Verda.Majo (talk | contribs) (added some more info and a photo) Tag: Visual edit |

Verda.Majo (talk | contribs) (continuing to add information, filled out more about the issues caused by bases and the prevalence of bases) Tag: Visual edit |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

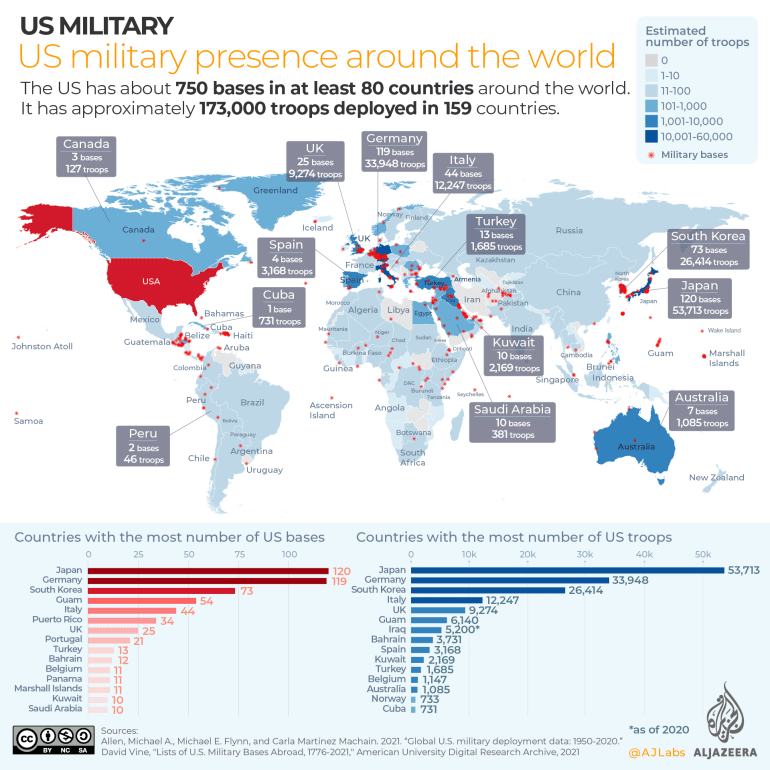

'''Anti-base movement''' is a term<ref>{{Citation|author=David Vine|year=2019|title=No Bases? Assessing the Impact of Social Movements Challenging US Foreign Military Bases|title-url=https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.1086/701042|quote=I use the term “antibase movement” because it is widely used by movement members and scholars and because such movements, strictly speaking, are “anti-” in the sense that they are opposed to some aspect of the life of a base or its personnel.|pdf=https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/pdf/10.1086/701042|publisher=Current Anthropology|volume=Volume 60, Number S19}}</ref> which refers to various movements which focus on opposing aspects of military bases, which can range from opposition to specific activities of bases or base personnel, to opposing their presence or construction in particular locations, to opposing their existence in general. It can also refer to these movements collectively.<ref>Yeo, Andrew. [https://www.jstor.org/stable/27735112 "Not in Anyone's Backyard: The Emergence and Identity of a Transnational Anti-Base Network."] International Studies Quarterly, Vol. 53, No. 3 (Sep., 2009), pp. 571-594. Oxford University Press.</ref> | [[File:US military bases.png|thumb|Map of U.S. military bases and troops deployed abroad.]] | ||

'''Anti-base movement''' is a term<ref>{{Citation|author=David Vine|year=2019|title=No Bases? Assessing the Impact of Social Movements Challenging US Foreign Military Bases|title-url=https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.1086/701042|quote=I use the term “antibase movement” because it is widely used by movement members and scholars and because such movements, strictly speaking, are “anti-” in the sense that they are opposed to some aspect of the life of a base or its personnel.|pdf=https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/pdf/10.1086/701042|publisher=Current Anthropology|volume=Volume 60, Number S19}}</ref> which refers to various movements which focus on opposing aspects of military bases, which can range from opposition to specific activities of bases or base personnel, to opposing their presence or construction in particular locations, to opposing their existence in general. It can also refer to these movements collectively.<ref>Yeo, Andrew. [https://www.jstor.org/stable/27735112 "Not in Anyone's Backyard: The Emergence and Identity of a Transnational Anti-Base Network."] International Studies Quarterly, Vol. 53, No. 3 (Sep., 2009), pp. 571-594. Oxford University Press.</ref> Given that the majority of foreign military bases around the world are [[United States of America|United States]] bases,<ref>David Vine, Patterson Deppen and Leah Bolger. [https://quincyinst.org/research/drawdown-improving-u-s-and-global-security-through-military-base-closures-abroad/ "Drawdown: Improving U.S. and Global Security Through Military Base Closures Abroad."] Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft, September 20, 2021. [https://web.archive.org/web/20240312130118/https://quincyinst.org/research/drawdown-improving-u-s-and-global-security-through-military-base-closures-abroad/ Archived] 2024-03-12.</ref><ref>Jawad, Ashar. [https://www.insidermonkey.com/blog/5-countries-with-the-most-overseas-military-bases-1237758/5/ "5 Countries With the Most Overseas Military Bases."] Insider Monkey, December 15, 2023.</ref><ref>[https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=amusB9j7Oz4 "Why 90% Of Foreign Military Bases Are American."] AJ+ on YouTube, Jan 13, 2022.</ref> many anti-base movements around the world have been directed at U.S. bases. | |||

Among the many grievances expressed by anti-base movement activists are issues such as criminal and negligent activity of base personnel, the environmental pollution and destruction generated by U.S. bases, the erosion of national sovereignty that occurs with the U.S. military presence in host locations, and the international provocations and tensions that occur when countries host US bases and collaborate with US military exercises (such as the biennial US-led [[Rim of the Pacific Exercise|RIMPAC]] exercises).<ref>[https://socialistchina.org/2022/07/27/the-feminist-response-to-rimpac-and-the-us-war-against-china/ “The Feminist Response to RIMPAC and the US War against China.”] Friends of Socialist China, July 27, 2022. [https://web.archive.org/web/20230922091207/https://socialistchina.org/2022/07/27/the-feminist-response-to-rimpac-and-the-us-war-against-china/ Archived] 2023-09-22.</ref> | |||

As of a 2021 estimate, the U.S. has approximately 750 bases around the world in at least 80 countries, with the largest concentration of them being in [[Japan]] (especially in [[Okinawa Prefecture|Okinawa]]), followed by [[Federal Republic of Germany|Germany]] and [[Republic of Korea|south Korea]],<ref>Mohammed Hussein and Mohammed Haddad. [https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/9/10/infographic-us-military-presence-around-the-world-interactive#:~:text=Upwards%20of%20750%20US%20bases,is%20published%20by%20the%20Pentagon. "Infographic: US military presence around the world."] Al Jazeera, 10 September 2021. [https://web.archive.org/web/20240328094244/https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/9/10/infographic-us-military-presence-around-the-world-interactive#:~:text=Upwards%20of%20750%20US%20bases,is%20published%20by%20the%20Pentagon. Archived] 2024-03-28.</ref> resulting in many corresponding anti-base movements. There are also anti-base movements within locations claimed by the U.S. as its own territory, some examples being [[Guam]] and [[Hawaii| | == Prevalence of US bases == | ||

As of a 2021 estimate, the U.S. has approximately 750 bases around the world in at least 80 countries, with the largest concentration of them being in [[Japan]] (especially in [[Okinawa Prefecture|Okinawa]]), followed by [[Federal Republic of Germany|Germany]] and [[Republic of Korea|south Korea]],<ref>Mohammed Hussein and Mohammed Haddad. [https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/9/10/infographic-us-military-presence-around-the-world-interactive#:~:text=Upwards%20of%20750%20US%20bases,is%20published%20by%20the%20Pentagon. "Infographic: US military presence around the world."] Al Jazeera, 10 September 2021. [https://web.archive.org/web/20240328094244/https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/9/10/infographic-us-military-presence-around-the-world-interactive#:~:text=Upwards%20of%20750%20US%20bases,is%20published%20by%20the%20Pentagon. Archived] 2024-03-28.</ref> resulting in many corresponding anti-base movements. There are also anti-base movements within locations claimed by the U.S. as its own territory, some examples being [[Guam]] and [[Hawaii|Hawaiʻi]] .<ref>Chris Gelardi and Sophia Perez. [https://www.thenation.com/article/archive/guam-colonialism/ “‘Biba Guåhan!’: How Guam’s Indigenous Activists Are Confronting Military Colonialism.”] The Nation, October 21, 2019.</ref><ref>Jedra, Christina. [https://www.civilbeat.org/2022/03/how-hawaii-activists-helped-force-the-militarys-hand-on-red-hill/ “How Hawaii Activists Helped Force the Military’s Hand on Red Hill.”] Honolulu Civil Beat, March 14, 2022. [https://web.archive.org/web/20240222203207/https://www.civilbeat.org/2022/03/how-hawaii-activists-helped-force-the-militarys-hand-on-red-hill/ Archived] 2022-02-22.</ref> | |||

Additionally, some anti-base movements oppose bases which are not formally considered to be a US base by law, but which effectively serve as a US base. An example of this would be the [[Military-Civilian Port Complex]] in south Korea, technically a south Korean base, but which local activists have explained is a place where "strategic assets in the US military can stop by whenever they please according to American interests."<ref>[https://english.hani.co.kr/arti/english_edition/e_international/820635.html “American Nuclear Submarine Enters Jeju Naval Base.”] Hankyoreh, 2017. [https://web.archive.org/web/20230325090226/https://english.hani.co.kr/arti/english_edition/e_international/820635.html Archived] 2023-03-25.</ref> | |||

== Issues with US bases == | |||

=== Violence toward local population === | |||

The violent crimes of U.S. military personnel and U.S. civilian contractors working in base areas include numerous killings and sexual assault crimes committed against the citizens of the countries where they are stationed.<ref>Mitchell, Jon. [https://theintercept.com/2021/10/03/okinawa-sexual-crimes-us-military/ “NCIS Case Files Reveal Undisclosed U.S. Military Sex Crimes in Okinawa.”] The Intercept. October 3, 2021. [https://web.archive.org/web/20220806191815/https://theintercept.com/2021/10/03/okinawa-sexual-crimes-us-military/ Archived] 2022-08-06.</ref> | |||

In addition to violence perpetrated by individual personnel against locals, negligence during routine activities of bases have also caused violent damage to local populations, such as people being seriously injured and killed by errant bombs.<ref>[https://en.yna.co.kr/view/AEN20120905010200315 "Bombing ends, but village still not free from past."] Yonhap News Agency. September 12, 2012. [https://web.archive.org/web/20220927084225/https://en.yna.co.kr/view/AEN20120905010200315 Archived] 2022-09-27. </ref> | |||

Areas with a base presence also face issues of increased [[sex trafficking]]. In south Korea, a legally-sanctioned prostitution industry was purposely encouraged and maintained by the government in special zones around US bases, with this system persisting for decades.<ref>Shorrock, Tim. [https://newrepublic.com/article/155707/united-states-military-prostitution-south-korea-monkey-house “Welcome to the Monkey House.”] The New Republic. December 2, 2019. [https://web.archive.org/web/20220926021611/https://newrepublic.com/article/155707/united-states-military-prostitution-south-korea-monkey-house Archived] 2022-09-26.</ref> | |||

=== Environmental destruction === | |||

[[File:Okinawa pollution.png|alt=Outdoor photo showing a major leak of PFAS foam, with a parked car partially submerged in the foam almost up to its windows.|thumb|Toxic PFAS foam leak at Kadena Air Base in Okinawa.]]The environmental destruction brought about by base presence takes a range of forms, arising from the initial construction of the base and how it alters the environment, to the ongoing activities of the base in that particular location, to the after-effects that remain even after a base has ceased operation. Some examples of environmental hazards are leakages of jet fuel into local drinking water, toxic PFAS foam leaks, litter from practice drills bleeding chemicals into the ground and water, and extreme noise pollution. In addition to physically hazardous pollution, culturally or spiritually significant sites can be destroyed or desecrated by base presence. | |||

A 2018 petition by [[World Can't Wait]] to stop RIMPAC exercises, addressed to the then-governor of Hawaiʻi, describes further examples:<blockquote>Retired military ships are towed out to sea and then targeted with missiles and torpedoes until they sink to a watery graveyard on the ocean floor. There they leach toxic chemicals, including PCBs, which accumulate in the bodies of fish, dolphins and whales – and ultimately into our food. Amphibious landing exercises, which include heavy tracked vehicles, damage reefs, erode shoreline, and endanger wildlife. [...] Areas that have been used for live fire training and bombing practice are uninhabitable; bombing and live fire practice is not only continuing but escalating in the age of the “Pacific Pivot”. Indigenous Hawaiian cultural sites have been destroyed. U.S. Military fuel storage tanks are leaking poisons into the drinking water in Hawai`i's most populous city. Vast areas of land and water are so toxic as to be unusable.<ref>[https://www.change.org/p/for-people-land-air-sea-stop-rimpac-military-exercises "For People, Land, Air and Sea: Stop RIMPAC Military Exercises."] Petition to Governor of Hawaii David Ige, started by World Can't Wait-Hawai`i. Change.org, May 17, 2018. [https://web.archive.org/web/20240403113410/https://www.change.org/p/for-people-land-air-sea-stop-rimpac-military-exercises Archived] 2024-04-03.</ref> </blockquote> | |||

=== National sovereignty === | |||

== Anti-base movements by location == | |||

== References == | == References == | ||

<references /> | <references /> | ||

Revision as of 11:43, 3 April 2024

Anti-base movement is a term[1] which refers to various movements which focus on opposing aspects of military bases, which can range from opposition to specific activities of bases or base personnel, to opposing their presence or construction in particular locations, to opposing their existence in general. It can also refer to these movements collectively.[2] Given that the majority of foreign military bases around the world are United States bases,[3][4][5] many anti-base movements around the world have been directed at U.S. bases. Among the many grievances expressed by anti-base movement activists are issues such as criminal and negligent activity of base personnel, the environmental pollution and destruction generated by U.S. bases, the erosion of national sovereignty that occurs with the U.S. military presence in host locations, and the international provocations and tensions that occur when countries host US bases and collaborate with US military exercises (such as the biennial US-led RIMPAC exercises).[6]

Prevalence of US bases

As of a 2021 estimate, the U.S. has approximately 750 bases around the world in at least 80 countries, with the largest concentration of them being in Japan (especially in Okinawa), followed by Germany and south Korea,[7] resulting in many corresponding anti-base movements. There are also anti-base movements within locations claimed by the U.S. as its own territory, some examples being Guam and Hawaiʻi .[8][9]

Additionally, some anti-base movements oppose bases which are not formally considered to be a US base by law, but which effectively serve as a US base. An example of this would be the Military-Civilian Port Complex in south Korea, technically a south Korean base, but which local activists have explained is a place where "strategic assets in the US military can stop by whenever they please according to American interests."[10]

Issues with US bases

Violence toward local population

The violent crimes of U.S. military personnel and U.S. civilian contractors working in base areas include numerous killings and sexual assault crimes committed against the citizens of the countries where they are stationed.[11]

In addition to violence perpetrated by individual personnel against locals, negligence during routine activities of bases have also caused violent damage to local populations, such as people being seriously injured and killed by errant bombs.[12]

Areas with a base presence also face issues of increased sex trafficking. In south Korea, a legally-sanctioned prostitution industry was purposely encouraged and maintained by the government in special zones around US bases, with this system persisting for decades.[13]

Environmental destruction

The environmental destruction brought about by base presence takes a range of forms, arising from the initial construction of the base and how it alters the environment, to the ongoing activities of the base in that particular location, to the after-effects that remain even after a base has ceased operation. Some examples of environmental hazards are leakages of jet fuel into local drinking water, toxic PFAS foam leaks, litter from practice drills bleeding chemicals into the ground and water, and extreme noise pollution. In addition to physically hazardous pollution, culturally or spiritually significant sites can be destroyed or desecrated by base presence. A 2018 petition by World Can't Wait to stop RIMPAC exercises, addressed to the then-governor of Hawaiʻi, describes further examples:

Retired military ships are towed out to sea and then targeted with missiles and torpedoes until they sink to a watery graveyard on the ocean floor. There they leach toxic chemicals, including PCBs, which accumulate in the bodies of fish, dolphins and whales – and ultimately into our food. Amphibious landing exercises, which include heavy tracked vehicles, damage reefs, erode shoreline, and endanger wildlife. [...] Areas that have been used for live fire training and bombing practice are uninhabitable; bombing and live fire practice is not only continuing but escalating in the age of the “Pacific Pivot”. Indigenous Hawaiian cultural sites have been destroyed. U.S. Military fuel storage tanks are leaking poisons into the drinking water in Hawai`i's most populous city. Vast areas of land and water are so toxic as to be unusable.[14]

National sovereignty

Anti-base movements by location

References

- ↑ “I use the term “antibase movement” because it is widely used by movement members and scholars and because such movements, strictly speaking, are “anti-” in the sense that they are opposed to some aspect of the life of a base or its personnel.”

David Vine (2019). No Bases? Assessing the Impact of Social Movements Challenging US Foreign Military Bases, vol. Volume 60, Number S19. [PDF] Current Anthropology. - ↑ Yeo, Andrew. "Not in Anyone's Backyard: The Emergence and Identity of a Transnational Anti-Base Network." International Studies Quarterly, Vol. 53, No. 3 (Sep., 2009), pp. 571-594. Oxford University Press.

- ↑ David Vine, Patterson Deppen and Leah Bolger. "Drawdown: Improving U.S. and Global Security Through Military Base Closures Abroad." Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft, September 20, 2021. Archived 2024-03-12.

- ↑ Jawad, Ashar. "5 Countries With the Most Overseas Military Bases." Insider Monkey, December 15, 2023.

- ↑ "Why 90% Of Foreign Military Bases Are American." AJ+ on YouTube, Jan 13, 2022.

- ↑ “The Feminist Response to RIMPAC and the US War against China.” Friends of Socialist China, July 27, 2022. Archived 2023-09-22.

- ↑ Mohammed Hussein and Mohammed Haddad. "Infographic: US military presence around the world." Al Jazeera, 10 September 2021. Archived 2024-03-28.

- ↑ Chris Gelardi and Sophia Perez. “‘Biba Guåhan!’: How Guam’s Indigenous Activists Are Confronting Military Colonialism.” The Nation, October 21, 2019.

- ↑ Jedra, Christina. “How Hawaii Activists Helped Force the Military’s Hand on Red Hill.” Honolulu Civil Beat, March 14, 2022. Archived 2022-02-22.

- ↑ “American Nuclear Submarine Enters Jeju Naval Base.” Hankyoreh, 2017. Archived 2023-03-25.

- ↑ Mitchell, Jon. “NCIS Case Files Reveal Undisclosed U.S. Military Sex Crimes in Okinawa.” The Intercept. October 3, 2021. Archived 2022-08-06.

- ↑ "Bombing ends, but village still not free from past." Yonhap News Agency. September 12, 2012. Archived 2022-09-27.

- ↑ Shorrock, Tim. “Welcome to the Monkey House.” The New Republic. December 2, 2019. Archived 2022-09-26.

- ↑ "For People, Land, Air and Sea: Stop RIMPAC Military Exercises." Petition to Governor of Hawaii David Ige, started by World Can't Wait-Hawai`i. Change.org, May 17, 2018. Archived 2024-04-03.