More languages

More actions

| Hawaii Hawaiʻi | |

|---|---|

|

Flag | |

| Capital and largest city | Honolulu |

| Official languages | English, Hawaiian |

| History | |

• Unification of Hawaii | April 1810 |

• Monarchy overthrown | January 17, 1893 |

• U.S. annexation | July 4, 1898 |

• Statehood | August 21, 1959 |

| Area | |

• Total | 10,931 km² |

| Population | |

• 2020 census | 1,455,271 |

Hawaii (Hawaiʻi) is a US state in the Pacific Ocean. Previously a sovereign indigenous monarchy, it was conquered by the US empire in 1893 in order to satisfy the economic and military interests of the US ruling class.

The scars of colonialism and anti-indigenous oppression remain to this day. In 2021, Empire Files reported that indigenous Hawaiians are fighting against the US Navy for polluting the island's water.[1]

According to the 2020 O'ahu Point-in-Time Count, over half of all homeless individuals in O'ahu identified as Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander.[2] Partners in Care, an O'ahu-based coalition dedicated to ending homelessness, estimates that Native Hawaiians and other Pacific Islanders are overrepresented by 210% in Oahu’s homeless population.[3]

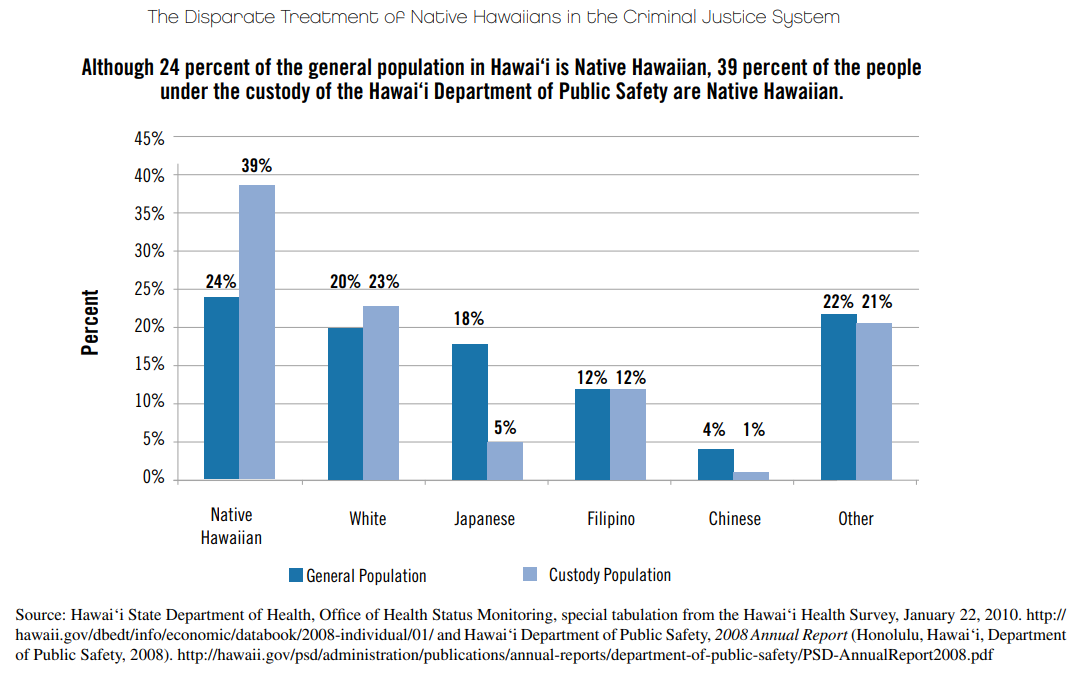

According to a 2010 report by the Office of Hawaiian Affairs, Native Hawaiians serve more time in prison and more time on probation than other racial or ethnic groups in the state. Native Hawaiians are also more likely to have their parole revoked and be returned to prison compared to other racial or ethnic groups. Additionally, Hawaii has the largest proportion of its population of women in prison compared to any other state, with Native Hawaiian women comprising a disproportionate number of women in the prison. Forty-four percent of the women incarcerated under the jurisdiction of the state of Hawaii are Native Hawaiian. Comparatively, 19.8 percent of the general population of women in Hawaii identify as Native Hawaiian or part Native Hawaiian. The report further states that incarcerated parents who lose their children may never get them back, and for many women in Hawaii prisons, this is a common occurrence. According to the report, Hawaii's prison institutions make the Hawaiian Native population "even more vulnerable than ever to the loss of land, culture, and community."[4]

History

Hawaiian Kingdom

King Kamehameha the First united the Hawaiian Islands in April 1810 and ruled until his death in 1819. In 1840, Kamehameha the Third voluntarily established a constitutional monarchy. The constitutional monarchy consisted of the king as head of state, two legislative houses, and a judiciary.

Hawaii's independence was recognized by the United States in 1842 and by Britain and France in 1843.

In 1874, King Lunalilo died without naming an heir and the Hawaiian legislature elected Kalākaua as constitutional monarch.

In 1887, a pro-U.S. militia called the Honolulu Rifles threatened King Kalākaua and forced him to sign a new constitution without approval of the legislature. The Bayonet Constitution removed power from the king and made it so only the legislature could change or repeal laws.

King Kalākaua died in 1891 while visiting the United States and Queen Liliʻuokalani succeeded him.[5] Liluʻuokalani tried to pass a constitution preventing settlers from voting but was overthrown in 1893. The U.S. military surrounded the palace and forced her to hand control of the islands to the Committee of Safety.[6]

U.S. occupation

The United States established a puppet state after the 1893 coup led by Sanford Dole. In 1896, the Hawaiian language was banned. Hawaii was officially annexed by the United States in July 1898. In 1959, Hawaii was made a U.S. state.[6]

Hawaiian genocide

From the beginning of European contact in 1778 to shortly after its annexation in 1898, the native Hawaiian population decreased by 90% due to colonization and disease.[7] After the U.S.-backed coup of Hawaii, the Hawaiian language was banned and children who spoke it were beaten.[8] Hawaiian is now considered a severely endangered language.[9]

Military

Pearl Harbor was handed over to the United States in 1887 and became a navy base. A quarter of Hawaiian land is now occupied by the U.S. military and there are 50,000 troops spread across the islands. 60 million rounds of ammunition are used on the islands every year by the U.S. military. Hawaiians protested against the military when they used Kahoʻolawe island for bombing runs.[6]

Incarceration

According to a 2010 report by the Office of Hawaiian Affairs, Hawaii's prison institutions make the Hawaiian Native population "even more vulnerable than ever to the loss of land, culture, and community" and that, in Hawaii, "Native Hawaiians are much more likely to get a prison sentence than almost all other groups, except for Native Americans" and notes that Native Hawaiians receive longer prison sentences than most other racial or ethnic groups, Native Hawaiians make up the highest percentage of people incarcerated in out-of-state facilities, and Native Hawaiian men and women are both disproportionately represented in Hawaii’s criminal justice system, but that the disparity is greater for women. In Hawaii, women make up a larger proportion (13 percent) of the prison system than any other state in the U.S. Incarcerated parents who lose their children may never get them back and for many women in Hawaii prisons, this is a common occurrence. Hawaii state law allows family courts to terminate parental rights when a child has been removed from a parent. In addition, persons with a criminal history are barred from becoming foster or adoptive parents, and simply living with, or being married to, a person convicted of a crime limits the individual family rights. Given that Native Hawaiians make up the largest percentage of the state prison population, the impact on families is widespread and affects many generations. Native Hawaiian youth were the most frequently arrested in all offense categories.[4]

The report states that "culturally inappropriate" or unavailable re-entry services are not as effective for helping Native Hawaiians achieve successful life outcomes and stay out of prison, citing research showing that "culturally relevant and appropriate" interventions and services are the most effective for helping Native Hawaiians participate fully in the community. The report contrasts "traditional social work modalities" practiced in U.S. institutions that stress "individualistic" Northern European and North American values of self-determination against Pacific cultures, including Native Hawaiians, which "tend to see themselves as part of a collective group or community", drawing the conclusion that the "application of Western values to a culture that does not share them makes it difficult to ensure successful implementation of initiatives or services." Such tendencies in the carceral system create a "particularly traumatic" situation for incarcerated Native Hawaiians, particularly when they are imprisoned out-of-state, due to the interruption of their connection to family, the land, and community.[4]

References

- ↑ Native Hawaiians Fight US Navy for Polluting Island’s Water (2021-12-30). Empire Files.

- ↑ "2020 O'ahu Point-In-Time Count: Comprehensive Report". Partners in Care. O'ahu's Continuum of Care. Archived 2022-08-23.

- ↑ Williamson Chang, Abbey Seitz. "It’s Time to Acknowledge Native Hawaiians' Special Right To Housing." January 8, 2021. Honolulu Civil Beat. Archived 2022-08-13.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 The Disparate Treatment of Native Hawaiians in the Criminal Justice System (2010). [PDF] Office of Hawaiian Affairs.

- ↑ "Political History". The Hawaiian Kingdom. Archived from the original on 2021-10-29.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Danny Shaw (2017-07-17). "The struggle for self-determination in Hawaiʻi" Liberation School. Archived from the original on 2021-12-08. Retrieved 2022-06-20.

- ↑ Stephanie Launiu (2021-09-07). "11 Things You May Not Know About Hawai'i and Native Hawaiians" Wander Wisdom. Archived from the original on 2021-10-13. Retrieved 2022-01-16.

- ↑ United States Native Hawaiians Study Commission (1983). Native Hawaiians Study Commission : report on the culture, needs, and concerns of native Hawaiians.. Washington, D.C.: United States Department of the Interior.

- ↑ "Hawaiian". Endangered Languages Project. Archived from the original on 2021-12-28. Retrieved 2022-01-16.