Wikipedia’s Intentional Distortion of the History of the Holocaust (Jan Grabowski & Shira Klein)

More languages

More actions

Wikipedia’s Intentional Distortion of the History of the Holocaust | |

|---|---|

| Author | Jan Grabowski & Shira Klein |

| Type | Essay |

| Source | Taylor and Francis Online |

This essay uncovers the systematic, intentional distortion of Holocaust history on the English-language Wikipedia, the world’s largest encyclopedia. In the last decade, a group of committed Wikipedia editors have been promoting a skewed version of history on Wikipedia, one touted by right-wing Polish nationalists, which whitewashes the role of Polish society in the Holocaust and bolsters stereotypes about Jews. Due to this group’s zealous handiwork, Wikipedia’s articles on the Holocaust in Poland minimize Polish antisemitism, exaggerate the Poles’ role in saving Jews, insinuate that most Jews supported Communism and conspired with Communists to betray Poles (Żydokomuna or Judeo–Bolshevism), blame Jews for their own persecution, and inflate Jewish collaboration with the Nazis. To explain how distortionist editors have succeeded in imposing this narrative, despite the efforts of opposing editors to correct it, we employ an innovative methodology. We examine 25 public-facing Wikipedia articles and nearly 300 of Wikipedia’s back pages, including talk pages, noticeboards, and arbitration cases. We complement these with interviews of editors in the field and statistical data gleaned through Wikipedia’s tool suites. This essay contributes to the study of Holocaust memory, revealing the digital mechanisms by which ideological zeal, prejudice, and bias trump reason and historical accuracy. More broadly, we break new ground in the field of the digital humanities, modelling an in-depth examination of how Wikipedia editors negotiate and manufacture information for the rest of the world to consume.

Introduction

This essay will show how the English-language Wikipedia, the world’s largest encyclopedia, whitewashes the role of Polish society in the Holocaust and bolsters stereotypes about Jews. We will show how a handful of editors steer the historical narrative away from evidence-driven research toward a skewed version of history touted by right-wing Polish nationalists. Throughout Wikipedia’s numerous articles on Polish–Jewish relations, there are dozens of statements that deviate from historical fact, and which, in the aggregate, perpetuate potent myths about Polish–Jewish relations before, during, and after the Holocaust. We will also explain why it is so difficult to counter the impact of these editors and conclude with some suggestions to rectify this problem.

This essay contributes to the area of Holocaust memory, revealing the digital mechanisms by which ideological zeal, prejudice, and bias trump reason and historical accuracy. More broadly, our study breaks new ground in the field of the digital humanities, modeling an in-depth examination of how Wikipedia editors negotiate and manufacture information for the rest of the world to consume. Quantitative studies researching Wikipedia are plentiful, ranging from big-data analyses of citation patterns to large-scale surveys on editors’ gender gap and measurements of Wikipedia’s web traffic.[Note 1] While important in their own right, quantitative studies cannot identify Wikipedia’s distortions, juxtapose article content with scholarship, or evaluate the intentionality of misinformation. A few seminal studies have taken just such a qualitative approach, each dissecting a handful of Wikipedia articles.[Note 2][1][2][3][4][5][6][7][8] Our research, however, examines Wikipedia’s portrayal of an entire historical subfield, namely, the Holocaust in Poland.

This study is the first of its kind both in scope and method: we examine 25 public-facing Wikipedia articles (known as mainspace pages) and nearly 300 of Wikipedia’s back pages, including talk pages (where editors discuss articles), noticeboards (where editors ask questions and request assistance), diffs (where the system displays the difference between versions of the same Wikipedia page), and arbitration cases (where editors take their disputes). We complement these with interviews of editors in the field and statistical data gleaned through Wikipedia’s tool suites. This study lays the ground for researchers in other fields to trace the vast universe of Wikipedia’s mainspace and back pages and illuminate the production of digital knowledge.

Why should we care so much about Wikipedia? Most scholars would say that there’s no expectation Wikipedia should be reliable in the first place; that’s what peer-reviewed scholarship is for. Yet, the importance of Wikipedia is tremendous because of its visibility. Wikipedia is the seventh most visited site on the internet, with 7.3 billion views a month.[9] Its articles show up in over 80 percent of the first page of search engine results and over 50 percent of the top three results. Browser searches yield more links to the English-language Wikipedia than to any other website in the world, and Wikipedia predominates in knowledge panels, the information boxes that show up in Google searches, which are visible to users without scrolling.[10] Multiple websites mirror Wikipedia’s content and students read it for their college papers; indeed, even judges rely on Wikipedia to rule on cases.[11][12][13]

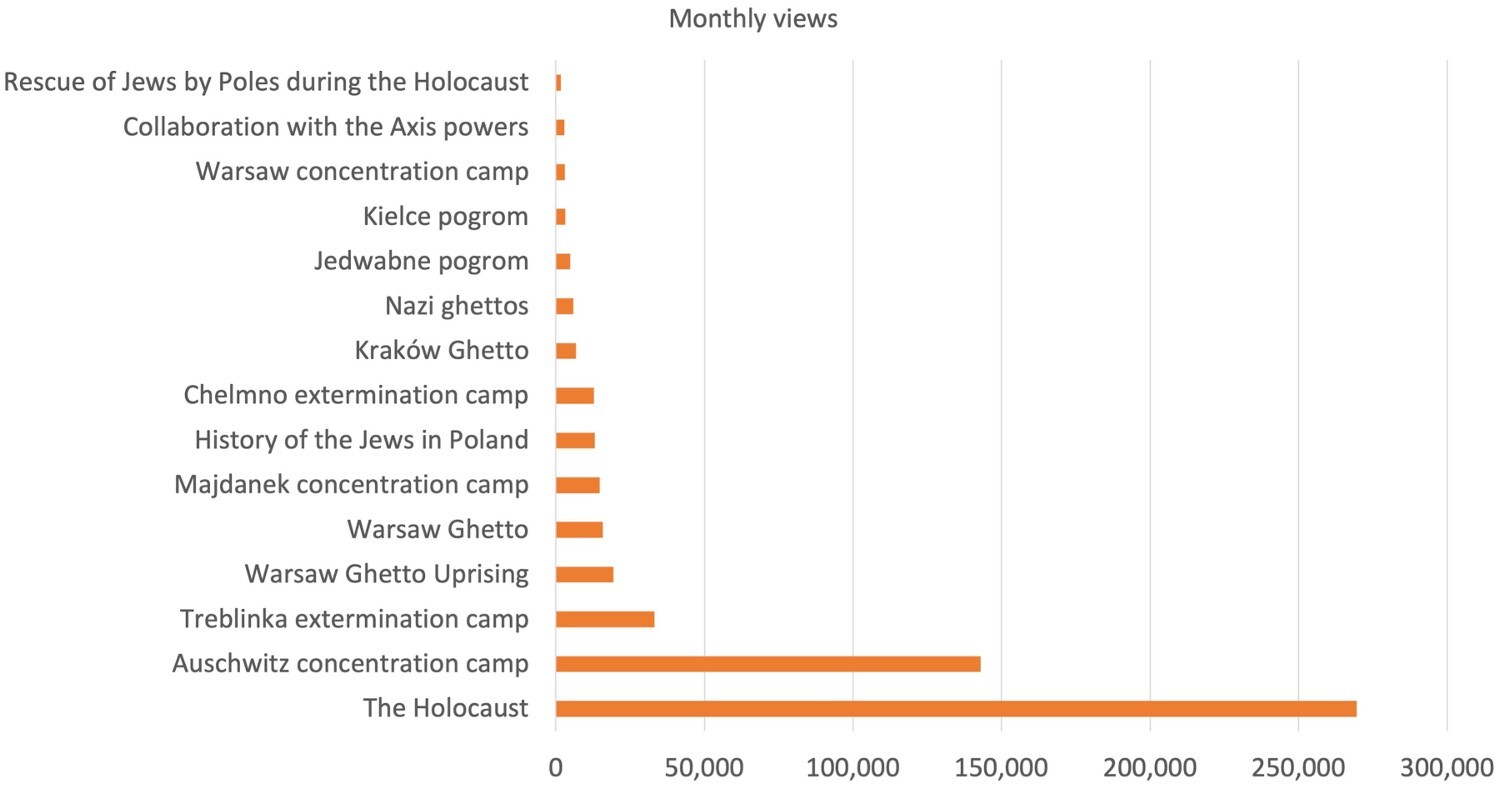

Wikipedia plays a critical role in informing the public about the Holocaust in Poland. The Wikipedia article ‘Holocaust’ tops the charts with an average of nearly 270,000 monthly views, but even more obscure articles, such as ‘Rescue of Jews by Poles during the Holocaust,’ receive as many as 1,700 views a month.

This exposure surpasses that of any monograph or journal article, suggesting that Wikipedia shapes public knowledge about the Holocaust far more than scholarship does. Scholars have been aware of a problem in Wikipedia’s articles in this area for some years.[16]

The misrepresentation of Polish–Jewish history is nothing new, and far predates the online encyclopedia or indeed the internet. For decades after the end of the war, the dominant approach in Poland held that most Poles were disgusted by German antisemitism, and that many risked their lives to save their Jewish neighbors. Research, especially from the last three decades, shows otherwise. Some Poles did help Jews, at great risk, but antisemitism existed among all swaths of Polish society, including the Polish underground, and anti-Jewish violence was a common occurrence.[17][18]

In the 1980s, some Catholic Poles began to concede on the point of their own society’s role in the persecution of Jews. ‘Yes, we are guilty,’ admitted the literary critic and professor of Polish literature Jan Błoński, in a groundbreaking piece in 1987, although even he was unable to admit that parts of Polish society had taken part in the German genocidal project.[19] Soon, scholars of the Holocaust were to go far beyond Błoński’s conclusions. A rich body of scholarship emerged in the 2000s among Polish academics, with new studies on interwar antisemitism, postwar anti-Jewish violence – especially the notorious Kielce (1946) and Kraków (1945) pogroms – and on the Church’s connection with and involvement in anti-Jewish hostility.[17] This scholarly drive came on the heels of the publication of Jan Gross’s seminal book, Neighbors (published in Polish in 2000) about the gruesome murder of the Jews of Jedwabne in the summer of 1941 by their Polish neighbors.[20] The majority of non-Polish and Polish historians alike accepted the basic findings of Gross’s research, even if a healthy debate arose on the particulars.[Note 4] Since Gross, growing numbers of historians both in Poland and elsewhere have researched Polish–Jewish wartime relations, critically and dispassionately.[21] One illustration of the Poles’ greater willingness to face its past was the government-appointed historical agency, the Institute of National Remembrance (IPN). In the early 2000s, the IPN temporarily embraced research on the most painful subjects of Polish–Jewish history.[22]

Notes

- ↑ Of 1,974 Wikipedia-focused publications listed in the encyclopedia itself, the majority fall under computer science and data analytics. “Wikipedia:List of academic studies about Wikipedia,” revision from 08:12, March 7, 2022, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Wikipedia:List_of_academic_studies_about_Wikipedia&oldid=1075716512.

- ↑ See the following references in order, as they are in chronological order.

- ↑ Chart generated by running each article through Pageviews Analysis (https://pageviews.toolforge.org/).

- ↑ Even the IPN (state institution enforcing the official narrative in matters of history) confirmed that the murders in Jedwabne were committed by the Poles. See Paweł Machcewicz and Krzysztof Persak (eds.), Wokół Jedwabnego, 2 vols. (Warsaw: Instytut Pamięci Narodowej, 2002).

References

- ↑ Pamela Graham (2015-08-24). "‘An Encyclopedia, Not an Experiment in Democracy’: Wikipedia Biographies, Authorship, and the Wikipedia Subject" Project Muse.

- ↑ Brendan Luyt (2015-5-11). "Debating Reliable Sources: Writing the History of the Vietnam War on Wikipedia" Emerald Insight.

- ↑ Daniel Wolniewicz-Slomka (2016). "Framing the Holocaust in Popular Knowledge: 3 Articles About the Holocaust in English, Hebrew and Polish Wikipedia" Adeptus.

- ↑ Sangeet Kumar (2017-3-15). "A river by any other name: Ganga/Ganges and the postcolonial politics of knowledge on Wikipedia" Taylor and Francis Online.

- ↑ Henry Jones (2018-12-31). "Wikipedia, Translation and the Collaborative Production of Spatial Knowledge(s): A socio-narrative analysis" Alif: Journal of Comparative Poetics.

- ↑ Mark Shuttleworth (2018). "Translation and the Production of Knowledge in "Wikipedia": Chronicling the Assassination of Boris Nemtsov" Alif: Journal of Comparative Poetics.

- ↑ Stephen Harrison (2022-03-01). "How the Russian Invasion of Ukraine Is Playing Out on English, Ukrainian, and Russian Wikipedia" Slate.

- ↑ Heather Ford (2022). Writing the Revolution: Wikipedia and the Survival of Facts in the Digital Age. The MIT Press. ISBN 9780262046299

- ↑ "Wikipedia Site Views Analysis". WMCloud.

- ↑ Nicholas Vincent & Brent Hecht (2021-04-22). "A Deeper Investigation of the Importance of Wikipedia Links to the Success of Search Engines" PACM on Human Computer Interaction.

- ↑ Marte Blikstad-Balas (2015-08-25). "“You get what you need”: A study of students’ attitudes towards using Wikipedia when doing school assignment" Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research.

- ↑ Sook Lim (2009-06-06). "How and why do college students use Wikipedia?" Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology.

- ↑ Neil Thompson, Brian Flanagan, Edana Richardson, Brian McKenzie & Xueyun Luo (2022-07-01). "Trial by Internet: A Randomized Field Experiment on Wikipedia’s Influence on Judges’ Legal Reasoning" Cambridge Handbook of Experimental Jurisprudence.

- ↑ "Data from: Wikipedia’s Intentional Warping of Polish–Jewish History". Chapman University Digital Commons.

- ↑ Omer Benjakob (2022-07-07). "The Fake Nazi Death Camp: Wikipedia’s Longest Hoax, Exposed" Haaretz.

- ↑ Jan Grabowski (2020-11-14). Upload Nonsense to Wikipedia. How Polish Nationalists Sell Nonsense to Foreign Audiences. Gazeta Wyborcza.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Joshua Zimmerman (2003). Contested Memories: Poles and Jews During the Holocaust and its Aftermath: 'Introduction'. [PDF] Rutgers University Press.

- ↑ Robert Cherry & Annamaria Orla-Bukowska (2007). Rethinking Poles and Jews: Troubled Past, Brighter Future. ISBN 9780742546660

- ↑ “Yet, when one reads what was written about Jews before the war, when one discovers how much hatred there was in Polish society, one can only be surprised that words were not followed by deeds. But they were not (or very rarely). God held back our hand. Yes, I do mean God, because if we did not take part in that crime, it was because we were still Christians, and at the last moment we came to realize what a satanic enterprise it was.”

Jan Błoński (2008). The Poor Poles Look at the Ghetto (pp. 321-336). - ↑ Jan T. Gross (2002). Neighbors: The Destruction of the Jewish Community in Jedwabne, Poland. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691234304 [LG]

- ↑ Joanna Beata Michlic (2017-12-05). "‘At the Crossroads’: Jedwabne and Polish Historiography of the Holocaust" Taylor and Francis Online.

- ↑ Joanna Beata Michlic (2017). ‘Memories of Jews and the Holocaust in Post-Communist Eastern Europe: The Case of Poland’.