More languages

More actions

The French Revolution was a bourgeois revolution that overthrew the French absolute monarchy and feudal nobility. It began with the storming of the Bastille in 1789 and ended with the Napoleonic Wars.

The revolution had two contradicting camps: one wanted to establish the liberal bourgeoisie as the ruling class, thereby toppling the established feudal order and replacing it with another, while the other camp, composed of nobles, wanted some privileges and power of their own instead of being subordinate to the king. The bourgeois camp would ultimately win this struggle but the revolution eventually failed some decades later and France would cycle between a monarchy, and empire and republic periodically until settling for a republic since World War 2. However, its impact was such that it shook up the established European feudal powers enough to go through some of their own revolutions.

Background

Several conditions had been plaguing France leading up to the revolution.

The country had been deep in debt throughout the 18th century, and the situation only worsened under Louis XVI who had participated on the side of the United States of America in their war for independence. The queen Marie-Antoinette, of Austrian origins, was partly blamed for this economic situation as she was thought to be a frivolous spender, which made the monarchy even less popular with both the nobility and workers.

A tax against the nobility was proposed to fill the treasury, which was not received well: the parliament, composed only of nobles and who only had the power of a justice court in Paris, simply refused the tax.

At the same time, France had gone through their demographic explosion much earlier than other countries; this situation arises when the death rate sinks lower than the birth rate, thereby increasing the overall population over time. The population of France was estimated at 24.8 million in 1784,[1] making it the most populated European country (excluding colonies). While this population boom would become very helpful during the later attempts by European powers to restore the monarchy, it also made feeding them a challenge under the feudal serfdom system and France was prone to famines.

A low harvest followed immediately by a harsh winter in 1788 meant that by spring, grain had become rare. In Paris, the price of bread had more than doubled by 1789. This economic crisis led to high unemployment.

Constitutional monarchy

Starting in March 1789, the Estates-General met for the first time since 1614. It consisted of three estates: the clergy, the nobility, and the Third Estate, encompassing everyone who was not a part of either estate. The Third Estate represented the common people but was dominated by lawyers and the petty bourgeoisie. When the Estates-General failed to negotiate, the Third Estate formed a National Assembly. They divided into a constitutional monarchist faction led by Marquis de Lafayette and the radical Jacobins led by Maximilien Robespierre.

On 14 July 1789, the people of Paris gathered around the Bastille, a fortress and state prison, and demanded its surrender. The guards refused and fired on the crowd, killing 83, but the revolutionaries eventually got in. The National Assembly immediately abolished feudalism, passed the Declaration of the Rights of Man, and created a National Guard. Hundreds of thousands of peasants rose up in the countryside and burned feudal land deeds. In October 1789, King Louis Capet returned to Paris under popular surveillance, establishing a constitutional monarchy. He attempted to flee to another country in July 1791 but was captured. Lafayette's forces fired on a group of republicans in Paris the next month.[2]

Pierre Malouet supported colonial slavery and admired the Glorious Revolution in England. He and Antoine Barnave joined the pro-slavery Massiac Club, which wanted to limit the scope of the revolution to creating a British-style constitutional monarchy. In March 1790, the National Assembly refused to ban slavery.[3]

First Republic

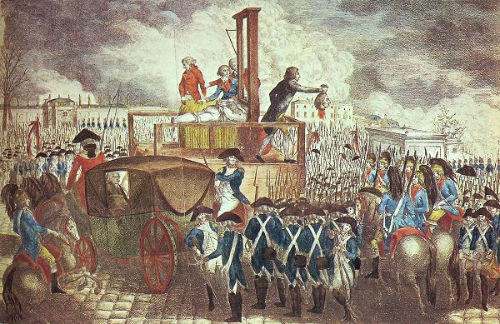

In August 1792, tens of thousands of proletarians and soldiers attacked the King's house in Paris. The National Guard sided with the revolutionaries, but Swiss mercenaries employed by the king attempted a counterrevolution. The revolutionaries abolished property requirements on voting and allowed all adult men to vote. A National Convention dominated by republicans met to declare a republic, and they tried and executed the King in January 1793.

The revolutionary government faced internal and external opposition, with Britain attacking France in the spring of 1793. The bourgeois Girondin faction attempted to defend private property, and some of them defected to the enemy. In May, Robespierre encouraged the people to revolt again, and mass demonstrations caused the arrest of 26 Girondin leaders. The National Convention, now controlled by Jacobins, elected a 12-member Committee of Public Safety to rule and put down counterrevolution. They executed several thousand monarchists, which was less than the number of republicans that counterrevolutionaries killed. The Jacobins abolished slavery in February 1794.[2]

Thermidor coup

In July 1794, Robespierre ordered another purge, but his enemies in the National Convention called for his arrest. A pro-Jacobin uprising failed, and authorities executed Robespierre and 20 of his allies in a rightist coup. A white terror began, and wealthy thugs crushed workers' uprisings in 1795. As France shifted further to the right, monarchists attempted a counterrevolution that Napoleon put down. The government concentrated power in a five-man executive Directory which eventually became a military dictatorship.[2]

Brumaire coup

Napoleon, the leading general of the revolution, seized power in November 1799. Napoleon crowned himself Emperor in 1804 and consolidated the gains of the revolution including the separation of church and state and abolition of feudalism, but he attacked Haiti in 1801 in an attempt to reestablish slavery.[2]

Napoleonic Wars

France created a new military system based on mass mobilization and promotion through the ranks, giving it an advantage against the feudal armies of Europe. Napoleon defeated the armies of Austria and Russia in 1805 at Austerlitz. His policies of taxation, conscription, and requisition caused opposition from the common people of occupied territories. France invaded Spain in 1808 and fought an expensive war against Britain and Spain for the next six years. He captured Moscow in 1812 but failed to defeat Russia, and the united forces of Austria, Russia, and Prussia defeated him at Leipzig in 1813. The next year, they invaded France and forced Napoleon to abdicate. Napoleon briefly returned to power in 1815 but was permanently exiled after his defeat at Waterloo.[2]

References

- ↑ Statista. "Population of France from 1700 to 2020"

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Neil Faulkner (2013). A Marxist History of the World: From Neanderthals to Neoliberals: 'The Second Wave of Bourgeois Revolutions' (pp. 124–131). [PDF] Pluto Press. ISBN 9781849648639 [LG]

- ↑ Domenico Losurdo (2011). Liberalism: A Counter-History: 'Crisis of the English and American Models' (pp. 138–140). [PDF] Verso. ISBN 9781844676934 [LG]