More languages

More actions

| Some parts of this article were copied from external sources and may contain errors or lack of appropriate formatting. You can help improve this article by editing it and cleaning it up. (November 2025) |

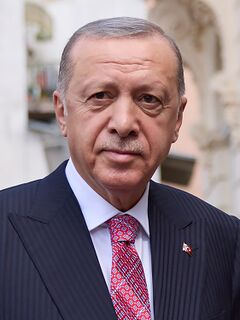

Recep Tayyip Erdoğan | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 26 February 1954 Beyoğlu, Istanbul, Turkey |

| Nationality | Turkish |

| Political orientation | Neoliberalism Imperialism Islamism Right-wing populism |

| Political party | Justice and Development |

Recep Tayyip Erdoğan (born 26 February 1954) is a Turkish far-right politician who has served as president of Turkey since 2014. Previously, he served as Prime Minister from 2003 to 2014 and as mayor of Istanbul from 1994 to 1998. Erdoğan is the cofounder and leading figure of the Justice and Development Party (AKP), leading the party since 2017, having previously served as leader from 2001 to 2014. The AKP is an organization combining Islamism, conservative liberalism, and neoliberal economy.

Under his leadership, Turkey transitioned from a parliamentary system to a centralized presidential regime characterized by executive dominance and declining institutional checks.[1] He is currently holding an unconstitutional third term due to controversial legal reinterpretations[2] and his dubious university diploma.[3]

Early life[edit | edit source]

Erdoğan was born in 1954 in İstanbul. He emerged politically within the Islamist National Outlook (Turkish: Milli Görüş) movement, becoming mayor of Istanbul in 1994. His brief imprisonment in 1999 elevated his status among conservative voters. In 2001, Erdoğan co-founded the AKP, framing it as a moderate split from earlier Islamist parties while maintaining continuity with their ideological outlook.[citation needed]

Premiership[edit | edit source]

The AKP came to power in 2002 amid economic crisis and political division. Erdoğan’s early period was marked by promises of democratization, European Union reforms, and economic stabilization. This phase allowed the AKP to build legitimacy among liberal segments and international institutions while simultaneously consolidating a loyal conservative base and expanding its influence within the state apparatus.[1]

During its ascent, the AKP initiated a strong neoliberal program that fundamentally restructured Turkey’s political economy in favor of capital. The party accelerated privatizations on an unprecedented scale, selling off state enterprises in energy, mining, transportation, and telecommunications to domestic conglomerates and foreign investors. This process dismantled public ownership and transferred strategic sectors into the hands of a newly empowered bourgeoisie closely tied to the AKP leadership. Labor rights were systematically weakened: unions faced restrictive legislation, strikes were routinely banned “for national security,” and precarious subcontracted work became the norm across both public and private sectors.[4][5][6]

Erdoğan was largely perceived as a reformist and relatively liberal-leaning figure during his early period. The 2013 Gezi Park protests began in response to the Taksim Pedestrianization Project and its destructive impact on the natural environment of Gezi Park. When demonstrators opposed the project, the AKP refused dialogue and rapidly deployed police forces against peaceful protestors, which escalated the situation into nationwide protests across Turkey. Erdoğan claimed that the uprising was a Soros-backed color revolution,[7] while independent reports and on-the-ground observations showed that the protests were an organic, spontaneous reaction of the population against the increasing autocratic tendencies of Erdoğan’s government.[8][9][10]

Presidency[edit | edit source]

After the Gezi Park protests, Erdoğan accelerated a decade-long shift toward autocratic rule. The collapse of the Kurdish peace process in 2015, intensified police operations in the southeast, and the government’s growing control over courts and media marked a decisive end to the AKP’s reformist image. The 2016 coup attempt provided the pretext for a sweeping state of emergency, enabling mass purges, the closure of critical media outlets, and the restructuring of state institutions under executive authority. In 2017, a tightly controlled referendum replaced the parliamentary system with a centralized, unchecked, unbalanced presidential regime, granting Erdoğan expansive decree powers and direct influence over the judiciary. Throughout the late 2010s and early 2020s, opposition leaders were imprisoned, elected Kurdish mayors were removed and replaced with state-appointed trustees, and electoral conditions deteriorated as pro-government media monopolized the public sphere. By 2023, Turkey had effectively transformed into a consolidated hybrid autocratic system centered on Erdoğan’s presidency, with sharply reduced civil liberties, politicized courts, and limited space for democratic opposition.[11][12][13]

Ongoing opposition crackdowns[edit | edit source]

In the aftermath of the 2024 local elections, the AKP experienced a historic electoral setback, falling to second place for the first time since its rise to power. The main opposition party, the CHP, secured a sweeping victory in major metropolitan areas through a successful left-wing populist campaign that reclaimed significant urban cities from the ruling bloc. Faced with the loss of political and economic control in key municipalities, Erdoğan began a new phase of intensified persecution targeting opposition-held local governments.[14]

While the appointment of state trustees to municipalities governed by Kurdish parties had long been a standard instrument of AKP rule, the extension of this practice to the country’s founding opposition party marked an escalation in autocratic consolidation. In March 2025, İstanbul Mayor Ekrem İmamoğlu—who had recently announced his presidential campaign—was detained and later imprisoned under the pretext of a corruption investigation. Although the government framed these actions as anti-corruption measures, no comparable inquiries were launched into the AKP’s own long-standing corruption scandals.[15][16][17]

The crackdown triggered protests centered in İstanbul’s Saraçhane—where İstanbul Municipality's HQ is—which briefly revived opposition mobilization but failed to achieve the scale or momentum of the 2013 Gezi Park uprising. By early 2025, the pattern of arrests, trustee appointments, and legal harassment against opposition leaders signaled a new stage of political repression, reinforcing assessments that Turkey had entered a deeply autocratic, if not openly fascist, phase under Erdoğan’s rule.[18]

"Family Year"[edit | edit source]

In 2025, Erdoğan expanded crackdown beyond the political sphere and into everyday social life by declaring a so-called “Family Year,” signaling a transition toward a more overtly reactionary moral governance resembling the cultural policies seen in Putin's Russia.[19] Although Erdoğan once claimed in 2002 that the rights of LGBTQ+ individuals should be protected,[20] his administration has since undergone a dramatic ideological regression. By 2025, state discourse centered on openly antagonizing LGBTQ+ communities, criminalizing their public existence, and framing them as threats to the nation and family.[19][21] The government introduced new restrictions on trans healthcare,[22] moved to enforce rigid gender norms with near-theocratic severity, and prepared a judicial package aimed at policing social behavior along conservative religious lines.[23] Women’s bodily autonomy faced further erosion as the state intensified control over reproductive rights, including a ban on elective Caesarean deliveries.[24][25] Through these policies, the Erdoğan regime sought to reverse decades of civil rights gains and entrench a socially conservative order that restricts personal freedoms and imposes its ideological vision on the entire population.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Barış Özkul (2025-03-24). "Turkey’s Authoritarian Turn" Jacobin. Archived from the original on 2025-08-12.

- ↑ "Presidential term limits don't apply to Erdoğan, top election body concludes" (2023-04-04). Bianet. Archived from the original on 2025-04-25.

- ↑ "Controversy over Erdoğan’s university degree reignited ahead of elections" (2023-03-24). Turkish Minute. Archived from the original on 2025-07-10.

- ↑ Erin O’Brien (2022-03-13). "In Erdoğan’s Turkey, Privatization Means Corruption and Collapsed Infrastructure" Jacobin. Archived from the original on 2025-05-17.

- ↑ K. Murat Yıldız (2021-05-03). "President Erdoğan: The world's biggest real estate agent" Duvar English. Archived from the original on 2025-06-25.

- ↑ "AKP’nin Milli Görüş gömleği, neoliberalizm ile deli gömleğine dönüştü" (2017-10-16). sendika.org.

- ↑ "Erdoğan'dan Kavala açıklaması: Bu adam Gezi olaylarının perde arkasındaydı" (2022-04-27). Gazete Duvar. Archived from the original on 2025-03-21.

- ↑ "Turkey: The Gezi Park Protests". Pen International. Archived from the original on 2025-05-06.

- ↑ "Boyun eğmeyenlerin büyük direnişi: İşte gün gün Gezi Parkı direnişi" (2013-06-06). soL haber. Archived from the original on 2024-05-31.

- ↑ Cemal Burak Tansel (2013-06-02). "The Gezi Park occupation: confronting authoritarian neoliberalism" openDemocracy. Archived from the original on 2025-09-24.

- ↑ "Turkey: Authoritarian Drift Undermines Rights" (2015-01-29). Human Rights Watch. Archived from the original on 2025-09-07.

- ↑ "Turkey a 'de facto dictatorship': Bertelsmann Stiftung Transformation Index" (2020-04-30). Duvar English. Archived from the original on 2025-04-28.

- ↑ "'Diktatör Erdoğan' ve 'Boyun Eğme' pankartları suç sayıldı: Esila Ayık dahil üç öğrencinin hapsi istendi" (2025-05-13). soL Haber. Archived from the original on 2025-05-14.

- ↑ Paul Kirby, Cagil Kasapoglu (2024-04-01). "Turkish local elections: Opposition stuns Erdogan with historic victory" BBC. Archived from the original on 2025-10-06.

- ↑ Barış Demir (2024-11-01). "Erdogan government arrests Kurdish CHP mayor in Istanbul" WSWS. Archived from the original on 2025-09-22.

- ↑ Barış Demir, Ulaş Ateşçi (2025-02-11). "Turkish government escalates crackdown against CHP and DEM Party" WSWS. Archived from the original on 2025-09-21.

- ↑ Barış Demir, Ulaş Ateşçi (2025-03-19). "Erdogan’s main rival, İstanbul mayor Ekrem İmamoğlu detained by police" WSWS. Archived from the original on 2025-09-21.

- ↑ Cihan Tuğal (2025-03-30). "The Unlikely Resistance in Turkey" Jacobin. Archived from the original on 2025-10-09.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 "Erdoğan targeted LGBTI+ individuals at the International Family Forum and declared the 2026-2035 period as the “Decade of Family and Population”" (2025-05-27). KaosGL. Archived from the original on 2025-06-15.

- ↑ "Erdoğan “Eşcinsel hakları güvenceye alınmalı” demişti" (2020-06-29). Bianet. Archived from the original on 2025-04-26.

- ↑ "Turkey’s year of family becomes ‘year against LGBTI+" (2025-03-06). Duvar English. Archived from the original on 2025-08-11.

- ↑ "Bakanlık, transların hormona erişimine 21 yaş sınırı getirdi" (2025-06-27). Bianet. Archived from the original on 2025-10-10.

- ↑ "Türkiye: Draft Law Threatens LGBT People with Prison" (2025-10-29). Human Rights Watch. Archived from the original on 2025-11-24.

- ↑ "Sağlık Bakanlığından karar: Planlı sezaryen yasaklandı". Rudaw. Archived from the original on 2025-04-20.

- ↑ "Turkey: Women's rights activists slam 'Year of the family'" (2025-02-01). DW. Archived from the original on 2025-06-30.