More languages

More actions

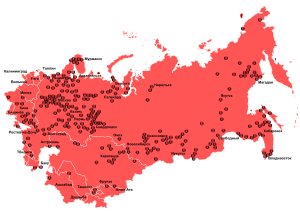

The Main Administration of Camps (Russian: Главное управление лагерей) abbreviated as GULag, was the system of prisons, remote camps, psychiatric hospitals and special laboratories that housed prisoners and fulfilled their penal sentences in the Soviet Union.

Many gulags were mostly self-sufficient, especially the more remote ones. Most could be compared to small villages or towns, and the less accessible ones did not even need any enclosures such as fences or walls; inmates were free to move around the prison as they pleased. The belief in the USSR was that labour was rehabilitative, and thus putting inmates to work for their benefit as well as the benefit of the collective (the building of the Volga canal, for example) was believed to help discourage people from committing crimes.[1]

History[edit | edit source]

Establishment[edit | edit source]

The GULag administration was established in 1919. The Soviet Union had inherited the katorga system of the Tsarist empire, including the existing infrastructure, and decided to use it as the basis for its own penal institution.[2]

Second World War[edit | edit source]

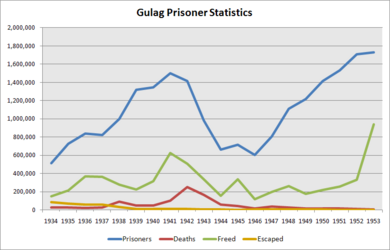

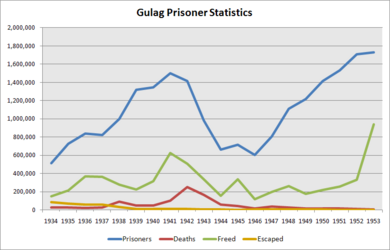

During the Second World War, the GULag population peaked, as did its mortality rate. As the whole country was focused on a war economy and fighting a devastating invasion from Nazi Germany, sacrifices had to be made, and many in the gulags felt it harshly (as did the civilian population).[3]

Post-war period[edit | edit source]

In 1953 and 1954, under his anti-Stalin campaign, Khrushchev released many GULag inmates under the guise of them being falsely convicted. After the opening of the USSR archives, however, it was found that most of those inmates were common criminals who were released back into the general population. In 1953, amnesty was given to 70% of the "ordinary criminals" of a sample camp studied by the CIA. Within the next 3 months, most of them were re-arrested for committing new crimes.[4]

Conditions[edit | edit source]

In 1957 CIA document (which was declassified in 2010) titled “Forced Labor Camps in the USSR: Transfer of Prisoners between Camps” revealed that prisoners were well fed, compensated wages proportionate to their work, with hours comparable to that of free workers, and hard work was rewarded with reduced sentences. 70% of the prisoners were granted amnesty in one year, but most of them were re-arrested for committing new crimes.[5][6] In many ways, including competitive wages and incentives, the prison labor blurred the lines between free work and forced labor.[7]

In 1921, while the civil war ravaged the yet-nascent USSR, we can observe the conditions of the Butyrka prison in Moscow: the prisoners organized the GULag, they organized morning gymnastic sessions, they founded an orchestra, a chorus, a library, and a club where they read foreign journals. There was a prisoners' council too, which occupied itself with the assignment of cells. One inmate remarked that they "strolled along the corridors as if they were boulevards," another one stating, "Can’t they even lock us up seriously?"[8]

Working conditions[edit | edit source]

Inmates worked 10-hour days until 1954, when the work day was reduced to 8 hours. After 1954, prisoners who worked very productively could have their sentences reduced by up to half and were given extra food or money.[9]

Food[edit | edit source]

Until 1952, all prisoners received 122 grams of grain, 10 grams of flour, 20 grams of sugar, 75 grams of fish, 500 grams of potatoes and vegetables, 15 grams of fat, 45 grams of meat, and 650 grams of bread each day. Prisoners who overfulfilled the quota by 100% or more could receive extra bread and sugar.[9]

Deaths[edit | edit source]

On average, 4% of inmates died every year. This figure includes executions and people who died of natural causes. As the death rate was significantly higher during the Second World War, only 2.5% died each year during peacetime.[1][10]

Scale[edit | edit source]

Solzhenitsyn estimated that over 66 million people were victims of the Soviet Union’s forced labor camp system over the course of its existence from 1918 to 1956. With the collapse of the USSR and the opening of the Soviet archives, researchers browsed archival evidence to prove or disprove these claims. They found that in january 1939 the prisoner population was just 2 million out of a population of 168 million (roughly 1.2% of the population).[11]

After the opening of the USSR archives in the early 1990s, it was confirmed that most of the prisoners were convicted of regular crimes and were not political prisoners or counterrevolutionaries. At the peak of the GULag system, shortly after the Second World War in 1951, 2.4% of the adult Soviet population was entangled in the system in some way.[12][4] 20 to 40% of prisoners were released every year.[1]

There were 510,307 GULag prisoners in 1934, including 127,000 to 170,000 political prisoners. The number of prisoners rose to 1,317,195 in 1939, and there were about 116,000 deaths in the camps.[3]

Origins of Anti-Soviet myths[edit | edit source]

Fictional books that were passed off as fact were the origin of sensationalism about the GULag system:

Robert Conquest’s The Great Terror (1968) laid the groundwork for Soviet fearmongering, and was based largely off of defector testimony. Robert Conquest worked for the British Foreign Office’s Information Research Department (IRD), which was a secret Cold War propaganda department, created to publish anti-communist propaganda; to provide support and information to anti-communist politicians, academics, and writers; and to use weaponised information and disinformation and “fake news” to attack not only its original targets but also certain socialists and anti-colonial movements.[13]

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, an anti-communist author and dissident directly responsible for many of the myths and harrowing tales about the GULags, served in the Soviet penal system from 1945 to 1953. After his release, he published the infamous fiction novel The Gulag Archipelago to garner support and funding abroad. It is notable that, according to his ex-wife, Natalya Reshetovskaya, who claimed to have typed part of the book when they were still living together:

The subject of Gulag Archipelago, as I felt at the moment when he was writing it, is not in fact the life of the country and not even the life of the camps but the folklore of the camps[14]

Anne Applebaum’s Gulag: A History of the Soviet Camps (2003) draws directly from The Gulag Archipelago and reiterates its message.[15] Anne is a member of the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR)[16] and was on the board of the National Endowment for Democracy (NED)[17], two infamous pieces of the ideological apparatus of the ruling class in the United States, whose primary aim is to promote the interests of American Imperialism around the world.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Austin Murphy (2000). The Triumph of Evil: 'The Documented Facts about Eastern Europe and Communism'. [PDF] Fucecchio: European Press Academic Publishing. ISBN 8883980026

- ↑ “The prisoners were allowed free run of the prison. They organized morning gymnastic

sessions, founded an orchestra and a chorus, created a “club” supplied with foreign journals and a good library. According to tradition―dating back to pre-revolutionary days―every prisoner left behind his books after he was freed. A prisoners’ council assigned everyone cells, some of which were beautifully supplied with carpets on the floors and walls. Another prisoner remembered that “we strolled along the corridors as if they were boulevards.” To Babina, prison life seemed unreal: “Can’t they even lock us up seriously?””

Domenico Losurdo, David Ferreira (2020). Stalin: The History and Critique of a Black Legend: 'The Complex and Contradictory Course of the Stalin Era; A Concentrationary Universe Full of Contradictions' (p. 128). [LG] - ↑ 3.0 3.1 Ludo Martens (1996). Another View of Stalin: 'The Great Purge' (p. 169). [PDF] Editions EPO. ISBN 9782872620814

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Central Intelligence Agency (1957). Four reports covering various aspects of forced labor in the USSR from 1945 to 1955.

- ↑ “pp. 2-6”

CIA (1957). "Forced Labor Camps in the USSR: Transfer of Prisoners between Camps" CIA. Archived from the original. - ↑ “Until 1952, the prisoners were given a guaranteed amount food, plus extra food for over-fulfillment of quotas.

From 1952 onward, the Gulag system operated upon “economic accountability” such that the more the prisoners worked, the more they were paid.

For over-fulfilling the norms by 105%, one day of sentence was counted as two, thus reducing the time spent in the Gulag by one day.

Furthermore, because of the socialist reconstruction post-war, the Soviet government had more funds and so they increased prisoners’ food supplies.

Until 1954, the prisoners worked 10 hours per day, whereas the free workers worked 8 hours per day. From 1954 onward, both prisoners and free workers worked 8 hours per day.

A CIA study of a sample camp showed that 95% of the prisoners were actual criminals.

In 1953, amnesty was given to 70% of the “ordinary criminals” of a sample camp studied by the CIA. Within the next 3 months, most of them were re-arrested for committing new crimes.”

Saed Teymuri (2018). "The Truth about the Soviet Gulag – Surprisingly Revealed by the CIA" Greanville Post. Archived from the original. - ↑ “We find that even in the Gulag, where force could be most conveniently applied, camp administrators combined material incentives with overt coercion, and, as time passed, they placed more weight on motivation. By the time the Gulag system was abandoned as a major instrument of Soviet industrial policy, the primary distinction between slave and free labor had been blurred: Gulag inmates were being paid wages according to a system that mirrored that of the civilian economy described by Bergson…

The Gulag administration [also] used a “work credit” system, whereby sentences were reduced (by two days or more for every day the norm was overfulfilled).”

L. Borodkin & S. Ertz (2003). Compensation Versus Coercion in the Soviet GULAG. [PDF] - ↑ “The prisoners were allowed free run of the prison. They organized morning gymnastic

sessions, founded an orchestra and a chorus, created a “club” supplied with foreign journals and a good library. According to tradition―dating back to pre-revolutionary days―every prisoner left behind his books after he was freed. A prisoners’ council assigned everyone cells, some of which were beautifully supplied with carpets on the floors and walls. Another prisoner remembered that “we strolled along the corridors as if they were boulevards.” To Babina, prison life seemed unreal: “Can’t they even lock us up seriously?””

Domenico Losurdo, David Ferreira (2020). Stalin: The History and Critique of a Black Legend: 'The Complex and Contradictory Course of the Stalin Era; A Concentrationary Universe Full of Contradictions' (p. 128). [LG] - ↑ 9.0 9.1 "Forced Labor Camps in the USSR" (1957-02-11). Central Intelligence Agency. Archived from the original on 2023-03-28. Retrieved 2023-07-01.

- ↑ Anatoly Vishnevsky (2006). The Demographic Modernization of Russia, 1900-2000 (p. 432). Moscow. ISBN 5983790420

- ↑ “Unburdened by any documentation, these “estimates” invite us to conclude that the sum total of people incarcerated in the labor camps over a twenty-two year period (allowing for turnovers due to death and term expirations) would have constituted an astonishing portion of the Soviet population. The support and supervision of the gulag (all the labor camps, labor colonies, and prisons of the Soviet system) would have been the USSR’s single largest enterprise.

In 1993, for the first time, several historians gained access to previously secret Soviet police archives and were able to establish well-documented estimates of prison and labor camp populations. They found that the total population of the entire gulag as of January 1939, near the end of the Great Purges, was 2,022,976. …

Soviet labor camps were not death camps like those the N@zis built across Europe. There was no systematic extermination of inmates, no gas chambers or crematoria to dispose of millions of bodies. Despite harsh conditions, the great majority of gulag inmates survived and eventually returned to society when granted amnesty or when their terms were finished. In any given year, 20 to 40 percent of the inmates were released, according to archive records. Oblivious to these facts, the Moscow correspondent of the New York Times (7/31/96) continues to describe the gulag as “the largest system of death camps in modern history.” …

Most of those incarcerated in the gulag were not political prisoners, and the same appears to be true of inmates in the other communist states…”

Michael Parenti (1997). Blackshirts and Reds: Rational Fascism and the Overthrow of Communism. PDF. - ↑ Saed Teymuri (2018-10-31). The Truth about the Soviet Gulag - Surprisingly Revealed by the CIA The Stalinist Katyusha. Archived from the original on 2019-04-01. Retrieved 2022-09-11.

- ↑ “He was Solzhenytsin before Solzhenytsin, in the phrase of Timothy Garton Ash. The Great Terror came out in 1968, four years before the first volume of The Gulag Archipelago, and it became, Garton Ash says, “a fixture in the political imagination of anybody thinking about communism”. ... He took a job in the Foreign Office's fairly secret Information Research Department, dedicated to combatting Soviet propaganda, and increasingly pursuing an anti-communist agenda of its own, fostering relationships with journalists, trade unions and other organisations.

It was for the IRD that George Orwell supplied a list of literary figures whom he thought might serve a communist government. Patricia Brown, who worked there at the same time, remembers Conquest as a brilliant, arrogant figure. He remains proud of the fact that when he arrived, he had 10 people reporting to him; by the time he left he had got rid of responsibility for all of them and needed to worry about nobody's work but his own.

He was clearly marked out as a high-flyer. The Foreign Office not only overlooked his first divorce, they sent him to the UN Security Council, where he was part of the British delegation for a while. In 1956 he left the IRD and went freelance, partly because Tatiana developed schizophrenia and they broke up: "It finally became impossible: she was extremely nice and charming, very very pretty; but she had this frightful thing."”

Andrew Brown (2003-02-15). "Scourge and poet" The Guardian. Archived from the original. - ↑ "Solzhenitsyn's Ex‐Wife Says ‘Gulag’ Is ‘Folklore’" (1974-02-06). New York Times.

- ↑ Robert Service (2003-06-07). "The accountancy of pain" The Guardian. Archived from the original.

- ↑ “Anne E. Applebaum, Staff Writer, The Atlantic (speaking virtually)”

Council on Foreign Relations (2024-05-07). "Guarding the Ballot: Addressing Foreign Disinformation and Election Interference" cfr.org. Archived from the original. - ↑ “Wilson also recognized the enormous contributions of departing Board members: Congressman David Skaggs and Marlene Colucci, who served on the Board for three terms, totaling nine years, as well as Anne Applebaum and Nadia Schadlow. “We are grateful to our departing Board members who helped NED sharpen its strategy and execution, as a unique asset for our nation effectively supporting freedom around the world,” said Wilson. “Their expertise and leadership on the Board will be missed.””

National Endowment for Democracy (2025-01-17). "NED Board Elects New Chairman and Members" ned.org. Archived from the original.