Battleground Tibet: History, Background, and Perspectives of an International Conflict (Albert Ettinger)

More languages

More actions

Battleground Tibet: History, Background, and Perspectives of an International Conflict | |

|---|---|

| |

| Author | Albert Ettinger |

| Written in | 2015 |

| Publisher | 五洲传播出版社 (China Intercontinental Press) |

| First published | 2015 Frankfurt-am-Main Originally published in German by Zambon Verlag |

| Type | book |

| ISBN | 978-7-5085-3398-8 |

| https://annas-archive.org/md5/53deec57ed312cebc0244f314661d777 | |

Table of Contents

Preface

1 Lots of questions, and no hasty answers please!

2 Historiography and journalism between facts, myths and propaganda lies

3 More than one thousand years ago: Chinese culture for a kingdom of barbaric warriors

4 Common history: the Mongolian, Ming, and Manchu emperors

5 "Chinese cake" on the menu for greedy colonial powers

6 Tibetan "independence" as a project of the British Empire

7 The 13th Dalai Lama, tyrant of Lhasa

8 Failed modernisation, failed "state": Tibet under the 13th Dalai Lama and his successors

9 Three rusting cars, bagpipes and play money printed by hand

10 After the thirteenth: intrigues, banishments and squeezed-out eyeballs

11 Lamaist greed and immorality: His Holiness Reting Rinpoche

12 Civil war in Lhasa: political murders, belligerent monks, and a ransacked monastery

13 Reting's most important legacy: a "Chinese" Dalai Lama

14 The "Tibetan trade mission": Great Britain and the USA refuse to grant the "lama state" international recognition

15 A new type of army, Red Scare and 17 points as the basis for peaceful liberation

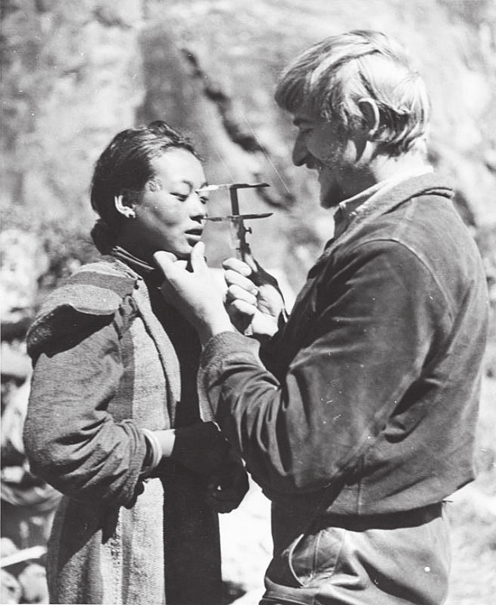

16 "Winds of Change" – approaches to reform, a political honeymoon, and a forgotten love poem

17 Hunger, economic boycott, and a Tibetan Ku Klux Clan – reactionary circles thwart the 17 Point Agreement

18 The early exile, the "holy family" and the rich uncle from America

19 Khampa uprising: robbers and "holy warriors" become CIA "freedom fighters"

20 Lhasa 1959: Khampas and the CIA stage a "people's uprising" and bring the Dalai Lama out of the country

21 "Tibet" in exile: mismanagement, prosperity at the expense of others and democracy as a facade

22 "International Commission of Jurists": CIA jurists enter the Cold War

23 Stories from wonderland: how a "genocide" resulted in unprecedented population growth...

24 ...and how a "cultural genocide" triggered a cultural blossoming

25 "Give the Emperor what belongs to the Emperor!" – Religious freedom and its limits

26 The human rights to education and development

27 "Tibetans aren't Chinese": the racial argument

28 The Dalai Lama's "Greater Tibet" – a call for racial hatred, ethnic cleansing, war, and genocide

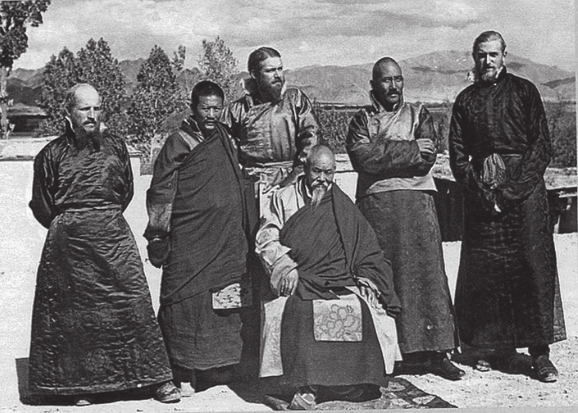

29 Nazi friends of the Dalai Lama: the "Austrian mountaineer" Heinrich Harrer

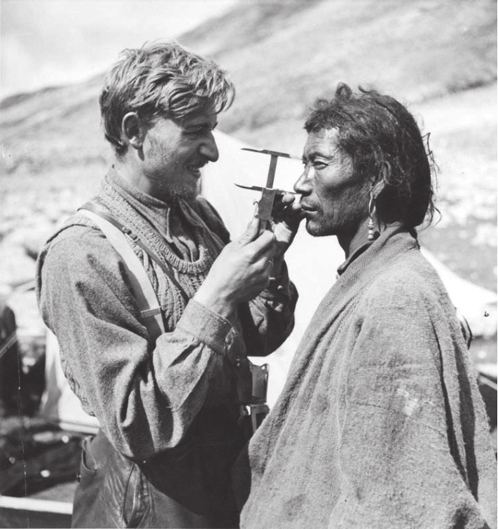

30 Nazi friends of the Dalai Lama: the "race researcher" and war criminal Bruno Beger

31 Nazi friends of the Dalai Lama: the right-wing scene

32 ICT, NED, RwB: continuation of the CIA war with other means

33 Burning for the Dalai Lama?

References

About the author: ALBERT ETTINGER

... was born in 1952 in Differdange, a small industrial town of the Luxembourg steel area, as the first son of a miner. Initially, he studied History, then pursued German and Romance Languages Studies in Trier (Germany), which he completed by a Ph. D. with the rating summa cum laude.

For more than thirty years, he worked as a high school and college teacher in Luxembourg and Trier.

He is married and father of two children.

In recent years, Albert Ettinger wrote two books and many articles about Tibet.

While they marched through the Tibetan regions and towns, no shots were fired at them and they were often welcomed warmly. The foreigners lamenting the fate of a nation that had fallen victim to shameful aggression had been extremely ill informed.

Although we have cloaked our activity on the border of India in the deepest secrecy, who in India and who in Russia would believe that such activity was being supported and directed by anyone else than the covert peacetime operational forces of the United States? ... If the Dalai Lama is spirited out of Tibet in the face of an overwhelming Chinese army of conquerors, are the Chinese going to think he found his support in heaven?

It must also be emphasised that, in Tibet, there is a more active artistic and intellectual life and creativity (literature, music, painting, sculpture and recently film production) than in exile.

Let's achieve autonomy first. And then we'll throw out the Chinese!

Preface

After several years of intensively examining Tibet and the Tibet issue, it was important to me to make my findings and conclusions available to a wider public. Zambon Verlag kindly offered me the opportunity to do this in the form of two books. This book is one of those, and I hope it can go some way towards overcoming the widespread ignorance about the background and causes of the Tibet conflict. This ignorance forms the soil on which prejudices, clichés and propaganda lies can proliferate and take root.

The main concern of this book is to provide information about indisputable yet little or unknown facts and, in doing so, stimulate the reader to look more closely and reflect on the issues – and not just on a superficial level. However, I do not deny that it was occasionally written cum ira et studio and that I do observe, judge and evaluate my subject from a personal viewpoint. The readers must decide for themselves how far they wish to share this viewpoint. In any case, I agree with Karlheinz Deschner who, in a response to critics of his "Christianity's Criminal History," counters the allegation of "one-sidedness" by writing: "Everyone is one-sided! Every historian has their own biographical and psychological determinants, their preconceived opinions. Everyone is established in society, contingent upon his or her class and social group. Everyone is subject to preferences, aversions, knows their favourite hypotheses, their values systems." This particularly applies to those who "most strongly deny it." It is therefore important not to simulate "false objectivity;" what is more critical "is how many reasons underpin our 'one-sidedness' and how good these reasons are," the nature of the "sources" and which "level of reasoning" we are pursuing.1 I think that this book can meet the challenges in this area.

Despite the overriding efforts to communicate facts and information, it also therefore has features of a polemic. The book owes its creation to a situation I experienced a few years ago. While teaching German at a high school, I noticed that our school textbook had treated the issue of "Tibet and Tibetan exile" in a completely one-sided and manipulative manner.2 I was then shocked by events from 2008 when the calls to boycott the Olympic Games in Beijing caused great waves and "activists" for a "free Tibet" physically attacked the people carrying the Olympic flame in France, the USA and other countries. Alongside the standard allegation that China is not a democracy and breaches human rights, the "occupation of Tibet" (almost sixty years ago) provided the foundation for an unprecedented media campaign. Tibet and the Dalai Lama were more than ever the focus of media interest. And the exiled leader of the Tibetan Gelugpa sect or his advocates were given every opportunity to present the viewpoints and assertions of his "exiled government" and its international supporters, particularly as, at the same time (and in no way coincidentally), violent riots in Lhasa were generating headlines. In the media, the central values that Olympic sport should represent and convey were left by the wayside: the requirement for fairness and the goal of international understanding.

Here I would only like to say so much on the issue of fairness: as far as I know, there had previously only been one partial boycott of the Olympic Games or any other large international sporting event, namely in 1980 when the USA and other western countries refused to take part in the Olympic Games held in Moscow. The reason or pretext for this refusal at the time was the military intervention of the Soviet Union in Afghanistan. However, neither the recent western military action there and the associated civilian victims, nor the earlier wars and interventions by the USA in Indochina, Latin America, or Iraq3 resulted in our media or leading circles demanding a boycott of any international sporting event in the USA. Breaches of international law and human rights by Israel were equally never a sufficient reason to introduce any form of boycott measure. Yet there was no question that there had been significant and repeated breaches of international law and human rights by the USA and Israel.4 This does not apply to the Chinese Tibet policy, as we shall show.

As this book does not otherwise rest on personal experiences, I naturally had to rely on credible sources, relevant historical research, and written reports from contemporary witnesses. Yet, which sources and authors can be considered credible and, above all, for whom? I personally, for example, tend to consider critics of the Dalai Lama to be credible; yet many readers will probably trust the former god-king and his companions. This particular dilemma can be solved, as I also consider the latter credible, at least occasionally. When they report on events or make admissions diverging from the position they generally tend to adopt, they are actually very credible.

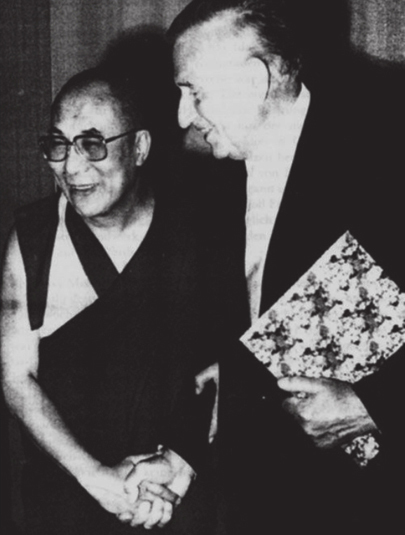

This explains why I rarely call upon opponents of the Dalai Lama5 and his "exile government". The Tibet lobby counters any justified criticism with the cheap killer argument that somebody has embraced the propaganda of the Chinese Communists.6 I therefore primarily rely on authors and sources who are above such suspicion: American military historians and CIA insiders or written documents from Tibetan "Buddha warriors," renowned western academics such as Melvyn Goldstein, Tom Grunfeld, Barry Sautman, Andreas Gruschke or Thomas Hoppe, stated Dalai Lama supporters such as Laurent Deshayes, professed Buddhists and leading "Free Tibet" activists. Contemporary witnesses such as Alexandra David-Néel,7 the French Asia researcher honoured by the 14th Dalai Lama as a friend of Tibet, and Heinrich Harrer, "teacher" and lifelong friend of the earlier god-king and occasionally the 14th Dalai Lama himself, have also been important sources. It should therefore be difficult for the opposing side to react to the information and arguments provided other than with attempted silence or hysterical screams.

One further comment at the outset: as the reader will easily recognise, the uncommented citations at the start of the chapters do not necessarily reflect my own opinion. Instead, they highlight or supplement my own explanations from different, often opposing, perspectives. Occasionally, they are even not directly related to the actual issue, but rather direct attention to more general questions and connections. The thinking reader that I expect will undoubtedly know what to make of them.

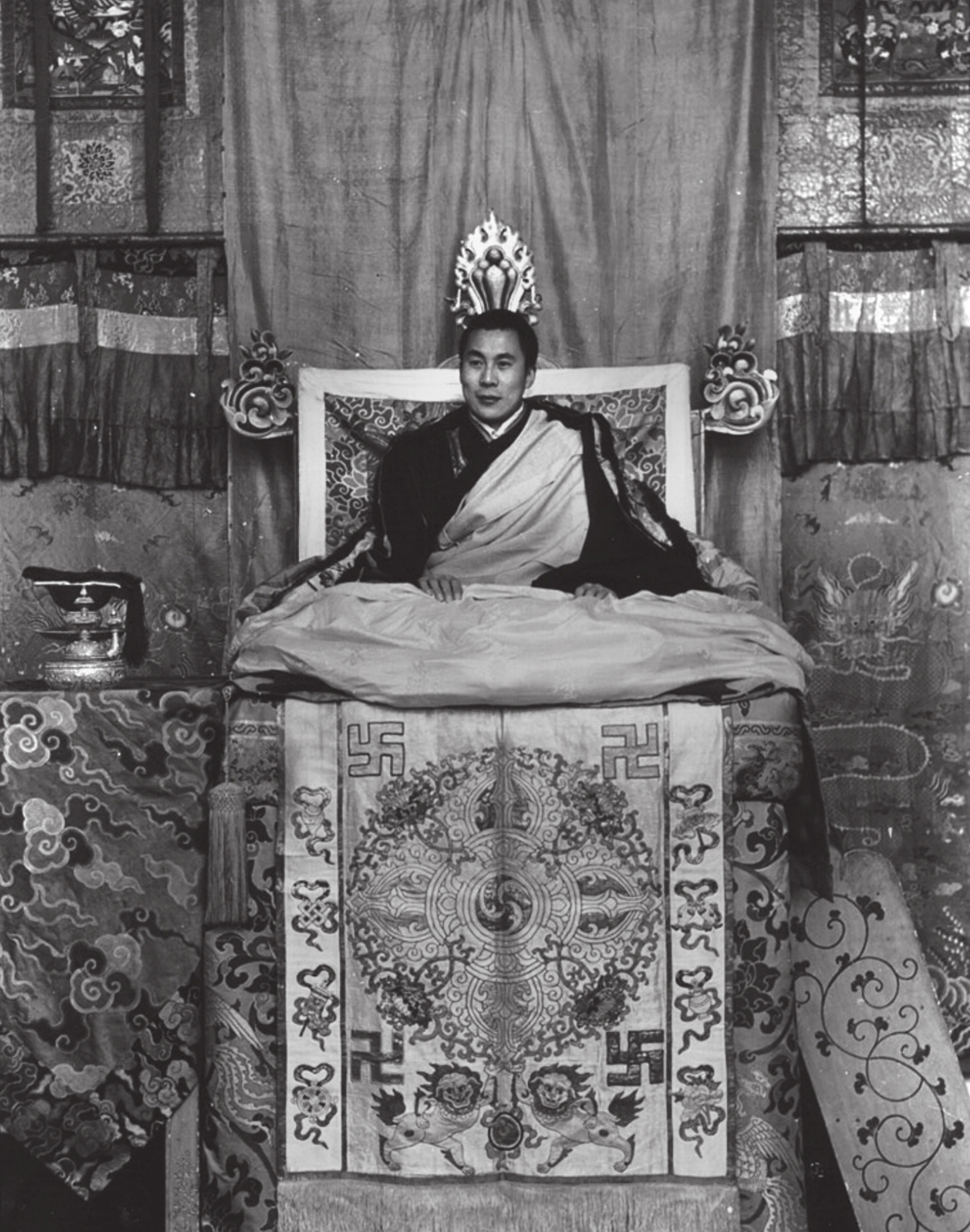

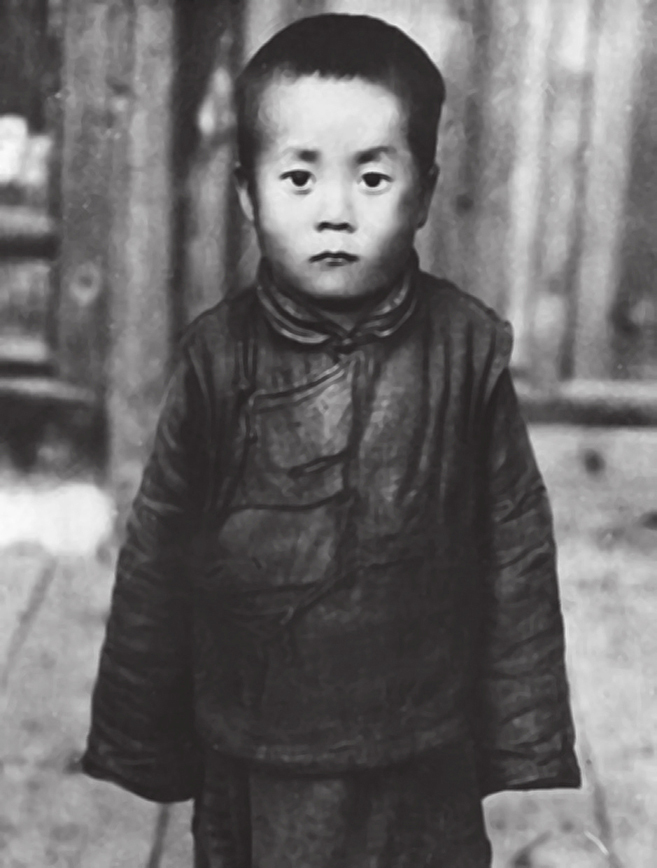

The 14th Dalai Lama on his throne in Lhasa in 1956 or 1957 (photo: unknown source)

Notes

1 Karlheinz Deschner, Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums, Erster Band: Die Frühzeit, Reinbek bei Hamburg, Rowohlt Verlag, 1986, p. 39 2 The reading book deutsch.punkt 3 for twelve or thirteen years old from the Klett Schulbuchverlag openly promotes or promoted Tibetan Buddhism. The headings speak for themselves: "Tibet and the resistance of spirit" or "His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama" (p. 189). As if the authors wanted to convert the pupils to Lamaism, it states: "The path of Buddha is suitable for everyone, not only monks and nuns." Allegedly, the pupils should learn in the relevant sequence about handling factual texts and extracting information from the texts presented. That was done using extracts from a novel for young adults glorifying Lamaism. The only factual text cited cannot be found in the quoted source, a work from Uli Franz intended as a travel guide. It was clearly pieced together for scholastic indoctrination. 3 "Whereas China's apparent human rights breaches in relation to Tibet are highlighted," the summary of the global war on terrorism is "barely acknowledged" in western media, writes Michel Chossudovsky, Professor for Economic Sciences at Ottawa University, Canada, and Head of the Centre for Research on Globalization (CRG): "More than 1.2 million Iraqi civilians have been killed and 3 million wounded. The UN High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) estimates the number of Iraqi refugees who have left their country at 2.2 million and the number of those 'driven out internally' at 2.4 million. 'The population of Iraq at the time of the American invasion in March 2003 was approximately 27 million and is now around 23 million. It can therefore be assumed that currently more than half of the Iraqi population are either refugees, require medical assistance, injured or dead.'" (http://www.hintergrund.de/20080627214/politik/welt/operation-tibet-html, accessed on 12/02/2013). Quote: Dahr Jamail, Global Research, December 2007 4 See also the drone attacks with civilian "collateral damage" and the targeted killing, even of US citizens, under Obama. See also Vincent Bugliosi, The Prosecution of George W. Bush for Murder; Vanguard Press, 2008; William Blum, Killing Hope, Zed Books, 2014; Oliver Stone/Peter Kuznick, The Untold History of the United States, New York, London, Toronto, Sydney, New Delhi, Gallery Books, 2012, or Noam Chomsky, What Uncle Sam Really Wants, Tucson/Arizona, Odonian Press, 2005 5 These include Colin Goldner. See also Goldner, Dalai Lama: Fall eines Gottkönigs, Aschaffenburg, Alibri Verlag, 2008 6 As if we in the West would be particularly influenced by Chinese propaganda. How would that work? Rather, we are exposed to the propaganda of western governments, interest groups and their media... 7 The Dalai Lama visited her house in Digne in the Alps of Haute Provence twice, in October 1982 and in May 1986. (See also Maxime Vivas, Pas si ZEN: La face cachée du Dalai Lama, Paris, Max Milo Éditions, 2011, p. 34). He was acknowledging a woman who made a significant contribution to the creation of the western myth of Tibet.

Tibet became to me, at that time, a land of certainties: an independent country had been invaded by Chinese Communists, who destroyed six thousand monasteries and killed 1.2 million people, an exact figure, one-fifth of the population.

On the one hand, the violent annexation of Tibet by China, which was contrary to international law, is internationally known and undisputed; on the other hand, the 14th Dalai Lama has a very good international reputation, not least after being awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1989. As the Dalai Lama advocates non-violence and democratic reforms, China has no argument for the occupation (Tibet is neither a threat, nor must it be protected against "feudal oppressors").

Many writings stress the predatory nature of the Chinese annexation of Tibet, sometimes arguing that the Chinese actions were motivated by a desire to acquire Tibet's natural resources and by a policy of lebensraum. I think this is a misinterpretation of the Sino-Tibetan conflict.

We can make it easy for ourselves when we write about Tibet, the Tibetan conflict, and the Chinese Tibet policy. Just as Franz Alt did. In a quickly pieced together but magnificently designed book4 from 1998, he initially gives the Dalai Lama a chance to speak and then, in his own contribution covering forty pages – including nine photos – addresses the past, present and future of Tibet and the Chinese mainland. For "two thousand years of Tibetan history", his colleague, Klemens Ludwig, needed even less space within the same anthology: twenty-five pages, which are also broken up with photos.

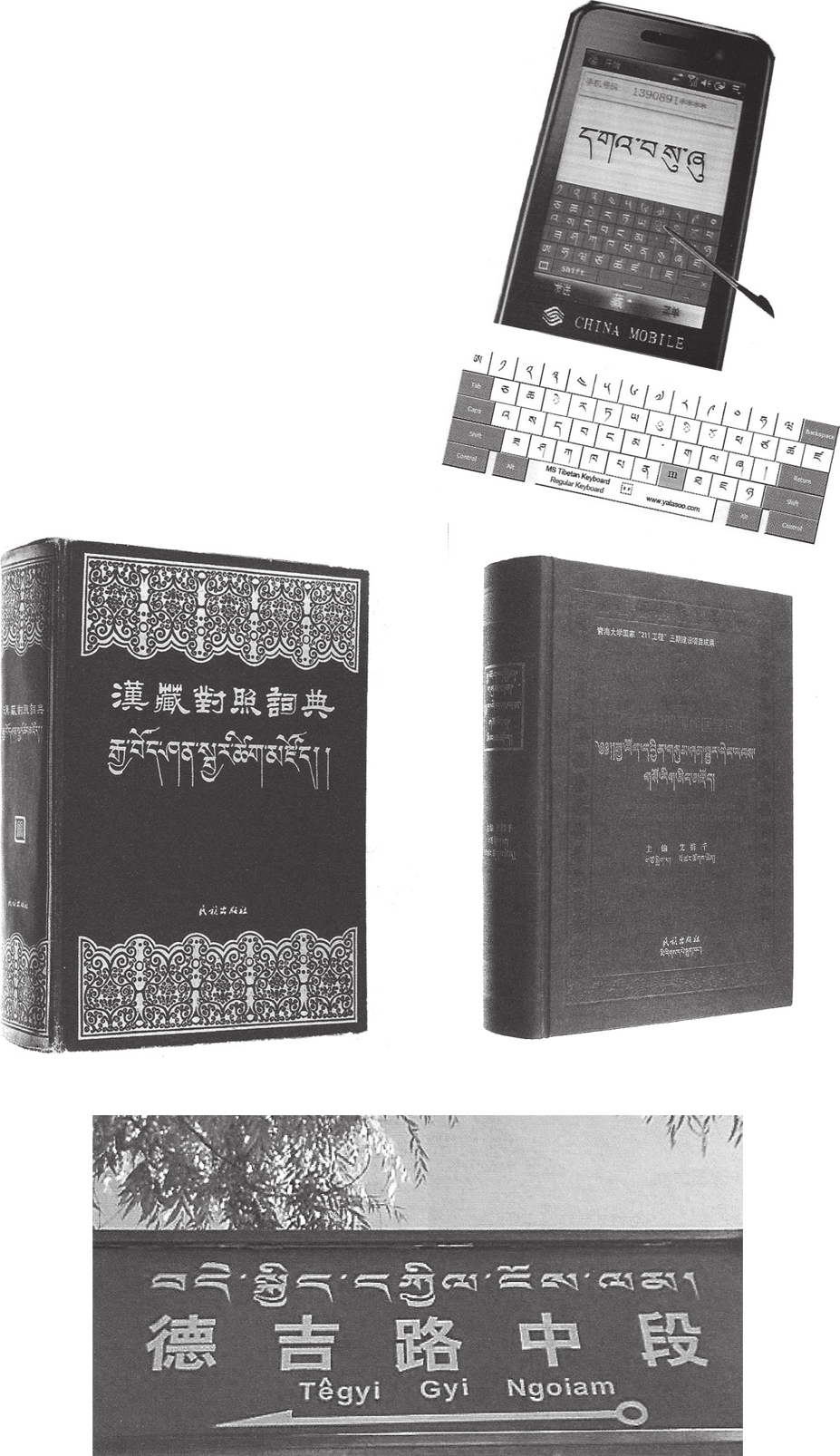

We want to address the issue with somewhat more care and seriousness here by touching on a whole range of political and historical questions and, above all, delving deeper into them. We initially trace the centuries' old cultural, religious, and political relationships between the Tibetans and the mainland, and try to explain, on the one hand, the basis for China's demands on the region and, on the other hand, the independence claimed from exile. In doing so, we must clarify the term "Tibet" that is, for transparent political reasons, consistently used in an unclear manner. We shall address in detail the political impact and character of the 13th Dalai Lama and the regents that followed him. We shall examine whether the Chinese assertion that, in 1951, China finally freed Tibet from foreign "imperialistic" influence has any form of justification, or whether this was a pure fabrication, as is often claimed in the West. We shall try to elucidate whether, at any point in its modern history, Tibet can be considered an independent state. We shall address the conditions of the return of Tibet to the rule of the central Chinese government, referred to by China as a "peaceful liberation," and the so critical first decade within the young People's Republic of China. Incidentally, we shall present the non-academic public with the results of the historical research performed by Melvyn Goldstein for the first time. His monumental history of Tibet from 1913 to 19575 is now justifiably perceived internationally to be the standard work on this issue. We shall then discuss in detail the armed uprising of the late 1950s and 1960s and its protagonists and supporters. We shall investigate whether Tibet now enjoys real or only apparent autonomy within China. We shall pursue questions such as: is there any truth in the allegation of "foreign infiltration" through the Han Chinese? Does the often invoked "cultural" or even physical "genocide," of which China is accused by the "Tibetan exile government" and so-called NGOs, actually exist? Are the "Chinese" really doing everything to destroy the Tibetan language and culture as we are always reading?

We also want to address the methods, goals, and possible perspectives of the "exile government" and their supporters. As the leader of the exile government, does the 14th Dalai Lama really represent a politics of peace, reason, balance, moderation, and non-violence?

You can see that the list of questions is varied and very long. However, it is not complete and we cannot address all aspects of the "Tibet" issue in this book. For example, the question of ownership, power and living conditions in old Tibet – whether it really was a feudal society, paralysed for centuries through extreme social inequality, serfdom, slavery, beggars' misery and brigandage, and a strict clerical dictatorship – is excluded. The same applies to the equally important and necessary discussion of the teaching and practices of Tibetan Buddhism (Lamaism). As these aspects demand and deserve their own detailed treatment, we have addressed them in a separate book. I warmly recommend it to interested readers as a supplement and complement to this one.

Thangka image of the mythical King Gesar of Ling

Notes

1 Patrick French, Tibet Tibet: A Personal History of a Lost Land, New York, Vintage Books, 2003, p. 22 2 deutsch.punkt 3, Sprach-, Lese und Selbstlernbuch für Gymnasien, Lehrerband, Stuttgart and Leipzig, Ernst Klett Schulbuchverlag, 2006, p. 90 3 Tsering Shakya, The Dragon in the Land of Snows: A History of Modern Tibet since 1947, London 1999, p. 92 4 See also Franz Alt/Klemens Ludwig/Helfried Weyer, Tibet. Schönheit – Zerstörung – Zukunft, Frankfurt am Main, Umschau Buchverlag, 1998 5 See also Melvyn C. Goldstein, A History of Modern Tibet, Volume 1: The Demise of the Lamaist State, 1913-1951, Berkeley-Los Angeles-London, University of California Press, 1989; Volume 2: The Calm before the Storm, 1951-1955, Berkeley-Los Angeles-London, University of California Press, 2007; Volume 3: The Storm Clouds Descend, 1955-1957, Berkeley-Los Angeles-London, University of California Press, 2014

2 Historiography and journalism between facts, myths and propaganda lies

Furthermore, we must consider that the spiritual domain differs significantly from the scientific domain, and that scientific evidence is no more truthful than mythologies.

Prof. A. Tom Grunfeld, the Tibet historian from State University in New York notes that, in the case of Tibet, academic historiography that endeavours to remain objective encounters some problems. Firstly, before the seventh century A.D. there was no consistent and structured writing in the Tibetan language area (at a time when the Chinese kingdom was already at least 2,300 years old). The first Tibetan chronicles were written in the eighth and ninth century, when it seemed important to the ruling powers at the time to see their legitimacy as the descendants of an entire succession of rulers confirmed.2 The rise of Buddhism to a main religion also brought about a rewriting and reinterpretation of history.

The early history of the region ("Tibet" did not yet exist, just as in antiquity there was no Germany, France, or England) could have left us cold, were it not for the attempts made by the Tibetan "exile government" to anchor the existence of an "independent Tibetan nation" in the distant past and present it as a historical fact since the darkest period of prehistory. Actually, these concerns in no way deterred the 14th Dalai Lama, during his appearance before the European Parliament in Strasbourg, from dating the "founding" of his "nation" together with Tibetan "independence" to "the year 127 B.C."3 An amateur historian such as Klemens Ludwig, the German journalist and Dalai Lama admirer, also follows his idol here without the slightest hesitation. He too asserts that "western time counting" dates "the actual start of Tibetan history to the year 127 B.C." "At that time, King Nyatri Tsenpo laid the foundation of a significant dynasty in the Yarlung valley."4 There is no "historical trace" of the "first eight kings of the Yarlung dynasty", but this does not bother an ideologically hazy observer of history, not even when "legend says that they (...) descended directly from the heavens" and "returned there after death."5 Is that why there are no gravestones? Dating the first Tibetan kingdom to an exact year, around eight hundred years before the first written and historically still unreliable chronicles, is considered by Klemens Ludwig to be unproblematic, even though he himself ultimately admits: "However, the Yarlung kings do not become historically tangible (!) until the early 7th century. Under King Namri Songtsen the influence of the dynasty extended beyond the Yarlung valley."6 Eight whole centuries after the mythical first king and forefather of Tibetan "independence," the Tibetan rulers had "influence" over an entire "valley"?!

Furthermore: didn't David-Néel, who knew a fair amount about the early history of Tibet, write that the "Tibetans never formed a completely homogenous nation" and that, at the time of Songtsen Gampo in the 7th century, there were "more than one hundred different Tibetan tribes" who often fought with one another?7

Deshayes, the Dalai Lama-friendly but comparatively more serious Tibet historian than Klemens Ludwig, also guards against such uncritical (and naive) treatment of historical facts when he emphasises: "In response to the question about the origin of their people and their kingdom the Tibetans, who live so close to the heavens, always answered with myths and legends." He mentions several contradicting stories that come from different religious traditions. In the Bön tradition, for example, the first king's name was Öde Gungyel or Öde Purgyel. According to another legend, the first king – as per Ludwig – was called Nyatri Tsenpo. "Buddhist historians" (and not "western time counting!") fixed his "arrival in the earthly world to the year 127 before our time" and "based on academic calculations." As per the same tradition, this king had magical powers: armour that put itself on, a sword and a lance that fought by themselves. He could return at any time back to the heavens from where he descended thanks to a cord made of light, a so-called silver string, which connected him to the sky. When he died, he transformed into a rainbow before making his final ascension.8

As we can see, the Dalai Lama's appearance before the European Parliament had more of a story time session than a history lesson. What can we otherwise expect from a church dignitary and his court? It is to be feared that most of the EU delegates failed to notice the difference.

As it primarily applies to early history, the meagreness and unreliability of the written sources that were emphasised by Grunfeld is of less concern to us. The same cannot be said of the following: in the 19th and, above all, in the 20th century the political-ideological polarisation that resulted from rival powers battling for influence in the region hindered, according to Grunfeld, a view of things that was not influenced by interests. And indeed: Great Britain and the United States were (or are?!) a faction in the Tibetan conflicts. They were, at different times, directly involved on the ground, also from a military perspective. With the USA, in the context of the Cold War, indirectly also their allies in the East (Taiwan) and West. Impartiality from political observers and even historians, if they have internalised the Cold War front lines or are even continuing this war against China, is hardly to be expected.

A few further problems are also to be added:

– The fact that all written Tibetan sources come from a society where only very few people could read, even fewer could write and all those who were literate belonged to the high clergy and aristocracy implies a very specific view of things: all reported events are automatically perceived from the perspective of these social groups. That of most Tibetans, who were farmers and shepherds performing compulsory labour, is not reflected. The same applies to contemporary witnesses from the rows of Tibetan exiles who, in their majority, belong to the earlier elite. Grunfeld also refers to this.

– Most western Tibetologists were, and are, religious scholars, orientalists, or cultural anthropologists; their interest (and their support) was, and is, generally in Tibetan Buddhism, whether because they themselves are committed to this religion, or because they generally have a positive attitude towards religions, religious practices, and institutions. Even Patrick French, the leading "Tibet" activist, noted during a conference of the International Association for Tibetan Studies how much the (mainly western) Tibetologists, both the academics and their students, "focus on the apolitical and ethereal": "I had noticed that out of nearly 230 papers submitted, more than a hundred dealt with religion, a hundred with matters such as linguistics, education, art, literature, medicine, law, social sciences and botany, and only twenty-four with diplomatic history, political history or political science; there was no hint of economics."9

The fact that the perspective of most people in the western world is unilaterally determined by propaganda claims from Tibetan exiles has, according to Grunfeld, another cause: "Those who do not read the Chinese press (the vast majority of the populations of the world) have no access to Chinese positions, however poorly presented they may be." In this regard, he criticises the western media who used the material with which the Tibet Information Network in London bombarded them "unquestioningly,"10 and cites an American study from 1992, which concluded that almost all journalists are woefully ignorant of Tibet11 and report overwhelmingly in the Dalai Lama's favour.12 The historian summarised: "In the public relations war, China is monumentally outclassed." 13

The situation in Europe is by no means better when it comes to knowledge about Tibet, and the most absurd claims and "reports" from the Tibet scene are willingly disseminated in the media. For example, Goldner cites14 a dpa report also published by the taz (on 7th May 2002), where it was stated that the "senior-ranking Tibetan religious leader Rinpoche" had been arrested in Sichuan due to contact with the Dalai Lama. Rinpoche is a common title, comparable with the Christian "reverend," and by no means a name. False journalistic assertions cited by Goldner such as: the Dalai Lama had to flee from Tibet at the age of seventeen (taz, 7/10/1987) – he was actually twenty-four – or: the Potala is a "1,300-year-old cultural monument" (taz, 20/12/1994) – it comes from the 17th century – show, even when they only apply to details, the incredibly frivolous manner in which even "serious" and "left-wing" media handle the data and facts.15

The truth and justness of something certainly do not depend on who can afford the cleverest image consultants, the most expensive lawyers, and the most unreliable journalists! Reporting in western media, not just about Tibet but also China in general, is a "serious" or "dark chapter" as Heinrich Harrer would probably express it. A scientific study commissioned by the Heinrich Böll Foundation on the image of China conveyed by German media came to a clear conclusion that was shameful for the German media landscape. Throughout the year 2008, 8,766 reports "with a connection to China" in "six print media (the daily newspapers FAZ, SZ and taz and the weekly publications SPIEGEL, Focus and ZEIT)" plus "information programmes shown on public service television" were evaluated. The scientists' findings: In a "multitude of media reports" the "issue is not examined closely"; rather "socially inherent ideas and clichés about the country" are adopted "without reflection." More than half of the reports were shaped by "normative derogatory images of China," for example as a "'supporter of rogue states,' a 'climate sinner,' a 'cheap producer', a country with an ungovernable 'hunger for raw materials.'" The study also identified an ongoing dissemination of mainly "extremely" simplistic and "narrow clichés" by the German media. Seemingly positive images (China as an "attractive growth market" and "interesting production location") are only found in the "business sector." There are also "clear blind spots" in the selection of issues addressed and "central areas such as social issues or education, science & technology" are "almost completely excluded." The "massive focus" on "minority and territorial questions such as Tibet (11,2%)" or "the human rights situation (3,9%)" appear to be oversized "in light of the neglect" of other issues such as "urgent social questions (1,8%)" in China. Equally problematic is "economic reporting," which is "excessively" concentrated "on German companies and their interests, statements and actions." Overall, the selection of themes is "often determined by news factors such as conflict potential, negativity and focus on the elite," whereas in general "well-founded analyses of internally important developments are left out."16

Notes

1 Fabrice Midal, Tibetische Mythen und Gottheiten: Einblick in eine spirituelle Welt, From the French by Rolf Remers, Berlin, Theseus Verlag, 2002, p. 117 2 See also Laurent Deshayes, Histoire du Tibet, Librairie Arthème Fayard, 1997, p. 48 3 Cited from Goldner, Dalai Lama, p. 131 4 Klemens Ludwig, Zweitausend Jahre tibetische Geschichte, In Franz Alt et al., Tibet, p. 56 5 Ibid. p. 57 6 Ibid. p. 57-58 7 David-Néel, A l'ouest barbare de la vaste Chine, In Grand Tibet et vaste Chine, Récits et aventures, Librairie Plon, 1994, p. 768 8 See also Deshayes, Histoire du Tibet, p. 41-48. See also F. Midal, Tibetische Mythen und Gottheiten, p. 12, who talks about the "mythological origin of the ruling dynasties" and "events that have a religious tinge but cannot be historically documented" and R. A. Stein: Die Kultur Tibets, Berlin 1993, p. 44, which states: "These figures are purely conventional" and: "These early chronicles have in no way been strictly historically recorded (...) The rulers and their fortresses certainly date back to the 6th century, thus the tradition has relegated them to the mythical time of the first celestial king." 9 French, Tibet Tibet, p. 277-278 10 A. Tom Grunfeld: The Making of Modern Tibet, Revised edition. Armonk/New York and London: M.E. Sharpe, 1996, p. 239 11 Ibid. 12 Grunfeld, The Making... p. 239; he refers to Jude Carlson: Tibet in the News, in BCAS 24:2 13 Grunfeld, p. 240 14 Goldner, Dalai Lama... p. 415 – dpa is the Deutsche Presse-Agentur (German News Agency); taz (Tageszeitung) a major German newspaper. 15 See also Goldner, Dalai Lama... p. 409 16 http://www.boell.de/downloads/bildungkultue/Zusammenfassung_Thesen_China_Studie.pdf (accessed on 21/09/2011)

3 More than one thousand years ago: Chinese culture for a kingdom of barbaric warriors

Silk originally comes from India.

The fact that she was the fourth wife of King Songtsen Gampo is just as much ignored as the Buddhist missionary work of the Nepalese Princess Bhrikuti Devi.

The Potala had been burned and looted by the Dzungar Mongols in the accompanying civil war. (...) there is no escaping the fact that the principal patron of restauration of the modern Potala, the symbol of Tibetan nationalism that falls from a million campaign leaflets, was the man known as Superior Manjushri, who loved and guided sentient beings to good deeds: the Emperor of China.

If the Dalai Lama claims that a Tibetan nation existed in a grey past, he naturally does so to give his goal of detaching Tibet from China a historical foundation. Equally, anyone campaigning for a Tibet that is independent from China will unilaterally emphasise the autonomy of Tibetan culture and belittle, or even completely deny, all influences coming from China. Then, in the heat of the moment, India inadvertently becomes the country which discovered or invented silk and, who knows, also porcelain, paper, tea culture and chopsticks.

The culture of the Tibetans of course differs, in some areas even considerably, from that of the Han Chinese. It is the well-known story of the glass that, depending on the interest and viewpoint of the observer, is either half-empty or half full. The fact that there were strong influences and impulses from the more civilised kingdom of the Hans from a very early stage cannot seriously be denied. From Tibet's earliest history close political and, primarily, cultural contacts developed. Despite its particular geographic location, Tibet was by no means shielded against external influences. The initial contacts between the Tibetans and Han Chinese were rather unpleasant, as they were in the form of Tibetan raids, attacks, and lootings. In Jacques Gernet's The Chinese World, the first western academic history of China, he wrote about the "mountain people of the Himalaya massif and its peripheral regions": "The warlike nature" of the "Tibetans, Qiang people or Tanguts, Jyarung, Nashi or Mo-so etc." was expressed "in attacks on caravans and raids of arable land belonging to the residents." "Throughout the course of history, they spread themselves out towards the east, into the modern provinces of Kangsu, Sichuan and Shaanxi (...)."4 Ever since, the Tibetans have been perceived by the Han Chinese as particularly brave and warlike; the similarities with other nomadic peoples such as the Huns and Mongolians are clear.

The rooftops of the Jokhang Temple in Lhasa (Photo: Antoine Taveneaux, 2009)

The Chinese mainland and Tibet have had close political and cultural relationships since the early 7th century. At that time (in 641) Songtsen Gampo, the first king of a uniform Tibetan state, married the Chinese princess Wencheng (also: Wen Tcheng). At the time of the Tang dynasty, Buddhism was the state religion in China and China was the richest and most developed country in the world. The bride brought a magnificent statue of Buddha Shakyamuni with her to Lhasa, which to this day is kept "in the most holy of all temples, the Jokhang." "The religious gift shows that the first Buddhist influences came to Tibet not from India, but rather from China."5 Incidentally, the renowned western Tibetologist Tucci6 did not believe in Songtsen Gampo's marriage to a Nepalese princess, as is assumed by many historians.7 Be that as it may, the Chinese princess has enjoyed ever since a disparately higher degree of popularity in Tibet. The fact that Songtsen Gampo may also have had other wives makes little difference.

For what was even more important than the Buddhism that the princess had in her luggage at the time were the many Chinese craftsmen and artists, architects, teachers, cooks, carpenters, and painters who came with her to Tibet. According to a few reports, the princess also brought the knowledge and use of butter, tea, barley, and beer, as well as medical and astrological knowledge into her new homeland.8 When another Chinese princess, Tsing-tcheng, married a Tibetan king (Khride Tsang, 704-755) in 710, she also brought musicians and dancers, balls of silk and brocade as well as the spinning wheel with her.

Up until then, Tibetans probably only wore animal furs, skins and felt. Now natives were sent to China to learn the art of manufacturing paper and ceramics and other handicrafts.9 Songtsen Gampo encouraged sending the sons of chieftains to Changan (Xi'an), the capital of China at the time,10 for their education and upbringing. During the Tang era, there were no fewer than one hundred and fifty official visits between the two capitals and eight contracts were concluded, while "Tibet was absorbing Chinese culture."11 Even Deshayes admits: "The relationships with China bring with them a refining of the customs for the king's surroundings, which until then were unknown to the Tibetans with their coarse manners. Porcelain replaces pottery, ink and paper are used for the new writing, silk dresses emerge, whereas Bön medicine and astrology are enriched through Chinese knowledge and new irrigation techniques are introduced."12 Uli Franz also writes: "Through princess Wencheng, Chinese customs came into fashion in Lhasa. The Tibetan aristocracy found pleasure in silk and jade and learned how to use chopsticks."13 1,300 years later Père Huc, a French missionary, reported on the Tibetans' admiration for the Chinese princess that was expressed, for example, in a "festival of flowers" in Kumbum Monastery.14 For her part, David-Néel refers to a popular Tibetan epic about the princess that, in terms of its profile and popularity, is only slightly inferior to the "national epic" about King Gesar. It deals with the tests that Lhunpo Gara, the Tibetan emissary, had to pass in order for the Chinese Emperor to hand over his daughter Wencheng, who bears the Tibetan name Pumo Gyatsa (essentially "young Chinese princess"), as a wife for Songtsen Gampo.15 As a consequence: if the Tibet activist Ludwig plays down the role of the Chinese princess, his motives for doing so are clear; the facts, however, speak for themselves.

The strong cultural influences coming from China are also shown in the reports from Europeans, even those who visited the "independent" Tibet, after the 13th Dalai Lama had temporarily driven out representatives of the central state and murdered, detained or drove into exile their Tibetan followers. At the end of the 19th century in Tibet, A. H. Savage Landor describes such a Tibetan lord as "a singular looking person, dressed in a long dress made of green silk, with a Chinese pattern" and with a head covering "as worn by Chinese officials,"16 and Tibetan officers who "wore Chinese hats."17

David-Néel reports that she was invited to a Tibetan New Year festival in 1916 by a high-ranking lama: "We ate in a Chinese style, which is a very high accolade in Tibet."18 Ernst Schäfer writes, "Despite their purely Tibetan character the big feasts that filled the best part of the day", and to which ministers, "notables", and anyone of "rank and name" invited the members of the SS expedition, "were undoubtedly of Chinese origin." "This was not only expressed in the choice of meals, but primarily also in the fact that the best cooks in Lhasa who could mutually be borrowed are sons of the middle kingdom."19 Heinrich Harrer correspondingly reports of a first invitation from "Bönpos," high-ranking Tibetans: "We had a wonderful meal of Chinese noodles."20 He and Aufschnaiter marvelled at "the skill" with which the Tibetan hosts "handled their chopsticks."21 He later reported again from Lhasa that the Tibetans brought them a "splendid Chinese supper"22 or that he often saw there "wonderful Chinese" tea services that were "several hundred years old."23 During festivities he describes tents "draped with silks and brocades"24 and elegant Tibetans wearing "glossy yellow silk robes."25 Many Han Chinese were at that time back in Lhasa and Harrer even finds a good word for them when he notes that they liked to "marry Tibetan woman to whom they make model husbands," unlike the Nepalese.26

Alexandra David-Néel even discovered (Han) Chinese marks in the most holy centre of Lhasa, in the heart of Tibetan architecture, culture and religion, when she states, "For the main it was Chinese painters and art lovers to whom we owe the decorating of the Potala and the Jokhang, the holiest temple."27 In addition, "the upper terrace with its Chinese pavilions and their elegant, sparkling roofs," which are the first thing people notice upon their arrival in Lhasa, dominates the vast Potala palace, the symbol of Lhasa and the whole of Tibet.28

Notes

1 Alt, Tibet wird bald frei sein, In Alt/Ludwig/Meyer, Tibet. Schönheit, Zerstörung, Zukunft, p. 51 2 Klemens Ludwig, Zweitausend Jahre tibetische Geschichte, In: Franz Alt et al.: Tibet, p. 59 3 French, Tibet Tibet, p. 104. See also the comment (1) in Luciano Petech, China and Tibet in the XVIIIth Century: History of the Establishment of the Chinese Protectorate in Tibet, Second, revised edition, Leiden, E.J.Brill, 1972, p. 77 4 Jacques Gernet, Die chinesische Welt: Die Geschichte Chinas von den Anfängen bis zur Jetztzeit, With 40 black and white panels, 16 images in the text and 31 maps and plans, Frankfurt am Main, Suhrkamp Taschenbuch Verlag, First Edition 1998, p. 25 5 Uli Franz, Gebrauchsanweisung für Tibet, Munich, Piper Verlag, 2007 (revised new edition), p. 49 6 Also per Deshayes, p. 49 7 See also Grunfeld, The Making... comment p. 271 8 See also Grunfeld, The Making... p. 35. See also the "legend of the origin of Lhasa," which states: "No less than the Chinese princess Wen Cheng suggested, which seemed strange at the time, to build the Jokhang in the middle of the lake, which covered the plain of Lhasa." (Helmut Uhlig, Tibet: Ein verbotenes Land öffnet seine Tore, Bergisch Gladbach, 1988, p. 61) 9 Information from Han Suyin, Lhasa, the Open City: A Journey to Tibet, Frogmore, St Albans, Herts, Triad Paperbacks, 1979, p. 24 ff. 10 See also Grunfeld, p. 35 11 Grunfeld, p. 37 12 Deshayes, Histoire du Tibet, p. 55-56 13 Franz, Gebrauchsanweisung, p. 49 14 See also Han Suyin, Lhasa,Open City, p. 25, who refers to M. Huc, Travels in Tartary, Tibet and China, London, 1856 15 David-Néel, A l'ouest barbare de la vaste Chine. In Grand Tibet et vaste Chine, p. 762 ff. 16 Arnold Henry Savage Landor, La route de Lhassa: À travers le Tibet interdit (1897), Paris, Libella (Phébus libretto), 2010, p. 51 17 Ibid. p. 91 18 A. David-Néel, Wanderer mit dem Wind: Reisetagebücher in Briefen 1911-1917, Published by Detlef Brennecke, Wiesbaden, Heinrich Albert Verlag in the Erdmann edition, p. 309 19 Ernst Schäfer, Das Fest der weißen Schleier: Begegnungen mit Menschen, Mönchen und Magiern in Tibet, Durach, Windpferd Verlagsgesellschaft, 1988, p. 52 20 Heinrich Harrer, Seven Years in Tibet, p. 49 21 Ibid. p. 49 22 Ibid. p. 115 23 Heinrich Harrer, Sieben Jahre in Tibet... p. 169. These sentences are missing in the English edition. 24 Heinrich Harrer, Seven Years in Tibet... p. 153 25 Ibid. p. 154 26 Ibid. p. 156. Nothing can be seen here of the Chinese conceit or even master race attitude towards the Tibetans of which the "Free Tibet" scene accuses the Chinese. 27 David-Néel, Mein Weg durch Himmel und Höllen: Das Abenteuer meines Lebens, From the French by Ada Ditzen, With an introduction by Thomas Wartmann, Frankfurt am Main, Fischer Verlag, 8th edition 2012, p. 274 28 Ibid. p. 278. – L. Petech finds that there are few mutual cultural influences in the areas of religion and literature. Yet in the "small things" of life, there was a considerable, almost always unilateral influence on Tibetan culture by the Han Chinese. He states the language (borrowed words), painting, attire of the nobility and the eating culture of the upper class. See also Petech, China and Tibet in the XVIIIth Century, p. 260-263

4 Common history: the Mongolian, Ming, and Manchu emperors

Two Chinese viceroys with a guard of 1,000 soldiers are based in Lhasa and are replaced by other ones every three years. The Emperor of China is acknowledged as the overlord of the country; appointments to the highest offices in the state are made on his order, and all important matters are first reported to the court in Peking. But the country's internal government lies completely in the hands of the natives. In general, the Chinese are limited to the capital and the people of Tibet, excluding those in Lhasa, hardly feel the pressure of a foreign power.

For the federal government and the entire community of states it has been clarified that, under international law, Tibet is part of China.

The close cultural and dynastic relationship in the early days of Tibetan history did not prevent there being constant military disputes between the powerful Tibetan kingdom, founded by Songtsen Gampo, and the China of the Tang. The Tibetans even once succeeded in conquering the former capital of the Tang, Chang'an (modern day Xi'an).

With the Tang dynasty, a first formal contract was concluded as early as the 9th century and called the contract "of uncle and nephew."2 Buddhist monks on both sides negotiated it to end military conflicts. In 832, the text was sculpted into a column and can still be seen in front of the Jokhang in Lhasa.3

The following era is described in Chinese historiography as the time of the "five dynasties and ten states" from which the Song dynasty (960-1279) emerged. Their rulers were so focused on military threats in the south, west, and southwest that they had little concern for Tibet. The relationships were limited to occasional payments of taxes from individual Tibetan tribes to the Chinese capital and defeating uprisings in Tibet and the surroundings.4

When Muslim conquerors invaded India at the start of the 13th century they encountered, particularly in Bengal, supporters of Buddhism whom they forced to convert. The frightened Tibetan elite, who had since turned back to Buddhism, were looking around for powerful allies. At around the same time the Mongolian warriors of Dschingis Khan (1162-1227) were conquering the parts of China that correspond to the modern provinces of Gansu and Qinghai. To avert a Mongolian invasion of their territories and win an ally against Muslim expansion the lamas, looking for protection and an alliance, sent representatives to the Khan.

It eventually came to this when the abbot of the most significant monastery in Tibet at the time visited, together with two of his nephews, the grandson of Dschingis Khan, Godan, in Liangzhou. That abbot from Sakya Monastery, Sakya Pandita alias Kunga Gyaltsen (1182-1251), bowed to the Mongolian Khan by acknowledging his rule over Tibet and agreeing to make regular tribute payments. When powerful aristocrats in Lhasa rejected this deal, Godan sent troops to Tibet in 1251 and then appointed clerics to the most important secular offices. His successors, who were in the meantime sitting on the Chinese dragon throne (Kubilai Khan and his Mongolian successors, are described in China as the Yuan dynasty), and the Tibetan lamas continued the "priest and patron" relationship that connected them. Kubilai Khan gave the Sakya monk Phagpa (Lodo Gyaltsen, 1235 or 1239-1280), a nephew of the aforementioned Sakya Pandita who "arrived in Peking in 1253," the title of "imperial tutor" (dishi) and not only appointed him as ruler of the Tibetan provinces of Ü-Tsang, Kham and Amdo,5 but also gave him "general leadership of all religious communities within the kingdom." A lama called Senge rose to become the "all-powerful favourite of Kubilai Khan." He "got carried away with financial speculations and excessively collecting money and became guilty of lootings and countless murders."6

After the conquest of southern China, in 1277 another Tibetan monk called Yanglianzhenjia, "who, like Senge, achieved fame through his crimes,"7 became the leader of the newly created religion authority in Hangzhou in southern China. Grunfeld writes: "For the Sakya monks the enormous wealth and power showered upon them by the Mongols led to internal dissention, resulting in the murder of a chief lama by his own minister."8

Meanwhile, the Yuan Emperor was organising things in the west of the kingdom from Peking by "uniting the mosaic of religious and secular principalities and introducing a central power" as well as "appointing governors." From 1288, a political council (xuanzheng), appointed by Kubilai, administered religious and secular matters in Tibet.9

For Chinese historians, it is therefore beyond doubt that Tibet belonged to China during the time of the Yuan dynasty. How else would the emperors in Peking have been able to organise the administration there, name governors and collect tributes? How would Tibetan Buddhist lamas otherwise have been able to occupy the highest positions of power throughout China? Anyhow, the secular power of the highest lamas at the time came from the Emperor, i.e. the central government of China.10

Yet some people in the western world have a clever objection to this: the sixteen emperors of the Yuan dynasty were not Han people, not "ethnic Chinese," but rather Mongolians! As such, their kingdom was not China and modern day China cannot refer to it. Through this cheap argumentative conjuror's trick, it is possible simply to erase several centuries of Chinese history.11 What is to stop us from being similarly creative with European history? For example, with English history: after the Battle of Hastings England (i. e. the country of the Angles and Saxons) and the English kingdom no longer existed but instead it was a French-Norman country, a kind of Great Normandy. Consequently, the Hundred Years War was a French civil war and Joan of Orleans, so beloved by Le Pen, was a naive virgin from northern France who went to war not against English invaders but rather against her own people. Or with Spanish history: it wasn't the Spanish who once built and ruled over a world empire but possibly Austria or Switzerland because Philip I of Spain, known as "The Handsome," and the subsequent monarchs from the House of Habsburg were in no way ethnic Castilians. Moreover, what about the German Empire? Were there not at one time members of the House of Luxembourg sitting on the throne of the Holy Roman Empire of the German nation? Finally: wasn't Catherine the Great German, Hitler Austrian, and Stalin Georgian?

The argument that the Yuan Emperors were no ethnic Chinese but rather Mongolians turns a blind eye, due to ignorance or Eurocentric arrogance, to the significant fact that the Chinese were, and are, one of the oldest and most important cultural nations in the world. In the case of China, in no way did the foreign conquerors' language, writing, technology, and culture prevail, unlike, for example, in the regions conquered by the Romans (Gaul, Iberian Peninsula) or the Spanish colonies in Central America and South America. Rather, the nomads from the steppe, whether the Mongolians or later the Manchu, largely took over the language and writing, science and technology, traditions, and customs i.e. the entire highly developed culture and civilisation of those who had initially been defeated. Thus, an independent author such as Helmut Uhlig, for example, emphasises the "fact" that "for the sake of their imperial office" the "rulers from foreign peoples – primarily Mongolia and Manchu" "not only relinquished their ancestral names, but also their nationality, to meet the requirements for accession to the throne." The holder of the imperial seal "became spiritually Chinese. The land assimilated the powerful ones from its surroundings."12 Moreover, China has defined itself from its early history as a multi-ethnic state and, from a historical perspective, the Han people themselves are a mixed race (just like the Germans or French etc.).

At the time of the Ming dynasty, which replaced the Yuan, the Emperor's relationships with the Tibetan elite and its supremacy remained unchallenged, even though the Chinese reign was more "symbolic,"13 as western historians are happy to emphasise. (Also in the European Middle Ages, the reign of the kings or emperors over the duchies and counties in their countries was generally more "symbolic" and based on the feudal oaths and oaths of allegiance of the powerful local rulers, rather than on direct administrative and military control of the territory by the monarchs).

In 1408, the Ming Emperor Chengzu extended an invitation to Tsongkhapa, the founder of the new Gelugpa sect. The disciple who represented him, Djamyang Tchödje Shakya Yeshe became a favourite of the Emperor.14

"In 1409, Emperor Chengzu included the Tibetan prefects among the public officials in his domain and gave them a seal that confirmed their position."15 The "Sera Monastery was founded as a monastic university in 1419 and maintained close relationships with the Chinese Ming dynasty until the 17th century. Yet the contact between the abbot of Sera and the Emperor of China created tensions within the order and stirred up competition between the monastic universities of Sera and Drepung."16

Regardless of whether the Chinese reign over Tibet under the Ming Emperors was merely "symbolic": for the time of the Chinese Qing dynasty (from the early 18th century), which "brought the country (Tibet) a sense of internal political stability that was rare in its history,"17 the direct and effective rule of China is undisputed. This had been preceded by a time of renewed power struggles and civil wars within Tibet, during which the different sects and noble cliques united with Mongolian tribes to fight for power and privileges.18

In 1720, a Chinese army drove the Dzungar warriors out of Tibet. The Emperor's troops were warmly welcomed by the Tibetans and treated the local populace "with great moderation," as a western missionary reported.19 "On 24th of April 1721, a delegation sent by the Emperor delivered the official recognition to the Dalai Lama and on that occasion handed over the major state seal," which was inscribed "in the three languages of Manchu, Mongolian and Tibetan." The office of regent (Desi) was abolished and a council of ministers (Tibetan: bka' shag, Kashag) was created. "The chairman and his deputy were appointed by the Emperor. Tibet was now under the direct sovereignty of the empire."20 The eastern Tibetan province of Kham was integrated into Chinese Sichuan, with the Yangtze River as the new border. An imperial garrison of 3,000 men remained in Lhasa.

When the chairman of the Council of Ministers was murdered by the ministers (Tibetan: bka' blon, Kalön) in 1727 (his deputy escaped) and new unrest broke out, the Emperor again sent an army to restore law and order.21 The powers of the Dalai Lama, who belonged to the conspirators and was therefore initially banned, were limited to the spiritual realm. "To prevent new unrest, the Emperor strengthened the position of Chairman of the Council of Ministers (Prime Minister), and the former deputy was appointed to the office. However, he was assigned two ambans, Chinese residents, who reported directly to the Emperor."22

From this point, and for almost two centuries the ambans, a kind of Chinese high commissioner, were "authorised to conduct government business alongside the Dalai Lama and Panchen Lama." All Tibetan officials had to present their concerns to them for a ruling. They alone were responsible for "border defence, taxes, state finances" and they alone were entitled to report to the Emperor in Peking. They controlled the local Tibetan administration and had control over the troops stationed in Lhasa.23 The Emperor also ordered the creation of boundary demarcations along the borders with India and Nepal. The amban was tasked with performing an inspection of these borders and the border troops every year.

The amateur historian, Dalai Lama propagandist and professed astrologer Klemens Ludwig deliberately ignores a large part of the powers of these representatives of the Chinese central authority in Tibet and distorts their true role when he calls them "envoys" (the choice of words is anything but coincidental!) and merely concedes: "The ambans soon became a powerful force in Tibet. They controlled the entry of foreigners and influenced the Dalai Lama's discovery. In this way, they ensured that the tenth, eleventh and twelfth Dalai Lamas were chosen by lots."24 That was it. We can compare this account with what a credible historian writes. Grunfeld confirms in full the power of the ambans, also described by Kollmar-Paulenz, who were by no means mere envoys: They "were considered on a par with the Dalai and Panchen Lamas" but actually had more power than they had: they alone were "in absolute charge of financial, diplomatic, and trade matters." The two highest lamas no longer had any direct contact to the imperial court, but rather "all correspondence had to go through the ambans."25

Between 1727, when the office of High Commissioner for Tibet was created, and the collapse of the Qing dynasty in 1911, there were more than 100 ambans in succession, who (co-) ruled on behalf of the Chinese Emperor.

The golden urn lottery to determine the high "incarnations" was neither an initiative of the lamas nor the ambans; the Emperor himself decreed it for the Tibetan and Mongolian Buddhists in 1792. "To avoid Mongolian and Tibetan aristocrats manipulating the reincarnation of major living Buddhas" two golden urns were erected at the time, one in the Jokhang Temple in Lhasa and the other in the "Peking Lama Temple (Yonghe gong)." When determining the reincarnation of a living Buddha (such as the Dalai and Panchen Lamas), the lot with the name of the selected candidate (in each case, there were three candidates who had been suggested beforehand by authorised high lamas) was drawn from the urn. The ambans monitored the process in Tibet. "Furthermore, those who had the right to disclose the location of a reincarnation were forbidden from referring to children who were close family relatives of the deceased, a Mongolian Khan, high-ranking princes, nobles or military supreme commanders. Subsequently, there were repeated attempts to circumvent these unpopular imperial rules, particularly the lottery, but the imperial court did not deviate from them and rebuked all breaches." From the Qing dynasty to the time of the Republic of China, from thirty-nine reincarnation lines from the three schools, Gelugpa, Kagyupa and Nyingmapa, more than seventy living Buddhas were determined by drawing lots from the Golden Urn.26

Subsequently, both the Dalai Lamas and the regents drew their own powers from the Chinese Emperor who, alongside spiritual rule, had transferred political rule over Tibet back to the Dalai Lama on 7th February 1751; the strength of the ambans' position remained the same. David-Néel confirmed what had been the case for more than two centuries: "Where the clergy is concerned, the Dalai Lama had to be acknowledged by the Chinese government to be appointed to his office. On the day of his inauguration he had to bow before a portrait of the Emperor as a symbol of his vassalage. The same was true for the Panchen Lama in Shigatse."27

When the Kashag (a kind of council of ministers in the local Tibetan government) decided, after "the death of the 7th Dalai Lama on 22nd March 1757," to appoint a regent who was to exercise secular rule until the 8th Dalai Lama had been found and reached legal age, he was confirmed by the Emperor and, when he abdicated, he handed over to the young Dalai Lama "secular power with the imperial seal on 21st July 1781." After the successful invasion of the Nepalese Gurkhas in 1788, the Emperor again "divested" the rather incompetent church dignitaries of their "governing powers" and reappointed a regent.28

Around the same time, the imperial officials also brought "some experts" to Lhasa "to build Tibet's first mint."29 The silver coins minted there bore the inscription "Qianlong exchequer" on both sides and in Tibetan and Chinese.

Very little changed in Tibet during the 19th century; its affiliation to China was not questioned or disputed by either side before the last quarter of the century. However, the international environment in southern and eastern Asia was changing: European colonialism and imperialism enjoyed its heyday, if this poetic term can be applied to a somewhat repulsive growth, and expressions such as "gunboat diplomacy" and "opium wars" were added to the historian's vocabulary.

Before turning to this historical issue, allow me to draw a conclusion and some related comments: in view of Tibet's affiliation to China – if not without interruption since the 13th century (Yuan dynasty), as presented in Chinese historiography, at least historically undeniable, factually, and legally, since the early 18th century – we can only wonder at the perspective and historical understanding of some western politicians and authors. Even more so because their countries often played an active and inglorious role in weakening, dividing and exploiting China in the 19th and 20th century. Moreover: anyone in Germany, for example, who questions the historical justification of the Chinese claims to Tibet should perhaps remember that a federal state such as Schleswig-Holstein has only belonged to Germany since 1864 at the earliest, the year of the Prussian-Austrian victory over the Danes; it was not recognised under international law until 1920. Saarland did not become part of the Federal Republic of Germany until 1st January 1957. In France, Jean-Luc Mélanchon, presidential candidate for the Left Front, rightly reminds the "Free Tibet" followers in his country that Tibet has indisputably belonged to China for much longer than Nice, for example, has been part of France.30

The US American senate leaned particularly far out of the window: on 23rd May 1991, it adopted for the first time a declaration in which they called Tibet "an occupied country." If we remember that the imperial Chinese ambans (co-) ruled in Lhasa for more than half a century before the USA even came into existence, and that a large part of the current territory of this USA31 was not annexed until much later, during a long process, and through conquests, war, deception, breach of contract and the genocide of native Americans, the presumptuousness and brazenness (or even ridiculousness) of such a declaration is all too apparent.32

When, in 1950, the People's Republic of China restored also de facto the control over Tibet, which the preceding weak governments had lost for a while, the march of the Chinese troops was not even discussed in the UN. After the Lhasa uprising and flight of the Dalai Lama, the UNO discussed the situation in Tibet in October 1959 but failed to reach any decision even though, at the time, the western powers still refused to give the People's Republic of China its legitimate seat in the United Nations and clung to the fiction of a "national China" on the island of Taiwan.

Ever since, most countries in the world have entered diplomatic relations with the People's Republic of China and thus acknowledged Chinese sovereignty and China's existing borders.

We really must remember: neither the League of Nations, nor the UN, nor individual countries such as the USA, Great Britain or India ever officially acknowledged Tibet as an independent state. Not even at a time when China was not yet (again) an important subject but rather a largely powerless object in world history.

However, the following realisation, which we shall substantiate in detail further on with statements from contemporary witnesses and historians, is more important than legal considerations: the few decades of a Tibetan de facto "independence" were in no way a golden age of freedom. They were rather an era of imperialist interference, political and social standstill, maladministration, aristocratic and clerical oppression, heightened exploitation and taxation, economic decline, continued obscurantism, blatant injustice, political intrigues, attacks, murders, war and civil war.

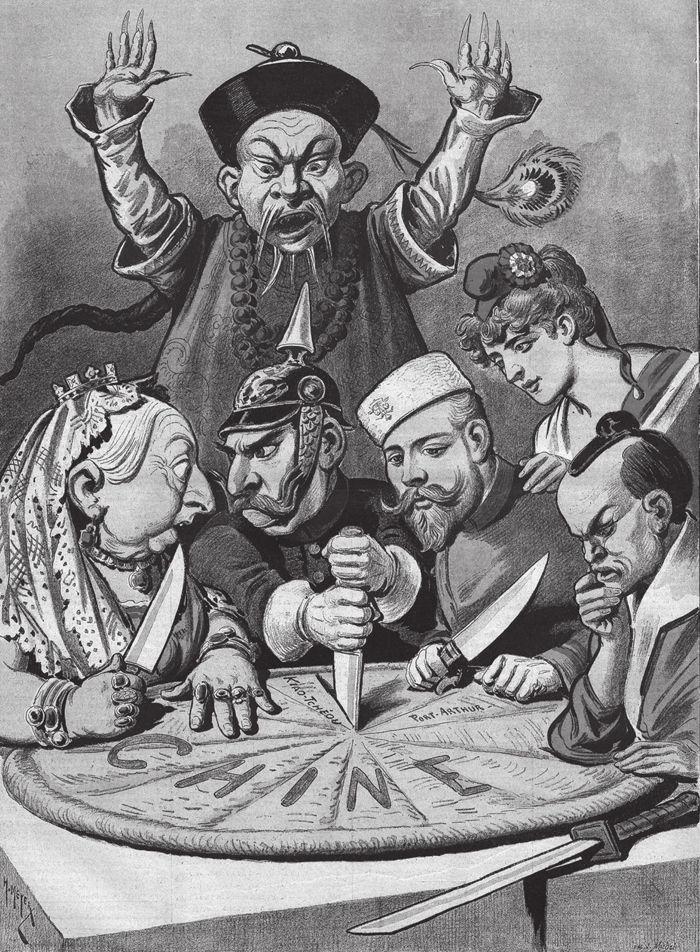

"En Chine: Le gâteau des Rois et... des Empereurs" – French political caricature from the late 1890s. The traditional French Epiphany cake stands for China, which is being divided between Queen Victoria (Great Britain), the German Emperor Wilhelm II., Nikolaus II. from Russia, the French Marianne, and Emperor Meiji from Japan. A stereotypically presented official of the Qing dynasty tries to stop them but is powerless. The caricature depicts the imperialist efforts against China at the time. From a supplement in Le Petit Journal from 16th January 1898. (Source: Bibliothèque nationale de France)

Notes

1 From a report from the first British traveller in Tibet to the British Governor General of Bengal, Warren Hastings: George Bogle, Im Land der lebenden Buddhas: Entdeckungsreise in das verschlossene Tibet 1774-1775, With a contribution from Sven Hedin, Published by Wolf-Dieter Grün, Stuttgart, Thienemann, Edition Erdmann, 1984, p. 274-275. No English original available. 2 The "uncle-nephew" principle (khü-bdon) determined for a long time the succession of offices in the Tibetan Gelugpa monasteries. The abbot or high-ranking dignitaries handed down their office to a nephew shortly before their death. See also Deshayes, p. 97 3 See also Grunfeld, p. 36-37 4 See also ibid. p. 37 5 Also Deshayes, p. 105 6 Jacques Gernet, Die chinesische Welt, p. 327; see also Deshayes, p. 105 and Grunfeld, p. 39 7 Gernet, Die chinesische Welt, ibid. 8 Grunfeld, The Making... p. 39, see also our chapter on the "criminal history" of Tibetan Buddhism in Free Tibet? 9 Deshayes, p. 107 10 See also the admission in the book from Blondeau/Buffetrille, which they conceived as a riposte from western pro-Dalai Lama Tibetologists to a Chinese white paper on the issue of Tibet: "Tibet's relationships with the Mongolian rulers of the Yuan dynasty are not limited to the connections between religious masters and secular patrons (chöyön), as the Tibetans sometimes claim." Blondeau/Buffetrille, Le Tibet est-il chinois?, Paris, Albin Michel, 2002, p. 35. – However, this is repeatedly claimed in western pro-Dalai Lama publications, as in Claude Arpi, The Fate of Tibet: When Big Insects Eat Small Insects, New Delhi, Har-Anand Publications, 1999, p. 65: "The Priest-Patron relationship continued to be the main feature of Tibet's external relations with the Manchu and Mongolia during the following centuries, until the fall of the Manchu in 1911." 11 Like in Françoise Robin, Clichés tibétains: Idées reçues sur le Toit du monde, Le Cavalier Bleu, p. 50. She confirms that Tibet was under the "military and political authority" of the Yuan Emperor, but disputes – note the wording – that "the Mongolian Yuan dynasty (1271-1368) saw itself as Chinese." Ms. Robin possibly doesn't know that even (Outer) Mongolia was seen by its larger northern neighbour as "Chinese" until deep into the 20th century. In May 1924, the young Soviet Union acknowledged Outer Mongolia as part of China in a "general convention." 12 Uhlig, Tibet: Ein verbotenes Land... p. 9 13 Per Deshayes, Histoire du Tibet... p. 121 14 See also ibid., with the names I have kept the spellings used by Deshayes. 15 Ibid. 16 Franz, Gebrauchsanweisung für Tibet, p. 113 17 Karénina Kollmar-Paulenz, Kleine Geschichte Tibets, Munich, Verlag C.H. Beck, 2006, p. 130 18 See also our chronology in A. Ettinger: Free Tibet? 19 Grunfeld: The Making... p. 45 20 http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dalai_Lama; accessed on 13.02.2013. – See also the corresponding chapter in Grunfeld: "Tibet as part of China," p. 44. See also the admission from Blondeau/Buffetrille, p. 56: "In 1721, Tibet's fate had been sealed for a long time, as Desideri correctly identifies. From a tributary state outside of the actual Chinese territory it was now defined as an integral part of China." 21 See also Grunfeld, The Making... p. 45: "to restore peace." – Petech calls the Chinese Tibet military campaign in 1728 "a simple military promenade" (no fighting occurred). (Luciano Petech, China and Tibet in the XVIIIth Century: History of the Establishment of the Chinese Protectorate in Tibet. Second, revised edition. Leiden, E.J. Brill, 1972, p. 145) 22 http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dalai_Lama; accessed on 13/02/2013 23 Kollmar-Paulenz, Kleine Geschichte... p. 130 and p. 126 24 Klemens Ludwig, In Franz Alt et al., Tibet, p. 66 25 Grunfeld, The Making... p. 46. – Oskar Weggel, who claims to present and discuss "Beijing's arguments" objectively, intentionally chooses the equally imprecise and unclear formulation that the "Manchurian" (!) ambans were "granted rights to vote on countless matters." It is thus easier for him to maintain the claim asserted in the corresponding sub-heading that China has "no 'historically grounded claim'" on Tibet." Academically objective? Rather blatant and crude... (See also: "The political Right and Left in the controversy about the Tibet problem", In Mythos Tibet: Wahrnehmungen, Projektionen, Phantasien, Published by the Art and Exhibition Hall of the Federal Republic of Germany Ltd., Bonn, in collaboration with Thierry Dodin and Heinz Räther, Cologne, Du Mont, 1997, p. 150 ff.) 26 Information and quotes from: http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Goldene_Urne and http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dalai_Lama, both accessed on 13/02/2013 27 David-Néel, Le vieux Tibet face à la Chine nouvelle, In: Grand Tibet et vaste Chine: Récits et aventures, Librairie Plon, 1994, p. 965 28 http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dalai_Lama; accessed on 13/02/2013 29 Grunfeld, The Making... p. 47 – Bogle reported (around 1775): "There are no mints in Tibet. Payments are made in Chinese and Tatar silver, in small bags with gold dust or in the coins of earlier Rajahs from Kathmandu and Patan..." (Bogle, Im Land der lebenden Buddhas, p. 207) 30 Nice and its region did not finally become part of France until 1860 (contract of Turin between Napoleon III. and the King of Sardinia-Piemont, Victor Emanuel II.), as did Savoy (Savoie and Haute Savoie). 31 The regions to the west of Mississippi, Florida, New Mexico, Texas, Colorado, Arizona, Utah, Nevada, California, Alaska, not to even mention Hawaii. 32 Under "Tibet," US-American elected representatives understand the "Greater Tibet" claimed by the Dalai Lama that, in part, never belonged to the political Tibet co-(governed) by the Dalai Lamas. See our later comments on this!

The Middle Kingdom lapsed from one weak position into the next, after the first opium war against the British (1839–1842) came the Taiping rebellion and a British-French military expedition (1851–1864) and then the Japanese-Chinese war (1894–1895). Particularly the British Empire from the Indian subcontinent and the former Russian tsardom from the north were interested in Central Asia.

Namely, China was threatened from all sides.

(...)

The region (around the port of Tsingtao) seemed, as Ferdinand von Richthofen recommended to Bismarck in 1882, not just capable of becoming a 'German Hong Kong,' but rather a 'gateway' to China as a whole. The Germans had acquired mining and railway rights in Shantung for this. Such concessions were comparably easy to wrest from the Chinese, weakened by the opium wars and the dispute with Japan and threatened from all sides. England, France and Russia managed at the same time, and in a similar way, to establish 'bridgeheads' in the 'Middle Kingdom,' which was also compelled by the USA to offer an 'open door' for all kinds of industrial and capital investments.

For a correct and, primarily, deeper understanding of Chinese positions, Chinese politics, and Chinese relationships a minimum of historical recollection is indispensable. Here also our media barely meet their actual mandate of informing and educating. Anyhow, there is hardly any demand for historical knowledge in our fast-moving society, even in relation to European history and, in European schools, history has long been one of the most unpopular and "uncool" subjects. In contrast to many modern Europeans, let alone Americans, the Chinese are a nation who are very aware of their history. Yet China's attitude (in no way only that of its Communist leadership) on the Tibet issue has a great deal to do with the more recent (and older) history of the country. We therefore cannot avoid expanding our perspectives and, for a short period, turning our attention away from regional, Tibetan events and towards the larger Chinese and global political connections.

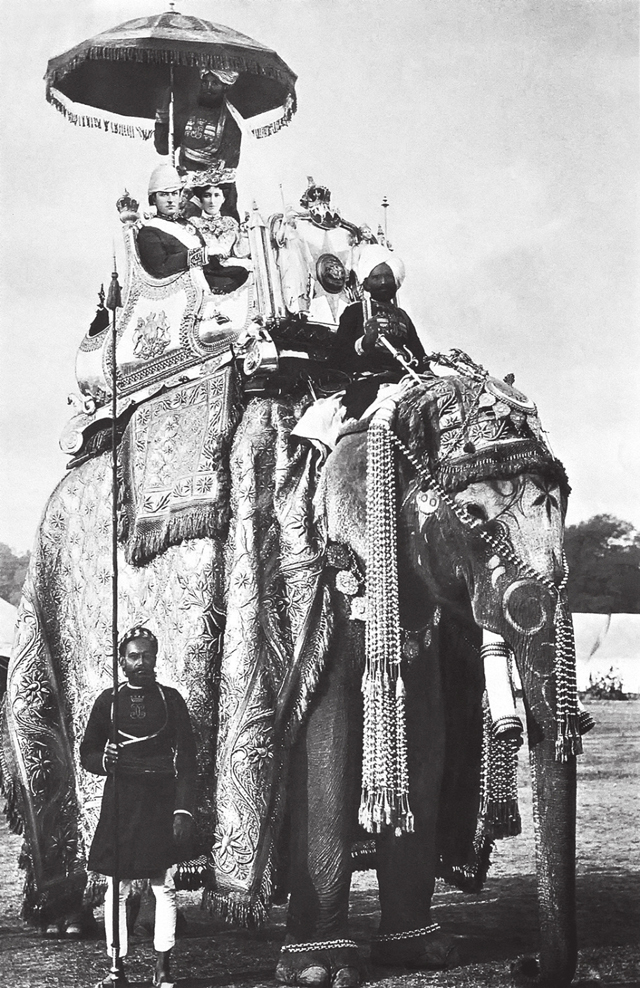

In her introduction to the "historical photo reportage" of China 1890-1938, Han Suyin describes the time around the transition from the 19th to the 20th century with such impressive and suitable words that I would like to quote her here: "1900. Europe is at the height of its imperial power and rules, as an absolute monarch, over the coloured world of Africa and Asia. European natural scientists write books in which they assert that the skull capacity in white people is larger than in Asians or black people. The superiority at all levels is God's will. (...) Vast riches from lootings in the subservient countries fill the banks in England and France. The 50-year Crown Jubilee of Queen Victoria was celebrated with great pomp. Maharajahs adorned with jewellery and oriental kings marched in the solemn procession like poor slaves. But in 1900 it comes to the 'Boxer Rebellion' in China, something happens with the rule of the white man. However, nobody understands it. The word 'rebellion' alone discloses the conquerors' attitude: it is lese majesty – a crime – if the lower races rebel against the better races, chosen by God. In this year, China fell into deep despair, decay, and bankruptcy. It was in a sorry state, a dying giant, decomposition had begun... since 1840, when Great Britain started a war against China to enforce opium as payment for silk and tea. China was plundered, robbed and at war with all of the European powers, who prised out of it concessions, privileges, compensation...Foreign garrisons in its towns, enclaves on Chinese soil that was no longer Chinese, gunboats on its rivers... and Europa's greed at the end of the 19th century knew no limits."3

Does Han Suyin's depiction unilaterally reflect the Chinese view of things? Western historians, even those with particularly conservative opinions, do not view recent European-Chinese history any differently: "During the entire 19th century, China was economically exploited by the European powers – primarily by Russia, Great Britain and France. Wilhelm II wanted the German Empire also to have its share and arranged for Kiautschou to be occupied as a naval base in 1898. Great Britain and Russia used this opportunity also to take some of China's ports. Chinese secret societies formed a riposte. In 1900, there was bloody unrest in Peking and a few northern Chinese provinces, which could only be put down through the brutal deployment of European and American troops." The emphasis lies in "brutal", as the "colonial war" against the "boxers" was excessively cruel, and the author speaks expressly about the "atrocities committed by German troops."4

The Bertelsmann chronicle of the 20th century5 recorded that, before the Boxer Rebellion "China" was "for many years a type of clearance region for the colonial powers" and lists the following Chinese "cessions of territory": "In 1884, Annam becomes a French protectorate. In 1887, China recognises the independence of the Portuguese port of Macau. In 1895, Formosa becomes Japanese. In 1895, Korea becomes 'independent' under Japanese influence. In 1898, Kiautschou is leased to the German Empire. In 1898, Port Arthur is leased to Russia. In 1898, the New Territories (Hong Kong) are leased to Great Britain. In 1898, Kwangschouwan becomes French. In 1899, the USA proclaims the 'open door policy,' a form of economic imperialism."6 The British invasion of Tibet in 1903 and the "independence" organised and controlled from British India around one decade later are seen by the Chinese as a continuation of this sequence, as part of an aggressive policy of carving up China by foreign colonial powers. A contemporary witness such as Alexandra David-Néel saw it in the same way. But let's stay for a while with the "Boxer Campaign" to create a clearer image of this policy.

On 15th August 1900, Peking was occupied by international "armies from colonial powers" (troops from Japan, Russia, Great Britain, USA, France, Germany, Austria, and Italy). The German Emperor Wilhelm II called them the "united troops of the civilised world." Some people still use such formulations today, whereby the very flexible term "free" is sometimes used instead of "civilised." The troops did in fact behave in an exceptionally "civilised" manner. For example, they "occupied" the imperial palace, "the Forbidden City, whereby irrecoverable works of art were destroyed. In the following weeks, the country shuddered under the atrocities committed by foreign soldiers."7 As the Germans stood out among everyone as being particularly "civilised" and "Christian," the Prussian field marshal Alfred Graf von Waldersee, who arrived in Tientsin in September, was awarded supreme command during the following "punitive expeditions."

The German atrocities were committed based on directives from above. On 27th July 1900 in Bremerhaven, Wilhelm II addressed his infamous "Hun speech" to German soldiers leaving for China: "Should you encounter the enemy, he will be beaten, no quarter will be given, no prisoners will be taken. Anyone who falls into your hands shall be forfeited. Just as the Huns thousands of years ago under their King Etzel established their reputation, one that even today makes them seem mighty, may the name Germany become known in China in such a way that no Chinese will ever again dare even to look askew at a German."8 The same Wilhelm also coined the silly racist word of the "yellow danger"....