The Motorcycle Diaries | |

|---|---|

| Author | Ernesto Guevara |

| Written in | 1950s |

| First published | 1995 |

| Type | Diary |

Contents

Preface by Aleida Guevara

Preface to the first edition by Aleida March

Biography of Ernesto Che Guevara

Brief chronology of Ernesto Che Guevara

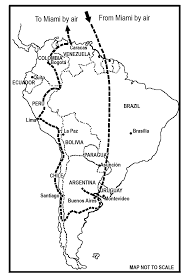

Map and Itinerary of The Motorcycle Diaries

Introduction by Cintio Vitier

The Motorcycle Diaries

So we understand each other

Forewarnings

Discovery of the ocean

...Lovesick pause

Until the last tie is broken

For the flu, bed

San Martin de los Andes

Circular exploration

Dear Mama

On the Seven Lakes Road

An now, I feel my great roots unearth, free and...

Objects of curiosity

The Experts

The difficulties intensify

La Poderosa II's final tour

Firefighters, workers and other matters

La Gioconda's smile

Stowaways

This time, disaster

Chuquicamata

Arid land for miles and miles

The end of Chile

Chjle, a vision from afar

Tarata, the new world

In the dominions of Pachamama

Lake of the sun

Toward the navel of the world

The navel

The land of the Incas

Out Lord of the Earthquakes

Homeland for the victor

Cuzco straight

Huambo

Ever northward

Through the center of Peru

Shattered hopes

The city of the viceroys

Down the Ucayali

Dear Papi

The San Pablo leper colony

Saint Guevara's day

Dear Mama

On the road to Caracas

This strange 20th century

A note in the margin

Preface by Aleida Guevara

When I read these notes for the first time, they were not yet in book form and I did not know the person who had written them. I was much younger then and I identified immediately with this man who had narrated his adventures in such a spontaneous way. Of course, as I continued reading, I began to see more clearly who this person was and I was very glad to be his daughter.

It is not my aim to tell you anything of what you will discover as you read, but I do not doubt that when you have finished the book you will want to go back to enjoy some passages again, either for the beauty they describe or the intensity of the feelings they convey.

There were moments when I literally took over Granado’s place on the motorbike and clung to my dad’s back, journeying with him over the mountains and around the lakes. I admit there were some occasions when I left him to himself, especially at those times when he writes so graphically things I would never talk about myself. When he does, however, he reveals yet again just how honest and unconventional he could be.

To tell you the truth, I should say that the more I read, the more in love I was with the boy my father had been. I do not know if you will share these sentiments with me, but while I was reading, I got to know the young Ernesto better: the Ernesto who left Argentina with his yearning for adventure and his dreams of the great deeds he would perform, and the young man who, as he discovered the reality of our continent, continued to mature as a human being and to develop as a social being.

Slowly we see how his dreams and ambitions changed. He grew increasingly aware of the pain of many others and he allowed it to become a part of himself.

The young man, who makes us smile at the beginning with his absurdities and craziness, becomes before our eyes increasingly sensitive as he tells us about the complex indigenous world of Latin America, the poverty of its people and the exploitation to which they are submitted. In spite of it all, he never loses his sense of humor, which instead becomes finer and more subtle.

My father, “ése, el que fue” (“myself, the man I used to be”), shows us a Latin America that few of us know about, describing its landscapes with words that color each image and reach into our senses, so that we too can see the things his eyes took in.

His prose is fresh. His words allow us to hear sounds we have never heard before, infusing us with the surroundings that struck this romantic being with their beauty and their crudity, yet he never loses his tenderness even as he becomes firmer in his revolutionary longing. His awareness grows that what poor people need is not so much his scientific knowledge as a physician, but rather his strength and persistence in trying to bring about the social change that would enable them to live with the dignity that had been taken from them and trampled on for centuries.

This young adventurer with his thirst for knowledge and his great capacity to love shows us how reality, if properly interpreted, can permeate a human being to the point of changing his or her way of thinking.

Read these notes of his that were written with so much love, eloquence and sincerity, these notes that more than anything else make me feel closer to my father. I hope you enjoy them and that you can join him on his journey.

If you ever have the opportunity to follow his footsteps in reality, you will discover with sadness that many things remain unchanged or are even worse, and this is a challenge for those of us who — like this young man who years later would become Che — are sensitive to the reality that so mistreats the most wretched among us, those of us who have a commitment to helping create a world that is much more just.

I shall leave you now with the man I knew, the man I love intensely for the strength and tenderness he demonstrated in the way he lived.

Enjoy your reading! Ever onward!

Aleida Guevara March

July 2003

Preface to the First Edition

Ernesto Guevara’s travel diaries, transcribed by Che’s Personal Archive in Havana,* recount the trials, vicissitudes and tremendous adventure of a young man’s journey of discovery through Latin America. Ernesto began writing these diaries when, in December 1951, he set off with his friend Alberto Granado on their long-awaited trip from Buenos Aires, down the Atlantic coast of Argentina, across the pampas, through the Andes and into Chile, and from Chile northward to Peru and Colombia and finally to Caracas.

These experiences were later rewritten by Ernesto himself in narrative form, offering the reader a deeper insight into Che’s life, especially at a little known stage, and revealing details of his personality, his cultural background and his narrative skill — the genesis of a style which develops in his later works. The reader can also witness the extraordinary change which takes place in him as he discovers Latin America, gets right to its very heart and develops a growing sense of a Latin American identity, ultimately making him a precursor of the new history of America.

Aleida March

Che’s Personal Archive

Havana, Cuba, 1993

*Now the Che Guevara Studies Center of Havana, Cuba.

Biography of Ernesto "Che" Guevara

One of Time magazine’s “icons of the century,” Ernesto Guevara de la Serna was born in Rosario, Argentina, on June 14, 1928. He made several trips around Latin America during and immediately after his studies at medical school in Buenos Aires, including his 1952 journey with Alberto Granado, on the unreliable Norton motorbike La Poderosa II described in this travel diary.

He was already becoming involved in political activity and living in Guatemala when, in 1954, the democratically elected government of Jacobo Árbenz was overthrown in the CIA-organized military operation. Ernesto escaped to Mexico, profoundly radicalized.

Following up on a contact made in Guatemala, Guevara sought out a group of exiled Cuban revolutionaries in Mexico City. In July 1955, he met Fidel Castro and immediately enlisted in the Cuban guerrilla expedition to overthrow the dictator Fulgencio Batista. The Cubans nicknamed Ernesto “Che,” a popular form of address in Argentina.

On November 25, 1956, Guevara set sail for Cuba aboard the yacht Granma as the doctor to the guerrilla group that began the revolutionary armed struggle in Cuba’s Sierra Maestra mountains. Within several months, he had become the first Rebel Army commander, though he continued treating wounded guerrilla fighters and captured soldiers from Batista’s army.

In September 1958, Guevara played a decisive role in the military defeat of Batista after he and Camilo Cienfuegos led separate guerrilla columns westward from the Sierra Maestra.

After Batista fled on January 1, 1959, Guevara became a key leader of the new revolutionary government, first as head of the Department of Industry of the National Institute of Agrarian Reform, then as president of the National Bank. In February 1961 he became minister of industry. He was also a central leader of the political organization that in 1965 became the Communist Party of Cuba.

Apart from these responsibilities, Guevara represented the Cuban revolutionary government around the world, heading several delegations and speaking at the United Nations and other international forums in Asia, Africa, Latin America and the socialist bloc countries. He earned a reputation as a passionate and articulate spokesperson for Third World peoples, most famously at the Organization of American States (OAS) conference at Punta del Este in Uruguay, where he denounced U.S. President Kennedy’s Alliance for Progress.

As had been his intention since joining the Cuban revolutionary movement, Guevara left Cuba in April 1965, initially to lead a guerrilla mission to support the revolutionary struggle in the Congo. He returned to Cuba secretly in December 1965, to prepare another guerrilla force for Bolivia. Arriving in Bolivia in November 1966, Guevara’s plan was to challenge that country’s military dictatorship and eventually instigate a revolutionary movement that would extend throughout the continent of Latin America. He was wounded and captured by U.S.-trained-and-run Bolivian counter-insurgency troops on October 8, 1967. The following day he was murdered and his body hidden.

Che Guevara’s remains were finally discovered in 1997 and returned to Cuba. A memorial was built at Santa Clara in central Cuba, where he had won a major military battle during the Cuban revolutionary war.

Brief Chronology of Ernesto "Che" Guevara

1928

Ernesto Guevara is born on June 14 in Rosario, Argentina. He is the first child of middle-class parents Ernesto Guevara Lynch and Celia de la Serna.

1932

The Guevara family moves from Buenos Aires to Alta Gracia, a spa town near Córdoba, on account of Ernesto’s chronic asthma. His asthma also prevents him from regular attendance at school until he is nine years old.

1948

Altering his initial plan to study engineering, Ernesto enrolls in medical school at the University of Buenos Aires, while holding a series of part-time jobs, including in an allergy treatment clinic.

1950

Ernesto sets out on a 4,500 kilometer trip around the north of Argentina on a motorized bicycle.

1951-52

In October 1951, Ernesto and his friend Alberto Granado decide on a plan to ride Alberto’s motorbike (La Poderosa II — The Mighty One) to North America. Granado is a biochemist who had specialized in leprology and whose younger brothers had been Ernesto’s school friends. They leave Córdoba in December, heading first to farewell Ernesto’s family in Buenos Aires. The adventures experienced on this trip, written up by Ernesto during and after the journey, comprise this book, published first as Notas de Viaje (Travel Notes or The Motorcycle Diaries).

1953

Ernesto graduates as a doctor and almost immediately embarks on another journey around Latin America which takes in Bolivia, Peru, Ecuador, Panama, Costa Rica and Guatemala, where he meets Antonio (Ñico) López, a young Cuban revolutionary. In Bolivia, he is witness to the Bolivian Revolution. The account of these travels was first published as Otra Vez (in English, Latin America Diaries).

1954

Ernesto’s political views are profoundly radicalized when in Guatemala he sees the overthrow of the democratically elected government of Jacobo Arbenz by U.S.-backed forces. He escapes to Mexico where he contacts the group of Cuban revolutionary exiles. In Mexico, he marries Peruvian Hilda Gadea, with whom he has a daughter, Hildita.

1955

After meeting Fidel Castro, he agrees to join the group being organized to wage guerrilla war against the Batista dictatorship. Now called “Che” by the Cubans — a common nickname for Argentines — in November 1956 he sails as the troop’s doctor on the yacht Granma.

1956-58

Che soon demonstrates outstanding military ability and is promoted to the rank of commander in July 1957. In December 1958, he leads the Rebel Army to a decisive victory over Batista’s forces at Santa Clara in central Cuba.

1959

In February, Che is declared a Cuban citizen in recognition of his contribution to the island’s liberation. He marries Aleida March, with whom he has four children. In October, he is appointed head of the Industrial Department of the Institute of Agrarian Reform and in November becomes President of the National Bank of Cuba. With a gesture of disdain for money, he signs the new banknotes simply as “Che.”

1960

Representing the revolutionary government, Che undertakes an extensive trip to the Soviet Union, the German Democratic Republic, Czechoslovakia, China and North Korea, signing several key trade agreements.

1961

Che is appointed head of the newly established Ministry of Industry. In August, he heads Cuba’s delegation to the Organization of American States (OAS) at Punta del Este, Uruguay, where he denounces U.S. President Kennedy’s Alliance for Progress.

1962

A fusion of Cuban revolutionary organizations takes place and Che is elected to the National Directorate. Che visits the Soviet Union for the second time.

1963

Che travels to Algeria, which has just won independence from France under the government of Ahmed Ben Bella.

1964

Before heading off for an extensive trip around Africa, Che addresses the UN General Assembly in December.

1965

Che leads an international mission to the Congo to support the liberation movement founded by Patrice Lumumba. Responding to mounting speculation about Che’s whereabouts, Fidel Castro reads Che’s farewell letter to the Central Committee of the newly founded Cuban Communist Party. In December, Che returns to Cuba to prepare in secret for a new mission to Bolivia.

1966

In November, Che arrives in Bolivia in disguise.

1967

In April, Che’s “Message to the Tricontinental” is published, calling for the creation of “two, three, many Vietnams.” The same month, part of his guerrilla group becomes separated from the main detachment. On October 8, the remaining 17 guerrillas are ambushed and Che is wounded and captured. The following day he is murdered by Bolivian forces acting under instructions from Washington. His remains are buried in an unmarked grave along with the bodies of several other guerrilla fighters. October 8 is designated the Day of the Heroic Guerrilla in Cuba.

1997

Che’s remains are finally located in Bolivia and returned to Cuba, where they are placed in a memorial at Santa Clara.

Map and Itinerary

Map of the Motorcycle Diaries

Itinerary of the Motorcycle Diaries

ARGENTINA

1951

December Córdoba to Buenos Aires

1952

January 4 Leave Buenos Aires

January 6 Villa Gesell

January 13 Miramar

January 14 Necochea

January 16–21 Bahía Blanca

January 22 En route to Choele Choel

January 25 Choele Choel

January 29 Piedra del Águila

January 31 San Martín de los Andes

February 8 Nahuel Huapí

February 11 San Carlos de Bariloche

CHILE

February 14 Take the Modesta Victoria to Peulla

February 18 Temuco

February 21 Lautaro

February 27 Los Ángeles

March 1 Santiago de Chile

March 7 Valparaíso

March 8–10 Aboard the San Antonio

March 11 Antofagasta

March 12 Baquedano

March 13–15 Chuquicamata

March 20 Iquique (and the Toco, La Rica Aventura and Prosperidad Nitrate Companies)

March 22 Arica

PERU

March 24 Tacna

March 25 Tarata

March 26 Puno

March 27 Sail on Lake Titicaca

March 28 Juliaca

March 30 Sicuani

March 31 – April 3 Cuzco

April 4–5 Machu Picchu

April 6–7 Cuzco

April 11 Abancay

April 13 Huancarama

April 14 Huambo

April 15 Huancarama

April 16–19 Andahuaylas

April 22–24 Ayacucho to Huancallo

April 25–26 La Merced

April 27 Between Oxapampa and San Ramón

April 28 San Ramón

April 30 Tarma

May 1–17 Lima

May 19 Cerro de Pasco

May 24 Pucallpa

May 25–31 Aboard La Cenepa sailing down Río Ucayali, a tributary of the Amazon

June 1–5 Iquitos

June 6–7 Aboard El Cisne sailing to the leper colony of San Pablo

June 8–20 San Pablo

June 21 Aboard the Mambo-Tango raft on the Amazon

COLOMBIA

June 23 – July 1 Leticia

July 2 Leave Leticia by plane

July 2–10 Bogotá

July 12–13 Cúcuta

VENEZUELA

July 14 San Cristóbal

July 16 Between Barquisimeto and Corona

July 17–26 Caracas, where Che and Alberto separate

UNITED STATES

Late July Miami

ARGENTINA

August Che returns to his family in Córdoba

Introduction by Cintio Vitier

If there is one hero in Latin America’s struggle for liberation — stretching from Bolívar’s* time until our own —who has attracted young people from Latin America and from all over the world, that hero is Ernesto Che Guevara. And though since his death he has become a modern myth, he has not yet been stripped of his youthful vitality. To the contrary, his mythic status has only served to heighten his youthfulness which, together with his daring and his purity, seem to constitute the secret essence of his charisma.

Becoming a myth, a symbol of so many scattered and fiercely held hopes, presupposes that such a character possesses a kind of gravity, a certain solemnity. It is good that this is so; historic utopia needs faces to embody it. But we shouldn’t lose sight of the everyday nature of those human beings, who were children, teenagers and young people before they acquired the skills by which to guide us. It is not that I want to bury their exceptional natures in the common or familiar aspects of their lives, but that knowledge of those first, formative stages shows us the starting point for their later trajectories

This is especially true in Che’s case, whose account of this first trip he made with his friend Alberto Granado offers the young at heart such a close and cheerful, serious and at the same time ironic image of the young man, that we can almost glimpse his smile and hear his voice and asthmatic wheeze. He is young, like them, and he filled his whole life with youthfulness and matured his youth without diluting it.

This edition of The Motorcycle Diaries, the notes describing a journey made without hesitation, aboard the noisy motorcycle La Poderosa II (which gave out halfway, but only after transmitting to the adventure a joyous impulse we, too, receive), free as the wind, with the sole purpose of getting to know the world, is dedicated to people whose youth is not merely sequential, but wholehearted and spiritual.

In the first pages, the young man who would become one of the genuine heroes of the 20th century cautions us, “This is not a story of heroic feats.” The word “heroic” rings out above the others, because we cannot read these pages without thinking of Che’s future, an image of him in the Sierra Maestra, an image which reached perfection at Quebrada del Yuro in Bolivia.†

If this youthful adventure had not been prelude to his revolutionary formation, these pages would be different, and we would read them differently, though we cannot imagine how. Simply knowing that they are Che’s — though he wrote them before becoming Che — makes us believe that he had a presentiment regarding the way they should be read. For example:

The person who wrote these notes passed away the moment his feet touched Argentine soil again. The person who reorganizes and polishes them, me, is no longer, at least I’m not the person I once was. All this wandering around “Our America with a capital A” has changed me more than I thought.

These pages are a testimony — a photographic negative, as he also put it — of an experience that changed him, a first “departure” toward the outer world which, like his final departure, was Quixotic in its semi-unconscious style and, as for Quixote, had the same effect on the scope of his consciousness. This was the “spirit of a dreamer” experiencing an awakening.

In principle, and with the perfect logic of the unforeseeable, their journey was at first directed toward North America, as in fact it turned out to be: toward the “photographic negative” of North America that is South American poverty and helplessness, and toward real knowledge of what North America means for us.

“The enormity of our endeavor escaped us in those moments; all we could see was the dust on the road ahead and ourselves on the bike, devouring kilometers in our flight northward.” Wasn’t that “dust on the road,” though without Che realizing it, really the same dust José Martí‡ saw when he traveled from La Guaira to Caracas “in a common little coach”? Wasn’t it the Quixotic dust in which the ghosts of American redemption appeared, “the natural cloud of dust that must rise when our terrible casing of chains falls to the ground”?§ But Martí was coming from the north, and Che was traveling toward himself, catching only glimpses of his destiny, which we glimpse as well through his anecdotes and vignettes.

Comeback, the little dog with “aviator’s impulses” Che presents to us so comically, leaping around the motorcycle from Villa Gesell to Miramar, reappears years later in the Sierra Maestra mountains as a puppy who must be strangled, because of its “hysterical howls” during an unsuccessful ambush laid in the hope of catching [Batista’s notorious army colonel] Sánchez Mosquera. “With one last nervous twitch, the puppy stopped moving. There it lay, sprawled out, its little head spread over the twigs.”** But, at the end of this incident from Episodes of the Revolutionary War, another dog appears lying in the hamlet of Mar Verde:

Félix patted its head, and the dog looked at him. Félix returned the glance, and then he and I exchanged a guilty look. Suddenly everyone fell silent. An imperceptible stirring came over us, as the dog’s meek yet roguish gaze seemed to contain a hint of reproach. There, in our presence, though observing us through the eyes of another dog, was the murdered puppy

It was Comeback who had returned, living up to his name, reminding us also of what Ezequiel Martínez Estrada, our other great Argentine, said about José Martí’s campaign diary:

These emotions, these sensations, cannot be described or expressed in the language of poets and painters, musicians and mystics; they must be… absorbed without reply, as animals do with their contemplative and entranced eyes.††

A comparison of Episodes with The Motorcycle Diaries shows us that, even though more than 10 years had passed, the latter was a literary model for the former. It contains the same moderation; the same candor; the same nimble freshness; exactly the same concept of moments used to provide unity for each brief chapter; and, of course, the same imperturbable steadiness that accepts both happy and tragic events without sharp inhalation or exhalation.

It isn’t literary skill but fidelity to experience and narrative effectiveness that is sought. When both are attained, skill follows naturally, taking its allotted place, neither blinding nor disturbing but making its contribution. Here, with little fumbling or hesitation, Che’s style is already formed. The years would polish it, just as he himself polished his will with the pleasure of an artist, though not that of a wordsmith: a quiet shyness forced him not to dwell too much but to push on with the words toward the poetry of the naked image, which his minimal touch turned into reality. His “I—it-inme” circle opens and closes continually without ever becoming dense, accommodating a style that prefers to remain hidden. The prose on the page sheds light, though does not drag on the imperceptible lightness of the narrative. It flows between description of feeling (in Episodes, “the determined murderer left a trail of burned huts, of sullen sadness…”) and narrative accounts in which he searches for himself (in the Diaries, “Man, the measure of all things, speaks here through my mouth and narrates in my own language that which my eyes have seen”) and sometimes even seems to be watching us.

Che’s colorful prose paints objects as far as his eyes can see and often, if the landscape permits it, with an intimate touch:

The road snakes between the low foothills that sound the beginning of the great cordillera of the Andes, then descends steeply until it reaches an unattractive, miserable town, surrounded in sharp contrast by magnificent, densely wooded mountains.

The episode of the attempt to steal wine, and others in this cheeky tradition, contains precious pearls of diction:

The fact was, we were as broke as ever, retracing in our minds the smiles that had greeted my drunken antics, trying to find some trace of the irony with which we could identify the thief.

A sense of strangeness returns. In the chapter “Circular Exploration”: “As night fell it brought us a thousand strange noises and the sensation of walking into empty space with each step.” In Episodes: “Then, in the middle of the ambush, an eerie moment of silence arose. When we went to gather the dead after the initial shooting, there was no one on the highway…” The imagery is fairly bursting with both the abundance and the silence of the visual world:

The huge figure of a stag dashed like a quick breath across the stream and his body, silver by the light of the rising moon, disappeared into the undergrowth. This tremor of nature cut straight to our hearts. (The Motorcycle Diaries) [Fidel’s] voice and presence in the woods, lit up by the torches, took on moving tones, and you could see that our leader changed the ideas of many people. (Episodes)

Though reference is made to Fidel’s voice and tone, the scene seems silent to us, as if it has been witnessed from afar.

In these travel notes, several Quixotic or Chaplinesque episodes — such as the already cited theft of the wine, the nocturnal pursuit of the two young men “by a furious swarm of dancers,” their enlistment in a corps of Chilean firefighters, the delectable escapade of the melons and their trail over the waves, and the enigma of the impossible photo in a miserable hut on a hill near Caracas — are wrapped in a similar silence.

La Poderosa’s near to last stand is told with cinematographic effect and we seem to be watching it all amid a film-like silence:

I threw on the hand brake which, soldered ineptly, also broke. For some moments, I saw nothing more than the blurred shape of cattle flying past us on each side, while poor Poderosa gathered speed down the steep hill. By an absolute miracle we managed to graze only the leg of the last cow, but in the distance a river was screaming toward us with terrifying efficacy. I veered on to the side of the road and in the blink of an eye the bike mounted the two-meter bank, embedding us between two rocks, but we were unhurt.

These youthful adventures — veined with cheerfulness, humor and frequently self-directed irony — seek the spirit of the landscape rather than merely the scenery. That “spirit” was found in the sudden appearance of the deer: “We walked slowly so as not to disturb the peace of the wild sanctuary with which we were now communing.” Che writes with none of the sarcasm he dedicates to the topic of religion: “Both [of us] assistants waited for Sunday [and the roast] with a kind of religious devotion.” So while being unbelievers, they were able to feel the metaphorical presence of a “sanctuary” in nature, where they were in close rapport with its “spirit” — immediately reminding us of analogous images from the freethinking Martí, such as this from his Simple Verses: “The bishop of Spain seeks / Supports for his shrine. / On wild mountain peaks / The poplars are mine.”‡‡ On March 7, 1952, in Valparaíso, they came face to face with injustice: its victim was an asthmatic old woman, a customer in a small shop by the name of La Gioconda:

The poor thing was in a pitiful state, breathing the acrid smell of concentrated sweat and dirty feet that filled her room, mixed with the dust from a couple of armchairs, the only luxury items in her house. On top of her asthma, she had a heart condition.

After completing a picture of total ruin, and further embittered by the animosity of the sick woman’s family, Che — who felt helpless as a doctor and was approaching the awakening of conscience that would trigger his other, definitive vocation — wrote these memorable words:

It is there, in the final moments, for people whose farthest horizon has always been tomorrow, that one comprehends the profound tragedy circumscribing the life of the proletariat the world over. In those dying eyes there is a submissive appeal for forgiveness and also, often, a desperate plea for consolation which is lost to the void, just as their body will soon be lost in the magnitude of the mystery surrounding us.

Unable to continue their journey any other way, the pair decided to stow away on a ship that would take them to Antofagasta, Chile. At that moment, they — or, at least, Che — did not see things so clearly:

There [looking at the sea, leaning side by side on the railing of the San Antonio], we understood that our vocation, our true vocation, was to move for eternity along the roads and seas of the world. Always curious, looking into everything that came before our eyes, sniffing out each corner but only ever faintly—not setting down roots in any land or staying long enough to see the substratum of things; the outer limits would suffice.

The sea held a greater attraction than the voyagers’ “road,” because where land demands that even those in passing take root, the sea represents absolute freedom from all ties. “And now, I feel my great roots unearth, free, and…” The verse that heads the chapter on his liberation from Chichina says it all. All? Che tore up another root in the presence of the old asthmatic Chilean woman. And soon his chest would be stung again when he made friends with a married Chilean couple, communist workers who had been harassed in Baquedano.

The couple, numb with cold, in the desert night, huddling against each other in the desert night, were a living representation of the proletariat in any part of the world.

Like good sons of San Martín,§§ they shared their blankets with them.

It was one of the coldest times in my life, but also one which made me feel a little more brotherly toward this strange, for me at least, human species.

That strangeness, that deep separation and intrepid solitude in which he was still wrapped, is curious. There is nothing lonelier than adventure. Until he was filled with pity for the galley slaves and for the whipped child, Don Quixote was alone, surrounded by strangeness, by the craziness of the world around him. In his Meditations on Quixote, José Ortega y Gasset wrote, as the center of his reflections, “I am myself and my circumstances,” which has usually been understood as the sum or symbiosis of two factors. It may also be understood as a dilemma in which the “I” or “myself” expresses those two factors as separated, distanced, though intensely related. This dilemma appeared in Che’s memoirs of his first “departure,” when he said:

Although the blurred silhouette of the couple was nearly lost in the distance separating us, we could still see the man’s singularly determined face and we remembered his straightforward invitation: “Come, comrades, let’s eat together. I, too, am a tramp,” showing his underlying disdain for the parasitic nature he saw in our aimless traveling.

Whose was this secret disdain: the humble worker’s or Che’s? Or perhaps neither, but that the meeting “in the desert night,” the sharing of the mate, bread, cheese and blankets, caused a spark which lit up a painful separation.

At any rate, they were in Chuquicamata, with the mine and the miner from the south: Cold efficiency and impotent resentment go hand in hand in the big mine, linked in spite of the hatred by a common necessity to live, on the one hand, and to speculate on the other…

An imposing suggestion appeared, and the leap to a kind of idea which would achieve its context, its possible meaning, years later in Cuba:

…we will see whether some day, some miner will take up his pick in pleasure and go and poison his lungs with a conscious joy. They say that’s what it’s like over there, where the red blaze that now lights up the world comes from. So they say. I don’t know.

In fact, in Cuba in 1964, Che would link these ideas with the words of the poet León Felipe (I don’t know if Che was familiar with them when writing the lines above): “No one has yet been able to dig to the rhythm of the sun… no one has cut an ear of corn with love and grace.”

I quote these words because today we could tell that great, desperate poet to come now to Cuba; to see how human beings, after passing through all of the stages of capitalist alienation and after thinking of themselves as beasts of burden harnessed to the yoke of the exploiter, have rediscovered their path and have found their way back to play. Now, in our Cuba, work is acquiring a new meaning and is done with a new joy.***

Yet in March 1952, Che simply wrote, “we will see.” The harsh lessons continued in the chapter “Chuquicamata,” named after the mining town that was “like a scene from a modern drama,” and which he soberly described with a balance of impression, reflection and data. Its greatest lesson was “taught by the graveyards of the mines, containing only a small share of the immense number of people devoured by cave-ins, silica and the hellish climate of the mountain.” In his note of March 22, 1952, or some time later revising his notes, Che concluded: “The biggest effort Chile should make is to shake its uncomfortable Yankee friend from its back, a task that for the moment at least is Herculean.” The name Salvador Allende stops us in our tracks. On the motorcycle, on trucks or in vans, on a ship or in a little Ford; sleeping in police stations, under the stars or in occasional shelters; Che struggling almost constantly with his asthma, the two friends crossed Argentina and Chile. They entered Peru on foot. The Peruvian Indians had a huge impact on them, just as the Mexican Indians had impressed Martí:

These people who watch us walk through the streets of the town are a defeated race. Their stares are tame, almost fearful, and completely indifferent to the outside world. Some give the impression they go on living only because it’s a habit they cannot shake.

They come to the kingdom of defeated stone, Pachamama’s kingdom, Mother Earth, who receives the spat-out “chewed coca leaves instead of stones” with their accompanying “troubles.” The center or navel of the world, where Mama Ocllo dropped her golden wedge into the earth. The place Viracocha chose: Cuzco. And there, in the middle of the baroque procession of Our Lord of the Earthquakes, “a brown Christ,” they find an eternal reminder of the north which can only be seen from South America, its fatal and denouncing antithesis:

Standing over the small frames of the Indians gathered to see the procession pass, the blond head of a North American can occasionally be glimpsed. With his camera and sports shirt, he seems to be (and in fact, actually is) a correspondent from another world…

The cathedral of Cuzco brought out the artist in Che, with such observations as this: “Gold doesn’t have the gentle dignity of silver which becomes more charming as it ages, and so the cathedral seems to be decorated like an old woman with too much makeup.” Of the many churches he visited, he was particularly struck by the lonely, disreputable and “pitiful image of the bell towers of the Church of Belén, toppled by the earthquake, lying like dismembered animals on the hillside.” But his most penetrating judgment of Peruvian colonial baroque is found in the lines of his sharply contrasting description of Lima’s cathedral:

There in Lima, the art is more stylized, with an almost effeminate touch: the cathedral towers are tall and graceful, maybe the most slender of all the cathedrals in the Spanish colonies. The lavishness of the woodwork in Cuzco has been left behind and taken up here in gold. The naves are light and airy, contrasting with those dark, hostile caverns of the Inca city. The paintings are also bright, almost joyous, and of schools more recent than the hermetic mestizos, who painted their saints with a dark and captive fury.

Their visit to Machu Picchu on April 5 served as the subject for a newspaper article that Che published in Panama on December 12, 1953, in which there is a careful gathering of data and historical information, and a didactic intention that was absent from his personal notes.

Something similar occurred in an article entitled “A Glance at the Banks of the Giant of Rivers,” which was also published in Panama, on November 22, 1953, though in this Che placed greater emphasis on experience, describing his journey down the Amazon on a raft. The raft, humorously christened Mambo-Tango — so they wouldn’t be accused of being fanatics about the latter — enabled Che and Alberto, with a lot of hard work and danger, to learn about the harsh reality of the Amazonian Indians.

From the solitary heights of the “enigmatic stone blocks” to the debilitating neglect they witnessed on the banks of the Amazon, it was like traveling through a genetic map of the Americas. Celebrating his 24th birthday in the leper colony of San Pablo, Che spoke, in a style reminiscent of Bolívar and Martí: “We constitute a single mestizo race, which from Mexico to the Magellan Straits bears notable ethnographic similarities. And so, in an attempt to rid myself of the weight of smallminded provincialism, I propose a toast to Peru and to a United Latin America.”

There was no hint of solemnity in these words; rather, pretending his words were merely rhetorical, he spoke with a confidence that placed them outside all convention: “My oratory offering was received with great applause.” He did the same in a letter that he wrote to his mother from Bogotá on July 6, 1952, (included here to complete the description of his Colombian experiences), when he referred once again to his “Pan-American speech,” which won “great applause from the notable, and notably drunk, audience,” and when he commented, with affectionate sarcasm, on Granado’s own words of gratitude: “Alberto, who believes he is Perón’s natural heir, delivered such an impressive, demagogic speech that our well-wishers were convulsed with laughter.” But he spoke in a very different tone of the lepers and their lives, using moderation to try — in vain — to hide his own suffering. Writing about their departure from the San Pablo leper colony, Che said:

That night an assembly of the colony’s patients gave us a farewell serenade, with lots of local songs sung by a blind man. The orchestra was made up of a flute player, a guitarist and an accordion player with almost no fingers, and a “healthy” contingent helping out with a saxophone, a guitar and some percussion. After that came the time for speeches, in which four patients spoke as well as they could, a little awkwardly. One of them froze, unable to go on, until out of desperation he shouted, “Three cheers for the doctors!” Afterwards, Alberto thanked them warmly for their welcome…

Che described the scene in detail in the letter to his mother, (“an accordion player with no fingers on his right hand used little sticks tied to his wrist” and “almost all the others were horribly deformed, due to the nervous form of the disease”), trying unsuccessfully not to sadden her too much, comparing it with a “scene from a horror movie,” but the tearing beauty of that farewell was clear:

The patients cast off and to the sound of a folk tune the human cargo drifted away from shore; the faint light of their lanterns giving the people a ghostly quality.

From his notes on their experiences with the lepers, for whom they surely did much good, not only by treating them but also by playing soccer and talking with them in the spirit of unprejudiced, fraternal, intense humanity — explaining the lepers’ immense gratitude — we can perceive the origins of the budding revolutionary in Che. I emphasize these words: “If there’s anything that will make us seriously dedicate ourselves to leprosy, it will be the affection shown to us by all the sick we’ve met along the way.” Impossible to imagine at the time how serious and deep that dedication would be, understanding “leprosy” to mean all of human misery.

Having read these notes, filled with so many contrasts and teachings, with so much comedy and tragedy, like life itself, and having commented — not exhaustively, but only as suggestions — I conclude with the joyous image of Che arriving in Caracas, wrapped in his traveling blanket, staring around him at the Latin American panorama, “muttering all sorts of verses, lulled by the roar of the truck.”

I’ll leave you with no further commentary, because, in its terrible, unadorned majesty, that exceptional final chapter “A Note in the Margin” neither needs nor tolerates it. In fact, I’m not sure whether this unfathomable “revelation” should be placed at the beginning or the end of these “diaries”; the revelation Che saw “printed in the night sky”; his own fate; waiting for “the great guiding spirit to cleave humanity into two antagonistic halves”; the Great Semí who, in Martí’s view of Our America, would go “astride its condor, spreading the seed of the new America through the romantic nations of the continent and the sorrowful islands of the sea.”††† It is an inexorable chapter that, like a tragic flash of lightning, illuminates for us the “sacred space” in the depths of the soul of one who called himself “this small soldier of the 20th century.” Of one who, in our invincible hope, always takes “to the road” again, shield on his arm and feeling “the ribs of Rocinante”‡‡‡ beneath his heels.

* Simón Bolívar led several armed rebellions, helping to win independence from Spain for much of Latin America. His vision was for a federation of Spanish-speaking South American states.

† The ravine in which Che’s guerrilla unit was ambushed on October 8, 1967, and Che himself taken hostage. He was murdered the following day.

‡ José Martí, Cuban national hero and noted poet, writer, speaker and journalist. Martí founded the Cuban Revolutionary Party in 1892 to fight Spanish rule and oppose U.S. neocolonialism. He launched the 1895 independence war and was killed in battle.

§ José Martí, Obras completas (Complete Works),Havana: Editorial Nacional de Cuba, 1963–73, vol.7, pp.289–90.

** From Ernesto Che Guevara, Episodes of the Revolutionary War, forthcoming from Ocean Press, 2004. Also in Ernesto Che Guevara, Che Guevara Reader, Ocean Press, 2003, p.37.

†† Ezequiel Martínez Estrada, Martí revolucionario (Martí the Revolutionary), Havana: Casa de las Américas, 1967, p.414, no.184.

‡‡ José Martí, Op. cit., vol.16, p.68.

§§ José de San Martín, Argentine national hero who played a major role in winning independence from Spain for Argentina, Chile and Peru.

*** Ernesto Che Guevara, Obras, 1957–67 (Works, 1957–67),Havana: Casa de las Américas, 1970, vol.II, p.333.

††† José Martí, José Martí Reader, Ocean Press, 1999, p.120.

‡‡‡ .Che Guevara Reader, p.384.

Entendámonos/So we understand each other

This is not a story of heroic feats, or merely the narrative of a cynic; at least I do not mean it to be. It is a glimpse of two lives running parallel for a time, with similar hopes and convergent dreams.

In nine months of a man’s life he can think a lot of things, from the loftiest meditations on philosophy to the most desperate longing for a bowl of soup — in total accord with the state of his stomach. And if, at the same time, he’s somewhat of an adventurer, he might live through episodes of interest to other people and his haphazard record might read something like these notes.

And so, the coin was thrown in the air, turning many times, landing sometimes heads and other times tails. Man, the measure of all things, speaks here through my mouth and narrates in my own language that which my eyes have seen. It is likely that out of 10 possible heads I have seen only one true tail, or vice versa. In fact it’s probable, and there are no excuses, for these lips can only describe what these eyes actually see. Is it that our whole vision was never quite complete, that it was too transient or not always well-informed? Were we too uncompromising in our judgments? Okay, but this is how the typewriter interpreted those fleeting impulses raising my fingers to the keys, and those impulses have now died. Moreover, no one can be held responsible for them.

The person who wrote these notes passed away the moment his feet touched Argentine soil again. The person who reorganizes and polishes them, me, is no longer, at least I am not the person I once was. All this wandering around “Our America with a capital A” has changed me more than I thought.

In any photographic manual you’ll come across the strikingly clear image of a landscape, apparently taken by night, in the light of a full moon. The secret behind this magical vision of “darkness at noon” is usually revealed in the accompanying text. Readers of this book will not be well versed about the sensitivity of my retina — I can hardly sense it myself. So they will not be able to check what is said against a photographic plate to discover at precisely what time each of my “pictures” was taken. What this means is that if I present you with an image and say, for instance, that it was taken at night, you can either believe me, or not; it matters little to me, since if you don’t happen to know the scene I’ve “photographed” in my notes, it will be hard for you to find an alternative to the truth I’m about to tell. But I’ll leave you now, with myself, the man I used to be…

Pródromos/Forewarnings

It was a morning in October. Taking advantage of the holiday on the 17th I had gone to Córdoba.* We were at Alberto Granado’s place under the vine, drinking sweet mate† and commenting on recent events in this “bitch of a life,” tinkering with La Poderosa II.‡ Alberto was lamenting the fact that he had to quit his job at the leper colony in San Francisco del Chañar and about how poor his pay was now at the Español Hospital. I had also quit my job, but unlike Alberto I was very happy to leave. I was feeling uneasy, more than anything because having the spirit of a dreamer I was particularly jaded with medical school, hospitals and exams.

Along the roads of our daydream we reached remote countries, navigated tropical seas and traveled all through Asia. And suddenly, slipping in as if part of our fantasy, the question arose:

“Why don’t we go to North America?”

“North America? But how?”

“On La Poderosa, man.”

The trip was decided just like that, and it never erred from the basic principle laid down in that moment: improvisation. Alberto’s brothers joined us in a round of mate as we sealed our pact never to give up until we had realized our dream. So began the monotonous business of chasing visas, certificates and documents, that is to say, of overcoming the many hurdles modern nations erect in the paths of would-be travelers. To save face, just in case, we decided to say we were going to Chile.

My most important mission before leaving was to take exams in as many subjects as possible; Alberto’s to prepare the bike for the long journey, and to study and plan our route. The enormity of our endeavor escaped us in those moments; all we could see was the dust on the road ahead and ourselves on the bike, devouring kilometers in our flight northward.

* At the time a national holiday to commemorate Juan Perón’s 1945 release from prison. General Perón was president of Argentina from 1946 to 1955 and from 1973 until his death in 1974.

† The Argentine national drink, a tea-like beverage made from the herb mate.

‡ Granado’s Norton 500 motorcycle, literally “The Mighty One."

El descubrimiento del océano/Discovery of the ocean

The full moon is silhouetted against the sea, smothering the waves with silver reflections. Sitting on a dune, we watch the continuous ebb and flow, each with our own thoughts. For me, the sea has always been a confidant, a friend absorbing all it is told and never revealing those secrets; always giving the best advice — its meaningful noises can be interpreted any way you choose. For Alberto, it is a new, strangely perturbing sight, and the intensity with which his eyes follow every wave building, swelling, then dying on the beach, reflects his amazement. Nearing 30, Alberto is seeing the Atlantic for the first time and is overwhelmed by this discovery that signifies an infinite number of paths to all ends of the earth. The fresh wind fills the senses with the power and mood of the sea; everything is transformed by its touch; even Comeback* gazes, his odd little nose aloft, at the silver ribbons unrolling before him several times a minute.

Comeback is both a symbol and a survivor: a symbol of the union demanding my return; a survivor of his own bad luck — two falls from the bike (in one of which he and his bag flew off the back), his persistent diarrhoea and even getting trampled by a horse.

We’re in Villa Gesell, north of Mar del Plata, enjoying my uncle’s hospitality in his home and reliving our first 1,200 kilometers — apparently the easiest, though they’ve already given us a healthy respect for distances. We have no idea whether or not we’ll get there, but we do know the going will be hard — at least that’s the impression we have at this stage. Alberto laughs at his minutely detailed plans for the trip, according to which we should be nearing the end when in reality we have only just begun.

We left Gesell stocked up on vegetables and tinned meat “donated” by my uncle. He asked us to send him a telegram from Bariloche — if we get there — so that with the number of the telegram he could buy a corresponding lottery ticket, which seemed a little optimistic to us. On cue, others taunted that the bike would be a good excuse to go jogging, etc., and though we have a firm resolve to prove them wrong, a natural apprehension keeps us from declaring our confidence in the journey’s success.

Along the coast road Comeback maintains his aviator’s impulses, emerging unscathed from yet another head-on collision. The motorbike is very hard to control, with extra weight on a rack behind the center of gravity tending to lift the front wheel, and the slightest lapse in concentration sends us flying. We stop at a butcher store and buy some meat to grill and milk for the dog, who won’t even try it. I begin to worry more about the little animal’s health than the money I’d forked out to pay for the milk. The meat turns out to be horse. It’s unbearably sweet and we can’t eat it. Fed up, I toss a piece away and amazingly, the dog wolfs it down in no time. I throw him another piece and the same thing happens. His regime of milk is lifted. In the middle of the uproar caused by Comeback’s admirers I enter, here in Miramar, a…

*The English nickname Ernesto has given to the little dog he’s taking to Chichina, his girlfriend who is holidaying in Miramar.

...Paréntesis amoroso/...Lovesick pause

The intention of this diary is not really to recount those days in Miramar where Comeback found a new home, with one resident in particular to whom Comeback’s name was directed. Our journey was suspended in that haven of indecision, subordinate to the words that give consent and create bonds.

Alberto saw the danger and was already imagining himself alone on the roads of America, though he never raised his voice. The struggle was between she and I. For a moment as I left, victorious, or so I thought, Otero Silva’s lines rang in my ears:

I heard splashing on the boat

her bare feet

And sensed in our faces

the hungry dusk

My heart swaying between her

and the street, the road

I don’t know where I found the strength

to free myself from her eyes

to slip from her arms

She stayed, crying through rain and glass

clouded with grief and tears

She stayed, unable to cry

Wait! I will come

walking with you.*

Yet afterwards I doubted whether driftwood has the right to say, “I win,” when the tide throws it on to the beach it seeks. But that was later, and is of no interest to the present. The two days I’d planned stretched like elastic into eight and with the bittersweet taste of goodbye mingling with my inveterate bad breath I finally felt myself lifted definitively away on the winds of adventure toward worlds I envisaged would be stranger than they were, into situations I imagined would be much more normal than they turned out to be.

I remember the day my friend the sea came to my defense — taking me from the limbo I was cursed with. The beach was deserted and a cold onshore wind was blowing. My head rested in the lap tying me to this land, lulled by everything around. The entire universe drifted rhythmically by, obeying the impulses of my inner voice. Suddenly, a stronger gust of wind brought a different sea voice and I lifted my head in surprise, yet it seemed to be nothing, a false alarm. I lay back, returning once again in my dreams to the caressing lap. And then, for the last time, I heard the ocean’s warning. Its vast and jarring rhythm hammered at the fortress within me and threatened its imposing serenity.

We became cold and left the beach, fleeing the disturbing presence which refused to leave me alone. The sea danced on the small stretch of beach, indifferent to its own eternal law and spawning its own note of caution, its warning. But a man in love (though Alberto used a more outrageous, less refined word) is in no condition to listen to such a call from nature; in the enormous belly of a Buick the bourgeois side of my universe was still under construction.

The first commandment for every good explorer is that an expedition has two points: the point of departure and the point of arrival. If your intention is to make the second theoretical point coincide with the actual point of arrival, don’t think about the means — because the journey is a virtual space that finishes when it finishes, and there are as many means as there are different ways of “finishing.” That is to say, the means are endless.

"I remembered Alberto’s suggestion: “The bracelet, or you’re not who you think you are.”

Chichina’s hands disappeared into the hollow made by mine.

“Chichina, that bracelet… Can I take it to guide me and remind me of you?”

The poor girl! I know the gold didn’t matter, despite what they say; her fingers as they held the bracelet were merely weighing up the love that made me ask for it. That is, at least, what I honestly think. Alberto says (with a certain mischievousness, it seems to me), that you don’t need particularly sensitive fingers to weigh up the full 29 carats of my love.

* Miguel Otero Silva, left-wing Venezuelan poet and novelist, born in 1908.

Hasta romper el ultimo vínculo/Until the last tie is broken

We left, stopping next in Necochea where an old university friend of Alberto’s had his practise. We covered the distance easily in a morning, arriving just in time for a steak lunch, receiving a genial welcome from the friend and a not so genial welcome from his wife who spotted the danger in our resolutely bohemian ways.

“You have only one year left before you qualify as a doctor and yet you’re going away? You have no idea when you’ll be back? But why?”

We couldn’t give precise answers to her desperate questions and this horrified her. She was courteous with us but her hostility was clear, despite the fact that she knew (at least I think she knew) ultimate victory was hers — her husband was beyond our “redemption.”

In Mar del Plata we had visited a doctor friend of Alberto’s who had joined the [Peronist] party, with all its consequent privileges. This doctor in Necochea remained faithful to his own — the Radicals — yet we, however, were as remote from one as from the other. Support for the Radicals was never a tenable political position for me and was also losing its significance for Alberto, who had been quite close at one time with some of the leaders he respected.

When we climbed back on to the bike again, after thanking the couple for our three days of the good life, we continued on to Bahía Blanca, feeling a little more alone but a good deal more free. Friends were also expecting us there, my friends this time, and they too offered us warm and friendly hospitality. Several days passed us by in this southern port, as we fixed the bike and wandered aimlessly around the city. These were the last days in which we did not have to think about money. Afterwards, a rigid diet of meat, polenta and bread would have to be followed strictly to stretch our meager finances. The taste of bread was now tinged with warning: “I won’t be so easy to come by soon, old man,” and we swallowed it with all the more enthusiasm. We wanted, like camels, to build our reserves for the journey that lay ahead.

The night before our departure I came down with a cough and quite a high temperature, and consequently we were a day late leaving Bahía Blanca. Finally, at three in the afternoon, we left under a blazing sun that had become even hotter by the time we reached the sand dunes around Médanos. The bike, with its badly distributed weight, kept bounding out of control, the wheels constantly spinning over. Alberto fought a painful battle with the sand and insists he won. The only certainty is that we found ourselves resting comfortably in the sand six times before we finally made it out on to the flat. We did, nevertheless, get out, and this is my compañero’s main argument for claiming victory over Médanos.

From here I took over the controls, accelerating to make up for precious lost time. A fine sand covered part of a bend and — boom: the worst crash of the whole trip. Alberto emerged unscathed but my foot was trapped and scorched by the cylinder, leaving a disagreeable memento which lasted a long time because the wound wouldn’t heal.

A heavy downpour forced us to seek shelter at a ranch, but to reach it we had to get 300 meters up a muddy track and we went flying twice more. Their welcome was magnificent but the sum total of our first experience on unsealed roads was alarming: nine crashes in a single day. On camp beds, the only beds we’d know from now on, and lying beside La Poderosa, our snail-like dwelling, we still looked into the future with impatient joy. We seemed to breathe more freely, a lighter air, an air of adventure. Distant countries, heroic deeds and beautiful women spun around and around in our turbulent imaginations.

My tired eyes refused to sleep and in them a pair of green spots swirled, representing the world I had left for dead behind me and mocking the so-called liberation I sought. They harnessed their image to my extraordinary flight across the lands and seas of the world.

Para las gripes, cama/For the flu, bed

The bike exhaled with boredom along the long accident-free road and we exhaled with fatigue. Driving on a gravel-covered road had transformed a pleasant jaunt into a heavy job. By nightfall, after an entire day of alternating turns at the controls, we were left with more desire to sleep than to continue with the effort to reach Choele Choel, a largish town where we had a chance at free lodging. So we stopped in Benjamín Zorrilla, settling down comfortably in a room at the railroad station. We slept, dead to the world.

We woke early the next morning, but when I went to collect water for our mate a weird sensation darted through my body, followed by a long shiver. Ten minutes later I was shaking uncontrollably like someone possessed. My quinine tablets made no difference, my head was like a drum hammering out strange rhythms, bizarre colors shifted shapelessly across the walls and some desperate heaving produced a green vomit. I spent the whole day like this, unable to eat, until by the evening I felt well enough to climb on the bike and, sleeping on Alberto’s shoulder, we reached Choele Choel. There we visited Dr. Barrera, director of the little hospital and a member of parliament. He received us amiably, giving us a room to sleep in. He prescribed a course of penicillin and within four hours my temperature had lowered, but whenever we talked about leaving the doctor shook his head and said, “For the flu: bed.” (This was his diagnosis, for want of a better one.) So we spent several days there, being cared for royally

Alberto photographed me in my hospital gear. I made an impressive spectacle: gaunt, flushed, enormous eyes and a ridiculous beard whose shape didn’t change much in all the months I wore it. It’s a pity the photograph wasn’t a good one; it was an acknowledgment of our changed circumstances and of the horizons we were seeking, free at last from “civilization.”

One morning the doctor didn’t shake his head in his usual way. That was enough. Within the hour we were gone, heading west toward our next destination — the lakes. The bike struggled, showing signs it was feeling the strain, especially in the bodywork which we constantly had to fix with Alberto’s favored spare part — wire. He picked up this quote from somewhere, I don’t know where, attributing it to Oscar Gálvez:* “When a piece of wire can replace a screw, give me the wire, it’s safer.” Our hands and our pants were unequivocal proof that we were with Gálvez, at least on the question of wire.

It was already night, yet we were trying to reach human habitation; we had no headlight and spending the night in the open didn’t seem much like a pleasant idea. We were moving slowly, using a torch, when a strange noise rang out from the bike that we couldn’t identify. The torch didn’t give out enough light to find the cause and we had no choice but to camp where we were. We settled down as best we could, erecting our tent and crawling into it, hoping to suffocate our hunger and thirst (for there was no water nearby and we had no meat) with some exhausted sleep. In no time, however, the light evening breeze became a violent wind, uprooting our tent and exposing us to the elements and the worsening cold. We had to tie the bike to a telephone pole and, throwing the tent over the bike for protection, we lay down behind it. The near hurricane prevented us from using our camp beds. In no way was it an enjoyable night, but sleep finally won out over the cold, the wind and everything else, and we woke at nine in the morning with the sun high above our heads.

By the light of day, we discovered that the infamous noise had been the front part of the bike frame breaking. We now had to fix it as best we could and find a town where we could weld the broken bar. Our friend, wire, solved the problem provisionally. We packed up and set off not knowing exactly how far we were from nearest habitation. Our surprise was great when, coming out of only the second bend, we saw a house. They received us very well, appeasing our hunger with exquisite roast lamb. From there we walked 20 kilometers to a place called Piedra del Águila where we were able to weld the part, but by then it was so late we decided to spend the night in the mechanic’s house.

Except for a couple of minor spills that didn’t do the bike too much damage, we continued calmly on toward San Martín de los Andes. We were almost there and I was driving when we took our first real fall in the south [of Argentina] on a beautiful gravel bend, by a little bubbling stream. This time La Poderosa’s bodywork was damaged enough to force us to stop and, worst of all, we found we had what we most dreaded: a punctured back tire. In order to mend it, we had to take off all the packs, undo the wire “securing” the rack, then struggle with the wheel cover which defied our pathetic crowbar. Changing the flat (lazily, I admit) lost us two hours. Late in the afternoon we stopped at a ranch whose owners, very welcoming Germans, had by rare coincidence put up an uncle of mine in the past, an inveterate old traveler whose example I was now emulating. They let us fish in the river flowing through the ranch. Alberto cast his line, and before he knew what was happening, he had jumping on the end of his hook an iridescent form glinting in the sunlight. It was a rainbow trout, a beautiful, tasty fish (even more so when baked and seasoned by our hunger). I prepared the fish while Alberto, enthusiastic from this first victory, cast his line again and again. Despite hours of trying he didn’t get a single bite. By then it was dark and we had to spend the night in the farm laborers’ kitchen.

At five in the morning the huge stove occupying the middle of this kind of kitchen was lit and the whole place filled with smoke. The farm laborers passed round their bitter mate and cast aspersions on our own “mate for girls,” as they describe sweet mate in those parts. In general they didn’t try to communicate with us, as is typical of the subjugated Araucanian race who maintain a deep suspicion of the white man who in the past has brought them so much misfortune and now continues to exploit them. They answered our questions about the land and their work by shrugging their shoulders and saying “don’t know” or “maybe,” quickly ending the conversation.

We were given the chance to stuff ourselves with cherries, so much so that by the time we were to move on to the plums I’d had enough and had to lie down to digest it all. Alberto ate some so as not to seem rude. Up the trees we ate avidly, as if we were racing each other to finish. One of the owner’s sons looked on with a certain mistrust at these “doctors,” disgustingly dressed and obviously famished, but he kept his mouth shut and let us eat to our idealistic hearts’ content. It got to the point where we had to walk slowly to avoid stepping on our own stomachs.

We mended the kick-start and other minor problems and set off again for San Martín de los Andes, where we arrived just before dark.

* A champion Argentine rally driver.

San Martín de los Andes/San Martín of the Andes

The road snakes between the low foothills that sound the beginning of the great cordillera of the Andes, then descends steeply until it reaches an unattractive, miserable town, surrounded in sharp contrast by magnificent, densely wooded mountains. San Martín lies on the yellow-green slopes that melt into the blue depths of Lake Lacar, a narrow tongue of water 35 meters wide and 500 kilometers long. The day it was “discovered” as a tourist haven the town’s climate and transport difficulties were solved and its subsistence secured.

Our first attack on the local clinic completely failed but we were told to try the same tactic at the National Parks’ offices. The superintendent of the park allowed us to stay in one of the tool sheds. The nightwatchman arrived, a huge, fat man weighing 140 kilos with a face as hard as nails, but he treated us very amiably, granting us permission to cook in his hut. That first night passed perfectly. We slept in the shed, content and warm on straw — certainly necessary in those parts where the nights are particularly cold.

We bought some beef and set off to walk along the shores of the lake. In the shade of the immense trees, where the wilderness had arrested the advance of civilization, we made plans to build a laboratory in this place, when we finished our trip. We imagined great windows that would take in the whole lake, winter blanketing the ground in white; the dinghy we would use to travel from one side to the other; catching fish from a little boat; everlasting excursions into the almost virgin forest.

Although often on our travels we longed to stay in the formidable places we visited, only the Amazon jungle called out to that sedentary part of ourselves as strongly as did this place.

I now know, by an almost fatalistic conformity with the facts, that my destiny is to travel, or perhaps it’s better to say that traveling is our destiny, because Alberto feels the same. Still, there are moments when I think with profound longing of those wonderful areas in our south. Perhaps one day, tired of circling the world, I’ll return to Argentina and settle in the Andean lakes, if not indefinitely then at least for a pause while I shift from one understanding of the world to another.

At dusk we started back and it was dark before we arrived. We were pleasantly surprised to find that Don Pedro Olate, the night-watchman, had prepared a wonderful barbecue to treat us. We bought wine to return the gesture and ate like lions, just for a change. We were discussing how tasty the meat was and how soon we wouldn’t be eating as extravagantly as we had done in Argentina, when Don Pedro told us he’d been asked to organize a barbecue for the drivers of a motor race taking place on the local track that coming Sunday. He wanted two helpers and offered us the job. “Mind that I can’t pay you, but you can stock up on meat for later.”

It seemed like a good idea and we accepted the jobs of first and second assistants to the “Granddaddy of the Southern Argentine Barbecue.”

Both assistants waited for Sunday with a kind of religious enthusiasm. At six in the morning on the day, we started our first job — loading wood on to a truck and taking it to the barbecue site — and we didn’t stop work until 11 a.m. when the distinctive signal was given and everyone threw themselves voraciously on to the tasty ribs.

A very strange person was giving orders whom I addressed with the utmost respect as “Señora” any time I said a word, until one of my fellow workers said: “Hey kid, che, don’t push Don Pendón too far, he’ll get angry.”

“Who’s Don Pendón?” I asked, with the kind of gesture some uncultured kid would give. The answer, that Don Pendón was the Señora, left me cold, but not for long.

As always at barbecues, there was far too much meat for everyone, so we were given carte blanche to pursue our vocation as camels. We executed, furthermore, a carefully calculated plan. I pretended to get drunker and drunker and, with every apparent attack of nausea, I staggered off to the stream, a bottle of red wine hidden inside my leather jacket. After five attacks of this type we had the same number of liters of wine stored beneath the fronds of a willow, keeping cool in the water. When everything was over and the moment came to pack up the truck and return to town, I kept up my part, working reluctantly and bickering constantly with Don Pendón. To finish my performance I lay down flat on my back in the grass, utterly unable to take another step. Alberto, acting like a true friend, apologized for my behavior to the boss and stayed behind to look after me as the truck left. When the noise of the engine faded in the distance we jumped up and raced off like colts to the wine that would guarantee us several days of kingly consumption.

Alberto made it first and threw himself under the willow: his face was straight out of a comic film. Not a single bottle remained. Either my drunken state hadn’t fooled anyone, or someone had seen me sneak off with the wine. The fact was, we were as broke as ever, retracing in our minds the smiles that had greeted my drunken antics, trying to find some trace of the irony with which we could identify the thief. To no avail. Lugging the chunk of bread and cheese we’d received and a few kilos of meat for the night, we had to walk back to town. We were well-fed and well-watered, but with our tails between our legs, not so much for the wine but for the fools they’d made of us. Words cannot describe it.

The following day was rainy and cold and we thought the race wouldn’t go ahead. We were waiting for a break in the rain so we could go and cook some meat by the lake when we heard over the loudspeakers that the race was still on. In our role as barbecue assistants we passed free of charge through the entrance gates and, comfortably installed, watched the nation’s drivers in a fairly good car race.

Just as we were thinking of moving on, discussing the best road to take and drinking mate in the doorway of our shed, a jeep arrived, carrying some of Alberto’s friends from the distant and almost mythical Villa Concepción del Tío. We shared big friendly hugs and went immediately to celebrate by filling our guts with frothy liquid, as is the dignified practise on such occasions.

They invited us to visit them in the town where they were working, Junín de los Andes, and so we went, lessening the bike’s load by leaving our gear in the National Parks’ shed.

Exploración circunvalatoria/Circular exploration

Junín de los Andes, less fortunate than its lakeside brother, vegetates in a forgotten corner of civilization, unable to break free of the monotony of its stagnant life, despite attempts to invigorate the town by building a barracks where our friends were working. I say our friends, because in no time at all they were mine too.

We dedicated the first night to reminiscing about that distant past in Villa Concepción, our mood enhanced by seemingly unlimited bottles of red wine. My lack of training meant I had to abandon the match and, in honor of the real bed, I slept like a log.

We spent the next day fixing a few of the bike’s problems in the workshop of the company where our friends worked. That night they gave us a magnificent farewell from Argentina: a beef and lamb barbecue, with bread and gravy and a superb salad. After several days of partying, we left, departing with many hugs on the road to Carrué, another lake in the region. The road is terrible and our poor bike snorted about in the sand as I tried to help it out of the dunes. The first five kilometers took us an hour and a half, but later the road improved and we arrived without any other hitches at Carrué Chico, a little blue-green lake surrounded by wildly forested hills, and then at Carrué Grande, a more expansive lake but sadly impossible to ride around on a bike because there is only a bridle path used by local smugglers to cross over to Chile.

We left the bike at the cabin of a park ranger who wasn’t home, and took off to climb the peak facing the lake. It was nearing lunchtime and our supplies consisted only of a piece of cheese and some preserves. A duck passed, flying high over the lake. Alberto calculated the distance of the bird, the absence of the warden, the possibility of a fine, etc., and fired. By a masterful stroke of good luck (though not for the duck), the bird fell into the lake. A discussion immediately ensued as to who would go and get it. I lost and plunged in. It seemed that fingers of ice were gripping me all over my body, almost completely impeding my movement. Allergic as I am to the cold, those 20 meters there and back that I swam to retrieve what Alberto had shot down made me suffer like a Bedouin. Just as well that roast duck, flavored as usual with our hunger, is one exquisite dish.

nvigorated by lunch, we set off with enthusiasm on the climb. From the start, however, we were joined by flies that circled us ceaselessly, biting when they got the chance. The climb was gruelling because we lacked appropriate equipment and experience, but some weary hours later we reached the summit. To our disappointment, there was no panoramic view to admire; neighboring mountains blocked everything. Whichever way we looked a higher peak was in the way. After some minutes of joking about in the patch of snow crowning the peak, we took to the task of descending, spurred on by the fact that darkness would soon be closing in. The first part was easy, but then the stream that was guiding our descent began to grow into a torrent with steep, smooth sides and slippery rocks that were difficult to walk on. We had to push our way through willows on the edge, finally reaching an area of thick, treacherous reeds. As night fell it brought us a thousand strange noises and the sensation of walking into empty space with each step. Alberto lost his goggles and my pants were reduced to rags. We arrived, finally, at the tree line and from there we took every step with infinite caution, because the darkness was so complete and our sixth sense so heightened that we saw abysses every second moment.

After an eternity of trekking through deep mud we recognized the stream flowing out into the Carrué, and almost immediately the trees disappeared and we reached the flat. The huge figure of a stag dashed like a quick breath across the stream and his body, silver by the light of the rising moon, disappeared into the undergrowth. This tremor of nature cut straight to our hearts. We walked slowly so as not to disturb the peace of the wild sanctuary with which we were now communing.

We waded across the thread of water, whose touch against our ankles gave me a sharp reminder of those ice fingers I hate so much, and reached the shelter of the ranger’s cabin. He was kind enough to offer us hot mate and sheepskins to sleep on till the following morning. It was 12:35 a.m.

We drove slowly on the way back, passing lakes of only a hybrid beauty compared to Carrué, and finally reached San Martín where Don Pendón gave us 10 pesos each for working at the barbecue. Then we set off further south.

Querida vieja/Dear Mama

January 1952

En route to Bariloche

Dear Mama,

Just as you have not heard from me, I’ve had no news from you and I’m worried. It would defeat the purpose of these few lines to tell you all that has happened to us; I’ll just say that two days after leaving Bahía Blanca I fell ill with a temperature of 40 degrees which kept me in bed for a day. The following morning I managed to get up only to end up in the Choele Choel regional hospital where I was given a dose of a little-known drug, penicillin, and recovered four days later…