More languages

More actions

(Mechanism) Tag: Visual edit |

mNo edit summary Tag: Visual edit |

||

| Line 42: | Line 42: | ||

[[Category:Russians by descent]] | [[Category:Russians by descent]] | ||

[[Category:Russians]] | [[Category:Russians]] | ||

{{DEFAULTSORT:Bukharin, Nikolai}} | |||

Revision as of 19:33, 17 June 2024

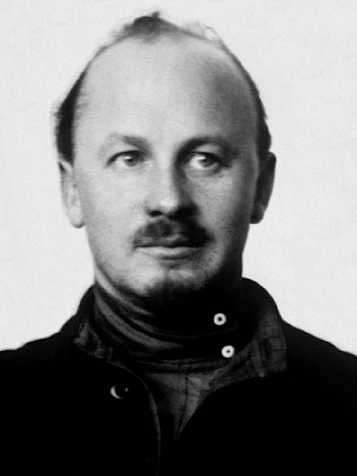

Nikolai Bukharin Никола́й Буха́рин | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 9 October 1888 Moscow, Russian Empire |

| Died | 15 March 1938 Moscow, RSFSR, Soviet Union |

| Cause of death | Execution |

| Nationality | Russian |

| Political orientation | Opportunism |

Nikolai Ivanovich Bukharin (9 October 1888 – 15 March 1938) was a Russian revolutionary and communist politician. After the October Revolution, he initially became a member of a left-communist opposition group with Preobrazhensky that supported Trotsky over Lenin. During the New Economic Policy, he became a right-opportunist and supported the bourgeoisie[1] and kulaks. He formed an anti-party bloc with Alexei Rykov and Mikhail Tomsky.[2] In early 1929, Bukharin confessed to Jules Humbert-Droz, a Swiss Social-Democrat and a friend, that the bloc was forced to resort to terrorism in order to remove Stalin for the lack of public or Party support.[3]

Political career

Revolution

In 1918, Bukharin planned to arrest Lenin, Stalin, and Sverdlov and create a new government of SRs and left communists.[4]

1930s

Bukharin was the chief editor of the government newspaper Izvestiya during the early 1930s. He met with the Menshevik Nikolayevsky in Paris to buy some manuscripts of Marx and Engels and admitted that he saw Stalin as "not a man, a devil."[4]

Political positions

Bukharin believed the peasants were aligned with the bourgeoisie and supported the imperialist World War.[5] He prioritized light industry over heavy industry.[4]

Collectivization

Bukharin believed that collectivization was not possible at the planned rate and that middle and poor peasants did not want to collectivize.[6] After collectivization was completed, he wanted to reverse it.[4]

Elections

Bukharin wanted to create another political party composed of intellectuals to run against the CPSU in elections. He also advocated for other opposition parties including nationalist parties.[4]

Philosophical views

Bukharin promoted the anti-dialectical theory of mechanism, which claimed that systems exist at equilibrium and cannot change or move without external influence. In 1921, Lenin criticized him for not understanding dialectics. The April 1929 meeting of the Second All-Union Conference of Marxist–Leninist Scientific Institutions rejected mechanism.[7]

Execution

Bukharin was executed in 1937 after the Moscow Trials revealed that he had joined an anti-Soviet bloc with Leon Trotsky and Grigory Zinoviev.[8] Grigory Tokaev (an "ultra-conspiratorial" liberal oppositionist)[9] writes in Betrayal of an Ideal that Bukharin had denounced public opposition to Stalin's government in 1935.[10] Tokaev expresses frustration that Kamenev establishes links between himself, Zinoviev, and Bukharin during his 1935 trial, and "thus, in the course of the second Moscow trial, were sewn the seeds of the fourth trial."[11]

References

- ↑ Joseph Stalin (1939). History of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (Bolsheviks): 'The Bolshevik Party in the Period of Transition to the Peaceful Work of Economic Restoration'. [MIA]

- ↑ Joseph Stalin (1939). History of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (Bolsheviks): 'The Bolshevik Party in the Struggle for the Socialist Industrialization of the Country'. [MIA]

- ↑ Jules Humbert-Droz (1929). Nikolai Bukharin on the Use of Individual Terror Against Stalin: 'Courtesy: Jules Humbert-Droz, ‘De Lénin à Staline, Dix Ans Au Service de L’ Internationale Communiste 1921-31’, A la Baconniére, Neuchâtel, 1971, pp. 379-80. Translated from the French by Vijay Singh'.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 “During his trial, Bukharin admitted in front of the tribunal that in 1918, after the Brest-Litovsk Treaty, that there was a plan to arrest Lenin, Stalin and Sverdlov, and to form a new government composed of `left-communists' and Social Revolutionaries. But he firmly denied that there was also a plan to execute them.

`Stalin aimed at one party dictatorship and complete centralisation. Bukharin envisaged several parties and even nationalist parties, and stood for the maximum of decentralisation. He was also in favour of vesting authority in the various constituent republics and thought that the more important of these should even control their own foreign relations. By 1936, Bukharin was approaching the social democratic standpoint of the left-wing socialists of the West.'”

Ludo Martens (1996). Another View of Stalin: 'The Great Purge'. - ↑ Joseph Stalin (1939). History of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (Bolsheviks): 'The Bolshevik Party in the Period of Preparation and Realization of the October Socialist Revolution'. [MIA]

- ↑ Ludo Martens (1996). Another View of Stalin: 'Collectivization' (p. 62). [PDF] Editions EPO. ISBN 9782872620814

- ↑ TheFinnishBolshevik (2022-10-09). "HISTORY OF PHILOSOPHY IN THE USSR: Mechanism VS Dialectics (1920s)" ML-Theory. Archived from the original on 2024-03-16.

- ↑ Joseph Stalin (1939). History of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (Bolsheviks): 'The Bolshevik Party in the Struggle to Complete the Building of the Socialist Society. Introduction of the New Constitution'. [MIA]

- ↑ “from this statement alone my other readers will grasp in what a turgid atmosphere, in what an ultra-conspiratorial manner-- not even knowing one another's characters-- we oppositionists of the U.S.S.R. have to work.”

Grigory Tokaev (1956). Comrade X: 'Terrorism by Judicial Trial' (p. 61). The Harvill Press. - ↑ “This was all typical Bukharin, this notion of working up a general spirit of resistance, without ever a trace of direct organised struggle against the policy of extreme measures. He was ready to talk about a new revolution, yet refused to admit that it was feasible until the masses had acquired a sense of what it all meant. As for us, the younger generation, he urged us to have confidence in ourselves, but he also urged us to have patience. Events were to prove him right in this and, in the long run, we realised that in the early thirties we approached our political problems in a very shallow way. Two years later, in 1934, we attacked Bukharin and his fellows savagely, accusing them of slithering back into the bogs of Stalinism, but eventually we were to understand that they knew far better than we did what was possible and what was not. The fact that at our first meeting he told us nothing could be done to stop forced collectivisation did not mean that he did not condemn it; it merely meant that he was less powerful than we had foolishly thought he was. (168)

[...]

After I came out of hospital I delivered to Bukharin a resolution prepared by my comrades, which described his action as "renegade, capitulatory and treacherous". His only answer was a morose silence.

He had urged us to think for ourselves and to try to bring our influence to bear on public matters; now he himself had turned against the views, the faith he had stirred up. He would like to have regained our confidence, but it was too late. He had allowed himself to be broken. As a political figure he was on the run. The inevitable ending was already in sight. Soon he was to be arrested, charged with a crime he had never committed, and shamefully put to death.

'Learn by my errors," Bukharin had said when I handed him our resolution, "and bear in mind that Stalin always has a dirty trick up his sleeve." Alas, there were too many errors for us to learn from, and we had to look for more reliable models on which to shape our lives than this intelligent but weak man who made so puny a statesman. (284)”

Grigory Tokaev (1955). Betrayal of an Ideal (pp. 168, 284). Indiana University Press. - ↑ Grigory Tokaev (1956). Comrade X: 'Terrorism by Judicial Trial' (p. 59). The Harvill Press.