Catton (p. 88). Washington, D.C.: Office of Air Force History, United States Air Force. ISBN 0-912799-56-0

- ↑ Korea: The Unknown War. TV Documentary Series. Episode 2: "An Arrogant Display of Strength." Thames Television, 1988. Aired on WGBH Boston, 1990. (URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aVCuku3Ldi0)

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 35.2 Sang-Hun Choe, Charles J. Hanley and Martha Mendoza (1999-09-30). "U.S. Massacre of Civilians in Korean War Described" Washington Post. Archived from the original. Retrieved 2022-07-26.

- ↑ Cause of the 4.19 Revolution.

- ↑ "The Democratic Interlude". Library of Congress.

- ↑ K. J. Noh (2020-12-02). "South Korean Dictator Dies, Western Media Resurrects a Myth" Hampton Institute. Archived from the original on 2022-05-19. Retrieved 2022-06-02.

- ↑ "제6공화국 (Sixth Republic)". 두산백과 (Doopedia). Retrieved 2022-07-24.

- ↑ Hyonhee Shin (2018-06-11). "Vindication: Architects of South Korea's 'Sunshine' policy on North say it's paying off" Reuters.

- ↑ Hyonhee Shin (2021-12-31). "S.Korea's disgraced ex-president Park freed after nearly 5 years in prison" Reuters.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 Dr. William Selig (2022-02-26). "4th Think Tank 2022 Forum Features Former U.S. Secretary of Defense" Universal Peace Federation. Archived from the original on 2022-07-23. Retrieved 2022-07-23.

- ↑ "Co-Founder Dr. Hak Ja Han Moon". Think Tank 2022.

- ↑ “Sun Myung Moon was a Korean religious leader, businessman, and media mogul who had a net worth of $900 million at the time of his death. Sun Myung Moon was best known for founding the Unification movement and authoring its conservative theology of the "Divine Principle." [...] Some considered him a cult leader.”

"Sun Myung Moon Net Worth". Celebrity Net Worth. - ↑ “Moon saw himself as a messiah and created a church that became a worldwide movement and claims to have around 3 million members, including 100,000 in the United States. [...] He was jailed for five years by the North Korean government in 1948, but escaped in 1950 when his guards fled as United Nations troops advanced. He was an active anti-Communist throughout the cold war.”

Conal Urquhart (2012-09-03). "Sun Myung Moon, founder of the Moonies, dies in South Korea" The Guardian. - ↑ 46.0 46.1 46.2 Esper, Mark. 4th Think Tank 2022 Forum. "Hon. Mart[sic] Esper, 27th United States Secretary of Defense keynote address." Think Tank 2022. Uploaded April 13, 2022. URL:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DfKih9aabsk (NATO-related quote begins at 16:36)

- ↑ "Yoon to attend NATO summit, 1st time for S. Korean president" (2022-06-22). Kyodo News.

- ↑ "Korea to open diplomatic mission to NATO" (2022-06-22). Korea JoongAng Daily.

- ↑ "Solitary: Tough test of survival instinct" (1999-02-25). BBC News. Archived from the original.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 Kim Dong-won. Repatriation (2003). Documentary. URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1xu2mEvU29Q

- ↑ Photo by 김철수 (Kim Cheoulsu). 민중의소리 (Voice of the People). 인도적조치 비전향장기수 송환하라[포토] (Repatriate non-converted long-term prisoners for humanitarian measures [Photo]). 2020-09-08.

- ↑ "World's Longest Held Political Prisoner Released" (1995-11-15). Prison Legal News. Archived from the original.

- ↑ "북한, 비전향장기수 북송 21주년 맞아 생존 장기수들 조명 (North Korea celebrates 21st anniversary of repatriation of non-converted long-term prisoners to North Korea)" (2021-09-06). 파이낸셜 뉴스 (Financial News).

- ↑ Kang Jin-kyu (2016-08-07). "Spies who can't come in from the cold" Korea JoongAng Daily.

- ↑ Yoon, Cindy (2003-03-28), "Kim Dong Won's Film on North Korean Prisoners Held in South Korea", Asia Society. Archive link

- ↑ Meredith Shaw and Joseph Yi. (2022-03-15). "Will Yoon Suk-yeol Finally Reform South Korea’s National Security Law?" The Diplomat.

- ↑ Lashing out at “Hell Joseon”, young’uns drive ruling party’s election beatdown

- ↑ Young South Koreans call their country ‘hell’ and look for ways out by the Washington Post

- ↑ THE TRAIN IS CAPITALISM- SNOWPIERCER AND CLASS CONSCIOUNESS

- ↑ Parasite and Capitalism: What the Film Says About the Pursuit of Wealth

- ↑ Squid Game & The Rise Of Anti-Capitalist Entertainment

- ↑ “The Squid Game”: Anti-Capitalism and Netflix

- ↑ “Squid Game” Works Because Capitalism Is A Global Scourge

- ↑ Katrin Park (2021-10-5). "South Korea Is No Country for Young People" Foreign Policy.

- ↑ HALF A MILLION SOUTH KOREAN WORKERS WALK OFF JOBS IN GENERAL STRIKE on The Real News Network