(→Algeria, Tunisia and the FLN (1953-1961): minor changes and a picture that looks cool) Tag: Visual edit |

Tag: Visual edit |

||

| Line 48: | Line 48: | ||

=== Algeria, Tunisia and the FLN (1953-1961) === | === Algeria, Tunisia and the FLN (1953-1961) === | ||

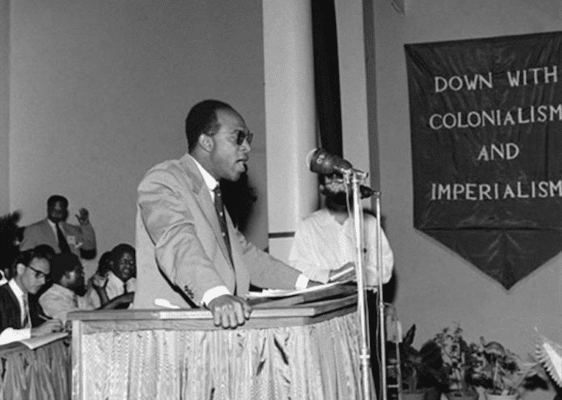

[[File:FanonConference.png|thumb| | [[File:FanonConference.png|thumb|450x450px|Frantz Fanon speaking at the [[All African People’s Conference (AAPC)]], which was held in Accra, Ghana, between 5 and 13 December 1958.<ref name=":6">{{Web citation|author=Hamza Hamouchene|newspaper=Review of African Political Economy (ROAPE)|title=Frantz Fanon and the Algerian revolution today|date=2021-04-06|url=https://roape.net/2021/05/06/frantz-fanon-and-the-algerian-revolution-today/|retrieved=2023-07-21}}</ref>]] | ||

He accepted a position as ''chef de service'' (chief of staff) for the psychiatric ward of the Blida-Joinville hospital in Algeria. | He accepted a position as ''chef de service'' (chief of staff) for the psychiatric ward of the Blida-Joinville hospital in Algeria. The 1954 proclamation the political party of independence, the [[Front de Libération Nationale (FLN)|''Front de Libération Nationale'' (FLN)]] for armed struggle against the occupation marked the beginnings of the final stage of the resistance that would eventually lead to national independence in 1962.<ref>{{Citation|author=Ziad Bentahar|year=2009|title=Frantz Fanon: Travelling Psychoanalysis and Colonial Algeria|chapter-url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/44030671|page=133|publisher=Mosaic: An Interdisciplinary Critical Journal, Vol. 42, No. 3, 127-140|doi=10.2307/44030671}}</ref> Working in a French hospital, Fanon was increasingly responsible for treating both the psychological distress of the soldiers and officers of the French army who carried out torture in order to suppress anti-colonial resistance and the trauma suffered by the Algerian torture victims.<ref name=":6" /> | ||

=== Death (1961) === | === Death (1961) === | ||

Revision as of 16:47, 21 July 2023

Frantz Fanon | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | July 20, 1925 Fort-de-France, Martinique, French West Indies |

| Died | December 6, 1961 (aged 36) Bethesda, Maryland, USA |

| Cause of death | Leukemia |

| Known for | Black Skin, White Masks, The Wretched of the Earth |

Frantz Fanon (July 20, 1925 – December 6, 1961) was a psychiatrist, anti-colonial political theorist, author, and revolutionary from the Caribbean island of Martinique. He is the author of various works including Black Skin, White Masks (1952) and The Wretched of the Earth (1961). Born as a colonial French subject, he eventually travelled to France for his education in psychiatry. In the latter portion of his life, he was involved with the Algerian National Liberation Front (French: Front de Libération Nationale; FLN) in the Algerian independence struggle against the French.[1] He also worked in Tunisia with Algerian independence forces, and served as the Ambassador to Ghana for the Provisional Algerian Government. He passed away in 1961, after being diagnosed with leukemia.[2]

Fanon's political thought deals heavily with the implications and consequences of colonization, focusing considerably on anti-colonial struggles of his time as well as on the effects of colonization on the human psyche.

In 1953, Fanon was named the Head of the Psychiatry Department of the Blida-Joinville Hospital in Algeria. There, via his patients, Fanon gained increased insight into the torture and brutality ongoing under French rule. In 1956, Fanon resigned from his position with the French government to struggle for Algerian independence.[2][3] He documented French atrocities for the French and Algerian media.[4] According to Fanon, the only way for anti-colonial governments to prevent military coups is to politically educate the army and create civilian militias.[5]

Early Life and Education

Early life (1925-1943)

One of eight children, Frantz Fanon was born on the 20 July 1925 in Fort-de-France, the capital of Martinique (then a French colony and later a département). His father, Casimir Fanon was a minor customs official, his mother Elanore Fanon kept a shop. Most of the Fanon family was educated; five of the children went to France for higher education. By the standards of the white creoles or békés (descendants from the original plantation-owners and white businessmen), the family was not wealthy, but the Fanon’s were prosperous enough to employ domestic help and to pay for piano lessons for Frantz’s sisters.[6] Fanon attended Lycée Victor Schoelcher in Fort-de-France and gained a reputation as an avid reader and keen footballer. Joby, two years older, shared Frantz’s bed, friends and passion for football. But Joby and Frantz were also members of a gang; again Frantz was the dominant figure, organising petty misdemeanours and scuffles with rivals[7], something attested to by Fanons relatives.[6] As Fanon grew into adolescence, his interest in football waned. He spent hours every week in the public library, reading French literature and philosophy. Pupils were taught that they were French and European[7].

The war declared in 1939 led to panic in Martinique: schools closed and trenches were dug, precautions for air raids that did not come. Frantz and Joby were sent to their uncle Edouard Fanon, a teacher, in the countryside. After two years, the school was reopened. This school was at the time the most prestigious high school in Martinique, where Fanon came to admire one of the school's teachers, poet and writer Aimé Césaire. They met in 1940, where he was known for his epic poem Cahier d’un retour au pays natal.[7]

Fanon’s great-grandfather was the son of a slave. He owned land on the Atlantic coast and grew cocoa. Fanon’s mother, Éléonore, was born to unmarried parents. Her father’s white predecessors were said to have come from Strasburg, Austria; the name ‘Frantz’ was said to reflect this distant European ancestry.[7]His parents encouraged him to speak French instead of creole, the language of the “lower” classes, in his interaction with the larger society[8], as was common practice in Antillian society at the time, being percieved as a simplified "Negro-french".[7] Fanon writes:

"The middle class in the Antilles never speak Creole except to their servants. In school the children of Martinique are taught to scom the dialect. One avoids Creolisms. Some families completely forbid the use of Creole, and mothers ridicule their children for speaking it."[9]

Martinique at the time had a population of 43,000 (1925). Sugar production had gradually become less profitable. Agricultural wage-labourers attempted to find work in the docks and coal depot, as there was a agricultural crisis. The town centre became home to shopkeepers, lawyers and doctors. Easily eradicable diseases where prevalent, including elephantiasis, tuberculosis and leprosy; only in the 1950s was malaria eradicated.[7] Fanon describes Martinique's "racial structure" as follows:

"In Martinique it is rare to find hardened racial positions. The racial problem is covered over by economic discrimination and, in a given social class, it is above all productive of anecdotes. Relations are not modified by epidermal accentuations . . . In Martinique, when it is remarked that this or that person is in fact very black, this is said without contempt, without hatred. One must be accustomed to what is called the spirit of Martinique in order to grasp the meaning of what is said."[8]

He also writes in Black Skins White Masks:

At the age of twenty-at the time, that is, when the collective unconscious has been more or less lost, or is resistant at least to being raised to the conscious level-the Antillean recognizes that he is living an error. Why is that? Quite simply because-and this is very important-the Antillean has recognized himself as a Negro, but, by virtue of an ethical transit, he also feels {collective unconscious) that one is a Negro to the degree to which one is wicked, sloppy, malicious, instinctual. Everything that is the opposite of these Negro modes of behavior is white. This must be recognized as the source of Negrophobia in the Antillean. In the collective unconscious, black =ugliness, sin, darkness, immorality. In other words, he is Negro who is immoral. If I order my life like that of a moral man, I simply am not a Negro. Whence the Martinican custom of saying of a worthless white man that he has "a nigger soul. Color is nothing, I do not even notice it, I know only one thing, which is the purity of my conscience and the whiteness of my soul. "Me white like snow," the other said."[10]

World War II and Martinique (1943-1945)

After the fall of France in 1940, power in Martinique was concentrated in the hands of Admiral Robert, Commander of the West Atlantic Fleet and High Commissioner for the West Indian colonies since August 1939. Although the mayors of Martinique were ready to rally to De Gaulle’s call for resistance, Robert’s sympathies were with the collaborationist Vichy Government. The island was therefore blockaded by the Allies until 1943. Food shortages, inflation and a housing crisis were the result of the presence of the thousands of troops and sailors now on the island. The french navy was widely percieved as a racist occupation force, and their expeditions to requisition food led to open conflict between french soldiers and the people from Martinique. The békés supported Robert, wheras many Antillians supported de Gaulle. Some Antillians (labelled "dissidents") therefore attempted to voyage to Dominica, a English colony, to join the "Free French Forces". Among them was Fanon, who on his third attempt managed to reach Dominica, but could not enlist as Robert was overthrown in 1943 and replaced by a pro-Gaulle government. Fanon thereupon returned to Fort-de-France, and enlisted in the Fifth Infantry Batallion, which consisted of 1,200 black volunteers. In late 1943, Fanon sailed for basic military training in North Africa (including Algeria).

Fanon was part of the invasion force that landed near Toulon in August 1944 and then pushed north along the Napoleonic Road through the Alps and into Alsace. In November 1944 he was wounded while reloading a mortar, mentioned in dispatches and decorated with the Croix de Guerre for his bravery under fire.[6]

Fanon noted that it seemed to be black troops who were sent into combat first. The Martiniquans maintained their peculiar rank, neither natives nor complete Frenchmen, but as they progressed north the army made the decision to ‘whiten’ the division. Fanon entered the war with a sense of France’s imperfection but also illusions of justice in an empire and nation indivisible. He would return with these ideas in tatters[7]:

"If I don’t come back, and if one day you should hear that I died facing the enemy, console each other, but never say: he died for the good cause. [. . .] This false ideology that shields the secularists and the idiot politicians must not delude us any longer. I was wrong!"[7]

He further elaborates in Black Skin, White Masks:

"When I was in military service I had the opportunity to observe the behavior of white women from three or four European countries when they were among Negroes at dances. Most of the time the women made involuntary gestures of flight, of withdrawing. their faces filled with a fear that was not feigned. And yet the Negroes who asked them to dance would have been utterly unable to commit any act at all against them, even if they had wished to do so"[11]

Martinique and France (1945-1953)

After returning to Martinique in the fall of 1945, where he focused on completing his secondary education, Fanon studied under Césaire and became very close to him both intellectually and politically. In addition to absorbing his literary work and poetry, Fanon took part in Césaire’s successful campaign to be elected to the French parliament as a member of the Communist Party. Fanon did not, however, share Césaire’s enthusiasm for France’s decision (in 1946) to transform Martinique from a colony to a département (Département d’outre-mer) of France. He also thought that the urbane Césaire did not have a good understanding of rural Martinicans.[8]

Fanon wanted to continue his education, and looked abroad as Martinique did not have a University. The legislation adopted in August 1945 provided him with the possibility; student grants were now available for war veterans, and Fanon left for France to become a dentisty in Paris.[6] He quickly changed to Medicine and enrolled in the Faculty of Medicine in Lyon in 1947.[8] In his fifth year, he opted to study psychiatry rather than general medicine. He attended philosophy lectures by Merleau-Ponty, read Sartre, wrote three plays in 1949 - of which only two survive: The Drowning Eye (L’Oeil se noie), and Parallel Hands (Les Mains parallèles) whereas the third remains lost (La Conspiration)[12] - gave talks on surrealism and poetry to student societies, and edited a little magazine entitled Tam-tam, but no copies of that short-lived publication have survived. Despite his many extra-curricular activities, Fanon successfully completed his degree in 1951.[6]

He also enrolled in the Philosophy Department at the School of Liberal Arts. He attended courses taught by Merleau-Ponty and by Andre Leroi-Gourhan. His interests ran to ethnology, phenomenology, and Marxism, but existentialism and psychoanalysis took top billing. Fanon was an avid reader with wide-ranging reading habits: Levi-Strauss, Mauss, Heidegger, Hegel, as well as Lenin and the young Marx. In Paris he formed relationships with people who had deep political commitments and who helped pique his interest in Marxist methodology, but he never developed a need for clearcut political affiliations. He was especially drawn to psychoanalytical works and to Sartre. He read Freud as well as the handful of works by Jacques Lacan that were available at the time.[13]

In 1948 Fanon started a relationship with Michelle, a medical student, who soon became pregnant. He left her for an 18-year-old high school student, Josie, whom he married in 1952. Fanon never learned to type and one of the couple’s first collaborations involved Josie typing the first drafts of Black Skin, White Masks. For the rest of Fanon’s life, Josie was his companion and collaborator; after his death she remained in Algeria until her suicide in 1989. In February 1947, Fanon heard that his father had died.[14]

He was reputedly close to the local PCF branch, though never a member, but participated in its anti-colonial demonstrations. [14]Fanon had, since his university years, already been involved in the anti-colonial struggle; he belonged to the inner circle at Presence africaine, and he had been a close and attentive reader of the many issues Temps modernes had devoted to the colonial situation.[13]

Frantz Fanon published Black Skins, White Masks in 1952. Originally conceived in 1951 as a medical dissertation, entitled "Essay on the Disalienation of the Black"[13], it was swiftly rejected by his professors as defying all known thesis protocols[14]. Fanon therefore submitted a classical thesis on Friedrich’s disease, entitled "Altérations mentales, modifications caractérielles, troubles psychiques et déficit intellelectuel dans Thérédo-dégénération spino-cérébelleuse: à propos d'un cas de maladie de Fried avec délire de possession"[6], and published Black Skins, White Masks as a book. After receiving Fanon's manuscript at Seuil, Francis Jeanson (leader of the pro-Algerian independence Jeanson network) invited him to an editorial meeting. Amid Jeanson's praise of the book, Fanon exclaimed: "Not bad for a nigger, is it?" Insulted, Jeanson dismissed Fanon from his office. Later, Jeanson learned that his response had earned him the writer's lifelong respect, and Fanon acceded to Jeanson's suggestion that the book be entitled Black Skin, White Masks.[13] He also published a related article entitled The "North African Syndrome" in 1952.[15]

Peau noire, masques blancs and the related article on the ’North-African Syndrome’ (in which he details his account of systemic clinical racism) are also products of Fanon’s hostile encounter with the work of the so-called Algiers school of psychiatry and of his early clinical experience of working with the immigrants (mainly Algerian) attracted to Lyon by the chemical and textile industries. This is described by Macey as follows:

"The work of Antoine Porot and the Algiers school is an expression of France’s attempts to understand her colonial subjects and the apparently mysterious symptoms they presented by constructing a cross-cultural psychiatry. It draws upon a variety of discourses, ranging from climatic theories of epidemiology to theories of psycho-social evolution that present the white race as the incarnation of a higher civilization, and to Levy-Bruhl’s theses on the existence of a primitive mentality. It is also heavily influenced by a traditional hostility to Islam, viewed as a pathogenic agent rather than as one of the great monotheistic religions. Lack of intellectual curiosity, suggestibility and a reliance on magical modes of thought are held to be characteristically North-African features. Islam is said to induce fatalism and chronic laziness, whilst wild mood swings between sullen indifference and manic euphoria lead to explosions of criminal impulsiveness and, in the sexual domain, outbursts of homicidal jealousy. The work of the Algiers school was enormously influential and enjoyed a surprising longevity. Manuals of clinical psychiatry continued to include articles on the psychopathology of North Africans until the 1970s. They contained no articles on the psychopathology of the white Europeans who presumably represented both a norm and a higher stage of evolution. "[6]

Frantz Fanon started a internship in the Saint Alban psychiatric hospital in the Lozère region in 1952 while he was preparing for the Medicat des hopitaux psychiatriques.[6] Most psychiatric hospitals were still the carceral institutions provided for by the law of 1838, but there were no walls at Saint-Alban. Fanon completed his internship at the Saint-Alban psychiatric hospital in France, where he studied the emergent "institutional psychotherapy" then being pioneered by the psychiatrist François Tosquelles at the institute. Institutional psychotherapy sought the reintegration of the patient into society through the creation of a model community within the hospital's walls, placing emotional support of the patient above the needs of social discipline. This experience was formative for Fanon.[16]

Fanon’s completion of his medical studies was followed by a further period of uncertainty. A post was available in Martinique, but Fanon’s application was unsuccessful. After taking a temporary post in Pontorson on the Normandy coast, Fanon was appointed to a consultancy in Blida, Algeria from 1953.[6]

Political Life and Death

Algeria, Tunisia and the FLN (1953-1961)

He accepted a position as chef de service (chief of staff) for the psychiatric ward of the Blida-Joinville hospital in Algeria. The 1954 proclamation the political party of independence, the Front de Libération Nationale (FLN) for armed struggle against the occupation marked the beginnings of the final stage of the resistance that would eventually lead to national independence in 1962.[18] Working in a French hospital, Fanon was increasingly responsible for treating both the psychological distress of the soldiers and officers of the French army who carried out torture in order to suppress anti-colonial resistance and the trauma suffered by the Algerian torture victims.[17]

Death (1961)

Work and Thought

Black Skin, White Mask

A Dying Colonialism

The Wretched of the Earth

Toward the African Revolution

Fanons Psychiatry

Other Works and Interpretation

Legacy

Bibliography

- Black Skin, White Masks (1952)

- A Dying Colonialism (1959)

- The Wretched of the Earth (1961)

- Toward the African Revolution (1964)

- Alienation and Freedom (2018)

References

- ↑ “Remembering Algerian Revolutionary Frantz Fanon.” teleSUR, Dec. 6, 2017. Archived 2022-08-18.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 “Martinique and Algeria’s Franz Fanon Remembered.” teleSUR. 2016. Archived 2023-03-19.

- ↑ Drabinski, John. "Frantz Fanon." Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Stanford.edu. Mar 14, 2019. Archived 2023-03-19.

- ↑ Vijay Prashad (2008). The Darker Nations: A People's History of the Third World: 'Algiers' (p. 121). [PDF] The New Press. ISBN 9781595583420 [LG]

- ↑ Vijay Prashad (2008). The Darker Nations: A People's History of the Third World: 'La Paz' (p. 139). [PDF] The New Press. ISBN 9781595583420 [LG]

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 6.7 6.8 David Macey (1996). Frantz Fanon 1925-1961. History of Psychiatry, 7 (28), 489-497. doi: 10.1177/0957154x9600702802 [HUB]

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 Leo Zeilig (2021). Frantz Fanon: A Political Biography (pp. 15-27). I.B.Tauris. [LG]

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Peter Hudis (2015). Frantz Fanon: Philosopher of the Barricades: 'The Path to Political and Philosophical Commitment' (pp. 14-19). London: Pluto Press. [LG]

- ↑ Frantz Fanon (1986 (1952)). Black Skins, White Masks (p. 20). [PDF] London: Pluto Press, translated by Charles Lam Markmann.

- ↑ Frantz Fanon (1986 (1952)). Black Skin, White Masks (pp. 192-193). [PDF] London: Pluto Press, translated by Charles Lam Markmann.

- ↑ Frantz Fanon (1986 (1952)). Black Skins, White Masks (p. 156). [PDF] London: Pluto Press, translated by Charrles Lam Markmann.

- ↑ Frantz Fanon (2018). Alienation and Freedom: 'Fanon, revolutionary playwright (Robert J.C. Young)' (p. 11). London: Bloomsbury Academic. [LG]

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 Alice Cherki (2006). Frantz Fanon: A portrait (pp. 16-24). Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [LG]

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Leo Zeilig (2021). Frantz Fanon: A Political Biography (pp. 31-36). I.B. Tauris. [LG]

- ↑ Frantz Fanon (1959). Towards the African Revolution: Political Essays: 'The "North African Syndrome" (1952)' (p. 3). [PDF] New York: Grove Press. [LG]

- ↑ Richard C. Keller (2007). Clinician and Revolutionary: Frantz Fanon, Biography, and the History of Colonial Medicine (p. 827). Bulletin of the History of Medicine, Vol. 81, No. 4, 823-841. doi: 10.2307/44452161 [HUB]

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Hamza Hamouchene (2021-04-06). "Frantz Fanon and the Algerian revolution today" Review of African Political Economy (ROAPE). Retrieved 2023-07-21.

- ↑ Ziad Bentahar (2009). Frantz Fanon: Travelling Psychoanalysis and Colonial Algeria (p. 133). Mosaic: An Interdisciplinary Critical Journal, Vol. 42, No. 3, 127-140. doi: 10.2307/44030671 [HUB]