More languages

More actions

| Song 宋 | |

|---|---|

The Song dynasty at its peak in 1111 | |

| Dominant mode of production | Feudalism |

| Government | Monarchy |

The Song dynasty was a dynasty of imperial China that existed from 960 to 1279.

History[edit | edit source]

Founding[edit | edit source]

In 960, the Five dynasties period officially came to an end. A pair of brothers, Zhao Guangyin and Zhao Guanyi, seized power in the last of the five dynasties state. They overthrew the young king and proclaimed their own dynasty, the Song—named after their place of origin.[1]

The two brothers succeeded one after the other on the throne for a total of 35 years, but their two reigns are sometimes counted as just one. They were military commanders who had come to the throne by military means, and thus faced a very urgent problem: anybody else with means and resources could challenge their rule and seize power from them in turn.[1]

To avoid this fate, they carried out military campaigns to reunify China. By the end of the decade, they had militarily re-established an empire—though smaller than the Tang empire even at its largest, not venturing as far into the frontiers.[1]

War against the Liao[edit | edit source]

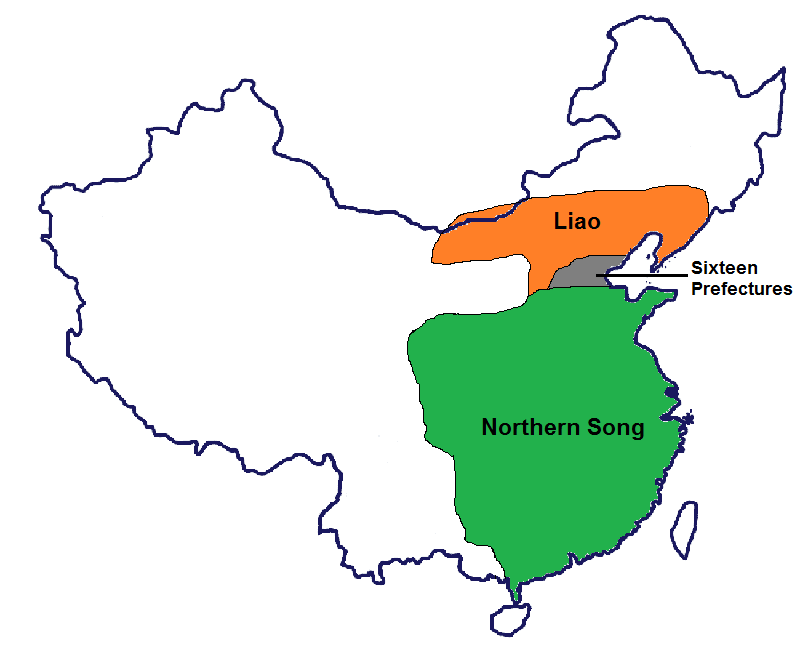

When the Song dynasty arose after 960, they aimed to regain this lost territory controlled by a non-Chinese ruler. In the year 1004 and again in the year 1044, major military campaigns were launched against the Khitan to try and seize the 16 prefectures. Both of these campaigns were however unsuccessful. This resulted in humiliating moments for the Song dynasty, and the Song were forced to sign treaties with the Liao; this was quite a change for the Chinese empire who, as a major power in the region, had previously never signed agreements with another power. What they ended up agreeing to was to pay annual tribute to the emperors of the Liao dynasty, in gold and precious cloth (such as silk). These subsidies were doubled after the second unsuccessful campaign of 1044.[2]

After the second failure, the Song decided that military reconquest was not a cost-effective method of regaining this territory and stopped launching more campaigns. For the Khitan, these tributes are a very significant source of income. For the Chinese, while not being a large economic drain, the tributes were a very humiliating situation however.[2]

As time went by, the Liao dynasty evolved in various ways. The Chinese population inside the Liao state made up 70% of the total population, and as such the Khitan developed a system of dual administration: in the 16 prefectures, which was populated by their Chinese population, they used the Chinese bureaucratic system that was already in place before the Khitan arrived. This was very effective for the purposes the Liao desired, which was to extract wealth from these lands and keeping the people living there away from rebellion. In the rest of the Liao state, they retained traditional Khitan ways—at least most of the time; a process took place over long periods of time by which the Liao court became more like the Chinese bureaucracy they had sought to emulate as the Khitan rulers get used to living a Chinese imperial lifestyle.[2]

This eventually alienated Liao emperors from traditional Khitan customs, resulting in tensions within the Khitan people. The Khitan emperors would also reward their followers by often granting them bits of land from the 16 prefectures. As they granted these lands however, they often became tax-exempt and took away a major source of revenue for the Liao state. The tributes coming in from China were helpful, but not sufficient to offset this loss.[2]

Eventually, late in the 11th century, the Liao state had trouble paying its military forces. Unrest was beginning to spread among the Chinese population, and insurrections began to take place against Khitan rule. In parallel, the Chinese had devised a strategy to retake the 16 prefectures: they found another non-Chinese people, the Jurchen, who could open a front with the Khitan that would divert them from defending the 16 prefectures.[2]

The Jurchen lived further north than the Khitan and some had been incorporated in the Liao state. China used this situation to incite the "free" Jurchen, living outside of Liao territory, to invade the Liao state by sending gifts and advisors. In particular, they encouraged a Jurchen ruler named Aguda to defy the Liao emperor. In the 1120s, the Jurchen launched military campaigns against the Khitan. By this time, the internal problems of the Khitan had developed to the point that they could hardly mount a defense against the Jurchen. To further weaken the Liao state, China also cut their tributes.[3]

In several years, the Jurchen managed to invade and destroy the Liao dynasty. However, while China had expected to have a docile neighbour who had taken care of their problem for them, they actually had a rude awakening: after the Jurchen had been trained, organised and successfully destroyed the Liao state, they continued their campaigns down into China and in the latter part of the 1120s, they had seized much of Northern China—notably capturing the northern Song capital at Kaifeng along with the emperor himself and his mother. They were carried off to the north in captivity and were never ransomed, instead living the rest of their life there while another emperor was put on the throne.[3]

After the capture of Kaifeng, the Chinese court fled south, which instigated a period of several years where the Jurchen armies were effectively chasing the Chinese court from one place to another.[3]

Finally, the Song forces were able to regroup and mobilize forces and push back against the Jurchen, ultimately being unable to drive them all out of China. By the early 1130s, a clear line of demarcation between Chinese and Jurchen-controlled territories had emerged, located about midway between the Yellow river and the Yangtze river.[3]

This marked the beginning of the Southern Song for China, the second half of the Song dynasty. Their new capital was established at the city of Hangzhou, located on the southern coast of China.[3]

Southern Song[edit | edit source]

The reunification of China remained very important in the Southern Song, though no serious efforts were made after a Chinese general was betrayed during the war and lost the empire's last chance to challenge the Jurchen.[4]

The capital at Hangzhou was considered a temporary capital, with the permanent and "real" one being at Kaifeng, showing how much the Chinese intended to reconquer the North. However, the Song dynasty ended up never achieving that goal as a little over a hundred years later, the Mongols conquered China and established their own empire there.[4]

By the geographical nature of the terrain the Southern Song had come to possess (located in Southern China), their economic base had radically altered from the time they had possessed a whole, unified China. As seen previously, the north of China consisted of mostly agricultural (and indeed high-yielding) plains, forming the breadbasket of China in history. By contrast, the southern parts were hilly, with centres of population being separated by difficult to parse hills, river valleys and low mountains.[5]

The population of the Southern Song amounted to 60% of the total population of Chinese people. Beginning in the Tang, there had been a shift in the region populations gravitated towards. Back in the Han and earlier times, the great majority of Chinese people lived in the North or to the West. As China expanded geographically, people migrated to the South which resulted in a greater dispersal of people. By the end of the Tang dynasty, the majority of Chinese had come to live in the South. This trend reversed by the end of the Southern Song and today, there is about an even distribution between North and South China.[5]

Economy[edit | edit source]

Specialization[edit | edit source]

All of these factors led to differences in the economic base of the Southern Song. Notably, there came to be a trend towards local economic specialization—the production of certain commodities became the specialty of certain locations. For example, tea had been grown more or less everywhere alongside grain and other crops. Under the Southern Song, tea came to be mostly grown in Zhiejang and Hunan provinces who abandoned other crops (including grain, which was a staple of subsistence farming) to focus on tea. Grain thus required to be imported, and long-distance systems developed to supply the regions with food.[6]

The city of Jingdezhen became a great center of ceramics. Ceramics had been produced in China for millennia and many centers had developed. Jingdezhen however industrialized production; the imperial kilns were located there, and production was organized on a basis similar to assembly lines. Thousands of workers were employed, with teams running the kilns 24 hours a day. Distribution was also handled industrially: warehouses were built for storage, and then shipped not only all over China, but also made their way regularly as far as the Persian Gulf. From there, they could be shipped all over the world; Jingdezhen wares have been found as far as the Western coast of Africa and Mediterranean countries, making them a truly global commodity—all regulated by the imperial state.[6]

Monetary policy[edit | edit source]

The imperial state, while continuing to be a Confucian government, put in place a number of policies which actively encouraged the growth of the commercial economy (trading)—particularly though monetary policies.[7]

The state encouraged and carried out a great expansion in the money supply which, at the time, was backed by precious metals. These policies had an international dimension as well; Song coins were allowed to leave the country and spread throughout East Asia, becoming the common currency in Japan and Korea at this time.[7]

The Southern Song also experimented with paper money, which was a fairly radical development. The Chinese recognized the use of money as a universal means of circulation or universal commodity, recognizing that it did not have to be a precious metal so long as it was accepted as having value by the people who used it. While not much paper money left the borders, it did circulate quite widely within China. The experiment didn't work out as well as intended however, and paper money fell out of use after the Song dynasty.[8]

Growth of the merchants and artisans[edit | edit source]

These factors fostered the growth of a new class, merchans and artisans which derived their wealth not from agriculture or landlording, but from the production of goods and subsequent distribution and sale.[9]

This started to apply some stress to Chinese society. In classic Confucian thought, merchants were at the bottom of the social strata, considered to be morally tainted (although they were recognized to have some social utility). Up until the Southern Song, the limited presence of merchants did not create a big problem for the state due to how they were perceived. However, as commercial activity expanded wideld, so did not only the numbers of merchants but the wealth they concentrated in their hands as well. Towns grew, where large numbers of merchant families made their home. They built elaborate mansions, wore fine clothes (often the same kind the educated elite would be wearing), had themselves carried around in chairs by servants, and eventually started emulating the culture of the elite: they bought books and paintings, they established libraries, funded public works projects, sponsored monasteries, etc.[9]

This created tensions between the emerging commercial class and the established feudal elite who made their money on agricultural production; a situation highly reminiscent of the rise of the bourgeoisie in Europe and their later struggles against the established feudal order (even happening around the same time in history).[9]

In China, this development took a different trajectory; the contradiction between the two classes was able to be diffused to some extent. This can be explained by the convergence of interests that happened early in the Song dynasty: wealthy landowing families started to take some of the wealth they were earning from their agricultural revenue and invested it in commercial enterprises, making there commercial partners. At the same time, merchants who were becoming wealthy wanted to reinvent themselves as these educated, elite families and bought land to set up their estates. After a generation or two, they would train their sons to take the imperial examinations to cement their shi status.[9]

Government[edit | edit source]

To secure these new land acquisitions, the Zhao brothers established a civilian bureaucratic government which had been the norm since the Han dynasty; the mechanism to fill this government was to turn to the aristocracy and wealthy families who could afford to educate and spare their sons for government service.[10]

Following the civil war and dissolution of the Tang however, almost all of these aristocratic families had simply vanished and died off. Their land titles had been seized and burned during rebellions, and the family members would be executed by peasant rebels when they marched on the estates. Noble families would also serve as generals at war, of which there was plenty during the late Tang, and died there. When administrative centers were fought over and captured, the conqueror would often burn documents.[10]

Examinations[edit | edit source]

Essentially, the Zhao brothers did not have this aristocratic and educated base from which they could recruit. To solve this problem, they looked towards the past and found the imperial examinations that had been started in the early Han dynasty, albeit as a minor mechanism for recruitment. While this system did not become the sole means of recruitment, it was expanded and became a central institution of the Song dynasty. The other two main means of recruitment were by recommandation from someone in the administration, and through the Yin (shadow) privilege. Officials could extend the shadow privilege to their sons who did not have to go through any other qualifying procedures.[10]

Still, the examinations remained the main avenue for recruitment; looking at the highest-ranked members of the Song administration (who made policies) reveals that the great majority of them were people who came in by the imperial examinations.[10]

While legally speaking, almost anyone could take the imperial examination, some groups were excluded by default, the biggest of which being women. Merchants, who were the second most significant group in terms of numbers, were also banned from taking the examination through generations (their sons and other descendants were automatically ineligible). This had to do with the Confucian system which considered merchants to have very low social utility as they didn't produce anything themselves.[11]

While this left around 50% of the population technically eligible for the exams, one needed to be educated in order to even show up at the exam, which were out of reach for many families who could not spare the labour-power and finances required to educate their son.[11]

The examination process itself took inspiration from the Confucian revival seen under Han Yu. The exams tested the candidate's mastery of a body of Confucian writing, historical texts and classical literature. The candidate needed to be able to cite texts from memory and apply them to questions of government or administration. They also needed to be able to compose poetry, writing in an elegant literary style.[11]

This central place the imperial examinations took in the material base of the country influenced its superstructure heavily, and it became an institution of Chinese culture that survived for the next thousand years: preparing for the exams, taking the exams, being part of this system is what gave a sense of self and community to the elite. Whereas the old aristocratic families received their identity from being great families listed in the registry, the new elite families from the Song dynasty onwards however, people attained this prestige and status by participating in the imperial examination system, making them the educated shi of older times. This is also around the time the term shi came to mean not solely an advisor, but an educated person or a scholar as well.[12]

Members of this strata knew each other from their participation in a shared literate culture, extending to people even who did not pass the exams; these were very tough to pass, held at two levels: local and national (and later provincial level). The pass rate at each level was only about 10%, with a fewer proportion of people attending exams at each higher level. On average, 100 people passed the exam every year. Those who failed their exam were still educated however, and came to constitute the scholar class.[12]

Culture[edit | edit source]

The importance of the imperial examination system as an institution of imperial China from the Song dynasty forward led to a major cultural crisis in the Chinese educated elite, who went through a process of self-realized and realized what exactly their role was and what they should do with the power they possessed, being not only educated and literate but also in the government administration.[13]

The shi in the Song dynasty came to the conclusion that by having passed the imperial examinations (or even having attended them) and being educated individuals, they had access and were part of a system of governance and social leadership which they took as a very deep responsibility. Their official positions also afforded them some privileges; for example, they were exempt from labour duties in which a subject had to render to his liege at some time during the year. They were also exempt from corporal punishment.[13]

Even those who only attended the examinations but didn't pass could find a role in public and social life, serving as teachers for example, and Dr. Hammond notes that many private academies flourished during this period. They could also become tutors or clerks and secretaries in government. Still, this social class remained a very small portion of Chinese society, amounting to 5-6% of the total population at most.[13]

Philosophy[edit | edit source]

Two similar groups of scholars came to emerge during this period:

The first group were the Wen ren. Wen translates in this context as "literary culture"; it has to do with things that are written or produced with writing tools (such as painting or calligraphy). Language, poetry, prose writing, the classics, etc. fall under the general rubric of Wen. Ren means person or people, so Wen Ren in English translates as "literary gentleman".[14]

The second group was also very concerned with literary culture but approached it in a somewhat different way. They were called the Jing shi, meaning "ordering the world" or "statecraft"; they were focused on the application of the literary body towards the management of state affairs and government.[14]

Both shared a faith in the literary textual tradition as a repository of knowledge and values, which were very important to these Confucian scholars.[14]

Important individuals in the Wen ren group were Ouyang Xiu and Su Shi. While Ouyang was a generation older than Su, they both knew each other and were good acquaintances. They came to know each other when Ouyang was the chief examiner in the year 1059, the same year Su passed his examination at the top of his promotion. Ouyang used his role as an examiner to promote his particular views, drawing upon Han Yu from the Tang dynasty; he was a practitioner of the Gu Wen principles, and gave preference to prospective examinees who wrote in the Gu Wen tradition of a clear, concise, to-the-point style. Su Shi was one of those and ranked in large part because of the style of his writing. From there, they looked at the literary heritage as a source of inspiration, knowledge and information, but also as a reservoir of good examples to follow in terms of values and qualities to live by.[15]

There were still differences between the two acquaintances; Ouyang Xiu was an antiquarian, very interested in the past, collecting antiquities. He saw the literary past as a repository to inspire him. Su Shi, while having the same kind of immersion and familiarity with the past, aimed to achieve such a complete assimilation of that material that he could then spontaneously good writing. But in order to achieve that spontaneity, it was necessary for him to immerse oneself into the models of the past so as to absorb the values and manifest these good qualities.[15]

The Jing Shi thinkers shared concerns for the records of the past with the Wen ren, but had a more practical bent to this body of texts. They were concerned with how one could draw from the literature of the past, its examples and values, to solve the problems of society in their day.[16]

Sima Guang and Wang Anshi knew each other (as well as Ouyang Xiu and Su Shi); hey all lived in the same cities, went to the same social events, knew each other at court and were part of a shared cultural milieu.[16]

In the late 1060s, Wang Anshi rose to the top of the imperial administration, being named chief minister of the imperial government. He was then given the authority by the emperor to launch a major reform program which he undertook based upon his personal interpretation of the history of the past. These were called the new policies, setting out to foster a more proactive state that will intervene in society to benefit the people. These policies involved, for example, the creation of state-sponsored schools to make education more widespread and a system of regulated agricultural loans so farmers would not be dependent on loans from aristocratic (landlord) families.[16]

Sima Guang is considered to be the other greatest statecraft thinker of this period, but he was rabidly hostile to the ideas of Wang Anshi, showing that while they drew from the literary body of Chinese history to inform their views, they did not come to the same conclusions at all. When Wang Anshi was named as chief minister, Sima Guang resigned government and retired from the capital at Kaifeng, moving west to the ancient capital of Luoyang. In the 1070s, after Wang Anshi was dismissed from his positions, Sima Guang was brought back and set out to dismantle the policies of Wang Anshi.[16]

His opposition to Wang Anshi's ideas was based upon a different interpretation of the values to be derived from the literary record of China: while Wang Anshi called for intervention to bring about a Confucian order, Sima Guang argued that the state should keep its hands out of society, and that the emperor should rely upon those within society with a "natural role" as leaders to address the problems their communities face. One way to interpret Sima Guang's views is to see him as defending the leading role and autonomy of the shi; the shi being extracted from the wealthy land-owning class, i.e. those with privilege.[16]

Cosmology[edit | edit source]

At the same time, a third position grew in the shi; a group concerned with linking human affairs to larger cosmic orders and natural systems. In the Northern Song, some thinkers began to place emphasis on a concept very different from Wen, which they called Li. While Wen refers to things literary or the "pattern" formed by words on a page, which by definition are man-made. Li on the other hand refers to patterns that occur in nature, the word coming from the striped patterns that appear on some types of rocks. The word Li itself means pattern or principle.[17]

This distinction was fundamental to the cosmological thinkers, who were concerned with trying to understand the naturally-occurring patterns of the world around them. They saw moral values as coming not out of Wen but being derived directly from natural patterns, because they were embued with normative values. That is to say, patterns that can be observed in nature do not inform simply the way things are, but the way things should be—giving them a moral value. In some ways, this calls back to the Confucian ideal of the Dao ("way"), being the proper order of things which is inherently desirable.[17]

In the Li cosmology, acting in accordance to those patterns makes one's actions morally good, while acting against the patterns or principles make one's actions bad. Initially, the cosmological thinkers didn't reject Wen but argued that it was a mediated experience; relying on the writings of the past was to rely on a humanly constructed understanding of the world. While there were insights to be gained there, they argued, it was not the same as directly apprehending the patterns and principles of the universe.[17]

Neo-Confucianism[edit | edit source]

As the material base in the (Southern) Song changed, so did the character of its ideas. It is during the Song dynasty that Neo-Confucianism (dào xué, 道学, "the learning of the Way") emerged, theorized by Zhu Xi (1130-1200). He took after the cosmological thinkers of the past, notably those from the earlier Song dynasty, bringing all of their theories and methodologies in a coherent body of philosophy.[18]

It should be noted that neo-Confucianism is a misnomer of sorts. While this is how dào xué is customarily called in the West and in English, it is not the name used in China. The distinction is significant because in traditional Chinese culture, one does not want to invent something "new" or "neo", but rather one wants to return to the correct interpretation of the past. Dào xué, while being "new" in the sense that it was developed as a coherent body of philosophy in the Southern Song dynasty millenia after Confucius, was not emphasized by Zhu Xi as being new, but as returning to the correct interpretation of the classics.[18]

The core of Zhu Xi's argument is that there had been a shift in the source of moral values, from the primacy of the literay cultural tradition (the Wen) to a primacy of the direct understanding or apprehension of the natural patterns and principles of the universe (the Li). He believed that by observing natural patterns and deriving principles from them, one could ground morality in a very firm basis—not being solely a matter of convention or what people had decided amongst themselves, but a natural order more powerful than humans.[18]

Further, he argued that this was exactly what the sage emperors of Antiquity did—emperors like Yao and Shun, who had harmonized themselves with the patterns and principles they'd seen around them, and thus why they were sages.[18]

Therefore, to Zhu Xi, the Wen was useful as a record of how people had understood those insights of the ancients; Wen shouldn't be taken as a source of values in and of itself, but as a way of approaching an understanding of the ancient sages believed and carried out. Deriving a sense of values would happen, for Zhu Xi, through both studying the ancient texts from this point of view and from studying phenomena in the world.[18]

The critical figure in this process was the "gentleman" (Junza) that Confucius upheld as a model of good values for everyone to follow. In practice, this meant the shi, the educated elite. The junza would essentially be the invidual who puts the quest for moral values into practice; he sought to develop and cultivate his own moral qualities, while being engaged in the process of making the world a better place. In that process, he would have to undertake studies, but also what Zhu Xi called the "investigation of things" (gé wù, 格物). These practices would prepare the junza to be a good person, lead a good family life, and thus be able to carry on the affairs of the state.[18]

Zhu Xi did not reject the textual tradition, but he did take a very critical approach to it, unlike the Northern Song elite. He did not care much to immerse himself in the textual tradition and absorb values from it, but he did say there were elements of value in this tradition. He was uncomfortable with the "commentarial" tradition; the body of texts which sought to interpret the teachings and writings of the Ancient over the past millenia and a half. Zhu Xi thought that these later texts obscured the meanings of what the original authors had actually said (or actually intended to say). He thus advocated a return to the classics, engaging directly with them.[18]

One of Zhu Xi's legacies was the selection of four texts he considered to be fundamental to his philosophy, making them the centerpieces of his educational program. The Confucian classics in Chinese history varied throughout the eras, with there at times being 5, 8, or even 13. Two of Zhu Xi's four texts were the Analects of Confucius (written by his students after his death) and the book of Mencius (Confucius' most famous follower, written a century and a half later). These two texts had always been in the classical canon, and were full-length books. The other two texts he considered fundamental were chapters taken from a longer work called the Liji, which is a record of ritual activities of the early Zhou dynasty. These two chapters of the Liji are called the doctrine of the Mean and the Great Learning.[18]

This chapter of the Liji perhaps encapsulates Zhu Xi's philosophy best. The Great Learning is not a long text, but it follows a very careful course of development, starting by referring back to the ancients (who wished to bring order to the world). There is a short preface before that to explain what the great learning (the Dao) is: manifesting one's virtue in the world, or in practical terms, "knowing when to stop" (as quoted from the book).[19]

The ancients who wished to bring order to the world, according to the Great Learning, firstly had to govern well. To achieve that, they followed a logical sequence, which can be explained in this manner: they first had to get their family to be well-ordered, properly organized and run. But to achieve that, they first had to rectify and cultivate themselves. To achieve that, they tried to get their consciousness clear, which they realized required them to extend their knowledge. Finally, to extend their knowledge, they started by engaging in the investigation of things (gé wù).[19]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Dr. Ken Hammond (2004). From Yao to Mao: 5000 years of Chinese history: 'Lecture 14: Five Dynasties and the Song Founding'. The Teaching Company.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Dr. Ken Hammond (2004). From Yao to Mao: 5000 years of Chinese history: 'Lecture 17: Conquest States in the North'. The Teaching Company.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Dr. Ken Hammond (2004). From Yao to Mao: 5000 years of Chinese history: 'Lecture 17: Conquest States in the North'. The Teaching Company.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Dr. Ken Hammond (2004). From Yao to Mao: 5000 years of Chinese history: 'Lecture 17: Conquest States in the North'. The Teaching Company.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Dr. Ken Hammond (2004). From Yao to Mao: 5000 years of Chinese history: 'Lecture 18: Economy and Society in Southern Song'. The Teaching Company.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Dr. Ken Hammond (2004). From Yao to Mao: 5000 years of Chinese history: 'Lecture 18: Economy and Society in Southern Song'. The Teaching Company.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Dr. Ken Hammond (2004). From Yao to Mao: 5000 years of Chinese history: 'Lecture 18: Economy and Society in Southern Song'. The Teaching Company.

- ↑ Dr. Ken Hammond (2004). From Yao to Mao: 5000 years of Chinese history: 'Lecture 18: Economy and Society in Southern Song'. The Teaching Company.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Dr. Ken Hammond (2004). From Yao to Mao: 5000 years of Chinese history: 'Lecture 18: Economy and Society in Southern Song'. The Teaching Company.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Dr. Ken Hammond (2004). From Yao to Mao: 5000 years of Chinese history: 'Lecture 14: Five Dynasties and the Song Founding'. The Teaching Company.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Dr. Ken Hammond (2004). From Yao to Mao: 5000 years of Chinese history: 'Lecture 14: Five Dynasties and the Song Founding'. The Teaching Company.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Dr. Ken Hammond (2004). From Yao to Mao: 5000 years of Chinese history: 'Lecture 14: Five Dynasties and the Song Founding'. The Teaching Company.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Dr. Ken Hammond (2004). From Yao to Mao: 5000 years of Chinese history: 'Lecture 15: Intellectual Ferment in the 11th Century'. The Teaching Company.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Dr. Ken Hammond (2004). From Yao to Mao: 5000 years of Chinese history: 'Lecture 15: Intellectual Ferment in the 11th Century'. The Teaching Company.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Dr. Ken Hammond (2004). From Yao to Mao: 5000 years of Chinese history: 'Lecture 15: Intellectual Ferment in the 11th Century'. The Teaching Company.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 Dr. Ken Hammond (2004). From Yao to Mao: 5000 years of Chinese history: 'Lecture 15: Intellectual Ferment in the 11th Century'. The Teaching Company.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 Dr. Ken Hammond (2004). From Yao to Mao: 5000 years of Chinese history: 'Lecture 15: Intellectual Ferment in the 11th Century'. The Teaching Company.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 18.4 18.5 18.6 18.7 Dr. Ken Hammond (2004). From Yao to Mao: 5000 years of Chinese history: 'Lecture 19: Zhu Xi and Neo-Confucianism'. The Teaching Company.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Dr. Ken Hammond (2004). From Yao to Mao: 5000 years of Chinese history: 'Lecture 19: Zhu Xi and Neo-Confucianism'. The Teaching Company.