More languages

More actions

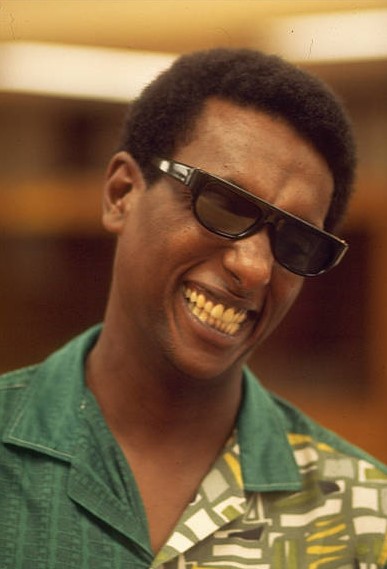

Kwame Ture | |

|---|---|

Portrait of Kwame Ture | |

| Born | Stokely Carmichael June 29, 1941 Port of Spain, British Trinidad and Tobago |

| Died | November 15, 1998 (Age 57) Conakry, Guinea |

| Cause of death | Prostate Cancer |

| Nationality | Guinean |

| Political orientation | Communsim Nkrumahism (developed what is now known as Nkrumahism-Toureism-Cabralism) Scientific Socialism Pan-Africanism |

| Political party | Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee Black Panther Party Democratic Party of Guinea - African Democratic Rally All-African People's Revolutionary Party |

Kwame Ture, born Stokely Carmichael, was a prominent civil rights organizer and founder of the Black Power movement. After studying Marxist theory in high school, Ture would go on to embrace political activism throughout his years in Howard University. During those years, he was introduced to the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, which despite being founded on the belief that racism and aparthied could be ended through nonviolence, the influences and later the leaderships of Kwame Ture and H. Rap Brown would lead the organization into becoming a hotbed for Black Power ideology. While leading SNCC, Kwame Ture led an ideological shift which resulted in the expulsion of white members from the organization, denunciation of Zionism and capitalism and calls for Black Power as a means to counteract white supremacy. After taking up Nkrumah's offer while in Conakry, Kwame Ture moved to Guinea, where he befriended Co-Presidents Sekou Touré and Kwame Nkrumah and lived with his wife, Mariam Makeba. The purpose of him moving was to build the All-African People's Revolutionary Party and carry out a continental war of people's liberation.[1]

Biography

Early life

On June 29th, 1941; Stokely Carmichael was born in his father's house in the city of Port of Spain, Trinidad and Tobago. His father, Adolphus Carmichael, was a carpenter[2] and had built the house in which he and his family resided in.[3] In 1944 his mother, Mabel Carmichael, who was born in the US Panama Canal Zone,[4] moved to the United States due to tensions with her in-laws.[5] Two years later his father would join her in Harlem,[6] leaving Stokely to be raised by his grandmother and aunts for 6 years.[7]

At 11 years old, Stokely and his siblings then moved to his parents to New York; where the Carmichaels lived as one of the few Africans in a predominantly white community in the Bronx populated by Italian, Irish and Jewish folk.[8] His father was able to purchase the home in the white community due to it being cramped and ugly, making it undesirable for most buyers.[9][10] Because of the building's state, Adolphus Carmichael worked tirelessly to renovate and improve the house,[11] thus gaining respect from the locals.[12] After being integrated with the locals, Stokely engaged in petty theft due to peer pressure from his friends[13], but later left the Morris Park Dukes street gang after they started producing zip guns.[14]

Carmichael was later enrolled at the Bronx High School of Science, an elite predominantly white school in his area. While in high school, Stokely consistently excelled beyond his peers despite their affluent backgrounds and become an exotic attraction to white observers die to his race and high intelligence. During these years, Stokely became good friends with Gene Dennis, a member of the Young Communist League (YCL) and son of Communist Party USA member Eugene Dennis. This friendship introduced the young Carmichael to a series of YCL meetings and study sessions. His introduction to Marxism also heightened his interest in politics, which over time made him familiar to names like Marx, Engels, Lenin and Trotsky. Despite this, he didn't join any Marxist organizations nor adopted Marxism due to his religiosity and felt doing so would alienate him from the black community. When attending a communist meeting with Gene and other students from Science, Stokely was introduced to Bayard Rustin; who's performance commanded his attention as it was a rare moment of a meaningful black presence in communist circles. Although he did meet black members of communist leadership at Gene's house, Stokely considered them distant unlike Rustin. Carmichael's impression of Rustin led him to turn to authors C. L. R. James and George Padmore. As he read both enthusiastically, Stokely noticed the contrast on their reception among white Marxists and black nationalists on 125th Street. On the rare occasions when Padmore and James were brought up, members of the Young Communists were dismissive of both; dismissing Padmore for "abandoning communism" and outing James as a Trotskyite. The nationalists on 125th street however praised both as African revolutionaries and promoted their works. Carmichael also contrasted the rhetoric the Young Communists espoused in support of labor unions with discussions with his father and his friends about their treatment by labor unions and white workers at their jobs.

His junior and senior years saw his political life grew more active when presented with the popularity and successes of Dr. King's nonviolent movement in Alabama. Due to King managing to rake in support among white moderates to combat Jim Crow, Stokely respected King and became an avid supporter. The 125th street nationalists however were critical of King's nonviolence and mocked his movement, prompting him to disassociate with them. He and a group of Science student activists often attended peace rallies called by the Ban the Bomb movement while supporting CORE demonstrations against segregation. Stokely also protested the Sharpsville massacre and helped Bayard Rustin organize one of his "Youth Marches for Integrated Schools," where he might have first heard King address a large group. While protesting against the Committee for Un-American activities with local communists, Carmichael continued noted the lack of Africans present, which he found typical of the socialists groups he was aware of. It was at the protest where he discovered an all black group associated with the D.C's Nonviolent Action Group (NAG). NAG was made up of mostly Howard University students, though it wasn't a recognized campus organization. The discovery prompted Stokely to join enthusiastically, as prior he felt isolated in predominantly white spaces.[1]

Howard University

Once graduating in 1960, Carmichael enrolled at Howard University where he would receive his degree in Philosophy. In NAG, he met H. Rap Brown, who would go on to become a heavily influential figure in the Black Power Movement. As a young adult in Howard, Stokely was introduced to the immense self-immolation of black identity that was omnipresent in campus, as well as the attempts to prevent African immigrants from interacting with Afro-Americans. The latter was brought to his attention during the school's orientation for foreigners, in which administrators warned them not to interact with "American Negros" on the basis of cultural differences and community violence. In another instance, his girlfriend was threatened with expulsion for wearing her natural hair.[1]

SNCC

In the aftermath of the Greensboro sit-ins, a nation-wide trend of social activism began to take place. Initially, Stokely didn't think much of it given it was a minor case of African-Americans sitting at a segregated area. Soon afterwards, however, sit-ins began to take place across the Black Belt before spreading across the rest of the United States four months later. The rise in public disobedience and participation in the civil rights movement then led to Ella Baker founding the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) two months later with the help of Dr. King and his Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). Despite King's intention of creating a youth wing subordinate to the SCLC, Ms. Baker envisioned an independent student movement and refused to be apart of any arrangement that would lead to the coopting of the student movement by Dr. King and his ministers of the SCLC, prompting her to walk out of the student conference that created SNCC.[1]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Ready For Revolution: The Life and Struggles of Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture)

- ↑ “Among his varied talents, the late Adolphus Carmichael was by profession a master carpenter”

Kwame Ture (2003). Ready For Revolution: The Life and Struggles of Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture): 'Oriki: Ancestors and Roots' (pp. 12-13). [PDF] - ↑ “I was born in the house my father built for his family at 54 Oxford Street at the bottom of the forty-two steps in the city of Port of Spain, Trinidad”

Kwame Ture (2003). Ready For Revolution: The Life and Struggles of Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture): 'Oriki: Ancestors and Roots' (p. 12). [PDF] - ↑ “My mother's father, Mr. Joshua Charles, was born in Antigua. A colonial policeman, he had been posted to Montserrat, where he met my grandmother. He was then posted to Nevis, where, like thousands of Caribbean black men, he was forced by economic conditions to work in the building of the Panama Canal. Unlike most though, Grandfather Charles brought along his young bride, which is how my mother and all her siblings came to be born in the Canal Zone.”

Kwame Ture (2003). Ready For Revolution: The Life and Struggles of Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture): 'Oriki: Ancestors and Roots' (p. 15). [PDF] - ↑ “So in October of 1944, leaving husband, young children, and the ultimatum "You will have to choose," behind her, Mabel Florence Charles Carmichael, aged twenty-three and looking much younger, set out for God's Country. Not in search of a "better" life or the American Dream, but in impulsive flight and as a personal declaration of independence from domineering in-laws.”

Kwame Ture (2003). Ready for the Revolution: 'Oriki: Ancestors and Roots' (pp. 20-21). [PDF] - ↑ “So in June of 1946, the otherwise utterly law-abiding Adolphus Carmichael signed on as an able seaman on a northbound freighter, jumped ship in New York harbor, and reunited with his wife. My sister was four, I almost five, and Lynette an infant. We were not to see either parent again until I was almost eleven.”

Kwame Ture (2003). Ready For Revolution: The Life and Struggles of Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture): 'Oriki: Ancestors and Roots' (p. 21). - ↑ “This, then, was the family of my childhood, my grandma, her three adult daughters, and the four children. [...] All the aunts worked while Grandma was responsible for the children during the day. Tante Elaine, Austin's mom, was a teacher at Mr. Young's private school. She brought to the household a rigorous attention to order, detail, and duty. She also brought home her reverence for education and the strict administration of discipline, which were projections of the classroom persona of all colonial schoolteachers of the time. Mummy Olga, more fun-loving and easygoing, worked in a department store, where dealing with the public was an occupation well suited to her outgoing, friendly nature.”

Kwame Ture (2003). Ready For Revolution: The Life and Struggles of Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture): 'The House at the Forty-Two Steps' (p. 23). [PDF] - ↑ “The house was farther up in the Bronx, on Amethyst Street, in the Morris Park/White Plains Road area, not far from the Bronx Zoo. We would discover that the neighborhood was heavily Italian with a strong admixture of Irish. It was respectable working class, "ethnic, and very, very Catholic. On one side it bordered Pelham Parkway, across which was a predominantly Jewish enclave. Ours would be the first, and for much of my youth, the only African family in that immediate neighborhood.”

Kwame Ture (2003). Ready for Revolution: The Life and Struggles of Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture): 'A Better Neighborhood' (p. 60). [PDF] - ↑ “It was a dump. I mean, it was a serious, serious dump. In fact, it was the local eyesore, and the reason-I now understand clearly-my father had been able to get the house with no visible opposition was because it was, hands down, the worst house on the block. It was so run-down, beat-up, and ill kept that no one wanted it. If that house were a horse, it would have been described as "hard rode and put up wet." A creature in dire need of a little care and nurturing. My dad was the "sucker" the owners had "seen coming" on whom to unload their white elephant. Which is one reason, I'm sure, the race question was overlooked. Who else could have been expected to buy such a wreck?”

Kwame Ture (2003). Ready For Revolution: The Life and Struggles of Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture): 'A Better Neighborhood' (p. 61). [PDF] - ↑ “When we first saw it, we children were shocked. We looked around the house and at each other. I mean, even the cramped quarters at Stebbins looked like a mansion compared to what we were moving into. I mean, small, little, squinched-up rooms, dark, sunless interiors, filthy baseboards, a total mess and not at all inviting.”

Kwame Ture (2003). Ready for Revolution: The Life and Struggles of Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture): 'A Better Neighborhood' (p. 61). [PDF] - ↑ “Immediately when we moved in-my mother used to tease him fondly that he unpacked his tools before he unpacked his bed-my father set to work, even though it was January and cold. The remake took a long time, continuing in some way as long as he lived there. On those happy days when he had a construction job, my father worked on our house at night. On those all too many days when the union hiring hall failed to refer him to a job, he worked on our home day and night. Before he was through he had added rooms upstairs and down, knocked out walls to create more space, put in windows and doors. In a word, he completely transformed that wreck.”

Kwame Ture (2003). Ready for Revolution: The Life and Struggles of Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture): 'A Better Neighborhood' (p. 61). [PDF] - ↑ “We learned later that as the neighbors looked on, amusement turned to skepticism, skepticism to wonder, and wonder to respect. They were, after all, working men and respected industry and competence.”

Kwame Ture (2003). Ready for Revolution: The Life and Struggles of Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture): 'A Better Neighborhood' (p. 61). [PDF] - ↑ “Until that one night when I was hanging out and Paulie proposed that we rip off a store. And as he did so, he seemed to be looking straight at me. It was a test of some sort, that was clear. I had to calculate rather quickly. I understood clearly the stupidity of this act, but there was the pressure to belong. It was very much "All right, are you down with us or not?" Very much as if, you punk out now and you won't be able to hang no more. We'll know who you are. That kind of pressure.”

Kwame Ture (2003). Ready for Revolution: The Life and Struggles of Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture): 'A Better Neighborhood' (p. 66). [PDF] - ↑ “When the zips were made, some actually fired, most didn't. I can't now remember whether mine did. But this was the final act in my flirtation with the destructive behavior of our wanna-be gang. Now that we had guns that fired-at least a few did-were we really going to shoot, possibly maim or even kill, some kid we didn't even know? I am sure the Dukes never did, but I sure wasn't about to tag along to find out.”

Kwame Ture (2003). Ready for Revolution: The Life and Struggles of Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture): 'A Better Neighborhood' (p. 70). [PDF]