More languages

More actions

This article is taken in whole or in part from the Great Soviet Encyclopedia.

Maximilien de Robespierre | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Maximilien Marie Isidore de Robespierre May 6, 1758 Arras, France |

| Died | July 28, 1794 (aged 36) Paris, France |

| Cause of death | Execution |

| Nationality | French |

Maximilien Marie Isidore de Robespierre (6 May 1758 – 28 July 1794) also known as Maximilien Robespierre, was a French politician notable for his role before, during and after the bourgeois French Revolution of 1789.

A member of the Jacobin faction of the Montagnards, he was a fierce radical in the context of the class war between bourgeoisie and aristocracy and fought against the Girondins (who wanted to establish a constitutional monarchy) and other parties to their left and right. In this context, he is seen by Marxists as a progressive force for the bourgeois revolution and prevented France from falling back into feudalism.

Biography

Early life

The son of a lawyer, Robespierre studied at the Collège Louis-le-Grand in Paris and later, at the faculty of law at the Sorbonne. As a student, Robespierre was strongly influenced by Enlightenment ideas and especially by Rousseau, whom he regarded as his mentor. In 1781 he became a lawyer in Arras, specializing in political cases. In 1783 he was elected to the Arras Academy of Arts and Sciences.

Political life

Estates general deputy

Robespierre was elected in 1789, in the midst of the revolution against the French monarchy, to represent the Third Estate of Arras as a deputy in the Estates General. In his speeches to the Estates General and later to the Constituent Assembly, Robespierre defended democratic principles and the interests of the people. He criticized the antidemocratic character of certain proposals of the bourgeois liberal majority, such as the distinction between active and passive citizenship; the introduction of a property census, which would create a new “aristocracy of wealth”; and the royal veto.

Adopting a more radical line, Robespierre supported the demands of the peasantry on the most important issue, the agrarian problem. All of his speeches were permeated with the ideas of popular power and political equality—an idea that he consistently developed, addressing the people directly and disregarding his fellow deputies.

From 1790, Robespierre’s popularity increased in democratic circles. He received the support of the Jacobin Club, the Cordeliers, and political clubs in Marseille, Toulon, and several other cities. However, unlike most democrats, he was late in recognizing the necessity of proclaiming a republic. Even during the crisis stemming from the king’s attempt to flee the country in June 1791, Robespierre did not support the demand for a republic, fearing that it would be an aristocratic regime. Moreover, he did not oppose the Le Chapelier Law of June 1791, which was directed against the working class.

Role in the coalition war

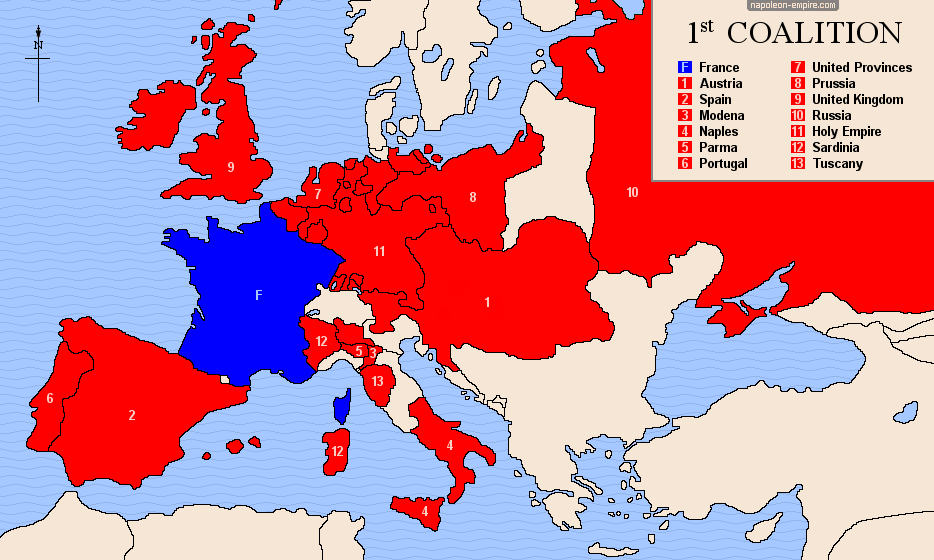

Following the French revolution, European feudal countries were scared that a similar event could befall their nobility. Thus, a coalition of 13 countries formed to invade the fledgling republic and restore the aristocracy.

Characterizing as sheer adventurism the policies of the Girondins, who were propagandizing in favor of revolutionary war in the winter and spring of 1791, Robespierre declared that the foreign counterrevolution could not be vanquished until the revolution had triumphed in France. With the outbreak of war between France and a coalition of absolutist feudal states in the spring of 1792, Robespierre insisted on the use of revolutionary methods of warfare and castigated the Feuillants’ and Girondins’ lack of confidence in the people, expressing his views in Le Défenseur de la constitution (Defender of the Constitution), a weekly that he began publishing in the spring of 1792. In the summer of 1792, Robespierre demanded the dissolution of the Legislative Assembly, which had replaced the Constituent Assembly in the autumn of 1791; the introduction of universal suffrage; and elections to the Convention.

Opposition to the Girondins

Although Robespierre did not participate directly in the popular uprising of Aug. 10, 1792, by August 11 he had been elected a member of the revolutionary Paris Commune.

In September 1792 he was elected to represent Paris in the National Convention, having received more votes than any other candidate. He and Jean-Paul Marat led the struggle against the Girondins and succeeded in having the death penalty enacted for the deposed king, Louis 16th. He was one of the political leaders of the popular insurrection of May 31-June 2, 1793, which overthrew the Girondins.

Robespierre became one of the principal formulators of the revolutionary policies of the Jacobins, who came to power after the Girondins. Among the achievements of the Jacobins were the solution of the agrarian problem by the abolition of feudal landownership, the enactment of the democratic constitution of 1793, and other measures that ensured wide popular support for the Jacobin government.

He provided a theoretical foundation for the new, higher form of organization of revolutionary power that replaced the constitutional regime—the revolutionary democratic dictatorship, the need for which was understood more rapidly and more clearly by Robespierre than by other Jacobin leaders. In a speech to the Convention on Dec. 25, 1793, Robespierre described the essence of revolutionary government: “The revolution is the struggle of freedom against its enemies; the constitution is the regime of a victorious and peaceful freedom” (Izbr. proizv., vol. 3, p. 91, 1965).

End of life

In July 1793, Robespierre became the head of the Committee of Public Safety. He played a crucial role in the mobilization of popular forces and the achievement of victory over foreign and domestic counterrevolution. However, his political activity was marked by contradictions rooted in the very character of the Jacobin dictatorship. His revolutionary traits were intertwined with the limited capacities and duplicity characteristic of bourgeois politicians. For example, Robespierre struggled not only against the followers of Georges Jacques Danton, who attacked the revolutionary government from the right, but also against left-wing social forces, including Pierre-Gaspard Chaumette and his supporters. He also insisted on strictly enforcing a maximum wage, and he upheld other similar measures. Robespierre was mistaken in his attempts to unify the nation around a new, republican religion (the cult of the Supreme Being), the fallacy of which he soon realized.

Although Robespierre was aware of increasing opposition to the Jacobin dictatorship and the futility of his efforts, he did not take effective measures to prevent the conspiracy that was developing against him. He was absent from the Convention for six weeks (until July 26), and at the end of June 1794, he left the Committee of Public Safety. On July 26, 1794, he attempted unsuccessfully to persuade the Convention to censure the conspirators. The counterrevolutionary Thermidor coup (July 27–28, 1794) led to the fall of the Jacobin dictatorship.

Robespierre and his closest supporters were arrested and guillotined without trial.

Period of Terror

The Terror (from French "Terreur") was the name given to the period when Robespierre was on the Committee of Public Safety, from 1793 up until his execution in 1794. This committee was elected by the National convention functioned as the executive branch of the new republic.

One major task of the committee was to prevent the counter-revolution, facing especially uprisings in the south and west of France.

Between September 1793 and February 1794, the revolutionary tribunal in Paris convicted and executed 238 men and 31 women and acquitted 190 persons over a period of 5 months, and that on February 5 there were 5,434 individuals in the prisons in Paris awaiting trial.

The context of the Terror justified the extent of the measures taken (and this is accepted even by bourgeois historians). France was facing a civil war on one hand, and an invasion by the first coalition on the other. Aristocratic elements were picked to be destroyed so as to weaken a possible counter-revolution. At the same time, an economic crisis as well as a food shortage was hitting France and the lowest classes could not afford the items they needed to live. The committee of public safety was established to deal with these crises, and the Terror was decreed in this context to deal specifically with the counter-revolutionary elements: aristocrats and nobles, the clergy, and hoarders.