More languages

More actions

(Translated from The Great Soviet Encyclopedia, Vol. 35 (1937), pp. 214-216.) |

mNo edit summary Tag: Visual edit |

||

| (3 intermediate revisions by one other user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

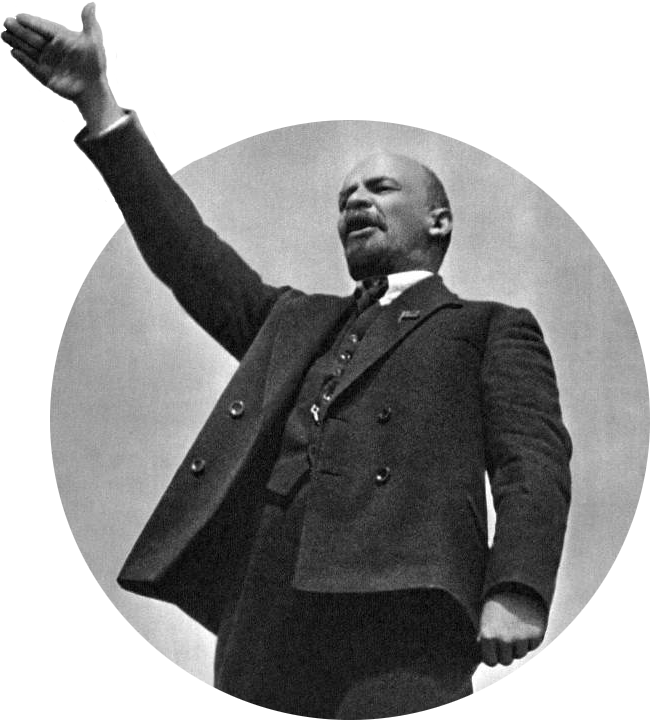

{{Message box/Externalarticlecleanup|date=September, 2022}}{{Infobox politician|name=Oliver Cromwell|image=Oliver Cromwell Portrait.jpg|birth_date=25 April 1599|death_date=3 September 1658|nationality=English}} | |||

Oliver Cromwell (1599-1658), | '''Oliver Cromwell''' (1599-1658), was an [[Kingdom of England (927–1707)|English]] general who would lead the 17th century [[English Bourgeois Revolution]], and would later assume the title of [[Commonwealth of England, Scotland and Ireland (1653–1659)|Lord Protector of England]]. Descended from the middle landed gentry of Geitingdonshire, located in Central England. Cromwell studied at Cambridge University, but did not graduate due to the death of his father. Having married the daughter of a London merchant, Cromwell settled on his estate and took up farming. As a member of [[Parliaments of the Protectorate|parliament]] from 1628, Cromwell joined the Puritan opposition in it. A decisive turning point in the political activities of Cromwell is associated with the convocation of the Long Parliament, where he was sent from the city of Cambridge. In it, Cromwell immediately took a prominent position as a radical Puritan leader, taking part in all the most important acts of this parliament: Cromwell demanded the abolition of the episcopate, insisted on bringing Strafford to trial, took an active part in drawing up the Great Remonstration of 1641, which formulated in detail the requirements of the [[bourgeoisie]]. With the outbreak of the [[English Civil War|civil war]], Cromwell energetically set about organizing military detachments that became part of the so-called Eastern Counties Association. Here the outstanding abilities of Cromwell quickly began to been seen as a military organizer. The forces that were recruited by him, mainly the yeoman of the eastern counties, and the detachments of the "zkelezpokolok," provided parliament with the first great victory over the royalists at the Battle of Marston More. In the future, Cromwell was entrusted with the reorganization of the entire parliamentary army. After the old [[Presbyterianism|Presbyterian]] generals were removed from command, Cromwell actually began to play a leading role in the parliamentary army; the new commander-in-chief, Fairfax, was entirely under the influence of his "lieutenant general." At the battle of Nesby, Cromwell inflicted a final defeat on the Royalist troops. With the defeat of the king and the beginning of a split within the parliamentary camp, the political role of Cromwell as the leader of the party of indispensable parties increased even more. Relying on the support of the entire parliamentary army, Cromwell in the spring of 1647 entered into a sharp conflict with the Presbyterian majority in parliament, which insisted on the demobilization of the army. In early August 1647, the army approached [[London]], and the Independents carried out the first purge of parliament (excluding 11 deputies). | ||

However, by this time, there was a stratification within the Independents themselves. From the end of August 1647, a new party of levellers was formed | However, by this time, there was a stratification within the Independents themselves. From the end of August 1647, a new party of levellers was formed, with which Cromwell led a sharp struggle, which led in the same year to the suppression of the leveling uprising. Having defeated the royalists for the second time in the so-called second civil war, Cromwell and his army by the end of 1648 became the master of the situation in the capital and throughout England. At that time, under the pressure of the revolutionizing masses and the leveling party, with which the Independents in 1648 were close again, Cromwell moved from [[Monarchism|monarchist]] to [[Republicanism|republican]] positions. Later on, he would order a purge of Parliament was carried out from Presbyterians who were trying to conclude a compromise with the king; in January 1649, [[Charles I]] himself was executed, after which a republic was established in England. The subsequent struggle of Cromwell with the levelers and the defeat of their organization in 1649, as well as an energetic policy of conquest — the campaigns against Ireland (1649) and [[Kingdom of Scotland (843–1707)|Scotland]] (1650-51), the publication of the Navigation Act in 1651, and the war with [[Republic of the Seven United Netherlands (1588–1795)|Holland]] caused by the latter — raised the general's prestige is high in the eyes of the bourgeoisie and the new [[Aristocracy|nobility]], who saw him as a fake defender of [[Private property|bourgeois property]]. The figure of Cromwell began increasingly to overshadow the Long Parliament, whose members by this time were exposed to obvious corruption. Relying on the officers' circles and the sympathy of the bourgeoisie, in 1653, Cromwell dispersed the remnant of the Long Parliament. After an unsuccessful attempt to rule through the Independent Convention (meeting of representatives from the Independent communities) Cromwell would, later that year, be proclaimed by his supporters the Lord Protector of England. | ||

The new constitution, worked out by the officers' council ("The Control Tool"), essentially introduced the monarchy, albeit in a disguised form. As a protector, Cromwell still became close to big capital, while at the same time taking a number of steps towards the interests of large landownership. Scotland was united with England in 1654; in the same year a victorious peace was concluded with Holland. In the following years, a number of profitable trade agreements were concluded with Portugal, France, Denmark, Sweden; in 1656 a new war with Spain began. In the interests of large landownership, a law of 1656 was passed to abolish feudal extortion and turn land into full ownership of landowners. Severely suppressing the performances of the royalists, Cromwell even more brutally suppressed the democratic movements, dealing mercilessly with the levellers, diggers, millenarians, Quakers and other extreme religious and political trends. An open military dictatorship was introduced in the country. The whole of England was divided into 11 military districts, headed by major generals, to whom the civil authorities were subordinate. In 1657, Cromwell's supporters in the new parliament offered him to accept the royal title, but under pressure from the officers, who feared the growth of opposition, Cromwell agreed to accept it; however, he permitted the restoration of the House of Lords and agreed to grant him the right to appoint his successor; as such he appointed his son Richard. Cromwell died | == Political leadership == | ||

The new constitution, worked out by the officers' council ("The Control Tool"), essentially introduced the monarchy, albeit in a disguised form. As a protector, Cromwell still became close to big capital, while at the same time taking a number of steps towards the interests of large landownership. Scotland was united with England in 1654; in the same year a victorious peace was concluded with Holland. In the following years, a number of profitable trade agreements were concluded with [[Kingdom of Portugal (1139–1910)|Portugal]], [[Kingdom of France|France]], [[Kingdom of Denmark|Denmark]], [[Kingdom of Sweden|Sweden]]; in 1656 a new war with [[Monarchy of Spain (1516–1700)|Spain]] began. In the interests of large landownership, a law of 1656 was passed to abolish [[Feudalism|feudal]] extortion and turn land into full ownership of landowners. Severely suppressing the performances of the royalists, Cromwell even more brutally suppressed the democratic movements, dealing mercilessly with the levellers, diggers, millenarians, [[Quakers]] and other extreme religious and political trends. An open [[military dictatorship]] was introduced in the country. The whole of England was divided into 11 military districts, headed by major generals, to whom the civil authorities were subordinate. In 1657, Cromwell's supporters in the new parliament offered him to accept the royal title, but under pressure from the officers, who feared the growth of opposition, Cromwell agreed to accept it; however, he permitted the restoration of the House of Lords and agreed to grant him the right to appoint his successor; as such he appointed his son Richard. Cromwell died in 1658. | |||

Combining — in the expression of Engels — | == Legacy == | ||

Combining — in the expression of Engels — “[[Maximilien de Robespierre|Robespierre]] and [[Napoleon Bonaparte|Napoleon]] in one person”, Cromwell played a progressive role, overthrowing the old rotten absolutist order. In a conversation with GD Wells, Comrade [[Stalin]] said: “Remember the history of England in the 17th century. Didn't many say that the old social order had rotted away? Perhaps, nevertheless, but it took Cromwell to finish it off by force? ". The activity of Cromwell in recent years has been of a narrow-class nature, being entirely subordinated to the interests of the big bourgeoisie and the landowners associated with it. Having seized power in the form of the dictatorship of Cromwell, the English bourgeoisie attacked democracy with repressions, which in the end led it itself to an inevitable compromise with the defeated feudal aristocracy. | |||

[[Category:History of England]] | |||

[[Category:Rulers of England]] | |||

[[Category:Military leaders during the English Civil War]] | |||

[[Category:Genocide perpetrators]] | |||

[[Category:Bourgeois revolutionaries]] | |||

{{DEFAULTSORT:Cromwell, Oliver}} | |||

Latest revision as of 13:11, 29 August 2023

| Some parts of this article were copied from external sources and may contain errors or lack of appropriate formatting. You can help improve this article by editing it and cleaning it up. (September, 2022) |

Oliver Cromwell | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 25 April 1599 |

| Died | 3 September 1658 |

| Nationality | English |

Oliver Cromwell (1599-1658), was an English general who would lead the 17th century English Bourgeois Revolution, and would later assume the title of Lord Protector of England. Descended from the middle landed gentry of Geitingdonshire, located in Central England. Cromwell studied at Cambridge University, but did not graduate due to the death of his father. Having married the daughter of a London merchant, Cromwell settled on his estate and took up farming. As a member of parliament from 1628, Cromwell joined the Puritan opposition in it. A decisive turning point in the political activities of Cromwell is associated with the convocation of the Long Parliament, where he was sent from the city of Cambridge. In it, Cromwell immediately took a prominent position as a radical Puritan leader, taking part in all the most important acts of this parliament: Cromwell demanded the abolition of the episcopate, insisted on bringing Strafford to trial, took an active part in drawing up the Great Remonstration of 1641, which formulated in detail the requirements of the bourgeoisie. With the outbreak of the civil war, Cromwell energetically set about organizing military detachments that became part of the so-called Eastern Counties Association. Here the outstanding abilities of Cromwell quickly began to been seen as a military organizer. The forces that were recruited by him, mainly the yeoman of the eastern counties, and the detachments of the "zkelezpokolok," provided parliament with the first great victory over the royalists at the Battle of Marston More. In the future, Cromwell was entrusted with the reorganization of the entire parliamentary army. After the old Presbyterian generals were removed from command, Cromwell actually began to play a leading role in the parliamentary army; the new commander-in-chief, Fairfax, was entirely under the influence of his "lieutenant general." At the battle of Nesby, Cromwell inflicted a final defeat on the Royalist troops. With the defeat of the king and the beginning of a split within the parliamentary camp, the political role of Cromwell as the leader of the party of indispensable parties increased even more. Relying on the support of the entire parliamentary army, Cromwell in the spring of 1647 entered into a sharp conflict with the Presbyterian majority in parliament, which insisted on the demobilization of the army. In early August 1647, the army approached London, and the Independents carried out the first purge of parliament (excluding 11 deputies).

However, by this time, there was a stratification within the Independents themselves. From the end of August 1647, a new party of levellers was formed, with which Cromwell led a sharp struggle, which led in the same year to the suppression of the leveling uprising. Having defeated the royalists for the second time in the so-called second civil war, Cromwell and his army by the end of 1648 became the master of the situation in the capital and throughout England. At that time, under the pressure of the revolutionizing masses and the leveling party, with which the Independents in 1648 were close again, Cromwell moved from monarchist to republican positions. Later on, he would order a purge of Parliament was carried out from Presbyterians who were trying to conclude a compromise with the king; in January 1649, Charles I himself was executed, after which a republic was established in England. The subsequent struggle of Cromwell with the levelers and the defeat of their organization in 1649, as well as an energetic policy of conquest — the campaigns against Ireland (1649) and Scotland (1650-51), the publication of the Navigation Act in 1651, and the war with Holland caused by the latter — raised the general's prestige is high in the eyes of the bourgeoisie and the new nobility, who saw him as a fake defender of bourgeois property. The figure of Cromwell began increasingly to overshadow the Long Parliament, whose members by this time were exposed to obvious corruption. Relying on the officers' circles and the sympathy of the bourgeoisie, in 1653, Cromwell dispersed the remnant of the Long Parliament. After an unsuccessful attempt to rule through the Independent Convention (meeting of representatives from the Independent communities) Cromwell would, later that year, be proclaimed by his supporters the Lord Protector of England.

Political leadership[edit | edit source]

The new constitution, worked out by the officers' council ("The Control Tool"), essentially introduced the monarchy, albeit in a disguised form. As a protector, Cromwell still became close to big capital, while at the same time taking a number of steps towards the interests of large landownership. Scotland was united with England in 1654; in the same year a victorious peace was concluded with Holland. In the following years, a number of profitable trade agreements were concluded with Portugal, France, Denmark, Sweden; in 1656 a new war with Spain began. In the interests of large landownership, a law of 1656 was passed to abolish feudal extortion and turn land into full ownership of landowners. Severely suppressing the performances of the royalists, Cromwell even more brutally suppressed the democratic movements, dealing mercilessly with the levellers, diggers, millenarians, Quakers and other extreme religious and political trends. An open military dictatorship was introduced in the country. The whole of England was divided into 11 military districts, headed by major generals, to whom the civil authorities were subordinate. In 1657, Cromwell's supporters in the new parliament offered him to accept the royal title, but under pressure from the officers, who feared the growth of opposition, Cromwell agreed to accept it; however, he permitted the restoration of the House of Lords and agreed to grant him the right to appoint his successor; as such he appointed his son Richard. Cromwell died in 1658.

Legacy[edit | edit source]

Combining — in the expression of Engels — “Robespierre and Napoleon in one person”, Cromwell played a progressive role, overthrowing the old rotten absolutist order. In a conversation with GD Wells, Comrade Stalin said: “Remember the history of England in the 17th century. Didn't many say that the old social order had rotted away? Perhaps, nevertheless, but it took Cromwell to finish it off by force? ". The activity of Cromwell in recent years has been of a narrow-class nature, being entirely subordinated to the interests of the big bourgeoisie and the landowners associated with it. Having seized power in the form of the dictatorship of Cromwell, the English bourgeoisie attacked democracy with repressions, which in the end led it itself to an inevitable compromise with the defeated feudal aristocracy.