Library:Class Struggle in Africa: Difference between revisions

More languages

More actions

Verda.Majo (talk | contribs) (Added another chapter, added an image, added links) Tag: Visual edit |

Verda.Majo (talk | contribs) (→Intelligentsia and Intellectuals: added ch 6) Tag: Visual edit |

||

| Line 153: | Line 153: | ||

==Elitism== | ==Elitism== | ||

Elitism is an ideology of the bourgeoisie. It arose during the second half of the nineteenth century | Elitism is an ideology of the bourgeoisie. It arose during the second half of the nineteenth century largely as a result of the work of two Italian sociologists, Vilfredo Pareto (1848-1923) and Gaetano Mosca (1858-1941). They wrote at a time when the middle class, which had recently gained political power from the aristocracy, felt in its turn threatened from below by a rapidly growing working class imbued with Marxist ideology. Pareto and Mosca aimed to refute Marx and to deny the possibility of socialist revolution leading to a classless society. Unlike Marx, they maintained that political skill determined who ruled, and that society would always be by some kind of elite, or a combination of elites. | ||

In essence, elitists assert that in practice the minority always exercises effective power, and that the dominant minority never be controlled by the majority, no matter what so-called democratic institutions are employed. The cohesiveness of elites constitute their main strength. They are small in relation to the nation as a whole, but they are strong out of proportion to their size. | In essence, elitists assert that in practice the minority always exercises effective power, and that the dominant minority never be controlled by the majority, no matter what so-called democratic institutions are employed. The cohesiveness of elites constitute their main strength. They are small in relation to the nation as a whole, but they are strong out of proportion to their size. | ||

| Line 200: | Line 200: | ||

==Intelligentsia and Intellectuals== | ==Intelligentsia and Intellectuals== | ||

Under colonialism, an intelligentsia educated in western ideology emerged and provided a link between the colonial power and the masses. It was drawn for the most part from the families of chiefs and from the "moneyed" sections of the population. The growth of the intelligentsia was limited to the minimum needed for the functioning of the colonial administration. It became socially alienated, an elite susceptible both to Left and Right opportunism. | |||

In Africa, as in Europe and elsewhere, education largely determines class. As literacy increases, tribal and ethnic allegiances weaken, and class divisions sharpen. There is what may be described as an ''esprit de corps'', particularly among those who have travelled abroad for their education. They become alienated from tribal and village roots, and in general, their aims are political power, social position, and professional status. Even today, when many independent states have built excellent schools, colleges and universities, thousands of Africans prefer to study abroad. There are at present, some 10,000 African students in France, 10,000 in Britain, and 2,000 in the U.S.A. | |||

In areas of Africa which were once ruled by the British, English type public schools were introduced during the colonial period. In Ghana, Adisadel, Mfantsipim and Achimota are typical examples. In these schools, and in similar schools built throughout British colonies in Africa, curriculum, discipline and sports were as close imitations as possible of those operating in English public schools. The object was to train up a western-oriented political elite committed to the attitudes and ideologies of capitalism and bourgeois society. | |||

In Britain, the English class system is largely based on education. The three per cent products of English public schools are still considered by many to be the country's "natural rulers"—that is, those best qualified to rule both both by birth and education. For in Britain, the educational structure is inseparable from the political and social framework. While only six per cent of the population attends public schools, and only five per cent go to university, the public schools provide 60 per cent of the nation's company directors, 70 per cent of Conservative members of Parliament, and 50 per cent of those appointed to Royal Commissions and public inquiries. In other words, the small minority of products of exclusive educational establishments, occupy the large majority of top positions in the economic and political life of the country. This irrational and outdated "system" still continues to operate in spite of apparent efforts to widen and popularise educational opportunities. It has not yet been seriously challenged by the growing importance of the experts or technocrats, most of them educated in grammar and comprehensive schools. Nor has it shown any significant weakening in the face of growing political pressure from below. In fact, if they could afford it, the majority of working-class parents would send their children to public schools because of the unique opportunities they provide for entry into top positions in society. | |||

The products of English public schools have their counterparts in the British ex-colonial territories. These are the bourgeois establishment figures who try to be more British than the British, and who imitate the dress, manners and even the voices of the British public school and Oxbridge elite. | |||

The colonialists' aim in fostering the growth of an African intelligentsia is "to form local cadres called upon to become our assistants in all fields, and to ensure the development of a carefully selected elite". This, to them, is a political and economic necessity. And how do they do it? "We pick our pupils primarily from among the children of chiefs and aristocrats. . . . The prestige due to origin should be backed up by respect which possession of knowledge evokes." | |||

In 1953, before Ghana’s independence, out of a total of 208 students at the University college, 12 per cent of the families of students had an income of over £600 a year; 38 per cent between £250 and £600; and 50 per cent about £250. The significance of these figures is seen when it is realised that it was only in 1962, after vigorous efforts in the economic field, that it was possible to get the average annual income per head of the population up to approximately £94. | |||

Unlike the British and the French, the Belgians were against allowing the growth of an intelligentsia. "No elite, no trouble" appeared to be their motto. The results of such a policy were clearly seen in the Congo, for example, in 1960 when there was scarcely a qualified Congolese in the country to run the newly-independent state, to officer the army and police, or to fill the many administrative and technical posts left by the departing colonialists. | |||

The intelligentsia always leads the nationalist movement in its early stages. It aspires to replace the colonial power, but not to bring about a radical transformation of society. The object is to control the ‘‘system” rather than to change it, since the intelligentsia tends as a whole to be bourgeois-minded and against revolutionary socialist transformation. | |||

The cohesiveness of the intelligentsia before independence disappears once independence is achieved. It divides roughly into three main groups. First, there are those who support the new privileged indigenous class—the bureaucratic, political and business bourgeoisie who are the open allies of imperialism and neocolonialism. These members of the intelligentsia produce the ideologists of anti-socialism and anti-communism and of capitalist political and economic values and concepts. | |||

Secondly, there are those who advocate a "'non-capitalist road” of economic development, a “mixed economy”, for the less industrialised areas of the world, as a phase in the progress towards socialism. This concept, if misunderstood and misapplied, can probably be more dangerous to the socialist revolutionary cause in Africa than the former open pro-capitalism, since it may seem to promote socialism, whereas in fact it may retard the process. History has proved, and is still proving, that a non-capitalist road, unless it is treated as a very temporary phase in the progress towards socialism, positively hinders its growth. By allowing capitalism and private enterprise to exist in a state committed to socialism, the seeds of a reactionary seizure of power may be sown. The private sector of the economy continually tries to expand beyond the limits within which it is confined, and works ceaselessly to curb and undermine the socialist policies of the socialist-oriented government. Eventually, more often than not, if all else fails, it succeeds, with the help of neocolonialists, in organising a reactionary coup d’état to oust the socialist-oriented government. | |||

The third section of the intelligentsia to emerge after independence consists of the revolutionary intellectuals—those who provide the impetus and leadership of the worker-peasant struggle for all-out socialism. It is from among this section that the genuine intellectuals of the African Revolution are to be found. Very often they are minority products of colonial educational establishments who reacted strongly against its brainwashing processes and who became genuine socialist and African nationalist revolutionaries. It is the task of this third section of the intelligentsia to enunciate and promulgate African revolutionary socialist objectives, and to expose and refute the deluge of capitalist propaganda and bogus concepts and theories poured out by the imperialist, neocolonialist and indigenous, reactionary mass communications media. | |||

Under conditions of capitalism and neocolonialism, the majority of students, teachers, university staff and others coming under the broad category of “intellectuals”, are an elite within the bourgeoisie, and can become a revolutionary or a counter-revolutionary force for political action. Before independence, many of them become leaders of the nationalist revolution. After indepéndence,they tend to split up. Those who helped in the nationalist revolutionary struggle take part in the government, and are oriented either to the Party nouveaux riches, or to the socialist revolutionaries. The others join the political opposition, or become apolitical, or advocate middle of the road policies. Some become dishonest intellectuals. For they see the irrationality of capitalism but enjoy its benefits and way of life; and for their own selfish reasons are prepared to prostitute themselves and become agents and supporters of privilege and reaction. | |||

In general, intellectuals with working-class origins tend to be more radical than those from the privileged sectors of society. But intellectuals are probably the least cohesive or homogeneous of elites. Most of the intellectuals in the U.S.A., Britain and in Western Europe belong to the Right. Similarly, the aspirations of the majority of Africa’s intellectuals are characteristic of the middle class. They seek power, prestige, wealth and social position for themselves and their families. Many of those from working-class families aspire to middleclass status, shrinking from manual work and becoming completely alienated from their class and social origins. | |||

Where socialist revolutionary intellectuals have become part of genuinely progressive administrations in Africa, it has usually been through the adoption of Marxism as a political creed, and the formation of Communist parties or similar organisations which bring them into constant close contact with workers and peasants. | |||

Intelligentsia and intellectuals, if they are to play a part in the African Revolution, must become conscious of the class struggle in Africa, and align themselves with the oppressed masses. This involves the difficult, but not impossible, task of cutting themselves free from bourgeois attitudes and ideologies imbibed as a result of colonialist education and propaganda. | |||

The ideology of the African Revolution links the class struggle of African workers and peasants with world socialist revolutionary movements and with international socialism. It emerged during the national liberation struggle, and it continues to mature in the fight to complete the liberation of the continent, to achieve political unification, and to effect a socialist transformation of African society.-It is unique. It has developed within the concrete situation of the African Revolution, is a product of the African Personality, and at the same time is based on the principles of scientific socialism. | |||

==Reactionary Cliques among Armed Forces and Police== | ==Reactionary Cliques among Armed Forces and Police== | ||

==Coups d’état== | ==Coups d’état== | ||

Revision as of 11:48, 19 May 2024

Class Struggle in Africa | |

|---|---|

| Author | Kwame Nkrumah |

| Publisher | International Publishers |

| First published | 1970 New York |

| Type | Book |

| Source | archive.org |

Dedication

This book is dedicated to the workers and peasants of Africa.

Introduction

In Africa where so many different kinds of political, social and economic conditions exist it is not an easy task to generalise on political and socio-economic patterns. Remnants of communalism and feudalism still remain and in parts of the continent ways of life have changed very little from traditional times. In other areas a high level of industrialisation and urbanisation has been achieved. Yet in spite of Africa’s socio-economic and political diversity it is possible to discern certain common political, social and economic conditions and problems. These derive from traditional past, common aspirations, and from shared experience under imperialism, colonialism and neocolonialism. There is no part of the continent which has not known oppression and exploitation, and no part which remains outside the processes of the African Revolution. Everywhere, the underlying unity of purpose of the peoples of Africa is becoming increasingly evident, and no African leader can survive who does not pay at least lip service to the African revolutionary objectives of total liberation, unification and socialism.

In this situation, the ground is well prepared for the next crucial phase of the Revolution, when the armed struggle which has now emerged must be intensified, expanded and effectively co-ordinated at strategic and tactical levels; and at the same time, a determined attack must be made on the entrenched position of the minority reactionary elements amongst our own peoples. For the dramatic exposure in recent years of the nature and extent of the class struggle in Africa, through the succession of reactionary military coups and the outbreak of civil wars, particularly in West and Central Africa, has demonstrated the unity between the interests of neo-colonialism and the indigenous bourgeoisie.

At the core of the problem is the class struggle. For too long, social and political commentators have talked and written as though Africa lies outside the main stream of world historical development—a separate entity to which the social, economic and political patterns of the world do not apply. Myths such as "African socialism" and "pragmatic socialism", implying the existence of a brand or brands of socialism applicable to Africa alone, have been propagated; and much of our history has been written in terms of socio-anthropological and historical theories as though Africa had no history prior to the colonial period. One of these distortions has been the suggestion that the class structures which exist in other parts of the world do not exist in Africa.

Nothing is further from the truth. A fierce class struggle has been raging in Africa. The evidence is all around us. In essence it is, as in the rest of the world, a struggle between the oppressors and the oppressed.

The African Revolution is an integral part of the world socialist revolution, and just as the class struggle is basic to world revolutionary processes, so also is it fundamental to the struggle of the workers and peasants of Africa.

Class divisions in modern African society became blurred to some extent during the pre-independence period, when it seemed there was national unity and all classes joined forces to eject the colonial power. This led some to proclaim that there were no class divisions in Africa, and that the communalism and egalitarianism of traditional African society made any notion of a class struggle out of the question. But the exposure of this fallacy followed quickly after independence, when class cleavages which had been temporarily submerged in the struggle to win political freedom reappeared, often with increased intensity, particularly in those states where the newly independent government embarked on socialist policies.

For the African bourgeoisie, the class which thrived under colonialism, is the same class which is benefiting under the post-independence, neocolonial period. Its basic interest lies in preserving capitalist social and economic structures. It is therefore, in alliance with international monopoly finance capital

[Image, p. 11: The privileged and the oppressed under colonialism and neocolonialism]

and neocolonialism, and in direct conflict with the African masses, whose aspirations can only be fulfilled through scientific socialism.

Although the African bourgeoisie is small numerically, and lacks the financial and political strength of its counterparts in the highly industrialised countries, it gives the illusion of being economically strong because of its close tie-up with foreign finance capital and business interests. Many members of the African bourgeoisie are employed by foreign firms and have, therefore, a direct financial stake in the continuance of the foreign economic exploitation of Africa. Others, notably in the civil service, trading and mining firms, the armed forces, the police and in the professions, are committed to capitalism because of their background, their western education, and their shared experience and enjoyment of positions of privilege. They are mesmerised by capitalist institutions and organisations. They ape the way of life of their old colonial masters, and are determined to preserve the status and power inherited from them.

Africa has in fact in its midst a hard core of bourgeoisie who are analogous to colonists and settlers in that they live in positions of privilege—a small, selfish, money-minded, reactionary minority among vast masses of exploited and oppressed people. Although apparently strong because of their support from neocolonialists and imperialists, they are extremely vulnerable. Their survival depends on foreign support. Once this vital link is broken, they become powerless to maintain their positions and privileges. They and the "hidden hand" of neo-colonialism and imperialism which supports and abets reaction and exploitation now tremble before the rising tide of worker and peasant awareness of the class struggle in Africa.

Origins of Class in Africa

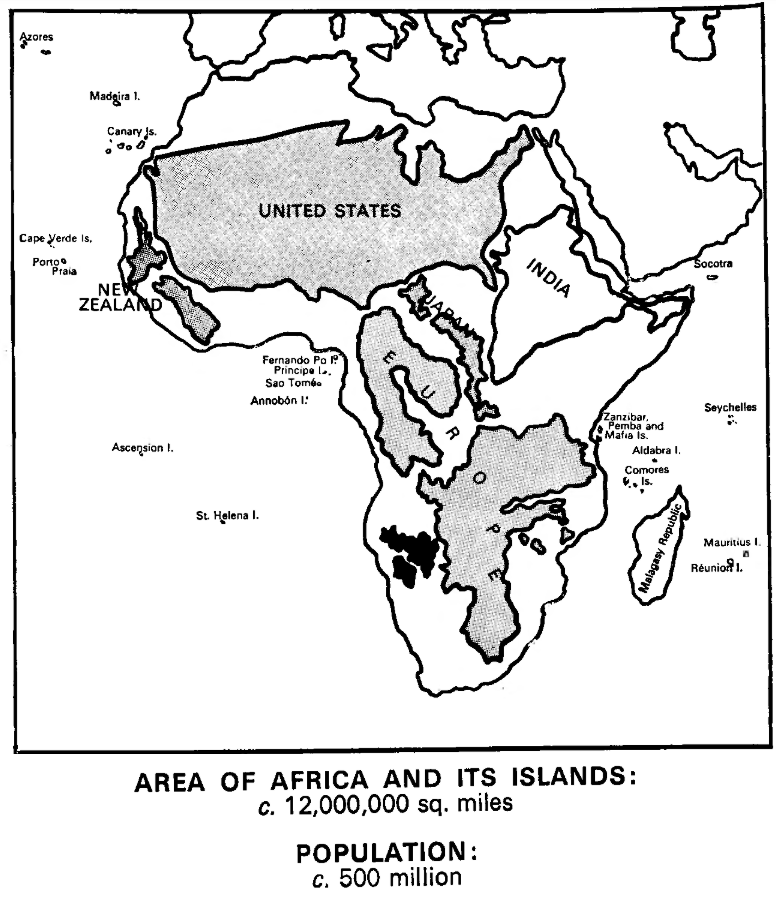

Africa and its islands, with a land area of some twelve million square miles and a population estimated at about 500 million, could easily contain within it, and with room to spare, the whole of India, Europe, Japan, the British Isles, Scandinavia and New Zealand. The United States of America could easily be fitted into the Sahara Desert. Africa is geographically compact, and in terms of natural resources potentially the richest continent in the world.

In Africa, where economic development is uneven, a wide variety of highly sophisticated political systems were in existence over many centuries before the colonial period began. It is here, in the so-called developing world of Africa, and in Asia and Latin America, where the class struggle and the progress towards ending the exploitation of man by man have already entered into the stage of decisive revolutionary change.

The political maturity of the African masses may to some extent be traced to economic and social patterns of traditional times. Under communalism, for example, all land and means of production belonged to the community. There was people’s ownership. Labour was the need and habit of all. When a certain piece of land was allocated to an individual for his personal use, he was not free to do as he liked with it since it still belonged to the community. Chiefs were strictly controlled by counsellors and were removable.

There have been five major types of production relationships known to man—communalism, slavery, feudalism, capitalism and socialism. With the establishment of the socialist state, man has embarked on the road to communism. It was when private property relationships emerged, and as communalism gave way to slavery and feudalism, that the class struggle began.

In general, at the opening of the colonial period, the peoples of Africa were passing through the higher stage of communalism characterised by the disintegration of tribal democracy and the emergence of feudal relationships, hereditary tribal chieftaincies and monarchical systems. With the impact of imperialism and colonialism, communalist socio-economic patterns began to collapse as a result of the introduction of export crops such as cocoa and coffee. The economies of the colonies became interconnected with world capitalist markets. Capitalism, individualism, and tendencies to private ownership grew. Gradually, primitive communalism disintegrated and the collective spirit declined. There was an expansion of private farming and the method of small commodity production.

It was a relatively easy matter for white settlers to appropriate land which was not individually owned. For example, in Malawi, by 1892, more than sixteen per cent of the land had been alienated, and three quarters of it was under the direction of eleven big companies. When the land was seized by settlers, the African "owners" became in some cases tenants or lease-holders, but only on land considered not fertile enough for white farmers. The latter were usually issued with certificates of ownership of land by the British consul, acting on behalf of the British government; and any land not under any specific private ownership was declared "British crown land". Similar arrangements were made in other parts of colonial Africa.

Under colonialism, communal ownership of land was finally abolished and ownership of land imposed by law. Furthermore, through the system of "Indirect Rule", chiefs became tools, and in many cases paid agents, of the colonial administration.

With the seizure of the land, with all its natural resources—that is, the means of production, two sectors of the economy emerged—the European and the African, the former exploiting the latter. Subsistence agriculture was gradually destroyed and Africans were compelled to sell their labour power to the colonialists, who turned their profits into capital. It was in these circumstances that the race-class struggle also emerged as part of the class struggle.

With the growth of commodity production, mainly for export, single crop economies developed completely dependent on foreign capital. The colony became a sphere for investment and exploitation. Capitalism developed with colonialism. At the same time, the spread of private enterprise, together with the needs of the colonial administrative apparatus, resulted in the emergence of first a petty bourgeois class and then an urban bourgeois class of bureaucrats, reactionary intellectuals, traders, and others, who became increasingly part and parcel of the colonial economic and social structure.

To facilitate exploitation, colonialism hampered social and cultural progress in the colonies. Obsolete forms of social relations were restored and preserved. Capitalist methods of production, and capitalist social relationships were introduced. Friction between tribes was in some cases deliberately encouraged when it served to strengthen the hands of colonial administrators.

But certain economic developments, such as that of the extractive industry, plantations and capitalist farming, the building of ports, roads and railways was undertaken in the interests of capitalism. As a result, social changes occurred. Feudal and semi-feudal relationships were undermined with the emergence of an industrial and agricultural proletariat. At the same time there developed a national bourgeoisie and an intelligentsia.

In this colonialist situation, African workers regarded the colonialists, foreign firms and foreign planters, as the exploiters. Thus their class struggle became in the first instance anti-imperialist, and not directed against the indigenous bourgeoisie. It is this which has been responsible in some degree for the relatively slow awakening of the African worker and peasant to the existence of their true class enemy—the indigenous bourgeoisie.

At the end of the colonial period there was in most African states a highly developed state machine and a veneer of Parliamentary democracy concealing a coercive state run by an elite of bureaucrats with practically unlimited power. There was an intelligentsia, completely indoctrinated with western values; a virtually non-existent labour movement; a professional army and a police force with an officer corps largely trained in western military academies; and a chieftaincy used to administering at local level on behalf of the colonial government.

But on the credit side, a new grass roots political leadership emerged during the independence struggle. This was based on worker and peasant support, and committed not only to the winning of political freedom but to a complete transformation of society. This revolutionary leadership, although of necessity associated with the national bourgeoisie in the independence struggle was quite separate from it, and proceeded to break away after independence to pursue its class socialist objectives. This struggle still continues.

Class Concept

Class struggle is a fundamental theme of recorded history. In every non-socialist society there are two main categories of class, the ruling class or classes, and the subject class or classes. The ruling class possesses the major instruments of economic production and distribution, and the means of establishing its political dominance, while the subject class serves the interests of the ruling class, and is politically, economically and socially dominated by it. There is conflict between the ruling class and the exploited class. The nature and cause of the conflict is influenced by the development of productive forces. That is, in any given class formation, whether it be feudalism, capitalism, or any other type of society, the institutions and ideas associated with it arise from the level of productive forces and the mode of production. The moment private ownership of the means of production appears, and capitalists start exploiting workers the capitalists become a bourgeois class, the exploited workers a working class. For in the final analysis, a class is nothing more than the sum total of individuals bound together by certain interests which as a class they try to preserve and protect.

Every form of political power, whether parliamentary, multi-party, one-party or open military dictatorship, reflects the interest of a certain class or classes in society. In socialist states the government represents workers and peasants. In capitalist states, the government represents the exploiting class, The state then, is the expression of the domination of one class over other classes.

Similarly, political parties represent the existence of different classes. It might be assumed from this that a single party state denotes classlessness. But this is not necessarily the case. It only applies if the state represents political power held by the people. In many states, where two or more political parties exist, and where there are sharp class cleavages, there is to all intents and purposes government by a single party. In the case of the United States of America, for example, Republican and Democratic Parties may be said to be in fact a single party in

[Image, p. 18: Class struggle]

that they represent a single class, the propertied class. In Britain, there is in practice little difference between the Conservative Party and the Labour Party. The Labour Party founded to promote the interests of the working class has in fact developed into a bourgeois oriented party. Both the Conservative Party and the Labour Party are therefore expressions of the bourgeoisie and reflect its ideology.

Inequality can only be ended by the abolition of classes. The division between those who plan, organise and manage, and those who actually perform the manual labour, continually recreates the class system. The individual usually finds it very difficult, if not impossible, to break out of the sphere of life into which he is born; and even where there is "equality of opportunity", the underlying assumption of inequality remains, where the purpose of "opportunity" is to aspire to a higher level in a stratified society.

A ruling class is cohesive and conscious of itself as a class. It has objective interests, is aware of its position and the threat posed to its continued dominance by the rising tide of working class revolt. In Africa, the ruling classes account for approximately only one per cent of the population. Some 80-90 per cent of the population consists of peasants and agricultural labourers. Urban and industrial workers represent about five per cent. Yet because of the presence of foreigners and foreign interests, class struggle in African society has been blurred. Conflict between the African peoples and the interests of neo-colonialism, colonialism, imperialism and settler regimes, has concealed all other contradictory forces. This explains to some extent why class or vanguard parties have been so long emerging in Africa.

Broadly, the existing class pattern of African society may be shown as follows:

[Table on p. 19-20]

The uneven economic development of Africa has made for a variety of class patterns with wide differences existing between the areas of white settler minority governments, the few remaining colonial enclaves, and independent Africa.

For example, in Rhodesia, four million Africans are crowded into less than half the land acreage of the country. In other words, more than half the land is in the hands of some 500,000 white settlers. This state of affairs has resulted in an enormous social and political gulf between the rich, white estate owners and the impoverished politically-impotent African peasants and workers. Here, as in all settler areas, class is a race issue first and foremost—the "haves" are white, the "have-nots" are black—and all the usual arguments—the myth of racial inferiority, the need for government by the most able, and so on—are used to justify perpetuation of the enforced, racialist, settler arrangement.

Again, in francophone Africa, social patterns have resulted in the emergence of class divisions peculiar to this particular colonised area. There were the "citoyens", the French "colons" or citizens. There were the "assimilés", the coloured mulattoes and the black intelligentsia, or those Africans who worked their way to this class through the Army or the bureaucracy. Then came the "sujets", the workers and peasants. An "'assimilé" could become a "citoyen", but a "sujet" could not, unless he first worked his way into the "'assimilé" class. This type of social system operated in all the French colonies. Analogous arrangements still exist in the few remaining Spanish and Portuguese territories in Africa.

The assimilation policy meant that any colonial "'subject"’ could be naturalised as a full French citizen. In practice, however, even those who reached a high enough level of education usually did not attempt to avail themselves of this so-called privilege, largely because, except in the Four Communes, French citizenship was incompatible with the retention of one’s personal status—that is, the right to live by African customary law as opposed to the French code civil. There was a certain logic in this from a strictly assimilationist point of view: if one was going to be a Frenchman in the political sense, then one should behave like one socially, and accept such institutions as monogamy and French inheritance laws. But its effect underlined the failure of assimilation, for on these terms, assimilation was not a saleable commodity; and so, outside the Four Communes, "citizen" remained virtually synonymous with "white Frenchman".

While the nature of the economic relationship between the colony and its metropolitan master determined the nature of the class conflict in a particular area, other factors included the ideas and customs of the invading power, although these were attributable ultimately to changes in the structure of productive relations.

In areas colonised by the British, a certain amount of urbanisation made for the emergence of bourgeois and petty bourgeois elites which developed their own class characteristic attitudes and organisations. To obtain a "white collar" job became the ambition of every African aspiring to improve his prospects and social status. Manual work, particularly agricultural work, was considered beneath the dignity of anyone who had acquired even the most rudimentary degree of education.

In pre-colonial Africa, under conditions of communalism, slavery and feudalism there were embryonic class cleavages. But it was not until the era of colonial conquest that a Europeanised class structure began to develop with clearly identifiable classes of proletariat and bourgeoisie. This development has always been played down by reactionary observers, most of whom have maintained that African societies are homogeneous and without class divisions. They have even endeavoured to retain this view in the face of glaring evidence of class struggle shown in the post-independence period, when bourgeois elements have joined openly with neocolonialists, colonialists and imperialists in vain attempts to keep the African masses in permanent subjection.

Class Characteristics and Ideologies

There is a close connection between socio-political development, the struggle between social classes and the history of ideologies. In general, intellectual movements closely reflect the trends of economic developments. In communal society, where there are virtually no class divisions, man's productive activities exert a direct influence on his outlook and aesthetic tastes. But in a class society, the direct influence of productive activities on outlook and culture is less discernible. Account must be taken of the psychology of conflicting classes.

Certain social habits, dress, institutions and organisations are associated with different classes. It is possible to place a person in a particular class simply by observing his general appearance, his dress and the way he behaves. Similarly, each class has its own characteristic institutions and organisations. For example, co-operatives and trade unions are organisations of the working class. Professional associations, chambers of commerce, stock exchanges, rotary clubs, masonic societies, and so on, are middle class, bourgeois institutions.

Ideologies reflect class interests and class consciousness. Liberalism, individualism, elitism, and bourgeois ''democracy"—which is an illusion—are examples of bourgeois ideology. Fascism, imperialism, colonialism, and neocolonialism are also expressions of bourgeois thinking and of bourgeois political and economic aspirations. On the other hand, socialism and communism are ideologies of the working class, and reflect its aspirations and politico-economic institutions and organisations.

The bourgeois conception of freedom as the absence of restraint, of laissez-faire, free enterprise, and of "every man for himself", is a typical expression of bourgeois ideology. The basic thesis is that the purpose of government is to protect private property and the private ownership of the means of production and distribution. Freedom is confined to the political sphere, and has no relevance to economic matters. Capitalism, which knows no law beyond its own interest, is equated

[Image on p. 24, bourgeois ideas]

with economic freedom. Inseparable from this conception of freedom is the view that the presence or absence of wealth denotes the presence or absence of ability.

Coupled with the bourgeois conception of freedom is the bourgeois worship of "law and order" regardless of who made the law, or of whether it serves the interests of the people, a class or of a narrow elite.

In recent years, in the face of growing revolutionary violence throughout the world, new misleading bourgeois terminology has emerged which expresses the reactionary back-lash. Typical examples are the myths of the "silent majority" or the "average" or "ordinary citizen", both of which are said to be anti-revolutionary and in favour of maintaining the status quo. In fact, in any capitalist society, the working class forms the majority and this class is far from silent, and is vocal in its demand for a radical transformation of society.

In Africa, the African bourgeoisie, anxious to emulate European middle class attitudes and ideologies, have in many cases confused class with race. They find it difficult to differentiate between European classes since they are not familiar with the subtle differences in speech, manners, dress and so on—differences which would instantly betray their class origin to their own fellow countrymen. Members of the European working class live as bourgeoisie in the colonies. They own cars, have servants, their women do not enter the kitchen, and their class origin is only apparent to their own people. After independence, the indigenous bourgeoisie, in aspiring to ruling class status, copy the way of life of the ex-ruling class—the Europeans. They are, in reality, imitating a race and not a class.

The African bourgeoisie, therefore, tends to live the kind of life lived by the old colonial ruling class, which is not necessarily the way of life of the European bourgeoisie. It is rather the way of life of a racial group in a colonial situation. In this sense, the African bourgeoisie perpetuates the master-servant relationships of the colonial period.

Although the African bourgeoisie for the most part slavishly accepts the ideologies of its counterparts in the capitalist world, there are certain ideologies which have developed specifically within the African context, and which have become characteristic expressions of African bourgeois mentality. Perhaps the most typical is the bogus conception of "'negritude". This pseudo-intellectual theory serves as a bridge between the African foreign-dominated middle class and the French cultural establishment. It is irrational, racist and non-revolutionary. It reflects the confused state of mind of some of the colonised French African intellectuals, and is totally divorced from the reality of the African Personality.

The term "African socialism" is similarly meaningless and irrelevant. It implies the existence of a form of socialism peculiar to Africa and derived from communal and egalitarian aspects of traditional African society. The myth of African socialism is used to deny the class struggle, and to obscure genuine socialist commitment. It is employed by those African leaders who are compelled—in the climate of the African Revolution—to proclaim socialist policies, but who are at the same time deeply committed to international capitalism, and who do not intend to promote genuine socialist economic development.

While there is no hard and fast dogma for socialist revolution, and specific circumstances at a definite historical period will determine the precise form it will take, there can be no compromise over socialist goals. The principles of scientific socialism are universal and abiding, and involve the genuine socialisation of productive and distributive processes. Those who for political reasons pay lip service to socialism, while aiding and abetting imperialism and neocolonialism, serve bourgeois class interests. Workers and peasants may be misled for a time, but as class consciousness develops the bogus socialists are exposed, and genuine socialist revolution is made possible.

Class and Race

Each historical situation develops its own dynamics. The close links between class and race developed in Africa alongside capitalist exploitation. Slavery, the master-servant relationship, and cheap labour were basic to it. The classic example is South Africa, where Africans experience a double exploitation—both on the ground of colour and of class. Similar conditions exist in the U.S.A., the Caribbean, in Latin America, and in other parts of the world where the nature of the development of productive forces has resulted in a racist class structure. In these areas, even shades of colour count—the degree of blackness being a yardstick by which social status is measured.

While a racist social structure is not inherent in the colonial situation, it is inseparable from capitalist economic development. For race is inextricably linked with class exploitation; in a racist-capitalist power structure, capitalist exploitation and race oppression are complementary; the removal of one ensures the removal of the other.

In the modern world, the race struggle has become part of the class struggle. In other words, wherever there is a race problem it has become linked with the class struggle.

The effects of industrialisation in Africa as elsewhere, has been to foster the growth of the bourgeoisie, and at the same time the growth of a politically-conscious proletariat. The acquisition of property and political power on the part of the bourgeoisie, and the growing socialist and African nationalist aspirations of the working class, both strike at the root of the racist class structure, though each is aiming at different objectives.

The bourgeoisie supports capitalist development while the proletariat—the oppressed class—is striving towards socialism.

In South Africa, where the basis of ethnic relationships is class and colour, the bourgeoisie comprises about one fifth of the population. The British and the Boers, having joined forces

[Image, p. 28: Capital class relationships and racialism; double exploitation]

to maintain their positions of privilege, have split up the remaining four-fifths of the population into "Blacks", "Coloureds" and "Indians". The Coloureds and Indians are minority groups which act as buffers to protect the minority Whites against the increasingly militant and revolutionary Black majority. In the other settler areas of Africa, a similar classs-race struggle is being waged.

A non-racial society can only be achieved by socialist revolutionary action of the masses. It will never come as a gift from the minority ruling class. For it is impossible to separate race relations from the capitalist class relationships in which they have their roots.

South Africa again provides a typical example. In the early years of Dutch settlement, the distinction was made not between Black and White, but between Christian and Heathen. It was only with capitalist economic penetration that the master-servant relationship emerged, and with it, racism, colour prejudice and apartheid. The latter is the most intolerable and iniquitous of policies and race-class "systems" ever to emerge from White, capitalist, bourgeois society. Eighty per cent of the population of South Africa is non-white and has no vote or political rights.

Slavery and the master-servant relationship were therefore the cause, rather than the result of, racism. The position was crystallized and reinforced with the discovery of gold and diamonds in South Africa, and the employment of cheap African labour in the mines. As time passed, and it was thought necessary to justify the exploitation and oppression of African workers, the myth of racial inferiority was developed and spread.

In the era of neocolonialism, "under-development" is still attributed not to exploitation but to inferiority, and racial undertones remain closely interwoven with the class struggle.

It is only the ending of capitalism, colonialism, imperialism and neocolonialism and the attainment of world communism that can provide the conditions under which the race question can finally be abolished and eliminated.

Elitism

Elitism is an ideology of the bourgeoisie. It arose during the second half of the nineteenth century largely as a result of the work of two Italian sociologists, Vilfredo Pareto (1848-1923) and Gaetano Mosca (1858-1941). They wrote at a time when the middle class, which had recently gained political power from the aristocracy, felt in its turn threatened from below by a rapidly growing working class imbued with Marxist ideology. Pareto and Mosca aimed to refute Marx and to deny the possibility of socialist revolution leading to a classless society. Unlike Marx, they maintained that political skill determined who ruled, and that society would always be by some kind of elite, or a combination of elites.

In essence, elitists assert that in practice the minority always exercises effective power, and that the dominant minority never be controlled by the majority, no matter what so-called democratic institutions are employed. The cohesiveness of elites constitute their main strength. They are small in relation to the nation as a whole, but they are strong out of proportion to their size.

Elitism is an ideology tailor-made to fit capitalism and bourgeois de facto domination in the capitalist society. Furthermore, it intensifies racism, since it can be used to subscribe to the myth of racial superiority and inferiority.

In recent times, there has been a great revival of interest in the study of elites, and many new elitist theories have been disseminated. It is significant that this development coincides historically with a tremendous upsurge of socialist revolutionary activity in the world. Bourgeois theorists, seeking to justify the continuance of capitalism, have found it necessary to fall back on elitism. They cannot by any rational argument justify the harsh irrationality of capitalism. So they try to show that there wil always be a ruling elite, and that government is always in the hands of those most fitted to govern. In maintaining this, they evade the reality of the economic class structure and class struggle in capitalist society.

Among the basic tenets of elitism is the theory that power breeds power, and that apathy, submissiveness and deference are qualities of the masses in politics. Democracy has been defined as competition between oligarchies. It has become fashionable to talk of top decision-makers, and to discuss which group or groups really wield power in a state. Is there a concentration or a diffusion of power? How are political decisions made? Are they made by a ruling elite? Do the masses exercise any measure of indirect power? Or are decisions made by diverse elite groupings? Is it true that: "Governments do not govern, but merely control the machinery of government, being themselves controlled by the hidden hand"?

Pluralists assert that power is not held by a single elite, but by a mixture of many. Power is regarded as cumulative—wealth, social status, and political power being inter- woven. Connected with this view is the idea of "elite consensus"—that is, the involvement in policy formation of only the most important elite groupings.

It was one of the declared aims of the early elitists to demolish the myths of "democracy". They set out to show that in so-called democracies, the people, or a majority of the people do not in fact rule, but that government is carried out by a narrow elite. They went even further and asserted that participation in government was not a necessary feature of democracy, and not in itself an important ideal.

There can be no class within a class, but there are elites within a class. Elites arise from the development and formation of a class. In Europe, the broad class pattern is as follows:

Traditional aristocracy — based on land and titles

Middle class — based on money, and divided into upper, middle and lower

Working class — based on agriculture and industry, and divided into upper and lower.

Among the middle class—the new aristocracy—are plutocrats, managers, intellectuals, bureaucrats, technocrats, and so on, each of which may be said to constitute an elite. With the rapid development of technology, and increasing specialisation, the strata of technocrats—an elite within the middle-class—is becoming increasingly influential in decision-making. Some elitists assert that a meritocracy—government by the "expert"—is now a reality.

European-style elites may be discerned among the African bourgeoisie. Under colonialism, the African elites were chiefs in the colonial legislative councils and in the colonial administrative services; lawyers and doctors; judges and magistrates; top civil servants; senior army and police officers. After independence, the old elites remained virtually intact, and acquired greater strength. The position of members of Parliament and National Assemblies, cabinet ministers, top civil servants, senior army and police officers, and so on, were enhanced. They were no longer subordinate to colonial authority. Members of the professions, for example, teachers, lawyers and doctors, benefited by the Africanisation policies of the newly-independent government.

It was in the post-independence period that there emerged what may be termed the "party nouveaux riches", an elite which developed from among the ranks of the Party which successfully won political freedom from the colonial power. After independence, conflict develops within the Party between Right and Left wing elements. The Rightists become the Party nouveaux riches. They proceed to make their fortunes once independence has been achieved, and the Party has become the governing Party. They exploit their new positions of power and indulge in nepotism and corruption, thereby discrediting the Party and helping to pave the way for reactionary coups d'état.

Similarly, after independence, and with the implementation of economic Development Plans, and the encouragement in some cases of indigenous business enterprise, local budding capitalists to some extent acquired new opportunities to extend their interests. But in general, African capitalists are still the junior partners of imperialism. They receive the crumbs of investment profits, commercial agencies, commissions, and directorships of foreign-owned firms. In these, and in many other ways, they are drawn into the web of neocolonialism.

As a result of colonialism and neocolonialism, there has been comparatively little development of an African business elite. In addition, the fact that many newly-independent governments tend to concentrate on the public rather than on the private sector of the economy, has led to the relatively small size of the African capitalist class. The African business man is, in general, not so much interested in developing industry as in seeking to enrich himself by speculation, black marketeering, corruption and the receipt of commissions from contracts, and by various financial manipulations connected ' with the receipt of so-called "aid". The African capitalist thus becomes the class ally of the bourgeoisie of the capitalist world. He is a pawn in the immense network of international monopoly finance capital.

In this way, he is closely connected with, for example, the giant corporations of monopoly capitalism. It has been asserted that in the U.S.A. the "finpols", that is, the financial politicians, exercise decisive power and are responsible for major decision-making. This is done through "finpolities"—huge corporations such as the Ford Motor Company, Du Pont and General Motors—to mention only a few. In 1953 there were more than 27,000 millionaires in the U.S.A., and the concentration of wealth in a few hands is intensifying. It is estimated that 1.6 per cent of the population owns at least 32 per cent of all assets, and nearly all investment assets; and 50 per cent of the population owns practically nothing. It cannot be said that power in the U.S.A. is in the hands of the most qualified, since most of the wealth is inherited, and its possession, therefore, does not necessarily denote merit.

Yet it has been held by some elitists that development of industrial societies can be shown as a movement from a class system to a system of elites based on merit and achievement. Such a theory falls to the ground in the light of clear evidence of the sharpening of class struggle throughout the capitalist world.

Among elitists, opinions differ as to how far elites can be said to be cohesive, conscious, and conspiratorial. Obviously it is impossible to measure precisely the influence and decision-making power, and the degree of cohesiveness of any particular elite or group of elites.

Among the political elite in the developing countries are nationalist leaders, bureaucrats and intelligentsia. Of the members of the Ghana House of Assembly after the 1954 election, 29 per cent were school teachers and 17 per cent were members of the liberal professions. Among the Legislative Assembly members of the eight territories of the former French West Africa, after the 1957 elections, 22 per cent were teachers, 27 per cent were government officials, and 20 per cent were members of the professions.

The middle class in developing countries was in the main created by the educational and administrative systems introduced under colonialism. The predominance of the intelligentsia in the middle class is due in the main to the deliberate policy of the colonial power in fostering the growth of an intelligentsia geared to western ideologies which it needed for the successful functioning of the colonial administration. At the same time the colonial power curbed opportunities for the formation of an indigenous business class.

Elite associations, such as bar associations, medical societies, oddfellows, freemasonry, rotary clubs, etc., emerge with the development of elites. These associations assist class formation by institutionalising social differences. The existence of class feeling is shown in the desire to join associations and clubs which are thought to enhance social status.

Elitism is basic to the thinking of those who accept class stratification. It is an ingredient of capitalism, and is further intensified by racism, which in its turn is a result of the growth of capitalism and imperialism. The inherent elitism of the ruling classes makes them contemptuous of the masses. Elitism is an enemy of socialism and of the working class.

Intelligentsia and Intellectuals

Under colonialism, an intelligentsia educated in western ideology emerged and provided a link between the colonial power and the masses. It was drawn for the most part from the families of chiefs and from the "moneyed" sections of the population. The growth of the intelligentsia was limited to the minimum needed for the functioning of the colonial administration. It became socially alienated, an elite susceptible both to Left and Right opportunism.

In Africa, as in Europe and elsewhere, education largely determines class. As literacy increases, tribal and ethnic allegiances weaken, and class divisions sharpen. There is what may be described as an esprit de corps, particularly among those who have travelled abroad for their education. They become alienated from tribal and village roots, and in general, their aims are political power, social position, and professional status. Even today, when many independent states have built excellent schools, colleges and universities, thousands of Africans prefer to study abroad. There are at present, some 10,000 African students in France, 10,000 in Britain, and 2,000 in the U.S.A.

In areas of Africa which were once ruled by the British, English type public schools were introduced during the colonial period. In Ghana, Adisadel, Mfantsipim and Achimota are typical examples. In these schools, and in similar schools built throughout British colonies in Africa, curriculum, discipline and sports were as close imitations as possible of those operating in English public schools. The object was to train up a western-oriented political elite committed to the attitudes and ideologies of capitalism and bourgeois society.

In Britain, the English class system is largely based on education. The three per cent products of English public schools are still considered by many to be the country's "natural rulers"—that is, those best qualified to rule both both by birth and education. For in Britain, the educational structure is inseparable from the political and social framework. While only six per cent of the population attends public schools, and only five per cent go to university, the public schools provide 60 per cent of the nation's company directors, 70 per cent of Conservative members of Parliament, and 50 per cent of those appointed to Royal Commissions and public inquiries. In other words, the small minority of products of exclusive educational establishments, occupy the large majority of top positions in the economic and political life of the country. This irrational and outdated "system" still continues to operate in spite of apparent efforts to widen and popularise educational opportunities. It has not yet been seriously challenged by the growing importance of the experts or technocrats, most of them educated in grammar and comprehensive schools. Nor has it shown any significant weakening in the face of growing political pressure from below. In fact, if they could afford it, the majority of working-class parents would send their children to public schools because of the unique opportunities they provide for entry into top positions in society.

The products of English public schools have their counterparts in the British ex-colonial territories. These are the bourgeois establishment figures who try to be more British than the British, and who imitate the dress, manners and even the voices of the British public school and Oxbridge elite.

The colonialists' aim in fostering the growth of an African intelligentsia is "to form local cadres called upon to become our assistants in all fields, and to ensure the development of a carefully selected elite". This, to them, is a political and economic necessity. And how do they do it? "We pick our pupils primarily from among the children of chiefs and aristocrats. . . . The prestige due to origin should be backed up by respect which possession of knowledge evokes."

In 1953, before Ghana’s independence, out of a total of 208 students at the University college, 12 per cent of the families of students had an income of over £600 a year; 38 per cent between £250 and £600; and 50 per cent about £250. The significance of these figures is seen when it is realised that it was only in 1962, after vigorous efforts in the economic field, that it was possible to get the average annual income per head of the population up to approximately £94.

Unlike the British and the French, the Belgians were against allowing the growth of an intelligentsia. "No elite, no trouble" appeared to be their motto. The results of such a policy were clearly seen in the Congo, for example, in 1960 when there was scarcely a qualified Congolese in the country to run the newly-independent state, to officer the army and police, or to fill the many administrative and technical posts left by the departing colonialists.

The intelligentsia always leads the nationalist movement in its early stages. It aspires to replace the colonial power, but not to bring about a radical transformation of society. The object is to control the ‘‘system” rather than to change it, since the intelligentsia tends as a whole to be bourgeois-minded and against revolutionary socialist transformation.

The cohesiveness of the intelligentsia before independence disappears once independence is achieved. It divides roughly into three main groups. First, there are those who support the new privileged indigenous class—the bureaucratic, political and business bourgeoisie who are the open allies of imperialism and neocolonialism. These members of the intelligentsia produce the ideologists of anti-socialism and anti-communism and of capitalist political and economic values and concepts.

Secondly, there are those who advocate a "'non-capitalist road” of economic development, a “mixed economy”, for the less industrialised areas of the world, as a phase in the progress towards socialism. This concept, if misunderstood and misapplied, can probably be more dangerous to the socialist revolutionary cause in Africa than the former open pro-capitalism, since it may seem to promote socialism, whereas in fact it may retard the process. History has proved, and is still proving, that a non-capitalist road, unless it is treated as a very temporary phase in the progress towards socialism, positively hinders its growth. By allowing capitalism and private enterprise to exist in a state committed to socialism, the seeds of a reactionary seizure of power may be sown. The private sector of the economy continually tries to expand beyond the limits within which it is confined, and works ceaselessly to curb and undermine the socialist policies of the socialist-oriented government. Eventually, more often than not, if all else fails, it succeeds, with the help of neocolonialists, in organising a reactionary coup d’état to oust the socialist-oriented government.

The third section of the intelligentsia to emerge after independence consists of the revolutionary intellectuals—those who provide the impetus and leadership of the worker-peasant struggle for all-out socialism. It is from among this section that the genuine intellectuals of the African Revolution are to be found. Very often they are minority products of colonial educational establishments who reacted strongly against its brainwashing processes and who became genuine socialist and African nationalist revolutionaries. It is the task of this third section of the intelligentsia to enunciate and promulgate African revolutionary socialist objectives, and to expose and refute the deluge of capitalist propaganda and bogus concepts and theories poured out by the imperialist, neocolonialist and indigenous, reactionary mass communications media.

Under conditions of capitalism and neocolonialism, the majority of students, teachers, university staff and others coming under the broad category of “intellectuals”, are an elite within the bourgeoisie, and can become a revolutionary or a counter-revolutionary force for political action. Before independence, many of them become leaders of the nationalist revolution. After indepéndence,they tend to split up. Those who helped in the nationalist revolutionary struggle take part in the government, and are oriented either to the Party nouveaux riches, or to the socialist revolutionaries. The others join the political opposition, or become apolitical, or advocate middle of the road policies. Some become dishonest intellectuals. For they see the irrationality of capitalism but enjoy its benefits and way of life; and for their own selfish reasons are prepared to prostitute themselves and become agents and supporters of privilege and reaction.

In general, intellectuals with working-class origins tend to be more radical than those from the privileged sectors of society. But intellectuals are probably the least cohesive or homogeneous of elites. Most of the intellectuals in the U.S.A., Britain and in Western Europe belong to the Right. Similarly, the aspirations of the majority of Africa’s intellectuals are characteristic of the middle class. They seek power, prestige, wealth and social position for themselves and their families. Many of those from working-class families aspire to middleclass status, shrinking from manual work and becoming completely alienated from their class and social origins.

Where socialist revolutionary intellectuals have become part of genuinely progressive administrations in Africa, it has usually been through the adoption of Marxism as a political creed, and the formation of Communist parties or similar organisations which bring them into constant close contact with workers and peasants.

Intelligentsia and intellectuals, if they are to play a part in the African Revolution, must become conscious of the class struggle in Africa, and align themselves with the oppressed masses. This involves the difficult, but not impossible, task of cutting themselves free from bourgeois attitudes and ideologies imbibed as a result of colonialist education and propaganda.

The ideology of the African Revolution links the class struggle of African workers and peasants with world socialist revolutionary movements and with international socialism. It emerged during the national liberation struggle, and it continues to mature in the fight to complete the liberation of the continent, to achieve political unification, and to effect a socialist transformation of African society.-It is unique. It has developed within the concrete situation of the African Revolution, is a product of the African Personality, and at the same time is based on the principles of scientific socialism.