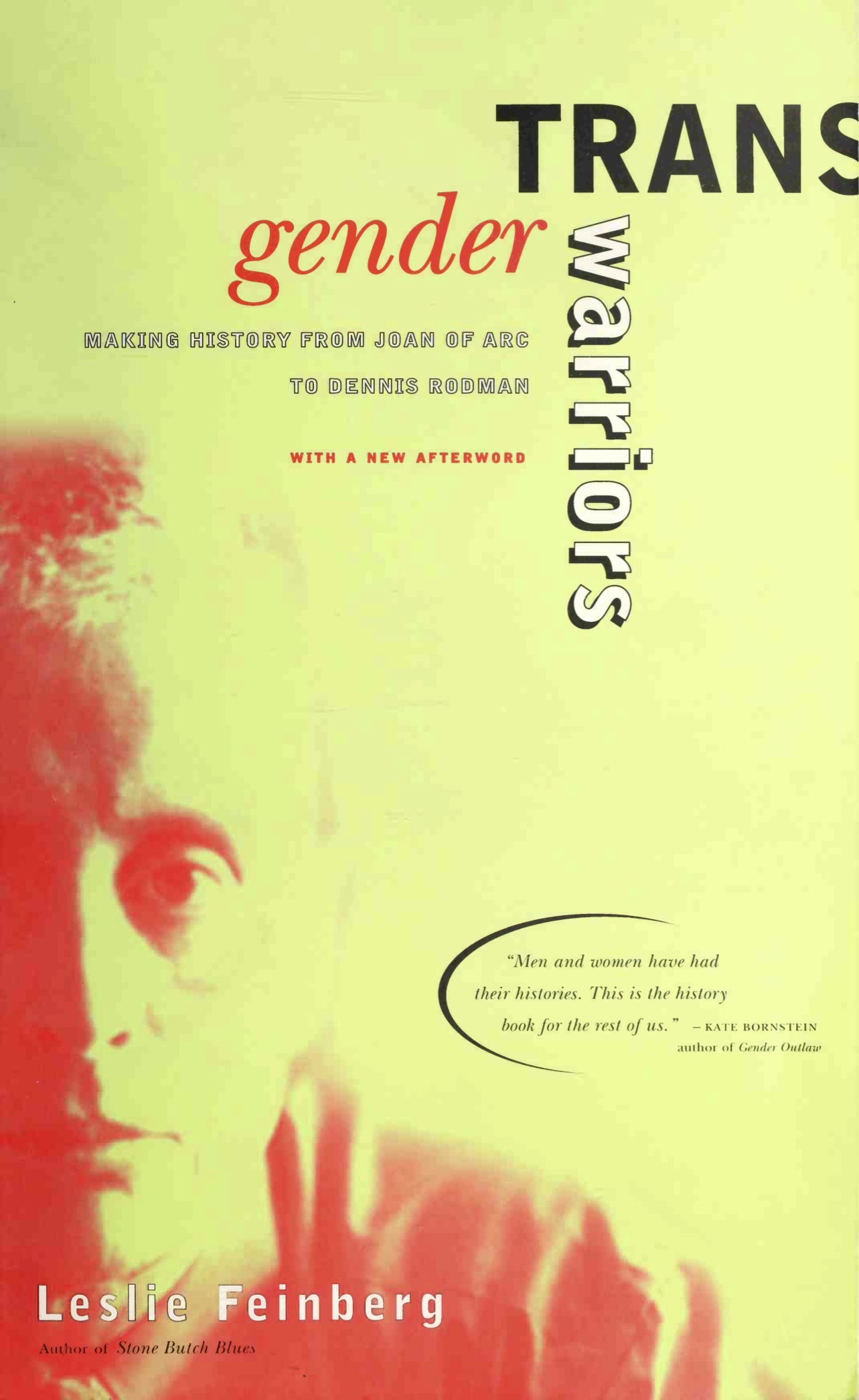

Transgender Warriors | |

|---|---|

| |

| Author | Leslie Feinberg |

| Publisher | Beacon Press |

| First published | 1996 25 Beacon Street, Boston, Massachusetts, USA |

| Edition | 1997 |

| Type | Book |

| ISBN | 9780807079416 |

| Source | https://ptilou42.files.wordpress.com/2020/01/leslie_feinberg_transgender_warriors__making_hisz-lib.org_.pdf |

Preface

"Are you a guy or a girl?"

I've heard the question all my life. The answer is not so simple, since there are no pronouns in the English language as complex as I am, and I do not want to simplify myself in order to neatly fit one or the other. There are millions more like me in the United States alone.

We have a history filled with militant hero/ines. Yet therein lies the rub! How can I tell you about their battles when the words woman and man, feminine and masculine, are almost the only words that exist in the English language to describe all the vicissitudes of bodies and styles of expression?

Living struggles accelerate changes in language. I heard language evolve during the 1960s, when I came out into the drag bars of western New York and southern Ontario. At that time, the only words used to describe us cut and seared—yelled at us from the window of a screeching car, filled with potential bashers. There were no words that we'd go out of our way to use that made us feel good about ourselves.

When we all first heard the word "gay," some of my friends vehemently opposed the word on the grounds that it made us sound happy. "No one will ever use 'gay'," my friends assured me, each offering an alternative word, none of which took root. I learned that language can't be ordered individually, as if from a Sears catalog. It is forged collectively, in the fiery heat of struggle.

Right now, much of the sensitive language that was won by the liberation movements in the United States during the sixties and seventies is bearing the brunt of a right-wing backlash against being "politically correct." Where I come from, being "politically correct" means using language that respects other peoples' oppressions and wounds. This chosen language needs to be defended.

The words I use in this book may become outdated in a very short time, because the transgender movement is still young and defining itself. But while the slogans lettered on the banners may change quickly, the struggle will rage on. Since I am writing this book as a contribution to the demand for transgender liberation, the language I'm using in this book is not aimed at definingbut at defending the diverse communities that are coalescing.

I don't have a personal stake in whether the trans liberation movement results in a new third pronoun, or gender-neutral pronouns, like the ones, such as ze (she/he) andhit(her/his), beingexperimentedwithincyberspace.Itisnotthewordsinand of themselves that are important to me—it's our lives. The struggle of trans people over the centuries is not his-story or her-story. It is owr-story.

I've been called a he-she, butch, bulldagger, cross-dresser, passing woman, female-to-male transvestite, and drag king. The word I prefer to use to describe myselfis transgender.

Today the word transgender has at least two colloquial meanings. It has been used as an umbrella term to include everyone who challenges the boundaries of sex and gender. It is also used to draw a distinction between those who reassign the sex they were labeled at birth, and those of us whose gender expression is considered inappropriate for our sex. Presently, many organizations—from Transgender Nation in San Francisco to Monmouth Ocean Transgender on theJersey shore—use this term inclusively.

I asked many self-identified transgender activists who are named or pictured in this book who they believed were included under the umbrella term. Those polled named: transsexuals, transgenders, transvestites, transgenderists, bigenders, drag queens, drag kings, cross-dressers, masculine women, feminine men, intersexuals (people referred to in the past as "hermaphrodites"), androgynes, cross-genders, shape-shifters, passing women, passing men, gender-benders, gender-blenders, bearded women, and women bodybuilders who have crossed the line of what is considered socially acceptable for a female body.

But the word transgender is increasingly being used in a more specific way as well. The term transgenderist was first introduced into the English language by trans warrior Virginia Prince. Virginia told me, "I coined the noun transgenderist in 1987 or '88. There had to be some name for people like myself who trans the gender barrier—meaning somebody who lives full time in the gender opposite to their anatomy. I have not transed the sex barrier."

As the overall transgender movement has developed, more people are exploring this distinction between a person's sex—female, intersexual, male—and their gender expression—feminine, androgynous, masculine, and other variations. Many national and local gender magazines and community groups are starting to use TS/TG: transsexual and transgender.

Under Western law, doctors glance at the genitals of an infant and pronounce the baby female or male, and that's that. Transsexual men and women traverse the boundary of the sex they were assigned at birth.

And in dominant Western cultures, the gender expression of babies is assumed at birth: pink for girls, blue for boys; girls are expected to grow up feminine, boys masculine. Transgender people traverse, bridge, or blur the boundary of the gender expression they were assigned at birth.

However, not all transsexuals choose surgery or hormones; some transgender people do. I am transgender and I have shaped myself surgically and hormonally twice in my life, and I reserve the right to do it again.

But while our movement has introduced some new terminology, all the words used to refer to our communities still suffer from limitations. For example, terms like cross-dress, cross-gender, male-to-female, and female-to-male reinforce the idea that there are only two distinct ways to be—you're either one or the other—and that's just not true. Bigender means people have both a feminine side and a masculine side. In the past, most bigendered individuals were lumped together under the category of cross-dressers. However, some people live their whole lives crossdressed; others are referred to as part-time cross-dressers. Perhaps if gender oppression didn't exist, some of those part-timers would enjoy the freedom to cross-dress all the time. But bigendered people want to be able to express both facets of who they are.

Although I defend any person's right to use transvestite as a s^Z/definition, I use the term sparingly in this book. Although some trans publications and organizations still use "transvestite" or the abbreviation "TV" in their titles, many people who are labeled transvestites have rejected the term because it invokes concepts of psychological pathology, sexual fetishism, and obsession, when there's really nothing at all unhealthy about this form of self-expression. And the medical and psychiatric industries have always defined transvestites as males, but there are many female cross-dressers as well.

The words cross-dresser, transvestite, and drag convey the sense that these intricate expressions of self revolve solely around clothing. This creates the impression thatifyou'resooppressedbecauseofwhatyou'rewearing,youcanjustchangeyour outfit! But anyone who saw La Cage aux Folks remembers that the drag queen never seemed more feminine than when she was crammed into a three-piece "man's" suit and taught to butter bread like a "real man." Because it is our entire spirit—the essence of who we are—that doesn't conform to narrow gender stereotypes, many people who in the past have been referred to as cross-dressers, transvestites, drag queens, and drag kings today define themselves as Iransgender.

All together, our many communities challenge all sex and gender borders and restrictions. The glue that cements these diverse communities together is the defense of the right of each individual to define themselves.

As I write this book, the word trans is being used increasingly by the gender community as a term uniting the entire coalition. If the term had already enjoyed popular recognition, I would have titled this book Trans Warriors. But since the word transgender is still most recognizable to people all over the world, I use it in its most inclusive sense: to refer to all courageous trans warriors of every sex and gender those who led battles and rebellions throughout history and those who today muster the courage to battle for their identities and for their very lives.

Transgender Warriors is not an exhaustive trans history, or even the history of the rise and development of the modern trans movement. Instead, it is a fresh look at sex and gender in history and the interrelationships of class, nationality, race, and sexuality. Have all societies recognized only two sexes? Have people who traversed the boundaries of sex and gender always been so demonized? Why is sex-reassignment or cross-dressing a matter of law?

But how could I find the answers to these questions when it means wending my way through diverse societies in which the concepts of sex and gender shift like sand dunes over the ages? And as a white, transgender researcher, how can I avoid foisting my own interpretations on the cultures of oppressed peoples' nationalities?

I tackled this problem in several ways. First, I focused a great deal of attention on Western Europe, not out of unexamined Eurocentrism, but because I hold the powers that ruled there for centuries responsible for campaigns of hatred and bigotry that are today woven into the fabric of Western cultures and have been imposed upon colonized peoples all over the world. Setting the blame for these attitudes squarely on the shoulders of the European ruling classes is part of my contribution to the anti-imperialist movements.

I've also included photos from cultures all over the world, and I've sought out people from those countries and nationalities to help me create short, factual captions. I tried very hard not to interpret or compare these different cultural expressions. These photographs are not meant to imply that the individuals pictured identify themselves as transgender in the modern, Western sense of the word. Instead, I've presented their images as a challenge to the currently accepted Western dominant view that woman and man are all that exist, and that there is only one waytobeawomanoraman.

I don't take a view that an individual's gender expression is exclusively a product of either biology or culture. If gender is solely biologically determined, why do rural women, for example, tend to be more "masculine" than urban women? On the other hand, if gender expression is simply something we are taught, why has such a huge trans segment of the population not learned it? If two sexes are an immutable biological fact, why have so many societies recognized more than two? Yet while biology is not destiny, there are some biological markers on the human anatomical spectrum. So is sex a social construct, or is the rigid categorization of sexes the cultural component? Clearly there must be a complex interaction between individuals and their societies.

My interest in this subject is not merely theoretical. You probably already know that those of us who cross the cultural boundaries of sex and gender are paying a terrible price. We face discrimination and physical violence. We are denied the right to live and work with dignity and respect. It takes so much courage to live our lives that sometimes just leaving our homes in the morning and facing the world as who we really are is in itself an act of resistance. But perhaps you didn't know that we have a history of fighting against such injustice, and that today we are forging a movement for liberation. Since I couldn't include photos of all the hard-working leading activists who make up our movement, I have included a collection of photos that begins to illustrate the depth and breadth of sex and gender identities, balanced bv race, nationality, and region. No one book could include all the sundry identities of trans individuals and organizations, which range from the Short Mountain Fairies from Tennessee to the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence in San Francisco.

It is time for us to write as experts on our own histories. For too long our light has been refracted through other people's prisms. My goal in this book is to fashion history, politics, and theory into a steely weapon with which to defend a very oppressed segment of the population.

I grew up thinking that the hatred I faced because of my gender expression was simply a by-product of human nature, and that it must be my fault that I was a target for such outrage. I don't want any young person to ever believe that's true again, and so I wrote this book to lay bare the roots and tendrils of sex and gender oppression.

Today, a great deal of "gender theory" is abstracted from human experience. But if theory is not the crystallized resin of experience, it ceases to be a guide to action. I offer history, politics, and theory that live and breathe because they are rooted in the experience of real people who fought flesh-and-blood battles for freedom. And my work is not solely devoted to chronicling the past, but is a component of my organizing to help shape the future.

This is the heart of my life's work. When I clenched my fists and shouted back at slurs aimed to strip me of my humanity, this was the certainty behind my anger. When I sputtered in pain at well-meaning individuals who told me, "I just don't get what you are?"—this is what I meant. Today, Transgender Warriors is my answer. This is the core of my pride.

Acknowledgements

I've been forced to pack up and move quickly many times in the last twenty years—spurred by my inability to pay the rent or, all too often, by a serious threat to my life that couldn't be faced down. Yet no matter how much I was forced to leave behind, I always schlepped my cartons of transgender research with me. Thanks to my true friends who got up in the middle of the night, wiped the sleep from their eyes, and helped me move. You rescued my life, and my work.

Over the decades, my writings on trans oppression, resistance, and history have appeared as articles in Workers World newspaper, and Liberation and Marxism magazine. I have spoken about these topics at countless political meetings, street rallies, and activist conferences. So I thank the members of Workers World Party—of every nationality, sex, age, ability, gender, and sexuality—for liberating space for me, helping me develop, and defending a podium from which I could speak about trans liberation as a vital component of the struggle for economic and socialjustice.

Some special thanks. To Gregory Dunkel for waking me some twenty years ago to the need to archive the images I'd found, and then helping me every step of the way. To Sara Flounders, for proving to be such a good friend and ally to the trans communities—and to me. My gratitude and love for Dorothy Ballan is right here in my heart. I'm especiallv grateful for the unflagging support from my transsexual, transgender, drag, and intersexual comrades—especially Kristianna Tho'mas.

In 1992 I wrote the pamphlet Transgender Liberation: A Movement Whose Time Has Come, which became the basis for my slide show. I traveled the country showing slides in places as diverse as an auditorium at Brown University and a back room of a pizzeria/bar in Little Rock, Arkansas. Thousands of you asked questions during or after the program, which contributed to this finished work. Maybe you sent me a clipping, photo, or book reference. You've all offered me support. I am grateful for this kindness and solidarity.

My gratitude to each of the trans warriors included in this book. But many other transsexual, transgender, drag, intersexual, and bigender warriors gave me a heap of help and support, including: Holly Boswell, Cheryl Chase, Loren Cameron, Dallas Denny and the valuable resources of the National Transgender Library and Archive, Lissa Fried, Dana Friedman, Davina Anne Gabriel, James Green, David Harris, Mike Hernandez, Craig Hickman, Morgan Holmes, Nancy Nangeroni, Linda and Cynthia Phillips, Bet Power, Sky Renfro, Martine and Bina Rothblatt, Ruben, Gail Sondegaard, Susan Stryker, Virginia Prince, Lynn Walker, Riki Wilchins, andJessy Xavier.

Chrystos, you really served as editor of Chapter 3; I loved working with you! Thanks to other friends and allies who also gently helped me to express my solidarity with people of other nationalities in the most sensitive possible way: Yamila Azize-Vargas, my beloved Nic Billey, Ben the Dancer, Spotted Eagle, Elias Fara-

jaje-Jones, Curtis Harris, Larry Holmes, Leota Lone Dog, Aurora Levins Morales, Pauline Park, Geeta Patel, Doyle Robertson, Barbara Smith, Sabrina Sojourner, and Wesley Thomas.

Then there was the research. Leslie Kahn, you are my goddess of transgender library research. Miriam Hammer, I will always remember you coming to my home at the eleventh hour after I'd lost my manuscript and research to a computer virus. Thanks to Allan Berube, Melanie Breen, Paddy Colligan, Randy P. Conner, Bill Dragoin, Anne Fausto-Sterling, Jonathan Ned Katz, and Julie Wheelwright.

My warmest thanks to Morgan Gwenwald and Mariette Pathy Allen—who worked on this project as photographic consultants and advisors. Amv Steiner. thanks! And I owe a debt of gratitude to the many brilliant documentary and art photographers, amateur shutterbugs, graphic artists, and a wildly popular cartoonist—who all contributed to this book. Special thanks to Marcus Alonso, Alison Bechdel, Loren Cameron, Stephanie Dumaine, Greg Dunkel, Robert Giard, Steve Gillis, Andrew Holbrooke, Jennie Livingston, Viviane Moos, John Nafpliotis, Lyn Neely, V.Jon Nivens, Cathy Opie, M. P. Schildmeyer, Bette Spero, Pierre Verger, and Gary Wilson. And my regards to the darkroom folks, particularlyLigiaBotersandBrianYoungatPhototechnica,andtheguysatHongColor.

As I saw how much archivists, librarians, and researchers all over the world cared about preserving our collective past and making it accessible, mv respect for their work soared. Special thanks to archivistJanet Miller, and your Uncommon Vision, and the staffs of the Schomburg Collection, Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institute (especially Vertis), Library of Congress, State Hermitage Museum of Russia, Mansell Collection, British Library, National Library of Wales, Royal Anthropological Institute, British Museum, Louvre, American Library Association, Bettmann Archive, New York Public Library, Musee de Beaux Arts de Rouen, Staatliche Museen, Clarke Historical Library, Verger Institute, Nationalmuseum Stockholm, Cleveland Museum of Art, Guildhall Library, and Art Resource.

For support that came in many forms, my gratitude to: John Catalinotto. Kate Clinton, Hillel Cohen, Annette Dragon, Bob Diaz, Ferron, Nanette Gartrell, Diane McPherson, Dee Mosbacher, Joy Schaefer, Adrienne Rich. Beth Zemsky, and Carlos Zuriiga.

To my agent, Charlotte Sheedy—it's an honor to work with a pioneer who marked the trail for so many of us. To Deb Chasman, my editor at Beacon—you've demonstrated that editing genius is sharp style, and a whole lot of sensitivity. My gratitude to Ken Wong for grammatically scrubbing this book. And I thank the whole staff at Beacon for their contributions—not the least of which was enthusiastic support.

Thanks to those whose astute reading of my drafts greatly developed this book—especially Elly Bulkin and Deirdre Sinnott. For teaching me how to be a journalist, over two decades, I credit you, Deirdre Griswold—longtime editor, longtime friend.

Now I go a bit deeper. Thanks to my sons—Ben and Ransom—for loving and supporting your Drag Dad. I love you each dearly. To my sister Catherine, and my "chosen family"—Star, Shelley, Robin, Brent and my mom Wyontmusqui—how else can I thank you for your love except to love you right back.

To my wife, my inspiration, and my dearest friend, poet-warrior Minnie Bruce Pratt—1 couldn't have gotten through this without you. I've stoop-picked beans and stretch-picked apples, but this book was the hardest work I've ever done.

Your brilliance, insight, and generous love got me through each day. How could I possibly thank you in the way you deserve? Tell you what—As we grow old happily—one day at a time—I'll try to find the ways.

The sum total of everyone's contributions to this book is a collective act of solidarity with trans liberation. Since the movement to bring a better world into birth developed me and my world view, I give this book—and every cent of the advance royalties, an author's wages—back to the struggle to end all oppression.

Part 1

The Journey Begins

When I was born in 1949, the doctor confidently declared, "It's a girl." That might have been the last time anyone was so sure. I grew up a very masculine girl. It's a simple statement to write, but it was a terrifying reality to live.

I was raised in the 1950s - an era marked by rigidly enforced social conformity and fear of difference. Our family lived in the Bell Aircraft factory housing projects. The roads were not paved; the coal truck, ice man's van, and knife-sharpener's cart crunched along narrow strips of gravel.

I tried to mesh two parallel worlds as a child - the one I saw with my own eyes and the one I was taught. For example, I witnessed powerful adult women in our work- ing-class projects handling every challenge of life, while coping with too many kids and not enough money. Although I hated seeing them so beaten down by poverty, I loved their laughter and their strength. But, on television I saw women depicted as foolish and not very bright. Every cultural message taught me that women were only capable of being wives, mothers, housekeepers - seen, not heard. So, was it true that women were the "weak" sex?

In school I leafed through my geography textbooks and saw people of many dif- ferent hues from countries far, far from my home. Before we moved to Buffalo, my family had lived in a desert town in Arizona. There, people who were darker skinned and shared different customs from mine were a sizeable segment of the population. Yet in the small world of the projects, most of the kids in my grade school, and my teachers, were white. The entire city was segregated right down the middle - east and west. In school I listened as some teachers paid lip service to "tolerance" but I frequently heard adults mouth racist slurs, driven by hate.

I saw a lot of love. Love of parents, flag, country, and deity were mandatory. But I also observed other loves - between girls and boys, and boys and boys, and girls and girls. There was the love of kids and dogs in my neighborhood, soldier buddies in foxholes in movies, students and teachers at school. Passionate, platonic, sensual, dutiful, devoted, reluctant, loyal, shy, reverent. Yet I was taught there was only one official meaning of the word love- the kind between men and women that leads to marriage. No adult ever mentioned men loving men or women loving women in my presence. I never heard it discussed anywhere. There was no word at that time in my Englishlanguagetoexpressthesheerjoyoflovingsomeoneofthesamesex.

And I learned very early on that boys were expected to wear "men's" clothes, and girls were not. When a man put on women's garb, it was considered a crude joke. By the time my family got a television, I cringed as my folks guffawed when "Uncle Miltie" Berle donned a dress. It hit too close to home. I longed to wear the boys' clothing I saw in the Sears catalog.

My own gender expression felt quite natural. I liked my hair short and I felt most relaxed in sneakers, jeans and a t-shirt. However, when I was most at home with how I looked, adults did a double-take or stopped short when they saw me. The question "Is that a boy or a girl?" hounded me throughout my childhood. The answer didn't matter much. The very fact that strangers had to ask the question already marked me as a gender outlaw.

My choice of clothing was not the only alarm bell that rang my difference. If my more feminine younger sister had worn "boy's" clothes, she might have seemed styl- ish and cute. Dressing all little girls and all little boys in "sex-appropriate" clothing actually called attention to our gender differences. Those of us who didn't fit stuck out like sore thumbs.

Being different in the 1950s was no small matter. McCarthy's anti-communist witch hunts were in full frenzy. Like most children, I caught snippets of adult conversa- tions. So I was terrified that communists were hiding under my bed and might grab my ankles at night. I heard that people who were labeled "reds" would discover their names and addresses listed in local newspapers, be fired from their jobs, and be forced to pack up their families and move away. What was their crime? I couldn't make out the adults' whispers. But the lesson seeped down: keep your mouth shut; don't rock the boat. I overheard angry, hammering accusations on radio and televi- sion against grownups who had to answer to a committee of men. I heard the words: commie, pinko,Jew. I wasJewish.

We were the onlyJews in the projects. Our family harbored memories of the hor- rors that relatives and friends had faced in Czarist Russia before the 1917 revolution and in Eastern Europe during World War II. My family lived in fear of fascism, and the McCarthy era stank like Nazism. Every time a stranger stopped us on the street and asked my parents, "Is that a boy or a girl?" they shuddered. No wonder. My parents worried that I was a lightning rod that would attract a dangerous storm. Feeling helpless to fight the powers that be, they blamed the family's problems on me and my difference. I learned that my survival was my own responsibility. From kindergarten to high school, I walked through a hail of catcalls and taunts in school corridors. I pushed my way past clusters of teenagers on street corners who refused to let me pass. I endured the stares and glares of adults. It was so hard to be a masculine girl in the 1950s that I thought I would cer- tainly be killed before I could grow to adulthood. Every gender image - from my Dick andJane textbooks in school to the sitcoms on television - convinced me that I must be a Martian.

In all the years of my childhood, I had only heard of one person who seemed similarly "different." I don't remember any adult telling me her name. I was too young to read the newspaper headlines. Adults clipped their vulgar jokes short when I, or any other child, entered the room. I wasn't allowed to stay up late enough to watch the television comedy hosts who tried to ridicule her out of humanity.

But I did know her name: Christine Jorgensen.

I was three years old when the news broke that Christine Jorgensen had traveled from the United States to Sweden for a sex change from male to female. A passport agent reportedly sold the story to the media. All hell broke loose. In the years that followed, just the mention of her name provoked vicious laughter. The cruelty must have filtered down to me, because I understood that the jokes rotated around whether Christine Jorgensen was a woman or a man. Everyone was supposed to eas- ily fit into one category or another, and stay there. But I didn't fit, so Christine Jor- gensen and I had a special bond. By the time I was eight or nine years old, I had asked a baby-sitter, "Is Christine Jorgensen a man or a woman?"

"She isn't anything," my baby-sitter giggled. "She's a freak." Then, I thought, I must be a freak too, because nobody seemed sure whether I was a boy or a girl. What was going to happen to me? Would I survive? Would Christine survive?

As it turned out, Christine Jorgensen didn't just endure, she triumphed. I knew she must be living with great internal turmoil, but she walked through the abuse with her head held high. Just as her dignity and courage set a proud example for the thou- sands of transsexual men and women who followed her path, she inspired me - and who knows how many other transgendered children.

Little did I know then that millions of children and adults across the United States and around the world also felt like the only person who was different. I had no other adult role model who crossed the boundaries of sex or gender. Christine Jorgensen's struggle beamed a message to me that I wasn't alone. She proved that even a period of right-wing reaction could not coerce each individual into conformity.

I survived growing up transgendered during the iron-fisted repression of the 1950s. But I came of age and consciousness during the revolutionary potential of the 1960s - from the Civil Rights movement to the Black Panther Party, from the Young Lords to the American Indian movement, from the anti-Vietnam War strug- gles to women's liberation. The lesbian and gay movement had not yet emerged. But as a teenager, I found the gay bars in Niagara Falls, Buffalo, and Toronto. Inside those smoke-filled taverns I discovered a community of drag queens, butches, and femmes. This was a world in which I fit; I was no longer alone.

It meant the world to me to find other people who faced many of the same problems I did. Continual violence stalked me on the streets, leaving me weary, so of course I wanted to be with friends and loved ones in the bars. But the clubs were not a safe sanctuary. I soon discovered that the police and other enemies preyed on us there. Until we organized to fight back, we were just a bigger group of people to bash.

But we did organize. We battled for the right to be hired, walk down the street, be served in a restaurant, buy a carton of milk at a store, play softball or bowl. Defend- ing our rights to live and love and work won us respect and affection from our straight co-workers and friends. Our battles helped fuel the later explosion of the lesbian and gay liberation movement.

I remember the Thaw Out Picnic held each spring during the sixties by the lesbian and gay community in Erie, Pennsylvania. Hundreds and hundreds of women and men would fill a huge park to enjoy food, dancing, softball, and making out in the woods. During the first picnic I attended, a group of men screeched up in a car near the edge of the woods. Suddenly the din of festivity hushed as we saw the gang, armed with baseball bats and tire irons, marching down the hill toward us.

"C'mon," one of the silver-haired butches shouted, beckoning us to follow. She picked up her softball bat and headed right for those men. We all grabbed bats and beer bottles and followed her, moving slowly up the hill toward the men. First they jeered us. Then they glanced fearfully at each other, leaped back into their car and peeled rubber. One of them was still trying to get his legs inside and shut the car door as they roared off. We all stood quietly for a moment, feeling our collective power. Then the old butch who led our army waved her hand and the celebration resumed.

My greatest terror was always when the police raided the bars, because thev had the law on their side. They were the law. It wasn'tjust the tie I was wearing or the suit coat that made me vulnerable to arrest. I broke the law every time I dressed in fly- front pants, or wore jockey shorts or t-shirts. The law dictated that I had to wear at least three pieces of "women's" clothing. My drag queen sisters had to wear three pieces of "men's" clothing. For all I know, that law may still be on the books in Buffalo today.

Of course, the laws were not simply about clothing. We were masculine women and feminine men. Our gender expression made us targets. These laws were used to harass us. Frequently we were not even formally charged after our arrests. All too often, the sentences were executed in the back seat of a police cruiser or on the cold cement floor of a precinct cell.

But the old butches told me there was one night of the year that the cops never arrested us - Halloween. At the time, I wondered why I was exempt from penalties for cross-dressing on that one night. And I grappled with other questions. Why was I subject to legal harassment and arrest at all? Why was I being punished for the way I walked or dressed, or who I loved? Who wrote the laws used to harass us, and why? Who gave the green light to the cops to enforce them? Who decided what was nor- mal in the first place?

These were life-and-death questions for me. Finding the answers sooner would have changed my life dramatically. But the journey to find those answers is my life. And I would not trade the insights and joys of my lifetime for anyone else's.

This was how myjourney began. It was 1969 and I was twenty years old. As I sat in a gay bar in Buffalo, a friend told me that drag queens had fought back against a police bar raid in New York City. The fight had erupted into a four-night-long uprising in Greenwich Village - the Stonewall Rebellion! I pounded the bar with my fist and cursed my fate. For once we had rebelled and made history and I had missed it!

I stared at my beer bottle and wondered: Have we always existed? Have we always been so hated? Have we always fought back?

My Path to Consciousness

The Give Away

I found my first clue that trans people have not always been hated in 1974. I had played hooky from work and spent the day at the Museum of the American Indian in New York City.

The exhibits were devoted to Native history in the Americas. I was drawn to a display of beautiful thumb-sized clay figures. The ones to my right had breasts and cradled bowls. Those on the left were flat chested, holding hunting tools. But when I looked closer, I did a double-take. I saw that several of the figures holding bowls were flat chested; several of the hunters had breasts. You can bet there was no legend next to the display to explain. I left the museum curious.

What I'd seen gnawed at me until I called a member of the curator's staff. He asked, "Why do you want to know?" I panicked. Was the information so classified that it could only be given out on a "need to know" basis? I lied and said I was a graduate student at Columbia University.

Sounding relieved, he immediately let me know that he understood exactly what I'd described. He said he came across references to these berdache[1] practically every day in his reading. I asked him what the word meant. He said he thought it meant transvestite or transsexual in modern English. He remarked that Native peoples didn't seem to abhor them the way "we" did. In fact, he added, it appeared that such individuals were held in high esteem by Native nations.

Then his voice dropped low. "It's really quite disturbing, isn't it?" he whispered. I hung up the phone and raced to the library. I had found the first key to a vault containing information I'd looked for all my life.

"Strange country this," a white man wrote in 1850 about the Crow nation ofNorth America, "where males assume the dress and perform the duties of females,while women turn men and mate with their own sex!"

I found hundreds and hundreds of similar references, such as those in JonathanNed Katz's ground-breaking Gay American History: Lesbians and Gay Men in the U.S.A.,published in 1976, which provided me with additional valuable research. The quotes were anything but objective. Some were statements by murderouslv hostilecolonial generals, others by the anthropologists and missionaries who followed intheir bloody wake.

Some only referred to what today might be called male-to-female expression. "Innearly every part of the continent," Westermarck concluded in 191 7, "there seemtohave been, since ancient times, men dressing themselves in the clothes and per-forming the functions of women. . .."2

But I also found many references to female-to-male expression. Writing about hisexpedition into northeastern Brazil in 1576, Pedro de Magalhaes noted femalesamong the Tupinamba who lived as men and were accepted by other men. and whohunted and went to war. His team of explorers, recalling the Greek Amazons,renamed the river that flowed through that area the River ofthe Amazons.

Female-to-male expression was also found in numerous North Americannations. As late as 1930, ethnographer Leslie Spier observed of a nation in thePacific Northwest: "Transvestites or berdaches ... are found among the Klamath, asin all probability among all other North American tribes. These are men andwomen who for reasons that remain obscure take on the dress and habits of theopposite sex."4

I found it painful to read these quotes because they were steeped in hatred. "I sawa devilish thing," Spanish colonialist Alvar Nunez Cabeza de Vaca wrote in the sixteenth century.5 "Sinful, heinous, perverted, nefarious, abominable, unnatural, dis-gusting, lewd"—the language used by the colonizers to describe the acceptance ofsex/gender diversity, and of same-sex love, most accurately described the viewer,not the viewed. And these sensational reports about Two-Spirit people were used tofurther "justify" genocide, the theft of Native land and resources, and destruction oftheir cultures and religions.

But occasionally these colonial quotes opened, even if inadvertently, a momentary window into the humanity of the peoples being observed. Describing his first trip down the Mississippi in the seventeenth century, Jesuit Jacques Marquette chronicled the attitudes of the Illinois and Nadouessi to the Two-Spirits. "They are summoned to the Councils, and nothing can be decided without their advice. Finally, through their profession of leading an Extraordinary life, they pass for Manitous,—That is to say, for Spirits,—or persons of Consequence."6

Although French missionary Joseph Francois Lafitau condemned Two-Spirit people he found among the nations of the western Great Lakes, Louisiana, and Florida, he revealed that those Native peoples did not share his prejudice. "They believe they are honored ..." he wrote in 1 724, "they participate in all religious ceremonies, and this profession of an extraordinary life causes them to be regarded as people of a higher order. . . . " 7

But the colonizers' reactions toward Two-Spirit people can be summed up by the words of Antonio de la Calancha, a Spanish official in Lima. Calancha wrote that during Vasco Nunez de Balboa's expedition across Panama, Balboa "saw men dressed like women; Balboa learnt that they were sodomites and threw the king and forty others to be eaten by his dogs, a fine action of an honorable and Catholic Spaniard."8

This was not an isolated attack. When the Spaniards invaded the Antilles and Louisiana, "they found men dressed as women who were respected by their societies. Thinking they were hermaphrodites, or homosexuals, they slew them."9

Finding these quotes shook me. I recalled the "cowboys and Indians" movies of my childhood. These racist films didn't succeed in teaching me hate; I had grown up around strong, proud Native adults and children. But I now realized more consciously how every portrayal of Native nations in these movies was aimed at diverting attention from the real-life colonial genocide. The same bloody history was ignored or glossed over in my schools. I only learned the truth about Native cultures later, by re-educating myself—a process I'm continuing.

Discovering the Two-Spirit tradition had deep meaning for me. It wasn't that I thought the range of human expression among Native nations was identical to trans identities today. I knew that a Crow bade, Cocopa warhameh, Chumash joya, and Maricopa kwiraxame' would describe themselves in very different ways from an African-American drag queen fighting cops at Stonewall or a white female-to-male transsexual in the 1990s explaining his life to a college class on gender theory.

What stunned me was that such ancient and diverse cultures allowed people to choose more sex/gender paths, and this diversity of human expression was honored as sacred. I had to chart the complex geography of sex and gender with a compass needle that only pointed to north or south.

You'd think I'd have been elated to find this new information. But I raged thatthese facts had been kept from me, from all of us. And so many of the Native peopleswho were arrogantly scrutinized by military men, missionaries, and anthropologistshad been massacred. Had their oral history too been forever lost?

In my anger, I vowed to act more forcefully in defense of the treaty, sovereignty,and self-determination rights of Native nations. As I became more active in thesestruggles, I began to hear more clearly the voices of Native peoples who not onlyreclaimed their traditional heritage, but carried the resistance into the present: thetakeover of Alcatraz, the occupation of Wounded Knee, the Longest Walk, the Davof Mourning at Plymouth Rock, and the fight to free political prisoners likeLeonard Peltier and NormaJean Croy.

Two historic developments helped me to hear the voices of modern Native warriors who lived the sacred Two-Spirit tradition: the founding of Gav American Indi-ans in 1975 by Randy Burns (Northern Paiute) and Barbara Cameron (LakotaSioux), and the publication in 1988 of Living the Spirit: A Gay American Indian Anthology. Randy Burns noted that the History Project of Gay American Indians "has documented these alternative gender roles in over 135 North American tribes." 10

Will Roscoe, who edited Living the Spirit, explained that this more complexsex/gender system was found "in every region of the continent, among ever) typeof native culture, from the small bands of hunters in Alaska to the populous, hierar-chical city-states in Florida." 11

Another important milestone was the 1986 publication of The Spirit and the Flesh 12 by Walter Williams, because this book included the voices of modern TwoSpirit people.

I knew that Native struggles against colonialization and genocide—both physical and cultural—were tenacious. But I learned that the colonizers' efforts to outlaw, punish, and slaughter the Two-Spirits within those nations had also met with fierce resistance. Conquistador Nurio de Guzman recorded in 1530 that the last person taken prisoner after a battle, who had "fought most courageously, was a man in the habit of a woman. . . ." 13

Just trying to maintain a traditional way of life was itself an act of resistance. Williams wrote, "Since in many tribes berdaches were often shamans, the government's attack on traditional healing practices disrupted their lives. Among the Klamaths, the government agent's prohibition of curing ceremonials in the 1870s and 1880s required shamans to operate underground. The berdache shaman White Cindy continued to do traditional healing, curing people for decades despite the danger of arrest."14

Native nations resisted the racist demands of U.S. government agents who tried to change Two-Spirit people. This defiance was especially courageous in light of the power these agents exercised over the economic survival of the Native people they tried to control. One such struggle focused on a Crow bade (bote) named Osh-Tisch (Finds Them and Kills Them). An oral history by Joe Medicine Crow in 1982 recalled the events: "One agent in the late 1890s . . . tried to interfere with Osh-Tisch, who was the most respected bade. The agent incarcerated the bades, cut off their hair, made them wear men's clothing. He forced them to do manual labor, planting these trees that you see here on the BIA grounds. The people were so upset with this that Chief Pretty Eagle came into Crow Agency, and told [the agent] to leave the reservation. It was a tragedy, trying to change them."15

How the bades were viewed within their own nation comes across in this report by S. C. Simms in 1903 in American Anthropologist: "During a visit last year to the Crow reservation, in the interest of the Field Columbian Museum, I was informed that there were three hermaphrodites in the Crow tribe, one living at Pryor, one in the Big Horn district, and one in Black Lodge district. These persons are usually spoken of as 'she,' and as having the largest and best appointed tipis; they are also generally considered to be experts with the needle and the most efficient cooks in the tribe, and they are highly regarded for their many charitable acts....

"A few years ago an Indian agent endeavored to compel these people, under threat of punishment, to wear men's clothing, but his efforts were unsuccessful."16

White-run boarding schools played a similar role in trying to force generations of kidnapped children to abandon their traditional ways. But many Two-Spirit children escaped rather than conform.

Lakota medicine man Lame Deer told an interviewer about the sacred place of the winkte ("male-to-female") in his nation's traditions, and how the winkte bestowed a special name on an individual. "The secret name a winkte gave to a child was believed to be especially powerful and effective," Lame Deer said. "Sitting Bull, Black Elk, even Crazy Horse had secret winkte names." Lakota chief Crazy Horse reportedly had one or two winktemves. 17

Williams quotes a Lakota medicine man who spoke of the pressures on the winktes in the 1920s and 1930s. "Themissionaries and the governmentagents said winktes were no good, andtried to get them to change their ways.Some did, and put on men's clothing.But others, rather than change, wentout and hanged themselves."18

Up until 1989, the Two-Spirit voices I heard lived only in the pages of books.But that year I was honored to beinvited to Minneapolis for the first gathering of Two-Spirit Native people, theirloved ones, and supporters. The bondsof friendship I enjoyed at the first eventwere strengthened at the third gathering in Manitoba in 1991. There, I foundmyself sitting around a campfire at thebase of tall pines under the rolling col-ors of the northern lights,drinking strong tea out ofametal cup. I laughed easilyrelaxed with old friends andnew ones. Some were feminine men or masculinewomen; all shared same-sexdesire. Yet not all of thesepeople were transgendered,and not all of the Two-Spirits I'd readabout desired people of the same sex.Then what defined this group?

I turned to Native people for theseanswers. Even today, in 1995. I readresearch papers and articles aboutsex/gender systems in Native nations in which every source cited is a white socialscientist. When I began to write thisbook, I asked Two-Spirit people to talkabout their own cultures, in their ownwords.

Chrystos, a brilliant Two-Spirit poet and writer from the Menominee nation, offered me this understanding:"Life among First Nation people,before first contact, is hard to reconstruct. There's been so much abuse of traditional life by the Christian Church. But certain things have filtered down to us. Most of the nations that I know of traditionally had more than two genders. It varies from tribe to tribe. The concept of Two-Spiritedness is a rather rough translation into English of that idea. I think the English language is rigid, and the thought patterns that form it are rigid, so that gender also becomes rigid.

"The whole concept ofgender is more fluid in traditional life. Those paths are not necessarily aligned with your sex, although they may be. People might choose their gender according to their dreams, for example. So even the idea that your gender is something you dream about is not even a concept in Western culture—which posits you are born a certain biological sex and therefore there's a role you must step into and follow pretty rigidly for the rest of your life. That's how we got the concept ofqueer. Anyone who doesn't follow their assigned gender role is queer; all kinds of people are lumped together under that word."19

Does being Two-Spirit determine your sexuality? I asked Chrystos. "In traditional life a Two-Spirit person can be heterosexual or what we would call homosexual," she replied. "You could also be a person who doesn't have sex with anyone and lives with the spirits. The gender fluidity is part of a larger concept, which I guess the most accurate English word for is 'tolerance.' It's a whole different way of conceiving how to be in the world with other people. We think about the world in terms of relationship, so each person is always in a matrix, rather than being seen only as an individual—which is a very different way of looking at things."20

Chrystos told me about her Navajo friend Wesley Thomas, who describes himself as nadleeh-like. A male nadleeh, she said, "would manifest in the world as a female and take a husband and participate in tribal life as a female person." I e-mailed Wesley, who lives in Seattle, for more information about the nadleeh tradition. He wrote back that "nadleeh was a category for women who were/are masculine and also feminine males."21

The concept of nadleeh, he explained, is incorporated into Navajo origin or creation stories. "So, it is a cultural construction," he wrote, "and was part of the normal Navajo culture, from the Navajo point of view, through the nineteenth century. It began changing during the first half of the twentieth century due to the introduction of western education and most of all, Christianity. Nadleeh since then has moved underground."22

Wesley, who spent the first thirty years of life on the Eastern Navajo reservation, wrote that in his initial fieldwork research he identified four categories of sex: female/woman, male/man, female/man, and male /woman. "Where I began to identify gender on a continuum—meaning placing female at one end and male on the other end—I placed forty-nine different gender identifications in between. This was derived at one sitting, not from carrying out a full and comprehensive fieldwork research. This number derived from my own understanding of gender within the Navajo cosmology. "

I have faced so much persecution because of my gender expression that I also wanted to hear about the experiences of someone who grew up as a "masculinegirl" in traditional Native life. I thought of Spotted Eagle, who I had met in Manitoba, and who lives in Georgia. Walking down an urban street, Spotted Eagle's gender expression, as well as her nationality, could make her the target of harassmentand violence. But she is White Mountain Apache, and I knew she had grown up withher own traditions on the reservation. How was she treated?

"I was born in 1945," Spotted Eagle told me. "I grew up totally accepted. I knewfrom birth, and everyone around me knew I was Two-Spirited. I was honored. I wasa special creation; I was given certain gifts because of that, teachings to share withmy people and healings. But that changed—not in my generation, but in generations to follow."

There were no distinct pronouns in her ancient language, she said. "There werethree variations: the way the women spoke, the way the men spoke, and the cere-monial language." Which way of speaking did she use? "I spoke all three. So did thetwo older Two-Spirit people on my reservation."24

Spotted Eagle explained that the White Mountain Apache nation was small and isolated, and so had been less affected early on by colonial culture. As a result, theU.S. government didn't set up the mission school system on the White Mountain reservation until the late 1930s or early 1940s. Spotted Eagle said she experiencedher first taste of bigotry as a Two-Spirit in those schools. "I was taken out of the mis-sion school with the help of my people and sent away to live with an aunt off reser-vation, so I didn't get totally abused by Christianity. I have some very horriblememories of the short time I was there."25

"But as far as my own people," Spotted Eagle continued, "we were a matriarchy,and have been through our history. Women are in a different position in a matri-archy than they are out here. It's not that we have more power or more privilegethan anyone else, it's just a more balanced way to be. Being a woman was a plus andbeing Two-Spirit was even better. I didn't really have any negative thoughts aboutbeing Two-Spirit until I left the reservation."26

Spotted Eagle told me that as a young adult she married. "My husband was alsoTwo-Spirit and we had children. We lived in a rather peculiar way according to stan-dards out here. Of course it was very normal for us. We faced a lot of violence, butwe learned to cope with it and go on."27

Spotted Eagle's husband died many years ago. Today her partner is a woman.Her three children are grown. "Two of them are Two-Spirit." she said proudly."We're all very close."28

I asked her where she found her strength and pride. "It was given to me by the people around me to maintain," she explained. "If your whole life is connected spiritually, then you learn that self-pride—the image of self—is connected with everythingelse. That becomes part of who you are and you carry that wherever you are.

What was responsible for the imposition of the present-dax rigid sex gender system in North America? It is not correct to simply blame patriarchy, Chrystos stressed to me."The real word is 'colonization' and what it has done to the world. Patriarchy is a tool of colonization and exploitation of people and their lands for wealthy white people."3

"The Two-Spirit tradition was suppressed," she explained, "l ike all Name spirituality, it underwent a tremendous time of suppression. So there's gaps. Bui we've continued on with our spiritual traditions. We are still attached to this land and the place of our ancestors and managed to protect our spiritual traditions and our languages. We have always been at war. Despite everything—incredible onslaughts that even continue now—we have continued and we have survived."31

Like a gift presented at a traditional give away, Native people have patiently given me a greater understanding of the diverse cultures that existed in the Western hemisphere before colonization.

But why did many Native cultures honor sex/gender diversity, while European colonialists were hell-bent on wiping it out? And how did the Europeans immediately recognize Two-Spiritedness? Were there similar expressions in European societies?

Thinking back to my sketchy high-school education, I could only remember one person in Europe whose gender expression had made history.

They Called Her "Hommasse"

Didn't Joan of Arc wear men's clothes?" I asked a friend over coffee in 1975. She had a graduate degree in history; I had barely squeaked through high school. I waited for her answer with great anticipation, but she dismissed my question with a wave of her hand. "It was just armor." She seemed so sure, but I couldn't let my question go. Joan of Arc was the only person associated with cross-dressing in history I'd grown up hearing about.

I thought a great deal about my friend's answer. Was the story of Joan of Arc dressing in men's clothing merely legend? Was wearing armor significant? If a society strictly mandates only men can be warriors, isn't a woman military leader dressed in armor an example of cross-gendered expression?

All I knew about the feudal period in which Joan ofArc lived was that lords owned vast tracts of land and lived off the forced agricultural labor of peasants. But I made the decision to study Joan of Arc's life, and her story opened another important window on trans history for me.

In school, we'd quickly glossed over the facts of Joan of Arc's life. So I hadn't realized that in 1431, when she was nineteen years old, Joan of Arc was burned at the stake by the Inquisition of the Catholic Church because she refused to stop dressing in garb traditionally worn by men. And no one had ever taught me that her peasant followers considered Joan of Arc—and her clothing—sacred.

I discovered that more than ten thousand books have been written about Joan of Arc's extraordinary life. She was an illiterate daughter of the peasant class, who as a teenager demonstrated a brilliant military leadership that helped birth the nation-state of France. What impressed me the most, however, was her courage in defending her right to self-expression. Yet I was frustrated at how many texts analyzed Joan of Arc solely as an individual, removed from the dynamics of a tumultuous period and place. I was particularly interested in understanding the social soil in which this remarkable person was rooted.

Joan of Arc was born in Domremy, in the province of Lorraine, around 1412. Only half a century before her birth, the bubonic plague had torn the fabric of the feudal order. One-third of the population of Europe was wiped out, whole provinces were depopulated. Peasant rebellions were shaking the very foundations of European feudalism.

At the time, France was gripped by the Hundred Years War. French peasants suffered plunder and violence at the hands of the marauding English occupation armies. The immediate problem for the peasantry was how to oust the English army, a task the French nobility had been unable to accomplish.

Joan of Arc emerged as a leader during this period of powerful social earth-quakes. In 1429, dressed in men's clothing, this confident seventeen year old presented herself and a group of her followers at the court of Prince Charles, heir to the French throne. In the context of feudal life, in which religion permeated everything, Joan asserted that her mission, motivation, and mode of dress were directed by God. She declared her goal: to forge an army of peasants to drive out the English. Prince Charles placed her at the head of a ten-thousand-strong peasant army.

The rest is history that has been replayed again and again in text and film. Unable to read or write, Joan of Arc dictated a letter to the King of England and the Duke of Bedford, leader of the English occupying army in Orleans, demanding they leave French soil, vowing, "[I]f you do not do so, you will remember it by reason of your great sufferings." 1

On April 28, 1429, Joan led a march on Orleans. The next day, she entered the city at the head of her peasant army. By May 8, the English were routed. Over the next months, she further proved her genius as a military strategist and her ability to inspire the rank-and-file soldiers by liberating other French villages and towns and forcing the English to retreat.

Joan persuaded Charles to go to Rheims to receive the crown. It was an arduous trip—long and dangerous—through territory still occupied by English troops. Although her army was exhausted and famished along the way, they forced the English to yield still more turf. As Charles was crowned King of France, Joan stood beside him, holding her combat banner. The French nation-state, soon to be fully liberated from occupation, was born.

On May 23, 1430, Joan was captured by the Burgundians, French allies of the English feudal lords. The Burgundians referred to her as hommasse, a slur meaning "man-woman," or masculine woman.2 Had she been a knight or nobleman, King Charles would have offered a ransom for Joan's freedom, since ransom was the customary method of freeing knights and nobility captured in battle. Even the sums were fixed—one could ransom a royal prince for 10,000 livres of gold, or 61,125 francs. 3 Once ransom was offered, it had to be accepted. But Joan's position as military leader of a popular peasant movement threatened the very French ruling class she helped lift to power. The French nobility didn't offer a single franc for her release. What an arrogant betrayal. How anxious they must have been to be rid of her.

The English urged the Catholic Church to condemn Joan for cross-dressing. The king of England, Henry VI, wrote to the infamous Inquisitor Pierre Cauchon, the Bishop of Beauvais: "It is sufficiently notorious and well-known that for some time past a woman calling herself Jeanne the Pucelle (the Maid) , leaving off the dress and clothing of the feminine sex, a thing contrary to divine law and abominable before God, and forbidden by all laws, wore clothing and armour such as is worn by men." Buried beneath this outrage against Joan's cross-dressing was a powerful class bias. It was an affront to nobility for a peasant to wear armor and ride a fine horse. This offense was later elaborated in one of the charges against Joan that claimed she dressed "in rich and sumptuous habits, precious stuffs and cloth of gold and furs."4

The Burgundians sold Joan of Arc to the English, who turned her over to the Inquisition in November 1430. Joan was held in a civil prison in Rouen, France, an English stronghold at that time. She was reportedlv guarded by English male soldiers who slept in her cell, in violation of the Church's own rules. She was shackled in a small iron cage "in which she was kept standing, chained by her neck, her hands and her feet," according to the locksmith who built the cage.5

Joan's trial began in Rouen on Januan 9, 1431. The Grand Inquisitors condemned Joan for cross-dressing and accused her of being raised a pagan. Church leaders had long charged that the district of her birth, Lorraine, was a hotbed of paganism and witchcraft. One of the principal accusations against Joan was that she associated with "fairies, a charge leveled by the Church in their war against paganism. (Which, incidentally,derives from the Latin paganus, meaning ruraldweller or peasant.) The Church was waging war against peasants who resisted patriarchal theology and still held onto some of the old pre-Christian religious beliefs and matrilineal traditions. This was true of peasants in the area of Lorraine, even in the period of Joan's lifetime. For instance, the custom of giving children the mother's surname, not the father's, still survived there. 7

Scapegoating Joan of Arc and the area of her birth fueled the Church's reactionary campaign. And the more Joan of Arc was idolized by her followers, the more she posed a threat to the Church's religious rule. Article III of the Articles of Accusations stated this clearly: "Item, the said Joan by her inventions has seduced the Catholic people, many in her presence adored her as a saint...even more, they declared her the greatest of all the saints after the holy Virgin "8 No wonder the Church fathers feared her!

On April 2, 1431, the Inquisition dropped the charges of witchcraft against Joan, because they were too hard to prove. Instead, they denounced her for asserting that her cross-dressing was a religious duty compelled by voices she heard in visions, and for maintaining that these voices were a higher authority than the Church. Many historians and academicians view Joan of Arc's wearing men's clothing as inconsequential. Yet the core of the charges against Joan focused on her cross-dressing, the crime for which she ultimately was executed. However, the following quote from the verbatim court proceedings of her interrogation reveals it wasn't just Joan of Arc cross-dressing that enraged her judges, but her cross-gendered expression as a whole:

You have said that, by God's command, you have continually worn man's dress, wearing the short robe, doublet, and hose attached by points; that you have also worn your hair short, cut en rond above your ears, with nothing left that could show you to be a woman; and that on many occasions you received the Body of our Lord dressed in this fashion, although you have been frequently admonished to leave it off, which you have refused to do, saying that you would rather die than leave it off, save by God's command. And you said further that if you were still so dressed and with the king and those of his party, it would be one of the greatest blessings for the kingdom of France; and you have said that not for anything would you take an oath not to wear this dress or carry arms; and concerning all these matters you have said that you did well, and obediently to God's command. As for these points, the clerks say that you blaspheme God in His sacraments; that you transgress divine law, the Holy Scriptures and the canon law; you hold the Faith doubtfully and wrongly; you boast vainly; you are suspect of idolatry; and you condemn yourself in being unwilling to wear the customary clothing of your sex, and following the custom of the Gentiles and the Heathen.9

Even though she knew her defiance meant she was considered damned, Joan's testimony in her own defense revealed how deeply her cross-dressing was rooted in her identity. "For nothing in the world," she declared, "will I swear not to arm myself and put on a man's dress."

But by April 24, 1431, Joan's judges claimed she had recanted, after having been taken on a tour of the torture chamber, and brought to a cemetery where she was shown a scaffold that her tormentors said awaited her if she did not repent. Joan allegedly accused herself of wearing clothing that violated natural decency, and agreed to submit to the Church's authority and wear women's apparel. She was "mercifully" sentenced to life in prison on bread and water—in women's dress.

However, since Joan could neither read nor write, did she know the exact details of what she was signing? This is an important question, because cross-dressing was not a capital offense at that time. And the Inquisition did not have the power to turn a heretic over to the secular state for execution. But the church judges were empowered to condemn a relapsed heretic. 11

Did Pierre Cauchon, the Inquisitor, trick Joan into making her mark on a document that signed away more than she'd realized? Perhaps Cauchon later revealed the exact contents of the phony confession in hopes she would renege. Or were parchments switched? Witnesses described Joan making her mark on a short declaration; the confession in the court records is very long. 12

Whatever the case, Joan recanted the alleged abjuration within days and resumed wearing men's clothes. Her judges asked her why she had done so. when putting on male garb meant certain death. According to the court record she said she had done so "of her own will. And that nobody had forced her to do so. And that she preferred man's dress to woman's." Joan told the judges she "had never intended to take an oath not to take man's dress again."13 The Inquisition sentenced her to death for resuming male dress, saying "time and again you have relapsed, as a dog that returns to its vomit. . . ." H

Joan of Arc was burned alive at the stake on May 30, 1 431, in Rouen. She was nineteen years old. The depth of her enemies' hatred toward her transgender expression was demonstrated at her execution, when they extinguished the flames in order to prove she was a "real" woman. After her clothing was burned away and Joan was presumed dead, one observer wrote, "Then the fire was raked back and her naked body shown to all the people and all the secrets that could or should belong to a woman, to take away any doubts from people's minds."15

Joan of Arc suffered the excruciating pain of being burned alive rather than renounce her identity. I know the kind of seething hatred that resulted in her murder—I've faced it. But I wish I'd been taught the truth about her life and her courage when I was a frightened, confused trans youth. What an inspirational role model-a brilliant transgender peasant teenager leading an army of laborers into battle.

But one aspect of the information I'd gathered left me puzzled. Why did the feudal ruling class and the Church abhor her transgender so violently, while the peasants considered it so sacred? There's no question how much Joan of Arc was honored by the peasantry. Even the Church admitted that the peasants considered her the greatest of all the saints after the holy Virgin.

It's also clear that Joan of Arc's cross-dressing was central to that reverence. Gay historian Arthur Evans noted that before Joan was captured by the Burgundians: "[W]henever she appeared in public she was worshipped like a deity by the peasants. The peasants believed that she had the power to heal, and many would flock around her to touch part of her body or her clothing (which was men's clothing). Subsequently her armor was kept on display at the Church of St. Denis, where it was worshipped." 16

According to Professor Margaret A. Murray, "The enormous importance as to the wearing of the male costume is emphasized by the fact that as soon as it was known in Rouen that Joan was again dressed as a man the inhabitants crowded into the castle courtyard to see her, to the great indignation of the English soldiers who promptly drove them out with hard words and threats of hard blows."17

I could not answer, yet, why the peasants venerated Joan of Arc's cross-dressing. But I thought back to a clue buried in the condemnation of Joan by her judges. What did they mean when they charged that her cross-dressing was "following the custom of the Gentiles and the Heathen?" What custom? Were there other examples of cross-dressing among the peasantry? Did the peasants consider transgender itself to be sacred? If so, why?

I had no idea where to find the answers to these questions.

Part 2

Our Sacred Past

I remember riding a bus in the middle of the night during a bitter snowstorm in the early months of 1976. was traveling, along with many other activists, to a political conference in Chicago. Unable to sleep, I read a xeroxed copy of a Workers World pamphlet so new the typeset copies weren't yet back from the printers. 1 That landmark pamphlet—a Marxist examination of the roots of lesbian and gay oppression—was authored by Bob McCubbin, a gay man I worked with in our New York City branch. I had known Bob was working on that history, but I'd had no concept of how his research and analysis would impact on my life.

I found myself in those pages. For the first time since I'd acknowledged my own sexual desire to myself, I felt released from a layer of unexamined shame. Bob presented an overview of human history so I could see that same-sex love had always been part of the spectrum of human sexuality. He provided examples of early communal societies that honored all forms of human love and affection. Bob analyzed how and why the division of society into classes led to increasingly hostile attitudes by rulers towards same-sex love. And to my surprise, he included examples of acceptance of transgender in cooperative societies.

As I shivered next to a bus window thick with ice, I cried with relief. I realized how important it was for me to know I had a place in history, that I was part of the human race.

As I read and reread that pamphlet in the years that followed, I saw that I could also approach trans history from a materialist point of view. So I went back and took another look at the charge by Joan's Inquisitors that she followed "the custom of the Gentiles and the Heathen." In my family, gentiles meant non-Jews. But I remembered Engels's use of the term gens and it occurred to me that the French clerics were referring to free farming communities still organized into gens, the family unit of cooperative matrilineal societies.

I wanted to go back further, to dig around for prehistoric evidence of transgender in communal societies in Europe. But how could I? Although these early communities were cooperative up until about 4000 B.C.E.*—estimated to be the end of the Stone Age, or the Neolithic period—these ancient farmers and hunters left no written records.

So I combed through books, periodicals, and news clippings devoted to the history of Europe, Africa, Latin America, the Middle East, and Asia. I searched for the earliest written records of any forms of trans expression. Much to my surprise, I found a lot of information.

For example, I discovered abundant evidence of male-to-female transsexual women priestesses who played an important role in the worship of the Great Mother. Extensive research by scholars has revealed that this goddess, not male gods, was venerated throughout the Middle East, Northern Africa, Europe and western Asia.

The Great Mother was emblematic of pre-class communalism. Today, many scholars describe her as a female goddess. But perhaps those who revered her saw this divinity as more complex. While it's impossible today to interpret precisely how people who lived millennia ago viewed this goddess, Roman historian Plutarch described the Great Mother as an intersexual (hermaphroditic) deity in whom the sexes had not yet been split.

The Great Mother's transsexual priestesses followed an ancient and sacred path of rituals that included castration. These transsexual priestesses continued to serve the Great Mother in societies in which class divisions were just developing. They are documented in Mesopotamian temple records from the middle of the third millennium B.C.E., and are also found in Assyrian, Akkadian, and Babylonian records.

Many Mediterranean, Middle Eastern, and Near Eastern goddesses were served by transsexual priestesses, including the Syrian Astarte and Dea Syria at Hierapolis, Artemis, Atargatis, Ashtoreth or Ishtar, Hecate at Laguire, and Artemis (Diana) at Ephesus. Statues of Diana were often represented draped with a necklace made of the testicles of her priestesses.4

Transsexual women priestesses known as gallae were found in such large numbers in Anatolia, an area which today is part of Turkey, that some classical texts report as many as five thousand in some cities. 5 The gallae served the Great Mother, known to the Phrygians as Cybele, whose worship is believed to date back to the Stone Age.6

Was the sacred service of transsexual priestesses a practice rooted in communal matrilineal societies? Or was it an example of men, living under patriarchy, castrating themselves in order to wrest this position from women? Not all researchers and historians agree.

For example, historian David F. Greenberg's findings seem to support the first position. He concludes that evidence of trans shamans, "among peoples whose later ways of life have been very diverse, suggests that the role does date back to the late Paleolithic (if not earlier)."7

Feminist researcher Merlin Stone is a prominent spokesperson for the latter argument. She wrote about the transition in Mediterranean and Middle Eastern cultures from communal to early classdivided societies. Stone argues: "It seems quite possible that as men began to gain power, even within the religion of the Goddess, they replaced priestesses. They may have initially gained this right by identifying with and imitating the castrated state of the son/lover; or in an attempt to imitate the female clergy, which originally held the power, they may have tried to rid themselves of their maleness by adopting the ritual of castration and the wearing of women's clothing."8

Stone's argument rests on a biological determinist definition of these transsexual priestesses as men. But how could priestesses who had "rid themselves of their maleness" expect to curry much favor with the new wealthy men who so valued males over females? Besides being bereft of "maleness," these priestesses continued the practice of matrilineal goddess worship that rivaled the patriarchal religions of new male-dominated ruling classes.

And what about the statement that the female clergy "originally held the power"? From where did women's "power" derive in cooperative societies? Was it based on holding the spiritual reins?

Anthropologists have reconstructed patterns of life in Stone Age Europe, in much the same way as paleontologists have rebuilt models of dinosaurs. The Stone Age was a span of human development before the use of metals, when tools and hunting implements were fashioned from stone. Humans lived by hunting and food gathering; group labor was cooperative.

In these early societies, most men hunted while most women developed a division of labor in large centers of production and shared the responsibility of child-care. Women didn't rule over men, the way men dominate women in a patriarchal society. There were no signs of pharaohs and emperors, queens or presidents, who lived in luxury while others toiled in squalor. Leadership could not be coerced or bought, so it had to be earned through group respect.

The family structure of these societies was matrilineal and matrilocal—meaning women headed the family groupings and the collective homes. Blood descent and inheritance were traced through women.In these Stone Age societies, women were so respected that anthropologist Jacquetta Hawkes concluded, "Indeed, it is tempting to be convinced that the earliest Neolithic societies throughout their range in time and space gave woman the highest status she has ever known."9

But did these cooperative societies only have room for two sexes, fixed at birth? It has become common for social scientists to conclude that the earliest human division of labor between women and men in communal societies formed the basis for modern sex and gender boundaries. But the more I studied, the more I believed that the assumption that every society, in every corner of the world, in every period of human history, recognized only men and women as two immutable social categories is a modern Western conclusion. It's time to take another look at what we've long believed was an ancient division of labor between only two sexes.

Our earliest ancestors do not appear to have been biological determinists. There are societies all over the world that allowed for more than two sexes, as well as respecting the right of individuals to reassign their sex. And transsexuality, transgender, intersexuality, and bigender appear as themes in creation stories, legends, parables, and oral history.

As I've already documented, many Native nations on the North American continent made room for more than two sexes, and there appeared to have been a fluidity between them. Reports by military expeditions, missionaries, ethnographers, anthropologists, explorers, and other harbingers of colonialism cited numerous forms of sex-change, transgender, and intersexuality in matrilineal societies—societies where men were not in a dominant position. In these accounts—no matter how racist or angrily distorted by the colonial narrative voice—it is clear that transsexual priestesses and other trans spiritual leaders, or medicine people, have existed in many ancient cultures.

It's not possible in many of the following examples to make a distinction between transsexual, transgender, bigender, or mixed gender expression. However, trans spiritual leaders played a role in far-flung cultures all over the world.