Provisional Military Government of Socialist Ethiopia (1974–1987)

| Provisional Military Government of Socialist Ethiopia የኅብረተሰብአዊት ኢትዮጵያ ጊዜያዊ ወታደራዊ መንግሥት | |

|---|---|

| 1974–1987 | |

Anthem: ኢትዮጵያ ኢትዮጵያ ኢትዮጵያ ቅደሚ (English: Ethiopia, Ethiopia, Ethiopia be first" | |

| |

| Capital and largest city | Addis Ababa |

| Official languages | Amharic |

| Dominant mode of production | Socialism |

| Government | Marxist–Leninist military junta |

• Head of State (1974) | Aman Adom |

• Head of State (1974-1974) | Mengistu Haile Mariam |

• Head of State (1974-1977) | Tafari Benti |

• Head of State (1977-1987) | Mengistu Haile Mariam |

| History | |

• Established | 1974 |

• Dissolution | 1987 |

| Area | |

• Total | 1,221,900 km² |

| Population | |

• 1987 estimate | 46,706,229 |

The Provisional Military Government of Socialist Ethiopia, also known as the Derg, was a socialist military junta that ruled Ethiopia between the Ethiopian revolution of 1974 and the establishment of a civilian government in 1987.

History

Revolution

See main article: Ethiopian revolution

It began on the 12 January 1974, when Ethiopian soldiers began a rebellion in Negele Borana, with the protests continuing into February 1974. People from different occupations, starting from junior army officers, students and teachers, and taxi drivers joined a strike to demand human rights, social change, agrarian reforms, price controls, free schooling, and releasing political prisoners, and labor unions demanded a fixation of wages in accordance with price indexes, as well as pensions for workers, etc.

In June 1974, a group of army officers established the Coordinating Committee of the Armed Forces, later branding itself as the Derg, which aimed to topple Haile Selassie cabinet under Prime Minister Endelkachew Makonnen. By September of that year, the Derg began detaining Endalkachew's closest advisors, dissolved the Crown Council and Imperial Court and disbanded the emperor's military staff. The Ethiopian Revolution ended with the 12 September coup d'état of Haile Selassie by the Coordinating Committee of the Armed Forces.

In September 1974, the absolute monarchy of Ethiopia led by Emperor Haile Selassie was overthrown. The revolution was supported by students, teachers, trade unions, and the military.[1]

Power struggles and consolidation

Nationalisation, land reform and the Zemecha Campaign

The Derg issued its ten-point-programm on the 20th December 1974, which was its first written attempt to formulate policy:

- Ethiopia shall remain a united country, without ethnic, religious, linguistic and cultural differences.

- Ethiopia wishes to see the setting up of an economic, cultural and social community with Kenya, Sudan and Somalia.

- The slogan Ityopya Tikdem (Amharic for Ethiopia first, sometimes in its more complete Yeminim dem, Ityopya Tikdem, Amharic for Without Blood, Ethiopia first) of the Ethiopian revolution is to be based on a specifically Ethiopian socialism.

- Every regional administration and every village shall manage its own resources and be self-sufficient .

- A great political party based on the revolutionary philosophy of Ityopya Tikdem shall be constituted on a nationalist and socialist basis.

- The entire economy shall be in the hands of the state. All assets existing in Ethiopia are by right the property of the Ethiopian people. Only a limited number of businesses will remain private if they are deemedto be of public utility.

- The right to own land shall be restricted to those who work the land.

- Industry will be managed by the state. Some private enterprises deemed to be of public utility will be left in private hands until the state considers it preferable to nationalize them.

- The family, which will be the fundamental basis of Ethiopian society, will be protected against all foreign influences, vices and defects.

- Ethiopia's existing foreign policy will be essentially maintained. The new regime will however endeavour to strengthen good-neighbourly relations with all neighbouring countries.[2]

This was the primary formulation of the political programme of the Derg until the Programme of the National Democratic Revolution in 1976.[2] The shortcomings and problems with this early policy formulation are described by Christopher Clapham as follows:

"The first article, in simply denying the existence of ethnic andrelated differences, obscured the conflict between an assimilationist nationalism (in which differences would be abolished) and the recognition of separate 'nationalities' on an equal basis, which would underlie the wholeproblem of national integration. The conservative provisions on foreign policy were to prove incompatible with the international implications of revolution, while in the management of the economy, the emphasis on the state was at odds with the references to regional autonomy and the idea of land to the tiller. In the event, neither of these last two principles was implemented , while the party , with which many of these contradictions were bound up, did not come into existence for a further ten years."[2]

In April 1976, the Derg released the National Democratic Revolution Program, which included land reform, nationalization of industries, and reorganization of unions.[3]

Nationalisation and urban reform

Land Reform (1975–1978)

The necessity for rural development is illustrated by the mentioning of some statistics of Ethiopia at the time: 92% of the people generate 60-65% of the GDP and 90% of the exports through agriculture. Subsistence peasant families constitute 86% of the population, and their production accounts for 45-50% of the GDP at the time.[4] Ethiopian agriculture prior to the Revolution was regarded by many to operate under its potential, given the countries large size, relatively low population density, general fertility, sufficient rainfall (at the time), climate and elevation variations allowing for cropping diversitification and 22.5 million peasants working only 7,9% of the total land. The 1973 famine in Wollo evidenced the previous governments indifference in utilising that potential.[4] Additionally, less than 1% of the population owned more than 70% of the arable. The royal family and landed aristocracy owned between 50-60% of arable land, leaving over 50% of the rural population as tenant-farmers.[5] The church is estimated to have possessed 20% of all arable land and 5% of all Ethiopian land, from which it derived most of its income.[6]

The legal framework of the land reform was provided by a series of decrees, or "proclamations" of the Provisional Military Administrative Council (PMAC), . These proclamations, issued between 4 March 1975 and 17 September 1977, form a coherent whole.[7](There were more proclamations regarding Rural Land, at least until 1982, but these had a minor effect on the groundwork being laid ealier)[8]. Land reform was not conceived simply as a matter of breaking up large estates, but above all as the problem of creating a new political and social organization in the countryside to defeat the landlords and allow the peasants to control their land and their affairs.[7] These proclamations are, in order:

- Proclamation No.31 of 1975 ("A Proclamation to Provide for the Public Ownership of Rural Lands")

- Proclamation No. 71 of 1975 ("Peasant Associations Organization and Consolidation Proclamation.")

- Rural Land Fee and Agricultural Activities Income Tax Proclamation[7]

- Proclamation No. 130. Sept. 1977 ("A Proclamation on Formation of nation-wide Peasant Associations")[8]

- Peasant Associations Consolidation Proclamation No. 223/1982

Proclamation No.31 reads in its preamble, proclaiming the wide- ranging effects and the reasoning for the proclamation:

"WHEREAS, in countries like Ethiopia where the economy is agricultural a person's right, honour, status and standard of living is determined by his relation to the land;(...) several thousand gashas of land have been grabbed from the masses by an insignificant number of feudal lords and their families as a result of which the Ethiopian masses have been forced to live under conditions of serfdom; (...) it is essential to fundamentally alter the existing agrarian relations so that the Ethiopian peasant masses which have paid so much in sweat as in blood to maintain an extravagant feudal class may be liberated from age-old feudal oppression, injustice, poverty, and disease, and in order to lay the basis upon which all Ethiopians may henceforth live in equality, freedom, and fraternity; (...) the development of Ethiopia of the future can be assured not by permitting the exploitation of the many by the few as is now the case, but only by instituting basic change in agrarian relations which would lay the basis upon which, through work by cooperation, the development of one becomes the development of all; (...) in order to increase agricultural production and to make the tiller the owner of the fruits of his labour, it is necessary to release the productive forces of the rural economy by liquidating the feudal system under which the nobility, aristocracy and a small number of other persons with adequate means of livelihood have prospered by the toil and sweat of the masses; (...) it is necessary to provide work for all rural people; it is necessary to distribute land, increase rural income, and thereby lay the basis for the expansion of industry and the growth of the economy by providing for the participation of the peasantry in the national market; (...) it is essential to abolish the feudal system in order to release for industry the human labour suppressed within such system; (..) it is necessary to narrow the gap in rural wealth and income" [9]

All land was declared the "collective property of the Ethiopian people." Landlords would receive no payment for their land (but there were promises to compensate for movable properties and permanent improvements previously made on the land[10]). Any person willing to cultivate the land would be allotted the use of a plot, up to a maximum of ten hectares for each farming family. Private individuals would not be allowed to hire agricultural workers.

To prevent the peasants from becoming de facto small-holders, each cultivating his fields in isolation from the others, Peasant Associations would be created throughout the country, each covering an area of at least eight hundred hectares. Membership in the associations was open to all farmers, except those who had previously owned more than ten hectares of land.

These peasant associations were responsible for implementing the land reform and distributing the land equally among their members[7], considering both the size of the family and the quality of the soil. They were additionally empowered to supervise land-use regulations, administer public property, establish judicial committees, service co-operatives and an elementary form of producer's cooperatives, and promote socio-economic infrastructure and villigization programs.[10] They would elect their own officials and adjudicate disputes arising from the distribution of land among their members. [7]Within the peasant associations, the peasants elected a chairperson, secretary, a treasurer and two assistants by show of hands. A number of peasant associations permitted farmers to work the land they possessed, but provided land to landless peasants. Some were more radical and completed land distribution within two months.[10] However, 79.7% of the members of judicial committees were illiterate, and the position was sometimes regarded as nominal, whereas few peasant associations held internal regulations in written form. The responsibility for forming peasant associations rested with the Ministry of Agriculture and the Ministry of Interior.

The proclamation treated the pattern of transfer of land differently depending on three tenure types: the northern rist tenure, private ownership tenure (which was most affected by the Proclamation in the way illustrated above) and tenure in nomadic areas. In the north, the peasant associations were primarily tasked with organizing producers cooperatives, without forseeing the need for land distribution. In the nomadic regions, the peasant associations were tasked to induce the cooperative use of water and grazing rights. Nomadic people were entitled to possess their grazing lands, except those that were used for mining or large-scale national agricultural projects. Payments made by nomadic people to traditional elites (called balabat,[6] not to be confused with the mekwanint of equal status) were nullified.[10]

The first step in the direction of strengthening the autonomy of the peasant associations was Proclamation No. 71 of 1975, called "Peasant Associations Organization and Consolidation Proclamation."

This measure accomplished three tasks:

- it gave the peasant associations a legal personality;

- it outlined a path of growth for the peasant associations beyond land distribution, allowing them to create cooperatives and even to set up their own armed defense squads of peasant militias; and

- it strengthened the higher level peasant associations, integrating them into the regional administration through the creation of "Revolutionary Administration and Development Committees."[7]

This was intended to allow peasant associations to borrow collectively under the governments loan plan in order to purchase seed and fertilizers, or to become members of a cooperative, i.e. fostering the conditions away from individual exploitation of the land and towards agricultural communes. It also expanded the political roles of the peasant associations:

- to enable peasants to secure and safeguard their political, economic and social rights;

- to enable the peasantry to administer itself;

- to enable the peasantry to participate in the struggle against feudalism and imperialism by building its consciousness in line with Hebrettesebawinet (Ethiopian socialism);

- to establish cooperative societies, women's associations, peasant defense squads and any other associations that may be necessary for the fulfillment of its goals and aims;

- to enable the peasantry to work collectively and to speed up social development by improving the quality of the instruments of production and the level of productivity;

- to sue and be sued;

- to issue and implement its internal regulations in order to achieve its goals and aims.[7]

It is important to note that the decision to arm the peasants needs to be seen in the context of the severe criticism the Derg was subjected to by other radicals for failing to do so. Sometimes, the arming of peasants was done out of the peasants or Zemecha-Campaigners own initiative prior to the proclamation, with the formation of "Red Guards" especially in southern Ethiopia. These then often went about disarming the landlords. [10] By 1977, 98.8% of peasant associations had a defense squad, with memberships between 6-25 peasants.[10]

The now formed peasant associations would be divided into two categories, referred to as "service cooperative societies" (consiting of at least two peasant associations) and "agricultural producers' cooperative societies", with the vision of a gradual transformation from service cooperatives to advanced prducers cooperatives[10]

The goals of the service cooperatives were strictly economic, namely to provide their members with extension services, loans, storage facilities, and marketing services. In addition they were to encourage savings, distribute basic consumer goods, and establish flour mills and small cottage industries. The agricultural producers' cooperatives, on the other hand, had above all political goals. They would assume control over the "instruments of production" of their members, and gradually assume ownership; they would "divide members into working groups to enable them to work collectively," and their officials would be drawn only from among poor and middle peasants. Among their main objectives was "to struggle for the gradual abolition of exploitation from the rural areas."[7] The Elementary produces cooperatives 75% of land was to be owned collectively, thogh farm impliments and livestock could remain private, whereas income was to be devided "from each according to his ability to each according to his contribution", barring special reserves, funds for welfare costs etc. Peasant cooperatives had a executive commitee, an auditing committee to oversee the executive committee and to report the financial status of a cooperative to the general assembly. [10] By 1978, 343 service and 21 producers cooperatives existed in Ethiopia (covering 9% of all Peasants Associations).[10]

The "Rural Land Fee and Agricultural Activities Income Tax Proclamation." of January 1976 etablished agricultural income tax. The law begins with a preamble declaring it the national duty of every peasant given land use rights and the opportunity to earn income to contribute part of his earnings to finance development programs adopted by the government for the benefit of the rural populace. The preamble specifically notes the need for programs in agricultural research and extension, road construction, communications facilities, and market improvement.Land use fees and agricultural income taxes are to be collected either by the peasant associations, by a person appointed by the Ministry of Finance, or by the local woreda tax office of that ministry.[6]

Since 1977 (Proclamation No.130), Peasant associations were to be organized into a five-level structure, with the lowest unit being the local peasant association and the highest governing body the All-Ethiopia Peasant Association (AEPA). Members of the AEPA are elected by the general assembles of the respective regional (kifle-hagar) Peasants Associations.[8] In between, the woreda, awrajja and kifle-hagar peasant associations would coordinate local associations and set up judicial commitees.[10] Furthermore, each peasant association would elect representatives to a woreda peasant association, and these in turn would elect their representatives to the awrajja peasant association.[7]

By late 1975, 19,000 peasant associations had been established, with a membership of about 4 million peasant households. In 1976, this reached 24,707 peasant assocations with 6.8 million households, and in 1977-1978 there were 28,583 peasant associations with a membership of 7.3 million households.[10]

Interpretation. Limitations and Criticism of the Land Reform and its Implementation

Zemecha-Campaign (1974-1976)

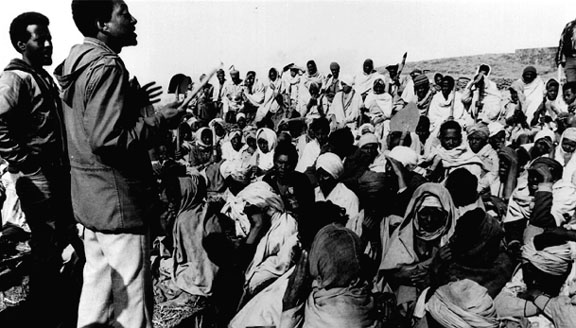

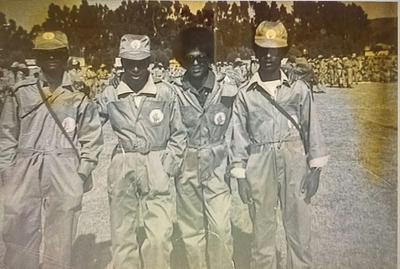

Concurrently and in preparation to the Ethiopian Land Reform, in early 1975, the Derg created the Ediget Behibret Zemecha (Development through Cooperation Campaign), which encompassed the closure of the Addis Abeba University in the beginning of 1975, so that 6,000 university students and 50,000 secondary school students could be sent to 437 places in the countryside. This was intended to teach and politicize the peasant, and help develop the rural masses. In the course of the campaign, university students taught peasants about civil rights, land ownership and hygiene, created awareness of land redistribution, and participated in the formation of peasant associations, bringing literacy and building schools, clinics and latrines. The AAU was reopened in the 1976/1977 academic year. [11]

Determining the correct approach to implement the Zemecha was difficult. To this end, Zemecha leaders proposed the following remedies:

- Campaigners were to go only were they knew the roads, cultural traits, lifestyle and languages of the people

- Dissemination of information was to take place at market-places, schools, churches, mosques, religious centers and official gathering places

- Priority was to be given to educating local administrators, spiritual leaders, and influential residents. Speak the language local to the area without a translator[12]

Following advice was given to Zemecha-Campaigners (Amharic: Zemach):

- Speak in the local language without translator

- Do not claim the ability to complete a task when there is the slightest possibility that you could not

- Do not give empty promises

- Be honest and sincere

- Avoid opposing traditional culture, but if absolutely necessary to do so, apply the utmost care as not to arouse the people's ire

- Reject arrogance

- Be receptive towards peoples ideas, but if opposition is called for, make a thorough explanation

- Live like the people

- Do not shocase superiorty in public

- Speak cautiously and be a good listiner

- In oder to explain personal opinions, make use of clear and concise examples

- Show fratenal and filial concern

- Respect Individuals in Private Conversations

- Be Patient

- Think Before you Speak[12]

The Zemecha-Campaign played a major role in the initial phase of the formation of Peasant Associations. Prior to the Land Reform, students were already preparing the peasantry for the expected reform. The timing of the proclamation, at the start of the crop season of the region, and the need to preempt some social classes from organizing themselves to form resistance, necessitated a speady introduction of the Peasant Associations. Zemecha-Campaigners were also those who in the beginning registered those who met state criteria for memebership in the Peasant Associations outlined above.[13] After the students left, these their role was partially taken over by the officials of the political party the Derg had undertaken to create. This embryonic party was known as the Provisional Office for Mass Organizational Affairs (POMOA)[7], and existed between 1975-1979.

Successes

The Zemecha Campaign, via its Alphabetization Program, taught over 350,000 peasants how to read, write, and perform arithmetic in their vernacular language. Initially, six languages were selected for pedagogicial use: Amharic, Afaan Ormo, Tigrinya, Wolaitigna, Somali, Afarigna, Sidamigna and Hadiygna. Teaching material for the first five were completed early in the Zemecha campaign.[12] These 350,000 peasants were only thaught by 40% of the campaigners due to political disturbances. Comparing this to the previous governent (under Haile Selassie I), which had a literacy rate of 6%, a benchmark which has not been passed in about 60 years of political control, the results were commendable.[15]

The campaigners taught health education to a million people, built 155 schools and 296 clinics (more than 50% of Ethiopias total at the time), trained 1500 midwives, and increased the number of nurses by 40%. They additionally vaccinated 1,250,000 people against various diseases, planted 2,000,000 trees, and vaccinated over 300,000 cattle. Additionally, by late 1975, 6 million people were organized into 19,000 Peasant Associations and 3,700 woman's associations.[15] Additionally, many wells, roads, wooden bridges, meeting halls, latrines, health centres and market places were built, in addition to water pumps, water wheels, wind mills, and even medium range transistor radios, from locally-sourced materials. Total costs for this were 17 Million ETB (at the time 8.5 Million Dollars), one-third of the initially planned cost. [12]

Criticism and issues

116 Campaigners were killed. Sometimes, campaigners were sent to the wrong regions, and were therefore place before linguistic and cultural barriers. The campaigners backround, differing widely in age, exerience, ability and level of education, were not functionally classified. Some station chiefs were selected only on the basis of educational backround, rather than on organisatioal capacity.

There existed differences in the subjective and objective conditions in different parts of the country. E.g., the proclamation "Land to the tiller" did not carry the same significance for a Tigrean, Gondare or Gojame farmer, as land has been locally controlled for centuries (in contradistinction to the south which only were made part of the Ethiopian Empire through Menelik's conquests, the Agar Maqnat). [12]

This, in addition to the still relatively obscure class distinctions in the north, as strong blood relations tied the farmer to the feudal administrator, and the reforestation programmes, in the heavily eroded landscapes in the north, did not generate the dramatic short term effects that generated enthusiasm for the revolution as elsewhere. This also lead to the campaigners being viewed as outsiders or external threats. Major obstructions also emenated from the former local officials, counterrevolutionary members of the police force, and armed landords. The movement also was subject to sabotage, sometimes emenating from neighbouring countries.[12]

Some Zemecha participants were also unwilling to participate, rejecting to work as medical or agricultural personnel, leading to desertions (especially after the Zemecha was extended from the initial one year programme). In total, 69 stations were abandoned, and 6,502 students relocated due to political disturbances, whereas 14 stations composed of 1984 campaigners were closed down due to resistance from the campaigners themselves. A lack of ideological coherence among the students also led to a dissemination of often contradictory political messaging, and some students refused to learn from the masses.[12]

Opposition to the Derg and Ideological Struggles

Nej Shibir and Qey Shibir (White Terror and Red Terror)

Ogaden-War

Emergence of Ethnonationalist Groups and the Ethiopian Civil War

Formation of the Workers Party of Ethiopia

Famine of 1984-1986

Dissolution of the Derg

Ideology

Political structure

Economics and the Effects of Policies

Interpretations of the Legacy and Nature of the Derg

References

- ↑ Andargachew Tiruneh (1990). The Ethiopian Revolution (1974 to 1984). [PDF] PhD Thesis, London School of Economics.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Christopher Clapham (1988). Transformation and continuity in revolutionary Ethiopia (pp. 45-46). African Studies Series 61, Cambridge University Press. [LG]

- ↑ Patrick Gilkes (1982). Building Ethiopia's Revolutionary Party. [PDF] Middle East Research and Information Project.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Paul Brietzke (1976). Land Reform in Revolutionary Ethiopia (pp. 637-638). The Journal of Modern African Studies, 14,4, 637-660.

- ↑ Girma Kebbede (1987). State Capitalism and Development: The Case of Ethiopia (p. 4). The Journal of Developing Areas, Vol. 22, No. 1, 1-24.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 John M.Cohen and Peter. H. Koehn (1978). Rural and Urban Land Reform in Ethiopia (pp. 5-8). [PDF] African Law Studies, No 14/19/7, reprinted by LAND TENURE CENTER, University of Wisconsin-Madison, LTC Reprint No. 135.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 7.8 7.9 Marina Ottaway (1977). Land Reform in Ethiopia 1974-1977 (pp. 80--84). African Studies Review, Vol. 20, No. 3, Peasants in Africa, 79-90. doi: 10.2307/523755 [HUB]

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Dessalegn Rahmato (1984). Agrarian Reform in Ethiopia (p. 37). [PDF] Uppsala: Scandinavian Institute of African Studies.

- ↑ PMAC (1975). PROCLAMATION No. 31 OF 1975: "A PROCLAMATION TO PROVIDE FOR THE PUBLIC OWNERSHIP OF RURAL LANDS". [PDF] Negarit Gazeta No. 26.

- ↑ 10.00 10.01 10.02 10.03 10.04 10.05 10.06 10.07 10.08 10.09 10.10 Alula Abate and Tesfaye Teklu (1980). Land Reform and Peasant Associations in Ethiopia- Case Studies of two widely differing Regions (pp. 10-11). [PDF] Northeast African Studies, Vol. 2, No. 2, 1-51.

- ↑ Edited by: Elina Oinas, Henri Onodera and Leena Suurpää (2018). What Politics? Youth and Political Engagement in Africa: 'Students' Participation in and Contribution to Political and Social Change in Ethiopia (Abebaw Yirga Adamu and Randi Rønning Balsvik)'. Youth in a Globalizing World, Vol.6. BRILL. doi: 10.1163/j.ctvbqs5zx.22 [HUB] [LG]

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 12.6 Paulos Milkias (1980). ZEMECHA--AN ASSESSMENT OF THE POLITICAL AND SOCIAL FOUNDATIONS OF MASS EDUCATION IN ETHIOPIA (pp. 20-23). Northeast African Studies, Vol. 2, No. 1.

- ↑ Alula Abate (1983). Peasant Associations and Collective Agriculture in Ethiopia: Promise and Performance (p. 119). [PDF] Erdkunde, Bd. 37, H. 2, 118-127.

- ↑ Berhane S. Tadese (2021-02-06). "The tumultuous years of the 1970s in Contemporary Ethiopian History: A Memoir, 1975: Serving in the National Youth Campaign “Zemecha”" borkena. Retrieved 2023-06-04.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Paulos Milkias (1980). Mass Campaign in Ethiopia — the Political Economy of Education for National Reconstruction (p. 189). The Journal of Educational Thought (JET) / Revue de la Pensée Éducative, Vol. 14, No. 3, 187-195.

- ↑ "ETHIOPIA: Images of the Ethiopian Revolution; Zamacha Campaign, 1974" (2012-01-21). corfu blues and global views. Retrieved 2023-06-04.