More languages

More actions

| Great Yuan 大元 ᠳᠠᠢᠦᠨᠤᠯᠤᠰ | |

|---|---|

| |

| Capital | Khanbaliq |

| Dominant mode of production | Feudalism |

| Government | Monarchy |

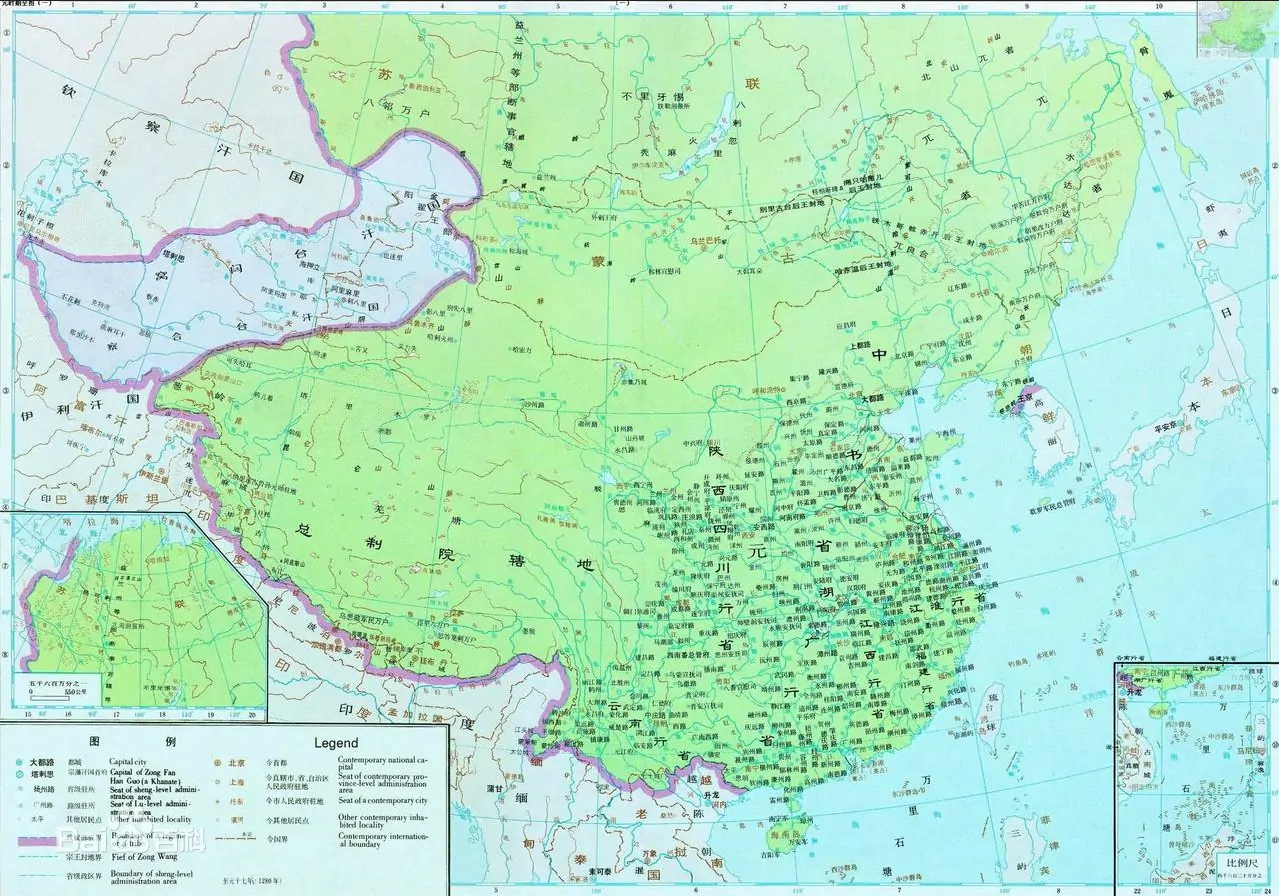

The Yuan dynasty, officially the Great Yuan, was a Mongol-led dynasty ruling over China.

Background[edit | edit source]

Mongol conquests[edit | edit source]

In 1227, 20 years after the Mongols had started their great raids, Temüjin died as he was bringing his forces back towards Mongolia. When he died, all the Mongol armies had to return home for another kurultai and elect their new leader. This process took over 2 years, and Temüjin's son, Ögedei, was elected as Chinggis Khan and presided over a second great age of conquest.[1]

It was under Ögedei's leadership that the Mongols ventured into China, destroying and incorporating the Jin state 1234 and move down into the Southern Song.[1]

Ögedei died in 1241, leaving a decade-long period of uncertainty after which the Mongol empire was divided among four of Temüjin's grandsons.[1]

Partition of the Mongol Empire[edit | edit source]

Batu Khan took over Russia and Ukraine, calling his territory the Khanate of the Golden Horde—the successors of which later became the Cossacks. Hulagu controlled Persia, with his descendants being known as the Ilkhan and converting to Islam which was the religion of Persia, emerging later as the Mughals (who ruled India until 1857). In the third territory in central Asia, Chagadai took over Samarkand, naming his holdings the Khanate of Chagatai. One of his descendants was Tamerlane, a great conqueror in the 15th century who almost conquered China. Finally, in China itself, Kublai became Khan and ruled over not only the Southern Song dynasty but Korea as well. He also made two attempts at invading Japan which never succeeded.[2]

This age of conquest was unprecedented; they brought together territories that had never been controlled by a single power in history. This created conditions which had never been seen before; for example, it became safe to travel all the way from the Mediterranean to the Pacific under the protection of the Mongols. There was much more interaction amongst different parts of East Asia, Eastern Europe and West Asia (the Middle East).[2]

Founding[edit | edit source]

When Kublai became Greath Khan in 1260, devoted his power to conquer all of China. This was not an easy endaveour for the Mongols and their cavalry tactics due to the hilly, mountaineous and wet nature of the South China plain with many river valleys. They brought in soldiers from other parts of the empire who had experience in urban warfare (both siege and in cities), particularly from Persia. They also learned to fight on rivers and waterways and for the first time really began to develop a naval component to their operations.[3]

The Mongols eventually succeeded in driving the Song emperor out of the capital at Hangzhou in the 1270s and by 1279, the last claimant to the throne was disposed of, dissolving the Song dynasty.[3]

China was thus unified again, although under a foreign ruler. In 1272, Kublai Khan had already established a new dynasty in China: the Yuan dynasty ("long-lasting" or "far-reaching"). This marked a clear change in Mongol administrative methods, that they needed to adapt to the realities of the country they had just conquered if they wanted to control it, but it was not entirely unique to China: they also did the same in Persia for example, adopting Islam.[3]

A capital was even established at Beijing, named Dadu (元大都, "Great capital"). The Mongols, being mostly nomadic, did not usually establish a permanent capital. Not all of the Mongols were happy with this however; some of the noblemen did not want to settlind down, and a portion of Mongols broke off from China to go back to their homeland, resuming their traditional lifestyle.[3]

Decline[edit | edit source]

Kublai Khan died in 1296, and so did the great age of the Mongols. While his descendants kept their territories, they eventually diverged from each other and took their own path integrating with their local cultures, breaking up the Mongol empire over time.[4]

After Kublai's death, there was a succession of mostly apathetic emperors. While the Yuan dynasty lasted another 80 years, they never really enjoyed the kind of power like Kublai had had. This gave rise to some developments that eventually contributed to the downfall of the Yuan dynasty.[4]

Power increasingly fell into the hands of Chinese officials, even at the imperial court. While they were theoretically employed solely as advisors, they came to have greater influence after Kublai's death. In 1313, the Mongols decided to reinstate the imperial examination system—a tremendous concession to the shi, as it formed the focal point of their identity.[4]

From there on, two problems developped:

- Great conflicts arose among the Mongol nobility. If someone's tribe began to stand out, the other families would band together to take them down (which Temujin and Kublai had managed to overcome and extinguish). After Kublai's death and several generations passed by, this aspect of their culture began to reemerge and when one Mongol noble began to be more powerful or competent, others came together to sabotage them. This internal sabotage rendered the Mongols a more or less neutral force in Chinese affairs.

- On the other hand, although the shi found back positions of influence, they tended to fall into factions loyal to particular nobles (likely because they lacked the base to form a unified force of their own), often at odds with each other.[4]

These two problems paralyzed the Yuan state, making it unable to respond to their natural and human challenges. Notably, a great plague struck China late in the 1340s, likely related to the plague that swept through Europe at the same time. In any case, the mortality rate was as high as 50% of the population in some places. This led to a variety of other problems such as insufficient revenues and labour-power to maintain big projects such as the river dikes, leading to flooding and more deaths through the elements or famine. Because of the way the Yuan court was structured by that point, neither local nobles nor the imperial court were able to respond to these events.[5]

Local authorities, in fact, tended to be so scared of the disease that they instead secluded themselves in their manors, hoarding as many resources as they could and never venturing out. The only "institutional" force that played a positive role in this period were the Buddhist monasteries, who provided shelter, food and medical care to people.[5]

This forced local popular movements to rise up, mostly centered around peasants, to seize the resources they needed—becoming bandits and rebels—to repair important infrastructure and avoid famines.[5]

Red Turban rebellion[edit | edit source]

Emperor Zhu Yuanzhang (朱元璋) lived as an intinerant ; while not a Buddhist monk per se, he traveled from monastery to monastery to receive shelter and food. There, he eventually started frequenting the peasant rebel groups that also relied on those services. He became involved with such a group called the Red Turbans, where his intelligence and military skills fairly quickly made him a leader in the movement.[6]

By the early 1360s, Zhu Yuanzhang had taken over the movement and softly repositioned it from a mystical motif (the movement saw itself as an apocalyptic upheaval thrown into the chaos of the plague) to using it to found a new dynasty, overthrowing the Yuan Mongols and placing himself at the head. He proclaimed this dynasty in 1368, calling it the Ming (明, Míng, meaning "bright"). However, while the dynasty was proclaimed, he had not defeated the Mongols yet.[6]

Zhu Yuanzhang took his various armies which had been consolidated in the Yangtze valley to the capital at Dadu. Upon their arrival, instead of fighting, the Mongols abandoned the city and retreated to the grasslands further north, letting Zhu Yuanzhang to take control of the empire. He then returned south and established his capital at Nanjing, leaving one of his sons in command of the old capital at Dadu against a possible Mongol invasion.[6]

Role of intellectuals[edit | edit source]

The very first challenge the Yuan under Kublai Khan faced was the administrative question. By that time, China was home to around 100 million people versus perhaps a million Mongols spread out over their entire conquered territories. There were also particular tensions between the Mongol conquerors and the traditional shi elite, who had resisted the conquerors for over 20 years, leading to resentment from the Mongols towards the Chinese elites. Finally, there was a cultural barrier: most Mongols were illiterate, and could not read classical Chinese, which furthered their distrust of the shi.[7]

The Mongols however could not entirely get rid of the shi as they could not effectively administer China without some access to the existing mechanisms of administration. Their solution was thus to import educated and experienced people from other parts of their territories who came to be known as the sèmù rén (色目人, "people with colored eyes"), reflecting their foreign nature.[7]

The semu ren were placed in official positions alongside the shi, but couldn't speak or read Chinese themselves, still requiring intermediaries. But with this system, the semu ren came to control the high-level decisions and the shi were relegated to clerical work. The shi found themselves in an undesirable position, as they had previously thought of themselves as being policy-makers and the best-suited people to control the affairs of the kingdom. Because of this new role, they began turning some their attention and energy into other kinds of activites, especially in art and literature. In painting for example, a whole genre of perseverance and endurance symbolism (such as rocks, bamboo shoots, blooming flowers, etc.) flourished in the Yuan dynasty.[7]

More significantly, they also began to write plays and popular dramas which were played all over the empire in public theaters, including in the capital at Dadu. These were historical dramas which drew on legends of the past and historical accounts. They often told stories that had to do with resistance to arbitrary authority and maintaining the purity of Han culture in the face of barbarian presence. Such topics were of course prohibited by the Mongols, but the censors did not catch these nuances and theater plays flourished under the Yuan.[7]

Marco Polo was himself a semu ren; born in Venice, he left in 1272 and travelled over land to the Yuan court with his father and uncle, eventually becoming a government employee in China for over 20 years before going back to his home city.[7]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Dr. Ken Hammond (2004). From Yao to Mao: 5000 years of Chinese history: 'Lecture 20: The Rise of the Mongols'. The Teaching Company.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Dr. Ken Hammond (2004). From Yao to Mao: 5000 years of Chinese history: 'Lecture 20: The Rise of the Mongols'. The Teaching Company.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Dr. Ken Hammond (2004). From Yao to Mao: 5000 years of Chinese history: 'Lecture 21: The Yuan Dynasty'. The Teaching Company.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Dr. Ken Hammond (2004). From Yao to Mao: 5000 years of Chinese history: 'Lecture 21: The Yuan Dynasty'. The Teaching Company.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Dr. Ken Hammond (2004). From Yao to Mao: 5000 years of Chinese history: 'Lecture 22: The Rise of the Ming'. The Teaching Company.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Dr. Ken Hammond (2004). From Yao to Mao: 5000 years of Chinese history: 'Lecture 22: The Rise of the Ming'. The Teaching Company.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 Dr. Ken Hammond (2004). From Yao to Mao: 5000 years of Chinese history: 'Lecture 21: The Yuan Dynasty'. The Teaching Company.