More languages

More actions

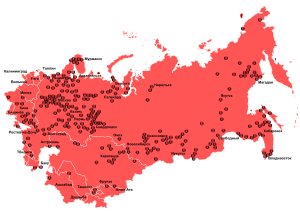

The Main Administration of Camps (Russian: Главное управление лагерей) abbreviated as GULag, was the system of prisons, remote camps, psychiatric hospitals and special laboratories that housed prisoners in the Soviet Union.

After the opening of the USSR archives, it was confirmed most of the prisoners were convicted of regular crimes and were not political prisoners or counterrevolutionaries. At the peak of the GULag system, shortly after the Second World War in 1951, 2.4% of the adult Soviet population was incarcerated, which represented 2.5 million prisoners. For comparison, 2.8% of the United States population is currently incarcerated, millions more than were ever imprisoned in Soviet gulags.[1]

Many gulags were mostly self-sufficient, especially the more remote ones. Most could be compared to small villages or towns, and the less accessible ones did not even need any enclosures such as fences or walls; inmates were free to move around the prison as they pleased. The belief in the USSR was that labour was rehabilitative, and thus putting inmates to work for their benefit as well as the benefit of the collective (the Volga canal for example) was believed to help discourage people from committing crimes.

History

Establishment

the GULag administration was established in 1919. The Soviet Union had inherited the katorga system of the Tsarist empire, including the existing infrastructure, and decided to use it as its basis for their own penal institution.

Purges

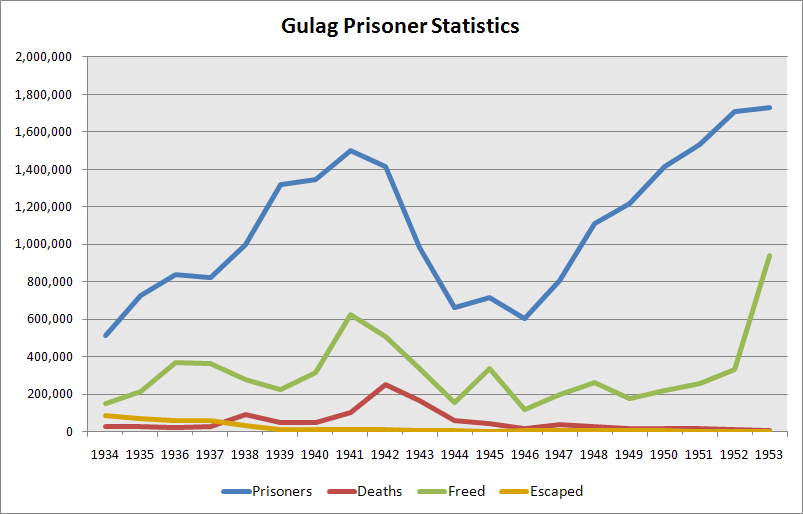

There were 510,307 gulag prisoners in 1934, including 127,000 to 170,000 political prisoners. The number of prisoners rose to 1,317,195 in 1939, and there were about 116,000 deaths in the camps.[2]

Second World War period

During the Second World War, the gulag population peaked, as did its mortality rate. As the whole country was focused on a war economy and fighting a devastating invasion from Nazi Germany, sacrifices had to be made and many in the gulags felt it harshly (as did civilian populations on the frontlines that could not be evacuated in time).[2]

Post-war period

In 1954, under his anti-Stalin campaign, Khrushchev released many gulag inmates under the guise of them being falsely convicted. After the opening of the USSR archives however, it was found most of those inmates were common criminals that were released back into the general population.

Conditions in the gulag

Working conditions

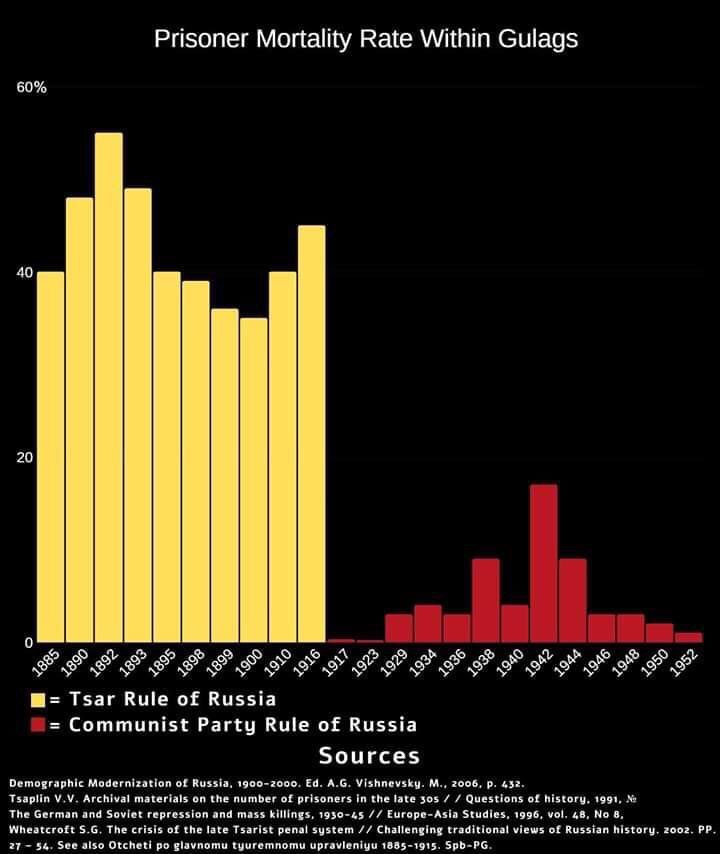

Inmates worked 10-hour days until 1954, when the work day was reduced to 8 hours. After 1954, Prisoners who worked very productively could have their sentences reduced by up to half and were given extra food or money.[1] The death rate in the gulags was highest during the Second World War, but was always lower than the death rate in the Tsarist prison camps that had existed before the revolution, which had a death rate of over 40%.[3]

In popular fiction

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, a counter-revolutionary anti-Semite pogromist, spent some time in Gulags. After his release, he fled the USSR and wrote a fictional tale called The gulag archipelago to garner support and funding abroad. Notably, his wife Natalya said that:

The subject of Gulag Archipelago, as I felt at the moment when he was writing it, is not in fact the life of the country and not even the life of the camps but the folklore of the camps[4]

She also claimed that she typed part of the book for Aleksandr when they were still living together.[4]

Notes

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Saed Teymuri (2018-10-31). "The Truth about the Soviet Gulag - Surprisingly Revealed by the CIA" The Stalinist Katyusha. Archived from the original on 2019-04-01. Retrieved 2022-09-11.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Ludo Martens (1996). Another View of Stalin: 'The Great Purge' (p. 169). [PDF] Editions EPO. ISBN 9782872620814

- ↑ Anatoly Vishnevsky (2006). The Demographic Modernization of Russia, 1900-2000 (p. 432). Moscow. ISBN 5983790420

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Solzhenitsyn's Ex‐Wife Says ‘Gulag’ Is ‘Folklore’" (1974-02-06). New York Times.