Library:Free Software, Free Society: Difference between revisions

More languages

More actions

(Create empty stub article, so I can begin to transcribe this work on the visual editor. (ISBN: 978-0-9831592-0-9) Reason for inclusion: Includes criticisms and details about copyright and patent law related to ethics in the software space. Good as a historiographical piece to be used as a source in future articles that bring up the fringe of liberal-academic views on ethics in the modern era, along with vigilance.) |

(Transcription status: Pages 24/230) Tag: Visual edit |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

== Editor's Note == | |||

The waning days of the 20th century seemed like an Orwellian nightmare: laws preventing publication of scientific research on software; laws preventing sharing software; an overabundance of software patents preventing development; and enduser license agreements that strip the user of all freedoms—including ownership, privacy, sharing, and understanding how their software works. This collection of essays and speeches by Richard M. Stallman addresses many of these issues. Above all, Stallman discusses the philosophy underlying the free software movement. This movement combats the oppression of federal laws and evil end-user license agreements in hopes of spreading the idea of software freedom. | |||

With the force of hundreds of thousands of developers working to create GNU software and the GNU/Linux operating system, free software has secured a spot on the servers that control the Internet, and—as it moves into the desktop computer market—is a threat to Microsoft and other proprietary software companies. | |||

These essays cater to a wide audience; you do not need a computer science background to understand the philosophy and ideas herein. However, there is a “Note on Software,” to help the less technically inclined reader become familiar with some common computer science jargon and concepts, as well as footnotes throughout. | |||

Many of these essays have been updated and revised from their originally published version. Each essay carries permission to redistribute verbatim copies. | |||

The ordering of the essays is fairly arbitrary, in that there is no required order to read the essays in, for they were written independently of each other over a period of 18 years. The first section, “The GNU Project and Free Software,” is intended to familiarize you with the history and philosophy of free software and the GNU project. Furthermore, it provides a road map for developers, educators, and business people to pragmatically incorporate free software into society, business, and life. The second section, “Copyright, Copyleft, and Patents,” discusses the philosophical and political groundings of the copyright and patent system and how it has changed over the past couple of hundred years. Also, it discusses how the current laws and regulations for patents and copyrights are not in the best interest of the consumer and end user of software, music, movies, and other media. Instead, this section discusses how laws are geared towards helping business and government crush your freedoms. The third section, “Freedom, Society, and Software” continues the discussion of freedom and rights, and how they are being threatened by proprietary software, copyright law, globalization, “trusted computing,” and other socially harmful rules, regulations, and policies. One way that industry and government are attempting to persuade people to give up certain rights and freedoms is by using terminology that implies that sharing information, ideas, and software is bad; therefore, we have included an essay explaining certain words that are confusing and should probably be avoided. The fourth section, “The Licenses,” contains the GNU General Public License, the GNU Lesser General Public License, and the GNU Free Documentation License; the cornerstones of the GNU project. | |||

If you wish to purchase this book for yourself, for classroom use, or for distribution, please write to the Free Software Foundation (FSF) at sales@fsf.org or visit <nowiki>http://order.fsf.org/</nowiki>. If you wish to help further the cause of software freedom, please considering donating to the FSF by visiting <nowiki>http://donate.fsf.org</nowiki> (or write to donations@fsf.org for more details). You can also contact the FSF by phone at +1-617-542-5942. | |||

There are perhaps thousands of people who should be thanked for their contributions to the GNU Project; however, their names will never fit on any single list. Therefore, I wish to extend my thanks to all of those nameless hackers, as well as people who have helped promote, create, and spread free software around the world. | |||

For helping make this book possible, I would like to thank: | |||

Julie Sussman, P.P.A., for editing multiple copies at various stages of development, for writing the “Topic Guide,” and for giving her insights into everything from commas to the ordering of the chapters; | |||

Lisa (Opus) Goldstein and Bradley M. Kuhn for their help in organizing, proofreading, and generally making this collection possible; | |||

Claire H. Avitabile, Richard Buckman, Tom Chenelle, and (especially) Stephen Compall for their careful proofreading of the entire collection; | |||

Karl Berry, Bob Chassell, Michael Mounteney, and M. Ramakrishnan for their expertise in the helping to format and edit this collection in TEXinfo, (<nowiki>http://www.texinfo.org</nowiki>); | |||

Mats Bengtsson for his help in formatting the Free Software Song in Lilypond (<nowiki>http://www.gnu.org/software/lilypond/</nowiki>); | |||

Etienne Suvasa for the images that begin each section, and for all the art he has contributed to the Free Software Foundation over the years; | |||

and Melanie Flanagan and Jason Polan for making helpful suggestions for the everyday reader. A special thanks to Bob Tocchio, from Paul’s Transmission Repair, for his insight on automobile transmissions. | |||

Also, I wish to thank my mother and father, Wayne and Jo-Ann Gay, for teaching me that one should live by the ideals that one stands for, and for introducing me, my two brothers, and three sisters to the importance of sharing. | |||

Lastly and most importantly, I would like to extend my gratitude to Richard M. Stallman for the GNU philosophy, the wonderful software, and the literature that he has shared with the world. | |||

Joshua Gay | |||

josh@gnu.org | |||

== A Note on Software == | |||

This section is intended for people who have little or no knowledge of the technical aspects of computer science. It is not necessary to read this section to understand the essays and speeches presented in this book; however, it may be helpful to those readers not familar with some of the jargon that comes with programming and computer science. | |||

A computer ''programmer'' writes software, or computer programs. A program is more or less a recipe with ''commands'' to tell the computer what to do in order to carry out certain tasks. You are more than likely familiar with many different programs: your Web browser, your word processor, your email client, and the like. | |||

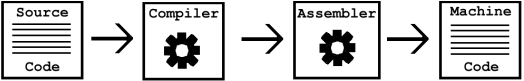

A program usually starts out as ''source code''. This higher-level set of commands is written in a ''programming language'' such as C or Java. After that, a tool known as a ''compiler'' translates this to a lower-level language known as ''assembly language''. Another tool known as an ''assembler'' breaks the assembly code down to the final stage of machine language—the lowest level—which the computer understands natively. | |||

[[File:Software Production Line.png|alt=An image showing the general outline of how software is made. Source code goes trough a compiler, then trough an assembler, and becomes computer-executable machine code.|thumb|Assembly line of computer code.]] | |||

For example, consider the “hello world” program, a common first program for people learning C, which (when compiled and executed) prints “Hello World!” on the screen. [1]<syntaxhighlight lang="c"> | |||

int main(){ | |||

printf("Hello World!"); | |||

return 0; | |||

} | |||

</syntaxhighlight>In the Java programming language the same program would be written like this:<syntaxhighlight lang="java"> | |||

public class hello { | |||

public static void main(String args[]) { | |||

System.out.println(’’Hello World!’’); | |||

} | |||

} | |||

</syntaxhighlight>However, in machine language, a small section of it may look similar to this:<syntaxhighlight> | |||

1100011110111010100101001001001010101110 | |||

0110101010011000001111001011010101111101 | |||

0100111111111110010110110000000010100100 | |||

0100100001100101011011000110110001101111 | |||

0010000001010111011011110111001001101100 | |||

0110010000100001010000100110111101101111 | |||

</syntaxhighlight>The above form of machine language is the most basic representation known as binary. All data in computers is made up of a series of 0-or-1 values, but a person would have much difficulty understanding the data. To make a simple change to the binary, one would have to have an intimate knowledge of how a particular computer interprets the machine language. This could be feasible for small programs like the above examples, but any interesting program would involve an exhausting effort to make simple changes. | |||

As an example, imagine that we wanted to make a change to our “Hello World” program written in C so that instead of printing “Hello World” in English it prints it in French. The change would be simple; here is the new program:<syntaxhighlight lang="c"> | |||

int main() { | |||

printf("Bonjour, monde!"); | |||

return 0; | |||

} | |||

</syntaxhighlight>It is safe to say that one can easily infer how to change the program written in the Java programming language in the same way. However, even many programmers would not know where to begin if they wanted to change the binary representation. When we say “source code,” we do not mean machine language that only computers can understand—we are speaking of higher-level languages such as C and Java. A few other popular programming languages are C++, Perl, and Python. Some are harder than others to understand and program in, but they are all much easier to work with compared to the intricate machine language they get turned into after the programs are compiled and assembled. | |||

Another important concept is understanding what an operating system is. An operating system is the software that handles input and output, memory allocation, and task scheduling. Generally one considers common or useful programs such as the Graphical User Interface (GUI) to be a part of the operating system. The GNU/Linux operating system contains a both GNU and non-GNU software, and a kernel called Linux. The kernel handles low-level tasks that applications depend upon such as input/output and task scheduling. The GNU software comprises much of the rest of the operating system, including GCC, a general-purpose compiler for many languages; GNU Emacs, an extensible text editor with many, many features; GNOME, the GNU desktop; GNU libc, a library that all programs other than the kernel must use in order to communicate with the kernel; and Bash, the GNU command interpreter that reads your command lines. Many of these programs were pioneered by Richard Stallman early on in the GNU Project and come with any modern GNU/Linux operating system. | |||

It is important to understand that even if you cannot change the source code for a given program, or directly use all these tools, it is relatively easy to find someone who can. Therefore, by having the source code to a program you are usually given the power to change, fix, customize, and learn about a program—this is a power that you do not have if you are not given the source code. Source code is one of the requirements that makes a piece of software free. The other requirements will be found along with the philosophy and ideas behind them in this collection. Enjoy! | |||

''Richard E. Buckman'' | |||

''Joshua Gay'' | |||

=== Section Footnotes === | |||

'''[1]''' In other programming languages, such as Scheme, the ''Hello World'' program is usually not your first program. In Scheme you often start with a program like this:<syntaxhighlight lang="scheme"> | |||

(define (factorial n) | |||

(if (= n 0) | |||

1 | |||

(* n (factorial (- n 1))))) | |||

</syntaxhighlight>This computes the factorial of a number; that is, running <code>(factorial 5)</code> would output 120, which is computed by doing 5 * 4 * 3 * 2 * 1 * 1. | |||

== Topic Guide == | |||

Since the essays and speeches in this book were addressed to different audiences at different times, there is a considerable amount of overlap, with some issues being discussed in more than one place. Because of this, and because we did not have the opportunity to make an index for this book, it could be hard to go back to something you read about unless its location is obvious from a chapter title. | |||

We hope that this short guide, though sketchy and incomplete (it does not cover all topics or all discussions of a given topic), will help you find some of the ideas and explanations you are interested in. | |||

''–Julie Sussman, P.P.A.'' | |||

'''Overview''' | |||

Chapter 1 gives an overview of just about all the software-related topics in this book. Chapter 20 is also an overview. | |||

For the non-software topics, see Privacy and Personal Freedom, Intellectual Property, and Copyright, below. | |||

'''GNU Project''' | |||

For the history of the GNU project, see Chapters 1 and 20 | |||

For a delightful explanation of the origin and pronunciation of the recursive acronym GNU (GNU’s Not Unix, pronounced guh-NEW), see Chapter 20. | |||

The “manifesto” that launched the GNU Project is included here as Chapter 2. See also the Linux, GNU/Linux topic below. | |||

'''Free Software Foundation''' | |||

You can read about the history and function of the Free Software Foundation in Chapters 1 and 20, and under “Funding Free Software” in Chapter 18. | |||

'''Free software''' | |||

We will not attempt to direct you to all discussions of free software in this book, since every chapter ''except'' 11, 12, 13, 16, 17, and 19 deals with free software. For a history of free software—from free software to proprietary software and back again—see Chapter 1. | |||

Free Software is defined, and the definition discussed, in Chapter 3. The definition is repeated in several other chapters. | |||

For a discussion of the ambiguity of the word “free” and why we still use it to mean “free” as in “free speech,” not as in “free beer,” see “Free as in Freedom” in Chapter 1 and “Ambiguity” in chapter 6. | |||

See also Source Code, Open Source, and Copyleft, below. ''Free software'' is translated into 21 languages in Chapter 21. | |||

'''Source Code, Source''' | |||

''Source code'' is mentioned throughout the discussions of free software. If you’re not sure what that is, read “A Note on Software.” | |||

'''Linux, GNU/Linux''' | |||

For the origin of Linux, and the distinction between Linux (the operating-system kernel) and GNU/Linux (a full operating system), see the short mention under “Linux and GNU/Linux” in Chapter 1 and the full story in Chapter 20/ | |||

For reasons to say GNU/Linux when referring to that operating system rather than abbreviating it to Linux see Chapters 5 and 20. | |||

'''Privacy and Personal Freedom''' | |||

For some warnings about the loss of personal freedom, privacy, and access to written material that we have long taken for granted, see Chapters 11, 13, and 17. All of these are geared to a general audience. | |||

'''Open Source''' | |||

For the difference between the Open Source movement and the Free Software movement, see Chapter 6. This is also discussed in Chapter 1 (under “Open Source”) and Chapter 20. | |||

'''Intellectual Property''' | |||

For an explanation of why the term “intellectual property” is both misleading and a barrier to addressing so-called “intellectual property” issues, see Chapter 21 and the beginning of Chapter 16. | |||

For particular types of “intellectual property” see the Copyright and Patents topics, below. | |||

'''Copyright''' | |||

Note: Most of these copyright references are ''not'' about software. | |||

For the history, purpose, implementation, and effects of copyright, as well as recommendations for copyright policy, see Chapters 12 and 19. Topics critical in our digital age, such as e-books and the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA), are addressed here. | |||

For the difference between patents and copyrights, see Chapter 16. | |||

For the use of copyright in promoting free software and free documentation, see Copyleft, just below. | |||

'''Copyleft''' | |||

For an explanation of copyleft and how it uses the copyright system to promote free software, see Chapter 1 (under “Copyleft and the GNU GPL”), Chapter 14, and Chapter 20. See also Licenses, below. | |||

For an argument that copyleft is practical and effective as well as idealistic, see Chapter 15. | |||

Chapter 9 argues for free manuals to accompany free software. | |||

'''Licenses''' | |||

The GNU licenses, which can be used to copyleft software or manuals, are introduced in Chapter 14 and given in full in Section Four. | |||

'''Patents''' | |||

See Chapter 16 for the difference between patents and copyrights and for arguments against patenting software and why it is different from other patentable things. Software-patent policy in other countries is also discussed. | |||

'''Hacker''' versus '''Cracker''' | |||

For the proper use of these terms see the beginning of Chapter 1. | |||

== Introduction == | |||

Every generation has its philosopher—a writer or an artist who captures the imagination of a time. Sometimes these philosophers are recognized as such; often it takes generations before the connection is made real. But recognized or not, a time gets marked by the people who speak its ideals, whether in the whisper of a poem, or the blast of a political movement. | |||

Our generation has a philosopher. He is not an artist, or a professional writer. He is a programmer. Richard Stallman began his work in the labs of MIT, as a programmer and architect building operating system software. He has built his career on a stage of public life, as a programmer and an architect founding a movement for freedom in a world increasingly defined by “code.” | |||

“Code” is the technology that makes computers run. Whether inscribed in software or burned in hardware, it is the collection of instructions, first written in words, that directs the functionality of machines. These machines—computers— increasingly define and control our life. They determine how phones connect, and what runs on TV. They decide whether video can be streamed across a broadband link to a computer. They control what a computer reports back to its manufacturer. These machines run us. Code runs these machines. | |||

What control should we have over this code? What understanding? What freedom should there be to match the control it enables? What power? | |||

These questions have been the challenge of Stallman’s life. Through his works and his words, he has pushed us to see the importance of keeping code “free.” Not free in the sense that code writers don’t get paid, but free in the sense that the control coders build be transparent to all, and that anyone have the right to take that control, and modify it as he or she sees fit. This is “free software”; “free software” is one answer to a world built in code. | |||

“Free.” Stallman laments the ambiguity in his own term. There’s nothing to lament. Puzzles force people to think, and this term “free” does this puzzling work quite well. To modern American ears, “free software” sounds utopian, impossible. Nothing, not even lunch, is free. How could the most important words running the most critical machines running the world be “free.” How could a sane society aspire to such an ideal? | |||

Yet the odd clink of the word “free” is a function of us, not of the term. “Free” has different senses, only one of which refers to “price.” A much more fundamental sense of “free” is the “free,” Stallman says, in the term “free speech,” or perhaps better in the term “free labor.” Not free as in costless, but free as in limited in its control by others. Free software is control that is transparent, and open to change, just as free laws, or the laws of a “free society,” are free when they make their control knowable, and open to change. The aim of Stallman’s “free software movement” is to make as much code as it can transparent, and subject to change, by rendering it “free.” | |||

The mechanism of this rendering is an extraordinarily clever device called “copyleft” implemented through a license called GPL. Using the power of copyright law, “free software” not only assures that it remains open, and subject to change, but that other software that takes and uses “free software” (and that technically counts as a “derivative work”) must also itself be free. If you use and adapt a free software program, and then release that adapted version to the public, the released version must be as free as the version it was adapted from. It must, or the law of copyright will be violated. | |||

“Free software,” like free societies, has its enemies. Microsoft has waged a war against the GPL, warning whoever will listen that the GPL is a “dangerous” license. The dangers it names, however, are largely illusory. Others object to the “coercion” in GPL’s insistence that modified versions are also free. But a condition is not coercion. If it is not coercion for Microsoft to refuse to permit users to distribute modified versions of its product Office without paying it (presumably) millions, then it is not coercion when the GPL insists that modified versions of free software be free too. | |||

And then there are those who call Stallman’s message too extreme. But extreme it is not. Indeed, in an obvious sense, Stallman’s work is a simple translation of the freedoms that our tradition crafted in the world before code. “Free software” would assure that the world governed by code is as “free” as our tradition that built the world before code. | |||

For example: A “free society” is regulated by law. But there are limits that any free society places on this regulation through law: No society that kept its laws secret could ever be called free. No government that hid its regulations from the regulated could ever stand in our tradition. Law controls. But it does so justly only when visibly. And law is visible only when its terms are knowable and controllable by those it regulates, or by the agents of those it regulates (lawyers, legislatures). | |||

This condition on law extends beyond the work of a legislature. Think about the practice of law in American courts. Lawyers are hired by their clients to advance their clients’ interests. Sometimes that interest is advanced through litigation. In the course of this litigation, lawyers write briefs. These briefs in turn affect opinions written by judges. These opinions decide who wins a particular case, or whether a certain law can stand consistently with a constitution. | |||

All the material in this process is free in the sense that Stallman means. Legal briefs are open and free for others to use. The arguments are transparent (which is different from saying they are good) and the reasoning can be taken without the permission of the original lawyers. The opinions they produce can be quoted in later briefs. They can be copied and integrated into another brief or opinion. The “source code” for American law is by design, and by principle, open and free for anyone to take. And take lawyers do—for it is a measure of a great brief that it achieves its creativity through the reuse of what happened before. The source is free; creativity and an economy is built upon it. | |||

This economy of free code (and here I mean free legal code) doesn’t starve lawyers. Law firms have enough incentive to produce great briefs even though the stuff they build can be taken and copied by anyone else. The lawyer is a craftsman; his or her product is public. Yet the crafting is not charity. Lawyers get paid; the public doesn’t demand such work without price. Instead this economy flourishes, with later work added to the earlier. | |||

We could imagine a legal practice that was different—briefs and arguments that were kept secret; rulings that announced a result but not the reasoning. Laws that were kept by the police but published to no one else. Regulation that operated without explaining its rule. | |||

We could imagine this society, but we could not imagine calling it “free.” Whether or not the incentives in such a society would be better or more efficiently allocated, such a society could not be known as free. The ideals of freedom, of life within a free society, demand more than efficient application. Instead, openness and transparency are the constraints within which a legal system gets built, not options to be added if convenient to the leaders. Life governed by software code should be no less. | |||

Code writing is not litigation. It is better, richer, more productive. But the law is an obvious instance of how creativity and incentives do not depend upon perfect control over the products created. Like jazz, or novels, or architecture, the law gets built upon the work that went before. This adding and changing is what creativity always is. And a free society is one that assures that its most important resources remain free in just this sense. | |||

For the first time, this book collects the writing and lectures of Richard Stallman in a manner that will make their subtlety and power clear. The essays span a wide range, from copyright to the history of the free software movement. They include many arguments not well known, and among these, an especially insightful account of the changed circumstances that render copyright in the digital world suspect. They will serve as a resource for those who seek to understand the thought of this most powerful man—powerful in his ideas, his passion, and his integrity, even if powerless in every other way. They will inspire others who would take these ideas, and build upon them. | |||

I don’t know Stallman well. I know him well enough to know he is a hard man to like. He is driven, often impatient. His anger can flare at friend as easily as foe. He is uncompromising and persistent; patient in both. | |||

Yet when our world finally comes to understand the power and danger of code— when it finally sees that code, like laws, or like government, must be transparent to be free—then we will look back at this uncompromising and persistent programmer and recognize the vision he has fought to make real: the vision of a world where freedom and knowledge survives the compiler. And we will come to see that no man, through his deeds or words, has done as much to make possible the freedom that this next society could have. | |||

We have not earned that freedom yet. We may well fail in securing it. But whether we succeed or fail, in these essays is a picture of what that freedom could be. And in the life that produced these words and works, there is inspiration for anyone who would, like Stallman, fight to create this freedom. | |||

''Lawrence Lessig'' | |||

''Professor of Law, Stanford Law School.'' | |||

== Section One: The GNU Project and Free Software == | |||

[[File:Screenshot from 2023-01-01 13-23-47.png|alt=A satirical image, a knight riding an angry Gnu (the animal).|thumb|Satirical image: A knight riding a Gnu.]] | |||

=== The First Software-Sharing Community === | |||

When I started working at the MIT Artificial Intelligence Lab in 1971, I became part of a software-sharing community that had existed for many years. Sharing of software was not limited to our particular community; it is as old as computers, just as sharing of recipes is as old as cooking. But we did it more than most. | |||

The AI Lab used a timesharing operating system called ITS (the Incompatible Timesharing System) that the lab’s staff hackers had designed and written in assembler language for the Digital PDP-10, one of the large computers of the era. As a member of this community, an AI lab staff system hacker, my job was to improve this system. | |||

We did not call our software “free software,” because that term did not yet exist; but that is what it was. Whenever people from another university or a company wanted to port and use a program, we gladly let them. If you saw someone using an unfamiliar and interesting program, you could always ask to see the source code, so that you could read it, change it, or cannibalize parts of it to make a new program. | |||

The use of “hacker” to mean “security breaker” is a confusion on the part of the mass media. We hackers refuse to recognize that meaning, and continue using the word to mean, “Someone who loves to program and enjoys being clever about it.”[1] | |||

=== The Collapse of the Community === | |||

The situation changed drastically in the early 1980s, with the collapse of the AI Lab hacker community followed by the discontinuation of the PDP-10 computer. | |||

In 1981, the spin-off company Symbolics hired away nearly all of the hackers from the AI Lab, and the depopulated community was unable to maintain itself. (The book Hackers, by Steven Levy, describes these events, as well as giving a clear picture of this community in its prime.) When the AI Lab bought a new PDP10 in 1982, its administrators decided to use Digital’s non-free timesharing system instead of ITS on the new machine. | |||

Not long afterwards, Digital discontinued the PDP-10 series. Its architecture, elegant and powerful in the 60s, could not extend naturally to the larger address spaces that were becoming feasible in the 80s. This meant that nearly all of the programs composing ITS were obsolete. That put the last nail in the coffin of ITS; 15 years of work went up in smoke. | |||

The modern computers of the era, such as the VAX or the 68020, had their own operating systems, but none of them were free software: you had to sign a nondisclosure agreement even to get an executable copy. | |||

This meant that the first step in using a computer was to promise not to help your neighbor. A cooperating community was forbidden. The rule made by the owners of proprietary software was, “If you share with your neighbor, you are a pirate. If you want any changes, beg us to make them.” | |||

The idea that the proprietary-software social system—the system that says you are not allowed to share or change software—is antisocial, that it is unethical, that it is simply wrong, may come as a surprise to some readers. But what else could we say about a system based on dividing the public and keeping users helpless? Readers who find the idea surprising may have taken this proprietary-software social system as given, or judged it on the terms suggested by proprietarysoftware businesses. Software publishers have worked long and hard to convince people that there is only one way to look at the issue. | |||

When software publishers talk about “enforcing” their “rights” or “stopping piracy,” what they actually “say” is secondary. The real message of these statements is in the unstated assumptions they take for granted; the public is supposed to accept them uncritically. So let’s examine them. | |||

One assumption is that software companies have an unquestionable natural right to own software and thus have power over all its users. (If this were a natural right, then no matter how much harm it does to the public, we could not object.) Interestingly, the U.S. Constitution and legal tradition reject this view; copyright is not a natural right, but an artificial government-imposed monopoly that limits the users’ natural right to copy. | |||

Another unstated assumption is that the only important thing about software is what jobs it allows you to do—that we computer users should not care what kind of society we are allowed to have. | |||

Revision as of 19:47, 1 January 2023

Editor's Note

The waning days of the 20th century seemed like an Orwellian nightmare: laws preventing publication of scientific research on software; laws preventing sharing software; an overabundance of software patents preventing development; and enduser license agreements that strip the user of all freedoms—including ownership, privacy, sharing, and understanding how their software works. This collection of essays and speeches by Richard M. Stallman addresses many of these issues. Above all, Stallman discusses the philosophy underlying the free software movement. This movement combats the oppression of federal laws and evil end-user license agreements in hopes of spreading the idea of software freedom.

With the force of hundreds of thousands of developers working to create GNU software and the GNU/Linux operating system, free software has secured a spot on the servers that control the Internet, and—as it moves into the desktop computer market—is a threat to Microsoft and other proprietary software companies.

These essays cater to a wide audience; you do not need a computer science background to understand the philosophy and ideas herein. However, there is a “Note on Software,” to help the less technically inclined reader become familiar with some common computer science jargon and concepts, as well as footnotes throughout.

Many of these essays have been updated and revised from their originally published version. Each essay carries permission to redistribute verbatim copies.

The ordering of the essays is fairly arbitrary, in that there is no required order to read the essays in, for they were written independently of each other over a period of 18 years. The first section, “The GNU Project and Free Software,” is intended to familiarize you with the history and philosophy of free software and the GNU project. Furthermore, it provides a road map for developers, educators, and business people to pragmatically incorporate free software into society, business, and life. The second section, “Copyright, Copyleft, and Patents,” discusses the philosophical and political groundings of the copyright and patent system and how it has changed over the past couple of hundred years. Also, it discusses how the current laws and regulations for patents and copyrights are not in the best interest of the consumer and end user of software, music, movies, and other media. Instead, this section discusses how laws are geared towards helping business and government crush your freedoms. The third section, “Freedom, Society, and Software” continues the discussion of freedom and rights, and how they are being threatened by proprietary software, copyright law, globalization, “trusted computing,” and other socially harmful rules, regulations, and policies. One way that industry and government are attempting to persuade people to give up certain rights and freedoms is by using terminology that implies that sharing information, ideas, and software is bad; therefore, we have included an essay explaining certain words that are confusing and should probably be avoided. The fourth section, “The Licenses,” contains the GNU General Public License, the GNU Lesser General Public License, and the GNU Free Documentation License; the cornerstones of the GNU project.

If you wish to purchase this book for yourself, for classroom use, or for distribution, please write to the Free Software Foundation (FSF) at sales@fsf.org or visit http://order.fsf.org/. If you wish to help further the cause of software freedom, please considering donating to the FSF by visiting http://donate.fsf.org (or write to donations@fsf.org for more details). You can also contact the FSF by phone at +1-617-542-5942.

There are perhaps thousands of people who should be thanked for their contributions to the GNU Project; however, their names will never fit on any single list. Therefore, I wish to extend my thanks to all of those nameless hackers, as well as people who have helped promote, create, and spread free software around the world.

For helping make this book possible, I would like to thank:

Julie Sussman, P.P.A., for editing multiple copies at various stages of development, for writing the “Topic Guide,” and for giving her insights into everything from commas to the ordering of the chapters;

Lisa (Opus) Goldstein and Bradley M. Kuhn for their help in organizing, proofreading, and generally making this collection possible;

Claire H. Avitabile, Richard Buckman, Tom Chenelle, and (especially) Stephen Compall for their careful proofreading of the entire collection;

Karl Berry, Bob Chassell, Michael Mounteney, and M. Ramakrishnan for their expertise in the helping to format and edit this collection in TEXinfo, (http://www.texinfo.org);

Mats Bengtsson for his help in formatting the Free Software Song in Lilypond (http://www.gnu.org/software/lilypond/);

Etienne Suvasa for the images that begin each section, and for all the art he has contributed to the Free Software Foundation over the years;

and Melanie Flanagan and Jason Polan for making helpful suggestions for the everyday reader. A special thanks to Bob Tocchio, from Paul’s Transmission Repair, for his insight on automobile transmissions.

Also, I wish to thank my mother and father, Wayne and Jo-Ann Gay, for teaching me that one should live by the ideals that one stands for, and for introducing me, my two brothers, and three sisters to the importance of sharing.

Lastly and most importantly, I would like to extend my gratitude to Richard M. Stallman for the GNU philosophy, the wonderful software, and the literature that he has shared with the world.

Joshua Gay

josh@gnu.org

A Note on Software

This section is intended for people who have little or no knowledge of the technical aspects of computer science. It is not necessary to read this section to understand the essays and speeches presented in this book; however, it may be helpful to those readers not familar with some of the jargon that comes with programming and computer science.

A computer programmer writes software, or computer programs. A program is more or less a recipe with commands to tell the computer what to do in order to carry out certain tasks. You are more than likely familiar with many different programs: your Web browser, your word processor, your email client, and the like.

A program usually starts out as source code. This higher-level set of commands is written in a programming language such as C or Java. After that, a tool known as a compiler translates this to a lower-level language known as assembly language. Another tool known as an assembler breaks the assembly code down to the final stage of machine language—the lowest level—which the computer understands natively.

For example, consider the “hello world” program, a common first program for people learning C, which (when compiled and executed) prints “Hello World!” on the screen. [1]

int main(){

printf("Hello World!");

return 0;

}

In the Java programming language the same program would be written like this:

public class hello {

public static void main(String args[]) {

System.out.println(’’Hello World!’’);

}

}

However, in machine language, a small section of it may look similar to this:

1100011110111010100101001001001010101110

0110101010011000001111001011010101111101

0100111111111110010110110000000010100100

0100100001100101011011000110110001101111

0010000001010111011011110111001001101100

0110010000100001010000100110111101101111The above form of machine language is the most basic representation known as binary. All data in computers is made up of a series of 0-or-1 values, but a person would have much difficulty understanding the data. To make a simple change to the binary, one would have to have an intimate knowledge of how a particular computer interprets the machine language. This could be feasible for small programs like the above examples, but any interesting program would involve an exhausting effort to make simple changes. As an example, imagine that we wanted to make a change to our “Hello World” program written in C so that instead of printing “Hello World” in English it prints it in French. The change would be simple; here is the new program:

int main() {

printf("Bonjour, monde!");

return 0;

}

It is safe to say that one can easily infer how to change the program written in the Java programming language in the same way. However, even many programmers would not know where to begin if they wanted to change the binary representation. When we say “source code,” we do not mean machine language that only computers can understand—we are speaking of higher-level languages such as C and Java. A few other popular programming languages are C++, Perl, and Python. Some are harder than others to understand and program in, but they are all much easier to work with compared to the intricate machine language they get turned into after the programs are compiled and assembled.

Another important concept is understanding what an operating system is. An operating system is the software that handles input and output, memory allocation, and task scheduling. Generally one considers common or useful programs such as the Graphical User Interface (GUI) to be a part of the operating system. The GNU/Linux operating system contains a both GNU and non-GNU software, and a kernel called Linux. The kernel handles low-level tasks that applications depend upon such as input/output and task scheduling. The GNU software comprises much of the rest of the operating system, including GCC, a general-purpose compiler for many languages; GNU Emacs, an extensible text editor with many, many features; GNOME, the GNU desktop; GNU libc, a library that all programs other than the kernel must use in order to communicate with the kernel; and Bash, the GNU command interpreter that reads your command lines. Many of these programs were pioneered by Richard Stallman early on in the GNU Project and come with any modern GNU/Linux operating system.

It is important to understand that even if you cannot change the source code for a given program, or directly use all these tools, it is relatively easy to find someone who can. Therefore, by having the source code to a program you are usually given the power to change, fix, customize, and learn about a program—this is a power that you do not have if you are not given the source code. Source code is one of the requirements that makes a piece of software free. The other requirements will be found along with the philosophy and ideas behind them in this collection. Enjoy!

Richard E. Buckman

Joshua Gay

Section Footnotes

[1] In other programming languages, such as Scheme, the Hello World program is usually not your first program. In Scheme you often start with a program like this:

(define (factorial n)

(if (= n 0)

1

(* n (factorial (- n 1)))))

This computes the factorial of a number; that is, running (factorial 5) would output 120, which is computed by doing 5 * 4 * 3 * 2 * 1 * 1.

Topic Guide

Since the essays and speeches in this book were addressed to different audiences at different times, there is a considerable amount of overlap, with some issues being discussed in more than one place. Because of this, and because we did not have the opportunity to make an index for this book, it could be hard to go back to something you read about unless its location is obvious from a chapter title.

We hope that this short guide, though sketchy and incomplete (it does not cover all topics or all discussions of a given topic), will help you find some of the ideas and explanations you are interested in.

–Julie Sussman, P.P.A.

Overview

Chapter 1 gives an overview of just about all the software-related topics in this book. Chapter 20 is also an overview.

For the non-software topics, see Privacy and Personal Freedom, Intellectual Property, and Copyright, below.

GNU Project

For the history of the GNU project, see Chapters 1 and 20

For a delightful explanation of the origin and pronunciation of the recursive acronym GNU (GNU’s Not Unix, pronounced guh-NEW), see Chapter 20.

The “manifesto” that launched the GNU Project is included here as Chapter 2. See also the Linux, GNU/Linux topic below.

Free Software Foundation

You can read about the history and function of the Free Software Foundation in Chapters 1 and 20, and under “Funding Free Software” in Chapter 18.

Free software

We will not attempt to direct you to all discussions of free software in this book, since every chapter except 11, 12, 13, 16, 17, and 19 deals with free software. For a history of free software—from free software to proprietary software and back again—see Chapter 1.

Free Software is defined, and the definition discussed, in Chapter 3. The definition is repeated in several other chapters.

For a discussion of the ambiguity of the word “free” and why we still use it to mean “free” as in “free speech,” not as in “free beer,” see “Free as in Freedom” in Chapter 1 and “Ambiguity” in chapter 6.

See also Source Code, Open Source, and Copyleft, below. Free software is translated into 21 languages in Chapter 21.

Source Code, Source

Source code is mentioned throughout the discussions of free software. If you’re not sure what that is, read “A Note on Software.”

Linux, GNU/Linux

For the origin of Linux, and the distinction between Linux (the operating-system kernel) and GNU/Linux (a full operating system), see the short mention under “Linux and GNU/Linux” in Chapter 1 and the full story in Chapter 20/

For reasons to say GNU/Linux when referring to that operating system rather than abbreviating it to Linux see Chapters 5 and 20.

Privacy and Personal Freedom

For some warnings about the loss of personal freedom, privacy, and access to written material that we have long taken for granted, see Chapters 11, 13, and 17. All of these are geared to a general audience.

Open Source

For the difference between the Open Source movement and the Free Software movement, see Chapter 6. This is also discussed in Chapter 1 (under “Open Source”) and Chapter 20.

Intellectual Property

For an explanation of why the term “intellectual property” is both misleading and a barrier to addressing so-called “intellectual property” issues, see Chapter 21 and the beginning of Chapter 16.

For particular types of “intellectual property” see the Copyright and Patents topics, below.

Copyright

Note: Most of these copyright references are not about software.

For the history, purpose, implementation, and effects of copyright, as well as recommendations for copyright policy, see Chapters 12 and 19. Topics critical in our digital age, such as e-books and the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA), are addressed here.

For the difference between patents and copyrights, see Chapter 16.

For the use of copyright in promoting free software and free documentation, see Copyleft, just below.

Copyleft

For an explanation of copyleft and how it uses the copyright system to promote free software, see Chapter 1 (under “Copyleft and the GNU GPL”), Chapter 14, and Chapter 20. See also Licenses, below.

For an argument that copyleft is practical and effective as well as idealistic, see Chapter 15.

Chapter 9 argues for free manuals to accompany free software.

Licenses

The GNU licenses, which can be used to copyleft software or manuals, are introduced in Chapter 14 and given in full in Section Four.

Patents

See Chapter 16 for the difference between patents and copyrights and for arguments against patenting software and why it is different from other patentable things. Software-patent policy in other countries is also discussed.

Hacker versus Cracker

For the proper use of these terms see the beginning of Chapter 1.

Introduction

Every generation has its philosopher—a writer or an artist who captures the imagination of a time. Sometimes these philosophers are recognized as such; often it takes generations before the connection is made real. But recognized or not, a time gets marked by the people who speak its ideals, whether in the whisper of a poem, or the blast of a political movement.

Our generation has a philosopher. He is not an artist, or a professional writer. He is a programmer. Richard Stallman began his work in the labs of MIT, as a programmer and architect building operating system software. He has built his career on a stage of public life, as a programmer and an architect founding a movement for freedom in a world increasingly defined by “code.”

“Code” is the technology that makes computers run. Whether inscribed in software or burned in hardware, it is the collection of instructions, first written in words, that directs the functionality of machines. These machines—computers— increasingly define and control our life. They determine how phones connect, and what runs on TV. They decide whether video can be streamed across a broadband link to a computer. They control what a computer reports back to its manufacturer. These machines run us. Code runs these machines.

What control should we have over this code? What understanding? What freedom should there be to match the control it enables? What power?

These questions have been the challenge of Stallman’s life. Through his works and his words, he has pushed us to see the importance of keeping code “free.” Not free in the sense that code writers don’t get paid, but free in the sense that the control coders build be transparent to all, and that anyone have the right to take that control, and modify it as he or she sees fit. This is “free software”; “free software” is one answer to a world built in code.

“Free.” Stallman laments the ambiguity in his own term. There’s nothing to lament. Puzzles force people to think, and this term “free” does this puzzling work quite well. To modern American ears, “free software” sounds utopian, impossible. Nothing, not even lunch, is free. How could the most important words running the most critical machines running the world be “free.” How could a sane society aspire to such an ideal?

Yet the odd clink of the word “free” is a function of us, not of the term. “Free” has different senses, only one of which refers to “price.” A much more fundamental sense of “free” is the “free,” Stallman says, in the term “free speech,” or perhaps better in the term “free labor.” Not free as in costless, but free as in limited in its control by others. Free software is control that is transparent, and open to change, just as free laws, or the laws of a “free society,” are free when they make their control knowable, and open to change. The aim of Stallman’s “free software movement” is to make as much code as it can transparent, and subject to change, by rendering it “free.”

The mechanism of this rendering is an extraordinarily clever device called “copyleft” implemented through a license called GPL. Using the power of copyright law, “free software” not only assures that it remains open, and subject to change, but that other software that takes and uses “free software” (and that technically counts as a “derivative work”) must also itself be free. If you use and adapt a free software program, and then release that adapted version to the public, the released version must be as free as the version it was adapted from. It must, or the law of copyright will be violated.

“Free software,” like free societies, has its enemies. Microsoft has waged a war against the GPL, warning whoever will listen that the GPL is a “dangerous” license. The dangers it names, however, are largely illusory. Others object to the “coercion” in GPL’s insistence that modified versions are also free. But a condition is not coercion. If it is not coercion for Microsoft to refuse to permit users to distribute modified versions of its product Office without paying it (presumably) millions, then it is not coercion when the GPL insists that modified versions of free software be free too.

And then there are those who call Stallman’s message too extreme. But extreme it is not. Indeed, in an obvious sense, Stallman’s work is a simple translation of the freedoms that our tradition crafted in the world before code. “Free software” would assure that the world governed by code is as “free” as our tradition that built the world before code.

For example: A “free society” is regulated by law. But there are limits that any free society places on this regulation through law: No society that kept its laws secret could ever be called free. No government that hid its regulations from the regulated could ever stand in our tradition. Law controls. But it does so justly only when visibly. And law is visible only when its terms are knowable and controllable by those it regulates, or by the agents of those it regulates (lawyers, legislatures).

This condition on law extends beyond the work of a legislature. Think about the practice of law in American courts. Lawyers are hired by their clients to advance their clients’ interests. Sometimes that interest is advanced through litigation. In the course of this litigation, lawyers write briefs. These briefs in turn affect opinions written by judges. These opinions decide who wins a particular case, or whether a certain law can stand consistently with a constitution.

All the material in this process is free in the sense that Stallman means. Legal briefs are open and free for others to use. The arguments are transparent (which is different from saying they are good) and the reasoning can be taken without the permission of the original lawyers. The opinions they produce can be quoted in later briefs. They can be copied and integrated into another brief or opinion. The “source code” for American law is by design, and by principle, open and free for anyone to take. And take lawyers do—for it is a measure of a great brief that it achieves its creativity through the reuse of what happened before. The source is free; creativity and an economy is built upon it.

This economy of free code (and here I mean free legal code) doesn’t starve lawyers. Law firms have enough incentive to produce great briefs even though the stuff they build can be taken and copied by anyone else. The lawyer is a craftsman; his or her product is public. Yet the crafting is not charity. Lawyers get paid; the public doesn’t demand such work without price. Instead this economy flourishes, with later work added to the earlier.

We could imagine a legal practice that was different—briefs and arguments that were kept secret; rulings that announced a result but not the reasoning. Laws that were kept by the police but published to no one else. Regulation that operated without explaining its rule.

We could imagine this society, but we could not imagine calling it “free.” Whether or not the incentives in such a society would be better or more efficiently allocated, such a society could not be known as free. The ideals of freedom, of life within a free society, demand more than efficient application. Instead, openness and transparency are the constraints within which a legal system gets built, not options to be added if convenient to the leaders. Life governed by software code should be no less.

Code writing is not litigation. It is better, richer, more productive. But the law is an obvious instance of how creativity and incentives do not depend upon perfect control over the products created. Like jazz, or novels, or architecture, the law gets built upon the work that went before. This adding and changing is what creativity always is. And a free society is one that assures that its most important resources remain free in just this sense.

For the first time, this book collects the writing and lectures of Richard Stallman in a manner that will make their subtlety and power clear. The essays span a wide range, from copyright to the history of the free software movement. They include many arguments not well known, and among these, an especially insightful account of the changed circumstances that render copyright in the digital world suspect. They will serve as a resource for those who seek to understand the thought of this most powerful man—powerful in his ideas, his passion, and his integrity, even if powerless in every other way. They will inspire others who would take these ideas, and build upon them.

I don’t know Stallman well. I know him well enough to know he is a hard man to like. He is driven, often impatient. His anger can flare at friend as easily as foe. He is uncompromising and persistent; patient in both.

Yet when our world finally comes to understand the power and danger of code— when it finally sees that code, like laws, or like government, must be transparent to be free—then we will look back at this uncompromising and persistent programmer and recognize the vision he has fought to make real: the vision of a world where freedom and knowledge survives the compiler. And we will come to see that no man, through his deeds or words, has done as much to make possible the freedom that this next society could have.

We have not earned that freedom yet. We may well fail in securing it. But whether we succeed or fail, in these essays is a picture of what that freedom could be. And in the life that produced these words and works, there is inspiration for anyone who would, like Stallman, fight to create this freedom.

Lawrence Lessig

Professor of Law, Stanford Law School.

Section One: The GNU Project and Free Software

The First Software-Sharing Community

When I started working at the MIT Artificial Intelligence Lab in 1971, I became part of a software-sharing community that had existed for many years. Sharing of software was not limited to our particular community; it is as old as computers, just as sharing of recipes is as old as cooking. But we did it more than most.

The AI Lab used a timesharing operating system called ITS (the Incompatible Timesharing System) that the lab’s staff hackers had designed and written in assembler language for the Digital PDP-10, one of the large computers of the era. As a member of this community, an AI lab staff system hacker, my job was to improve this system.

We did not call our software “free software,” because that term did not yet exist; but that is what it was. Whenever people from another university or a company wanted to port and use a program, we gladly let them. If you saw someone using an unfamiliar and interesting program, you could always ask to see the source code, so that you could read it, change it, or cannibalize parts of it to make a new program.

The use of “hacker” to mean “security breaker” is a confusion on the part of the mass media. We hackers refuse to recognize that meaning, and continue using the word to mean, “Someone who loves to program and enjoys being clever about it.”[1]

The Collapse of the Community

The situation changed drastically in the early 1980s, with the collapse of the AI Lab hacker community followed by the discontinuation of the PDP-10 computer.

In 1981, the spin-off company Symbolics hired away nearly all of the hackers from the AI Lab, and the depopulated community was unable to maintain itself. (The book Hackers, by Steven Levy, describes these events, as well as giving a clear picture of this community in its prime.) When the AI Lab bought a new PDP10 in 1982, its administrators decided to use Digital’s non-free timesharing system instead of ITS on the new machine.

Not long afterwards, Digital discontinued the PDP-10 series. Its architecture, elegant and powerful in the 60s, could not extend naturally to the larger address spaces that were becoming feasible in the 80s. This meant that nearly all of the programs composing ITS were obsolete. That put the last nail in the coffin of ITS; 15 years of work went up in smoke.

The modern computers of the era, such as the VAX or the 68020, had their own operating systems, but none of them were free software: you had to sign a nondisclosure agreement even to get an executable copy.

This meant that the first step in using a computer was to promise not to help your neighbor. A cooperating community was forbidden. The rule made by the owners of proprietary software was, “If you share with your neighbor, you are a pirate. If you want any changes, beg us to make them.”

The idea that the proprietary-software social system—the system that says you are not allowed to share or change software—is antisocial, that it is unethical, that it is simply wrong, may come as a surprise to some readers. But what else could we say about a system based on dividing the public and keeping users helpless? Readers who find the idea surprising may have taken this proprietary-software social system as given, or judged it on the terms suggested by proprietarysoftware businesses. Software publishers have worked long and hard to convince people that there is only one way to look at the issue.

When software publishers talk about “enforcing” their “rights” or “stopping piracy,” what they actually “say” is secondary. The real message of these statements is in the unstated assumptions they take for granted; the public is supposed to accept them uncritically. So let’s examine them.

One assumption is that software companies have an unquestionable natural right to own software and thus have power over all its users. (If this were a natural right, then no matter how much harm it does to the public, we could not object.) Interestingly, the U.S. Constitution and legal tradition reject this view; copyright is not a natural right, but an artificial government-imposed monopoly that limits the users’ natural right to copy.

Another unstated assumption is that the only important thing about software is what jobs it allows you to do—that we computer users should not care what kind of society we are allowed to have.