Library:The Motorcycle Diaries: Difference between revisions

Connolly1916 (talk | contribs) (Changed date) Tag: Visual edit |

Connolly1916 (talk | contribs) (Added intro and first 2 chapters) Tag: Visual edit |

||

| Line 227: | Line 227: | ||

=== 1997 === | === 1997 === | ||

Che’s remains are finally located in Bolivia and returned to Cuba, where they are placed in a memorial at Santa Clara. | Che’s remains are finally located in Bolivia and returned to Cuba, where they are placed in a memorial at Santa Clara. | ||

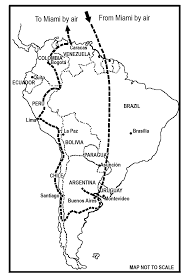

== Map and Itinerary == | |||

=== Map of the Motorcycle Diaries === | |||

[[File:Che Guevara Motorcycle Map.png|center|thumb]] | |||

=== Itinerary of the Motorcycle Diaries === | |||

ARGENTINA | |||

1951 | |||

December Córdoba to Buenos Aires | |||

1952 | |||

January 4 Leave Buenos Aires | |||

January 6 Villa Gesell | |||

January 13 Miramar | |||

January 14 Necochea | |||

January 16–21 Bahía Blanca | |||

January 22 En route to Choele Choel | |||

January 25 Choele Choel | |||

January 29 Piedra del Águila | |||

January 31 San Martín de los Andes | |||

February 8 Nahuel Huapí | |||

February 11 San Carlos de Bariloche | |||

CHILE | |||

February 14 Take the Modesta Victoria to Peulla | |||

February 18 Temuco | |||

February 21 Lautaro | |||

February 27 Los Ángeles | |||

March 1 Santiago de Chile | |||

March 7 Valparaíso | |||

March 8–10 Aboard the San Antonio | |||

March 11 Antofagasta | |||

March 12 Baquedano | |||

March 13–15 Chuquicamata | |||

March 20 Iquique (and the Toco, La Rica Aventura and Prosperidad Nitrate Companies) | |||

March 22 Arica | |||

PERU | |||

March 24 Tacna | |||

March 25 Tarata | |||

March 26 Puno | |||

March 27 Sail on Lake Titicaca | |||

March 28 Juliaca | |||

March 30 Sicuani | |||

March 31 – April 3 Cuzco | |||

April 4–5 Machu Picchu | |||

April 6–7 Cuzco | |||

April 11 Abancay | |||

April 13 Huancarama | |||

April 14 Huambo | |||

April 15 Huancarama | |||

April 16–19 Andahuaylas | |||

April 22–24 Ayacucho to Huancallo | |||

April 25–26 La Merced | |||

April 27 Between Oxapampa and San Ramón | |||

April 28 San Ramón | |||

April 30 Tarma | |||

May 1–17 Lima | |||

May 19 Cerro de Pasco | |||

May 24 Pucallpa | |||

May 25–31 Aboard La Cenepa sailing down Río Ucayali, a tributary of the Amazon | |||

June 1–5 Iquitos | |||

June 6–7 Aboard El Cisne sailing to the leper colony of San Pablo | |||

June 8–20 San Pablo | |||

June 21 Aboard the Mambo-Tango raft on the Amazon | |||

COLOMBIA | |||

June 23 – July 1 Leticia | |||

July 2 Leave Leticia by plane | |||

July 2–10 Bogotá | |||

July 12–13 Cúcuta | |||

VENEZUELA | |||

July 14 San Cristóbal | |||

July 16 Between Barquisimeto and Corona | |||

July 17–26 Caracas, where Che and Alberto separate | |||

UNITED STATES | |||

Late July Miami | |||

ARGENTINA | |||

August Che returns to his family in Córdoba | |||

== Introduction by Cintio Vitier == | |||

If there is one hero in Latin America’s struggle for liberation — stretching from Bolívar’s* time until our own —who has attracted young people from Latin America and from all over the world, that hero is Ernesto Che Guevara. And though since his death he has become a modern myth, he has not yet been stripped of his youthful vitality. To the contrary, his mythic status has only served to heighten his youthfulness which, together with his daring and his purity, seem to constitute the secret essence of his charisma. | |||

Becoming a myth, a symbol of so many scattered and fiercely held hopes, presupposes that such a character possesses a kind of gravity, a certain solemnity. It is good that this is so; historic utopia needs faces to embody it. But we shouldn’t lose sight of the everyday nature of those human beings, who were children, teenagers and young people before they acquired the skills by which to guide us. It is not that I want to bury their exceptional natures in the common or familiar aspects of their lives, but that knowledge of those first, formative stages shows us the starting point for their later trajectories | |||

This is especially true in Che’s case, whose account of this first trip he made with his friend Alberto Granado offers the young at heart such a close and cheerful, serious and at the same time ironic image of the young man, that we can almost glimpse his smile and hear his voice and asthmatic wheeze. He is young, like them, and he filled his whole life with youthfulness and matured his youth without diluting it. | |||

This edition of The Motorcycle Diaries, the notes describing a journey made without hesitation, aboard the noisy motorcycle La Poderosa II (which gave out halfway, but only after transmitting to the adventure a joyous impulse we, too, receive), free as the wind, with the sole purpose of getting to know the world, is dedicated to people whose youth is not merely sequential, but wholehearted and spiritual. | |||

In the first pages, the young man who would become one of the genuine heroes of the 20th century cautions us, “This is not a story of heroic feats.” The word “heroic” rings out above the others, because we cannot read these pages without thinking of Che’s future, an image of him in the Sierra Maestra, an image which reached perfection at Quebrada del Yuro in Bolivia.† | |||

If this youthful adventure had not been prelude to his revolutionary formation, these pages would be different, and we would read them differently, though we cannot imagine how. Simply knowing that they are Che’s — though he wrote them before becoming Che — makes us believe that he had a presentiment regarding the way they should be read. For example:<blockquote>The person who wrote these notes passed away the moment his feet touched Argentine soil again. The person who reorganizes and polishes them, me, is no longer, at least I’m not the person I once was. All this wandering around “Our America with a capital A” has changed me more than I thought.</blockquote>These pages are a testimony — a photographic negative, as he also put it — of an experience that changed him, a first “departure” toward the outer world which, like his final departure, was Quixotic in its semi-unconscious style and, as for Quixote, had the same effect on the scope of his consciousness. This was the “spirit of a dreamer” experiencing an awakening. | |||

In principle, and with the perfect logic of the unforeseeable, their journey was at first directed toward North America, as in fact it turned out to be: toward the “photographic negative” of North America that is South American poverty and helplessness, and toward real knowledge of what North America means for us. | |||

“The enormity of our endeavor escaped us in those moments; all we could see was the dust on the road ahead and ourselves on the bike, devouring kilometers in our flight northward.” Wasn’t that “dust on the road,” though without Che realizing it, really the same dust José Martí‡ saw when he traveled from La Guaira to Caracas “in a common little coach”? Wasn’t it the Quixotic dust in which the ghosts of American redemption appeared, “the natural cloud of dust that must rise when our terrible casing of chains falls to the ground”?§ But Martí was coming from the north, and Che was traveling toward himself, catching only glimpses of his destiny, which we glimpse as well through his anecdotes and vignettes. | |||

Comeback, the little dog with “aviator’s impulses” Che presents to us so comically, leaping around the motorcycle from Villa Gesell to Miramar, reappears years later in the Sierra Maestra mountains as a puppy who must be strangled, because of its “hysterical howls” during an unsuccessful ambush laid in the hope of catching [Batista’s notorious army colonel] Sánchez Mosquera. “With one last nervous twitch, the puppy stopped moving. There it lay, sprawled out, its little head spread over the twigs.”** But, at the end of this incident from Episodes of the Revolutionary War, another dog appears lying in the hamlet of Mar Verde:<blockquote>Félix patted its head, and the dog looked at him. Félix returned the glance, and then he and I exchanged a guilty look. Suddenly everyone fell silent. An imperceptible stirring came over us, as the dog’s meek yet roguish gaze seemed to contain a hint of reproach. There, in our presence, though observing us through the eyes of another dog, was the murdered puppy</blockquote>It was Comeback who had returned, living up to his name, reminding us also of what Ezequiel Martínez Estrada, our other great Argentine, said about José Martí’s campaign diary:<blockquote>These emotions, these sensations, cannot be described or expressed in the language of poets and painters, musicians and mystics; they must be… absorbed without reply, as animals do with their contemplative and entranced eyes.††</blockquote>A comparison of Episodes with The Motorcycle Diaries shows us that, even though more than 10 years had passed, the latter was a literary model for the former. It contains the same moderation; the same candor; the same nimble freshness; exactly the same concept of moments used to provide unity for each brief chapter; and, of course, the same imperturbable steadiness that accepts both happy and tragic events without sharp inhalation or exhalation. | |||

It isn’t literary skill but fidelity to experience and narrative effectiveness that is sought. When both are attained, skill follows naturally, taking its allotted place, neither blinding nor disturbing but making its contribution. Here, with little fumbling or hesitation, Che’s style is already formed. The years would polish it, just as he himself polished his will with the pleasure of an artist, though not that of a wordsmith: a quiet shyness forced him not to dwell too much but to push on with the words toward the poetry of the naked image, which his minimal touch turned into reality. His “I—it-inme” circle opens and closes continually without ever becoming dense, accommodating a style that prefers to remain hidden. The prose on the page sheds light, though does not drag on the imperceptible lightness of the narrative. It flows between description of feeling (in Episodes, “the determined murderer left a trail of burned huts, of sullen sadness…”) and narrative accounts in which he searches for himself (in the Diaries, “Man, the measure of all things, speaks here through my mouth and narrates in my own language that which my eyes have seen”) and sometimes even seems to be watching us. | |||

Che’s colorful prose paints objects as far as his eyes can see and often, if the landscape permits it, with an intimate touch:<blockquote>The road snakes between the low foothills that sound the beginning of the great cordillera of the Andes, then descends steeply until it reaches an unattractive, miserable town, surrounded in sharp contrast by magnificent, densely wooded mountains.</blockquote>The episode of the attempt to steal wine, and others in this cheeky tradition, contains precious pearls of diction:<blockquote>The fact was, we were as broke as ever, retracing in our minds the smiles that had greeted my drunken antics, trying to find some trace of the irony with which we could identify the thief.</blockquote>A sense of strangeness returns. In the chapter “Circular Exploration”: “As night fell it brought us a thousand strange noises and the sensation of walking into empty space with each step.” In Episodes: “Then, in the middle of the ambush, an eerie moment of silence arose. When we went to gather the dead after the initial shooting, there was no one on the highway…” The imagery is fairly bursting with both the abundance and the silence of the visual world:<blockquote>The huge figure of a stag dashed like a quick breath across the stream and his body, silver by the light of the rising moon, disappeared into the undergrowth. This tremor of nature cut straight to our hearts. (The Motorcycle Diaries) [Fidel’s] voice and presence in the woods, lit up by the torches, took on moving tones, and you could see that our leader changed the ideas of many people. (Episodes)</blockquote>Though reference is made to Fidel’s voice and tone, the scene seems silent to us, as if it has been witnessed from afar. | |||

In these travel notes, several Quixotic or Chaplinesque episodes — such as the already cited theft of the wine, the nocturnal pursuit of the two young men “by a furious swarm of dancers,” their enlistment in a corps of Chilean firefighters, the delectable escapade of the melons and their trail over the waves, and the enigma of the impossible photo in a miserable hut on a hill near Caracas — are wrapped in a similar silence. | |||

La Poderosa’s near to last stand is told with cinematographic effect and we seem to be watching it all amid a film-like silence:<blockquote>I threw on the hand brake which, soldered ineptly, also broke. For some moments, I saw nothing more than the blurred shape of cattle flying past us on each side, while poor Poderosa gathered speed down the steep hill. By an absolute miracle we managed to graze only the leg of the last cow, but in the distance a river was screaming toward us with terrifying efficacy. I veered on to the side of the road and in the blink of an eye the bike mounted the two-meter bank, embedding us between two rocks, but we were unhurt.</blockquote>These youthful adventures — veined with cheerfulness, humor and frequently self-directed irony — seek the spirit of the landscape rather than merely the scenery. That “spirit” was found in the sudden appearance of the deer: “We walked slowly so as not to disturb the peace of the wild sanctuary with which we were now communing.” Che writes with none of the sarcasm he dedicates to the topic of religion: “Both [of us] assistants waited for Sunday [and the roast] with a kind of religious devotion.” So while being unbelievers, they were able to feel the metaphorical presence of a “sanctuary” in nature, where they were in close rapport with its “spirit” — immediately reminding us of analogous images from the freethinking Martí, such as this from his Simple Verses: “The bishop of Spain seeks / Supports for his shrine. / On wild mountain peaks / The poplars are mine.”‡‡ | |||

On March 7, 1952, in Valparaíso, they came face to face with injustice: its victim was an asthmatic old woman, a customer in a small shop by the name of La Gioconda:<blockquote>The poor thing was in a pitiful state, breathing the acrid smell of concentrated sweat and dirty feet that filled her room, mixed with the dust from a couple of armchairs, the only luxury items in her house. On top of her asthma, she had a heart condition.</blockquote>After completing a picture of total ruin, and further embittered by the animosity of the sick woman’s family, Che — who felt helpless as a doctor and was approaching the awakening of conscience that would trigger his other, definitive vocation — wrote these memorable words:<blockquote>It is there, in the final moments, for people whose farthest horizon has always been tomorrow, that one comprehends the profound tragedy circumscribing the life of the proletariat the world over. In those dying eyes there is a submissive appeal for forgiveness and also, often, a desperate plea for consolation which is lost to the void, just as their body will soon be lost in the magnitude of the mystery surrounding us.</blockquote>Unable to continue their journey any other way, the pair decided to stow away on a ship that would take them to Antofagasta, Chile. At that moment, they — or, at least, Che — did not see things so clearly:<blockquote>There [looking at the sea, leaning side by side on the railing of the San Antonio], we understood that our vocation, our true vocation, was to move for eternity along the roads and seas of the world. Always curious, looking into everything that came before our eyes, sniffing out each corner but only ever faintly—not setting down roots in any land or staying long enough to see the substratum of things; the outer limits would suffice.</blockquote>The sea held a greater attraction than the voyagers’ “road,” because where land demands that even those in passing take root, the sea represents absolute freedom from all ties. “And now, I feel my great roots unearth, free, and…” The verse that heads the chapter on his liberation from Chichina says it all. All? Che tore up another root in the presence of the old asthmatic Chilean woman. And soon his chest would be stung again when he made friends with a married Chilean couple, communist workers who had been harassed in Baquedano.<blockquote>The couple, numb with cold, in the desert night, huddling against each other in the desert night, were a living representation of the proletariat in any part of the world.</blockquote>Like good sons of San Martín,§§ they shared their blankets with them.<blockquote>It was one of the coldest times in my life, but also one which made me feel a little more brotherly toward this strange, for me at least, human species.</blockquote>That strangeness, that deep separation and intrepid solitude in which he was still wrapped, is curious. There is nothing lonelier than adventure. Until he was filled with pity for the galley slaves and for the whipped child, Don Quixote was alone, surrounded by strangeness, by the craziness of the world around him. In his Meditations on Quixote, José Ortega y Gasset wrote, as the center of his reflections, “I am myself and my circumstances,” which has usually been understood as the sum or symbiosis of two factors. It may also be understood as a dilemma in which the “I” or “myself” expresses those two factors as separated, distanced, though intensely related. This dilemma appeared in Che’s memoirs of his first “departure,” when he said:<blockquote>Although the blurred silhouette of the couple was nearly lost in the distance separating us, we could still see the man’s singularly determined face and we remembered his straightforward invitation: “Come, comrades, let’s eat together. I, too, am a tramp,” showing his underlying disdain for the parasitic nature he saw in our aimless traveling.</blockquote>Whose was this secret disdain: the humble worker’s or Che’s? Or perhaps neither, but that the meeting “in the desert night,” the sharing of the mate, bread, cheese and blankets, caused a spark which lit up a painful separation.<blockquote>At any rate, they were in Chuquicamata, with the mine and the miner from the south: Cold efficiency and impotent resentment go hand in hand in the big mine, linked in spite of the hatred by a common necessity to live, on the one hand, and to speculate on the other…</blockquote>An imposing suggestion appeared, and the leap to a kind of idea which would achieve its context, its possible meaning, years later in Cuba:<blockquote>…we will see whether some day, some miner will take up his pick in pleasure and go and poison his lungs with a conscious joy. They say that’s what it’s like over there, where the red blaze that now lights up the world comes from. So they say. I don’t know.</blockquote>In fact, in Cuba in 1964, Che would link these ideas with the words of the poet León Felipe (I don’t know if Che was familiar with them when writing the lines above): “No one has yet been able to dig to the rhythm of the sun… no one has cut an ear of corn with love and grace.”<blockquote>I quote these words because today we could tell that great, desperate poet to come now to Cuba; to see how human beings, after passing through all of the stages of capitalist alienation and after thinking of themselves as beasts of burden harnessed to the yoke of the exploiter, have rediscovered their path and have found their way back to play. Now, in our Cuba, work is acquiring a new meaning and is done with a new joy.***</blockquote>Yet in March 1952, Che simply wrote, “we will see.” The harsh lessons continued in the chapter “Chuquicamata,” named after the mining town that was “like a scene from a modern drama,” and which he soberly described with a balance of impression, reflection and data. Its greatest lesson was “taught by the graveyards of the mines, containing only a small share of the immense number of people devoured by cave-ins, silica and the hellish climate of the mountain.” In his note of March 22, 1952, or some time later revising his notes, Che concluded: “The biggest effort Chile should make is to shake its uncomfortable Yankee friend from its back, a task that for the moment at least is Herculean.” The name Salvador Allende stops us in our tracks. | |||

On the motorcycle, on trucks or in vans, on a ship or in a little Ford; sleeping in police stations, under the stars or in occasional shelters; Che struggling almost constantly with his asthma, the two friends crossed Argentina and Chile. They entered Peru on foot. The Peruvian Indians had a huge impact on them, just as the Mexican Indians had impressed Martí:<blockquote>These people who watch us walk through the streets of the town are a defeated race. Their stares are tame, almost fearful, and completely indifferent to the outside world. Some give the impression they go on living only because it’s a habit they cannot shake.</blockquote>They come to the kingdom of defeated stone, Pachamama’s kingdom, Mother Earth, who receives the spat-out “chewed coca leaves instead of stones” with their accompanying “troubles.” The center or navel of the world, where Mama Ocllo dropped her golden wedge into the earth. The place Viracocha chose: Cuzco. And there, in the middle of the baroque procession of Our Lord of the Earthquakes, “a brown Christ,” they find an eternal reminder of the north which can only be seen from South America, its fatal and denouncing antithesis:<blockquote>Standing over the small frames of the Indians gathered to see the procession pass, the blond head of a North American can occasionally be glimpsed. With his camera and sports shirt, he seems to be (and in fact, actually is) a correspondent from another world…</blockquote>The cathedral of Cuzco brought out the artist in Che, with such observations as this: “Gold doesn’t have the gentle dignity of silver which becomes more charming as it ages, and so the cathedral seems to be decorated like an old woman with too much makeup.” Of the many churches he visited, he was particularly struck by the lonely, disreputable and “pitiful image of the bell towers of the Church of Belén, toppled by the earthquake, lying like dismembered animals on the hillside.” But his most penetrating judgment of Peruvian colonial baroque is found in the lines of his sharply contrasting description of Lima’s cathedral:<blockquote>There in Lima, the art is more stylized, with an almost effeminate touch: the cathedral towers are tall and graceful, maybe the most slender of all the cathedrals in the Spanish colonies. The lavishness of the woodwork in Cuzco has been left behind and taken up here in gold. The naves are light and airy, contrasting with those dark, hostile caverns of the Inca city. The paintings are also bright, almost joyous, and of schools more recent than the hermetic mestizos, who painted their saints with a dark and captive fury.</blockquote>Their visit to Machu Picchu on April 5 served as the subject for a newspaper article that Che published in Panama on December 12, 1953, in which there is a careful gathering of data and historical information, and a didactic intention that was absent from his personal notes. | |||

Something similar occurred in an article entitled “A Glance at the Banks of the Giant of Rivers,” which was also published in Panama, on November 22, 1953, though in this Che placed greater emphasis on experience, describing his journey down the Amazon on a raft. The raft, humorously christened Mambo-Tango — so they wouldn’t be accused of being fanatics about the latter — enabled Che and Alberto, with a lot of hard work and danger, to learn about the harsh reality of the Amazonian Indians. | |||

From the solitary heights of the “enigmatic stone blocks” to the debilitating neglect they witnessed on the banks of the Amazon, it was like traveling through a genetic map of the Americas. Celebrating his 24th birthday in the leper colony of San Pablo, Che spoke, in a style reminiscent of Bolívar and Martí: “We constitute a single mestizo race, which from Mexico to the Magellan Straits bears notable ethnographic similarities. And so, in an attempt to rid myself of the weight of smallminded provincialism, I propose a toast to Peru and to a United Latin America.” | |||

There was no hint of solemnity in these words; rather, pretending his words were merely rhetorical, he spoke with a confidence that placed them outside all convention: “My oratory offering was received with great applause.” He did the same in a letter that he wrote to his mother from Bogotá on July 6, 1952, (included here to complete the description of his Colombian experiences), when he referred once again to his “Pan-American speech,” which won “great applause from the notable, and notably drunk, audience,” and when he commented, with affectionate sarcasm, on Granado’s own words of gratitude: “Alberto, who believes he is Perón’s natural heir, delivered such an impressive, demagogic speech that our well-wishers were convulsed with laughter.” But he spoke in a very different tone of the lepers and their lives, using moderation to try — in vain — to hide his own suffering. Writing about their departure from the San Pablo leper colony, Che said:<blockquote>That night an assembly of the colony’s patients gave us a farewell serenade, with lots of local songs sung by a blind man. The orchestra was made up of a flute player, a guitarist and an accordion player with almost no fingers, and a “healthy” contingent helping out with a saxophone, a guitar and some percussion. After that came the time for speeches, in which four patients spoke as well as they could, a little awkwardly. One of them froze, unable to go on, until out of desperation he shouted, “Three cheers for the doctors!” Afterwards, Alberto thanked them warmly for their welcome…</blockquote>Che described the scene in detail in the letter to his mother, (“an accordion player with no fingers on his right hand used little sticks tied to his wrist” and “almost all the others were horribly deformed, due to the nervous form of the disease”), trying unsuccessfully not to sadden her too much, comparing it with a “scene from a horror movie,” but the tearing beauty of that farewell was clear:<blockquote>The patients cast off and to the sound of a folk tune the human cargo drifted away from shore; the faint light of their lanterns giving the people a ghostly quality.</blockquote>From his notes on their experiences with the lepers, for whom they surely did much good, not only by treating them but also by playing soccer and talking with them in the spirit of unprejudiced, fraternal, intense humanity — explaining the lepers’ immense gratitude — we can perceive the origins of the budding revolutionary in Che. I emphasize these words: “If there’s anything that will make us seriously dedicate ourselves to leprosy, it will be the affection shown to us by all the sick we’ve met along the way.” Impossible to imagine at the time how serious and deep that dedication would be, understanding “leprosy” to mean all of human misery. | |||

Having read these notes, filled with so many contrasts and teachings, with so much comedy and tragedy, like life itself, and having commented — not exhaustively, but only as suggestions — I conclude with the joyous image of Che arriving in Caracas, wrapped in his traveling blanket, staring around him at the Latin American panorama, “muttering all sorts of verses, lulled by the roar of the truck.” | |||

I’ll leave you with no further commentary, because, in its terrible, unadorned majesty, that exceptional final chapter “A Note in the Margin” neither needs nor tolerates it. In fact, I’m not sure whether this unfathomable “revelation” should be placed at the beginning or the end of these “diaries”; the revelation Che saw “printed in the night sky”; his own fate; waiting for “the great guiding spirit to cleave humanity into two antagonistic halves”; the Great Semí who, in Martí’s view of Our America, would go “astride its condor, spreading the seed of the new America through the romantic nations of the continent and the sorrowful islands of the sea.”††† It is an inexorable chapter that, like a tragic flash of lightning, illuminates for us the “sacred space” in the depths of the soul of one who called himself “this small soldier of the 20th century.” Of one who, in our invincible hope, always takes “to the road” again, shield on his arm and feeling “the ribs of Rocinante”‡‡‡ beneath his heels. | |||

<nowiki>*</nowiki> Simón Bolívar led several armed rebellions, helping to win independence from Spain for much of Latin America. His vision was for a federation of Spanish-speaking South American states. | |||

† The ravine in which Che’s guerrilla unit was ambushed on October 8, 1967, and Che himself taken hostage. He was murdered the following day. | |||

‡ José Martí, Cuban national hero and noted poet, writer, speaker and journalist. Martí founded the Cuban Revolutionary Party in 1892 to fight Spanish rule and oppose U.S. neocolonialism. He launched the 1895 independence war and was killed in battle. | |||

§ José Martí, Obras completas (Complete Works),Havana: Editorial Nacional de Cuba, 1963–73, vol.7, pp.289–90. | |||

<nowiki>**</nowiki> From Ernesto Che Guevara, Episodes of the Revolutionary War, forthcoming from Ocean Press, 2004. Also in Ernesto Che Guevara, Che Guevara Reader, Ocean Press, 2003, p.37. | |||

†† Ezequiel Martínez Estrada, Martí revolucionario (Martí the Revolutionary), Havana: Casa de las Américas, 1967, p.414, no.184. | |||

‡‡ José Martí, Op. cit., vol.16, p.68. | |||

§§ José de San Martín, Argentine national hero who played a major role in winning independence from Spain for Argentina, Chile and Peru. | |||

<nowiki>***</nowiki> Ernesto Che Guevara, Obras, 1957–67 (Works, 1957–67),Havana: Casa de las Américas, 1970, vol.II, p.333. | |||

††† José Martí, José Martí Reader, Ocean Press, 1999, p.120. | |||

‡‡‡ .Che Guevara Reader, p.384. | |||

== Entendámonos/So we understand each other == | |||

This is not a story of heroic feats, or merely the narrative of a cynic; at least I do not mean it to be. It is a glimpse of two lives running parallel for a time, with similar hopes and convergent dreams. | |||

In nine months of a man’s life he can think a lot of things, from the loftiest meditations on philosophy to the most desperate longing for a bowl of soup — in total accord with the state of his stomach. And if, at the same time, he’s somewhat of an adventurer, he might live through episodes of interest to other people and his haphazard record might read something like these notes. | |||

And so, the coin was thrown in the air, turning many times, landing sometimes heads and other times tails. Man, the measure of all things, speaks here through my mouth and narrates in my own language that which my eyes have seen. It is likely that out of 10 possible heads I have seen only one true tail, or vice versa. In fact it’s probable, and there are no excuses, for these lips can only describe what these eyes actually see. Is it that our whole vision was never quite complete, that it was too transient or not always well-informed? Were we too uncompromising in our judgments? Okay, but this is how the typewriter interpreted those fleeting impulses raising my fingers to the keys, and those impulses have now died. Moreover, no one can be held responsible for them. | |||

The person who wrote these notes passed away the moment his feet touched Argentine soil again. The person who reorganizes and polishes them, me, is no longer, at least I am not the person I once was. All this wandering around “Our America with a capital A” has changed me more than I thought. | |||

In any photographic manual you’ll come across the strikingly clear image of a landscape, apparently taken by night, in the light of a full moon. The secret behind this magical vision of “darkness at noon” is usually revealed in the accompanying text. Readers of this book will not be well versed about the sensitivity of my retina — I can hardly sense it myself. So they will not be able to check what is said against a photographic plate to discover at precisely what time each of my “pictures” was taken. What this means is that if I present you with an image and say, for instance, that it was taken at night, you can either believe me, or not; it matters little to me, since if you don’t happen to know the scene I’ve “photographed” in my notes, it will be hard for you to find an alternative to the truth I’m about to tell. But I’ll leave you now, with myself, the man I used to be… | |||

== Pródromos/Forewarnings == | |||

It was a morning in October. Taking advantage of the holiday on the 17th I had gone to Córdoba.* We were at Alberto Granado’s place under the vine, drinking sweet mate† and commenting on recent events in this “bitch of a life,” tinkering with La Poderosa II.‡ Alberto was lamenting the fact that he had to quit his job at the leper colony in San Francisco del Chañar and about how poor his pay was now at the Español Hospital. I had also quit my job, but unlike Alberto I was very happy to leave. I was feeling uneasy, more than anything because having the spirit of a dreamer I was particularly jaded with medical school, hospitals and exams. | |||

Along the roads of our daydream we reached remote countries, navigated tropical seas and traveled all through Asia. And suddenly, slipping in as if part of our fantasy, the question arose: | |||

“Why don’t we go to North America?” | |||

“North America? But how?” | |||

“On La Poderosa, man.” | |||

The trip was decided just like that, and it never erred from the basic principle laid down in that moment: improvisation. Alberto’s brothers joined us in a round of mate as we sealed our pact never to give up until we had realized our dream. So began the monotonous business of chasing visas, certificates and documents, that is to say, of overcoming the many hurdles modern nations erect in the paths of would-be travelers. To save face, just in case, we decided to say we were going to Chile. | |||

My most important mission before leaving was to take exams in as many subjects as possible; Alberto’s to prepare the bike for the long journey, and to study and plan our route. The enormity of our endeavor escaped us in those moments; all we could see was the dust on the road ahead and ourselves on the bike, devouring kilometers in our flight northward. | |||

<nowiki>*</nowiki> At the time a national holiday to commemorate Juan Perón’s 1945 release from prison. General Perón was president of Argentina from 1946 to 1955 and from 1973 until his death in 1974. | |||

† The Argentine national drink, a tea-like beverage made from the herb mate. | |||

‡ Granado’s Norton 500 motorcycle, literally “The Mighty One." | |||

Revision as of 01:16, 24 April 2024

The Motorcycle Diaries | |

|---|---|

| Author | Ernesto Guevara |

| Written in | 1950s |

| First published | 1995 |

| Type | Diary |

Contents

Preface by Aleida Guevara

Preface to the first edition by Aleida March

Biography of Ernesto Che Guevara

Brief chronology of Ernesto Che Guevara

Map and Itinerary of The Motorcycle Diaries

Introduction by Cintio Vitier

The Motorcycle Diaries

So we understand each other

Forewarnings

Discovery of the ocean

...Lovesick pause

Until the last tie is broken

For the flu, bed

San Martin de los Andes

Circular exploration

Dear Mama

On the Seven Lakes Road

An now, I feel my great roots unearth, free and...

Objects of curiosity

The Experts

The difficulties intensify

La Poderosa II's final tour

Firefighters, workers and other matters

La Gioconda's smile

Stowaways

This time, disaster

Chuquicamata

Arid land for miles and miles

The end of Chile

Chjle, a vision from afar

Tarata, the new world

In the dominions of Pachamama

Lake of the sun

Toward the navel of the world

The navel

The land of the Incas

Out Lord of the Earthquakes

Homeland for the victor

Cuzco straight

Huambo

Ever northward

Through the center of Peru

Shattered hopes

The city of the viceroys

Down the Ucayali

Dear Papi

The San Pablo leper colony

Saint Guevara's day

Dear Mama

On the road to Caracas

This strange 20th century

A note in the margin

Preface by Aleida Guevara

When I read these notes for the first time, they were not yet in book form and I did not know the person who had written them. I was much younger then and I identified immediately with this man who had narrated his adventures in such a spontaneous way. Of course, as I continued reading, I began to see more clearly who this person was and I was very glad to be his daughter.

It is not my aim to tell you anything of what you will discover as you read, but I do not doubt that when you have finished the book you will want to go back to enjoy some passages again, either for the beauty they describe or the intensity of the feelings they convey.

There were moments when I literally took over Granado’s place on the motorbike and clung to my dad’s back, journeying with him over the mountains and around the lakes. I admit there were some occasions when I left him to himself, especially at those times when he writes so graphically things I would never talk about myself. When he does, however, he reveals yet again just how honest and unconventional he could be.

To tell you the truth, I should say that the more I read, the more in love I was with the boy my father had been. I do not know if you will share these sentiments with me, but while I was reading, I got to know the young Ernesto better: the Ernesto who left Argentina with his yearning for adventure and his dreams of the great deeds he would perform, and the young man who, as he discovered the reality of our continent, continued to mature as a human being and to develop as a social being.

Slowly we see how his dreams and ambitions changed. He grew increasingly aware of the pain of many others and he allowed it to become a part of himself.

The young man, who makes us smile at the beginning with his absurdities and craziness, becomes before our eyes increasingly sensitive as he tells us about the complex indigenous world of Latin America, the poverty of its people and the exploitation to which they are submitted. In spite of it all, he never loses his sense of humor, which instead becomes finer and more subtle.

My father, “ése, el que fue” (“myself, the man I used to be”), shows us a Latin America that few of us know about, describing its landscapes with words that color each image and reach into our senses, so that we too can see the things his eyes took in.

His prose is fresh. His words allow us to hear sounds we have never heard before, infusing us with the surroundings that struck this romantic being with their beauty and their crudity, yet he never loses his tenderness even as he becomes firmer in his revolutionary longing. His awareness grows that what poor people need is not so much his scientific knowledge as a physician, but rather his strength and persistence in trying to bring about the social change that would enable them to live with the dignity that had been taken from them and trampled on for centuries.

This young adventurer with his thirst for knowledge and his great capacity to love shows us how reality, if properly interpreted, can permeate a human being to the point of changing his or her way of thinking.

Read these notes of his that were written with so much love, eloquence and sincerity, these notes that more than anything else make me feel closer to my father. I hope you enjoy them and that you can join him on his journey.

If you ever have the opportunity to follow his footsteps in reality, you will discover with sadness that many things remain unchanged or are even worse, and this is a challenge for those of us who — like this young man who years later would become Che — are sensitive to the reality that so mistreats the most wretched among us, those of us who have a commitment to helping create a world that is much more just.

I shall leave you now with the man I knew, the man I love intensely for the strength and tenderness he demonstrated in the way he lived.

Enjoy your reading! Ever onward!

Aleida Guevara March

July 2003

Preface to the First Edition

Ernesto Guevara’s travel diaries, transcribed by Che’s Personal Archive in Havana,* recount the trials, vicissitudes and tremendous adventure of a young man’s journey of discovery through Latin America. Ernesto began writing these diaries when, in December 1951, he set off with his friend Alberto Granado on their long-awaited trip from Buenos Aires, down the Atlantic coast of Argentina, across the pampas, through the Andes and into Chile, and from Chile northward to Peru and Colombia and finally to Caracas.

These experiences were later rewritten by Ernesto himself in narrative form, offering the reader a deeper insight into Che’s life, especially at a little known stage, and revealing details of his personality, his cultural background and his narrative skill — the genesis of a style which develops in his later works. The reader can also witness the extraordinary change which takes place in him as he discovers Latin America, gets right to its very heart and develops a growing sense of a Latin American identity, ultimately making him a precursor of the new history of America.

Aleida March

Che’s Personal Archive

Havana, Cuba, 1993

*Now the Che Guevara Studies Center of Havana, Cuba.

Biography of Ernesto "Che" Guevara

One of Time magazine’s “icons of the century,” Ernesto Guevara de la Serna was born in Rosario, Argentina, on June 14, 1928. He made several trips around Latin America during and immediately after his studies at medical school in Buenos Aires, including his 1952 journey with Alberto Granado, on the unreliable Norton motorbike La Poderosa II described in this travel diary.

He was already becoming involved in political activity and living in Guatemala when, in 1954, the democratically elected government of Jacobo Árbenz was overthrown in the CIA-organized military operation. Ernesto escaped to Mexico, profoundly radicalized.

Following up on a contact made in Guatemala, Guevara sought out a group of exiled Cuban revolutionaries in Mexico City. In July 1955, he met Fidel Castro and immediately enlisted in the Cuban guerrilla expedition to overthrow the dictator Fulgencio Batista. The Cubans nicknamed Ernesto “Che,” a popular form of address in Argentina.

On November 25, 1956, Guevara set sail for Cuba aboard the yacht Granma as the doctor to the guerrilla group that began the revolutionary armed struggle in Cuba’s Sierra Maestra mountains. Within several months, he had become the first Rebel Army commander, though he continued treating wounded guerrilla fighters and captured soldiers from Batista’s army.

In September 1958, Guevara played a decisive role in the military defeat of Batista after he and Camilo Cienfuegos led separate guerrilla columns westward from the Sierra Maestra.

After Batista fled on January 1, 1959, Guevara became a key leader of the new revolutionary government, first as head of the Department of Industry of the National Institute of Agrarian Reform, then as president of the National Bank. In February 1961 he became minister of industry. He was also a central leader of the political organization that in 1965 became the Communist Party of Cuba.

Apart from these responsibilities, Guevara represented the Cuban revolutionary government around the world, heading several delegations and speaking at the United Nations and other international forums in Asia, Africa, Latin America and the socialist bloc countries. He earned a reputation as a passionate and articulate spokesperson for Third World peoples, most famously at the Organization of American States (OAS) conference at Punta del Este in Uruguay, where he denounced U.S. President Kennedy’s Alliance for Progress.

As had been his intention since joining the Cuban revolutionary movement, Guevara left Cuba in April 1965, initially to lead a guerrilla mission to support the revolutionary struggle in the Congo. He returned to Cuba secretly in December 1965, to prepare another guerrilla force for Bolivia. Arriving in Bolivia in November 1966, Guevara’s plan was to challenge that country’s military dictatorship and eventually instigate a revolutionary movement that would extend throughout the continent of Latin America. He was wounded and captured by U.S.-trained-and-run Bolivian counter-insurgency troops on October 8, 1967. The following day he was murdered and his body hidden.

Che Guevara’s remains were finally discovered in 1997 and returned to Cuba. A memorial was built at Santa Clara in central Cuba, where he had won a major military battle during the Cuban revolutionary war.

Brief Chronology of Ernesto "Che" Guevara

1928

Ernesto Guevara is born on June 14 in Rosario, Argentina. He is the first child of middle-class parents Ernesto Guevara Lynch and Celia de la Serna.

1932

The Guevara family moves from Buenos Aires to Alta Gracia, a spa town near Córdoba, on account of Ernesto’s chronic asthma. His asthma also prevents him from regular attendance at school until he is nine years old.

1948

Altering his initial plan to study engineering, Ernesto enrolls in medical school at the University of Buenos Aires, while holding a series of part-time jobs, including in an allergy treatment clinic.

1950

Ernesto sets out on a 4,500 kilometer trip around the north of Argentina on a motorized bicycle.

1951-52

In October 1951, Ernesto and his friend Alberto Granado decide on a plan to ride Alberto’s motorbike (La Poderosa II — The Mighty One) to North America. Granado is a biochemist who had specialized in leprology and whose younger brothers had been Ernesto’s school friends. They leave Córdoba in December, heading first to farewell Ernesto’s family in Buenos Aires. The adventures experienced on this trip, written up by Ernesto during and after the journey, comprise this book, published first as Notas de Viaje (Travel Notes or The Motorcycle Diaries).

1953

Ernesto graduates as a doctor and almost immediately embarks on another journey around Latin America which takes in Bolivia, Peru, Ecuador, Panama, Costa Rica and Guatemala, where he meets Antonio (Ñico) López, a young Cuban revolutionary. In Bolivia, he is witness to the Bolivian Revolution. The account of these travels was first published as Otra Vez (in English, Latin America Diaries).

1954

Ernesto’s political views are profoundly radicalized when in Guatemala he sees the overthrow of the democratically elected government of Jacobo Arbenz by U.S.-backed forces. He escapes to Mexico where he contacts the group of Cuban revolutionary exiles. In Mexico, he marries Peruvian Hilda Gadea, with whom he has a daughter, Hildita.

1955

After meeting Fidel Castro, he agrees to join the group being organized to wage guerrilla war against the Batista dictatorship. Now called “Che” by the Cubans — a common nickname for Argentines — in November 1956 he sails as the troop’s doctor on the yacht Granma.

1956-58

Che soon demonstrates outstanding military ability and is promoted to the rank of commander in July 1957. In December 1958, he leads the Rebel Army to a decisive victory over Batista’s forces at Santa Clara in central Cuba.

1959

In February, Che is declared a Cuban citizen in recognition of his contribution to the island’s liberation. He marries Aleida March, with whom he has four children. In October, he is appointed head of the Industrial Department of the Institute of Agrarian Reform and in November becomes President of the National Bank of Cuba. With a gesture of disdain for money, he signs the new banknotes simply as “Che.”

1960

Representing the revolutionary government, Che undertakes an extensive trip to the Soviet Union, the German Democratic Republic, Czechoslovakia, China and North Korea, signing several key trade agreements.

1961

Che is appointed head of the newly established Ministry of Industry. In August, he heads Cuba’s delegation to the Organization of American States (OAS) at Punta del Este, Uruguay, where he denounces U.S. President Kennedy’s Alliance for Progress.

1962

A fusion of Cuban revolutionary organizations takes place and Che is elected to the National Directorate. Che visits the Soviet Union for the second time.

1963

Che travels to Algeria, which has just won independence from France under the government of Ahmed Ben Bella.

1964

Before heading off for an extensive trip around Africa, Che addresses the UN General Assembly in December.

1965

Che leads an international mission to the Congo to support the liberation movement founded by Patrice Lumumba. Responding to mounting speculation about Che’s whereabouts, Fidel Castro reads Che’s farewell letter to the Central Committee of the newly founded Cuban Communist Party. In December, Che returns to Cuba to prepare in secret for a new mission to Bolivia.

1966

In November, Che arrives in Bolivia in disguise.

1967

In April, Che’s “Message to the Tricontinental” is published, calling for the creation of “two, three, many Vietnams.” The same month, part of his guerrilla group becomes separated from the main detachment. On October 8, the remaining 17 guerrillas are ambushed and Che is wounded and captured. The following day he is murdered by Bolivian forces acting under instructions from Washington. His remains are buried in an unmarked grave along with the bodies of several other guerrilla fighters. October 8 is designated the Day of the Heroic Guerrilla in Cuba.

1997

Che’s remains are finally located in Bolivia and returned to Cuba, where they are placed in a memorial at Santa Clara.

Map and Itinerary

Map of the Motorcycle Diaries

Itinerary of the Motorcycle Diaries

ARGENTINA

1951

December Córdoba to Buenos Aires

1952

January 4 Leave Buenos Aires

January 6 Villa Gesell

January 13 Miramar

January 14 Necochea

January 16–21 Bahía Blanca

January 22 En route to Choele Choel

January 25 Choele Choel

January 29 Piedra del Águila

January 31 San Martín de los Andes

February 8 Nahuel Huapí

February 11 San Carlos de Bariloche

CHILE

February 14 Take the Modesta Victoria to Peulla

February 18 Temuco

February 21 Lautaro

February 27 Los Ángeles

March 1 Santiago de Chile

March 7 Valparaíso

March 8–10 Aboard the San Antonio

March 11 Antofagasta

March 12 Baquedano

March 13–15 Chuquicamata

March 20 Iquique (and the Toco, La Rica Aventura and Prosperidad Nitrate Companies)

March 22 Arica

PERU

March 24 Tacna

March 25 Tarata

March 26 Puno

March 27 Sail on Lake Titicaca

March 28 Juliaca

March 30 Sicuani

March 31 – April 3 Cuzco

April 4–5 Machu Picchu

April 6–7 Cuzco

April 11 Abancay

April 13 Huancarama

April 14 Huambo

April 15 Huancarama

April 16–19 Andahuaylas

April 22–24 Ayacucho to Huancallo

April 25–26 La Merced

April 27 Between Oxapampa and San Ramón

April 28 San Ramón

April 30 Tarma

May 1–17 Lima

May 19 Cerro de Pasco

May 24 Pucallpa

May 25–31 Aboard La Cenepa sailing down Río Ucayali, a tributary of the Amazon

June 1–5 Iquitos

June 6–7 Aboard El Cisne sailing to the leper colony of San Pablo

June 8–20 San Pablo

June 21 Aboard the Mambo-Tango raft on the Amazon

COLOMBIA

June 23 – July 1 Leticia

July 2 Leave Leticia by plane

July 2–10 Bogotá

July 12–13 Cúcuta

VENEZUELA

July 14 San Cristóbal

July 16 Between Barquisimeto and Corona

July 17–26 Caracas, where Che and Alberto separate

UNITED STATES

Late July Miami

ARGENTINA

August Che returns to his family in Córdoba

Introduction by Cintio Vitier

If there is one hero in Latin America’s struggle for liberation — stretching from Bolívar’s* time until our own —who has attracted young people from Latin America and from all over the world, that hero is Ernesto Che Guevara. And though since his death he has become a modern myth, he has not yet been stripped of his youthful vitality. To the contrary, his mythic status has only served to heighten his youthfulness which, together with his daring and his purity, seem to constitute the secret essence of his charisma.

Becoming a myth, a symbol of so many scattered and fiercely held hopes, presupposes that such a character possesses a kind of gravity, a certain solemnity. It is good that this is so; historic utopia needs faces to embody it. But we shouldn’t lose sight of the everyday nature of those human beings, who were children, teenagers and young people before they acquired the skills by which to guide us. It is not that I want to bury their exceptional natures in the common or familiar aspects of their lives, but that knowledge of those first, formative stages shows us the starting point for their later trajectories

This is especially true in Che’s case, whose account of this first trip he made with his friend Alberto Granado offers the young at heart such a close and cheerful, serious and at the same time ironic image of the young man, that we can almost glimpse his smile and hear his voice and asthmatic wheeze. He is young, like them, and he filled his whole life with youthfulness and matured his youth without diluting it.

This edition of The Motorcycle Diaries, the notes describing a journey made without hesitation, aboard the noisy motorcycle La Poderosa II (which gave out halfway, but only after transmitting to the adventure a joyous impulse we, too, receive), free as the wind, with the sole purpose of getting to know the world, is dedicated to people whose youth is not merely sequential, but wholehearted and spiritual.

In the first pages, the young man who would become one of the genuine heroes of the 20th century cautions us, “This is not a story of heroic feats.” The word “heroic” rings out above the others, because we cannot read these pages without thinking of Che’s future, an image of him in the Sierra Maestra, an image which reached perfection at Quebrada del Yuro in Bolivia.†

If this youthful adventure had not been prelude to his revolutionary formation, these pages would be different, and we would read them differently, though we cannot imagine how. Simply knowing that they are Che’s — though he wrote them before becoming Che — makes us believe that he had a presentiment regarding the way they should be read. For example:

The person who wrote these notes passed away the moment his feet touched Argentine soil again. The person who reorganizes and polishes them, me, is no longer, at least I’m not the person I once was. All this wandering around “Our America with a capital A” has changed me more than I thought.

These pages are a testimony — a photographic negative, as he also put it — of an experience that changed him, a first “departure” toward the outer world which, like his final departure, was Quixotic in its semi-unconscious style and, as for Quixote, had the same effect on the scope of his consciousness. This was the “spirit of a dreamer” experiencing an awakening.

In principle, and with the perfect logic of the unforeseeable, their journey was at first directed toward North America, as in fact it turned out to be: toward the “photographic negative” of North America that is South American poverty and helplessness, and toward real knowledge of what North America means for us.

“The enormity of our endeavor escaped us in those moments; all we could see was the dust on the road ahead and ourselves on the bike, devouring kilometers in our flight northward.” Wasn’t that “dust on the road,” though without Che realizing it, really the same dust José Martí‡ saw when he traveled from La Guaira to Caracas “in a common little coach”? Wasn’t it the Quixotic dust in which the ghosts of American redemption appeared, “the natural cloud of dust that must rise when our terrible casing of chains falls to the ground”?§ But Martí was coming from the north, and Che was traveling toward himself, catching only glimpses of his destiny, which we glimpse as well through his anecdotes and vignettes.

Comeback, the little dog with “aviator’s impulses” Che presents to us so comically, leaping around the motorcycle from Villa Gesell to Miramar, reappears years later in the Sierra Maestra mountains as a puppy who must be strangled, because of its “hysterical howls” during an unsuccessful ambush laid in the hope of catching [Batista’s notorious army colonel] Sánchez Mosquera. “With one last nervous twitch, the puppy stopped moving. There it lay, sprawled out, its little head spread over the twigs.”** But, at the end of this incident from Episodes of the Revolutionary War, another dog appears lying in the hamlet of Mar Verde:

Félix patted its head, and the dog looked at him. Félix returned the glance, and then he and I exchanged a guilty look. Suddenly everyone fell silent. An imperceptible stirring came over us, as the dog’s meek yet roguish gaze seemed to contain a hint of reproach. There, in our presence, though observing us through the eyes of another dog, was the murdered puppy

It was Comeback who had returned, living up to his name, reminding us also of what Ezequiel Martínez Estrada, our other great Argentine, said about José Martí’s campaign diary:

These emotions, these sensations, cannot be described or expressed in the language of poets and painters, musicians and mystics; they must be… absorbed without reply, as animals do with their contemplative and entranced eyes.††

A comparison of Episodes with The Motorcycle Diaries shows us that, even though more than 10 years had passed, the latter was a literary model for the former. It contains the same moderation; the same candor; the same nimble freshness; exactly the same concept of moments used to provide unity for each brief chapter; and, of course, the same imperturbable steadiness that accepts both happy and tragic events without sharp inhalation or exhalation.

It isn’t literary skill but fidelity to experience and narrative effectiveness that is sought. When both are attained, skill follows naturally, taking its allotted place, neither blinding nor disturbing but making its contribution. Here, with little fumbling or hesitation, Che’s style is already formed. The years would polish it, just as he himself polished his will with the pleasure of an artist, though not that of a wordsmith: a quiet shyness forced him not to dwell too much but to push on with the words toward the poetry of the naked image, which his minimal touch turned into reality. His “I—it-inme” circle opens and closes continually without ever becoming dense, accommodating a style that prefers to remain hidden. The prose on the page sheds light, though does not drag on the imperceptible lightness of the narrative. It flows between description of feeling (in Episodes, “the determined murderer left a trail of burned huts, of sullen sadness…”) and narrative accounts in which he searches for himself (in the Diaries, “Man, the measure of all things, speaks here through my mouth and narrates in my own language that which my eyes have seen”) and sometimes even seems to be watching us.

Che’s colorful prose paints objects as far as his eyes can see and often, if the landscape permits it, with an intimate touch:

The road snakes between the low foothills that sound the beginning of the great cordillera of the Andes, then descends steeply until it reaches an unattractive, miserable town, surrounded in sharp contrast by magnificent, densely wooded mountains.

The episode of the attempt to steal wine, and others in this cheeky tradition, contains precious pearls of diction:

The fact was, we were as broke as ever, retracing in our minds the smiles that had greeted my drunken antics, trying to find some trace of the irony with which we could identify the thief.

A sense of strangeness returns. In the chapter “Circular Exploration”: “As night fell it brought us a thousand strange noises and the sensation of walking into empty space with each step.” In Episodes: “Then, in the middle of the ambush, an eerie moment of silence arose. When we went to gather the dead after the initial shooting, there was no one on the highway…” The imagery is fairly bursting with both the abundance and the silence of the visual world:

The huge figure of a stag dashed like a quick breath across the stream and his body, silver by the light of the rising moon, disappeared into the undergrowth. This tremor of nature cut straight to our hearts. (The Motorcycle Diaries) [Fidel’s] voice and presence in the woods, lit up by the torches, took on moving tones, and you could see that our leader changed the ideas of many people. (Episodes)

Though reference is made to Fidel’s voice and tone, the scene seems silent to us, as if it has been witnessed from afar.

In these travel notes, several Quixotic or Chaplinesque episodes — such as the already cited theft of the wine, the nocturnal pursuit of the two young men “by a furious swarm of dancers,” their enlistment in a corps of Chilean firefighters, the delectable escapade of the melons and their trail over the waves, and the enigma of the impossible photo in a miserable hut on a hill near Caracas — are wrapped in a similar silence.

La Poderosa’s near to last stand is told with cinematographic effect and we seem to be watching it all amid a film-like silence:

I threw on the hand brake which, soldered ineptly, also broke. For some moments, I saw nothing more than the blurred shape of cattle flying past us on each side, while poor Poderosa gathered speed down the steep hill. By an absolute miracle we managed to graze only the leg of the last cow, but in the distance a river was screaming toward us with terrifying efficacy. I veered on to the side of the road and in the blink of an eye the bike mounted the two-meter bank, embedding us between two rocks, but we were unhurt.

These youthful adventures — veined with cheerfulness, humor and frequently self-directed irony — seek the spirit of the landscape rather than merely the scenery. That “spirit” was found in the sudden appearance of the deer: “We walked slowly so as not to disturb the peace of the wild sanctuary with which we were now communing.” Che writes with none of the sarcasm he dedicates to the topic of religion: “Both [of us] assistants waited for Sunday [and the roast] with a kind of religious devotion.” So while being unbelievers, they were able to feel the metaphorical presence of a “sanctuary” in nature, where they were in close rapport with its “spirit” — immediately reminding us of analogous images from the freethinking Martí, such as this from his Simple Verses: “The bishop of Spain seeks / Supports for his shrine. / On wild mountain peaks / The poplars are mine.”‡‡ On March 7, 1952, in Valparaíso, they came face to face with injustice: its victim was an asthmatic old woman, a customer in a small shop by the name of La Gioconda:

The poor thing was in a pitiful state, breathing the acrid smell of concentrated sweat and dirty feet that filled her room, mixed with the dust from a couple of armchairs, the only luxury items in her house. On top of her asthma, she had a heart condition.

After completing a picture of total ruin, and further embittered by the animosity of the sick woman’s family, Che — who felt helpless as a doctor and was approaching the awakening of conscience that would trigger his other, definitive vocation — wrote these memorable words:

It is there, in the final moments, for people whose farthest horizon has always been tomorrow, that one comprehends the profound tragedy circumscribing the life of the proletariat the world over. In those dying eyes there is a submissive appeal for forgiveness and also, often, a desperate plea for consolation which is lost to the void, just as their body will soon be lost in the magnitude of the mystery surrounding us.

Unable to continue their journey any other way, the pair decided to stow away on a ship that would take them to Antofagasta, Chile. At that moment, they — or, at least, Che — did not see things so clearly:

There [looking at the sea, leaning side by side on the railing of the San Antonio], we understood that our vocation, our true vocation, was to move for eternity along the roads and seas of the world. Always curious, looking into everything that came before our eyes, sniffing out each corner but only ever faintly—not setting down roots in any land or staying long enough to see the substratum of things; the outer limits would suffice.

The sea held a greater attraction than the voyagers’ “road,” because where land demands that even those in passing take root, the sea represents absolute freedom from all ties. “And now, I feel my great roots unearth, free, and…” The verse that heads the chapter on his liberation from Chichina says it all. All? Che tore up another root in the presence of the old asthmatic Chilean woman. And soon his chest would be stung again when he made friends with a married Chilean couple, communist workers who had been harassed in Baquedano.

The couple, numb with cold, in the desert night, huddling against each other in the desert night, were a living representation of the proletariat in any part of the world.

Like good sons of San Martín,§§ they shared their blankets with them.

It was one of the coldest times in my life, but also one which made me feel a little more brotherly toward this strange, for me at least, human species.

That strangeness, that deep separation and intrepid solitude in which he was still wrapped, is curious. There is nothing lonelier than adventure. Until he was filled with pity for the galley slaves and for the whipped child, Don Quixote was alone, surrounded by strangeness, by the craziness of the world around him. In his Meditations on Quixote, José Ortega y Gasset wrote, as the center of his reflections, “I am myself and my circumstances,” which has usually been understood as the sum or symbiosis of two factors. It may also be understood as a dilemma in which the “I” or “myself” expresses those two factors as separated, distanced, though intensely related. This dilemma appeared in Che’s memoirs of his first “departure,” when he said:

Although the blurred silhouette of the couple was nearly lost in the distance separating us, we could still see the man’s singularly determined face and we remembered his straightforward invitation: “Come, comrades, let’s eat together. I, too, am a tramp,” showing his underlying disdain for the parasitic nature he saw in our aimless traveling.

Whose was this secret disdain: the humble worker’s or Che’s? Or perhaps neither, but that the meeting “in the desert night,” the sharing of the mate, bread, cheese and blankets, caused a spark which lit up a painful separation.

At any rate, they were in Chuquicamata, with the mine and the miner from the south: Cold efficiency and impotent resentment go hand in hand in the big mine, linked in spite of the hatred by a common necessity to live, on the one hand, and to speculate on the other…

An imposing suggestion appeared, and the leap to a kind of idea which would achieve its context, its possible meaning, years later in Cuba:

…we will see whether some day, some miner will take up his pick in pleasure and go and poison his lungs with a conscious joy. They say that’s what it’s like over there, where the red blaze that now lights up the world comes from. So they say. I don’t know.

In fact, in Cuba in 1964, Che would link these ideas with the words of the poet León Felipe (I don’t know if Che was familiar with them when writing the lines above): “No one has yet been able to dig to the rhythm of the sun… no one has cut an ear of corn with love and grace.”

I quote these words because today we could tell that great, desperate poet to come now to Cuba; to see how human beings, after passing through all of the stages of capitalist alienation and after thinking of themselves as beasts of burden harnessed to the yoke of the exploiter, have rediscovered their path and have found their way back to play. Now, in our Cuba, work is acquiring a new meaning and is done with a new joy.***

Yet in March 1952, Che simply wrote, “we will see.” The harsh lessons continued in the chapter “Chuquicamata,” named after the mining town that was “like a scene from a modern drama,” and which he soberly described with a balance of impression, reflection and data. Its greatest lesson was “taught by the graveyards of the mines, containing only a small share of the immense number of people devoured by cave-ins, silica and the hellish climate of the mountain.” In his note of March 22, 1952, or some time later revising his notes, Che concluded: “The biggest effort Chile should make is to shake its uncomfortable Yankee friend from its back, a task that for the moment at least is Herculean.” The name Salvador Allende stops us in our tracks. On the motorcycle, on trucks or in vans, on a ship or in a little Ford; sleeping in police stations, under the stars or in occasional shelters; Che struggling almost constantly with his asthma, the two friends crossed Argentina and Chile. They entered Peru on foot. The Peruvian Indians had a huge impact on them, just as the Mexican Indians had impressed Martí:

These people who watch us walk through the streets of the town are a defeated race. Their stares are tame, almost fearful, and completely indifferent to the outside world. Some give the impression they go on living only because it’s a habit they cannot shake.

They come to the kingdom of defeated stone, Pachamama’s kingdom, Mother Earth, who receives the spat-out “chewed coca leaves instead of stones” with their accompanying “troubles.” The center or navel of the world, where Mama Ocllo dropped her golden wedge into the earth. The place Viracocha chose: Cuzco. And there, in the middle of the baroque procession of Our Lord of the Earthquakes, “a brown Christ,” they find an eternal reminder of the north which can only be seen from South America, its fatal and denouncing antithesis:

Standing over the small frames of the Indians gathered to see the procession pass, the blond head of a North American can occasionally be glimpsed. With his camera and sports shirt, he seems to be (and in fact, actually is) a correspondent from another world…

The cathedral of Cuzco brought out the artist in Che, with such observations as this: “Gold doesn’t have the gentle dignity of silver which becomes more charming as it ages, and so the cathedral seems to be decorated like an old woman with too much makeup.” Of the many churches he visited, he was particularly struck by the lonely, disreputable and “pitiful image of the bell towers of the Church of Belén, toppled by the earthquake, lying like dismembered animals on the hillside.” But his most penetrating judgment of Peruvian colonial baroque is found in the lines of his sharply contrasting description of Lima’s cathedral:

There in Lima, the art is more stylized, with an almost effeminate touch: the cathedral towers are tall and graceful, maybe the most slender of all the cathedrals in the Spanish colonies. The lavishness of the woodwork in Cuzco has been left behind and taken up here in gold. The naves are light and airy, contrasting with those dark, hostile caverns of the Inca city. The paintings are also bright, almost joyous, and of schools more recent than the hermetic mestizos, who painted their saints with a dark and captive fury.

Their visit to Machu Picchu on April 5 served as the subject for a newspaper article that Che published in Panama on December 12, 1953, in which there is a careful gathering of data and historical information, and a didactic intention that was absent from his personal notes.

Something similar occurred in an article entitled “A Glance at the Banks of the Giant of Rivers,” which was also published in Panama, on November 22, 1953, though in this Che placed greater emphasis on experience, describing his journey down the Amazon on a raft. The raft, humorously christened Mambo-Tango — so they wouldn’t be accused of being fanatics about the latter — enabled Che and Alberto, with a lot of hard work and danger, to learn about the harsh reality of the Amazonian Indians.

From the solitary heights of the “enigmatic stone blocks” to the debilitating neglect they witnessed on the banks of the Amazon, it was like traveling through a genetic map of the Americas. Celebrating his 24th birthday in the leper colony of San Pablo, Che spoke, in a style reminiscent of Bolívar and Martí: “We constitute a single mestizo race, which from Mexico to the Magellan Straits bears notable ethnographic similarities. And so, in an attempt to rid myself of the weight of smallminded provincialism, I propose a toast to Peru and to a United Latin America.”

There was no hint of solemnity in these words; rather, pretending his words were merely rhetorical, he spoke with a confidence that placed them outside all convention: “My oratory offering was received with great applause.” He did the same in a letter that he wrote to his mother from Bogotá on July 6, 1952, (included here to complete the description of his Colombian experiences), when he referred once again to his “Pan-American speech,” which won “great applause from the notable, and notably drunk, audience,” and when he commented, with affectionate sarcasm, on Granado’s own words of gratitude: “Alberto, who believes he is Perón’s natural heir, delivered such an impressive, demagogic speech that our well-wishers were convulsed with laughter.” But he spoke in a very different tone of the lepers and their lives, using moderation to try — in vain — to hide his own suffering. Writing about their departure from the San Pablo leper colony, Che said:

That night an assembly of the colony’s patients gave us a farewell serenade, with lots of local songs sung by a blind man. The orchestra was made up of a flute player, a guitarist and an accordion player with almost no fingers, and a “healthy” contingent helping out with a saxophone, a guitar and some percussion. After that came the time for speeches, in which four patients spoke as well as they could, a little awkwardly. One of them froze, unable to go on, until out of desperation he shouted, “Three cheers for the doctors!” Afterwards, Alberto thanked them warmly for their welcome…

Che described the scene in detail in the letter to his mother, (“an accordion player with no fingers on his right hand used little sticks tied to his wrist” and “almost all the others were horribly deformed, due to the nervous form of the disease”), trying unsuccessfully not to sadden her too much, comparing it with a “scene from a horror movie,” but the tearing beauty of that farewell was clear:

The patients cast off and to the sound of a folk tune the human cargo drifted away from shore; the faint light of their lanterns giving the people a ghostly quality.

From his notes on their experiences with the lepers, for whom they surely did much good, not only by treating them but also by playing soccer and talking with them in the spirit of unprejudiced, fraternal, intense humanity — explaining the lepers’ immense gratitude — we can perceive the origins of the budding revolutionary in Che. I emphasize these words: “If there’s anything that will make us seriously dedicate ourselves to leprosy, it will be the affection shown to us by all the sick we’ve met along the way.” Impossible to imagine at the time how serious and deep that dedication would be, understanding “leprosy” to mean all of human misery.

Having read these notes, filled with so many contrasts and teachings, with so much comedy and tragedy, like life itself, and having commented — not exhaustively, but only as suggestions — I conclude with the joyous image of Che arriving in Caracas, wrapped in his traveling blanket, staring around him at the Latin American panorama, “muttering all sorts of verses, lulled by the roar of the truck.”

I’ll leave you with no further commentary, because, in its terrible, unadorned majesty, that exceptional final chapter “A Note in the Margin” neither needs nor tolerates it. In fact, I’m not sure whether this unfathomable “revelation” should be placed at the beginning or the end of these “diaries”; the revelation Che saw “printed in the night sky”; his own fate; waiting for “the great guiding spirit to cleave humanity into two antagonistic halves”; the Great Semí who, in Martí’s view of Our America, would go “astride its condor, spreading the seed of the new America through the romantic nations of the continent and the sorrowful islands of the sea.”††† It is an inexorable chapter that, like a tragic flash of lightning, illuminates for us the “sacred space” in the depths of the soul of one who called himself “this small soldier of the 20th century.” Of one who, in our invincible hope, always takes “to the road” again, shield on his arm and feeling “the ribs of Rocinante”‡‡‡ beneath his heels.

* Simón Bolívar led several armed rebellions, helping to win independence from Spain for much of Latin America. His vision was for a federation of Spanish-speaking South American states.

† The ravine in which Che’s guerrilla unit was ambushed on October 8, 1967, and Che himself taken hostage. He was murdered the following day.

‡ José Martí, Cuban national hero and noted poet, writer, speaker and journalist. Martí founded the Cuban Revolutionary Party in 1892 to fight Spanish rule and oppose U.S. neocolonialism. He launched the 1895 independence war and was killed in battle.

§ José Martí, Obras completas (Complete Works),Havana: Editorial Nacional de Cuba, 1963–73, vol.7, pp.289–90.