More languages

More actions

| Holy Roman Empire Heiliges Römisches Reich Sacrum Imperium Romanum | |

|---|---|

| 800/962–1806 | |

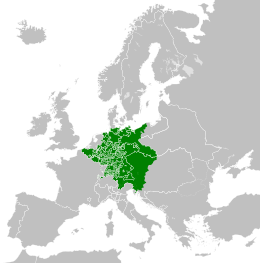

The empire in 1789 | |

| Common languages | German Latin |

| Dominant mode of production | Feudalism |

| Government | Monarchy |

| Population | |

• 1800 estimate | 29,000,000 |

The Holy Roman Empire (German: Heiliges Römisches Reich) was a political entity in Central Europe during the medieval and early modern periods. Its power base was in Austria, but it extended across what is now Germany, Czechia, Hungary, and northern Italy. It was deeply divided and had internal conflicts between the Emperor and local princes.[1]

History

The formation of the Holy Roman Empire began with Charlemagne's coronation as "Emperor of the Romans" in 800 and was solidified when Otto I was crowned emperor in 962 by Pope John XII. This effort aimed to revive the Western Roman Empire, which had seen its legal and political structure collapse during the 5th and 6th centuries, leaving the Roman imperial office vacant after the deposition of Romulus Augustulus in 476. In 797, Irene removed Byzantine Emperor Constantine VI from the throne, declaring herself Empress. Given that the Latin Church only recognized a male Roman Emperor as the head of Christendom, Pope Leo III sought a new candidate by creating the Holy Roman Empire.

The Czech population revolted in 1415 after the execution of the radical preacher Jan Hus. The rebellion included egalitarian Taborites who called for the elimination of exploitation and destruction of the feudal ruling class.

Under the rule of the Hapsburg dynasty, the Holy Roman Empire fought with Spain against France from 1494 and 1559 in northern Italy.[2]

Protestant Reformation

The Protestant Reformation began in what is now Germany in 1517. The Holy Roman Emperor summoned Martin Luther to the Diet of Worms in 1521 and threatened to execute him, but his teachings soon spread across the empire to two-thirds of German villages. Impoverished knights in southern Germany revolted from 1522 to 1523 followed by a peasant rebellion from 1524 to 1525 that threatened the entire feudal mode of production. Many German princes who opposed the Pope and Holy Roman Emperor converted to Protestantism.[1]

Thirty Years' War

In the early 17th century, Spain launched a feudal counterrevolution against the Reformation. Anti-Catholic nobles in Bohemia threw three imperial officials out of a window in Prague in 1618 and then refused to recognize the new Catholic emperor Ferdinand, granting the crown of Bohemia to a German Protestant prince named Frederick of Palatine. Catholic forces defeated Frederick in 1620 and restored the Catholic imperial government. The Netherlands, Denmark, Sweden, and France intervened against Spain, defeating the Hapsburgs in 1648. The population reduced the German population by half between 1618 and 1648 and drained Spain's resources, allowing France to surpass it in military power.[1]

Economy

Urban commodity production grew in the 14th and 15th centuries. Weaving was the most important industry, but goldsmithing, silversmithing, and wood engraving also existed for the benefit of the nobility. Commerce grew along with industry, and the Hanseatic League held a monopoly on sea trade for 100 years before falling to English and Dutch competition.

Agriculture lagged behind England and the Netherlands, and industry was behind Italy, Belgium, and England.[3]

Class system

Clergy

The printing press ended the clergy's monopoly over writing. The aristocratic section of the clergy, including bishops and archbishops, were either princes or the vassals of princes and brutally exploited the serfs. There were also poor preachers who did not benefit from feudalism and sympathized with the peasantry and urban masses.[3]

Nobility

The upper nobility was the princes who could declare war, organize local councils, and levy taxes without permission from the emperor. By 1600, most of the knights had become princes or lower nobles as the invention of guns made them unnecessary. Many knights owed money to the clergy and sought to become independent from their lords.[3]

Burghers

The urban middle class, the ancestors of modern bourgeois liberals, controlled the guilds and wanted more legislative power. It criticized the urban aristocracy (patricians) for favorite elite families that had been rich for centuries.[3]

Plebeians

The plebeians (future proletariat) were urban dwellers that had no citizenship rights. They included lumpenproletarians, day workers, and skilled journeymen. Some were former guild members while others were peasants.[3]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Neil Faulkner (2013). A Marxist History of the World: From Neanderthals to Neoliberals: 'The First Wave of Bourgeois Revolutions' (pp. 94–103). [PDF] Pluto Press. ISBN 9781849648639 [LG]

- ↑ Neil Faulkner (2013). A Marxist History of the World: From Neanderthals to Neoliberals: 'European Feudalism' (p. 88). [PDF] Pluto Press. ISBN 9781849648639 [LG]

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Friedrich Engels (1850). The Peasant War in Germany: 'The Economic Situation and Social Classes in Germany'. [MIA]