Trotsky and the Military Conspiracy (Grover Furr, Vladimir L. Bobrov, Sven-Eric Holmström)

More languages

More actions

Trotsky and the Military Conspiracy | |

|---|---|

| |

| Author | Grover Furr, Vladimir L. Bobrov, Sven-Eric Holmström |

| Publisher | Erythros Press and Media |

| First published | 5 January 2021 |

| Type | Book |

| ISBN | 0578816032 |

Trotsky and the Military Conspiracy: Soviet and Non-Soviet Evidence Evidence; with the Complete Transcript of the "Tukhachevsky Affair" Trial is a 2021 book by historian Grover Furr, published by Erythros Press and Media.

Acknowledgements and Dedication

I wish to express my gratitude to Kevin Prendergast, Arthur Hudson – Arthur, may you enjoy your well-deserved retirement! — and Siobhan McCarthy, the skilled and tireless Inter-Library Loan librarians at Harry S. Sprague Library, Montclair State University.

Without their help, my research would simply not be possible. With their continued help, I can persevere.

I would like to recognise Montclair State University for giving me a sabbatical leave in the fall semester of 2015, and special research travel funds in 2017, 2019, and 2020, which have been invaluable in my research on this book.

This book is dedicated to

Ушкалов Вячеслав Николаевич

Vyacheslav Nikolaevich Ushkalov

The Authorship of This Book

This book is the result of a collective effort. The research has been done primarily by Vladimir L. Bobrov, of Moscow, and secondarily by me, Grover Furr.

Since before he first contacted me in March, 1999, Vladimir Bobrov has been diligently scouring published materials in order to identify and collect primary source evidence and scholarship on the Tukhachevsky Affair. During the past decade, he and a colleague have spent countless hours in the archive of the Federal Security Service, where the records of the former NKVD are stored, locating, reading, and transcribing by hand a great many primary source documents concerning the military conspiracy.

Vladimir has also carefully read and critiqued drafts of this book. I have included most, if not all, of his suggestions in the final text. Without his work, the present book would not have been possible.

Sven-Eric Holström has ably translated the entire transcript of the trial of the defendants in the "Tukhachevsky Affair." I have carefully studied this translation and made a small number of changes.

I have written the text of the book and am responsible for the final draft.

Grover Furr

Montclair, NJ USA

25 November 2020

Foreword: How to Read This Book

The principal document presented here is the complete translation of the transcript of the trial of the defendants in the "Tukhachevsky Affair" – Marshal of the Soviet Union Mikhail N. Tukhachevsky and his seven co-defendants, all top-ranking Red Army officers.

Read this text carefully and – preferably – several times.

Properly understood, this document, and this book, overturn the mainstream history of the Soviet Union, of World War II, and also, in a number of important respects, of the world in the twentieth century.

The other chapters contain confirmatory evidence, with careful and appropriate analysis. They are important, because dishonest historians will claim that Tukhachevsky et al. were not guilty; rather that they were "framed." They will further claim that Leon Trotsky, who is deeply implicated in the Military Conspiracy, was also "framed." These claims are demonstrably false. This book presents the evidence. So these chapters are important.

But read the text carefully. Objective, discerning readers will see for themselves.

Introduction – The Tukhachevsky Affair

On 10 June 1937, the front page of The New York Times broke the story with the following headline:

PURGE OF RED ARMY HINTED IN REMOVAL OF FOUR GENERALS

Five Commands Are Changed, Causing Belief Momentous Events Are Occurring

TUKHACHEVSKY IS OUSTED

Former Marshal Is Thought to Be Under Arrest With Other High Officers

TALK OF COUP DISCOUNTED Marshal Budyonny, Close Friend of Stalin, Is Appointed Head of Moscow Military District

Subheads in the body of the article gave more of the shocking details:

Rumors of Arrests Reinforced

All Distinguished Officers

PURGE OF RED ARMY HINTED IN OUSTINGS

Purges Baffle Diplomats

From the beginning, the guilt of the arrested commanders was widely doubted. On 12 June, Leon Trotsky, living in exile in Mexico, once again predicted Stalin's doom:

TROTSKY SEES STALIN NEAR END OF REIGN Says Interests of Defense Have Yielded to Attempts to Save 'the Ruling Clique'

Trotsky was lying. He himself and his supporters outside and especially inside the Soviet Union, were deeply implicated in this conspiracy which, as we shall see, was a joint military-civilian affair. Indeed, Trotsky himself was one of its leaders.

What Happened

During May, 1937, an undetermined number of officers of the Red Army (formal name: Workers and Peasants Red Army, Russian initials RKKA) were arrested in connection with the investigation of a conspiracy involving high-ranking military officers, together with civilian co-conspirators, to sabotage the Red Army and Soviet defences; open the front in the event of war with hostile powers; and to arrest and/or assassinate Soviet leaders, including Stalin and Marshal Kliment E. Voroshilov, People's Commissar for Defence.

The officers of the highest rank who were ultimately tried, convicted, and executed on 11-12 June 1937, were:

Mikhail Nikolaevich Tukhachevsky, one of the five Marshals[1] of the Soviet Union. Tukhachevsky was arrested on 22 May 1937.

Yona Emmanuilovich Yakir, Komandarm 1st rank[2], arrested on 28 May 1937.

Yeronim Petrovich Uborevich, Komandarm 1st rank, arrested on 29 May 1937.

Avgust Ivanovich Kork, Komandarm 2nd rank,[3] arrested on 12 May 1937.

Robert Petrovich Eideman, Komkor,[4] arrested on 22 May 1937.

Vitovt Kasimirovich Putna, Komkor, arrested on 20 August 1936.

Boris Mironovich Fel'dman, Komkor, arrested on 15 May 1937.

Vitalii Markovich Primakov, Komkor, arrested on 14 August 1936.

Putna had been named by defendants in the second Moscow Trial of January, 1937, as a secret Trotskyist conspirator within the army.[5] Putna had also been mentioned in the first Moscow Trial of August, 1936.[6]

On 20 May 1937, Yan Borisovich Gamarnik, Army Commissar 1st rank, was removed from his post as Chief of the Political Directorate of the Army. On 30 May 1937, the Politburo dismissed him from his military positions because of his "close group ties with Yakir, now expelled from the Party for participation in a military-fascist conspiracy." On 31 May 1937, two officers, acting under Voroshilov's orders, visited Gamarnik at his apartment to inform him that he was being dismissed from the army. When they left, Gamarnik committed suicide by gunshot.

Interrogations of the eight accused continued throughout the last part of May until the trial, which took place on 11 June 1937.

Meanwhile, between 1 June and 4 June 1937, an enlarged session of the Military Soviet (Council) with the People's Commissar for Defence was held in Moscow. The transcript of the discussions was published in 2008. Its purpose was to explain to high-ranking military officers the evidence against the eight commanders in what would come to be known as the "Tukhachevsky Affair;" to present them with that evidence in written form; and to hear what they had to say about it.

The documents presented, evidently in multiple copies, to the officers who attended the Military Soviet, are listed in the transcript of the enlarged session of the Military Soviet. On 1 June 1937, the first day of the meeting, the officers in attendance, 173 of them, were given copies of the confession statements of Tukhachevsky, Kork, Fel'dman, and Yefimov.[7] Other materials may have been distributed after 1 June – an excerpt from a 2 June 1937 confession by Putna is included in the published transcript of the session of the Military Soviet. As of 2020, most of the investigative materials are now available to researchers at the FSB archive in Moscow.

Interrogators of and confessions by these eight men evidently continued right up until 10 June 1937, the day before the trial. On 11 June the eight former commanders were put on trial by a military court consisting of high-ranking officers. The accused and the judges were all well acquainted with one another. The presiding judge was Vasilii Vasil'evich Ul'rikh, an Old Bolshevik[8] and a trained and experienced jurist.

The trial took place on 11 June 1937. All eight defendants confessed, were convicted, and sentenced to execution. They were shot on 12 June 1937. The transcript of this trial is the primary document presented in the present book.

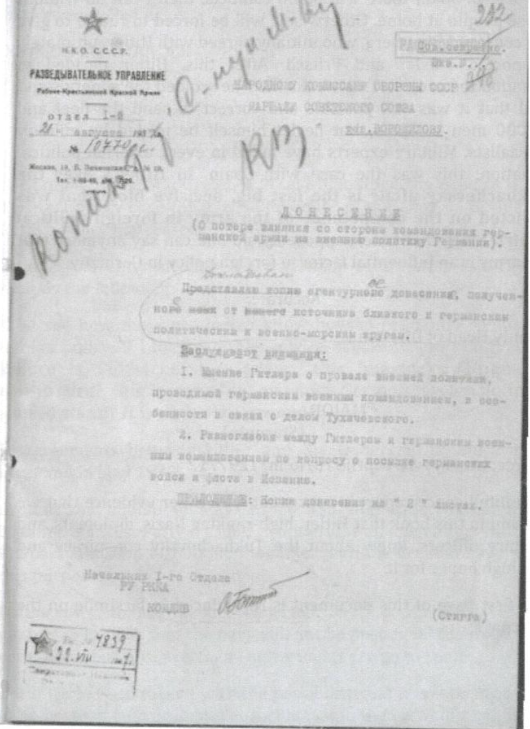

Soviet Archival Documents

Since the end of the Soviet Union in late December, 1991, a great many documents from former Soviet archives have been published. Beginning as a relative trickle, a decade later the total number of former Soviet documents published had become a flood, one that continues until the present day. These documents demand a complete revision of the history of the Soviet Union during the time when Joseph Stalin was in the leadership, roughly 1929 to 1953.

In Russia today there is a law according to which secret documents are to be made public after the passage of 75 years.[9] 2012 marked seventy-five years since the Tukhachevsky Affair. By 2012, many interrogations, statements, and confessions of military men accused of involvement in the military-civilian conspiracy had indeed been declassified.

In 2015 historian Vladimir L. Bobrov, together with a colleague, applied to the archive of the FSB, the agency that is the direct descendent of the OGPU-NKVD-KGB, to request that the transcript of the Tukhachevsky trial be declassified and made available for study. The FSB archive refused, stating that the case was still under investigation by the prosecutor's office.

The Trial Transcript Declassified

In May 2018, a copy of the trial transcript held in a different archive, RGASPI, the Russian State Archive of Socio-Political History, was silently published by being placed on two web pages, one in Ukraine, the other in Russia.[10] This is the text we present here, in English translation. We still do not have access to the copy held in the FSB archive.

The trial transcript is contained in several different archival volumes. Volume 16 ("tom 16") is the first typewritten transcript of the handwritten transcripts recorded by stenographers. It contains only light editing. Volume 17 ("tom 17"), also a typescript of the transcript, contains copious revisions in blue, red, green ink and pencil. The version from the RGASPI archive, which we translate here, is a retyped version of volume 17.

Other Arrests and Trials of Military Men

The trial transcript makes it clear that many other officers were involved in this conspiracy. Today there is a massive amount of evidence to this effect – so much, indeed, that a multi-volume set would be needed to contain it all. We will cover a very small part of this evidence in some of the chapters in this book.

A great many officers were either charged with serious crimes or dismissed from the military under a cloud of suspicion. A significant number were put on trial and either executed or sentenced to terms in a labour camp. Some were acquitted. Others were arrested, held during an investigation, and ultimately released.

A great deal of material has now been declassified and is available to researchers. It is likely that all, or almost all, of the investigative materials on thousands of officers who were under investigation, is still extant and could be accessed and studied by researchers.

But it appears that there is very little research being conducted on these men, or on the subject of the military conspiracy generally.

The main reason for this neglect is the fact that the question of the military conspiracy is widely considered a "closed book." Tukhachevsky and his seven co-defendants have long since been declared to have been innocent victims of a frame-up by Stalin. There is no indication that the mainstream historical profession in Russia or elsewhere is willing to revisit these events, regardless of how much evidence of their guilt we now have.

The Anti-Stalin Paradigm

Refusal to be objective – to consider the possibility that not just the Tukhachevsky Affair defendants, but many other military officers, may have indeed been guilty, to decide the matter of guilt or innocent on the basis of evidence rather than of preconceived ideas, outright bias, or political expediency – is a product of the anticommunism, in the form of anti-Stalinism.

Leon Trotsky did his best to demonise Stalin – to accuse him of every conceivable crime, always without any evidence – in order to further his, Trotsky's, own anti-Soviet conspiracies and his collaboration with Nazi Germany and militarist Japan, and with fascists, German spies, and his own followers within the Soviet Union. After Stalin's death Nikita Khrushchev falsely accused Stalin of many crimes in his famous "Secret Speech" to the XX Party Congress of 25 February 1956. Thanks to evidence from former Soviet archives we now know that all of Khrushchev's accusations against Stalin in that speech are false, most of them deliberate lies.[11]

At the XXII Party Congress in October, 1961, Khrushchev sponsored further accusations against Stalin, some of them citing evidence that we can now show was false. After the XXII Congress, Khrushchev sponsored a virtual avalanche of dishonest writings, disguised as history but devoid of evidence, in which Stalin was accused of yet more crimes. This wave of anti-Stalin fabrications ceased shortly after Khrushchev was ousted in October, 1964.

Beginning in 1987 Mikhail Gorbachev, the final leader of the Soviet Union, launched an even more fierce attack on Stalin, again with the aid of phony historians and with either falsified evidence or no evidence at all. This last anti-Stalin onslaught has continued to the present day.

The unwritten rules of this Anti-Stalin Paradigm (ASP) include the following: It is considered illegitimate to question Stalin's guilt in any crime he has been charged with in the past, regardless of the evidence now available. Confirmation bias, "the tendency to search for, interpret, favor, and recall information that confirms or support one's prior beliefs or values,"[12] trumps evidence, trumps the truth, trumps everything.

In 1956, shortly after his "Secret Speech," Khrushchev assigned a commission under the chairmanship of Vyacheslav Molotov, a long-time close associate of Stalin's, to investigate some of the crimes that Khrushchev had accused Stalin of. The Molotov Commission included a few other longtime Stalin supporters, but also some Khrushchev loyalists. The result was that the commission could not agree that the defendants in the three Moscow Trials had been innocent. But it did "rehabilitate" the principal defendants in the Tukhachevsky Affair, although it cited no evidence in doing so.[13]

Just prior to the XXII Party Congress Khrushchev appointed another commission under the chairmanship of another Old Bolshevik, Nikolai Shvernik, and composed solely of Khrushchev loyalists and Stalin-haters. This commission investigated the Tukhachevsky Affair again, and again found the defendants innocent. Once again, they were unable to find any evidence of innocence, and were forced to falsify the evidence that they did cite. We examine some of the falsifications of the Shvernik Commission in the present book.

My Road to the Tukhachevsky Affair

I first became interested in the Tukhachevsky Affair in the 1970s. At a huge demonstration in Manhattan in 1967 against the U.S. Invasion of Vietnam, I was told by a friendly but clearly anticommunist onlooker that I should not oppose the American war in Vietnam. Why not? I asked. Because – came the answer – the Vietnamese nationalists were led by the Communist Party, the Communist Party was led by Ho Chi Minh, Ho had been trained by Joseph Stalin, and "Stalin had murdered 20 million people."

I did not believe this – but neither did I disbelieve or dismiss it. In 1968 Robert Conquest published The Great Terror: Stalin's Purge of the 'Thirties. I was still curious about the claim that Stalin was a mass murderer, so in the early 1970s I read Conquest's book very carefully. From my study of mediaeval literature, I knew not to take the fact-claims of "experts" on trust, but to always scrutinise the primary-source evidence. So I paid particularly close attention to Conquest's footnotes – where the evidence is. Or, rather, where it is supposed to be.

I had a contradictory reaction to Conquest's book. On the one hand, I was shocked and troubled by the enormous number of accusations of terrible crimes that Conquest levelled at Stalin. On the other hand, I noted that Conquest cited little – if indeed any – primary-source evidence to support his sweeping allegations against Stalin and the Soviets.

Once I was securely situated in my new college teaching job and had completed most of the research for my doctoral dissertation, I set about checking Conquest's book further with the resources of the New York Public Library. I created a 3x5 file card for every citation that Conquest used in The Great Terror and I systematically checked all of them. What I discovered was enlightening. Conquest had no primary source evidence. All of the materials he cited as "evidence" were assertions by Soviet or Western anticommunist writers. I noted especially the fact that the Soviet references also had no evidence.

When I completed by doctoral dissertation in 1978, I determined that I would do some serious research on the "Great Terror." I decided to concentrate on the Tukhachevsky Affair because it seemed to me that there was more information available about it than about the other alleged "crimes of Stalin" in Conquest's book. I began to collect articles and books, and to make notes.

In 1980 I obtained a copy of J. Arch Getty's doctoral dissertation, which he had completed at Boston College the previous year. I read it with enthusiasm. Here was a younger scholar who really knew how to use evidence, and who saw through many of the falsifications that were spread around as "truth" by mainstream scholars like Conquest.

I met Getty, and he suggested that I draft an article for a journal, Russian History / Histoire Russe, for which he was one of the editors. I did this, and after many rewrites, Getty recommended it for publication. But the publisher of the journal, Charles Schlacks, rejected my article on the grounds that "it made Stalin look good." Of course, my article did not do that at all. But it did conclude that the accepted version of Tukhachevsky's innocence was not supported by any evidence, and that in fact we did not know whether Tukhachevsky was innocent or not. The publisher found such responsible, scholarly caution to be unacceptable.

But Getty stood up for my article. He told the publisher that it must be published, because it had gone through a very careful vetting by himself and some colleagues. The publisher backed down. But when the article was published, in 1988 (the issue is dated 1986), the prefatory essay to the issue contained an introductory paragraph discussing every article – except mine! This was my first exposure to what I now call the Anti-Stalin Paradigm.

In 1996 I learnt how to create a simple web page. On it I put retyped versions of all the articles I had published by that time, including the 1986/88 article on Tukhachevsky. In March 1999 I received an email from Vladimir L'vovich Bobrov in Moscow about my article. He told me the article was good but that it should be updated by the study of some of the many documents from former Soviet archives that had begun to appear in Russia.

Vladimir had been collecting and retyping documents related to the Tukhachevsky Affair and generously shared them with me. He wanted us to write an article or a book about it. I agreed, and for a while I did some work on it. But then I stumbled across evidence that Nikita Khrushchev had lied – indeed, had virtually done nothing but lie – in his famous "Secret Speech." So I stopped working on Tukhachevsky and began years of researching and writing on other important questions of Soviet history of the Stalin period, beginning with Khrushchev Lied.

In 2007-8 I undertook a systematic review of all the documents in the Volkogonov Archive[14] pertaining to the Stalin years. I discovered a report by Marshal Semyon Budyonny to Marshal Voroshilov in which Budyonny, a member of the judicial panel, describes the Tukhachevsky trial. This document was classified – secret, unavailable to researchers – in Russia at that time. In 2012 Vladimir and I published this document in the St. Petersburg historical journal Klio. Our article, including our analysis of Budyonny's letter and how it has been dishonestly described over the years, is also available online, though only in Russian.[15]

Now that the transcript of the trial has been made public, along with a great many other documents relating to the military conspiracy, it is time to return to the Tukhachevsky Affair.

— Grover Furr, 2020

The Trial Transcript

The main feature of this book is the presentation of a complete English translation of the transcript of the trial of Tukhachevsky and his seven co-conspirators. This translation was expertly done by my Swedish colleague and fine historian Sven-Eric Holström. I take responsibility for its accuracy, since I have gone over it and corrected it on some minor points.

Annotations to the Transcript

Within the transcript itself I have included footnotes to clarify some issues. In addition, there is one chapter on the "Spravka" (report) of Shvernik Commission, set up by Khrushchev to whitewash Tukhachevsky et al. This chapter is not an exhaustive study of the Spravka – it is far too long, and there are far too many lies and fabrications in it. Rather, this chapter only covers the parts of the Spravka that deal directly with the trial transcript.

There are two chapters on books that lie about the Tukhachevsky Affair. These chapters are very far from exhaustive – all books by mainstream historians that mention the trial lie about it. I have chosen these specific books as exemplary.

Confirmatory Evidence

There follows six chapters on Soviet evidence and three chapters on non-Soviet evidence that confirms the existence of the military conspiracy. I have selected only evidence that I regard as unimpeachable – that cannot have been fabricated or faked. Much of this evidence has been available for years.

In fact, there has never been any evidentiary reason to doubt the existence of this conspiracy. Neither Khrushchev's nor Gorbachev's writers, nor any scholars or writers outside the Soviet Union, have ever presented any evidence that Tukhachevsky & Co. were innocent or that the conspiracy did not really exist.

But the combined impact of decades of assertions from supposedly authoritative persons, plus the effects of anticommunism, which incline even scholars who ought to know better towards confirmation bias – believing what they want to believe, i.e. that Stalin framed everybody – has done its work. It has convinced most people who were concerned about the Tukhachevsky Affair at all, to believe the claims that the defendants were innocent.

The Anti-Stalin Paradigm: Lies and Denial

In the professional field of Soviet history it is considered not just inappropriate, but unthinkable, "taboo," to conclude that Stalin did not commit some crime of which he has been previously charged. It doesn't matter how flimsy the evidence – or if, indeed, there ever were any evidence – of Stalin's guilt is. Nor does it matter how good the evidence is that Stalin did not commit the alleged crime. Evidence, literally, does not matter. What matters is "political correctness" – the imperative to condemn Stalin, to find him guilty of the crime alleged. Therefore, this book will be ignored by professionals in the field of Soviet history.

It will also be ignored by adherents of the cult around Leon Trotsky. Trotskyists (as they prefer to be called) uncritically repeat not only all the lies and fabrications that Trotsky himself produced – and we have shown in previous books that Trotsky produced a great many demonstrable lies.

Trotskyists also publicise, as loudly and as widely as they are able, any and all lies and fabrications produced by professional researchers in the field of Soviet history. It does not matter how overtly anticommunist, or even how anti-Trotsky, these researchers may be. As long as they blame Stalin for crimes – any crimes – their fictions are repeated as truths by the Trotsky cult.

Likewise, there are many people who self-identify as socialists and/or as Marxists who will reject the evidence and analysis in this book. Such socialists, sometimes known as social democrats, are ideologically committed to anticommunism and especially to hostility towards Joseph Stalin, about whom they know nothing except falsehoods. Like the Trotskyists, these socialists have been drinking from the poisoned well of mainstream anticommunist scholarship for so long that they have become incapable of thinking rationally and objectively.

But there are far more people who want to know the truth about the first socialist state in world history. Many tens of millions of people around the world respect the role the USSR played, especially during the Stalin period, in organising the fight against the murderous, exploitative imperialism of the so-called "democratic" countries.

They know that the USSR went in little more than a decade from being a backward agricultural society to an industrial power that was able to defeat the fascist invasion that was led by the German Wehrmacht, the most powerful military machine the world had ever known.

They know that the Soviet Union gave unprecedented benefits to working people – cheap rent, transportation, free medical care, guaranteed vacations, maternity leave, sick leave, old age pensions – benefits that, for example, few citizens of the United States of America enjoy. They remember when the Soviet Union, during Stalin's time, promised to push ever forward from socialism toward a classless society of justice – communism.

These people are the crucial force that will bring a better world into being. This book is for them.

Chapter 1. The Shvernik Report – Khrushchev-era Falsifications

At the XXII Party Congress of 17 – 31 October 1961, Nikita Khrushchev oversaw a large-scale attack on Joseph Stalin and his main supporters in the Party leadership. The accusations directed against Stalin were fraudulent – accusations of crimes that Stalin did not commit and, in many cases, that were not crimes at all.

The attacks against Stalin descended to the absurd when Dora Abramovna Lazurkina, an Old Bolshevik who had spent 18 years in the GULAG told the Congress that she had "spoken" with the long-dead Lenin.

"Товарищи! Мы приедем на места, нам надо будет рассказать по-честному, как учил нас Ленин, правду рабочим, правду народу о том, что было на съезде, о чем было сказано, что было вскрыто, рядом с Ильичей остается Сталин.

Я всегда в сердце ношу Ильича и всегда, товарищи, в самые трудные минуты, только потому и выжила, что у меня в сердце был Ильич и я с ним советовалась, как быть. (Аплодисменты). Вчера я советовалась с Ильичем, будто бы он передо мной как живой стоял и сказал: мне неприятно быть рядом со Сталиным, который столько бед принес партии. (Бурные, продолжительные аплодисменты)."

"Comrades. We have arrived at the place where we must tell honestly, as Lenin taught us to do, the truth to the workers, the truth to the people about what has happened and what we have discussed at the Congress. And it would be incredible if, after everything that has been said and disclosed here, Stalin remained beside Lenin.

I always carry Ilich in my heart and always, comrades, in my most difficult moments, the only reason I survived is that Ilich was in my heart and I could consult with him what to do. (Applause) Yesterday I consulted with Ilich, as though he were alive and stood before me and he said: It is unpleasant to be next to Stalin, who brought so many disasters to the Party. (Stormy, prolonged applause.)"[16]

The Congress voted, and Stalin's body was removed from the Lenin Mausoleum on Red Square.

The Shvernik Report is composed of two parts: the "Spravka", or Report, and the "Zapiska," or Memorandum. They were submitted to Khrushchev at different times. We are concerned with the Spravka which, according to the editors' note accompanying it, was completed not later than 26 June 1964. The Spravka is devoted to the rehabilitation of the defendants in the Tukhachevsky Affair; the Zapiska, to many other Party members who had been repressed during the Stalin period.

Neither the Spravka nor the Zapiska was published while the Soviet Union existed. Beginning about 1993, they were published in a number of different journals. Some of these early editions are still cited by historians today. At length they were published in the second volume of the semi-official series of volumes titled Reabilitatsiia. Kak Eto Bylo[17] – "Rehabilitation. How It Happened." The Spravka is on pages 671-788 of this volume. This is by far the most accessible print version of the Shvernik Report and we will use it here. A transcription of the Spravka is also available online.[18]

Both parts of the Shvernik Report are blatant falsifications. At the time the Shvernik Report was first published, in the 1990s, relatively few documents from former Soviet archives had yet been published. So when the Report first appeared, it was widely accepted as truthful. Today we can identify many of these deliberate lies, thanks to the publication of a great many documents from former Soviet archives since the end of the USSR in 1991.

Here we will focus on lies of omission in the Spravka about the Tukhachevsky Trial transcript. The Spravka reproduces sentences taken out of context in order to argue that the defendants were innocent.

First passage: Blyukher and Yakir

... when Blucher, trying to specify the preparations for the defeat of the Red Army aviation in a future war, asked a question about this, Yakir answered: "I really can't tell you anything, apart from what I wrote to the investigation."

When asked by the chairman of the court how the sabotage of combat training expressed itself, Yakir evasively stated: "I wrote about this issue in a special letter."

(RKEB 2, 690)

From these two short passages it appears that Yakir simply refused to answer. In reality, this was not at all the case. Here are the passages in the text of the trial transcript:

Blyukher: Accused Yakir, what exactly were your preparations for the defeat of the Red Army aviation in a future war?

Yakir: I really can't tell you anything, apart from what I wrote to the investigation. I said that, firstly, I imagine in such a way that in parallel with our wrecking work, which only slightly related to aviation, some central organisation carried out very large wrecking cases in aviation, both in matters of materiel (about which I testified in detail), and in a whole series of other questions: staffing, logistics, etc. .. Firstly, the Shepetovsky airdrome was built in a wrecking manner, which was done by an air force engineer named Kikachi, despite the fact that Veingauz was present there and did not notice anything. Secondly, they surely sabotaged in the construction of other airfields. They sabotaged the organisation of the airfield network, which in the vast majority, would either not allow, or would complicate the work of high-speed aviation. Aviation moves at high speeds, needing large take-off spaces, and airfield sites are not growing enough and can put aviation in a difficult position. In addition, much wrecking work was carried out on the material and technical areas, on material and technical supply and personnel. Thirdly, there was a lack of haste and lack of encouragement of the aviation units which were absolutely necessary and without which it was impossible to work during night flights, especially in high-speed aviation. (16-17)

The President: How did the sabotage of combat training manifest itself, aside from limiting aviation night flights?

Yakir: I spoke about this issue in a special letter. I think that there was no need to apply special sabotage, since there were many disorders in this matter. We slowed down work in field high-speed night flight and relied on a similar line coming from Moscow, which did not give us anything. This business was simple, since everything was being rebuilt in our country, and therefore it did not present any difficulties. (19-20)

Second passage: Dybenko and Yakir The Spravka reads:

T. DYBENKO: - When exactly did you personally begin to conduct espionage work in favour of the German General Staff? Yakir: I did not personally and directly begin this work. (RKEB 2, 700)

But in Yakir's confessions we find the following passages:

I heard about espionage twice about the Tukhachevsky about the Red Army, once through Colonel Koestring and the second time through General Runstedt. (л.д.21об)

I understand that I, as a member of the Central Committee, bear more responsibility than all other participants of the conspiracy. With access to all the most secret party and government documents I was aware of all matters and could inform the centre about them. (л.д.31)

In addition, I informed at different times members of the Centre of the Military Conspiracy on the relations in the Ukrainian leadership. For my testimony, this question does not matter for this is a well-known business. (л.д.87об)

That is, Yakir did not transmit information directly to the General Staff of Germany, but passed it to the members of the conspiratorial centre.

We should bear in mind that, in accordance with Soviet law, the crime of espionage is not considered committed when the fact of recruitment is established or when espionage information is transferred to a representative of a foreign state. A crime is considered to have been committed when actions are taken to collect information for the purpose of transferring it. It does not matter to whom it was directly planned to transfer such information – foreign states, counterrevolutionary organisations, or private individuals. Therefore, the accusations of espionage against Yakir were true.

Third passage: Dybenko and Uborevich

Dybenko: Did you directly conduct espionage work with the German General Staff? Uborevich: I never did that. (RKEB 2, 700)

This gives the impression that Uborevich was innocent of any crime. The passage in the trial transcript tells a different story.

Dybenko: Did you directly conduct espionage work with the German General Staff?

Uborevich: I never did that.

Dybenko: Do you consider your work to be espionage and sabotage?

Uborevich: Since 1935, I have been a saboteur [lit. wrecker], a traitor, and an enemy. (78)

Uborevich did refuse to plead guilty of espionage, but he fully confirmed the commission of crimes of treason – something directly opposite to what is suggested in the Spravka. Fourth passage:

Feldman, like Kork, was the "hope" of the investigating authorities ... Feldman's speech occupied 12 pages of the transcript. (RKEB 2, 690)

In reality, the interrogation of Tukhachevsky occupies 35 pages of the transcript; of Yakir, 33 pages; of Kork, 28 pages, and of Fel'dman, 14 pages (not 12). Tukhachevsky and Yakir confessed at much greater length during the trial than the rest of the defendants.

Chapter 2. Evidence that the Defendants' Testimony was Genuine

An important episode in the trial occurs when Tukhachevsky addresses Ul'rikh with a request to give additional details to his confession about sabotage. Ul'rikh agrees.

The President: Have you met with a representative of Polish intelligence in recent years?

Tukhachevsky: No. May I supplement my confession?

The President: Please do.

Tukhachevsky: I would like to add concerning some basic questions of wrecking. (54)

Shortly thereafter Ul'rikh interrupts Tukhachevsky with a leading question.

The President: I have another question. Who, handed over to Polish intelligence some data of the Letichev district, and who issued this assignment?

Tukhachevsky: I personally.

The President; Please add what you wanted. (55)

Tukhachevsky then tries to briefly summarise some of the facts that he had described in detail in his note dated 1 June 1937. Ulrich loses patience with these theoretical remarks:

The President: Please stick more closely to the question than you wanted to talk about. (56)

But Tukhachevsky continues to speak in the same manner. Ul'rikh interrupts him again:

The President: Stick closer to the subject. (56)

Tukhachevsky continues to go on and on. At last, Ul'rikh loses patience:

The President: You are not giving a lecture or a report. You are making a confession. (62)

Tukhachevsky: I am talking about those wrecking cases that we did. These are the main points of wrecking, espionage, and sabotage, which I can tell you about.

I want to assure you that I said all that I know on the basic questions. (62-3)

This fragment of the transcript clearly proves that the trial was not staged. Moreover, for whom could it have been staged? Who could have been a spectator of such a production? The trial took place behind closed doors. The transcript was in secret storage for 75 years. Even after this period it remained inaccessible to researchers for several more years.

The Absence of Any Prepared Scenario for the Trial

Dialogues about who became a participant in the conspiracy and when they did are clear evidence of an absence of any scenario prepared by the investigators and/or by preliminary collusion between the defendants. The judges listen to the parties in order to clarify and correct discrepancies in the testimony.

Dybenko: In 1929, when you were sent to Germany, were you not connected with the German Reichswehr?

Kork: Not yet at that time. Communication was established only in 1931, when I stepped down from the position of an honest Soviet citizen to the position of betrayer and traitor to the motherland, and together with me on the road to struggle against the party followed Tukhachevsky, Yakir, Uborevich, and others.

Dybenko: So it can be stated that Uborevich and Yakir, giving confession to the court, falsely stated that they were involved in a counterrevolutionary organisation in 1934?

Kork: Yes, I insist on my confession. I know that they were not involved in the organisation in 1934, but in 1931 simultaneously with me. (101-2)

Judge Ul'rikh then breaks in to check to see what Uborevich has to say about this.

The President: Accused Uborevich, from what year did you consider yourself a member of a military organisation when you joined the fascist military organisation?

Uborevich: Defeatist assignments were set before me in March, 1935, and conversations were conducted from the end of 1934. Prior to this, I did not engage in counterrevolution.

The President: So, the confession of Kork that you entered the organisation in 1931 is wrong? How to explain these confessions of Kork?

Uborevich: I do not know.

Failing to get satisfactory clarification from Uborevich, Ul'rikh turns to Tukhachevsky:

The President: Tell me, Tukhachevsky, how to explain the difference between your confession and Kork's?

Tukhachevsky: I involved Kork in the organisation during the advanced manoeuvres. That was in 1933, and not in 1931, as he claims.

The President: Could it have been conversations of an anti-Soviet character, that was not related to specific actions?

Tukhachevsky: I said that Kork was recruited in 1933. There were conversations of discontent against Voroshilov, against our leadership. There was no concrete talk of a conspiracy until 1933.

The President: Did Kork tell you about the negotiations with Yenukidze concerning the capture of the Kremlin?

Tukhachevsky: Quite right, I informed Yenukidze about this situation after having had a conversation with Gorbachev, and then I informed Kork.

The President: When did you have a conversation about the capture of the Kremlin?

Tukhachevsky: In 1933-1934, when Gorbachev returned. Here, Kork confuses dates. (102-3)

As can be seen, the disagreements are never really cleared up.

Moreover, it is not important for the ultimate outcome of the trial – for the guilt or innocence of any of the defendants – that the defendants agree with one another. Rather, Judge Ul'rikh's purpose is to find out more about the conspiracy. The investigation into the conspiracy, the arrests, interrogations, and trials of more suspects would follow.

We will see below that not all of the military men named by these defendants would be sentenced either to death or to imprisonment. Some would only be cashiered from the service. This is further evidence that the investigation, far from being a frame-up of innocent men, was in reality a serious attempt to uncover a dangerous plot and to save the Red Army and, by doing so, save the Soviet Union.

More about Contradictions in the Defendants' Confessions

In addition to Kork the investigation found that there are some inconsistencies between the testimony of Tukhachevsky and that of Primakov. Such passages indicate the veracity of the testimony.

The President: Accused Tukhachevsky, what do you know about preparing a terrorist attack against Voroshilov?

Tukhachevsky: In a conversation with Primakov I learnt that Turovsky and Shmidt were organising a terrorist group against Voroshilov in the Ukraine. In 1936, from conversations with Primakov, I realised that he was organising a similar group in Leningrad.

The President: Did you hear Tukhachevsky's confessions?

Primakov: Nothing was proposed to me except to organise an armed uprising. (124-5)

Primakov goes on to give more details about his important assignment, in order to explain why Tukhachevsky's statements about him must be incorrect.

Primakov: I had the following basic instruction: Until 1934 I worked for the most part as an organiser, in gathering Trotskyite cadres. In 1934, I received an order from Piatakov to break off with the group of Dreitser and old Trotskyites, who were assigned to prepare terrorist acts, and I myself was to prepare, in the military district where I worked, to foment an armed uprising that would be called forth either by a terrorist act or by military action. This was the assignment I was given. The military Trotskyite organisational centre considered this assignment to be very important and its importance was stressed to me. I was told to break any personal acquaintance with old Trotskyites with whom I was in contact. This is the reason why I moved away from Dreitser's group, this is why I worked at the assignment that had been given to me. (125-6)

It is important to note that the contradictions in the testimony of the trial defendants prove that they did not tailor their testimony according to a prepared scenario. Equally important, it is clear that the prosecution did not falsify the record of the trial – the transcript – in order to eliminate inconsistencies.

During the preliminary investigation, in order to find out the reasons for the contradictions in the testimony of Kork and Tukhachevsky, the investigators drew on the testimony of Yenukidze, Gorbachev, and Primakov. The investigators approached the study of such contradictions more thoroughly than the future authors of the Shvernik Report, which passes as certification of "rehabilitation."

If all the testimonies of Tukhachevsky and others had been imposed on them by a team of investigators, where did these contradictions come from? How could they survive before the trial?

The presence of these contradictions, the attempts of investigators and judges to understand them, constitutes the strongest evidence that the persons under investigation and the defendants testified as they chose to testify – that is, gave mainly truthful testimonies. At the same time, everyone described the events as they remembered them, and not in the way that the investigators and judges would have liked.

The Trial Exposed Zybin and Tkachev

On 11 June 1937 – that is, the very day of the Tukhachevsky trial – I.M. Leplevsky, Chief of the Special Department of the Main Directorate for State Security of the People's Commissariat of Internal Affairs of the Soviet Union, appealed to Kliment E. Voroshilov:

According to the testimony of the arrested member of the anti-Soviet military conspiracy Primakov V.M., Zybin, commander of the 26th cavalry division, is a participant in this conspiracy. I ask your permission to arrest Zybin. Two days later, a resolution appears on this memorandum: "Arrest him. KV. 13 / VI.37."

The passage above is quoted from O.F. Suvenirov, Tragediia RKKA 1937-1938 (Moscow: Terra, 1993), page 93. Suvenirov's book takes for granted the Khrushchev – Gorbachev contention that there was no military conspiracy (or, for that matter, any other conspiracies) at all, that all of the arrested and repressed military men were innocent, and that all those repressed were "innocent victims of Stalin." Suvenirov makes no attempt to prove this contention; he simply assumes it. But the factual information in this book appears to be accurate, which makes it a valuable resource if used for this purpose only.

The President: Did you manage to recruit people in Leningrad from the leadership of the units?

Primakov: I recruited some people in Leningrad, got contact with some people, transferred some people from Leningrad to other places. I had to appoint the commander of the Shmidt corps as commander of the 7th corps, I achieved the transfer of Tkachev. I talked to Zybin in Pskov and could count on him during the uprising. I almost finished preparing the commander of the 10th corps, Dobrovolsky, with whom we failed to agree organisationally, and as such he shared our attitude.

Dybenko: And what about the district chief of staff?

Primakov: I didn't directly reach an agreement with Fedotov, but I submitted a statement to the investigator that all the signs that I had about him showed that he was a member of the Tukhachevsky organisation. (128-9)

According to N.S. Cherushev, Viktor Petrovich Dobrovolsky was arrested – but not until either 9 October or 15 October 1937. He was relieved of his command in June 1937 – no doubt as a result of this trial. On 20 September 1938, he was tried and convicted of participation in the military conspiracy, and executed the same day. He was "rehabilitated" under Khrushchev.[19]

Anatolii Vasli'evich Fedotov was relieved of his command in July, 1937. He was arrested on 22 October 1937, tried, convicted, and executed on 20 September 1938, for participation in the military conspiracy. He was "rehabilitated" on 17 October 1957, under Khrushchev.[20]

Mark L'vovich Tkachev was arrested on 4 June 1937. He was tried, convicted, and executed on 1 September 1937, for participation in the military conspiracy. According to Cherushev, he was "rehabilitated," but no date is given.[21]

Sergei Petrovich Zybin was commander of the 25th cavalry division, located in Pskov. He was "under investigation" – which means in detention – from June, 1937, which is the correct time if he is the Zybin named by Primakov. But he was released in April, 1940, the investigation was ended and he was reinstated in the Red Army.

Vladimir Bobrov has obtained Primakov's interrogation of 11 May 1937, in which Zybin is mentioned five times. In it Primakov talks about the plan to bring Trotsky to Leningrad during the course of the armed insurrection, which Primakov was in charge of.

QUESTION: – From whom did you receive the instruction on the development of a plan for the preparation and support of Trotsky's crossing in the USSR? ANSWER: – I did not receive such instructions from the Trotskyist centre. I independently developed a plan for ensuring Trotsky's crossing in the USSR, which I intended to propose to the Trotskyist military centre in the fall of 1936 when developing this plan. I proceeded from the premise that at the moment of the acute struggle for the seizure of power by the Trotskyists, Trotsky should appear not just anywhere, but among the troops that are prepared for this. My calculations included Trotsky's crossing from abroad or from the Estonian side, and in this case ensures the crossing and meeting of Trotsky ZYBIN, or from Finland on the border with which there are units of the XIX rifle corps of DOBROVOLSKY, which in this case ensures the crossing and meeting Trotsky.

In his interrogation of 14 May 1937, Primakov states that he did not tell Zybin or Dobrovolsky about his plan for an armed insurrection, but believed that he could count on them when the time came. Evidently the prosecution believed that Zybin had been guilty of nothing more than what Primakov called "anti-Soviet words and attitude."

During World War II, on 5 August 1941, Kombrig[22] Zybin was killed as he led his surrounded division to break out of encirclement near Uman' in the Ukraine.[23]

Chapter 3. Soviet and Russian Books That Lie About the Tukhachevsky Affair

Boris A. Viktorov (1916-1993) was a lieutenant-general of Justice. From 1967 to his retirement in 1978 he was Assistant Minister of Internal Affairs. From 1955 throughout the Khrushchev period, Viktorov was Assistant to the Chief Military Procurator Artyom G. Gorniy. There Viktorov worked in a special group evaluating appeals for rehabilitations of persons imprisoned or executed during the Stalin period.

During the late Gorbachev period Viktorov wrote several articles about supposedly unjust repression of persons whose cases he had studied. In 1990 he published a book, Without the "Secret" Stamp (Bez grifa 'sekretno'). This book, published during Gorbachev's attack on Stalin and massive dishonest rehabilitations of persons falsely claimed to have been unjustly repressed, was published in 200,000 copies – an enormous press run for what is basically an academic-style study of alleged unjust repressions.

The fact-claims in Viktorov's books could not be vetted – checked for accuracy – when it was published. Gorbachev's USSR was still in existence. The flood of documents from former Soviet archives had not yet begun.

Now, however, we can check many of the assertions that Viktorov made. Those that we have checked turn out to be false. The book is not an objective study of unjust repressions, but a cover-up of the evidence that many "rehabilitated" persons were actually guilty.

This is the case with Tukhachevsky. The example below gives an idea about the extent of the dishonesty in Viktorov's book.

p. 224:

Александр Чехлов в рассказе «Расстрелянные звезды» так охарактеризовал облик следователя М. Н. Тухачевского: Alexander Chekhlov, in the story "The Stars that were Shot", described the appearance of M. N. Tukhachevsky's investigators as follows:

Short stories are, of course, not evidence! p. 231:

Перед нами стенограмма протокола заседания Специального судебного присутствия Верховного Суда СССР, состоявшегося 11 июня 1937 г. Председательствовал армвоенюрист В.В.Ульрих...

Стенограмма содержала всего несколько страниц, свидетельствуюших о примитивности разбирательства со столь тяжкими многочисленными обвинениями.

Before us is the transcript of the minutes of the meeting of the Special Judicial Presence of the Supreme Court of the USSR, held on 11 June 1937. Military jurist V.V. Ulrich presided

the transcript contained only a few pages, which testifies to the primitiveness of the proceedings with such grave and numerous charges.

Page 232:

Аналогичные показания об отношении к Родине лали Уборевич, Корк, Фельдман, Якир, Путна. Якир сообщил, что учился в 1929 году в академии генерального штаба Германии, читал там лекции о Красной Армии, а Корк некоторое время исполнял обязанности военного атташе в Германии. Uborevich, Kork, Feldman, Yakir, Putna gave similar testimonies about their attitude to the Motherland. Yakir said that he studied at the Academy of the General Staff of Germany in 1929, read lectures about the Red Army there, and Kork for some time served as a military attaché in Germany.

So what? In 1929 these men had not yet joined the conspiracy. Page 233:

Каким мог быть пригоров? Его содержание было предрешено приказом наркома обороны СССР К. Е. Ворошилова N2 96 от 12 июня 1937 г. What else could the verdict be? Its content was predetermined by order of the People's Commissar of Defence of the USSR K.E. Voroshilov No. 96 of 12 June 1937.

Again, either dishonest or incompetent. The verdict was not "predetermined." The court rendered its verdict on 11 June. It was signed by Voroshilov on 12 June.

In reality, the transcript is 172 pages long. Viktorov may have been deliberately lying. Or, it may be that he himself had not been permitted to see the transcript. It may even be the case that Viktorov did not write this book, but allowed some ghostwriters to do it for him.

Whatever the case, Viktorov's book is a good example of the utter dishonesty of Gorbachev's "rehabilitations" of people supposedly repressed unjustly.

S. Yu. Ushakov and A.A. Stukalov, The Front of the Military Procurators ("Front voetnnykh prokurorov"). Vyatka, 2000. This widely-cited book is in two parts. The first claims to be the memoir of Nikolai Porfir'evich Afanas'ev, who was active in the office of the military prosecutor in Moscow during the 1930s.

Afanas'ev supposedly wrote his memoir during the 1950s. Ushakov claims that Afanas'ev was afraid to publish them during the Khrushchev "thaw" and afterwards – a claim that sounds doubtful on the face of it, since the contents of this book would fit in perfectly with the falsifications that Khrushchev sponsored by the bushel. According to Ushakov, Afanas'ev's granddaughter asked him to publish them.

We are not concerned here with the question of whether the memoir is genuine – that is, whether it represents what Afanas'ev actually wrote. In the light of documents from former Soviet archives published after the end of the USSR, and particularly after the publication of this book in 2000, we can tell that many statements in it are simply false.

Тухачевский упорно отрицал ка кую-либо свою вину в измене или каком-либо другом преступлении. Не дали результатов и длительные допросы, Тухачевский все время твердил одно - он ни в чем не виновен.

... Пришлось доложить, что Тухачевский категорически отрицает какую-либо свою вину.

... Тухачевский, по словам Ежова, так ни в чем и не признался, хотя к нему и применялись «санкции», как он выразился.

Tukhachevsky stubbornly denied any guilt of treason or any other crime. Long interrogations did not produce results either, Tukhachevsky kept saying one thing - he was not guilty of anything.

... He had to report that Tukhachevsky categorically denied any guilt on his part.

... Tukhachevsky, according to Ezhov, admitted no guilt, even though they applied "sanctions" to him, as he expressed it. (70, 71)

This is entirely false. Two of Tukhachevsky's confessions were published in 1991. In those he did confess guilt. Today we have several hundred pages of Tukhachevsky's investigation file, with a great many confessions of guilt in considerable detail, plus the trial transcript, with many more confession by Tukhachevsky.

Iulia Kantor

Iulia Zorakhovna Kantor is a Russian journalist and historian who in the 1990s obtained permission from the Tukhachevsky family to gain access to the still-classified Tukhachevsky investigation material. She has written several articles and three books dealing with Tukhachevsky.

Kantor has clearly read the transcript of the Tukhachevsky trial. Yet she still insists that Tukhachevsky was innocent! See her very dishonest but nevertheless revealing article in the Russian newspaper Izvestiia of 21 February 2004, page 10-11. It is no longer on line at the Izvestiia site so I have put it online here:

http://msuweb.montclair.edu/~furrg/research/kantor_izvestiia_022104.pdf

On the first page (numbered page 10), upper right corner, can be seen the cover of the trial transcript. It is exactly the same as the one made public in May 2018, and which we have translated here.

On the second page (page 11), upper left corner: the famous "blood spots" appear. But see Tukhachevsky's very regular signature right beside them. In fact, no one knows what they are or, if they are blood, whose blood it may be. We examine these "blood spots" in a separate chapter of this book.

Vladimir Bobrov has studied the Tukhachevsky investigative file and informs me that there are no spots, whether "blood" or otherwise, on this file. There are holes that appear to have been cut out by a sharp instrument, perhaps a razor blade. It appears as though Kantor claimed that she saw the "blood spots" that are mentioned in the "Spravka" in order to facilitate the myth that Tukhachevsky had been beaten.

In 2006, Kantor wrote four articles for the journal Istoriia gosudarstva i prava (History of the state and the law) titled "Hitherto unknown documents from the 'Tukhachevsky Affair'" ("Neizvestnye dokumenty o 'dele voennykh'"). I have put these texts online, though they are not translated into English. In them are many confessions of guilt by Tukhachevsky and the other defendants.[24]

Iulia Kantor, The War and Peace of Mikhail Tukhachevsky (Voina i mir Mikhaila Tukhachevskogo) Moscow: Dialog, 2005).

According to Russian law, documents are declassified after 75 years. When Kantor researched and wrote this book that period had not yet been reached. But since the Gorbachev period direct relatives of any person have been able to obtain access to investigative and judicial records. Kantor obtained permission from the Tukhachevsky family to use family documents and to interview relatives. As can be seen in the reproduction of her 2004 Izvestiia article, she also received access to the trial transcript.

Kantor's book is a continuation of the Khrushchev – Gorbachev cover-up about Tukhachevsky. Presumably, she would not have obtained from the Marshal's descendants access to still-classified documents if she had not agreed from the outset to "prove" Tukhachevsky innocent. Writing at a time before researchers could gain access to classified documents from 1937, Kantor ran no risk that anyone would be able to compare what she wrote with the primary sources that only she had permission to read.

The principal dishonesty in Kantor's book is that she pretends to her readers that the investigative materials of Tukhachevsky prove his innocence and confirm the point of view of the Khrushchev-era rehabilitation. Kantor claims that in these documents she did not find even a single bit of evidence of the slightest wrongdoing by Tukhachevsky.

Kantor has recourse to the pseudo-science of graphology – handwriting analysis – in order to argue that Tukhachevsky was under "stress" when he wrote some of his handwritten confessions. My colleague, Vladimir Bobrov, who has accessed and transcribed many documents from the NKVD files of Tukhachevsky and others in the military conspiracy, says that this is untrue, that Tukhachevsky's handwriting is very even and regular.

В рукописных текстах показаний пляшут буквы, смазываются строчки. (Kantor, 387) In his handwritten testimony the letters dance, lines are blurred.

Vladimir Bobrov comments:

Это утверждение лживо: наоборот, рукописные показания Тухачевского отличаются строгостью соблюдения высоты строчек, границ полей, размером букв, разборчивостью почерка. Множество вставок, замечаний, уточнений свидетельствует о том, что текст писался не под диктовку, а самим подследственным, т.е. факты и формулировки принадлежат Тухачевскому.[25] This statement is false. On the contrary, Tukhachevsky's handwritten confessions are distinguished by strict observance of the height of lines, margin boundaries, letter size, and the legibility of handwriting. The many inserts, remarks, and clarifications indicate that the text was written not under dictation, but by the person under investigation, i.e. the facts and language belong to Tukhachevsky.

I have put three samples of Tukhachevsky's handwriting in his confession file (P-9000) on the Internet. These samples prove that Bobrov's remarks are correct. They may be seen here:

https://msuweb.montclair.edu/~furrg/research/tukh_handwriting_kantor.html

Chapter 4. Western books that lie about the Tukhachevsky affair – Stephen Kotkin

Today we have a great deal of evidence that Marshal Mikhail Tukhachevsky and the seven other high-ranking military commanders who were tried, convicted, and executed with him on 11-12 June 1937, were guilty, as charged, of conspiracy with the Nazis and Japanese, and with Leon Trotsky, to defeat the Soviet Union in a war. Indeed, we have so much evidence that a single volume with appropriate commentary could not hold all of it. But the "official" viewpoint – the only one acceptable in academic, political, and public discussion because it is the only one consistent with the Anti-Stalin Paradigm (ASP) – is that Tukhachevsky and all the rest were innocent, victims of a "frame up" by Stalin for reasons unknown. In order to sustain this viewpoint, all the evidence must be either dismissed as "faked" in some way or simply ignored. Stephen Kotkin chooses the latter strategy: he ignores the evidence.

Stephen Kotkin is a full professor of history at Princeton University. He is also a fellow of the super-anticommunist Hoover Institution, which never sponsors any publication or any scholar that is not intensely anticommunist. Kotkin has spent his entire academic career since graduate school on the Stalin period of Soviet history.

In addition Kotkin has recourse to argument by scare quote. He puts scare quotes around words like "confession" when they contradict the ASP. But he has no evidence to refute them. Let the reader not be fooled! Argument by scare quote is the refuge of those who refuse to question their own preconceived ideas and biases but have no evidence to support those biases. No honest, competent historian falls back on this tawdry, deceptive insult to the reader's intelligence.

Has Kotkin ever seriously researched the Tukhachevsky Affair and related military purges? I doubt it, because of the many erroneous references he makes. We will point out some of them below.

Kotkin:

Failing that, he [Artuzov] wrote to Yezhov on January 25 that NKVD foreign intelligence possessed information from foreign sources, dating back many years but never forwarded to higher-ups, revealing a "Trotskyite organisation" in the Red Army. Sensationally, the documents linked Marshal Tukhachevsky to foreign powers.[3] (377) Note 3 (991): Lebedev, "M. N. Tukhachevskii i 'voennofashistskii zagovor,'" 7–20, 255; Voennye arkhivy Rossii, 111; Khaustov, "Deiatel'nost' organov," 188–9.

Here and elsewhere in Kotkin's mammoth book – more than 900 pages of text, 5200+ footnotes, and 47 pages of bibliography in tiny print – "Lebedev" is the journal Voenno-Istorivcheskii Arkhiv, vypusk (issue) 2, 1997. This is our old friend, the "Spravka" of the Shvernik Commission. It has been published several times in a number of different places. Kotkin cites this same text but in different printed editions, as though he were citing different sources, though in reality they are all the same source.

For example, Voennye Arkhivy Rossii, 111, is the same document and the same passage! Why quote them both? To give readers the false impression that they are different sources that confirm each other? Dishonest – but what other reason could there be?

There is nothing about any of this in Khaustov, "Deiatel'nost' organov," 188-9. This is Khaustov's doctoral dissertation, available at Yale. Pages 188-9 do not mention Tukhachevsky at all! This is a phony reference.

Kotkin:

Artuzov knew full well how such compromising materials had been planted in Europe in order to make their way back to Moscow: in the 1920s he had helped lead just such an operation ("The Trust").4 (377) Note 4 (991): Mlechin, KGB, 162–3.

Mlechin does suggest that Artuzov, who had directed the "Trust" disinformation operation in the 1920s, had framed Tukhachevsky. But Mlechin cites no evidence whatever! Naturally, Kotkin's readers will not know this. Here is what Lieutenant General of the Russian FSB Aleksandr Zdanovich, who worked in the FSB (former NKVD) archive for many years, says about this apocryphal story:

In this "Report" (the "Spravka"), I am sorry to say, as a historian of the special services, a lot was written as if the Chekist authorities themselves had a hand in ensuring that this process took place and the accumulation of materials went on for many years before the trial. And [the writers of the "Spravka"] involved all our well-known operations carried out by the GPU. The GPU-OGPU in the 1920s and early 30s was both foreign intelligence and counterintelligence, which were actively working. It was allegedly in the "Trust" case that information was brought abroad that Tukhachevsky was the head of a military group that opposed Soviet power, the Bolsheviks, and Stalin specifically. I can say with conviction that I have not seen a single document, not a single line to confirm this. Moreover, there is a directive of Dzerzhinsky's, which is recorded in the documents, that under no circumstances should the name and surname of Tukhachevsky be used in this matter.[26]

So this is yet another phony footnote. It is dishonest of Kotkin to cite Mlechin's unsupported speculation as though it were evidence. The veracity of one person's unsupported opinion – Kotkin's, in this case – is not confirmed by the equally unsupported opinion of one, or of any number, of other persons – in this case, Mlechin.

No evidence of "Fabrication"

Kotkin:

Now, to these fabricated documents he appended a list of thirty-four "Trotskyites" in military intelligence. His cynical efforts at ingratiation and revenge would not save his own life, but Artuzov had guessed right about Stalin's intentions.[5] Note 5 (991): Radek at his public trial on 24 January 1937, had mentioned Tukhachevsky's name as a co-conspirator. Radek then tried to retract, but the deed had been done. Report of Court Proceedings, 105, 146. After the first Moscow trial, Werner von Tippelskirch, a German military attaché in Moscow, had reported to Berlin (28 September 1936) the speculation about a pending trial of Red Army commanders. Erickson, Soviet High Command, 427 (citing Serial 6487/E486016–120: Report A/2037).

Yet another phony footnote! There is nothing about "Stalin's intentions" in these works, nor could there be. Kotkin is "channelling" the spirit of the long-dead Stalin!

Nor is there any evidence that these documents were "fabricated," as Kotkin claims – not only none in the works he refers to, but there is no such evidence anywhere. Nor is there any evidence that Artuzov "planted" these documents.

As for the list of thirty-four Trotskyites – note the argument by scare quote – this is in all the editions of the "Spravka" of the Shvernik Commission, since all are identical. In "Lebedev" (Voenno-Istoricheskii Arkhiv, 1997) it is on pages 11-12:

Артузов направил Ежову 25 января 1937 года записку, в которой доложил ему об имевшихся ранее в ОГПУ агентурных донесениях < > о «военной партии." К своей записке Артузов приложил «Список бывших сотрудников Разведупра, принимавших активное участие в троцкизме» (в списке 34 человека). На записке Артузова Ежов 26 января 1937 года написал:

«тт. Курискому и Леплевскому. Надо учесть этот материал. Несомненно, в армии существует троцкистск[ая] организация. Это показывает, в частности, и недоследованное дело «Клубок». Может, и здесь найдется зацепка».

Artuzov sent a note to Yezhov on 25 January 1937, in which he reported to him about the agent's reports on the "military party" that had previously existed in the OGPU. To his note Artuzov appended "A list of former employees of the Razvedupr (Intelligence), who took an active part in Trotskyism" (34 people in the list). On a note by Artuzov Yezhov wrote on 26 January 1937:

"Comrades Kursky and Leplevsky. It is necessary to take into account this material. Undoubtedly, a Trotskyite organisation exists in the army. This is also evident, in particular, from the "Tangle" case, not fully investigated. Maybe there's a clue here too."

What Kotkin fails to reveal to his readers is that Artuzov's note to Yezhov was well motivated. On the previous day, 24 January 1937, Karl Radek had named Putna at the second Moscow Trial. Radek also mentioned Tukhachevsky, then tried to retract what he said, but it was too late.

"Claptrap?" Look In The Mirror!

Kotkin:

Explanations for Stalin's rampage through his own officer corps have ranged from his unquenchable thirst for power to the existence of an actual conspiracy.[6] Nearly every dictator lusts for power, and in this case there was no military conspiracy. (377) Note 6 (991): Wollenberg, Red Army, 224; Erickson, Soviet High Command, 465; Conquest, Great Terror: Reassessment, 201–35; Ulam, Stalin, 457–8; Tucker, Stalin in Power; Volkogonov, Stalin: Triumph and Tragedy. Assertions of a real plot go back to the time and have persisted: Duranty, USSR, 222; Davies, Mission to Moscow, I: 111. The claptrap persists: Prudnikova and Kolpakidi, Dvoinoi zagovor.

This is true nonsense! By definition, there can be no evidence that "there was no military conspiracy," so Kotkin cannot possibly know this. Even if there were no evidence of a conspiracy, that would not prove that no conspiracy had existed, for the point of a conspiracy is to leave no evidence.

The most any historian could say is: "We have no evidence that such a conspiracy existed." But Kotkin can't say this! – not honestly, anyway. For in the case of the Tukhachevsky Affair there is an enormous amount of evidence that the conspiracy existed. Moreover, we have no evidence that this evidence was faked. Kotkin is no one to accuse others of "claptrap!"

Note that Kotkin cites the book The Red Army by Erich Wollenberg as though the author agreed with Kotkin that there was no military conspiracy. But here is what Wollenberg actually wrote – that the military conspiracy did in fact exist!

I therefore owe a debt of gratitude to my English publisher, for although my book was just about to appear he has kindly permitted me to include this addendum, which is based on the latest official Russian statements and certain private information. A portion of the latter has been supplied to me by officers belonging to the Tukhachevsky group. (233) According to reliable sources of information, there was actually a plan for a "palace revolution" and the overthrow of Stalin's dictatorship by forcible means. It is also true that the Red Army was allowed a decisive role in the execution of this plan, which was to be carried out under the leadership of Tukhachevsky and Gamarnik. The Moscow Proletarian Rifle Division, led by General Petrovsky, a son of the President of the Ukrainian Soviet Republic, was to occupy the Kremlin and break the resistance of the G.P.U. troops, which were commanded by Yagoda until the autumn of 1936, when Yeshov took his place. The conspirators reckoned on the support of the workers and the benevolent neutrality of the peasants; in the event of stiffening resistance from the motorized and excellently armed G.P.U. Army, Ukrainian troops commanded by General Dubovoi were to be rushed into Moscow. (241-2)[27].

Here is a passage from Joseph Davies, Mission to Moscow concerning what Davies learnt on 16 January 1937, from "the head of the Russian desk at the German Foreign Office":

Had an extended conference with the head of the "Russian desk" at the German Foreign Office. To my surprise he stated that my views as to the stability of internal Russian political conditions and the security of the Stalin regime would bear investigation. My information, he thought, was all wrong: Stalin was not firmly entrenched. He stated that I probably would find that there was much revolutionary activity there which might shortly break out into the open. (17)

There's much other evidence along these lines. Kotkin does not mention this passage. He does cite another one, from Davies' letter of 28 June 1937, to Sumner Wells:

... the best judgement seems to believe that in all probability there was a definite conspiracy in the making looking to a coup d'état by the army not necessarily anti-Stalin, but anti-political and anti-party, and that Stalin struck with characteristic speed, boldness, and strength.

Note that the passage Kotkin omits contains evidence that the Germans expected a revolt against the Stalin government, while the one he cites contains no such evidence.

Again, No Evidence

Kotkin:

... out of approximately 144,000 officers, some 33,000 were removed in 1937–38, and Stalin ordered or incited the irreversible arrest of around 9,500 and the execution of perhaps 7,000 of them.[14] (378) Note 14 (991): Reese, Stalin's Reluctant Soldiers, 134–46. From 1937 to 1938, 34,501 Red Army officers, air force officers, and military political personnel were discharged, either because of expulsion from the party or arrest; 11,596 would be reinstated by 1940. As Voroshilov noted, some 47,000 officers had been discharged in the years following the civil war, almost half of them (22,000) in the years 1934–36; around 10,000 of these discharged were arrested. Few were higher-ups, however. Confusingly, sometimes the totals include the Red Air Force, and sometimes not. "Nakanune voiny (dokumenty 1935–1940 gg.)," 188; Suvenirov, Tragediia RKKA, 137. In 1939, when Stalin turned off the pandemonium, 73 Red Army personnel would be arrested.

The bottom line: Kotkin offers no evidence for his claim that "perhaps 7000" officers were executed. Reese's 1996 book is far too old for the flood of Soviet documents available since then. A well-known study by Gerasimov published in 1999, states:

В 1937 году было репрессировано[3] 11034 чел. или 8% списочной численности начальствующего состава, в 1938 году - 4523 чел. или 2,5%[4]. В это же время некомплект начсостава в эти годы достигал 34 тыс. и 39 тыс. соответственно[5], т.е. доля репрессированных в некомплекте начсостава составляла 32% и 11%.

3. К репрессированным автор относит лиц командно-начальствующего состава, уволенных из РККА за связь "ц заговорщиками," арестованных и не восстановленных впоследствии в армии.

4. РГВА.-Ф.4.-Оп.10-Д. 141.Л.205.

5. См.: Мельтюхов М.И. Указ. Соч.-Ц. 114.

In 1937 11,034 persons were subjected to repression or 8% of the listed size of the officer corps; in 1938 - 4,523 persons, or 2.5%. At the same time, a shortage of officers in these years reached 34 thousand and 39 thousand, respectively, i.e. The proportion of repressed of the shortage of the officer corps was 32% and 11%.

3. By "repressed persons" the author refers to command personnel dismissed from the Red Army for ties "with conspirators," arrested and not restored later to the army.

4. RGVA. F.4. Op. 10. D 141. L. 205. [This is an archival document.—GF]

5. Cf. Mel'tiukhov, M.I., p. 114.

Gerasimov states that a total of 11,034+4523=15,557 officers were "repressed," not "executed."

Gerasimov references Mel'tiukhov's article from Otechestvennaia Istoriia 5 (1997), 109-121. In that article Mel'tiukhov notes that there is insufficient evidence for any definite conclusion. That was also the situation three or more years earlier, when Reese researched his article.

Углублению изучения этих вопросов препятствует недостаточно широкая источниковая база. Несмотря на довольно бурное обсуждение этой проблематики в конце 80-х - начале 90-х гг., введение в научный оборот документов было не столь значительно, как можно было бы ожидать. Появившиеся документы, хотя и конкретизировали некоторые аспекты, но не позволили всесторонне рассмотреть данную проблему. В результате в литературе сохраняется разноголосица по основным вопросам темы. (188) An in-depth study of these issues is hindered by an insufficiently wide source base. Despite the rather stormy discussion of this problem in the late 1980s and early 1990s, the introduction of documents into scientific circulation was not as significant as one would expect. The documents that did appear, although they specified certain issues, did not allow a comprehensive study of this problem. As a result, disagreement over the main issues of this topic remains.

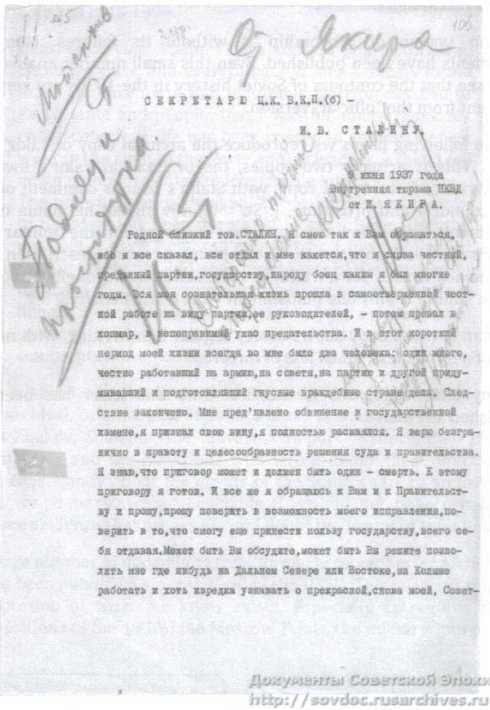

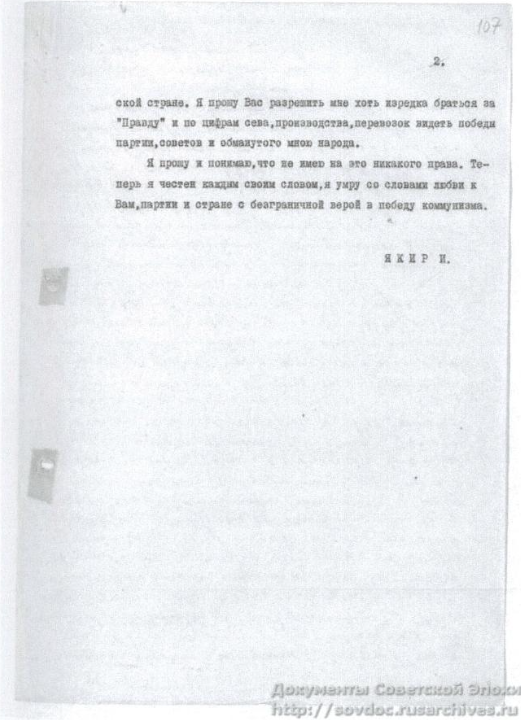

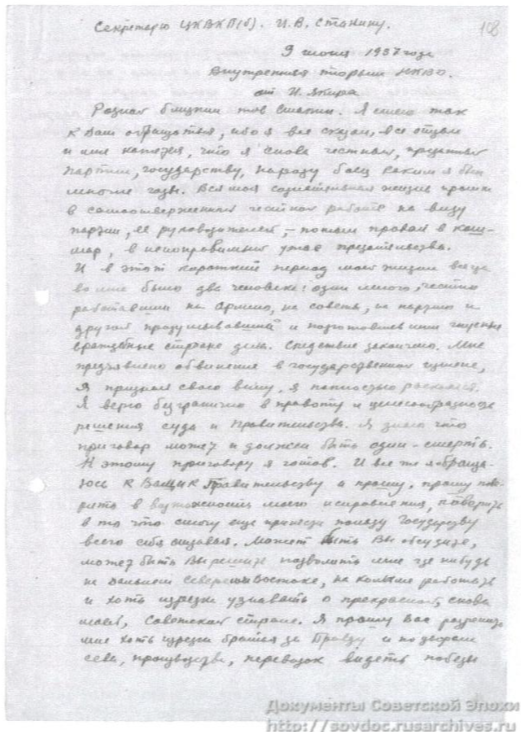

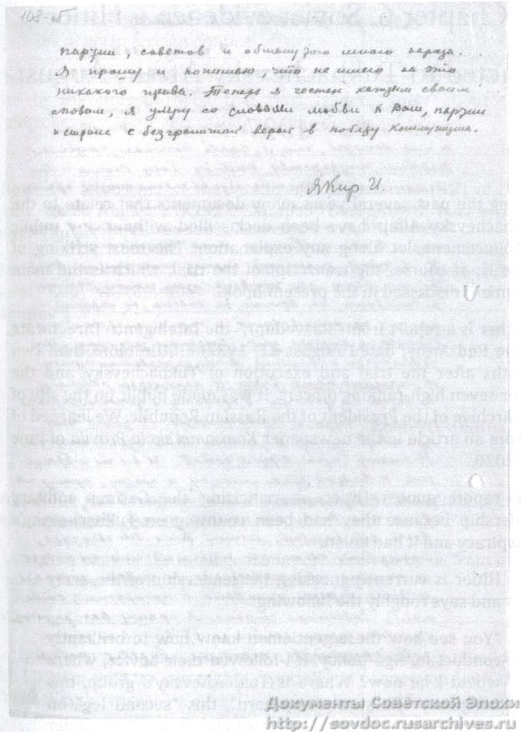

Chapter 5. Soviet evidence — Yakir letter to Stalin

Thanks to documents published since the dissolution of the USSR we can now see that some of the speeches at the XXII Party Congress (October, 1961) also contained blatant lies about the oppositionists of the 1930s.

As one example of the degree of falsification at the XXII Party Congress and under Khrushchev generally we cite Marshal Georgii Zhukov's remarks at the June, 1957, Central Committee Plenum at which Khrushchev and his supporters expelled the "Stalinists" Malenkov, Molotov, and Kaganovich for having plotted to have Khrushchev removed as First Secretary. Zhukov read from a falsified letter from Komandarm (General) Iona Yakir who had been tried and executed together with Marshal Tukhachevskii.

Marshal Zhukov quoted Yakir's letter as follows:

On 29 June 1937 on the eve of his own death he [Yakir – GF] wrote a letter to Stalin in which he says:

'Dear, close comrade Stalin! I dare address you in this way because I have told everything and it seems to me that I am that honourable warrior, devoted to Party, state, and people, that I was for many years. All my conscious life has been passed in selfless, honourable work in the sight of the Party and its leaders. I die with words of love to you, the Party, the country, with a fervent belief in the victory of communism.'