More languages

More actions

Free Software, Free Society | |

|---|---|

| Author | Richard Matthew Stallman |

| Publisher | Free Software Foundation |

| First published | 2010 |

| Type | Book |

| Source | https://annas-archive.org/md5/386a43f921ed1cc48c4cd7c1910ff073 |

| https://annas-archive.org/search?q=free+software+free+society | |

Editor's Note

The waning days of the 20th century seemed like an Orwellian nightmare: laws preventing publication of scientific research on software; laws preventing sharing software; an overabundance of software patents preventing development; and enduser license agreements that strip the user of all freedoms—including ownership, privacy, sharing, and understanding how their software works. This collection of essays and speeches by Richard M. Stallman addresses many of these issues. Above all, Stallman discusses the philosophy underlying the free software movement. This movement combats the oppression of federal laws and evil end-user license agreements in hopes of spreading the idea of software freedom.

With the force of hundreds of thousands of developers working to create GNU software and the GNU/Linux operating system, free software has secured a spot on the servers that control the Internet, and—as it moves into the desktop computer market—is a threat to Microsoft and other proprietary software companies.

These essays cater to a wide audience; you do not need a computer science background to understand the philosophy and ideas herein. However, there is a “Note on Software,” to help the less technically inclined reader become familiar with some common computer science jargon and concepts, as well as footnotes throughout.

Many of these essays have been updated and revised from their originally published version. Each essay carries permission to redistribute verbatim copies.

The ordering of the essays is fairly arbitrary, in that there is no required order to read the essays in, for they were written independently of each other over a period of 18 years. The first section, “The GNU Project and Free Software,” is intended to familiarize you with the history and philosophy of free software and the GNU project. Furthermore, it provides a road map for developers, educators, and business people to pragmatically incorporate free software into society, business, and life. The second section, “Copyright, Copyleft, and Patents,” discusses the philosophical and political groundings of the copyright and patent system and how it has changed over the past couple of hundred years. Also, it discusses how the current laws and regulations for patents and copyrights are not in the best interest of the consumer and end user of software, music, movies, and other media. Instead, this section discusses how laws are geared towards helping business and government crush your freedoms. The third section, “Freedom, Society, and Software” continues the discussion of freedom and rights, and how they are being threatened by proprietary software, copyright law, globalization, “trusted computing,” and other socially harmful rules, regulations, and policies. One way that industry and government are attempting to persuade people to give up certain rights and freedoms is by using terminology that implies that sharing information, ideas, and software is bad; therefore, we have included an essay explaining certain words that are confusing and should probably be avoided. The fourth section, “The Licenses,” contains the GNU General Public License, the GNU Lesser General Public License, and the GNU Free Documentation License; the cornerstones of the GNU project.

If you wish to purchase this book for yourself, for classroom use, or for distribution, please write to the Free Software Foundation (FSF) at sales@fsf.org or visit http://order.fsf.org/. If you wish to help further the cause of software freedom, please considering donating to the FSF by visiting http://donate.fsf.org (or write to donations@fsf.org for more details). You can also contact the FSF by phone at +1-617-542-5942.

There are perhaps thousands of people who should be thanked for their contributions to the GNU Project; however, their names will never fit on any single list. Therefore, I wish to extend my thanks to all of those nameless hackers, as well as people who have helped promote, create, and spread free software around the world.

For helping make this book possible, I would like to thank:

Julie Sussman, P.P.A., for editing multiple copies at various stages of development, for writing the “Topic Guide,” and for giving her insights into everything from commas to the ordering of the chapters;

Lisa (Opus) Goldstein and Bradley M. Kuhn for their help in organizing, proofreading, and generally making this collection possible;

Claire H. Avitabile, Richard Buckman, Tom Chenelle, and (especially) Stephen Compall for their careful proofreading of the entire collection;

Karl Berry, Bob Chassell, Michael Mounteney, and M. Ramakrishnan for their expertise in the helping to format and edit this collection in TEXinfo, (http://www.texinfo.org);

Mats Bengtsson for his help in formatting the Free Software Song in Lilypond (http://www.gnu.org/software/lilypond/);

Etienne Suvasa for the images that begin each section, and for all the art he has contributed to the Free Software Foundation over the years;

and Melanie Flanagan and Jason Polan for making helpful suggestions for the everyday reader. A special thanks to Bob Tocchio, from Paul’s Transmission Repair, for his insight on automobile transmissions.

Also, I wish to thank my mother and father, Wayne and Jo-Ann Gay, for teaching me that one should live by the ideals that one stands for, and for introducing me, my two brothers, and three sisters to the importance of sharing.

Lastly and most importantly, I would like to extend my gratitude to Richard M. Stallman for the GNU philosophy, the wonderful software, and the literature that he has shared with the world.

Joshua Gay

josh@gnu.org

A Note on Software

This section is intended for people who have little or no knowledge of the technical aspects of computer science. It is not necessary to read this section to understand the essays and speeches presented in this book; however, it may be helpful to those readers not familar with some of the jargon that comes with programming and computer science.

A computer programmer writes software, or computer programs. A program is more or less a recipe with commands to tell the computer what to do in order to carry out certain tasks. You are more than likely familiar with many different programs: your Web browser, your word processor, your email client, and the like.

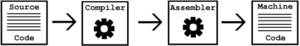

A program usually starts out as source code. This higher-level set of commands is written in a programming language such as C or Java. After that, a tool known as a compiler translates this to a lower-level language known as assembly language. Another tool known as an assembler breaks the assembly code down to the final stage of machine language—the lowest level—which the computer understands natively.

For example, consider the “hello world” program, a common first program for people learning C, which (when compiled and executed) prints “Hello World!” on the screen. [1]

int main(){

printf("Hello World!");

return 0;

}

In the Java programming language the same program would be written like this:

public class hello {

public static void main(String args[]) {

System.out.println(’’Hello World!’’);

}

}

However, in machine language, a small section of it may look similar to this:

1100011110111010100101001001001010101110

0110101010011000001111001011010101111101

0100111111111110010110110000000010100100

0100100001100101011011000110110001101111

0010000001010111011011110111001001101100

0110010000100001010000100110111101101111The above form of machine language is the most basic representation known as binary. All data in computers is made up of a series of 0-or-1 values, but a person would have much difficulty understanding the data. To make a simple change to the binary, one would have to have an intimate knowledge of how a particular computer interprets the machine language. This could be feasible for small programs like the above examples, but any interesting program would involve an exhausting effort to make simple changes. As an example, imagine that we wanted to make a change to our “Hello World” program written in C so that instead of printing “Hello World” in English it prints it in French. The change would be simple; here is the new program:

int main() {

printf("Bonjour, monde!");

return 0;

}

It is safe to say that one can easily infer how to change the program written in the Java programming language in the same way. However, even many programmers would not know where to begin if they wanted to change the binary representation. When we say “source code,” we do not mean machine language that only computers can understand—we are speaking of higher-level languages such as C and Java. A few other popular programming languages are C++, Perl, and Python. Some are harder than others to understand and program in, but they are all much easier to work with compared to the intricate machine language they get turned into after the programs are compiled and assembled.

Another important concept is understanding what an operating system is. An operating system is the software that handles input and output, memory allocation, and task scheduling. Generally one considers common or useful programs such as the Graphical User Interface (GUI) to be a part of the operating system. The GNU/Linux operating system contains a both GNU and non-GNU software, and a kernel called Linux. The kernel handles low-level tasks that applications depend upon such as input/output and task scheduling. The GNU software comprises much of the rest of the operating system, including GCC, a general-purpose compiler for many languages; GNU Emacs, an extensible text editor with many, many features; GNOME, the GNU desktop; GNU libc, a library that all programs other than the kernel must use in order to communicate with the kernel; and Bash, the GNU command interpreter that reads your command lines. Many of these programs were pioneered by Richard Stallman early on in the GNU Project and come with any modern GNU/Linux operating system.

It is important to understand that even if you cannot change the source code for a given program, or directly use all these tools, it is relatively easy to find someone who can. Therefore, by having the source code to a program you are usually given the power to change, fix, customize, and learn about a program—this is a power that you do not have if you are not given the source code. Source code is one of the requirements that makes a piece of software free. The other requirements will be found along with the philosophy and ideas behind them in this collection. Enjoy!

Richard E. Buckman

Joshua Gay

Section Footnotes

[1] In other programming languages, such as Scheme, the Hello World program is usually not your first program. In Scheme you often start with a program like this:

(define (factorial n)

(if (= n 0)

1

(* n (factorial (- n 1)))))

This computes the factorial of a number; that is, running (factorial 5) would output 120, which is computed by doing 5 * 4 * 3 * 2 * 1 * 1.

Topic Guide

Since the essays and speeches in this book were addressed to different audiences at different times, there is a considerable amount of overlap, with some issues being discussed in more than one place. Because of this, and because we did not have the opportunity to make an index for this book, it could be hard to go back to something you read about unless its location is obvious from a chapter title.

We hope that this short guide, though sketchy and incomplete (it does not cover all topics or all discussions of a given topic), will help you find some of the ideas and explanations you are interested in.

–Julie Sussman, P.P.A.

Overview

Chapter 1 gives an overview of just about all the software-related topics in this book. Chapter 20 is also an overview.

For the non-software topics, see Privacy and Personal Freedom, Intellectual Property, and Copyright, below.

GNU Project

For the history of the GNU project, see Chapters 1 and 20

For a delightful explanation of the origin and pronunciation of the recursive acronym GNU (GNU’s Not Unix, pronounced guh-NEW), see Chapter 20.

The “manifesto” that launched the GNU Project is included here as Chapter 2. See also the Linux, GNU/Linux topic below.

Free Software Foundation

You can read about the history and function of the Free Software Foundation in Chapters 1 and 20, and under “Funding Free Software” in Chapter 18.

Free software

We will not attempt to direct you to all discussions of free software in this book, since every chapter except 11, 12, 13, 16, 17, and 19 deals with free software. For a history of free software—from free software to proprietary software and back again—see Chapter 1.

Free Software is defined, and the definition discussed, in Chapter 3. The definition is repeated in several other chapters.

For a discussion of the ambiguity of the word “free” and why we still use it to mean “free” as in “free speech,” not as in “free beer,” see “Free as in Freedom” in Chapter 1 and “Ambiguity” in chapter 6.

See also Source Code, Open Source, and Copyleft, below. Free software is translated into 21 languages in Chapter 21.

Source Code, Source

Source code is mentioned throughout the discussions of free software. If you’re not sure what that is, read “A Note on Software.”

Linux, GNU/Linux

For the origin of Linux, and the distinction between Linux (the operating-system kernel) and GNU/Linux (a full operating system), see the short mention under “Linux and GNU/Linux” in Chapter 1 and the full story in Chapter 20/

For reasons to say GNU/Linux when referring to that operating system rather than abbreviating it to Linux see Chapters 5 and 20.

Privacy and Personal Freedom

For some warnings about the loss of personal freedom, privacy, and access to written material that we have long taken for granted, see Chapters 11, 13, and 17. All of these are geared to a general audience.

Open Source

For the difference between the Open Source movement and the Free Software movement, see Chapter 6. This is also discussed in Chapter 1 (under “Open Source”) and Chapter 20.

Intellectual Property

For an explanation of why the term “intellectual property” is both misleading and a barrier to addressing so-called “intellectual property” issues, see Chapter 21 and the beginning of Chapter 16.

For particular types of “intellectual property” see the Copyright and Patents topics, below.

Copyright

Note: Most of these copyright references are not about software.

For the history, purpose, implementation, and effects of copyright, as well as recommendations for copyright policy, see Chapters 12 and 19. Topics critical in our digital age, such as e-books and the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA), are addressed here.

For the difference between patents and copyrights, see Chapter 16.

For the use of copyright in promoting free software and free documentation, see Copyleft, just below.

Copyleft

For an explanation of copyleft and how it uses the copyright system to promote free software, see Chapter 1 (under “Copyleft and the GNU GPL”), Chapter 14, and Chapter 20. See also Licenses, below.

For an argument that copyleft is practical and effective as well as idealistic, see Chapter 15.

Chapter 9 argues for free manuals to accompany free software.

Licenses

The GNU licenses, which can be used to copyleft software or manuals, are introduced in Chapter 14 and given in full in Section Four.

Patents

See Chapter 16 for the difference between patents and copyrights and for arguments against patenting software and why it is different from other patentable things. Software-patent policy in other countries is also discussed.

Hacker versus Cracker

For the proper use of these terms see the beginning of Chapter 1.

Introduction

Every generation has its philosopher—a writer or an artist who captures the imagination of a time. Sometimes these philosophers are recognized as such; often it takes generations before the connection is made real. But recognized or not, a time gets marked by the people who speak its ideals, whether in the whisper of a poem, or the blast of a political movement.

Our generation has a philosopher. He is not an artist, or a professional writer. He is a programmer. Richard Stallman began his work in the labs of MIT, as a programmer and architect building operating system software. He has built his career on a stage of public life, as a programmer and an architect founding a movement for freedom in a world increasingly defined by “code.”

“Code” is the technology that makes computers run. Whether inscribed in software or burned in hardware, it is the collection of instructions, first written in words, that directs the functionality of machines. These machines—computers— increasingly define and control our life. They determine how phones connect, and what runs on TV. They decide whether video can be streamed across a broadband link to a computer. They control what a computer reports back to its manufacturer. These machines run us. Code runs these machines.

What control should we have over this code? What understanding? What freedom should there be to match the control it enables? What power?

These questions have been the challenge of Stallman’s life. Through his works and his words, he has pushed us to see the importance of keeping code “free.” Not free in the sense that code writers don’t get paid, but free in the sense that the control coders build be transparent to all, and that anyone have the right to take that control, and modify it as he or she sees fit. This is “free software”; “free software” is one answer to a world built in code.

“Free.” Stallman laments the ambiguity in his own term. There’s nothing to lament. Puzzles force people to think, and this term “free” does this puzzling work quite well. To modern American ears, “free software” sounds utopian, impossible. Nothing, not even lunch, is free. How could the most important words running the most critical machines running the world be “free.” How could a sane society aspire to such an ideal?

Yet the odd clink of the word “free” is a function of us, not of the term. “Free” has different senses, only one of which refers to “price.” A much more fundamental sense of “free” is the “free,” Stallman says, in the term “free speech,” or perhaps better in the term “free labor.” Not free as in costless, but free as in limited in its control by others. Free software is control that is transparent, and open to change, just as free laws, or the laws of a “free society,” are free when they make their control knowable, and open to change. The aim of Stallman’s “free software movement” is to make as much code as it can transparent, and subject to change, by rendering it “free.”

The mechanism of this rendering is an extraordinarily clever device called “copyleft” implemented through a license called GPL. Using the power of copyright law, “free software” not only assures that it remains open, and subject to change, but that other software that takes and uses “free software” (and that technically counts as a “derivative work”) must also itself be free. If you use and adapt a free software program, and then release that adapted version to the public, the released version must be as free as the version it was adapted from. It must, or the law of copyright will be violated.

“Free software,” like free societies, has its enemies. Microsoft has waged a war against the GPL, warning whoever will listen that the GPL is a “dangerous” license. The dangers it names, however, are largely illusory. Others object to the “coercion” in GPL’s insistence that modified versions are also free. But a condition is not coercion. If it is not coercion for Microsoft to refuse to permit users to distribute modified versions of its product Office without paying it (presumably) millions, then it is not coercion when the GPL insists that modified versions of free software be free too.

And then there are those who call Stallman’s message too extreme. But extreme it is not. Indeed, in an obvious sense, Stallman’s work is a simple translation of the freedoms that our tradition crafted in the world before code. “Free software” would assure that the world governed by code is as “free” as our tradition that built the world before code.

For example: A “free society” is regulated by law. But there are limits that any free society places on this regulation through law: No society that kept its laws secret could ever be called free. No government that hid its regulations from the regulated could ever stand in our tradition. Law controls. But it does so justly only when visibly. And law is visible only when its terms are knowable and controllable by those it regulates, or by the agents of those it regulates (lawyers, legislatures).

This condition on law extends beyond the work of a legislature. Think about the practice of law in American courts. Lawyers are hired by their clients to advance their clients’ interests. Sometimes that interest is advanced through litigation. In the course of this litigation, lawyers write briefs. These briefs in turn affect opinions written by judges. These opinions decide who wins a particular case, or whether a certain law can stand consistently with a constitution.

All the material in this process is free in the sense that Stallman means. Legal briefs are open and free for others to use. The arguments are transparent (which is different from saying they are good) and the reasoning can be taken without the permission of the original lawyers. The opinions they produce can be quoted in later briefs. They can be copied and integrated into another brief or opinion. The “source code” for American law is by design, and by principle, open and free for anyone to take. And take lawyers do—for it is a measure of a great brief that it achieves its creativity through the reuse of what happened before. The source is free; creativity and an economy is built upon it.

This economy of free code (and here I mean free legal code) doesn’t starve lawyers. Law firms have enough incentive to produce great briefs even though the stuff they build can be taken and copied by anyone else. The lawyer is a craftsman; his or her product is public. Yet the crafting is not charity. Lawyers get paid; the public doesn’t demand such work without price. Instead this economy flourishes, with later work added to the earlier.

We could imagine a legal practice that was different—briefs and arguments that were kept secret; rulings that announced a result but not the reasoning. Laws that were kept by the police but published to no one else. Regulation that operated without explaining its rule.

We could imagine this society, but we could not imagine calling it “free.” Whether or not the incentives in such a society would be better or more efficiently allocated, such a society could not be known as free. The ideals of freedom, of life within a free society, demand more than efficient application. Instead, openness and transparency are the constraints within which a legal system gets built, not options to be added if convenient to the leaders. Life governed by software code should be no less.

Code writing is not litigation. It is better, richer, more productive. But the law is an obvious instance of how creativity and incentives do not depend upon perfect control over the products created. Like jazz, or novels, or architecture, the law gets built upon the work that went before. This adding and changing is what creativity always is. And a free society is one that assures that its most important resources remain free in just this sense.

For the first time, this book collects the writing and lectures of Richard Stallman in a manner that will make their subtlety and power clear. The essays span a wide range, from copyright to the history of the free software movement. They include many arguments not well known, and among these, an especially insightful account of the changed circumstances that render copyright in the digital world suspect. They will serve as a resource for those who seek to understand the thought of this most powerful man—powerful in his ideas, his passion, and his integrity, even if powerless in every other way. They will inspire others who would take these ideas, and build upon them.

I don’t know Stallman well. I know him well enough to know he is a hard man to like. He is driven, often impatient. His anger can flare at friend as easily as foe. He is uncompromising and persistent; patient in both.

Yet when our world finally comes to understand the power and danger of code— when it finally sees that code, like laws, or like government, must be transparent to be free—then we will look back at this uncompromising and persistent programmer and recognize the vision he has fought to make real: the vision of a world where freedom and knowledge survives the compiler. And we will come to see that no man, through his deeds or words, has done as much to make possible the freedom that this next society could have.

We have not earned that freedom yet. We may well fail in securing it. But whether we succeed or fail, in these essays is a picture of what that freedom could be. And in the life that produced these words and works, there is inspiration for anyone who would, like Stallman, fight to create this freedom.

Lawrence Lessig

Professor of Law, Stanford Law School.

Chapter One: The GNU Project and Free Software

The First Software-Sharing Community

When I started working at the MIT Artificial Intelligence Lab in 1971, I became part of a software-sharing community that had existed for many years. Sharing of software was not limited to our particular community; it is as old as computers, just as sharing of recipes is as old as cooking. But we did it more than most.

The AI Lab used a timesharing operating system called ITS (the Incompatible Timesharing System) that the lab’s staff hackers had designed and written in assembler language for the Digital PDP-10, one of the large computers of the era. As a member of this community, an AI lab staff system hacker, my job was to improve this system.

We did not call our software “free software,” because that term did not yet exist; but that is what it was. Whenever people from another university or a company wanted to port and use a program, we gladly let them. If you saw someone using an unfamiliar and interesting program, you could always ask to see the source code, so that you could read it, change it, or cannibalize parts of it to make a new program.

The use of “hacker” to mean “security breaker” is a confusion on the part of the mass media. We hackers refuse to recognize that meaning, and continue using the word to mean, “Someone who loves to program and enjoys being clever about it.”[1]

The Collapse of the Community

The situation changed drastically in the early 1980s, with the collapse of the AI Lab hacker community followed by the discontinuation of the PDP-10 computer.

In 1981, the spin-off company Symbolics hired away nearly all of the hackers from the AI Lab, and the depopulated community was unable to maintain itself. (The book Hackers, by Steven Levy, describes these events, as well as giving a clear picture of this community in its prime.) When the AI Lab bought a new PDP10 in 1982, its administrators decided to use Digital’s non-free timesharing system instead of ITS on the new machine.

Not long afterwards, Digital discontinued the PDP-10 series. Its architecture, elegant and powerful in the 60s, could not extend naturally to the larger address spaces that were becoming feasible in the 80s. This meant that nearly all of the programs composing ITS were obsolete. That put the last nail in the coffin of ITS; 15 years of work went up in smoke.

The modern computers of the era, such as the VAX or the 68020, had their own operating systems, but none of them were free software: you had to sign a nondisclosure agreement even to get an executable copy.

This meant that the first step in using a computer was to promise not to help your neighbor. A cooperating community was forbidden. The rule made by the owners of proprietary software was, “If you share with your neighbor, you are a pirate. If you want any changes, beg us to make them.”

The idea that the proprietary-software social system—the system that says you are not allowed to share or change software—is antisocial, that it is unethical, that it is simply wrong, may come as a surprise to some readers. But what else could we say about a system based on dividing the public and keeping users helpless? Readers who find the idea surprising may have taken this proprietary-software social system as given, or judged it on the terms suggested by proprietarysoftware businesses. Software publishers have worked long and hard to convince people that there is only one way to look at the issue.

When software publishers talk about “enforcing” their “rights” or “stopping piracy,” what they actually “say” is secondary. The real message of these statements is in the unstated assumptions they take for granted; the public is supposed to accept them uncritically. So let’s examine them.

One assumption is that software companies have an unquestionable natural right to own software and thus have power over all its users. (If this were a natural right, then no matter how much harm it does to the public, we could not object.) Interestingly, the U.S. Constitution and legal tradition reject this view; copyright is not a natural right, but an artificial government-imposed monopoly that limits the users’ natural right to copy.

Another unstated assumption is that the only important thing about software is what jobs it allows you to do—that we computer users should not care what kind of society we are allowed to have.

A third assumption is that we would have no usable software (or would never have a program to do this or that particular job) if we did not offer a company power over the users of the program. This assumption may have seemed plausible before the free software movement demonstrated that we can make plenty of useful software without putting chains on it.

If we decline to accept these assumptions, and judge these issues based on ordinary common-sense morality while placing the users first, we arrive at very different conclusions. Computer users should be free to modify programs to fit their needs, and free to share software, because helping other people is the basis of society.

A Stark Moral Choice

With my community gone, to continue as before was impossible. Instead, I faced a stark moral choice.

The easy choice was to join the proprietary software world, signing nondisclosure agreements and promising not to help my fellow hacker. Most likely I would also be developing software that was released under nondisclosure agreements, thus adding to the pressure on other people to betray their fellows too.

I could have made money this way, and perhaps amused myself writing code. But I knew that at the end of my career, I would look back on years of building walls to divide people, and feel I had spent my life making the world a worse place.

I had already experienced being on the receiving end of a nondisclosure agreement, when someone refused to give me and the MIT AI Lab the source code for the control program for our printer. (The lack of certain features in this program made use of the printer extremely frustrating.) So I could not tell myself that nondisclosure agreements were innocent. I was very angry when he refused to share with us; I could not turn around and do the same thing to everyone else.

Another choice, straightforward but unpleasant, was to leave the computer field. That way my skills would not be misused, but they would still be wasted. I would not be culpable for dividing and restricting computer users, but it would happen nonetheless.

So I looked for a way that a programmer could do something for the good. I asked myself, was there a program or programs that I could write, so as to make a community possible once again?

The answer was clear: what was needed first was an operating system. That is the crucial software for starting to use a computer. With an operating system, you can do many things; without one, you cannot run the computer at all. With a free operating system, we could again have a community of cooperating hackers—and invite anyone to join. And anyone would be able to use a computer without starting out by conspiring to deprive his or her friends.

As an operating system developer, I had the right skills for this job. So even though I could not take success for granted, I realized that I was elected to do the job. I chose to make the system compatible with Unix so that it would be portable, and so that Unix users could easily switch to it. The name GNU was chosen following a hacker tradition, as a recursive acronym for “GNU’s Not Unix.”

An operating system does not mean just a kernel, barely enough to run other programs. In the 1970s, every operating system worthy of the name included command processors, assemblers, compilers, interpreters, debuggers, text editors, mailers, and much more. ITS had them, Multics had them, VMS had them, and Unix had them. The GNU operating system would include them too.

Later I heard these words, attributed to Hillel:

“If I am not for myself, who will be for me? If I am only for myself, what am I? If not now, when?”

The decision to start the GNU project was based on a similar spirit.

As an atheist, I don’t follow any religious leaders, but I sometimes find I admire something one of them has said.

The term “free software” is sometimes misunderstood—it has nothing to do with price. It is about freedom. Here, therefore, is the definition of free software: a program is free software, for you, a particular user, if:

- You have the freedom to run the program, for any purpose.

- You have the freedom to modify the program to suit your needs. (To make this freedom effective in practice, you must have access to the source code, since making changes in a program without having the source code is exceedingly difficult.)

- You have the freedom to redistribute copies, either gratis or for a fee.

- You have the freedom to distribute modified versions of the program, so that the community can benefit from your improvements.

Since “free” refers to freedom, not to price, there is no contradiction between selling copies and free software. In fact, the freedom to sell copies is crucial: collections of free software sold on CD-ROMs are important for the community, and selling them is an important way to raise funds for free software development. Therefore, a program that people are not free to include on these collections is not free software.

Because of the ambiguity of “free,” people have long looked for alternatives, but no one has found a suitable alternative. The English Language has more words and nuances than any other, but it lacks a simple, unambiguous word that means “free,” as in freedom—“unfettered” being the word that comes closest in meaning. Such alternatives as “liberated,” “freedom,” and “open” have either the wrong meaning or some other disadvantage.

GNU Software and the GNU System

Developing a whole system is a very large project. To bring it into reach, I decided to adapt and use existing pieces of free software wherever that was possible. For example, I decided at the very beginning to use TeX as the principal text formatter; a few years later, I decided to use the X Window System rather than writing another window system for GNU.

Because of this decision, the GNU system is not the same as the collection of all GNU software. The GNU system includes programs that are not GNU software, programs that were developed by other people and projects for their own purposes, but that we can use because they are free software.

Commencing the Project

In January 1984 I quit my job at MIT and began writing GNU software. Leaving MIT was necessary so that MIT would not be able to interfere with distributing GNU as free software. If I had remained on the staff, MIT could have claimed to own the work, and could have imposed their own distribution terms, or even turned the work into a proprietary software package. I had no intention of doing a large amount of work only to see it become useless for its intended purpose: creating a new software-sharing community.

However, Professor Winston, then the head of the MIT AI Lab, kindly invited me to keep using the lab’s facilities.

The First Steps

Shortly before beginning the GNU project, I heard about the Free University Compiler Kit, also known as VUCK. (The Dutch word for “free” is written with a V.) This was a compiler designed to handle multiple languages, including C and Pascal, and to support multiple target machines. I wrote to its author asking if GNU could use it.Shortly before beginning the GNU project, I heard about the Free University Compiler Kit, also known as VUCK. (The Dutch word for “free” is written with a V.) This was a compiler designed to handle multiple languages, including C and Pascal, and to support multiple target machines. I wrote to its author asking if GNU could use it.

He responded derisively, stating that the university was free but the compiler was not. I therefore decided that my first program for the GNU project would be a multi-language, multi-platform compiler.

Hoping to avoid the need to write the whole compiler myself, I obtained the source code for the Pastel compiler, which was a multi-platform compiler developed at Lawrence Livermore Lab. It supported, and was written in, an extended version of Pascal, designed to be a system-programming language. I added a C front end, and began porting it to the Motorola 68000 computer. But I had to give that up when I discovered that the compiler needed many megabytes of stack space, and the available 68000 Unix system would only allow 64k.

I then realized that the Pastel compiler functioned by parsing the entire input file into a syntax tree, converting the whole syntax tree into a chain of “instructions,” and then generating the whole output file, without ever freeing any storage. At this point, I concluded I would have to write a new compiler from scratch. That new compiler is now known as GCC; none of the Pastel compiler is used in it, but I managed to adapt and use the C front end that I had written. But that was some years later; first, I worked on GNU Emacs.

GNU Emacs

I began work on GNU Emacs in September 1984, and in early 1985 it was beginning to be usable. This enabled me to begin using Unix systems to do editing; having no interest in learning to use vi or ed, I had done my editing on other kinds of machines until then.

At this point, people began wanting to use GNU Emacs, which raised the question of how to distribute it. Of course, I put it on the anonymous ftp server on the MIT computer that I used. (This computer, prep.ai.mit.edu, thus became the principal GNU ftp distribution site; when it was decommissioned a few years later, we transferred the name to our new ftp server.) But at that time, many of the interested people were not on the Internet and could not get a copy by ftp. So the question was, what would I say to them?

I could have said, “Find a friend who is on the net and who will make a copy for you.” Or I could have done what I did with the original PDP-10 Emacs: tell them, “Mail me a tape and a SASE, and I will mail it back with Emacs on it.” But I had no job and I was looking for ways to make money from free software. So I announced that I would mail a tape to whoever wanted one, for a fee of $150. In this way, I started a free software distribution business, the precursor of the companies that today distribute entire Linux-based GNU systems.

Is a program free for every user?

If a program is free software when it leaves the hands of its author, this does not necessarily mean it will be free software for everyone who has a copy of it. For example, public domain software (software that is not copyrighted) is free software; but anyone can make a proprietary modified version of it. Likewise, many free programs are copyrighted but distributed under simple permissive licenses that allow proprietary modified versions.

The paradigmatic example of this problem is the X Window System. Developed at MIT, and released as free software with a permissive license, it was soon adopted by various computer companies. They added X to their proprietary Unix systems, in binary form only, and covered by the same nondisclosure agreement. These copies of X were no more free software than Unix was.

The developers of the X Window System did not consider this a problem—they expected and intended this to happen. Their goal was not freedom, just “success,” defined as “having many users.” They did not care whether these users had freedom, only that they should be numerous.

This lead to a paradoxical situation where two different ways of counting the amount of freedom gave different answers to the question, “Is this program free?” If you judged based on the freedom provided by the distribution terms of the MIT release, you would say that X was free software. But if you measured the freedom of the average user of X, you would have to say it was proprietary software. Most X users were running the proprietary versions that came with Unix systems, not the free version.

Copyleft and the GNU GPL

The goal of GNU was to give users freedom, not just to be popular. So we needed to use distribution terms that would prevent GNU software from being turned into proprietary software. The method we use is called copyleft.

Copyleft uses copyright law, but flips it over to serve the opposite of its usual purpose: instead of a means of privatizing software, it becomes a means of keeping software free.

The central idea of copyleft is that we give everyone permission to run the program, copy the program, modify the program, and distribute modified versions— but not permission to add restrictions of their own. Thus, the crucial freedoms that define “free software” are guaranteed to everyone who has a copy; they become inalienable rights.

For an effective copyleft, modified versions must also be free. This ensures that work based on ours becomes available to our community if it is published. When programmers who have jobs as programmers volunteer to improve GNU software, it is copyleft that prevents their employers from saying, “You can’t share those changes, because we are going to use them to make our proprietary version of the program.”

The requirement that changes must be free is essential if we want to ensure freedom for every user of the program. The companies that privatized the X Window System usually made some changes to port it to their systems and hardware. These changes were small compared with the great extent of X, but they were not trivial. If making changes were an excuse to deny the users freedom, it would be easy for anyone to take advantage of the excuse.

A related issue concerns combining a free program with non-free code. Such a combination would inevitably be non-free; whichever freedoms are lacking for the non-free part would be lacking for the whole as well. To permit such combinations would open a hole big enough to sink a ship. Therefore, a crucial requirement for copyleft is to plug this hole: anything added to or combined with a copylefted program must be such that the larger combined version is also free and copylefted.

The specific implementation of copyleft that we use for most GNU software is the GNU General Public License, or GNU GPL for short. We have other kinds of copyleft that are used in specific circumstances. GNU manuals are copylefted also, but use a much simpler kind of copyleft, because the complexity of the GNU GPL is not necessary for manuals.

In 1984 or 1985, Don Hopkins (a very imaginative fellow) mailed me a letter. On the envelope he had written several amusing sayings, including this one: “Copyleft—all rights reversed.” I used the word “copyleft” to name the distribution concept I was developing at the time.

The Free Software Foundation

As interest in using Emacs was growing, other people became involved in the GNU project, and we decided that it was time to seek funding once again. So in 1985 we created the Free Software Foundation, a tax-exempt charity for free software development. The FSF also took over the Emacs tape distribution business; later it extended this by adding other free software (both GNU and non-GNU) to the tape, and by selling free manuals as well.

The FSF accepts donations, but most of its income has always come from sales— of copies of free software, and of other related services. Today it sells CD-ROMs of source code, CD-ROMs with binaries, nicely printed manuals (all with freedom to redistribute and modify), and Deluxe Distributions (where we build the whole collection of software for your choice of platform).

Free Software Foundation employees have written and maintained a number of GNU software packages. Two notable ones are the C library and the shell. The GNU C library is what every program running on a GNU/Linux system uses to communicate with Linux. It was developed by a member of the Free Software Foundation staff, Roland McGrath. The shell used on most GNU/Linux systems is BASH, the Bourne Again Shell, which was developed by FSF employee Brian Fox.

We funded development of these programs because the GNU project was not just about tools or a development environment. Our goal was a complete operating system, and these programs were needed for that goal.

“Bourne again Shell” is a joke on the name “Bourne Shell,” which was the usual shell on Unix.

Free Software Support

The free software philosophy rejects a specific widespread business practice, but it is not against business. When businesses respect the users’ freedom, we wish them success.

Selling copies of Emacs demonstrates one kind of free software business. When the FSF took over that business, I needed another way to make a living. I found it in selling services relating to the free software I had developed. This included teaching, for subjects such as how to program GNU Emacs and how to customize GCC, and software development, mostly porting GCC to new platforms.

Today each of these kinds of free software business is practiced by a number of corporations. Some distribute free software collections on CD-ROM; others sell support at various levels ranging from answering user questions, to fixing bugs, to adding major new features. We are even beginning to see free software companies based on launching new free software products.

Watch out, though—a number of companies that associate themselves with the term “open source” actually base their business on non-free software that works with free software. These are not free software companies, they are proprietary software companies whose products tempt users away from freedom. They call these “value added,” which reflects the values they would like us to adopt: convenience above freedom. If we value freedom more, we should call them “freedom subtracted” products.

Technical goals

The principal goal of GNU was to be free software. Even if GNU had no technical advantage over Unix, it would have a social advantage, allowing users to cooperate, and an ethical advantage, respecting the user’s freedom.

But it was natural to apply the known standards of good practice to the work—for example, dynamically allocating data structures to avoid arbitrary fixed size limits, and handling all the possible 8-bit codes wherever that made sense.

In addition, we rejected the Unix focus on small memory size, by deciding not to support 16-bit machines (it was clear that 32-bit machines would be the norm by the time the GNU system was finished), and to make no effort to reduce memory usage unless it exceeded a megabyte. In programs for which handling very large files was not crucial, we encouraged programmers to read an entire input file into core, then scan its contents without having to worry about I/O.

These decisions enabled many GNU programs to surpass their Unix counterparts in reliability and speed.

Donated Computers

As the GNU project’s reputation grew, people began offering to donate machines running Unix to the project. These were very useful, because the easiest way to develop components of GNU was to do it on a Unix system, and replace the components of that system one by one. But they raised an ethical issue: whether it was right for us to have a copy of Unix at all.

Unix was (and is) proprietary software, and the GNU project’s philosophy said that we should not use proprietary software. But, applying the same reasoning that leads to the conclusion that violence in self defense is justified, I concluded that it was legitimate to use a proprietary package when that was crucial for developing a free replacement that would help others stop using the proprietary package.

But, even if this was a justifiable evil, it was still an evil. Today we no longer have any copies of Unix, because we have replaced them with free operating systems. If we could not replace a machine’s operating system with a free one, we replaced the machine instead.

The GNU Task List

As the GNU project proceeded, and increasing numbers of system components were found or developed, eventually it became useful to make a list of the remaining gaps. We used it to recruit developers to write the missing pieces. This list became known as the GNU task list. In addition to missing Unix components, we listed various other useful software and documentation projects that, we thought, a truly complete system ought to have.

Today, hardly any Unix components are left in the GNU task list—those jobs have been done, aside from a few inessential ones. But the list is full of projects that some might call “applications.” Any program that appeals to more than a narrow class of users would be a useful thing to add to an operating system.

Even games are included in the task list—and have been since the beginning. Unix included games, so naturally GNU should too. But compatibility was not an issue for games, so we did not follow the list of games that Unix had. Instead, we listed a spectrum of different kinds of games that users might like.

The GNU Library GPL

The GNU C library uses a special kind of copyleft called the GNU Library General Public License, which gives permission to link proprietary software with the library. Why make this exception?

It is not a matter of principle; there is no principle that says proprietary software products are entitled to include our code. (Why contribute to a project predicated on refusing to share with us?) Using the LGPL for the C library, or for any library, is a matter of strategy.

The C library does a generic job; every proprietary system or compiler comes with a C library. Therefore, to make our C library available only to free software would not have given free software any advantage—it would only have discouraged use of our library.

One system is an exception to this: on the GNU system (and this includes GNU/Linux), the GNU C library is the only C library. So the distribution terms of the GNU C library determine whether it is possible to compile a proprietary program for the GNU system. There is no ethical reason to allow proprietary applications on the GNU system, but strategically it seems that disallowing them would do more to discourage use of the GNU system than to encourage development of free applications.

That is why using the Library GPL is a good strategy for the C library. For other libraries, the strategic decision needs to be considered on a case-by-case basis. When a library does a special job that can help write certain kinds of programs, then releasing it under the GPL, limiting it to free programs only, is a way of helping other free software developers, giving them an advantage against proprietary software.

Consider GNU Readline[2] a library that was developed to provide commandline editing for BASH. Readline is released under the ordinary GNU GPL, not the Library GPL. This probably does reduce the amount Readline is used, but that is no loss for us. Meanwhile, at least one useful application has been made free software specifically so it could use Readline, and that is a real gain for the community.

Proprietary software developers have the advantages money provides; free software developers need to make advantages for each other. I hope some day we will have a large collection of GPL-covered libraries that have no parallel available to proprietary software, providing useful modules to serve as building blocks in new free software, and adding up to a major advantage for further free software development.

Scratching an itch?

Eric Raymond says that “Every good work of software starts by scratching a developer’s personal itch.” Maybe that happens sometimes, but many essential pieces of GNU software were developed in order to have a complete free operating system. They come from a vision and a plan, not from impulse.

For example, we developed the GNU C library because a Unix-like system needs a C library, the Bourne Again Shell (BASH) because a Unix-like system needs a shell, and GNU tar because a Unix-like system needs a tar program. The same is true for my own programs—the GNU C compiler, GNU Emacs, GDB and GNU Make.

Some GNU programs were developed to cope with specific threats to our freedom. Thus, we developed gzip to replace the Compress program, which had been lost to the community because of the LZW[3] patents. We found people to develop LessTif, and more recently started GNOME and Harmony, to address the problems caused by certain proprietary libraries (see “Non-Free Libraries” below). We are developing the GNU Privacy Guard to replace popular non-free encryption software, because users should not have to choose between privacy and freedom.

Of course, the people writing these programs became interested in the work, and many features were added to them by various people for the sake of their own needs and interests. But that is not why the programs exist.

Unexpected Developments

At the beginning of the GNU project, I imagined that we would develop the whole GNU system, then release it as a whole. That is not how it happened. Since each component of the GNU system was implemented on a Unix system, each component could run on Unix systems, long before a complete GNU system existed. Some of these programs became popular, and users began extending them and porting them—to the various incompatible versions of Unix, and sometimes to other systems as well.

The process made these programs much more powerful, and attracted both funds and contributors to the GNU project. But it probably also delayed completion of a minimal working system by several years, as GNU developers’ time was put into maintaining these ports and adding features to the existing components, rather than moving on to write one missing component after another.

The GNU Hurd

By 1990, the GNU system was almost complete; the only major missing component was the kernel. We had decided to implement our kernel as a collection of server processes running on top of Mach. Mach is a microkernel developed at Carnegie Mellon University and then at the University of Utah; the GNU Hurd is a collection of servers (or “herd of gnus”) that run on top of Mach, and do the various jobs of the Unix kernel. The start of development was delayed as we waited for Mach to be released as free software, as had been promised.

One reason for choosing this design was to avoid what seemed to be the hardest part of the job: debugging a kernel program without a source-level debugger to do it with. This part of the job had been done already, in Mach, and we expected to debug the Hurd servers as user programs, with GDB. But it took a long time to make that possible, and the multi-threaded servers that send messages to each other have turned out to be very hard to debug. Making the Hurd work solidly has stretched on for many years.

Alix

The GNU kernel was not originally supposed to be called the Hurd. Its original name was Alix—named after the woman who was my sweetheart at the time. She, a Unix system administrator, had pointed out how her name would fit a common naming pattern for Unix system versions; as a joke, she told her friends, “Someone should name a kernel after me.” I said nothing, but decided to surprise her with a kernel named Alix.

It did not stay that way. Michael Bushnell (now Thomas), the main developer of the kernel, preferred the name Hurd, and redefined Alix to refer to a certain part of the kernel—the part that would trap system calls and handle them by sending messages to Hurd servers.

Ultimately, Alix and I broke up, and she changed her name; independently, the Hurd design was changed so that the C library would send messages directly to servers, and this made the Alix component disappear from the design.

But before these things happened, a friend of hers came across the name Alix in the Hurd source code, and mentioned the name to her. So the name did its job.

Linux and GNU/Linux

The GNU Hurd is not ready for production use. Fortunately, another kernel is available. In 1991, Linus Torvalds developed a Unix-compatible kernel and called it Linux. Around 1992, combining Linux with the not-quite-complete GNU system resulted in a complete free operating system. (Combining them was a substantial job in itself, of course.) It is due to Linux that we can actually run a version of the GNU system today.

We call this system version GNU/Linux, to express its composition as a combination of the GNU system with Linux as the kernel.

Challenges in Our Future

We have proved our ability to develop a broad spectrum of free software. This does not mean we are invincible and unstoppable. Several challenges make the future of free software uncertain; meeting them will require steadfast effort and endurance, sometimes lasting for years. It will require the kind of determination that people display when they value their freedom and will not let anyone take it away.

The following four sections discuss these challenges.

Secret Hardware

Hardware manufactures increasingly tend to keep hardware specifications secret. This makes it difficult to write free drivers so that Linux and XFree86[4] can support new hardware. We have complete free systems today, but we will not have them tomorrow if we cannot support tomorrow’s computers.

There are two ways to cope with this problem. Programmers can do reverse engineering to figure out how to support the hardware. The rest of us can choose the hardware that is supported by free software; as our numbers increase, secrecy of specifications will become a self-defeating policy.

Reverse engineering is a big job; will we have programmers with sufficient determination to undertake it? Yes—if we have built up a strong feeling that free software is a matter of principle, and non-free drivers are intolerable. And will large numbers of us spend extra money, or even a little extra time, so we can use free drivers? Yes, if the determination to have freedom is widespread.

Non-Free Libraries

A non-free library that runs on free operating systems acts as a trap for free software developers. The library’s attractive features are the bait; if you use the library, you fall into the trap, because your program cannot usefully be part of a free operating system. (Strictly speaking, we could include your program, but it won’t run with the library missing.) Even worse, if a program that uses the proprietary library becomes popular, it can lure other unsuspecting programmers into the trap.

The first instance of this problem was the Motif[5] toolkit, back in the 80s. Although there were as yet no free operating systems, it was clear what problem Motif would cause for them later on. The GNU Project responded in two ways: by asking individual free software projects to support the free X toolkit widgets as well as Motif, and by asking for someone to write a free replacement for Motif. The job took many years; LessTif, developed by the Hungry Programmers, became powerful enough to support most Motif applications only in 1997.

Between 1996 and 1998, another non-free Graphical User Interface (GUI) toolkit library, called Qt, was used in a substantial collection of free software, the desktop KDE.

Free GNU/Linux systems were unable to use KDE, because we could not use the library. However, some commercial distributors of GNU/Linux systems who were not strict about sticking with free software added KDE to their systems— producing a system with more capabilities, but less freedom. The KDE group was actively encouraging more programmers to use Qt, and millions of new “Linux users” had never been exposed to the idea that there was a problem in this. The situation appeared grim.

The free software community responded to the problem in two ways: GNOME and Harmony.

GNOME, the GNU Network Object Model Environment, is GNU’s desktop project. Started in 1997 by Miguel de Icaza, and developed with the support of Red Hat Software, GNOME set out to provide similar desktop facilities, but using free software exclusively. It has technical advantages as well, such as supporting a variety of languages, not just C++. But its main purpose was freedom: not to require the use of any non-free software.

Harmony is a compatible replacement library, designed to make it possible to run KDE software without using Qt

In November 1998, the developers of Qt announced a change of license which, when carried out, should make Qt free software. There is no way to be sure, but I think that this was partly due to the community’s firm response to the problem that Qt posed when it was non-free. (The new license is inconvenient and inequitable, so it remains desirable to avoid using Qt.)[6]

How will we respond to the next tempting non-free library? Will the whole community understand the need to stay out of the trap? Or will many of us give up freedom for convenience, and produce a major problem? Our future depends on our philosophy.

Software Patents

The worst threat we face comes from software patents, which can put algorithms and features off limits to free software for up to twenty years. The LZW compression algorithm patents were applied for in 1983, and we still cannot release free software to produce proper compressed GIFs. In 1998, a free program to produce MP3 compressed audio was removed from distribution under threat of a patent suit.

There are ways to cope with patents: we can search for evidence that a patent is invalid, and we can look for alternative ways to do a job. But each of these methods works only sometimes; when both fail, a patent may force all free software to lack some feature that users want. What will we do when this happens?

Those of us who value free software for freedom’s sake will stay with free software anyway. We will manage to get work done without the patented features. But those who value free software because they expect it to be techically superior are likely to call it a failure when a patent holds it back. Thus, while it is useful to talk about the practical effectiveness of the “cathedral” model of development,[7] and the reliability and power of some free software, we must not stop there. We must talk about freedom and principle.

Free Documentation

The biggest deficiency in our free operating systems is not in the software—it is the lack of good free manuals that we can include in our systems. Documentation is an essential part of any software package; when an important free software package does not come with a good free manual, that is a major gap. We have many such gaps today.

Free documentation, like free software, is a matter of freedom, not price. The criterion for a free manual is pretty much the same as for free software: it is a matter of giving all users certain freedoms. Redistribution (including commercial sale) must be permitted, on-line and on paper, so that the manual can accompany every copy of the program.

Permission for modification is crucial too. As a general rule, I don’t believe that it is essential for people to have permission to modify all sorts of articles and books. For example, I don’t think you or I are obliged to give permission to modify articles like this one, which describe our actions and our views.

But there is a particular reason why the freedom to modify is crucial for documentation for free software. When people exercise their right to modify the software, and add or change its features, if they are conscientious they will change the manual too—so they can provide accurate and usable documentation with the modified program. A manual that does not allow programmers to be conscientious and finish the job does not fill our community’s needs.

Some kinds of limits on how modifications are done pose no problem. For example, requirements to preserve the original author’s copyright notice, the distribution terms, or the list of authors, are ok. It is also no problem to require modified versions to include notice that they were modified, even to have entire sections that may not be deleted or changed, as long as these sections deal with nontechnical topics. These kinds of restrictions are not a problem because they don’t stop the conscientious programmer from adapting the manual to fit the modified program. In other words, they don’t block the free software community from making full use of the manual.

However, it must be possible to modify all the “technical” content of the manual, and then distribute the result in all the usual media, through all the usual channels; otherwise, the restrictions do obstruct the community, the manual is not free, and we need another manual.

Will free software developers have the awareness and determination to produce a full spectrum of free manuals? Once again, our future depends on philosophy

We Must Talk About Freedom

Estimates today are that there are ten million users of GNU/Linux systems such as Debian GNU/Linux and Red Hat Linux. Free software has developed such practical advantages that users are flocking to it for purely practical reasons.

The good consequences of this are evident: more interest in developing free software, more customers for free software businesses, and more ability to encourage companies to develop commercial free software instead of proprietary software products.

But interest in the software is growing faster than awareness of the philosophy it is based on, and this leads to trouble. Our ability to meet the challenges and threats described above depends on the will to stand firm for freedom. To make sure our community has this will, we need to spread the idea to the new users as they come into the community

But we are failing to do so: the efforts to attract new users into our community are far outstripping the efforts to teach them the civics of our community. We need to do both, and we need to keep the two efforts in balance.

"Open Source"

Teaching new users about freedom became more difficult in 1998, when a part of the community decided to stop using the term “free software” and say “open source software” instead.

Some who favored this term aimed to avoid the confusion of “free” with “gratis”—a valid goal. Others, however, aimed to set aside the spirit of principle that had motivated the free software movement and the GNU project, and to appeal instead to executives and business users, many of whom hold an ideology that places profit above freedom, above community, above principle. Thus, the rhetoric of “open source” focuses on the potential to make high-quality, powerful software, but shuns the ideas of freedom, community, and principle.

The “Linux” magazines are a clear example of this—they are filled with advertisements for proprietary software that works with GNU/Linux. When the next Motif or Qt appears, will these magazines warn programmers to stay away from it, or will they run ads for it?

The support of business can contribute to the community in many ways; all else being equal, it is useful. But winning their support by speaking even less about freedom and principle can be disastrous; it makes the previous imbalance between outreach and civics education even worse.

“Free software” and “open source” describe the same category of software, more or less, but say different things about the software, and about values. The GNU Project continues to use the term “free software,” to express the idea that freedom, not just technology, is important.

Try!

Yoda’s philosophy (“There is no ‘try”’) sounds neat, but it doesn’t work for me. I have done most of my work while anxious about whether I could do the job, and unsure that it would be enough to achieve the goal if I did. But I tried anyway, because there was no one but me between the enemy and my city. Surprising myself, I have sometimes succeeded.

Sometimes I failed; some of my cities have fallen. Then I found another threatened city, and got ready for another battle. Over time, I’ve learned to look for threats and put myself between them and my city, calling on other hackers to come and join me.

Nowadays, often I’m not the only one. It is a relief and a joy when I see a regiment of hackers digging in to hold the line, and I realize, this city may survive— for now. But the dangers are greater each year, and now Microsoft has explicitly targeted our community. We can’t take the future of freedom for granted. Don’t take it for granted! If you want to keep your freedom, you must be prepared to defend it.

Chapter Footnotes

[1] It is hard to write a simple definition of something as varied as hacking, but I think what most “hacks” have in common is playfulness, cleverness, and exploration. Thus, hacking means exploring the limits of what is possible, in a spirit of playful cleverness. Activities that display playful cleverness have “hack value.” You can help correct the misunderstanding simply by making a distinction between security breaking and hacking—by using the term “cracking” for security breaking. The people who do it are “crackers.” Some of them may also be hackers, just as some of them may be chess players or golfers; most of them are not (“On Hacking,” RMS; 2002).

[2] The GNU Readline library provides a set of functions for use by applications that allow users to edit command lines as they are typed in.

[3] The Lempel-Ziv-Welch algorithm is used for compressing data.

[4] XFree86 is a program that provides a desktop environment that interfaces with your display hardware (mouse, keyboard, etc). It runs on many different platforms.

[5] Motif is a graphical interface and window manager that runs on top of X Windows.

[6] In September 2000, Qt was rereleased under the GNU GPL, which essentially solved this problem.

[7] I probably meant to write “of the ‘bazaar’ model,” since that was the alternative that was new and initially controversial.

Chapter 2: The GNU Manifesto

The GNU Manifesto was written at the beginning of the GNU Project, to ask for participation and support. For the first few years, it was updated in minor ways to account for developments, but now it seems best to leave it unchanged as most people have seen it. Since that time, we have learned about certain common misunderstandings that different wording could help avoid, and footnotes have been added over the years to explain these misunderstandings.

What's GNU? GNU's Not Unix!

GNU, which stands for Gnu’s Not Unix, is the name for the complete Unix-compatible software system which I am writing so that I can give it away free to everyone who can use it[1]. Several other volunteers are helping me. Contributions of time, money, programs and equipment are greatly needed.

So far we have an Emacs text editor with Lisp for writing editor commands, a source-level debugger, a yacc-compatible parser generator, a linker, and around 35 utilities. A shell (command interpreter) is nearly completed. A new portable optimizing C compiler has compiled itself and may be released this year. An initial kernel exists but many more features are needed to emulate Unix. When the kernel and compiler are finished, it will be possible to distribute a GNU system suitable for program development. We will use TEX as our text formatter, but an nroff is being worked on. We will use the free, portable X window system as well. After this we will add a portable Common Lisp, an Empire game, a spreadsheet, and hundreds of other things, plus on-line documentation. We hope to supply, eventually, everything useful that normally comes with a Unix system, and more.

GNU will be able to run Unix programs, but will not be identical to Unix. We will make all improvements that are convenient, based on our experience with other operating systems. In particular, we plan to have longer file names, file version numbers, a crashproof file system, file name completion perhaps, terminal- independent display support, and perhaps eventually a Lisp-based window system through which several Lisp programs and ordinary Unix programs can share a screen. Both C and Lisp will be available as system programming languages. We will try to support UUCP, MIT Chaosnet, and Internet protocols for communication.

GNU is aimed initially at machines in the 68000/16000 class with virtual memory, because they are the easiest machines to make it run on. The extra effort to make it run on smaller machines will be left to someone who wants to use it on

them.

To avoid horrible confusion, please pronounce the ‘G’ in the word ‘GNU’ when it is the name of this project.

Why I Must Write GNU

I consider that the golden rule requires that if I like a program I must share it with other people who like it. Software sellers want to divide the users and conquer them, making each user agree not to share with others. I refuse to break solidarity with other users in this way. I cannot in good conscience sign a nondisclosure agreement or a software license agreement. For years I worked within the Artificial Intelligence Lab to resist such tendencies and other inhospitalities, but eventually they had gone too far: I could not remain in an institution where such things are done for me against my will.

So that I can continue to use computers without dishonor, I have decided to put together a sufficient body of free software so that I will be able to get along without any software that is not free. I have resigned from the AI lab to deny MIT any legal excuse to prevent me from giving GNU away.