Library:Vladimir Lenin/Materialism and empirio-criticism: Difference between revisions

More languages

More actions

Tag: Visual edit |

Tag: Visual edit |

||

| Line 433: | Line 433: | ||

==== What is matter? What is experience? ==== | ==== What is matter? What is experience? ==== | ||

The first of these questions is constantly being hurled by the idealists and agnostics, including the Machians, at the materialists; the second question by the materialists at the Machians. Let us try to make the point at issue clear. | |||

Avenarius says on the subject of matter: | |||

“Within the purified, ‘complete experience’ there is nothing ‘physical’—‘matter’ in the metaphysical absolute conception—for ‘matter’ according to this conception is only an abstraction; it would be the total of the counter-terms abstracted from every central term. Just as in the principal co-ordination, that is, ‘complete experience,’ a counter-term is inconceivable (''undenkbar'') without a central term, so ‘matter’ in the metaphysical absolute conception is a complete chimera (''Unding'')” (''Bemerkungen'' [''Notes''], S. 2, in the journal cited, § 119). | |||

In all this gibberish one thing is evident, namely, that Avenarius designates the physical or matter by the terms absolute and metaphysics, for, according to his theory of the principal co-ordination (or, in the new way, “complete expcrience"), the counter-term is inseparable from the central term, the environment from the ''self''; the ''non-self'' is inseparable from the ''self'' (as J. G. Fichte said). That this theory is disguised subjective idealism we have already shown, and the nature of Avenarius’ attacks on “matter” is quite obvious: the idealist denies physical being that is independent of the mind and therefore rejects the concept elaborated by philosophy for such being. That matter is “physical” (''i.e.''., that which is most familiar and immediately given to man, and the existence of which no one save an inmate of a lunatic asylum can doubt) is not denied by Avenarius; he only insists on the acceptance of “''his''” theory of the indissoluble connection between the environment and the ''self''. | |||

Mach expresses the same thought more simply, without philosophical flourishes: “What we call matter is a certain systematic combination of the ''elements'' (sensations)” (''Analysis of Sensations'', p. 265). Mach thinks that by this assertion he is effecting a “radical change” in the usual world outlook. In reality this is the old, old subjective idealism, the nakedness of which is concealed by the word “element.” | |||

And lastly, the English Machian, Pearson, a rabid antagonist of materialism, says: “Now there can be no scientific objection to our classifying certain more or less permanent groups of sense-impressions together and terming them matter,—to do so indeed leads us very near to John Stuart Mill’s definition of matter as a ‘permanent possibility of sensation,’—but this definition of matter then leads us entirely away from matter as the thing which moves” (''The Grammar of Science'', 2nd ed., 1900, p. 249). Here there is not even the fig-leaf of the “elements,” and the idealist openly stretches out a hand to the agnostic. | |||

As the reader sees, all these arguments of the founders of empirio-criticism entirely and exclusively revolve around the old epistemological question of the relation of thinking to being, of sensation to the physical. It required the extreme naïveté of the Russian Machians to discern anything here that is even remotely related to “recent science,” or “recent positivism.” All the philosophers mentioned by us, some frankly, others guardedly, replace the fundamental philosophical line of materialism (from being to thinking, from matter to sensation) by the reverse line of idealism. Their denial of matter is the old answer to epistemological problems, which consists in denying the existence of an external, objective source of our sensations, of an objective reality corresponding to our sensations. On the other hand, the recognition of the philosophical line denied by the idealists and agnostics is expressed in the definitions: matter is that which, acting upon our sense-organs, produces sensation; matter is the objective reality given to us in sensation, and so forth. | |||

Bogdanov, pretending to argue only against Beltov and cravenly ignoring Engels, is indignant at such definitions, which, don’t you see, “prove to be simple repetitions” (''Empirio-Monism'', Bk. III, p. xvi) of the “formula” (''of Engels'', our “Marxist” forgets to add) that for one trend in philosophy matter is primary and spirit secondary, while for the other trend the reverse is the case. All the Russian Machians exultantly echo Bogdanov’s “refutation"! But the slightest reflection could have shown these people that it is impossible, in the very nature of the case, to give any definition of these two ultimate concepts of epistemology save one that indicates which of them is taken as primary. What is meant by giving a “definition"? It means essentially to bring a given concept within a more comprehensive concept. For example, when I give the definition “an ass is an animal,” I am bringing the concept “ass” within a more comprehensive concept. The question then is, are there more comprehensive concepts, with which the theory of knowledge could operate, than those of being and thinking, matter and sensation, physical and mental? No. These are the ultimate concepts, the most comprehensive concepts which epistemology has in point of fact so far not surpassed (apart from changes in ''nomenclature'', which are ''always'' possible). One must be a charlatan or an utter blockhead to demand a “definition” of these two “series” of concepts of ultimate comprehensiveness which would not be a “mere repetition": one or the other must be taken as the primary. Take the three afore-mentioned arguments on matter. What do they all amount to? To this, that these philosophers proceed from the mental or the ''self'', to the physical, or environment, as from the central term to the counter-term—or from sensation to matter, or from sense-perception to matter. Could Avenarius, Mach and Pearson in fact have given any other “definition” of these fundamental concepts, save by pointing to the ''trend'' of their philosophical line? Could they have defined in any other way, in any specific way, what the ''self'' is, what sensation is, what sense-perception is? One has only to formulate the question clearly to realise what utter non-sense the Machians are talking when they demand that the materialists give a definition of matter which would not amount to a repetition of the proposition that matter, nature, being, the physical—is primary, and spirit, consciousness, sensation, the psychical—is secondary. | |||

One expression of the genius of Marx and Engels was that they despised pedantic playing with new words, erudite terms, and subtle “isms,” and said simply and plainly: there is a materialist line and an idealist line in philosophy, and between them there are various shades of agnosticism. The painful quest for a “new” point of view in philosophy betrays the same poverty of mind that is revealed in the painful effort to create a “new” theory of value, or a “new” theory of rent, and so forth. | |||

Of Avenarius, his disciple Carstanjen says that he once expressed himself in private conversation as follows: “I know neither the physical nor the mental, but only some third.” To the remark of one writer that the concept of this third was not given by Avenarius, Petzoldt replied: “We know why he could not advance such a concept. The third lacks a counter-concept (''Gegenbegriff''). . . . The question, what is the third? is illogically put” (''Einf''. ''i''.''d''. ''Ph''. ''d''. ''r''. ''E''., II, 329).[''Einführung in die Philosophie der reinen Erfahrung'' [''Introduction to the Philosophy of Pure Experience''], Vol. II, p. 329. –''Ed''] Petzoldt understands that an ultimate concept cannot be defined. But he does not understand that the resort to a “third” is a mere subterfuge, for every one of us knows what is physical and what is mental, but none of us knows at present what that “third” is. Avenarius was merely covering up his tracks by this subterfuge and ''actually'' was declaring that the ''self'' is the primary (central term) and nature (environment) the secondary (counter-term). | |||

Of course, even the antithesis of matter and mind has absolute significance only within the bounds of a very limited field—in this case exclusively within the bounds of the fundamental epistemological problem of what is to be regarded as primary and what as secondary. Beyond these bounds the relative character of this antithesis is indubitable. | |||

Let us now examine how the word “experience” is used in empirio-critical philosophy. The first paragraph of ''The Critique of Pure Experience'' expounds the following “assumption": “Any part of our environment stands in relation to human individuals in such a way that, the former having been given, the latter speak of their experience as follows: ‘this is experienced,’ ‘this is an experience’; or ‘it followed from experience,’ or ‘it depends upon experience.’” (Russ. trans., p. 1.) Thus experience is defined in terms of these same concepts: ''self'' and environment; while the “doctrine” of their “indissoluble” connection is for the time being tucked out of the way. Further: “The synthetic concept of pure experience"—namely, experience “as a predication for which, in all its components, only parts of the environment serve as a premise” (pp. 1 and 2). If we assume that the environment exists independently of “declarations” and “predications” of man, then it becomes possible to interpret experience in a materialist way! “The analytical concept of pure experience"—"namely, as a predication to which noth ing is admixed that would not be in its turn experience and which, therefore, in itself is nothing but experience” (p. 2). Experience is experience. And there are people who take this quasi-erudite rigmarole for true wisdom! | |||

It is essential to add that in the second volume of ''The Critique of Pure Experience'' Avenarius regards “experience” as a “special case” of the ''mental''; that he divides experience into ''sachhafte Werte'' (thing-values) and ''gedankenhafte Werte'' (thought-values); that “experience in the broad sense” includes the latter; that “complete experience” is identified with the principal co-ordination (''Bemerkungen''). In short, you pay your money and take your choice. “Experience” embraces both the materialist and the idealist line in philosophy and sanctifies the muddling of them. But while our Machians confidingly accept “pure experience” as pure coin of the realm, in philosophical literature the representatives of the various trends are alike in pointing to Avenarius’ abuse of this concept. “What pure experience is,” A. Riehl writes, “remains vague with Avenarius, and his explanation that ‘pure experience is experience to which nothing is admixed that is not in its turn experience’ obviously revolves in a circle” (''Systematische Philosophie'' [''Systematic Philosopby''], Leipzig, 1907, S. 102). Pure experience for Avenarius, writes Wundt, is at times any kind of fantasy, and at others, a predication with the character of “corporeality” (''Philosophische Studien'', XIII. Band, S. 92-93). Avenarius ''stretches'' the concept experience (S. 382). “On the precise definition of the terms experience and pure experience,” writes Cauwelaert, “depends the meaning of the whole of this philosophy. Avenarius does not give a precise definition” (''Revue néo-scolastique'', fevrier 1907, p. 61). “The vagueness of the term ‘experience’ stands him in good stead, and so in the end Avenarius falls back on the timeworn argument of subjective idealism” (under the pretence of combating it), says Norman Smith (''Mind'', Vol. XV, p. 29). | |||

“I openly declare that the inner sense, the soul of my philosophy consists in this that a human being possesses nothing save experience; a human being comes to everything to which he comes only through experience. . . .” A zealous philosopher of pure experience, is he not? The author of these words is the subjective idealist Fichte (''Sonnenklarer Bericht'', ''usw''., S. 12). We know from the history of philosophy that the interpretation of the concept experience divided the classical materialists from the idealists. Today professorial philosophy of all shades disguises its reactionary nature by declaiming on the subject of “experience.” All the immanentists fall back on experience. In the preface to the second edition of his ''Knowledge and Error'', Mach praises a book by Professor Wilhelm Jerusalem in which we read: “The acceptance of a divine original being is not contradictory to experience” (''Der kritische Idealismus und die reine Logik'' [''Critical Idealism and Pure Logic''], S. 222). | |||

One can only commiserate with people who believed Avenarius and Co. that the “obsolete” distinction between materialism and idealism can be surmounted by the word “experience.” When Valentinov and Yushkevich accuse Bogdanov, who departed somewhat from pure Machism, of abusing the word experience, these gentlemen are only betraying their ignorance. Bogdanov is “not guilty” in this case; he ''only'' slavishly borrowed the muddle of Mach and Avenarius. When Bogdanov says that “consciousness and immediate mental experience are identical concepts” (''Empirio-Monism'', Bk. II, p. 53) while matter is “not experience” but “the unknown which evokes everything known” (''Empirio-Monism'', Bk. III, p. xiii), he is interpreting experience ''idealistically''. And, of course, he is not the first<ref>In England Comrade Belfort Bax has been exercising himsclf in this way for a long time. A French reviewer of his book, ''The Roots of Reality'', rather bitingly remarked: experience is only another word for consciousness"; then come forth as an open idealist! (''Revue de philosophie'',<sup>[2]</sup> 1907, No. 10, p. 399). —''Lenin''</ref> nor the last to build petty idealist systems on the word experience. When he replies to the reactionary philosophers by declaring that attempts to transcend the boundaries of experience lead in fact “only to empty abstractions and contradictory images, all the elements of which have nevertheless been taken from experience” (Bk. I, p. 48), he is drawing a contrast between the empty abstractions of the human mind and that which exists outside of man and independently of his mind, in other words, he is interpreting experience as a materialist. | |||

Similarly, even Mach, although he makes idealism his starting point (bodies are complexes of sensations or “elements") frequently strays into a materialist interpretation of the word experience. “We must not philosophise out of ourselves (''nicht aus uns herausphilosophieren''), but must take from experience,” he says in the ''Mechanik'' (3rd Germ. ed., 1897, p. 14). Here a contrast is drawn between experience and philosophising out of ourselves, in other words, experience is regarded as something objective, something given to man from the outside; it is interpreted materialistically. Here is another example: “What we observe in nature is imprinted, although uncomprehended and unanalysed, upon our ideas, which, then, in their most general and strongest (''stärksten'') features imitate (''nachahmen'') the processes of nature. In these experiences we possess a treasure-store (''Schatz'') which is ever to hand. . .” (''op''. ''cit''., p. 27). Here nature is taken as primary and sensation and experience as products. Had Mach consistently adhered to this point of view in the fundamental questions of epistemology, he would have spared humanity many foolish idealist “complexes.” A third example: “The close connection of thought and experience creates modern natural science. Experience gives rise to a thought. The latter is further elaborated and is again compared with experience” (''Erkenntnis und Irrtum'', S. 200). Mach’s special “philosophy” is here thrown overboard, and the author instinctively accepts the customary standpoint of the scientists, who regard experience materialistically. | |||

To summarise: the word “experience,” on which the Machians build their systems, has long been serving as a shield for idealist systems, and is now serving Avenarius and Co. in eclectically passing to and fro between the idealist position and the materialist position. The various “definitions” of this concept are only expressions of those two fundamental lines in philosophy which were so strikingly revealed by Engels. | |||

==== Plekhanov’s error concerning the concept “experience” ==== | ==== Plekhanov’s error concerning the concept “experience” ==== | ||

On pages x-xi of his introduction to ''L. Feuerbach'' (1905 ed.) Plekhanov says: | |||

“One German writer has remarked that for empirio-criticism ''experience'' is only an object of investigation, and not a means of knowledge. If that is so, then the distinction between empirio-criticism and materialism loses all meaning, and discussion of the question whether or not empirio-criticism is destined to replace materialism is absolutely shallow and idle.” | |||

This is one complete muddle. | |||

Fr. Carstanjen, one of the most “orthodox” followers of Avenarius, says in his article on empirio-criticism (a reply to Wundt), that “for ''The Critique of Pure Experience'' experience is not a means of knowledge but only an object of investigation."<sup>[1]</sup> It follows that according to Plekhanov any distinction between the views of Fr. Carstanjen and materialism is meaningless! | |||

Fr. Carstanjen is almost literally quoting Avenarius, who in his ''Notes'' emphatically contrasts his conception of experience as that which is given us, that which we find (''das Vorgefundene''), with the conception of experience as a “means of knowledge” in “the sense of the prevailing theories of knowledge, which essentially are fully metaphysical” (''op''. ''cit''., p. 401). Petzoldt, following Avenarius, says the same thing in his ''Introduction to the Philosophy of Pure Experience'' (Bd. I, S. 170). Thus, according to Plekhanov, the distinction between the views of Carstanjen, Avenarius, Petzoldt and materialism is meaningless! Either Plekhanov has not read Carstanjen and Co. as thoroughly as he should, or he has taken his reference to “a German writer” at fifth hand. | |||

What then does this statement, uttered by some of the most prominent empirio-criticists and not understood by Plekhanov, mean? Carstanjen wishes to say that Avenarius in his ''The Critique of Pure Experience'' takes experience, ''i.e.''., all “human predications,” as the ''object'' of investigation. Avenarius does not investigate here, says Carstanjen (''op''. ''cit''., p. 50), whether these predications are real, or whether they relate, for example, to ghosts; he merely arranges, systematises, formally classifies all possible human predications, ''both idealist and materialist'' (p. 53), without going into the essence of the question. Carstanjen is absolutely right when he characterises ''this'' point of view as “scepticism par excellence” (p. 213). In this article, by the way, Carstanjen defends his beloved master from the ignominious (for a German professor) charge of materialism levelled against him by Wundt. Why are we materialists, pray?—such is the burden of Carstanjen’s objections—when we speak of “experience” we do not mean it in the ordinary current sense, which leads or might lead to materialism, but in the sense that we investigate everything that men “predicate” as experience. Carstanjen and Avenarius regard the view that experience is a means of knowledge as materialistic (that, perhaps, is the most common opinion, but nevertheless, untrue, as we have seen in the case of Fichte). Avenarius entrenches himself against the “prevailing” “metaphysics” which persists in regarding the brain as the organ of thought and which ignores the theories of introjection and co-ordination. By the given or the found (''das Vorgefundene''), Avenarius means the indissoluble connection between the ''self'' and the environment, which leads to a confused idealist interpretation of “experience.” | |||

Hence, both the materialist and the idealist, as well as the Humean and the Kantian lines in philosophy may unquestionably be concealed beneath the word “experience"; but neither the definition of experience as an object of investigation<ref>Plekhanov perhaps thought that Carstanjen had said, “an object of knowledge independent of knowledge,” and not an “object of investigation"? This would indeed be materialism. But neither Carstanjen, nor anybody else acquainted with empirio-criticism, said or could have said, any such thing. —''Lenin''</ref>, nor its definition as a means of knowledge is decisive in this respect. Carstanjen’s remarks against Wundt especially have no relation whatever to the question of the distinction between empirio-criticism and materialism. | |||

As a curiosity let us note that on this point Bogdanov and Valentinov, in their reply to Plekhanov, revealed no greater knowledge of the subject. Bogdanov declared: “It is not quite clear” (Bk. III, p. xi).—"It is the task of empirio-criticists to examine this formulation and to accept or reject the condition.” A very convenient position: I, forsooth, am not a Machian and am not therefore obliged to find out in what sense a certain Avenarius or Carstanjen speaks of experience! Bogdanov wants to make use of Machism (and of the Machian confusion regarding “experience"), but he does not want to be held responsible for it. | |||

The “pure” empirio-criticist Valentinov transcribed Plekhanov’s remark and publicly danced the cancan; he sneered at Plekhanov for not naming the author and for not explaining what the matter was all about (''op''. ''cit''., pp. 108-09). But at the same time this empirio-critical philosopher in his answer said ''not a single word'' on the substance of the matter, although acknowledging that he had read Plekhanov’s remark “three times or more” (and had apparently not under stood it). Oh, those Machians! | |||

==== Causality and necessity in nature ==== | ==== Causality and necessity in nature ==== | ||

The question of causality is particularly important in determining the philosophical line of any new “ism,” and we must therefore dwell on it in some detail. | |||

Let us begin with an exposition of the materialist theory of knowledge on this point. L. Feuerbach’s views are expounded with particular clarity in his reply to R. Haym already referred to. | |||

‘Nature and human reason,’ says Haym, ‘are for him (Feuerbach) completely divorced, and between them a gulf is formed which cannot be spanned from one side or the other.’ Haym grounds this reproach on § 48 of my ''Essence of Religion'' where it is said that ‘nature may be conceived only through nature itself, that its necessity is neither human nor logical, neither metaphysical nor mathematical, that nature alone is the being to which it is impossible to apply any human measure, although we compare and give names to its phenomena, in order to make them comprehensible to us, and in general apply human expressions and conceptions to them, as for example: order, purpose, law; and are obliged to do so because of the character of our language.’ What does this mean? Does it mean that there is no order in nature, so that, for example, autumn may be succeeded by summer, spring by winter, winter by autumn? That there is no purpose, so that, for example, there is no co-ordination between the lungs and the air, between light and the eye, between sound and the ear? That there is no law, so that, for example, the earth may move now in an ellipse, now in a circle, that it may revolve around the sun now in a year, now in a quarter of an hour? What nonsense! What then is meant by this passage? Nothing more than to distinguish between that which belongs to nature and that which be longs to man; it does not assert that there is actually nothing in nature corresponding to the words or ideas of order, purpose, law. All that it does is to deny the identity between thought and being; it denies that they exist in nature exactly as they do in the head or mind of man. Order, purpose, law are words used by man to translate the acts of nature into ''his own'' language in order that he may understand them. These words are not devoid of meaning or of objective content (''nicht sinn-, d. h. gegenstandslose Worte''); nevertheless, a distinction must be made between the original and the translation. Order, purpose, law in the human sense express something arbitrary. | |||

“From the contingency of order, purpose and law in nature, theism ''expressly'' infers their arbitrary origin; it infers the existence of a being distinct from nature which brings order, purpose, law into a nature that is in itself (''an sich'') chaotic (''dissolute'') and indifferent to all determination. The reason of the theists . . . is reason contradictory to nature, reason absolutely devoid of understanding of the essence of nature. The reason of the theists splits nature into two beings—one material, and the other formal or spiritual” (''Werke'', VII. Band, 1903, S. 518-20). | |||

Thus Feuerbach recognises objective law in nature and objective causality, which are reflected only with approximate fidelity by human ideas of order, law and so forth. With Feuerbach the recognition of objective law in nature is inseparably connected with the recognition of the objective reality of the external world, of objects, bodies, things, reflected by our mind. Feuerbach’s views are consistently materialistic. All other views, or rather, any other philosophical line on the question of causality, the denial of objective law, causality and necessity in nature, are justly regarded by Feuerbach as belonging to the fideist trend. For it is, indeed, clear that the subjectivist line on the question of causality, the deduction of the order and necessity of nature not from the external objective world, but from consciousness, reason, logic, and so forth, not only cuts human reason off from nature, not only opposes the former to the latter, but makes nature a ''part'' of reason, instead of regarding reason as a part of nature. The subjectivist line on the ques-tion of causality is philosophical idealism (varieties of which are the theories of causality of Hume and Kant), ''i.e.''., fideism, more or less weakened and diluted. The recognition of objective law in nature and the recognition that this law is reflected with approximate fidelity in the mind of man is materialism. | |||

As regards Engels, he had, if I am not mistaken, no occasion to contrast his materialist view with other trends on the particular question of causality. He had no need to do so, since he had definitely dissociated himself from all the agnostics on the more fundamental question of the objective reality of the external world in general. But to anyone who has read his philosophical works at all attentively it must be clear that Engels does not admit even the shadow of a doubt as to the existence of objective law, causality and necessity in nature. We shall confine ourselves to a few examples. In the first section of ''Anti-Dühring'' Engels says: “In order to understand these details [of the general picture of the world phenomena], we must detach them from their natural (''natürlich'') or historical connection and examine each one separately, its nature, special causes, effects, etc.” (pp. 5-6). That this natural connection, the connection between natural phenomena, exists objectively, is obvious. Engels particularly emphasises the dialectical view of cause and effect: “And we find, in like manner, that cause and effect are conceptions which only hold good in their application to individual cases, but as soon as we consider the individual cases in their general connection with the universe as a whole, they run into each other, and they become confounded when we contemplate that universal action and reaction in which causes and effects are eternally changing places, so that what is effect here and now will be cause there and then, and ''vice versa''” (p. 8). Hence, the human conception of cause and effect always somewhat simplifies the objective connection of the phenomena of nature, reflecting it only approximately, artificially isolating one or another aspect of a single world process. If we find that the laws of thought correspond with the laws of nature, says Engels, this becomes quite conceivable when we take into account that reason and consciousness are “products of the human brain and that man himself is a product of nature.” Of course, “the products of the human brain, being in the last analysis also products of nature, do not contradict the rest of nature’s interconnections (''Naturzusammenhang'') but are in correspondence with them” (p. 22).[5] There is no doubt that there exists a natural, objective interconnection between the phenomena of the world. Engels constantly speaks of the “laws of nature,” of the “necessities of nature” (''Naturnotwendigkeiten''), without considering it necessary to explain the generally known propositions of materialism. | |||

In ''Ludwig Feuerbach'' also we read that “the general laws of motion—both of the external world and of human thought—[are] two sets of laws which are identical in substance but differ in their expression in so far as the human mind can apply them consciously, while in nature and also up to now for the most part in human history, these laws assert themselves unconsciously in the form of external necessity in the midst of an endless series of seeming accidents” (p. 38). And Engels reproaches the old natural philosophy for having replaced “the real but as yet unknown interconnections” (of the phenomena of nature) by “ideal and imaginary ones” (p. 42).[6] Engels’ recognition of objective law, causality and necessity in nature is absolutely clear, as is his emphasis on the relative character of our, ''i.e''., man’s approximate reflections of this law in various concepts. | |||

Passing to Joseph Dietzgen, we must first note one of the innumerable distortions committed by our Machians. One of the authors of the ''Studies'' “''in” the Philosophy of Marxism'', Mr. Helfond, tells us: “The basic points of Dietzgen’s world outlook may be summarised in the following propositions: . . . (9) The causal dependence which we ascribe to things is in reality not contained in the things themselves” (p. 248). ''This is sheer nonsense''. Mr. Helfond, whose own views represent a veritable hash of materialism and agnosticism, ''has outrageously falsified'' J. Dietzgen. Of course, we can find plenty of confusion, inexactnesses and errors in Dietzgen, such as gladden the hearts of the Machians and oblige materialists to regard Dietzgen as a philosopher who is not entirely consistent. But to attribute to the materialist J. Dietzgen a direct denial of the materialist view of causality—only a Helfond, only the Russian Machians are capable of that. | |||

“Objective scientific knowledge,” says Dietzgen in his ''The Nature of the Workings of the Human Mind'' (German ed. 1903), “seeks for causes not by faith or speculation, but by experience and induction, not ''a priori'', but ''a posteriori''. Natural science looks for causes not outside or back of phenomena, but within or by means of them” (pp. 94-95). “Causes are the products of the faculty of thought. They are, however, not its pure products, but are produced by it in conjunction with sense material. This sense material gives the causes thus derived their objective existence. Just as we demand that a truth should be the truth of an objective phenomenon, so we demand that a cause should be real, that it should be the cause of some objective effect” (pp. 98-99). “The cause of the thing is its connection” (p. 100). | |||

It is clear from this that Mr. Helfond has made a statement which is ''directly contrary to fact''. The world outlook of materialism expounded by J. Dietzgen recognises that “the causal dependence” is ''contained'' “in the things themselves.” It was necessary for the Machian hash that Mr. Helfond should confuse the materialist line with the idealist line on the question of causality. | |||

Let us now proceed to the latter line. | |||

A clear statement of the starting point of Avenarius’ philosophy on this question is to be found in his first work, ''Philosophie als Denken der Welt gemäss dem Prinzip des kleinsten Kraftmasses''. In § 81 we read: “Just as we do not experience (''erfahren'') force as causing motion, so we do not experience the ''necessity'' for any motion. . . . All we experience (''erfahren'') is that the one follows the other.” This is the Humean standpoint in its purest form: sensation, experience tell us nothing of any necessity. A philosopher who asserts (on the principle of “the economy of thought") that only sensation exists could not have come to any other conclusion. “Since the idea of ''causality'',” we read further, “demands force and necessity or constraint as integral parts of the effect, so it falls together with the latter” (§ 82). “Necessity therefore expresses a particular degree of probability with which the effect is, or may be, expected” (§ 83, thesis). | |||

This is outspoken subjectivism on the question of causality. And if one is at all consistent one cannot come to any other conclusion unless one recognises objective reality as the source of our sensations. | |||

Let us turn to Mach. In a special chapter, “Causality and Explanation” (''Wärmelehre'', 2. Auflage, 1900, S. 432-39), we read: “The Humean criticism (of the conception of causality) nevertheless retains its validity.” Kant and Hume (Mach does not trouble to deal with other philosophers) solve the problem of causality differently. “We prefer” Hume’s solution. “Apart from ''logical'' necessity [Mach’s italics] no other necessity, for instance physical necessity, exists.” This is exactly the view which was so vigorously combated by Feuerbach. It never even occurs to Mach to deny his kinship with Hume. Only the Russian Machians could go so far as to assert that Hume’s agnosticism could be “combined” with Marx’s and Engels’ materialism. In Mach’s ''Mechanik'', we read: “In nature there is neither cause nor effect” (S. 474, 3. Auflage, 1897). “I have repeatedly demonstrated that all forms of the law of causality spring from subjective motives (''Trieben'') and that there is no necessity for nature to correspond with them” (p. 495). | |||

We must here note that our Russian Machians with amazing naïveté replace the question of the materialist or idealist trend of all arguments on the law of causality by the question of one or another formulation of this law. They believed the German empirio-critical professors that merely to say “functional correlation” was to make a discovery in “recent positivism” and to release one from the “fetishism” of expressions like “necessity,” “law,” and so forth. This of course is utterly absurd, and Wundt was fully justified in ridiculing such a ''change of words'' (in the article, quoted above, in ''Philosophische Studien'', S. 383, 388), which in fact changes nothing. Mach himself speaks of “all forms” of the law of causality and in his ''Knowledge and Error'' (2. Auflage, S. 278) makes the self-evident reservation that the concept function can express the “dependence of elements” more precisely only when the possibility is achieved of expressing the results of investigation in ''measurable'' quantities, which even in sciences like chemistry has only partly been achieved. Apparently, in the opinion of our Machians, who are so credulous as to professorial discoveries, Feuerbach (not to mention Engels) did not know that the concepts order, law, and so forth, can under certain conditions be expressed as a mathematically defined functional relation! | |||

The really important epistemological question that divides the philosophical trends is not the degree of precision attained by our descriptions of causal connections, or whether these descriptions can be expressed in exact mathematical formulas, but whether the source of our knowledge of these connections is objective natural law or properties of our mind, its innate faculty of apprehending certain ''a priori'' truths, and so forth. This is what so irrevocably divides the materialists Feuerbach, Marx and Engels from the agnostics (Humeans) Avenarius and Mach. | |||

In certain parts of his works, Mach, whom it would be a sin to accuse of consistency, frequently “forgets” his agreement with Hume and his own subjectivist theory of causality and argues “simply” as a natural scientist, ''i.e.''., from the instinctive materialist standpoint. For instance, in his ''Mechanik'', we read of “the uniformity which nature teaches us to find in its phenomena” (French ed., p. 182). But if we ''do find'' uniformity in the phenomena of nature, does this mean that uniformity exists objectively outside our mind? No. On the question of the uniformity of nature Mach also delivers himself thus: “The power that prompts us to complete in thought facts only partially observed is the power of association. It is greatly strengthened by repetition. It then appears to us to be a power which is independent of our will and of individual facts, a power which directs thoughts ''and'' [Mach’s italics] facts, which keeps both in mutual correspondence as a law governing both. That we consider ourselves capable of making predictions with the help of such a law only [!] proves that there is sufficient uniformity in our environment, but it does not prove the necessity of the success of our predictions” (''Wärmelehre'', S. 383). | |||

It follows that we may and ought to look for a necessity ''apart from'' the uniformity of our environment, ''i.e.''., of nature! Where to look for it is the secret of idealist philosophy which is afraid to recognise man’s perceptive faculty as a simple reflection of nature. In his last work, ''Knowledge and Error'' Mach even defines a law of nature as a “limitation of expectation” (2. Auflage, S. 450 ff.)! Solipsism claims its own. | |||

Let us examine the position of other writers of the same philosophical trend. The Englishman, Karl Pearson, expresses himself with characteristic precision (''The Grammar of Science'', 2nd ed.): “The laws of science are products of the human mind rather than factors of the external world” (p. 36). “Those, whether poets or materialists, who do homage to nature, as the sovereign of man, too often forget that the order and complexity they admire are at least as much a product of man’s perceptive and reasoning faculties as are their own memories and thoughts” (p. 185). “The comprehensive character of natural law is due to the ingenuity of the human mind” (''ibid''.). “''Man is the maker of natural law'',” it is stated in Chapter III, § 4. “There is more meaning in the statement that man gives laws to nature than in its converse that nature gives laws to man,” although the worthy professor is regretfully obliged to admit, the latter (materialist) view is “unfortunately far too common today” (p. 87). In the fourth chapter, which is devoted to the question of causality, Pearson formulates the following ''thesis'' (§ 11): “''The necessity lies in the world of conceptions and not in the world of perceptions''.” It should be noted that for Pearson perceptions or sense-impressions are the reality existing outside us. “In the uniformity with which sequences of perception are repeated (the routine of perceptions) there is also no inherent necessity, but it is a necessary condition for the existence of thinking beings that there should be a routine in the perceptions. The necessity thus lies in the nature of the thinking being and not in the perceptions themselves; thus it is conceivably a product of the perceptive faculty (p. 139) | |||

Our Machian, with whom Mach himself frequently expresses complete solidarity, thus arrives safely and soundly at pure Kantian idealism: it is man who dictates laws to nature and not nature that dictates laws to man! The important thing is not the repetition of Kant’s doctrine of apriorism—which does not define the idealist line in philosophy as such, but only a particular formulation of this line—but the fact that reason, mind, consciousness are here primary, and nature secondary. It is not reason that is a part of nature, one of its highest products, the reflection of its processes, but nature that is a part of reason, which thereby is stretched from the ordinary, simple human reason known to us all to a “stupendous,” as Dietzgen puts it, mysterious, divine reason. The Kantian-Machian formula, that “man gives laws to nature,” is a fideist formula. If our Machians stare wide-eyed on reading Engels’ statement that the fundamental characteristic of materialism is the acceptance of nature and not spirit as primary, it only shows how incapable they are of distinguishing the really important philosophical trends from the mock erudition and sage jargon of the professors. | |||

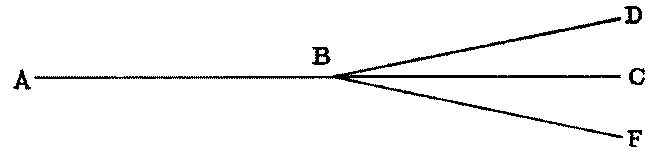

J. Petzoldt, who in his two-volume work analysed and developed Avenarius, may serve as an excellent example of reactionary Machian scholasticism. “Even to this day,” says he, “one hundred and fifty years after Hume, substantiality and causality paralyse the daring of the thinker” (''Introduction to the Philosophy of Pure Experience'', Bd. I, S. 31). It goes without saying that those who are most “daring” are the solipsists who discovered sensation without organic matter, thought without brain, nature without objective law! “And the last formulation of causality, which we have not yet mentioned, necessity, or ''necessity in nature'', contains something vague and mystical"—(the idea of “fetishism,” “anthropomorphism,” etc.) (pp. 32, 34). Oh, the poor mystics, Feuerbach, Marx and Engels! They have been talking all the time of necessity in nature, and have even been calling those who hold the Humean position theoretical reactionaries! Petzoldt rises above all “anthropomorphism.” He has discovered the great “''law of unique determination'',” which eliminates every obscurity, every trace of “fetishism,” etc., etc., etc. For example, the parallelogram of forces (p. 35). This cannot be “proven"; it must be accepted as a “fact of experience.” It cannot be conceded that a body under like impulses will move in different ways. “We cannot concede nature such indefiniteness and arbitrariness; we must demand from it definiteness and law” (p. 35). Well, well! We demand of nature obedience to law. The bourgeoisie demands reaction of its professors. “Our thought demands definiteness from nature, and nature always conforms to this demand; we shall even see that in a certain sense it is compelled to conform to it” (p. 36). Why, having received an impulse in the direction of the line AB, does a body move towards C and not towards D or F, etc.? | |||

[[File:Materialism-Empiriocriticism-img01.png|none|thumb]] | |||

“Why does nature not choose any of the countless other directions?” (p. 37). Because that would be “multiple determination,” and the great empirio-critical discovery of Joseph Petzoldt demands ''unique determination''. | |||

The “empirio-criticists” fill scores of pages with such unutterable trash! | |||

“. . . We have remarked more than once that our thesis does not derive its force from a sum of separate experiences, but that, on the contrary, we demand that nature should recognise its validity (''seine Geltung''). Indeed, even before it becomes a law it has already become for us a principle with which we approach reality, a postulate. It is valid, so to speak, ''a priori'', independently of all separate experiences. It would, indeed, be unbefitting for a philosophy of pure experience to preach ''a priori'' truths and thus relapse into the most sterile metaphysics. Its apriorism can only be a logical one, never a psychological, or metaphysical one” (p. 40). Of course, if we call apriorism logical, then the reactionary nature of the idea disappears and it becomes elevated to the level of “recent positivism"! | |||

There can be no unique determination of psychical phenomena, Petzoldt further teaches us; the role of imagination, the significance of great inventions, etc., here create exceptions, while the law of nature, or the law of spirit, tolerates “no exceptions” (p. 65). We have before us a pure metaphysician, who has not the slightest inkling of the relativity of the difference between the contingent and the necessary. | |||

I may, perhaps, be reminded—continues Petzoldt—of the motivation of historical events or of the development of character in poetry. “If we examine the matter carefully we shall find that there is no such unique determination. There is not a single historical event or a single drama in which we could not imagine the participants acting differently under similar psychical conditions. . .” (p. 73). “Unique determination is not only absent in the realm of the psychical, but we are also entitled to ''demand'' its absence from reality [Petzoldt’s italics]. Our doctrine is thus elevated to the rank of a ''postulate'', ''i.e.''., to the rank of a fact, which we regard as a necessary condition of a much earlier experience, as its ''logical a priori''” (Petzoldt’s italics, p. 76). | |||

And Petzoldt continues to operate with this “logical ''a priori''” in both volumes of his ''Introduction'', and in the booklet issued in 1906, ''The World Problem from the Positivist Standpoint''.<sup>[1]</sup> Here is a second instance of a noted empirio-criticist who has imperceptibly slipped into Kantianism and who serves up the most reactionary doctrines with a somewhat different sauce. And this is not fortuitous, for at the very foundations of Mach’s and Avenarius’ teachings on causality there lies an idealist falsehood, which no highflown talk of “positivism” can cover up. The distinction between the Humean and the Kantian theories of causality is only a secondary difference of opinion between agnostics who are basically at one, ''viz''., in their denial of objective law in nature, and who thus inevitably condemn themselves to idealist conclusions of one kind or another. A rather more “scrupulous” empirio-criticist than J. Petzoldt, Rudolf Willy, who is ashamed of his kinship with the immanentists, rejects, for example, Petzoldt’s whole theory of “unique determination” as leading to nothing but “logical formalism.” But does Willy improve his position by disavowing Petzoldt? Not in the least, for he disavows Kantian agnosticism solely for the sake of Humean agnosticism. “We have known from the time of Hume,” he writes, “that ‘necessity’ is a purely logical (not a ‘transcendental’) characteristic (''Merkmal''), or, as I would rather say and have already said, a purely verbal (''sprachlich'') characteristic” (R. Willy, ''Gegen die Schulweisheit'', München, 1905, S. 91; cf. S. 173, 175). | |||

The agnostic calls our materialist view of necessity “transcendental,” for from the standpoint of Kantian and Humean “school wisdom,” which Willy does not reject but only furbishes up, any recognition of objective reality given us in experience is an illicit “transcendence.” | |||

Among the French writers of the philosophical trend we are analysing, we find Henri Poincaré constantly straying into this same path of agnosticism. Henri Poincaré is an eminent physicist but a poor philosopher, whose errors Yushkevich, of course, declared to be the last word of recent positivism, so “recent,” indeed, that it even required a new “ism,” ''viz''., empirio-symbolism. For Poincaré (with whose views as a whole we shall deal in the chapter on the new physics), the laws of nature are symbols, conventions, which man creates for the sake of “''convenience''.” “The only true objective reality is the internal harmony of the world.” By “objective,” Poincaré means that which is generally regarded as valid, that which is accepted by the majority of men, or by all[2] ; that is to say, in a purely subjectivist manner he destroys objective truth, as do all the Machians. And as regards “harmony,” he categorically declares in answer to the question whether it exists ''outside of us''—"undoubtedly, no.” It is perfectly obvious that the new terms do not in the least change the ancient philosophical position of agnosticism, for the essence of Poincaré’s “original” theory amounts to a denial (although he is far from consistent) of objective reality and of objective law in nature. It is, therefore, perfectly natural that in contradistinction to the Russian Machians, who accept new formulations of old errors as the latest discoveries, the German Kantians greeted such views as a conversion to their own views, ''i.e.''., to agnosticism, on a fundamental question of philosophy. “The French mathematician Henri Poincaré,” we read in the work of the Kantian, Philipp Frank, “holds the point of view that many of the most general laws of theoretical natural science (''e''.''g''., the law of inertia, the law of the conservation of energy, etc.), of which it is so often difficult to say whether they are of empirical or of ''a priori'' origin, are, in fact, neither one nor the other, but are purely conventional propositions depending upon human discretion. . . .” “Thus [exults the Kantian] the latest ''Naturphilosophie'' unexpectedly renews the fundamental idea of critical idealism, namely, that experience merely fills in a framework which man brings with him from nature. . . ."<sup>[3]</sup> | |||

We quote this example in order to give the reader a clear idea of the degree of naïveté of our Yushkeviches, who take a “theory of symbolism” for something genuinely ''new'', whereas philosophers in the least versed in their subject say plainly and explicitly: he has become converted to the standpoint of critical idealism! For the essence of this point of view does not necessarily lie in the repetition of Kant’s formulations, but in the recognition of the fundamental idea ''common'' to both Hume and Kant, ''viz''., the denial of objective law in nature and the deduction of particular “conditions of experience,” particular principles, postulates and propositions ''from the subject'', from human consciousness, and not from nature. Engels was right when he said that it is not important to which of the numerous schools of materialism or idealism a particular philosopher belongs, but rather whether he takes nature, the external world, matter in motion, or spirit, reason, consciousness, etc., as primary. | |||

Another characterisation of Machism on this question, in contrast to the other philosophical lines, is given by the expert Kantian, E. Lucka. On the question of causality “Mach entirely agrees with Hume."<sup>[4]</sup> “P. Volkmann derives the necessity of thought from the necessity of the processes of nature—a standpoint that, in contradistinction to Mach and in agreement with Kant, recognises the fact of necessity; but contrary to Kant, it seeks the source of necessity not in thought, but in the processes of nature” (p. 424). | |||

Volkmann is a physicist who writes fairly extensively on epistemological questions, and who tends, as do the vast majority of scientists, to materialism, albeit an inconsistent, timid, and incoherent materialism. The recognition of necessity in nature and the derivation from it of necessity in thought is materialism. The derivation of necessity, causality, law, etc., from thought is idealism. The only inaccuracy in the passage quoted is that a total denial of all necessity is attributed to Mach. We have already seen that this is not true either of Mach or of the empirio-critical trend generally, which, having definitely departed from materialism, is inevitably sliding into idealism. | |||

It remains for us to say a few words about the Russian Machians in particular. They would like to be Marxists; they have all “read” Engels’ decisive demarcation of materialism from the Humean trend; they could not have failed to learn both from Mach himself and from everybody in the least acquainted with his philosophy that Mach and Avenarius follow the line of Hume. Yet they are all careful ''not to say a single word'' about Humism and materialism on the question of causality! Their confusion is utter. Let us give a few examples. Mr. P. Yushkevich preaches the “new” empirio-symbolism. The “sensations of blue, hard, etc.—these supposed data of pure experience” and “the creations supposedly of pure reason, such as a chimera or a chess game"—all these are “empirio-symbols” (''Studies'', ''etc''., p. 179). “Knowledge is empirio-symbolic, and as it develops leads to empirio-symbols of a greatet degree of symbolisation. . . . The so-called laws of nature . . . are these empirio-symbols. . .” (''ibid''.). “The so-called true reality, being in itself, is that infinite [a terribly learned fellow, this Mr. Yushkevich!] ultimate system of symbols to which all our knowledge is striving” (p. 188). “The stream of experience . . . which lies at the foundation of our knowledge is . . . irrational . . . illogical” (pp. 187, 194). Energy “is just as little a thing, a substance, as time, space, mass and the other fundamental concepts of science: energy is a constancy, an empirio-symbol, like other empirio-symbols that for a time satisfy the fundamental human need of introducing reason, Logos, into the irrational stream of experience” (p. 209). | |||

Clad like a harlequin in a garish motley of shreds of the “latest” terminology, there stands before us a subjective idealist, for whom the external world, nature and its laws are all symbols of our knowledge. The stream of experience is devoid of reason, order and law: our knowledge brings reason into it. The celestial bodies are symbols of human knowledge, and so is the earth. If science teaches us that the earth existed long before it was possible for man and organic matter to have appeared, we, you see, have changed all that! The order of the motion of the planets is brought about ''by us'', it is a product of our knowledge. And sensing that human reason is being inflated by such a philosophy into the author and founder of nature, Mr. Yushkevich puts alongside of reason the word ''Logos'', that is, reason in the abstract, not reason, but Reason, not a function of the human brain, but something existing prior to any brain, something divine. The last word of “recent positivism” is that old formula of fideism which Feuerbach had already exposed. | |||

Let us take A. Bogdanov. In 1899, when he was still a semi-materialist and had only just begun to go astray under the influence of a very great chemist and very muddled philosopher, Wilhelm Ostwald, he wrote: “The general causal connection of phenomena is the last and best child of human knowledge; it is the universal law, the highest of those laws which, to express it in the words of a philosopher, human reason dictates to nature” (''Fundamental Elements'', ''etc''., p. 41). | |||

Allah alone knows from what source Bogdanov took this reference. But the fact is that “the words of a philosopher” trustingly repeated by the “Marxist"—are the words of Kant. An unpleasant event! And all the more unpleasant in that it cannot even be explained by the “mere” influence of Ostwald. | |||

In 1904, having already managed to discard both natural-historical materialism and Ostwald, Bogdanov wrote: “. . . Modern positivism regards the law of causality only as a means of cognitively connecting phenomena into a continuous series, only as a form of co-ordinating experience” (''From the Psychology of Society'', p. 207). Bogdanov either did not know, or would not admit, that this modern positivism is agnosticism and that it denies the objective necessity of nature, which existed prior to, and outside of, “knowledge” and man. He accepted on faith what the German professors called “modern positivism.” Finally, in 1905, having passed through all the previous stages and the stage of empirio-criticism, and being already in the stage of “empirio-monism,” Bogdanov wrote: “Laws do not belong to the sphere of experience . . . they are not given in it, but are created by thought as a means of organising experience, of harmoniously co-ordinating it into a symmetrical whole” (''Empirio-Monism'', I, p. 40). “Laws are abstractions of knowledge; and physical laws possess physical properties just as little as psychological laws possess psychical properties” (''ibid''.). | |||

And so, the law that winter succeeds autumn and the spring winter is not given us in experience but is created by thought as a means of organising, harmonising, co-ordinating. . . what with what, Comrade Bogdanov? | |||

“Empirio-monism is possible only because knowledge actively harmonises experience, eliminating its infinite contradictions, creating for it universal organising forms, replacing the primeval chaotic world of elements by a derivative, ordered world of relations” (p. 57). That is not true. The idea that knowledge can “create” universal forms, replace the primeval chaos by order, etc., is the idea of idealist philosophy. The world is matter moving in conformity to law, and our knowledge, being the highest product of nature, is in a position only to ''reflect'' this conformity to law. | |||

In brief, our Machians, blindly believing the “recent” reactionary professors, repeat the mistakes of Kantian and Humean agnosticism on the question of causality and fail to notice either that these doctrines are in absolute contradiction to Marxism, ''i.e.''., materialism, or that they themselves are rolling down an inclined plane towards idealism. | |||

==== The “principle of economy of thought” and the problem of the “unity of the world” ==== | ==== The “principle of economy of thought” and the problem of the “unity of the world” ==== | ||

“The principle of ‘the least expenditure of energy,’ which Mach, Avenarius and many others made the basis of the theory of knowledge, is . . . unquestionably a ‘Marxist’ tendency in epistemology.” | |||

So Bazarov asserts in the ''Studies'', ''etc''., page 69. | |||

There is “economy” in Marx; there is “economy” in Mach. But is it indeed “unquestionable” that there is even a shadow of resemblance between the two? | |||

Avenarius’ work, ''Philosophie als Denken der Welt gemäss dem Prinzip des Kleinsten Kraftmasses'' (1876), as we have seen, applies this “principle” in such a way that in the name of “economy of thought” sensation alone is declared to exist. Both causality and “substance” (a word which the professorial gentlemen, “for the sake of importance,” prefer to the clearer and more exact word: matter) are declared “eliminated” on the same plea of economy. Thus we get sensation without matter and thought without brain. This utter nonsense is an attempt to smuggle in ''subjective idealism'' under a new guise. That ''such'' precisely is the character of this basic work on the celebrated “economy of thought” is, as we have seen, ''generally acknowledged'' in philosophical literature. That our Machians did not notice the subjective idealism under the “new” flag is a fact belonging to the realm of curiosities. | |||

In the ''Analysis of Sensations'' (Russ. trans., p. 49), Mach refers incidentally to his work of 1872 on this question. And this work, as we have seen, propounds the standpoint of pure subjectivism and reduces the world to sensations. Thus, both the fundamental works which introduce this famous “principle” into philosophy expound idealism! What is the reason for this? The reason is that if the principle of economy of thought is really made “''the basis'' of the theory of knowledge,” it can lead to ''nothing but'' subjective idealism. That it is more “economical” to “think” that only I and my sensations exist is unquestionable, provided we want to introduce such an absurd conception into ''epistemology''. | |||

Is it “more economical” to “think” of the atom as indivisible, or as composed of positive and negative electrons? Is it “more economical” to think of the Russian bourgeois revolution as being conducted by the liberals or as being conducted against the liberals? One has only to put the question in order to see the absurdity, the subjectivism of applying the category of “the economy of thought” ''here''. Human thought is “economical” only when it ''correctly'' reflects objective truth, and the criterion of this correctness is practice, experiment and industry. Only by denying objective reality, that is, by denying the ''foundations'' of Marxism, can one seriously speak of economy of thought in the theory of knowledge. | |||

If we turn to Mach’s later works, we shall find in them an ''interpretation'' of the celebrated principle which frequently amounts to its complete denial. For instance, in the ''Wärmelehre'' Mach returns to his favourite idea of “the economical nature” of science (2nd German ed., p. 366). But there he adds that we engage in an activity not for the sake of the activity (p. 366; repeated on p. 391): “the purpose of scientific activity is to present the fullest . . . most tranquil . . . picture possible of the world” (p. 366). If this is the case, the “principle of economy” is banished not only from the basis of epistemology, but virtually from epistemology generally. When one says that the purpose of science is to present a the picture of the world (tranquillity is entirely beside the point here), one is repeating the materialist point of view. When one says this, one is admitting the objective reality of the world in relation to our knowledge, of the model in relation to the picture. To talk of ''economy'' of thought in ''such'' a connection is merely to use a clumsy and ridiculously pretentious ''word'' in place of the word “correctness.” Mach is muddled here, as usua], and the Machians behold the muddle and worship it! | |||

In ''Knowledge and Error'', in the chapter entitled “Illustrations of Methods of Investigation,” we read the following: | |||

“The ‘complete and simplest description’ (Kirchhoff, 1874), the ‘economical presentation of the factual’ (Mach, 1872), the ‘concordance of thinking and being and the mutual concordance of the processes of thought’ (Grassmann, 1844)—all these, with slight variations, express one and the same thought.” | |||

Is this not a model of confusion? “Economy of thought,” from which Mach in 1872 inferred that sensations ''alone'' exist (a point of view which he himself subsequently was obliged to acknowledge an idealist one), is declared to be ''equivalent'' to the purely materialist dictum of the mathematician Grassmann regarding the necessity of co-ordinating thinking and ''being'', equivalent to the simplest ''description'' (of an ''objective reality'', the existence of which it never occurred to Kirchhoff to doubtl). | |||

''Such'' an application of the principle of “economy of thought” is but an example of Mach’s curious philosophical waverings. And if such curiosities and lapses are eliminated, the idealist character of “the principle of the economy of thought” becomes unquestionable. For example, the Kantian Hönigswald, controverting the philosophy of Mach, greets his “principle of economy” as an ''approach'' to the “Kantian circle of ideas” (Dr. Richard Hönigswald, ''Zur Kritik der Machschen Philosophie'' [''A Critique of Mach’s Philosophy''], Berlin, 1903, S. 27). And, in truth, if we do not recognise the objective reality given us in our sensations, whence are we to derive the “principle of economy” if not ''from the subject''? Sensations, of course, do not contain any “economy.” Hence, thought gives us something which is not contained in sensations! Hence, the “principle of economy” is not taken from experience (''i.e.''., sensations), but precedes all experience and, like a Kantian category, constitutes a logical condition of experience. Hönigswald quotes the following passage from the ''Analysis of Sensations'': “We can from our bodily and spiritual stability infer the stability, the uniqueness of determination and the uniformity of the processes of nature” (Russ. trans., p. 281). And, indeed, the subjective-idealist character of such propositions and the kinship of Mach to Petzoldt, who has gone to the length of apriorism, are beyond all shadow of doubt. | |||

In connection with “the principle of the economy of thought,” the idealist Wundt very aptly characterised Mach as “Kant turned inside out” (''Systematische Philosophie'', Leipzig, 1907, S. 128). Kant has ''a priori'' and experience, Mach has experience and ''a priori'', for Mach’s principle of the econ omy of thought is essentially apriorism (p. 130). The con nection (''Verknüpfung'') is either in things, as an “objective law of nature [and this Mach emphatically rejects], or else it is a subjective principle of description” (p. 130). The principle of economy with Mach is subjective and ''kommt wie aus der Pistole geschossen''—appears nobody knows whence—as a teleological principle which may have a diversity of meanings (p. 131). As you see, experts in philosophical terminology are not as naïve as our Machians, who are blindly prepared to believe that a “new” term can eliminate the contrast between subjectivism and objectivism, between idealism and materialism. | |||

Finally, let us turn to the English philosopher James Ward, who without circumlocution calls himself a spiritualist monist. He does not controvert Mach, but, as we shall see later, utilises the entire Machian trend in physics in his fight against materialism. And he definitely declares that with Mach “the criterion of simplicity . . . is in the main subjective, not objective” (''Naturalism and Agnosticism'', Vol. I, 3rd ed., p. 82). | |||

That the principle of the economy of thought as the basis of epistemology pleased the German Kantians and English spiritualists will not seem strange after all that has been said above. That people who are desirous of being Marxists should link the political economy of the materialist Marx with the epistemological economy of Mach is simply ludicrous. | |||

It would be appropriate here to say a few words about “the unity of the world.” On this question Mr. P. Yushkevich strikingly exemplifies—for the thousandth time perhaps—the abysmal confusion created by our Machians. Engels, in his ''Anti-Dühring'', replies to Dühring, who had deduced the unity of the world from the unity of thought, as follows: “The real unity of the world consists in its materiality, and this is proved not by a few juggling phrases, but by a long and protracted development of philosophy and natural science” (p. 31).<sup>[1]</sup> Mr. Yushkevich cites this passage and retorts: “First of all it is not clear what is meant here by the assertion that ‘the unity of the world consists in its materiality’” (''op''. ''cit''., p. 52). | |||

Charming, is it not? This individual undertakes publicly to prate about the philosophy of Marxism, and then declares that the most elementary propositions of materialism are “not clear” to him! Engels showed, using Dühring as an example, that any philosophy that claims to be consistent can deduce the unity of the world either from thought—in which case it is helpless against spiritualism and fideism (''Anti-Dühring'', p. 30), and its arguments inevitably become mere phrase-juggling—or from the objective reality which exists outside us, which in the theory of knowledge has long gone under the name of matter, and which is studied by natural science. It is useless to speak seriously to an individual to whom such a thing is “not clear,” for he says it is “not clear” in order fraudulently to evade giving a genuine answer to Engels’ clear materialist proposition. And, doing so, he talks pure Dühringian nonsense about “the cardinal postulate of the fundamental homogeneity and connection of being” (Yushkevich, ''op''. ''cit''., p. 51), about postulates being “propositions” of which “it would not be exact to say that they have been deduced from expericnce, since scientific experience is possible only because they are made the basis of investigation” (''ibid''.). This is nothing but twaddle, for if this individual had the slightest respect for the printed word he would detect the ''idealist'' character in general, and the ''Kantian'' character in particular of the idea that there can be postulates which are not taken from experience and without which experience is impossible. A jumble of words culled from diverse books and coupled with the obvious errors of the materialist Dietzgen—such is the “philosophy” of Mr. Yushkevich and his like. | |||

Let us rather examine the argument for the unity of the world expounded by a serious empirio-criticist, Joseph Petzoldt. Section 29, Vol. II, of his ''Introduction'' is termed: “The Tendency to a Uniform (''einheitlich'') Conception of the Realm of Knowledge; the Postulate of the Unique Determination of All That Happens.” And here are a few samples of his line of reasoning: “. . . Only in ''unity'' can one find that natural end beyond which no thought can go and in which, consequently, thought, if it takes into consideration all the facts of the given sphere, can reach quiescence” (p. 79). “. . . It is beyond doubt that nature does not always respond to the demand for ''unity'', but it is equally beyond doubt that in many cases it already satisfies the demand for ''quiescence'' and it must be held, in accordance with all our previous investigations, that nature in all probability will satisfy this demand in the future in all cases. Hence, it would be more correct to describe the actual soul behaviour as a striving for states of stability rather than as a striving for unity. . . . The principle of the states of stability goes farther and deeper. . . . Haeckel’s proposal to put the kingdom of the protista alongside the plant and animal kingdom is an untenable solution for it creates two new difficulties in place of the former one difficulty: while formerly the boundary between the plants and animals was doubtful, now it becomes impossible to demarcate the protista from both plants and animals. . . . Obviously, such a state is not final (''endgültig''). Such ''ambiguity'' of concepts must in one way or another be eliminated, if only, should there be no other means, by an agreement between the specialists, or by a majority vote” (pp. 80-81). | |||

Enough, I think? It is evident that the ernpirio-criticist Petzoldt is ''not one whit'' better than Dühring. But we must be fair even to an adversary; Petzoldt at least has sufficient scientific integrity to reject materialism as a philosophical trend ''unflinchingly and decisively'' in all his works. At least, he does not humiliate himself to the extent of posing as a materialist and declaring that the most elementary distinction between the fundamental philosophical trends is “not clear.” | |||

==== Space and time ==== | ==== Space and time ==== | ||

Recognising the existence of objective reality, ''i.e.''., matter in motion, independently of our mind, materialism must also inevitably recognise the objective reality of time and space, in contrast above all to Kantianism, which in this question sides with idealism and regards time and space not as objective realities but as forms of human understanding. The basic difference between the two fundamental philosophical lines on this question is also quite clearly recognised by writers of the most diverse trends who are in any way consistent thinkers. Let us begin with the materialists. | |||

“Space and time,” says Feuerbach, “are not mere forms of phenomena but essential conditions (Wesensbedingungen) . . . of being” (''Werke'', II, S. 332). Regarding the sensible world we know through sensations as objective reality, Feuerbach naturally also rejects the phenomenalist (as Mach would call his own conception) or the agnostic (as Engels calls it) conception of space and time. Just as things or bodies are not mere phenomena, not complexes of sensations, but objective realities acting on our senses, so space and time are not mere forms of phenomena, but objectively real forms of being. There is nothing in the world but matter in motion, and matter in motion cannot move otherwise than in space and time. Human conceptions of space and time are relative, but these relative conceptions go to compound absolute truth. These relative conceptions, in their development, move towards absolute truth and approach nearer and nearer to it. The mutability of human conceptions of space and time no more refutes the objective reality of space and time than the mutability of scientific knowledge of the structure and forms of matter in motion refutes the objective reality of the external world. | |||

Engels, exposing the inconsistent and muddled materialist Dühring, catches him on the very point where he speaks of the change in the ''idea'' of time (a question beyond controversy for contemporary philosophers of any importance even of the ''most diverse'' philosophical trends) but ''evades'' a direct answer to the question: are space and time real or ideal, and are our relative conceptions of space and time ''approximations'' to objectively real forms of being, or are they only products of the developing, organising, harmonising, etc., human mind? This and this alone is the basic epistemological problem on which the truly fundamental philosophical trends are divided. Engels, in ''Anti-Dühring'', says: “We are here not in the least concerned with what ideas change in Herr Dühring’s head. The subject at issue is not the ''idea'' of time, but ''real'' time, which Herr Dühring cannot rid him self of so cheaply [''i.e.''., by the use of such phrases as the mutability of our conceptions]” (''Anti-Dühring'', 5th Germ. ed., S. 41).[5] | |||

This would seem so clear that even the Yushkeviches should be able to grasp the essence of the matter! Engels sets up against Dühring the proposition of the ''reality'', ''i.e.''., objective reality, of time which is generally accepted by and obvious to every materialist, and says that ''one cannot escape'' a direct affirmation or denial of this proposition merely by talking of the change in the ''ideas'' of time and space. The point is not that Engels denies the necessity and scientific value of investigations into the change and development of our ideas of time and space, but that we should give a consistent answer to the epistemological question, ''viz''., the question of the source and significance of human knowledge in general. Any moderately intelligent philosophical idealist—and Engels when he speaks of idealists has in mind the great consistent idealists of classical philosophy—will readily admit the development of our ideas of time and space; he would not cease to be an idealist for thinking, for example, that our developing ideas of time and space are approaching towards the absolute idea of time and space, and so forth. It is impossible to hold consistently to a standpoint in philosophy which is inimical to all forms of fideism and idealism if we do not definitely and resolutely recognise that our developing notions of time and space ''reflect'' an objectively real time and space; that here, too, as in general, they are approaching objective truth. | |||

“The basic forms of all being,” Engels admonishes Dühring, “are space and time, and existence out of time is just as gross an absurdity as existence out of space” (''op''. ''cit''.). | |||

Why was it necessary for Engels, in the first half of the quotation, to repeat Feuerbach almost literally and, in the second, to recall the struggle which Feuerbach fought so successfully against the gross absurdities of theism? Because Dühring, as one sees from this same chapter of Engels’, could not get the ends of his philosophy to meet without resorting now to the “final cause” of the world, now to the “initial impulse” (which is another expression for the concept “God,” Engels says). Dühring no doubt wanted to be a materialist and atheist no less sincerely than our Machians want to be Marxists, but he ''was unable'' consistently to develop the philosophical point of view that would really cut the ground from under the idealist and theist absurdity. Since he did not recognise, or, at least, did not recognise clearly and distinctly (for he wavered and was muddled on this question), the objective reality of time and space, it was not accidental but inevitable that Dühring should slide down an inclined plane to “final causes” and “initial impulses"; for he had deprived himself of the objective criterion which prevents one going beyond the bounds of time and space. If time and space are ''only'' concepts, man, who created them is justified in ''going beyond their bounds'', and bourgeois professors are justified in receiving salaries from reactionary governments for defending the right to go beyond these bounds, for directly or indirectly defending medieal “absurdity.” | |||

Engels pointed out to Dühring that denial of the objective reality of time-and space is theoretically philosophical confusion, while practically it is capitulation to, or impotence in face of, fideism. | |||

Behold now the “teachings” of “recent positivism” on this subject. We read in Mach: “Space and time are well ordered (''wohlgeordnete'') systems of series of sensations” (''Mechanik'', 3. Auflage, S. 498). This is palpable idealist nonsense, such as inevitably follows from the doctrine that bodies are complexes of sensations. According to Mach, it is not man with his sensations that exists in space and time, but space and time that exist in man, that depend upon man and are generated by man. He feels that he is falling into idealism, and “resists” by making a host of reservations and, like Dühring, burying the question under lengthy disquisitions (see especially ''Knowledge and Error'') on the mutability of our conceptions of space and time, their relativity, and so forth. But this does not save him, and cannot save him, for one can really overcome the idealist position on this question only by recognising the objective reality of space and time. And this Mach will not do at any price. He constructs his epistemological theory of time and space on the principle of relativism, and that is all. In the very nature of things such a construction can lead to nothing but subjective idealism, as we have already made clear when speaking of absolute and relative truth. | |||