More languages

More actions

(Indigenous role) Tag: Visual edit |

m (corrections) Tag: Visual edit |

||

| (7 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

== Background == | == Background == | ||

Conflict between North and South over slavery began almost immediately after the [[Louisiana Purchase]] in 1803. The North officially abolished slavery in 1804, though using gradual emancipation laws that kept young Africans enslaved as late as the 1850s.<ref>{{Web citation|author=Nicholas Boston and Jennifer Hallam|newspaper=Thirteen PBS|title=Slavery and the Making of America|date=2004|url=https://www.thirteen.org/wnet/slavery/experience/freedom/history.html|retrieved=2023-09-04|quote=Pennsylvania passed its Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery in 1780. Yet, as late as 1850, the federal census recorded that there were still hundreds of young blacks in Pennsylvania, who would remain enslaved until their 28th birthdays.}}</ref> The industrializing North had little use for slavery, which was unprofitable for manufacturing. Unending streams of European immigrants to the North (in large part sourced by enclosure acts like those in Scotland in the early 1800s)<ref>{{Citation|author=Karl Marx|year=1853|title=The Duchess of Sutherland and Slavery|title-url=https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1853/03/12.htm|quote=As for a large number of the human beings expelled to make room for the game of the Duke of Atholl, and the sheep of the Countess of Sutherland, where did they fly to, where did they find a home? In the United States of North America.|city=New York City|publisher=New York Daily Tribune|mia=https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1853/03/12.htm}}</ref> provided a huge reserve army of labor cheaper than what it would cost to buy, care for, guard, and educate enslaved people. | |||

Even agricultural regions in the North were ill-suited to slavery, as wheat crops were seasonal and enslaved people would need vital needs provided year round. In the North, slavery wasn't abolished on a moral level, rather it was simply less economical than "free" labor from a reserve army of labor. This meant that the economic bases of the political estates in the North and South began to considerably diverge. The conflict between these political estates is characterized by the problem of whether slavery would expand to the new territories westward. | |||

As territories began to become states, these political estates maintained a balance with the [[Missouri Compromise]] in 1820. This legislation ruled that slavery would not spread north of the 36º 30' latitude line for the new territories and that an equal number of free and slave states would enter the union, guaranteeing an equal number of senators for the northern and southern estates. | |||

This political balance was once again disturbed by the acquisition of new lands westward, this time annexed from Mexico as a result of the [[Mexican–Statesian War|Mexican-Statesian War]]. The new western land demanded that the question over slavery should be settled in the Kansas and Nebraska territories in preparation for the building of railroads. The political conflict resulted in the [[Kansas-Nebraska Act]] of 1854, with its infamous "popular sovereignty" provision that directly contradicted the previous Missouri Compromise. The white men living in a territory would now themselves vote on becoming slave or free states. This resulted in the [[Bleeding Kansas]] border war, with pro-slavery "border ruffians" and anti-slavery forces flooding into the Kansas and Nebraska territories to sway the vote.<ref>{{Web citation|newspaper=United States Senate|title=The Kansas-Nebraska Act|url=https://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/minute/Kansas_Nebraska_Act.htm|retrieved=2023-09-04}}</ref> The guerrilla warfare between these forces, culminating in [[John Brown]]'s attempt at slave revolution in [[Harper's Ferry]] in 1859, soon exploded into full-blown civil war. | |||

In early 1861, several southern states of the [[United States of America|USA]] seceded to form the Confederate States of America. [[Abraham Lincoln]] succeeded [[James Buchanan]] as [[President of the United States]] in March. The CSA seized the army base at Fort Sumter, [[State of South Carolina|South Carolina]] in April 1861, beginning the war.<ref name=":0" /><sup>:133</sup> | In early 1861, several southern states of the [[United States of America|USA]] seceded to form the Confederate States of America. [[Abraham Lincoln]] succeeded [[James Buchanan]] as [[President of the United States]] in March. The CSA seized the army base at Fort Sumter, [[State of South Carolina|South Carolina]] in April 1861, beginning the war.<ref name=":0" /><sup>:133</sup> | ||

== Indigenous involvement == | == Indigenous involvement == | ||

Most of the Confederate officers had fought against indigenous nations in [[Settler colonialism|settler colonial]] wars.<ref name=":0" /><sup>:133</sup> The Union also oppressed indigenous peoples and took almost 500 million acres of their land with the Homestead and Pacific Railroad | Most of the Confederate officers had fought against indigenous nations in [[Settler colonialism|settler colonial]] wars.<ref name=":0" /><sup>:133</sup> The Union also oppressed indigenous peoples and took almost 500 million acres of their land with the [[Homestead Act|Homestead]] and [[Pacific Railroad Act]]<nowiki/>s. Most of this land went to large owners and speculators instead of individual families.<ref name=":0" /><sup>:140–1</sup> | ||

=== West === | === West === | ||

| Line 15: | Line 23: | ||

== Progressive role == | == Progressive role == | ||

The Civil War began as a war against separatism, and Lincoln did not initially want to abolish slavery. Later, when slaves and | The Civil War began as a war against separatism, and Lincoln did not initially want to abolish slavery. Later, when slaves and freedmen entered the Union army, they turned the war into a [[revolution]] against slavery.<ref name=":122">{{Citation|author=[[Domenico Losurdo]]|year=2011|title=Liberalism: A Counter-History|chapter=Crisis of the English and American Models|page=166|publisher=Verso|isbn=9781844676934|lg=https://libgen.rs/book/index.php?md5=5BB3406BC2E64972831A1C00D5D4BFE4|pdf=https://cloudflare-ipfs.com/ipfs/bafykbzacebhsj2yxuoudkhkjp6lzgr5jvgyhu76zxe4gw3d65gpg32a6nded4?filename=Domenico%20Losurdo%2C%20Gregory%20Elliott%20-%20Liberalism_%20A%20Counter-History-Verso%20%282011%29.pdf}}</ref> After many enslaved people had already escaped to the North, Lincoln issued the [[Emancipation Proclamation]] in 1863 and allowed them to serve in the Union army.<ref name=":0" /><sup>:135–6</sup> | ||

== Marx's and Engels's Relation to the War == | |||

[[Karl Marx]] and [[Friedrich Engels]] followed the events of the Statesian Civil War closely. Marx and Engels wrote about the war in articles in the [[New York Daily Tribune|New York Tribune]], [[Die Presse]], as well as numerous letters to each other and various contacts in the [[International Workingmen's Association|international communist community]] (like [[Joseph Weydemeyer]] and [[Ferdinand Lassalle]]). Political refugees of the failed [[Revolutions of 1848|1848 Revolutions]], many of them German, came to settle in the now-midwestern Great Lakes area. This emigre community maintained contact with Marx and Engels and formed a strong abolitionist base that contributed to the rise of the newly founded [[Republican Party (United States)|Republican Party]].<ref name=":1" /> | |||

Marx, Engels, and the "48er" community immediately grasped the centrality of abolition to the successful prosecution of the North's war effort. Marx wrote to his uncle Lion Philips in May 1861, "in the early part of the struggle, the scales will be weighted in favor of the South, where the class of propertyless adventurers provides an inexhaustible source of marital militia. In the long run, of course, the North will be victorious since, if the need arises, it has a last card up its sleeve in the shape of a slave revolution." <ref name=":1">{{Citation|author=Friedrich Engels, Karl Marx, Andrew Zimmerman|year=2016|title=The Civil War in the United States|page=xvii-xx, 129-131, 167|city=New York City|publisher=International Publishers}}</ref> | |||

Marx elaborated a vigorous political-economic analysis of the causes and implications of the war. He argued furiously against British newspapers who tried to minimize the centrality of slavery and abolition in the prosecution of the war effort. Papers like ''[[The Economist]]'' and ''The Examiner,'' whose interests were bound up with industrialists dependent on cheap cotton from the slave states, tried to spin the conflict as one merely of "states' rights," that the North was the "aggressor," that the North was prosecuting the war in order to extend the protectionist [[Morrill Tariffs]], and to dismiss the idea that the North was on a road to abolishing slavery. Marx argued that the election of Lincoln and the platform of cutting off slavery's existential need to expand westward brought on the initial aggression from the South. He critiqued the southern slave oligarchy as an anti-democratic force that seized power against the general wishes of southern society (most of whom did not own slaves, or were enslaved people themselves).<ref>{{Web citation|author=Karl Marx|newspaper=New York Daily Tribune|title=The American Question in England|date=1861-10-11|url=https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1861/10/11.htm|retrieved=2024-07-20|quote=“In the first place says The Economist, “the assumption that the quarrel between the North and South is a quarrel between Negro freedom on the one side and Negro Slavery on the other, is as impudent as it is untrue. “The North,” says The Saturday Review, “does not proclaim abolition, and never pretended to fight for Anti-Slavery. The North has not hoisted for its oriflamme the sacred symbol of justice to the Negro; its cri de guerre is not unconditional abolition.” “If,” says The Examiner, “we have been deceived about the real significance of the sublime movement, who but the Federalists themselves have to answer for the deception?" [...] | |||

The limitation of Slavery to its constitutional area, as proclaimed by the Republicans, was the distinct ground upon which the menace of Secession was first uttered in the House of Representatives on December 19, 1859. Mr. Singleton (Mississippi) having asked Mr. Curtis (Iowa), “if the Republican party would never let the South have another foot of slave territory while it remained in the Union,” and Mr. Curtis having responded in the affirmative, Mr. Singleton said this would dissolve the Union. His advice to Mississippi was the sooner it got out of the Union the better — “gentlemen should recollect that [ ... ] Jefferson Davis led our forces in Mexico, and [...] still he lives, perhaps to lead the Southern army.” Quite apart from the economical law which makes the diffusion of Slavery a vital condition for its maintenance within its constitutional areas, the leaders of the South had never deceived themselves as to its necessity for keeping up their political sway over the United States. John Calhoun, in the defense of his propositions to the Senate, stated distinctly on Feb. 19, 1847, “that the Senate was the only balance of power left to the South in the Government,” and that the creation of new Slave States had become necessary “for the retention of the equipoise of power in the Senate.” Moreover, the Oligarchy of the 300,000 slave-owners could not even maintain their sway at home save by constantly throwing out to their white plebeians the bait of prospective conquests within and without the frontiers of the United States. If, then, according to the oracles of the English press, the North had arrived at the fixed resolution of circumscribing Slavery within its present limits, and of thus extinguishing it in a constitutional way, was this not sufficient to enlist the sympathies of Anti-Slavery England?}}</ref> These arguments exposed the mainstream English press as simultaneously trying to appeal to the abolitionist sensibilities of the English working class to criticize the North, while obscuring the class interests of the English owning class in assisting the South in the war effort (an interest further exposed and repudiated in the English press's and public's reactions to the [[Trent Affair]]).<ref>{{Web citation|author=Karl Marx|newspaper=New York Daily Tribune|title=English Public Opinion|date=1862-01-11|url=https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1862/02/01.htm|retrieved=2024-07-20|quote=The news of the pacific solution of the Trent conflict was, by the bulk of the English people, saluted with an exultation proving unmistakably the unpopularity of the apprehended war and the dread of its consequences. It ought never to be forgotten in the United States that at least the working classes of England, from the commencement to the termination of the difficulty, have never forsaken them. To them it was due that, despite the poisonous stimulants daily administered by a venal and reckless press, not one single public war meeting could be held in the United Kingdom during all the period that peace trembled in the balance. The only war meeting convened on the arrival of the La Plata, in the cotton salesroom of the Liverpool Stock Exchange, was a corner meeting where the cotton jobbers had it all to themselves. Even at Manchester, the temper of the working classes was so well understood that an insulated attempt at the convocation of a war meeting was almost as soon abandoned as thought of.}}</ref> | |||

While Marx and Engels supported the North's efforts against the slave oligarchy in the South, they often expressed disappointment at the lack of commitment to fully prosecute the war along abolitionist lines. Abraham Lincoln, for the first few years of the war, held off on emancipation and even dismissed [[John C. Fremont]] as Commander-in-Chief of the Union Army. Fremont was dismissed as a consequence of his radical emancipation orders in the western theater of the war, as well as due to political maneuverings of rivals within the [[Republican Party (United States)|Republican]] party. Until the end of 1862, Lincoln took a conciliatory attitude towards slave owners in border states like Kentucky, Maryland, and Delaware, who had chosen not to secede from the Union along with the other slave states in early 1861.<ref>{{Web citation|author=Karl Marx|newspaper=Die Presse|title=The Dismissal of Fremont|date=1861-11-19|url=https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1861/11/26.htm|retrieved=2024-07-20|quote=Frémont's dismissal from the post of Commander-in-Chief in Missouri forms a turning point in the history of the development of the American Civil War. Fremont has two great sins to expiate. He was the first candidate of the Republican Party for the presidential office (1856), and he is the first general of the North to have threatened the slaveholders with emancipation of slaves (August 30, 1861). He remains, therefore, a rival of candidates for the presidency in the future and an obstacle to the makers of compromises in the present. [...] | |||

For Seward, therefore, Frémont was the dangerous rival who had to be ruined; an undertaking that appeared so much the easier since Lincoln, in accordance with his legal tradition, has an aversion for all genius, anxiously clings to the letter of the Constitution and fights shy of every step that could mislead the "loyal" slaveholders of the border states.}}</ref><ref>{{Web citation|author=Karl Marx|newspaper=Die Press|title=The Crisis Over the Slavery Issue|date=1861-12-10|url=http://hiaw.org/defcon6/works/1861/12/14.html|retrieved=2024-07-20|quote=The United States has evidently entered a critical stage with regard to the slavery question, the question underlying the whole Civil War. General Fremont has been dismissed for declaring the slaves of rebels free. A directive to General Sherman, the commander of the expedition to South Carolina, was a little later published by the Washington Government, which goes further than Fremont, for it decrees that fugitive slaves even of loyal slave-owners should be welcomed and employed as workers and paid a wage, and under certain circumstances armed, and consoles the "loyal" owners with the prospect of receiving compensation later. Colonel Cochrane has gone even further than Fremont, he demands the arming of all slaves as a military measure. The Secretary of War Cameron publicly approves of Cochrane's "views". The Secretary of the Interior, on behalf of the government, then repudiates the Secretary of War. [...] | |||

The slavery question is being solved in practice in the border slave states even now, especially in Missouri and to a lesser extent in Kentucky, etc. A large-scale dispersal of slaves is taking place. For instance 50,000 slaves have disappeared from Missouri, some of them have run away, others have been transported by the slave-owners to the more distant southern states.}}</ref> While the prosecution of the war along "constitutional" rather than "revolutionary" lines elongated the war and gave way to numerous disasters for the North, this strategy eventually gave way to a more radical, abolitionist direction as the needs of the war came to dictate. Lincoln dismissed the incompetent [[George B. McClellan|General McClellan]] in November 1862 and announced the [[Emancipation Proclamation]] to be effective on January 1, 1863. Most important to this proclamation were the calls for recruiting "black regiments" of freedmen. 180,000 black men joined the Union Army during and after 1863, and crucially, "the very existence of organized units of armed black men, including many former slaves, challenged at the most fundamental level the institution of racial slavery in the South."<ref name=":1" /> | |||

Marx came to view Lincoln much more positively after 1863, even characterizing him as something of a reluctant revolutionary in an article for ''Die Presse'', October 1862.<ref>{{Web citation|author=Karl Marx|newspaper=Die Presse|title=Comments on the North American Events|date=1862-10-12|url=http://hiaw.org/defcon6/works/1862/10/12.html|retrieved=2024-07-20|quote=Lincoln’s proclamation is even more important than the Maryland campaign. Lincoln is a sui generis figure in the annals of history. fie has no initiative, no idealistic impetus, cothurnus, no historical trappings. He gives his most important actions always the most commonplace form. Other people claim to be “fighting for an idea”, when it is for them a matter of square feet of land. Lincoln, even when he is motivated by, an idea, talks about “square feet”. He sings the bravura aria of his part hesitatively, reluctantly and unwillingly, as though apologising for being compelled by circumstances “to act the lion”. The most redoubtable decrees — which will always remain remarkable historical documents-flung by him at the enemy all look like, and are intended to look like, routine summonses sent by a lawyer to the lawyer of the opposing party, legal chicaneries, involved, hidebound actiones juris. His latest proclamation, which is drafted in the same style, the manifesto abolishing slavery, is the most important document in American history since the establishment of the Union, tantamount to the tearing tip of the old American Constitution. | |||

Nothing is simpler than to show that Lincoln’s principal political actions contain much that is aesthetically. repulsive, logically inadequate, farcical in form and politically, contradictory, as is done by, the English Pindars of slavery, The Times, The Saturday Review and tutti quanti. But Lincoln’s place in the history of the United States and of mankind will, nevertheless, be next to that of Washington! Nowadays, when the insignificant struts about melodramatically on this side of the Atlantic, is it of no significance at all that the significant is clothed in everyday dress in the new world? | |||

Lincoln is not the product of a popular revolution. This plebeian, who worked his way tip from stone-breaker to Senator in Illinois, without intellectual brilliance, without a particularly outstanding character, without exceptional importance-an average person of good will, was placed at the top by the interplay of the forces of universal suffrage unaware of the great issues at stake. The new world has never achieved a greater triumph than by this demonstration that, given its political and social organisation, ordinary people of good will can accomplish feats which only heroes could accomplish in the old world!}}</ref> Marx's growing admiration for this "son of the working class" culminated in his drafting his famous congratulation letter to Lincoln on the occasion of his successful reelection bid in 1864, on behalf of the International Workingmen's Association.<ref>{{Web citation|author=Karl Marx|newspaper=marxists.org|title=Address of the International Working Men's Association to Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States of America|date=1864-11-22|url=https://www.marxists.org/history/international/iwma/documents/1864/lincoln-letter.htm|retrieved=2024-07-20|quote=We congratulate the American people upon your re-election by a large majority. If resistance to the Slave Power was the reserved watchword of your first election, the triumphant war cry of your re-election is Death to Slavery. | |||

From the commencement of the titanic American strife the workingmen of Europe felt instinctively that the star-spangled banner carried the destiny of their class. The contest for the territories which opened the dire epopee, was it not to decide whether the virgin soil of immense tracts should be wedded to the labor of the emigrant or prostituted by the tramp of the slave driver? [...] | |||

the working classes of Europe understood at once, even before the fanatic partisanship of the upper classes for the Confederate gentry had given its dismal warning, that the slaveholders' rebellion was to sound the tocsin for a general holy crusade of property against labor, and that for the men of labor, with their hopes for the future, even their past conquests were at stake in that tremendous conflict on the other side of the Atlantic. Everywhere they bore therefore patiently the hardships imposed upon them by the cotton crisis, opposed enthusiastically the proslavery intervention of their betters — and, from most parts of Europe, contributed their quota of blood to the good cause. | |||

While the workingmen, the true political powers of the North, allowed slavery to defile their own republic, while before the Negro, mastered and sold without his concurrence, they boasted it the highest prerogative of the white-skinned laborer to sell himself and choose his own master, they were unable to attain the true freedom of labor, or to support their European brethren in their struggle for emancipation; but this barrier to progress has been swept off by the red sea of civil war. | |||

The workingmen of Europe feel sure that, as the American War of Independence initiated a new era of ascendancy for the middle class, so the American Antislavery War will do for the working classes. They consider it an earnest of the epoch to come that it fell to the lot of Abraham Lincoln, the single-minded son of the working class, to lead his country through the matchless struggle for the rescue of an enchained race and the reconstruction of a social world.}}</ref> This optimism around "proletarian power" in the US presidency came to disappointment after Lincoln's assassination, when Andrew Johnson (another "son of the working class") proved more conciliatory with the formerly vanquished slaveholder oligarchy than to the freedmen. As Engels wrote to Marx in July 1865, "Mr. Johnson's policy is less and less to my liking [...] he is relinquishing all his power vis-a-vis the old lords in the South. If this should continue, all the old seccessionist scoundrels will be in Congress in Washington in 6 months time. Without coloured suffrage nothing can be done, and Johnson is leaving it up to the defeated, the ex-slaveowners, to decide on that. It is absurd."<ref name=":1" /> | |||

Karl Marx's observations of the USian Civil War had dramatic impact on his thought and political theory. The war coincided with the development of the First International and with Marx's writing of ''[[Capital, vol. I (1867)|Das Kapital.]]'' The progression of Statesian slavery unto abolition informed Marx's own thoughts on proletarian revolution. The bourgeois class in every country was increasingly identified as slaveholders, and "free labor" cast as a veiled form of slavery. Marx came to see the liberation of all the world's most wretchedly enslaved to be ''primary'' in advancing class struggle.<ref>{{Citation|author=Karl Marx|year=1867|title=Capital: A Critique of Political Economy|title-url=https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/download/pdf/Capital-Volume-I.pdf|chapter=Chapter 10: The Working Day|section=Section 7: The Struggle for a Normal Working Day. Reaction of the English Factory Acts on Other Countries|page=195|quote=In the United States of North America, every independent movement of the workers was paralysed so long as slavery disfigured a part of the Republic. Labour cannot emancipate itself in the white skin where in the black it is branded. But out of the death of slavery a new life at once arose. The first fruit of the Civil War was the eight hours’ agitation, that ran with the seven-leagued boots of the locomotive from the Atlantic to the Pacific, from New England to California. | |||

The General Congress of labour at Baltimore (August 16th, 1866) declared: | |||

“The first and great necessity of the present, to free the labour of this country from | |||

capitalistic slavery, is the passing of a law by which eight hours shall be the | |||

normal working day in all States of the American Union. We are resolved to put | |||

forth all our strength until this glorious result is attained.”|pdf=https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/download/pdf/Capital-Volume-I.pdf|city=Moscow|publisher=Progress Publishers|volume=1}}</ref><ref>{{Web citation|author=Karl Marx|newspaper=marxists.org|title=Marx to Sigfrid Meyer and August Vogt | |||

In New York|date=1870-04-09|url=https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1870/letters/70_04_09.htm|retrieved=2024-07-20|quote=Ireland is the bulwark of the English landed aristocracy. The exploitation of that country is not only one of the main sources of their material wealth; it is their greatest moral strength. They, in fact, represent the domination over Ireland. Ireland is therefore the cardinal means by which the English aristocracy maintain their domination in England itself. | |||

If, on the other hand, the English army and police were to be withdrawn from Ireland tomorrow, you would at once have an agrarian revolution in Ireland. But the downfall of the English aristocracy in Ireland implies and has as a necessary consequence its downfall in England. And this would provide the preliminary condition for the proletarian revolution in England. The destruction of the English landed aristocracy in Ireland is an infinitely easier operation than in England herself, because in Ireland the land question has been up to now the exclusive form of the social question because it is a question of existence, of life and death, for the immense majority of the Irish people, and because it is at the same time inseparable from the national question. Quite apart from the fact that the Irish character is more passionate and revolutionary than that of the English. [...] | |||

But the English bourgeoisie has also much more important interests in the present economy of Ireland. Owing to the constantly increasing concentration of leaseholds, Ireland constantly sends her own surplus to the English labour market, and thus forces down wages and lowers the material and moral position of the English working class. | |||

And most important of all! Every industrial and commercial centre in England now possesses a working class divided into two hostile camps, English proletarians and Irish proletarians. The ordinary English worker hates the Irish worker as a competitor who lowers his standard of life. In relation to the Irish worker he regards himself as a member of the ruling nation and consequently he becomes a tool of the English aristocrats and capitalists against Ireland, thus strengthening their domination over himself. He cherishes religious, social, and national prejudices against the Irish worker. His attitude towards him is much the same as that of the “poor whites” to the Negroes in the former slave states of the U.S.A.. The Irishman pays him back with interest in his own money. He sees in the English worker both the accomplice and the stupid tool of the English rulers in Ireland. | |||

This antagonism is artificially kept alive and intensified by the press, the pulpit, the comic papers, in short, by all the means at the disposal of the ruling classes. This antagonism is the secret of the impotence of the English working class, despite its organisation. It is the secret by which the capitalist class maintains its power. And the latter is quite aware of this. | |||

But the evil does not stop here. It continues across the ocean. The antagonism between Englishmen and Irishmen is the hidden basis of the conflict between the United States and England. It makes any honest and serious co-operation between the working classes of the two countries impossible. It enables the governments of both countries, whenever they think fit, to break the edge off the social conflict by their mutual bullying, and, in case of need, by war between the two countries. | |||

England, the metropolis of capital, the power which has up to now ruled the world market, is at present the most important country for the workers’ revolution, and moreover the only country in which the material conditions for this revolution have reached a certain degree of maturity. It is consequently the most important object of the International Working Men’s Association to hasten the social revolution in England. The sole means of hastening it is to make Ireland independent. Hence it is the task of the International everywhere to put the conflict between England and Ireland in the foreground, and everywhere to side openly with Ireland. It is the special task of the Central Council in London to make the English workers realise that for them the national emancipation of Ireland is not a question of abstract justice or humanitarian sentiment but the first condition of their own social emancipation.}}</ref><ref>{{Citation|author=Karl Marx|year=1871|title=The Civil War in France|title-url=https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/download/pdf/civil_war_france.pdf|page=12, 17, 36|quote=The English workmen call also upon their government to oppose by all its power the dismemberment of France, which a part of the English press is shameless enough to howl for. It is the same press that for 20 years deified Louis Bonaparte as the providence of Europe, that frantically cheered on the slaveholders’ rebellion. Now, as then, it drudges for the slaveholder. [...] | |||

It was only by the violent overthrow of the republic that the appropriators of wealth could hope to shift onto the shoulders of its producers the cost of a war which they, the appropriators, had themselves originated. Thus, the immense ruin of France spurred on these patriotic representatives of land and capital, under the very eyes and patronage of the invader, to graft upon the foreign war a civil war – a slaveholders’ rebellion. [...] | |||

To be burned down has always been the inevitable fate of all buildings situated in the front of battle of all the regular armies of the world. | |||

But in the war of the enslaved against their enslavers, the only justifiable war in history, this is by no means to hold good! The Commune used fire strictly as a means of defence.}}</ref> | |||

== References == | == References == | ||

<references /> | <references /> | ||

[[Category:History of the USA]] | [[Category:History of the USA]] | ||

[[Category:Slavery]] | [[Category:Slavery]] | ||

[[Category:Civil wars]] | |||

Latest revision as of 05:37, 4 August 2024

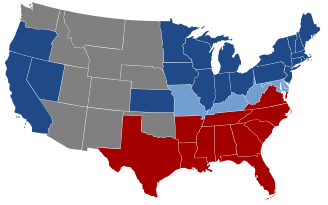

The Statesian Civil War was a civil war between the Statesian government (the Union) and the reactionary secessionist Confederate States of America (CSA) from 1861 to 1865. When the war began, 286 out of over 1,000 Statesian officers joined the Confederate Army.[1]:133

Background[edit | edit source]

Conflict between North and South over slavery began almost immediately after the Louisiana Purchase in 1803. The North officially abolished slavery in 1804, though using gradual emancipation laws that kept young Africans enslaved as late as the 1850s.[2] The industrializing North had little use for slavery, which was unprofitable for manufacturing. Unending streams of European immigrants to the North (in large part sourced by enclosure acts like those in Scotland in the early 1800s)[3] provided a huge reserve army of labor cheaper than what it would cost to buy, care for, guard, and educate enslaved people.

Even agricultural regions in the North were ill-suited to slavery, as wheat crops were seasonal and enslaved people would need vital needs provided year round. In the North, slavery wasn't abolished on a moral level, rather it was simply less economical than "free" labor from a reserve army of labor. This meant that the economic bases of the political estates in the North and South began to considerably diverge. The conflict between these political estates is characterized by the problem of whether slavery would expand to the new territories westward.

As territories began to become states, these political estates maintained a balance with the Missouri Compromise in 1820. This legislation ruled that slavery would not spread north of the 36º 30' latitude line for the new territories and that an equal number of free and slave states would enter the union, guaranteeing an equal number of senators for the northern and southern estates.

This political balance was once again disturbed by the acquisition of new lands westward, this time annexed from Mexico as a result of the Mexican-Statesian War. The new western land demanded that the question over slavery should be settled in the Kansas and Nebraska territories in preparation for the building of railroads. The political conflict resulted in the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, with its infamous "popular sovereignty" provision that directly contradicted the previous Missouri Compromise. The white men living in a territory would now themselves vote on becoming slave or free states. This resulted in the Bleeding Kansas border war, with pro-slavery "border ruffians" and anti-slavery forces flooding into the Kansas and Nebraska territories to sway the vote.[4] The guerrilla warfare between these forces, culminating in John Brown's attempt at slave revolution in Harper's Ferry in 1859, soon exploded into full-blown civil war.

In early 1861, several southern states of the USA seceded to form the Confederate States of America. Abraham Lincoln succeeded James Buchanan as President of the United States in March. The CSA seized the army base at Fort Sumter, South Carolina in April 1861, beginning the war.[1]:133

Indigenous involvement[edit | edit source]

Most of the Confederate officers had fought against indigenous nations in settler colonial wars.[1]:133 The Union also oppressed indigenous peoples and took almost 500 million acres of their land with the Homestead and Pacific Railroad Acts. Most of this land went to large owners and speculators instead of individual families.[1]:140–1

West[edit | edit source]

The Dakota people of Minnesota were starving by 1862 and began a revolt against the settlers. The Union crushed them and hanged 38 in the largest mass execution in U.S. history. John Chivington's volunteers killed 133 Cheyennes and Arapahos on the Sand Creek reservation. Colonel Patrick Connor massacred the Shoshone, Bannock, and Ute in Nevada and Utah. James Carleton fought against Cochise, the leader of the Apaches, in Arizona. He enlisted Kit Carson, who forced 8,000 Navajo people to march 300 miles to a concentration camp in the New Mexico desert. A quarter of them starved to death.[1]:136–9

Southeast[edit | edit source]

The southeastern natives (Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Muskogee, Seminole), who had been forced to move to Oklahoma during the 1830s, were split along class lines, with a tiny slave-owning elite supporting the Confederacy and the majority staying neutral. Stand Watie of the Cherokee became a general in the Confederate army, but many natives also fought against the CSA.[1]:134–5

Progressive role[edit | edit source]

The Civil War began as a war against separatism, and Lincoln did not initially want to abolish slavery. Later, when slaves and freedmen entered the Union army, they turned the war into a revolution against slavery.[5] After many enslaved people had already escaped to the North, Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863 and allowed them to serve in the Union army.[1]:135–6

Marx's and Engels's Relation to the War[edit | edit source]

Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels followed the events of the Statesian Civil War closely. Marx and Engels wrote about the war in articles in the New York Tribune, Die Presse, as well as numerous letters to each other and various contacts in the international communist community (like Joseph Weydemeyer and Ferdinand Lassalle). Political refugees of the failed 1848 Revolutions, many of them German, came to settle in the now-midwestern Great Lakes area. This emigre community maintained contact with Marx and Engels and formed a strong abolitionist base that contributed to the rise of the newly founded Republican Party.[6]

Marx, Engels, and the "48er" community immediately grasped the centrality of abolition to the successful prosecution of the North's war effort. Marx wrote to his uncle Lion Philips in May 1861, "in the early part of the struggle, the scales will be weighted in favor of the South, where the class of propertyless adventurers provides an inexhaustible source of marital militia. In the long run, of course, the North will be victorious since, if the need arises, it has a last card up its sleeve in the shape of a slave revolution." [6]

Marx elaborated a vigorous political-economic analysis of the causes and implications of the war. He argued furiously against British newspapers who tried to minimize the centrality of slavery and abolition in the prosecution of the war effort. Papers like The Economist and The Examiner, whose interests were bound up with industrialists dependent on cheap cotton from the slave states, tried to spin the conflict as one merely of "states' rights," that the North was the "aggressor," that the North was prosecuting the war in order to extend the protectionist Morrill Tariffs, and to dismiss the idea that the North was on a road to abolishing slavery. Marx argued that the election of Lincoln and the platform of cutting off slavery's existential need to expand westward brought on the initial aggression from the South. He critiqued the southern slave oligarchy as an anti-democratic force that seized power against the general wishes of southern society (most of whom did not own slaves, or were enslaved people themselves).[7] These arguments exposed the mainstream English press as simultaneously trying to appeal to the abolitionist sensibilities of the English working class to criticize the North, while obscuring the class interests of the English owning class in assisting the South in the war effort (an interest further exposed and repudiated in the English press's and public's reactions to the Trent Affair).[8]

While Marx and Engels supported the North's efforts against the slave oligarchy in the South, they often expressed disappointment at the lack of commitment to fully prosecute the war along abolitionist lines. Abraham Lincoln, for the first few years of the war, held off on emancipation and even dismissed John C. Fremont as Commander-in-Chief of the Union Army. Fremont was dismissed as a consequence of his radical emancipation orders in the western theater of the war, as well as due to political maneuverings of rivals within the Republican party. Until the end of 1862, Lincoln took a conciliatory attitude towards slave owners in border states like Kentucky, Maryland, and Delaware, who had chosen not to secede from the Union along with the other slave states in early 1861.[9][10] While the prosecution of the war along "constitutional" rather than "revolutionary" lines elongated the war and gave way to numerous disasters for the North, this strategy eventually gave way to a more radical, abolitionist direction as the needs of the war came to dictate. Lincoln dismissed the incompetent General McClellan in November 1862 and announced the Emancipation Proclamation to be effective on January 1, 1863. Most important to this proclamation were the calls for recruiting "black regiments" of freedmen. 180,000 black men joined the Union Army during and after 1863, and crucially, "the very existence of organized units of armed black men, including many former slaves, challenged at the most fundamental level the institution of racial slavery in the South."[6]

Marx came to view Lincoln much more positively after 1863, even characterizing him as something of a reluctant revolutionary in an article for Die Presse, October 1862.[11] Marx's growing admiration for this "son of the working class" culminated in his drafting his famous congratulation letter to Lincoln on the occasion of his successful reelection bid in 1864, on behalf of the International Workingmen's Association.[12] This optimism around "proletarian power" in the US presidency came to disappointment after Lincoln's assassination, when Andrew Johnson (another "son of the working class") proved more conciliatory with the formerly vanquished slaveholder oligarchy than to the freedmen. As Engels wrote to Marx in July 1865, "Mr. Johnson's policy is less and less to my liking [...] he is relinquishing all his power vis-a-vis the old lords in the South. If this should continue, all the old seccessionist scoundrels will be in Congress in Washington in 6 months time. Without coloured suffrage nothing can be done, and Johnson is leaving it up to the defeated, the ex-slaveowners, to decide on that. It is absurd."[6]

Karl Marx's observations of the USian Civil War had dramatic impact on his thought and political theory. The war coincided with the development of the First International and with Marx's writing of Das Kapital. The progression of Statesian slavery unto abolition informed Marx's own thoughts on proletarian revolution. The bourgeois class in every country was increasingly identified as slaveholders, and "free labor" cast as a veiled form of slavery. Marx came to see the liberation of all the world's most wretchedly enslaved to be primary in advancing class struggle.[13][14][15]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz (2014). An Indigenous Peoples' History of the United States: '"Indian Country"'. [PDF] Boston, Massachusetts: Beacon Press. ISBN 9780807000403

- ↑ “Pennsylvania passed its Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery in 1780. Yet, as late as 1850, the federal census recorded that there were still hundreds of young blacks in Pennsylvania, who would remain enslaved until their 28th birthdays.”

Nicholas Boston and Jennifer Hallam (2004). "Slavery and the Making of America" Thirteen PBS. Retrieved 2023-09-04. - ↑ “As for a large number of the human beings expelled to make room for the game of the Duke of Atholl, and the sheep of the Countess of Sutherland, where did they fly to, where did they find a home? In the United States of North America.”

Karl Marx (1853). The Duchess of Sutherland and Slavery. New York City: New York Daily Tribune. [MIA] - ↑ "The Kansas-Nebraska Act". United States Senate. Retrieved 2023-09-04.

- ↑ Domenico Losurdo (2011). Liberalism: A Counter-History: 'Crisis of the English and American Models' (p. 166). [PDF] Verso. ISBN 9781844676934 [LG]

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Friedrich Engels, Karl Marx, Andrew Zimmerman (2016). The Civil War in the United States (pp. xvii-xx, 129-131, 167). New York City: International Publishers.

- ↑ ““In the first place says The Economist, “the assumption that the quarrel between the North and South is a quarrel between Negro freedom on the one side and Negro Slavery on the other, is as impudent as it is untrue. “The North,” says The Saturday Review, “does not proclaim abolition, and never pretended to fight for Anti-Slavery. The North has not hoisted for its oriflamme the sacred symbol of justice to the Negro; its cri de guerre is not unconditional abolition.” “If,” says The Examiner, “we have been deceived about the real significance of the sublime movement, who but the Federalists themselves have to answer for the deception?" [...]

The limitation of Slavery to its constitutional area, as proclaimed by the Republicans, was the distinct ground upon which the menace of Secession was first uttered in the House of Representatives on December 19, 1859. Mr. Singleton (Mississippi) having asked Mr. Curtis (Iowa), “if the Republican party would never let the South have another foot of slave territory while it remained in the Union,” and Mr. Curtis having responded in the affirmative, Mr. Singleton said this would dissolve the Union. His advice to Mississippi was the sooner it got out of the Union the better — “gentlemen should recollect that [ ... ] Jefferson Davis led our forces in Mexico, and [...] still he lives, perhaps to lead the Southern army.” Quite apart from the economical law which makes the diffusion of Slavery a vital condition for its maintenance within its constitutional areas, the leaders of the South had never deceived themselves as to its necessity for keeping up their political sway over the United States. John Calhoun, in the defense of his propositions to the Senate, stated distinctly on Feb. 19, 1847, “that the Senate was the only balance of power left to the South in the Government,” and that the creation of new Slave States had become necessary “for the retention of the equipoise of power in the Senate.” Moreover, the Oligarchy of the 300,000 slave-owners could not even maintain their sway at home save by constantly throwing out to their white plebeians the bait of prospective conquests within and without the frontiers of the United States. If, then, according to the oracles of the English press, the North had arrived at the fixed resolution of circumscribing Slavery within its present limits, and of thus extinguishing it in a constitutional way, was this not sufficient to enlist the sympathies of Anti-Slavery England?”

Karl Marx (1861-10-11). "The American Question in England" New York Daily Tribune. Retrieved 2024-07-20. - ↑ “The news of the pacific solution of the Trent conflict was, by the bulk of the English people, saluted with an exultation proving unmistakably the unpopularity of the apprehended war and the dread of its consequences. It ought never to be forgotten in the United States that at least the working classes of England, from the commencement to the termination of the difficulty, have never forsaken them. To them it was due that, despite the poisonous stimulants daily administered by a venal and reckless press, not one single public war meeting could be held in the United Kingdom during all the period that peace trembled in the balance. The only war meeting convened on the arrival of the La Plata, in the cotton salesroom of the Liverpool Stock Exchange, was a corner meeting where the cotton jobbers had it all to themselves. Even at Manchester, the temper of the working classes was so well understood that an insulated attempt at the convocation of a war meeting was almost as soon abandoned as thought of.”

Karl Marx (1862-01-11). "English Public Opinion" New York Daily Tribune. Retrieved 2024-07-20. - ↑ “Frémont's dismissal from the post of Commander-in-Chief in Missouri forms a turning point in the history of the development of the American Civil War. Fremont has two great sins to expiate. He was the first candidate of the Republican Party for the presidential office (1856), and he is the first general of the North to have threatened the slaveholders with emancipation of slaves (August 30, 1861). He remains, therefore, a rival of candidates for the presidency in the future and an obstacle to the makers of compromises in the present. [...]

For Seward, therefore, Frémont was the dangerous rival who had to be ruined; an undertaking that appeared so much the easier since Lincoln, in accordance with his legal tradition, has an aversion for all genius, anxiously clings to the letter of the Constitution and fights shy of every step that could mislead the "loyal" slaveholders of the border states.”

Karl Marx (1861-11-19). "The Dismissal of Fremont" Die Presse. Retrieved 2024-07-20. - ↑ “The United States has evidently entered a critical stage with regard to the slavery question, the question underlying the whole Civil War. General Fremont has been dismissed for declaring the slaves of rebels free. A directive to General Sherman, the commander of the expedition to South Carolina, was a little later published by the Washington Government, which goes further than Fremont, for it decrees that fugitive slaves even of loyal slave-owners should be welcomed and employed as workers and paid a wage, and under certain circumstances armed, and consoles the "loyal" owners with the prospect of receiving compensation later. Colonel Cochrane has gone even further than Fremont, he demands the arming of all slaves as a military measure. The Secretary of War Cameron publicly approves of Cochrane's "views". The Secretary of the Interior, on behalf of the government, then repudiates the Secretary of War. [...]

The slavery question is being solved in practice in the border slave states even now, especially in Missouri and to a lesser extent in Kentucky, etc. A large-scale dispersal of slaves is taking place. For instance 50,000 slaves have disappeared from Missouri, some of them have run away, others have been transported by the slave-owners to the more distant southern states.”

Karl Marx (1861-12-10). "The Crisis Over the Slavery Issue" Die Press. Retrieved 2024-07-20. - ↑ “Lincoln’s proclamation is even more important than the Maryland campaign. Lincoln is a sui generis figure in the annals of history. fie has no initiative, no idealistic impetus, cothurnus, no historical trappings. He gives his most important actions always the most commonplace form. Other people claim to be “fighting for an idea”, when it is for them a matter of square feet of land. Lincoln, even when he is motivated by, an idea, talks about “square feet”. He sings the bravura aria of his part hesitatively, reluctantly and unwillingly, as though apologising for being compelled by circumstances “to act the lion”. The most redoubtable decrees — which will always remain remarkable historical documents-flung by him at the enemy all look like, and are intended to look like, routine summonses sent by a lawyer to the lawyer of the opposing party, legal chicaneries, involved, hidebound actiones juris. His latest proclamation, which is drafted in the same style, the manifesto abolishing slavery, is the most important document in American history since the establishment of the Union, tantamount to the tearing tip of the old American Constitution.

Nothing is simpler than to show that Lincoln’s principal political actions contain much that is aesthetically. repulsive, logically inadequate, farcical in form and politically, contradictory, as is done by, the English Pindars of slavery, The Times, The Saturday Review and tutti quanti. But Lincoln’s place in the history of the United States and of mankind will, nevertheless, be next to that of Washington! Nowadays, when the insignificant struts about melodramatically on this side of the Atlantic, is it of no significance at all that the significant is clothed in everyday dress in the new world?

Lincoln is not the product of a popular revolution. This plebeian, who worked his way tip from stone-breaker to Senator in Illinois, without intellectual brilliance, without a particularly outstanding character, without exceptional importance-an average person of good will, was placed at the top by the interplay of the forces of universal suffrage unaware of the great issues at stake. The new world has never achieved a greater triumph than by this demonstration that, given its political and social organisation, ordinary people of good will can accomplish feats which only heroes could accomplish in the old world!”

Karl Marx (1862-10-12). "Comments on the North American Events" Die Presse. Retrieved 2024-07-20. - ↑ “We congratulate the American people upon your re-election by a large majority. If resistance to the Slave Power was the reserved watchword of your first election, the triumphant war cry of your re-election is Death to Slavery.

From the commencement of the titanic American strife the workingmen of Europe felt instinctively that the star-spangled banner carried the destiny of their class. The contest for the territories which opened the dire epopee, was it not to decide whether the virgin soil of immense tracts should be wedded to the labor of the emigrant or prostituted by the tramp of the slave driver? [...]

the working classes of Europe understood at once, even before the fanatic partisanship of the upper classes for the Confederate gentry had given its dismal warning, that the slaveholders' rebellion was to sound the tocsin for a general holy crusade of property against labor, and that for the men of labor, with their hopes for the future, even their past conquests were at stake in that tremendous conflict on the other side of the Atlantic. Everywhere they bore therefore patiently the hardships imposed upon them by the cotton crisis, opposed enthusiastically the proslavery intervention of their betters — and, from most parts of Europe, contributed their quota of blood to the good cause.

While the workingmen, the true political powers of the North, allowed slavery to defile their own republic, while before the Negro, mastered and sold without his concurrence, they boasted it the highest prerogative of the white-skinned laborer to sell himself and choose his own master, they were unable to attain the true freedom of labor, or to support their European brethren in their struggle for emancipation; but this barrier to progress has been swept off by the red sea of civil war.

The workingmen of Europe feel sure that, as the American War of Independence initiated a new era of ascendancy for the middle class, so the American Antislavery War will do for the working classes. They consider it an earnest of the epoch to come that it fell to the lot of Abraham Lincoln, the single-minded son of the working class, to lead his country through the matchless struggle for the rescue of an enchained race and the reconstruction of a social world.”

Karl Marx (1864-11-22). "Address of the International Working Men's Association to Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States of America" marxists.org. Retrieved 2024-07-20. - ↑ “In the United States of North America, every independent movement of the workers was paralysed so long as slavery disfigured a part of the Republic. Labour cannot emancipate itself in the white skin where in the black it is branded. But out of the death of slavery a new life at once arose. The first fruit of the Civil War was the eight hours’ agitation, that ran with the seven-leagued boots of the locomotive from the Atlantic to the Pacific, from New England to California.

The General Congress of labour at Baltimore (August 16th, 1866) declared:

“The first and great necessity of the present, to free the labour of this country from

capitalistic slavery, is the passing of a law by which eight hours shall be the

normal working day in all States of the American Union. We are resolved to put

forth all our strength until this glorious result is attained.””

Karl Marx (1867). Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, vol. 1: 'Chapter 10: The Working Day; Section 7: The Struggle for a Normal Working Day. Reaction of the English Factory Acts on Other Countries'. [PDF] Moscow: Progress Publishers. - ↑ “Ireland is the bulwark of the English landed aristocracy. The exploitation of that country is not only one of the main sources of their material wealth; it is their greatest moral strength. They, in fact, represent the domination over Ireland. Ireland is therefore the cardinal means by which the English aristocracy maintain their domination in England itself.

If, on the other hand, the English army and police were to be withdrawn from Ireland tomorrow, you would at once have an agrarian revolution in Ireland. But the downfall of the English aristocracy in Ireland implies and has as a necessary consequence its downfall in England. And this would provide the preliminary condition for the proletarian revolution in England. The destruction of the English landed aristocracy in Ireland is an infinitely easier operation than in England herself, because in Ireland the land question has been up to now the exclusive form of the social question because it is a question of existence, of life and death, for the immense majority of the Irish people, and because it is at the same time inseparable from the national question. Quite apart from the fact that the Irish character is more passionate and revolutionary than that of the English. [...]

But the English bourgeoisie has also much more important interests in the present economy of Ireland. Owing to the constantly increasing concentration of leaseholds, Ireland constantly sends her own surplus to the English labour market, and thus forces down wages and lowers the material and moral position of the English working class.

And most important of all! Every industrial and commercial centre in England now possesses a working class divided into two hostile camps, English proletarians and Irish proletarians. The ordinary English worker hates the Irish worker as a competitor who lowers his standard of life. In relation to the Irish worker he regards himself as a member of the ruling nation and consequently he becomes a tool of the English aristocrats and capitalists against Ireland, thus strengthening their domination over himself. He cherishes religious, social, and national prejudices against the Irish worker. His attitude towards him is much the same as that of the “poor whites” to the Negroes in the former slave states of the U.S.A.. The Irishman pays him back with interest in his own money. He sees in the English worker both the accomplice and the stupid tool of the English rulers in Ireland.

This antagonism is artificially kept alive and intensified by the press, the pulpit, the comic papers, in short, by all the means at the disposal of the ruling classes. This antagonism is the secret of the impotence of the English working class, despite its organisation. It is the secret by which the capitalist class maintains its power. And the latter is quite aware of this.

But the evil does not stop here. It continues across the ocean. The antagonism between Englishmen and Irishmen is the hidden basis of the conflict between the United States and England. It makes any honest and serious co-operation between the working classes of the two countries impossible. It enables the governments of both countries, whenever they think fit, to break the edge off the social conflict by their mutual bullying, and, in case of need, by war between the two countries.

England, the metropolis of capital, the power which has up to now ruled the world market, is at present the most important country for the workers’ revolution, and moreover the only country in which the material conditions for this revolution have reached a certain degree of maturity. It is consequently the most important object of the International Working Men’s Association to hasten the social revolution in England. The sole means of hastening it is to make Ireland independent. Hence it is the task of the International everywhere to put the conflict between England and Ireland in the foreground, and everywhere to side openly with Ireland. It is the special task of the Central Council in London to make the English workers realise that for them the national emancipation of Ireland is not a question of abstract justice or humanitarian sentiment but the first condition of their own social emancipation.”

Karl Marx (1870-04-09). [https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1870/letters/70_04_09.htm "Marx to Sigfrid Meyer and August VogtIn New York"] marxists.org. Retrieved 2024-07-20.

- ↑ “The English workmen call also upon their government to oppose by all its power the dismemberment of France, which a part of the English press is shameless enough to howl for. It is the same press that for 20 years deified Louis Bonaparte as the providence of Europe, that frantically cheered on the slaveholders’ rebellion. Now, as then, it drudges for the slaveholder. [...]

It was only by the violent overthrow of the republic that the appropriators of wealth could hope to shift onto the shoulders of its producers the cost of a war which they, the appropriators, had themselves originated. Thus, the immense ruin of France spurred on these patriotic representatives of land and capital, under the very eyes and patronage of the invader, to graft upon the foreign war a civil war – a slaveholders’ rebellion. [...]

To be burned down has always been the inevitable fate of all buildings situated in the front of battle of all the regular armies of the world.

But in the war of the enslaved against their enslavers, the only justifiable war in history, this is by no means to hold good! The Commune used fire strictly as a means of defence.”

Karl Marx (1871). The Civil War in France (pp. 12, 17, 36).