More languages

More actions

m (Removed redirect to Second Five-Year Plan of China) Tag: Removed redirect |

No edit summary Tag: Visual edit |

||

| (11 intermediate revisions by 5 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

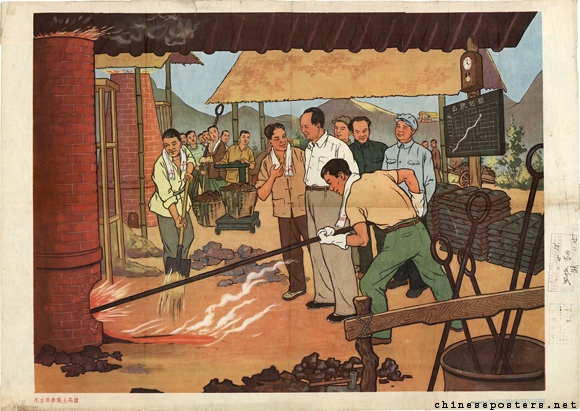

[[File:Great Leap Forward poster.png|thumb|Poster of [[Mao Zedong|Mao]] visiting a homemade steel furnace during the Great Leap Forward]] | |||

The '''Great Leap Forward''' (Simplified Chinese: 大跃进; Pinyin: Dà yuèjìn) was an economic and social campaign in the [[People's Republic of China]], introduced in 1958 as a part of the [[Five-year plans of China#Second Plan (1958–1962)|Second Five-Year Plan]]. | |||

The policies surrounding the Great Leap Forward created the conditions for [[Peasantry|peasants]], who had already [[Collectivization|collectivized]] land, to further collectivize. This led to the creation of large communes composed of thousands of people. Both industrial capacity and food security were advanced as a result of the Great Leap Forward and its policies.<ref name=":1" /> | |||

There were also policy failures and practices such as producing steel in small rural foundries, also known as [[backyard furnace|backyard steel furnaces]]. Mao admitted that policy errors occurred and took responsibility for them, but [[Imperial core|Western]] claims of mass starvation are widely exaggerated.<ref>[https://alphahistory.com/chineserevolution/mao-responsibility-great-leap-forward-1959/ MAO ON RESPONSIBILITY FOR THE GREAT LEAP FORWARD (1959)]</ref> | |||

== Famine == | |||

Western sources often claim that the largest famine in history took place during the Great Leap Forward. Official Chinese documents released after Mao's death put the death toll at 16.5 million, which may be exaggerated, while [[Bourgeois media|bourgeois]] sources claim that 30 or even 38 million people died. Other sources such as The China Quarterly (a CIA funded outlet) claim 50-60 million died.<ref>{{Web citation|author=Joseph Ball|newspaper=Monthly Review|title=Did Mao Really Kill Millions in the Great Leap Forward?|date=2006-09-21|url=https://mronline.org/2006/09/21/did-mao-really-kill-millions-in-the-great-leap-forward/|retrieved=2023-04-23|quote=U.S. state agencies have provided assistance to those with a negative attitude to Maoism (and communism in general) throughout the post-war period. For example, the veteran historian of Maoism Roderick MacFarquhar edited The China Quarterly in the 1960s. This magazine published allegations about massive famine deaths that have been quoted ever since. It later emerged that this journal received money from a CIA front organisation, as MacFarquhar admitted in a recent letter to The London Review of Books. (Roderick MacFarquhar states that he did not know the money was coming from the CIA while he was editing The China Quarterly.)}}</ref> | |||

Mao spoke on the subject of over-enthusiasm in the Great Leap Forward at the Wuchang Conference saying | |||

"In this kind of situation, I think if we do [all these things simultaneously] half of China’s population unquestionably will die; and if it’s not a half, it’ll be a third or ten percent, a death toll of 50 million. When people died in Guangxi, wasn’t Chen Manyuan dismissed? If with a death toll of 50 million, you didn’t lose your jobs, I at least should lose mine; [whether I would lose my] head would be open to question. Anhui wants to do so many things, it’s quite all right to do a lot, but make it a principle to have no deaths." <ref name=":0">{{Web citation|author=Joseph Ball|newspaper=Monthly Review|title=Did Mao Really Kill Millions in the Great Leap Forward?|date=2006-09-21|url=https://mronline.org/2006/09/21/did-mao-really-kill-millions-in-the-great-leap-forward/#en22|retrieved=2023-04-23|quote=In this kind of situation, I think if we do [all these things simultaneously] half of China’s population unquestionably will die; and if it’s not a half, it’ll be a third or ten percent, a death toll of 50 million. When people died in Guangxi [in 1955-Joseph Ball], wasn’t Chen Manyuan dismissed? If with a death toll of 50 million, you didn’t lose your jobs, I at least should lose mine; [whether I would lose my] head would be open to question. Anhui wants to do so many things, it’s quite all right to do a lot, but make it a principle to have no deaths.22 | |||

Then in a few sentences later Mao says: “As to 30 million tons of steel, do we really need that much? Are we able to produce [that much]? How many people do we mobilize? Could it lead to deaths?”}}</ref> | |||

A few moments later Mao continues "As to 30 million tons of steel, do we really need that much? Are we able to produce [that much]? How many people do we mobilize? Could it lead to deaths? ” <ref name=":0" /> | |||

It is true that agricultural production decreased in five years between 1949 and 1978 due to “natural calamities and mistakes in the work.” However, during 1949 and 1978, the per hectare yield of land sown with food crops increased by 145.9% and total food production rose 169.6%. During this period China’s population grew by 77.7%. On these figures, China’s per capita food production grew from 204 kilograms to 328 kilograms in the period in question.<ref name=":1">Guo Shutian ‘China’s Food Supply and Demand Situation and International Trade’ in ''Can China Feed Itself? Chinese Scholars on China’s Food Issue.'' Beijing Foreign Languages Press 2004.</ref> | |||

== Industrial Growth == | |||

In 1952, industry was 36% of gross value of national output in China. By 1975, industry was 72% and agriculture was 28%. It is quite obvious that Mao’s supposedly disastrous socialist economic policies paved the way for the rapid economic and industrial development of [[Reform and Opening Up]].<ref>M. Meissner, ''The Deng Xiaoping Era. An Enquiry into the Fate of Chinese Socialism, 1978-1994'', Hill and Wray 1996.</ref> | |||

Official Chinese statistics show that after the end of the Leap in 1962, industrial output value had doubled; the gross value of agricultural products increased by 35 percent; steel production in 1962 was between 10.6 million tons or 12 million tons; investment in capital construction rose to 40 percent from 35 percent in the First Five-Year Plan period; the investment in capital construction was doubled; and the average income of workers and farmers increased by up to 30 percent.<ref>''[https://books.google.com/books?id=AE8zAQAAIAAJ People's Republic of China Yearbook]''. Vol. 29. Xinhua Publishing House. 2009. p. 340. <q>The 2nd Five-Year Plan (1958–1962)</q> </ref> Additionally, there was significant capital construction (especially in iron, steel, mining and textile enterprises) that ultimately contributed greatly to China's industrialization.<ref>Joseph, William A. (1986). "A Tragedy of Good Intentions: Post-Mao Views of the Great Leap Forward". ''Modern China''. '''12''' (4): 419–457. doi:10.1177/009770048601200401. ISSN 0097-7004. JSTOR 189257. S2CID 145481585.</ref> | |||

Heavy industry grew a great deal in this period too. Developments such as the establishment of the Taching oil field during the Great Leap Forward provided a great boost to the development of heavy industry. A massive oil field was developed in China. This was developed after 1960 using indigenous techniques, rather than Soviet or western techniques. (Specifically the workers used pressure from below to help extract the oil. They did not rely on constructing a multitude of derricks, as is the usual practice in oil fields).<ref>W. Burchett with R. Alley ''China: the Quality of Life.'' Penguin, 1976.</ref> | |||

== More Reading/Videos == | |||

[https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Jw8VEwHUlJs Raymond Lotta Talking about the Great Leap Foward] | |||

== References == | |||

[[Category:Debunking myths]] | |||

[[Category:History of China]] | |||

Latest revision as of 21:53, 5 August 2023

The Great Leap Forward (Simplified Chinese: 大跃进; Pinyin: Dà yuèjìn) was an economic and social campaign in the People's Republic of China, introduced in 1958 as a part of the Second Five-Year Plan.

The policies surrounding the Great Leap Forward created the conditions for peasants, who had already collectivized land, to further collectivize. This led to the creation of large communes composed of thousands of people. Both industrial capacity and food security were advanced as a result of the Great Leap Forward and its policies.[1]

There were also policy failures and practices such as producing steel in small rural foundries, also known as backyard steel furnaces. Mao admitted that policy errors occurred and took responsibility for them, but Western claims of mass starvation are widely exaggerated.[2]

Famine[edit | edit source]

Western sources often claim that the largest famine in history took place during the Great Leap Forward. Official Chinese documents released after Mao's death put the death toll at 16.5 million, which may be exaggerated, while bourgeois sources claim that 30 or even 38 million people died. Other sources such as The China Quarterly (a CIA funded outlet) claim 50-60 million died.[3]

Mao spoke on the subject of over-enthusiasm in the Great Leap Forward at the Wuchang Conference saying

"In this kind of situation, I think if we do [all these things simultaneously] half of China’s population unquestionably will die; and if it’s not a half, it’ll be a third or ten percent, a death toll of 50 million. When people died in Guangxi, wasn’t Chen Manyuan dismissed? If with a death toll of 50 million, you didn’t lose your jobs, I at least should lose mine; [whether I would lose my] head would be open to question. Anhui wants to do so many things, it’s quite all right to do a lot, but make it a principle to have no deaths." [4]

A few moments later Mao continues "As to 30 million tons of steel, do we really need that much? Are we able to produce [that much]? How many people do we mobilize? Could it lead to deaths? ” [4]

It is true that agricultural production decreased in five years between 1949 and 1978 due to “natural calamities and mistakes in the work.” However, during 1949 and 1978, the per hectare yield of land sown with food crops increased by 145.9% and total food production rose 169.6%. During this period China’s population grew by 77.7%. On these figures, China’s per capita food production grew from 204 kilograms to 328 kilograms in the period in question.[1]

Industrial Growth[edit | edit source]

In 1952, industry was 36% of gross value of national output in China. By 1975, industry was 72% and agriculture was 28%. It is quite obvious that Mao’s supposedly disastrous socialist economic policies paved the way for the rapid economic and industrial development of Reform and Opening Up.[5]

Official Chinese statistics show that after the end of the Leap in 1962, industrial output value had doubled; the gross value of agricultural products increased by 35 percent; steel production in 1962 was between 10.6 million tons or 12 million tons; investment in capital construction rose to 40 percent from 35 percent in the First Five-Year Plan period; the investment in capital construction was doubled; and the average income of workers and farmers increased by up to 30 percent.[6] Additionally, there was significant capital construction (especially in iron, steel, mining and textile enterprises) that ultimately contributed greatly to China's industrialization.[7]

Heavy industry grew a great deal in this period too. Developments such as the establishment of the Taching oil field during the Great Leap Forward provided a great boost to the development of heavy industry. A massive oil field was developed in China. This was developed after 1960 using indigenous techniques, rather than Soviet or western techniques. (Specifically the workers used pressure from below to help extract the oil. They did not rely on constructing a multitude of derricks, as is the usual practice in oil fields).[8]

More Reading/Videos[edit | edit source]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Guo Shutian ‘China’s Food Supply and Demand Situation and International Trade’ in Can China Feed Itself? Chinese Scholars on China’s Food Issue. Beijing Foreign Languages Press 2004.

- ↑ MAO ON RESPONSIBILITY FOR THE GREAT LEAP FORWARD (1959)

- ↑ “U.S. state agencies have provided assistance to those with a negative attitude to Maoism (and communism in general) throughout the post-war period. For example, the veteran historian of Maoism Roderick MacFarquhar edited The China Quarterly in the 1960s. This magazine published allegations about massive famine deaths that have been quoted ever since. It later emerged that this journal received money from a CIA front organisation, as MacFarquhar admitted in a recent letter to The London Review of Books. (Roderick MacFarquhar states that he did not know the money was coming from the CIA while he was editing The China Quarterly.)”

Joseph Ball (2006-09-21). "Did Mao Really Kill Millions in the Great Leap Forward?" Monthly Review. Retrieved 2023-04-23. - ↑ 4.0 4.1 “In this kind of situation, I think if we do [all these things simultaneously] half of China’s population unquestionably will die; and if it’s not a half, it’ll be a third or ten percent, a death toll of 50 million. When people died in Guangxi [in 1955-Joseph Ball], wasn’t Chen Manyuan dismissed? If with a death toll of 50 million, you didn’t lose your jobs, I at least should lose mine; [whether I would lose my] head would be open to question. Anhui wants to do so many things, it’s quite all right to do a lot, but make it a principle to have no deaths.22

Then in a few sentences later Mao says: “As to 30 million tons of steel, do we really need that much? Are we able to produce [that much]? How many people do we mobilize? Could it lead to deaths?””

Joseph Ball (2006-09-21). "Did Mao Really Kill Millions in the Great Leap Forward?" Monthly Review. Retrieved 2023-04-23. - ↑ M. Meissner, The Deng Xiaoping Era. An Enquiry into the Fate of Chinese Socialism, 1978-1994, Hill and Wray 1996.

- ↑ People's Republic of China Yearbook. Vol. 29. Xinhua Publishing House. 2009. p. 340.

The 2nd Five-Year Plan (1958–1962)

- ↑ Joseph, William A. (1986). "A Tragedy of Good Intentions: Post-Mao Views of the Great Leap Forward". Modern China. 12 (4): 419–457. doi:10.1177/009770048601200401. ISSN 0097-7004. JSTOR 189257. S2CID 145481585.

- ↑ W. Burchett with R. Alley China: the Quality of Life. Penguin, 1976.