Provisional Military Government of Socialist Ethiopia (1974–1987)

More languages

More actions

| Provisional Military Government of Socialist Ethiopia የኅብረተሰብአዊት ኢትዮጵያ ጊዜያዊ ወታደራዊ መንግሥት | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1974–1987 | |||||||||

Anthem: ኢትዮጵያ ኢትዮጵያ ኢትዮጵያ ቅደሚ (English: Ethiopia, Ethiopia, Ethiopia be first" | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Capital and largest city | Addis Ababa | ||||||||

| Official languages | Amharic | ||||||||

| Dominant mode of production | Socialism | ||||||||

| Government | Marxist–Leninist military junta | ||||||||

• Head of State (15 September 1974 – 17 November 1974) | Aman Mikael Andom | ||||||||

• Head of State (17 November 1974 – 28 November 1974) | Mengistu Haile Mariam | ||||||||

• Head of State (28 November 1974 – 3 February 1977) | Tafari Benti | ||||||||

• Head of State (3 February 1977 – 10 September 1987) | Mengistu Haile Mariam | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

• Established | 1974 | ||||||||

• Dissolution | 1987 | ||||||||

| Area | |||||||||

• Total | 1,221,900 km² | ||||||||

| Population | |||||||||

• 1987 estimate | 46,706,229 | ||||||||

| Currency | Birr | ||||||||

| |||||||||

The Provisional Military Administrative Council of Socialist Ethiopia (PMAC, Amharic: የኅብረተሰብአዊት ኢትዮጵያ ጊዜያዊ ወታደራዊ መንግሥት) also known as the Derg (sometimes transliterated Dirg or Dergue, Ge'ez: ደርግ, meaning "committee" or "council"), was a socialist military junta that ruled Ethiopia between the Ethiopian revolution of 1974 and the establishment of a civilian government in 1987.

The Derg was established in June 1974 as the Coordinating Committee of the Armed Forces, Police and Territorial Army, by officers of the Ethiopian Army and Police led initially by chairman Mengistu Haile Mariam. On 12 September 1974, the Derg overthrew the government of the Ethiopian Empire and Emperor Haile Selassie during the Ethiopian revolution, and three days later formally renamed itself the Provisional Military Administrative Council.

History

Revolution

See main article: Ethiopian revolution

It began on the 12 January 1974, when Ethiopian soldiers began a rebellion in Negele Borana, with the protests continuing into February 1974. People from different occupations, starting from junior army officers, students and teachers, and taxi drivers joined a strike to demand human rights, social change, agrarian reforms, price controls, free schooling, and releasing political prisoners, and labor unions demanded a fixation of wages in accordance with price indexes, as well as pensions for workers, etc.

In June 1974, a group of army officers established the Coordinating Committee of the Armed Forces, later branding itself as the Derg, which aimed to topple Haile Selassie cabinet under Prime Minister Endelkachew Makonnen. By September of that year, the Derg began detaining Endalkachew's closest advisors, dissolved the Crown Council and Imperial Court and disbanded the emperor's military staff. The Ethiopian Revolution ended with the 12 September coup d'état of Haile Selassie by the Coordinating Committee of the Armed Forces.

In September 1974, the absolute monarchy of Ethiopia led by Emperor Haile Selassie was overthrown.

Early History, Power struggles and Consolidation

Opposition to the Derg

Nej Shibir and Qey Shibir (White Terror and Red Terror)

Ogaden-War (1977-1978)

Background

Course of the War

Views of the Opposition to the Derg

Effects

Emergence of Ethnonationalist Groups and the Ethiopian Civil War

Formation of the Workers Party of Ethiopia

Famine of 1984-1986

Dissolution of the Derg

Nationalisation, Land Reform and the Zemecha Campaign

First Policy Formulations

The Derg issued its ten-point-programme on the 20th December 1974, which was its first written attempt to formulate policy:

- Ethiopia shall remain a united country, without ethnic, religious, linguistic and cultural differences.

- Ethiopia wishes to see the setting up of an economic, cultural and social community with Kenya, Sudan and Somalia.

- The slogan Ityopya Tikdem (Amharic: ኢትዮጵያ ትቅደም for "Ethiopia first" or sometimes translated "Ethiopia forward", sometimes in its more complete Yaleminim dem, Ityopya Tikdem, Amharic for "Without (shedding) Blood, Ethiopia first" or later ) of the Ethiopian revolution is to be based on a specifically Ethiopian socialism.

- Every regional administration and every village shall manage its own resources and be self-sufficient .

- A great political party based on the revolutionary philosophy of Ityopya Tikdem shall be constituted on a nationalist and socialist basis.

- The entire economy shall be in the hands of the state. All assets existing in Ethiopia are by right the property of the Ethiopian people. Only a limited number of businesses will remain private if they are deemedto be of public utility.

- The right to own land shall be restricted to those who work the land.

- Industry will be managed by the state. Some private enterprises deemed to be of public utility will be left in private hands until the state considers it preferable to nationalize them.

- The family, which will be the fundamental basis of Ethiopian society, will be protected against all foreign influences, vices and defects.

- Ethiopia's existing foreign policy will be essentially maintained. The new regime will however endeavour to strengthen good-neighbourly relations with all neighbouring countries.[1]

This was the primary formulation of the political program of the Derg until the Programme of the National Democratic Revolution in 1976.[1] The shortcomings and problems with this early policy formulation are described by Christopher Clapham as follows:

"The first article, in simply denying the existence of ethnic and related differences, obscured the conflict between an assimilationist nationalism (in which differences would be abolished) and the recognition of separate 'nationalities' on an equal basis, which would underlie the whole problem of national integration. The conservative provisions on foreign policy were to prove incompatible with the international implications of revolution, while in the management of the economy, the emphasis on the state was at odds with the references to regional autonomy and the idea of land to the tiller. In the event, neither of these last two principles was implemented , while the party , with which many of these contradictions were bound up, did not come into existence for a further ten years."[1]

National Democratic Revolution Programme

In April 1976, the Derg released the National Democratic Revolution Program, which included land reform, nationalization of industries, and reorganization of unions.[2]

The PMAC’s policy towards the nationalities in Ethiopia is theoretically committed to regional autonomy, as outlined in the National Democratic Revolution Program:

"Given Ethiopia’s existing situation, the problem of nationalities can be resolved if each nationality is accorded full right to self-government. This means that each nationality will have regional autonomy to decide on matters concerning its internal affairs. Within its environs, it has the right to determine the contents of its political, economic and social life, use its own language and elect its own leaders and administrators to head its internal organs. This right of self-government of nationalities will be implemented in accordance with all democratic procedures and principles."[2]

Nationalisation

On January 1, 1975 all banks and thirteen insurance companies were nationalized. On February 3 seventy-two industrial and commercial companies were fully nationalized, and the state assumed majority control in twenty-nine others. By late 1976 two-thirds of all manufacturing was under the control of the Ministry of Industry.[3]

A Declaration on the Economic Policy of Socialist Ethiopia, issued on 7 February, laid down areas of the economy reserved for government, for joint ventures between government and private capital (in such areas as mining and tourism), and for private ownership.[1]

The banks that were nationalized consisted of the Commercial Bank of the Addis Ababa Share Company, the Banco di Roma Share Company and the Banco di Napoli Share Company, They were brought under the administration of the Ethiopian Central Bank in addition to the three already in state hands prior to 1974. A later legislation merged the nationalized banks under the administration of one bank (the Addis Ababa Bank).[4]

Towards the end of 1974, the Derg established a economic policy formulation committee led by Captain Moges Welde-Michael and Aircraftsman Gesese Welde-Kidan (first and vice chairman of the Derg Economic Sub-committee respectively) and had the following as its members: Mebrate Mengistu (Minister of Natural Resources Development), Mohammed Abdurahmin (Minister of Commerce, Industry and Tourism), Tadese Moges (Minister of state in the Ministry of commerce, Industry and Tourism), Dr. Debebe Worku (expert in the Ministry of Commerce, Trade and Tourism), Tekalign Gedamu (Minister of Transport and Communications), Col. Belachew Jemaneh (Minister of Interior), Tefera Degefe (Governor of the National Bank of Ethiopia), Birihanu Wakoya (Commissioner of the Ethiopian Planning Board), Ashagre Yigletu and Wole Chekol (representatives of the Provisional National Advisory Commission). The organizations were deemed nationalized by the Derg as of February 7, 1975.[4]

Also, the broad outlines of the principles in accordance with which mining, industrial and commercial organizations were to be nationalized was enacted on the same day as "The Government Ownership of the Means of Production Proclamation 26, 1975". That law delineates between three kinds of mining, industrial and commercial activities: The first were to be owned and operated by the government exclusively, the second to be owned and operated by government and private investors jointly, and the third to be owned and operated by private investors exclusively. The preamble to the legislation explained that the activities under the first category are brought under state control because it was necessary to give precedence to public interest. Those under the second category were opened to joint venture because they were not amenable to complete government ownership; and those in the third category were left to the private sector because doing so would not be harmful to society. It was further explained that the basis for the delineation between the three categories was Ethiopian Socialism. If any of the economic activities under the first category were in private hands, they were to be nationalized. [4]

It was in accordance with this principle that the Economic Policy Committee mentioned above short listed a total of 72 business organisations for nationalization by the Derg. The undertakings so nationalized were: thirteen food-processing industries, nine leather-processing and shoe-making industries, four printing establishments, eight chemical-processing facilities, five metal factories, and eleven others that are not fully classified. No mining activities were nationalized because they were almost non-existent and the very few that existed were, in any case, owned and run by the state. Further, it was provided that the government was to hold a minimum of fifty-one per cent of the shares in each of the joint ventures.[4]

The private sector was further delimited by another piece of legislation which was enacted in December, 1975. According to it, retailers were allowed to a maximum capital of about a hundred thousand US Dollars, wholesalers about a hundred and fifty thousand US Dollars, and industrialists about two hundred and fifty thousand US Dollars. Five exceptions were made to these capital restrictions: business organizations which were already in private hands; construction works, surface transport, inland water transport and the publication of newspapers and magazines to be undertaken in the future, wholesalers to be engaged in the sale of agricultural products, skins and hidesand retailers to be engaged in import-export businesses; and those who secure a waiver from the Ministry of Commerce and Industry.[4]

Urban Reform (1975-1976)

On July 26, 1975 the PMAC issued Proclamation No. 47 of 1975, the "Government ownership of Urban Lands and Extra Houses Proclamation".[5]

The twelve-point preamble to Proclamation No. 47 sets forth a number of reasons and goals for the measures announced in the law. A handful of urban landlords are held to have obstructed urban planning, development, and improvement in urban living conditions through land speculation and abuses of economic and political power as well as exploiting tenants and evading taxation. Finally, the preamble maintains that nationalization of urban land and houses is essential for careful planning and resource utilization, the extension of secure housing facilities to poor urban dwellers, and improved urban conditions. The preamble holds:

"(...) in order to bridge the wide gap in the standard of living of urban dwellers by appropriate allocation of disproportionately-held wealth and income as well as the inequitable provision of services among urban dwellers and to eliminate the exploitation of the many by the few, it is necessary to bring under Government ownership and control urban lands and extra urban houses."[5]

The most important provision of the legislation declared that, as of its effective date (August, 7, 1975), all urban land and extra houses would become the property of the government. It provided that the government would pay compensation for the nationalized extra houses but not for land.[4]

More than 200 communities possessed township and municipal status in 1975. Article 3 nationalized, without compensation, all land within the boundaries of these townships and municipalities. Moreover, Article 6(1) abolished tenancy and freed former tenants from rent payments, debts, and other obligations owed to landlords. In place of private ownership, persons and families may be granted possessory rights over a maximum of 500 square meters of urban land under Article 5(1). This article allows the spouse or children of the holder to inherit possession of urban land: however, Article 4(1) prohibits the holder from transferring the usufruct by sale, antichresis, or mortgage. All urban tenants, including persons who previously did not own their dwelling units, are authorized by Article 6(2) and 7(1) to claim possessory rights over up to 500 square meters of the land they occupied on the date of the proclamation.[5]

Individuals or families are permitted by Article 11(1) to own one house, in only one township or municipality, as living quarters. 76 Article 13(1) transferred any additional or "extra" urban houses belonging to an individual or family on July 26, 1975, as well as all multiple-family dwellings, to government ownership. Persons, families and organizations owning such units were required by Article 13(2) to surrender them to the government within 30 days of the proclamation's effective date. Exceptions to these rules are provided in Article 11, which allows an organization to own multiple units for the purpose of housing its employees, and provides that persons, families, or organizations may own more than one business unit upon approval by the government.[5]

Urban Dweller's Association

The nationalized extra houses were rented out to urban dwellers at rates fixed by the Ministry of Urban Development and Housing. Mostly, rents of up to 100 Birr (about 50 US dollars) were to be collected by urban dwellers' associations (UDA), sometimes also known as kebeles (in reference to the smallest administrative unit), and rents above that were to be collected by the Ministry. All rents were to be used for providing services to urban dwellers in accordance with government comprehensive urban development plans and directives. In other words, UDA's were meant to use the rent they collected for developmental and other matters coming under their jurisdiction: maintenance of rented houses, payment of salaries of UDA's employees, common services for their members like latrines, water supplies, roads, kindergartens and basic health facilities. The rent collected by the Ministry was to be used for projects at the level of the cities.[4]

All urban inhabitants were made members of UDA's except ex-landlords who were prohibited from voting in the election of UDA leaders or from being elected themselves for a year. The organs of UDA's at each level included an executive committee, a public welfare committee and a judicial tribunal. The first of these is established through direct election by all members and the other two are then established by the executive. The primary task of delineating the boundaries of and organizing the UDAs was entrusted to the Ministry of Urban Development and Housing.[4]

Hence, the Ministry divided the capital city, which then had a population of just over a million inhabitants, into three hundred kebeles (districts). The city's elections were held on August 24, 1975, The size of each of the committees and the establishment of control committees were decided by an organizing committee of the Ministry. The establishment of UDAs in the provincial towns and villages did not start until the second half of October. All these elections were concerned with the establishment of kebele UDAs; those of the higher and central UDAs were not held until the next round of general elections over a year later.[4]

The executive committees of UDAs are authorised to follow up land use and building; set up educational, health, market, road and similar services; collect land and house rent up to about fifty US dollars per piece of land or per house per month; and, spend the rent it collects and subsidy it receives on building economical houses and on improving the quality of life of its members.[4]

The task of protecting public property and the lives and welfare of the urban population at the local level is entrusted to the public welfare committees which were made accountable to the executive committees of UDAs. The public welfare committees were the equivalents of the defence committees of peasant associations; both later came to be known as "the revolution defence squads".[4]

The mandate of the kebele judicial tribunal is to hear and decide disputes between urban dwellers over land and houses that of the higher judicial tribunal, between kebele associations themselves and between kebele associations and urban dwellers and that of the central judicial tribunal, between higher associations. Unlike the judicial tribunals of peasant associations, those of UDAs were not given jurisdiction to preside over criminal offences at least at this stage.[4]

Land Reform (1975–1979)

The necessity for rural development is illustrated by the mentioning of some statistics of Ethiopia at the time: 92% of the people generate 60-65% of the GDP and 90% of the exports through agriculture. Subsistence peasant families constitute 86% of the population, and their production accounts for 45-50% of the GDP at the time.[6] Ethiopian agriculture prior to the Revolution was regarded by many to operate under its potential, given the countries large size, relatively low population density, general fertility, sufficient rainfall (at the time), climate and elevation variations allowing for cropping diversitification and 22.5 million peasants working only 7,9% of the total land. The 1973 famine in Wollo evidenced the previous governments disinterest in utilising that potential.[6] Additionally, less than 1% of the population owned more than 70% of the arable land. The royal family and landed aristocracy owned between 50-60% of arable land, leaving over 50% of the rural population as tenant-farmers.[7] The church is estimated to have possessed 20% of all arable land and 5% of all Ethiopian land, from which it derived most of its income.[8]

Against the advice of Chinese, Yugoslav and Soviet embassy officials, the Derg enacted far-reaching measures. No legal ownership of rural land was henceforth permitted: only a 'possessory' or 'usufructuary' form of tenancy was allowed. No employment of wage-labour by farmers was permitted on this land, which therefore had to be cultivated by family labour.[9]

The legal framework of the early land reform was provided by a series of decrees, or "proclamations" of the Provisional Military Administrative Council (PMAC) . These proclamations, issued between 4 March 1975 and June 1979, form a coherent whole.[10] Land reform was not conceived simply as a matter of breaking up large estates, but above all as the problem of creating a new political and social organization in the countryside to defeat the landlords and allow the peasants to control their land and their affairs.[10] These proclamations are, in order:

- Proclamation No.31 of 1975 ("A Proclamation to Provide for the Public Ownership of Rural Lands")

- Proclamation No. 71 of 1975 ("Peasant Associations Organization and Consolidation Proclamation.")

- Proclamation No. 77 of 1976. as amended by No. 152 of 1978: Rural Land Fee and Agricultural Activities Income Tax Proclamation[10]

- Proclamation No. 130. Sept. 1977 ("A Proclamation on Formation of nation-wide Peasant Associations")[11]

- Proclamation issued June 1979[9]: guideline of the formation of Agricultural Producers Cooperatives

- Proclamation No. 223/1982: Peasant Associations Consolidation

Proclamation No.31 reads in its preamble, proclaiming the wide- ranging effects and the reasoning for the proclamation:

"WHEREAS, in countries like Ethiopia where the economy is agricultural a person's right, honour, status and standard of living is determined by his relation to the land;(...) several thousand gashas of land have been grabbed from the masses by an insignificant number of feudal lords and their families as a result of which the Ethiopian masses have been forced to live under conditions of serfdom; (...) it is essential to fundamentally alter the existing agrarian relations so that the Ethiopian peasant masses which have paid so much in sweat as in blood to maintain an extravagant feudal class may be liberated from age-old feudal oppression, injustice, poverty, and disease, and in order to lay the basis upon which all Ethiopians may henceforth live in equality, freedom, and fraternity; (...) the development of Ethiopia of the future can be assured not by permitting the exploitation of the many by the few as is now the case, but only by instituting basic change in agrarian relations which would lay the basis upon which, through work by cooperation, the development of one becomes the development of all; (...) in order to increase agricultural production and to make the tiller the owner of the fruits of his labour, it is necessary to release the productive forces of the rural economy by liquidating the feudal system under which the nobility, aristocracy and a small number of other persons with adequate means of livelihood have prospered by the toil and sweat of the masses; (...) it is necessary to provide work for all rural people; it is necessary to distribute land, increase rural income, and thereby lay the basis for the expansion of industry and the growth of the economy by providing for the participation of the peasantry in the national market; (...) it is essential to abolish the feudal system in order to release for industry the human labour suppressed within such system; (..) it is necessary to narrow the gap in rural wealth and income" [12]

All land was declared the "collective property of the Ethiopian people." Landlords would receive no payment for their land (but there were promises to compensate for movable properties and permanent improvements previously made on the land)[13]. Any person willing to cultivate the land would be allotted the use of a plot, up to a maximum of ten hectares for each farming family. Private individuals would not be allowed to hire agricultural workers.[10]

To prevent the peasants from becoming de facto small-holders, each cultivating his fields in isolation from the others, Peasant Associations would be created throughout the country, each covering an area of at least eight hundred hectares. Membership in the associations was open to all farmers, except those who had previously owned more than ten hectares of land.[10]

These peasant associations were responsible for implementing the land reform and distributing the land equally among their members[10], considering both the size of the family and the quality of the soil. They were additionally empowered to supervise land-use regulations, administer public property, establish judicial committees, service co-operatives and an elementary form of producer's cooperatives, and promote socio-economic infrastructure and villigization programs.[13] They would elect their own officials and adjudicate disputes arising from the distribution of land among their members. [10]Within the peasant associations, the peasants elected a chairperson, secretary, a treasurer and two assistants by show of hands. A number of peasant associations permitted farmers to work the land they possessed, but provided land to landless peasants. Some were more radical and completed land distribution within two months.[13] However, 79.7% of the members of judicial committees were illiterate, and the position was sometimes regarded as nominal, whereas few peasant associations held internal regulations in written form. The responsibility for forming peasant associations rested with the Ministry of Agriculture and the Ministry of Interior.

The proclamation treated the pattern of transfer of land differently depending on three tenure types: the northern rist tenure, private ownership tenure (which was most affected by the Proclamation in the way illustrated above) and tenure in nomadic areas. In the north, the peasant associations were primarily tasked with organizing producers cooperatives, without forseeing the need for land distribution. In the nomadic regions, the peasant associations were tasked to induce the cooperative use of water and grazing rights. Nomadic people were entitled to possess their grazing lands, except those that were used for mining or large-scale national agricultural projects. Payments made by nomadic people to traditional elites (called balabat,[8] not to be confused with the mekwanint of equal status) were nullified.[13]

The first step in the direction of strengthening the autonomy of the peasant associations was Proclamation No. 71 of 1975, called "Peasant Associations Organization and Consolidation Proclamation."

This measure accomplished three tasks:

- it gave the peasant associations a legal personality;

- it outlined a path of growth for the peasant associations beyond land distribution, allowing them to create cooperatives and even to set up their own armed defense squads of peasant militias; and

- it strengthened the higher level peasant associations, integrating them into the regional administration through the creation of "Revolutionary Administration and Development Committees."[10]

This was intended to allow peasant associations to borrow collectively under the governments loan plan in order to purchase seed and fertilizers, or to become members of a cooperative, i.e. fostering the conditions away from individual exploitation of the land and towards agricultural communes. It also expanded the political roles of the peasant associations:

- to enable peasants to secure and safeguard their political, economic and social rights;

- to enable the peasantry to administer itself;

- to enable the peasantry to participate in the struggle against feudalism and imperialism by building its consciousness in line with Hebrettesebawinet (Ethiopian socialism);

- to establish cooperative societies, women's associations, peasant defense squads and any other associations that may be necessary for the fulfillment of its goals and aims;

- to enable the peasantry to work collectively and to speed up social development by improving the quality of the instruments of production and the level of productivity;

- to sue and be sued;

- to issue and implement its internal regulations in order to achieve its goals and aims.[10]

The people's militia is established by Articles 11-14 and charged with helping the Ministry of Interior's police to protect the property and crops of peasants. This task is initially intended to keep former landlords from attempting to claim crop shares, expropriated land or oxen, or farm implements. In addition, the militia is to help the police locate criminals, safeguard national resources and properties, respond to the defense needs of the government, and enforce the decisions of peasant association executive committees and courts.[14] It is important to note that the decision to arm the peasants needs to be seen in the context of the severe criticism the Derg was subjected to by other radicals for failing to do so. Sometimes, the arming of peasants was done out of the peasants or Zemecha-Campaigners own initiative prior to the proclamation, with the formation of "Red Guards" especially in southern Ethiopia. These then often went about disarming the landlords. [13] By 1977, 98.8% of peasant associations had a defense squad, with memberships between 6-25 peasants.[13]

The now formed peasant associations would be divided into two categories, referred to as "service cooperative societies" (consiting of at least two peasant associations) and "agricultural producers' cooperative societies", with the vision of a gradual transformation from service cooperatives to advanced producers cooperatives[13], a guideline for which was enacted in the Decree of 1979.[15]

The goals of the service cooperatives were strictly economic, namely to provide their members with extension services, loans, storage facilities, and marketing services. In addition they were to encourage savings, distribute basic consumer goods, and establish flour mills and small cottage industries. The agricultural producers' cooperatives, on the other hand, had above all political goals. They would assume control over the "instruments of production" of their members, and gradually assume ownership; they would "divide members into working groups to enable them to work collectively," and their officials would be drawn only from among poor and middle peasants. Among their main objectives was "to struggle for the gradual abolition of exploitation from the rural areas."[10]

Through the Elementary producers cooperatives 75% of land was to be owned collectively, though farm impliments and livestock could remain private, whereas income was to be devided "from each according to his ability to each according to his contribution", barring special reserves, funds for welfare costs etc. Peasant cooperatives had a executive committee and an auditing committee to oversee the executive committee and to report the financial status of a cooperative to the general assembly. [13] By 1978, 343 service and 21 producers cooperatives existed in Ethiopia (covering 9% of all Peasants Associations).[13]

The "Rural Land Fee and Agricultural Activities Income Tax Proclamation." of January 1976 established agricultural income tax. The law begins with a preamble declaring it the national duty of every peasant given land use rights and the opportunity to earn income to contribute part of his earnings to finance development programs adopted by the government for the benefit of the rural populace. The preamble specifically notes the need for programs in agricultural research and extension, road construction, communications facilities, and market improvement. Land use fees and agricultural income taxes are to be collected either by the peasant associations, by a person appointed by the Ministry of Finance, or by the local woreda tax office of that ministry.[8]

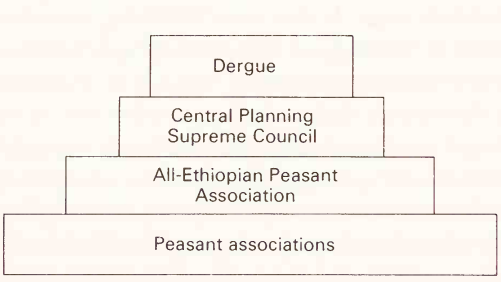

Since 1977 (Proclamation No.130), Peasant associations were to be organized into a five-level structure, with the lowest unit being the local peasant association and the highest governing body the All-Ethiopia Peasant Association (AEPA). Members of the AEPA are elected by the general assembles of the respective regional Peasants Associations.[11] In between, the woreda, awrajja and kifle-hagar peasant associations would coordinate local associations and set up judicial committees.[13] Furthermore, each peasant association would elect representatives to a woreda peasant association, and these in turn would elect their representatives to the awrajja peasant association.[10] Along with the organisation of Peasants Organisations the Organisations of Women's Organisations took place, within the structure of the Peasants Associations. On the 27th July, 1980, a Proclamation on the formation of Women's Associations on the national level was issued. Members were to be at least 15 years old.[15]

By late 1975, 19,000 peasant associations had been established, with a membership of about 4 million peasant households. In 1976, this reached 24,707 peasant associations with 6.8 million households, and in 1977-1978 there were 28,583 peasant associations with a membership of 7.3 million households.[13]

To shore up and organize the land reform more efficiently, the Derg in 1978 created the National Revolution Development Campaign and Central Planning Supreme Council which works with the AEPA (All Ethiopians Peasant Association) in order to overcome logistical and political impediments of the programme.[16] Agricultural output rose 2.4 per cent in 1978-9, and 4.8 per cent in 1979-80. [9]

The Derg enacted a new decree starting June 1979, which placed new upper limits on areas of tenancy and laid the basis for the transition to producers' cooperatives. The Proclamation divided the development of the Producers' Cooperative into three phases: initially the peasants were to form an elementary type of Cooperative (malba), and then gradually move towards an advanced Producers' Cooperative (welba) and finally reach the highest level, where the advanced Producers's Cooperatives would form a type of commune (weland).[15]

The malba stage could start with a small volunteer nucleus of at least three peasants, or, alternatively, members of a Peasants' Association might transform the Association into a Cooperative. Each member would be entitled to up to 2,000 msqaure meters of land varying within an association with the number of family members who joined the Cooperative. Each member was still to own farm implements and livestock, but would already contribute to the Cooperative in the form of capital. The income of individual members would be based on property income and the quantity and quality of labour contributed. The malba stage was intended to gradually transform itself to the advanced Producers' Cooperative welba, in which the contradictions between private ownership of a instruments of production and collective work would cease to exist. The members would either sell their farm implements and livestock, or voluntarily contribute them to the cooperative. Each member of the cooperative might hold land of up to 1000 square meters and raise livestock and garden crops on their private plots, if granted approval of the general assembly. Income distribution would be based on the labour contribution of the members.[15]

The final stage, known as weland, involves a kolkhoz-type structure: it abolishes private tenancy over land. These welands would include about 2,500 individual adult members, and would cover an area of around 4,000 hectares of land.[9]

By 1980 there were just thirty producer cooperatives in existence, mainly of the initial melba variety, and another 130 were under consideration.[15]

Limitations and Problems of the Land Reform and its Implementation

Peasants in the south were elated with the new programme and gave the Derg wholehearted support. In the north, however, where much of the land was held under ancient communal land-tenure systems, many peasants, particularly in Gojjam province, railed against the proclamation, which they viewed as a destruction of their traditional rights. (Land was held in common by descendants of the original person first granted usage rights and where title remained unfixed. Land, however, was individually farmed.) This opposition was merely a continuation of the political troubles in Gojjam caused by Haile Selassie in 1967. To the people of Gojjam land, not ideology, was the primary variable. In the north also, the Afar, under the leadership of Sultan Ah Mirreh Hanafare, opposed the new programme. They were unwilling to accept any fundamental alteration in the usage of their grazing lands. The Afar Liberation Front (ALF) was established and its well-armed population battled with the military and peasant associations when attempts were made to nationalize the land.[16]

According to Peter Schwab, politically, the land reform was a success:

"Overall, the ‘land to the tiller’ programme was welcomed by the peasant population. Redistributing land in the south to the peasantry, and according them ‘possessory rights over the lands they presently till’ (Rural Land Proclamation, Art. 19) in the north was a huge success both in terms of land reform, and in tying the peasantry to the Derg. The Derg took into limited consideration the concern of communal land farmers in the north by granting them possessory rights."[16]

Between 1975 and 1978, a number of bureaucratic and political problems disallowed effective implementation of the land reform programme. These included:

- Opposition to the land reform programme of the participants of the Zemecha Campaign mostly organised via the EPRP

- The War in Eritrea

- Battles in the Ogaden and the Ogaden-War

- Political Opposition in the cities

Economically, the problems are assessed by Haliday and Moleyneux as follows[9]:

"A further problem was that new difficulties arose in the areas of coffee production where up to 25 per cent of the agricultural work force is to be found. Although hiring of labour was henceforward forbidden, the weakness of the state purchasing body, combined with the reliance of the peasantry on their former landlords for their subsistence goods, opened the door to new forms of exploitation of the peasantry by richer peasants and by merchants. overall, the richer peasants were able not only to gain a disproportionate amount of land and to continue exploiting the poorer ones, but also to ensure that it was they who controlled the new Peasant Associations, their credit, equipment and distribution. At the same time, problems of a different kind arose on the state farms, that is, those on which larger-scale commercial farming had previously been practised. These received the majority of agricultural credits, but the total area under cultivation fell from 108,000 hectares in 1975 to 58,000 hectares in 1976-7. This was partly because land previously under state farms was transferred to Peasant Associations, but also partly because of disruption of the pre-existing management systems, which the PMAC was unable to replace."

Food output did not keep pace with population growth in the 1974-1978 period, and Ethiopia faced food shortages in 1977-1979 in the towns and parts of the countryside. This was tackled by the government via the National Revolution Development Campaign.[9]

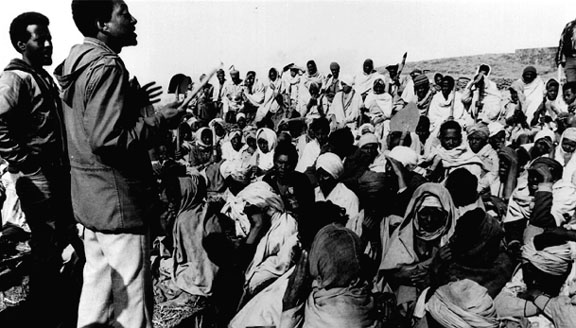

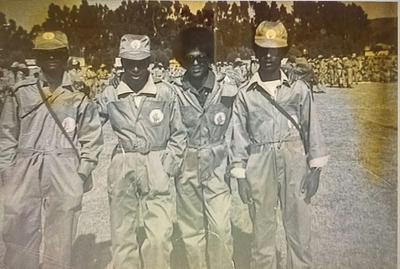

Zemecha-Campaign (1974-1976)

Concurrently and in preparation to the Ethiopian Land Reform, starting from the 21 December 1974[17], the Derg created the Ediget Behibret Zemecha (Development through Cooperation Campaign), which encompassed the closure of the Addis Abeba University in the beginning of 1975, so that 6,000 university students and 50,000 secondary school students could be sent to 437 places in the countryside. This was intended to teach and politicize the peasant, and help develop the rural masses. In the course of the campaign, university students taught peasants about civil rights, land ownership and hygiene, created awareness of land redistribution, and participated in the formation of peasant associations, bringing literacy and building schools, clinics and latrines. The AAU was reopened in the 1976/1977 academic year.[18]

Determining the correct approach to implement the Zemecha was difficult. To this end, Zemecha leaders proposed the following remedies:

- Campaigners were to go only were they knew the roads, cultural traits, lifestyle and languages of the people

- Dissemination of information was to take place at market-places, schools, churches, mosques, religious centers and official gathering places

- Priority was to be given to educating local administrators, spiritual leaders, and influential residents. Speak the language local to the area without a translator[19]

Following advice was given to Zemecha-Campaigners (Amharic: Zemach):

- Speak in the local language without translator

- Do not claim the ability to complete a task when there is the slightest possibility that you could not

- Do not give empty promises

- Be honest and sincere

- Avoid opposing traditional culture, but if absolutely necessary to do so, apply the utmost care as not to arouse the people's ire

- Reject arrogance

- Be receptive towards peoples ideas, but if opposition is called for, make a thorough explanation

- Live like the people

- Do not showcase superiorty in public

- Speak cautiously and be a good listiner

- In oder to explain personal opinions, make use of clear and concise examples

- Show fratenal and filial concern

- Respect Individuals in Private Conversations

- Be Patient

- Think Before you Speak[19]

The Zemecha-Campaign played a major role in the initial phase of the formation of Peasant Associations. Prior to the Land Reform, students were already preparing the peasantry for the expected reform. The timing of the proclamation, at the start of the crop season of the region, and the need to preempt some social classes from organizing themselves to form resistance, necessitated a speady introduction of the Peasant Associations. Zemecha-Campaigners were also those who in the beginning registered those who met state criteria for memebership in the Peasant Associations outlined above.[20] After the students left, these their role was partially taken over by the officials of the political party the Derg had undertaken to create. This embryonic party was known as the Provisional Office for Mass Organizational Affairs (POMOA)[10], and existed between 1975-1979.

Successes

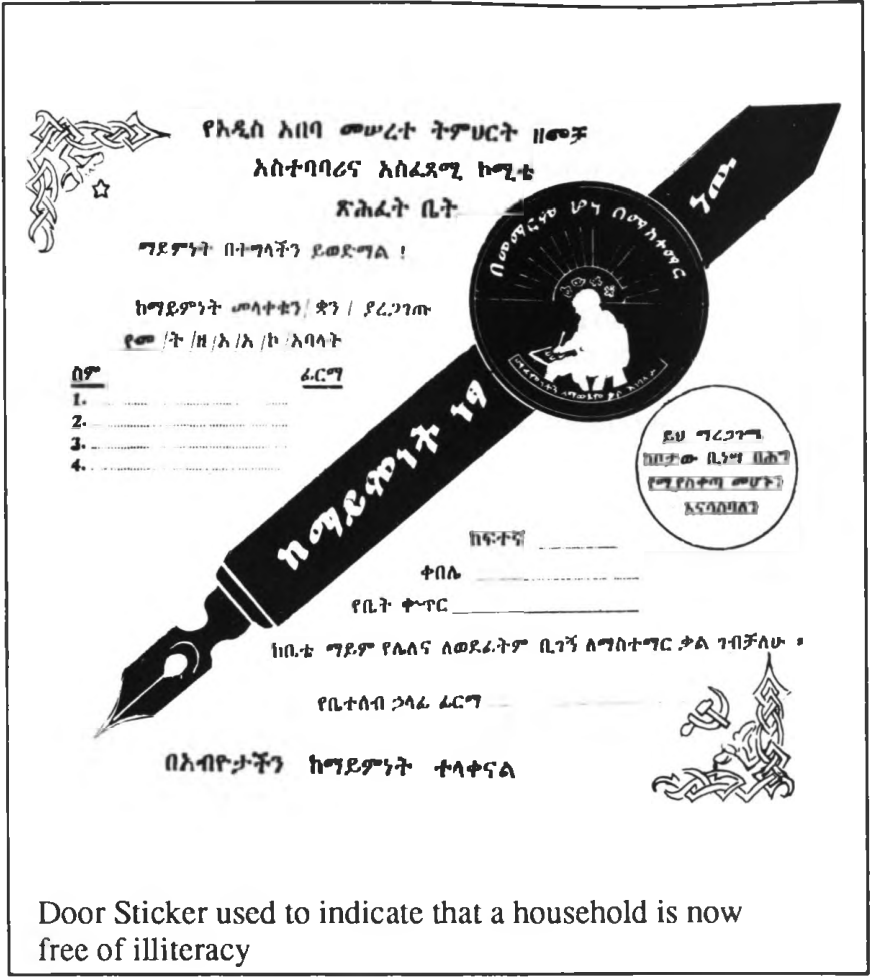

The Zemecha Campaign, via its Alphabetization Program, taught over 350,000 peasants how to read, write, and perform arithmetic in their vernacular language. Initially, six languages were selected for pedagogicial use: Amharic, Afaan Ormo, Tigrinya, Wolaitigna, Somali, Afarigna, Sidamigna and Hadiygna. Teaching material for the first five were completed early in the Zemecha campaign.[19] These 350,000 peasants were only taught by 40% of the campaigners due to political disturbances. Comparing this to the previous government (under Haile Selassie I), which had a literacy rate of 6%, a benchmark which has not been passed in about 60 years of political control, the results were commendable.[22]

The campaigners taught health education to a million people, built 155 schools and 296 clinics (more than 50% of Ethiopias total at the time), trained 1500 midwives, and increased the number of nurses by 40%. They additionally vaccinated 1,250,000 people against various diseases (including 200,000 persons were vaccinated against tuberculosis and 300,000 against smallpox)[23], planted 2,000,000 trees, and vaccinated over 300,000 cattle. Additionally, by late 1975, 6 million people were organized into 19,000 Peasant Associations and 3,700 woman's associations.[22] Additionally, many wells, roads, wooden bridges, meeting halls, latrines, health centres and market places were built, in addition to water pumps, water wheels, wind mills, and even medium range transistor radios, from locally-sourced materials. Total costs for this were 17 Million ETB (at the time 8.5 Million Dollars), one-third of the initially planned cost.[19]

Criticism and issues

116 Campaigners were killed. Sometimes, campaigners were sent to the wrong regions, and were therefore place before linguistic and cultural barriers. The campaigners background, differing widely in age, experience, ability and level of education, were not functionally classified. Some station chiefs were selected only on the basis of educational background, rather than on organisational capacity.

There existed differences in the subjective and objective conditions in different parts of the country. E.g., the proclamation "Land to the tiller" did not carry the same significance for a Tigrean, Gondare or Gojame farmer, as land has been locally controlled for centuries (in contradistinction to the south which only were made part of the Ethiopian Empire through Menelik's conquests, the Agar Maqnat). [19]

This, in addition to the still relatively obscure class distinctions in the north, as strong blood relations tied the farmer to the feudal administrator, and the reforestation programmes, in the heavily eroded landscapes in the north, did not generate the dramatic short term effects that generated enthusiasm for the revolution as elsewhere. This also lead to the campaigners being viewed as outsiders or external threats. Major obstructions also emanated from the former local officials, counterrevolutionary members of the police force, and armed landords. The movement also was subject to sabotage, sometimes emanating from neighboring countries.[19]

Some Zemecha participants were also unwilling to participate, rejecting to work as medical or agricultural personnel, leading to desertions (especially after the Zemecha was extended from the initial one year programme). In total, 69 stations were abandoned, and 6,502 students relocated due to political disturbances, whereas 14 stations composed of 1984 campaigners were closed down due to resistance from the campaigners themselves. A lack of ideological coherence among the students also led to a dissemination of often contradictory political messaging, and some students refused to learn from the masses.[19]

Political and Legal structure

Early Structure of the PMAC (Derg), the POMOA (1975-1978) and the Yekatit 66 School

The Proclamation to Provide for the Establishment of Provisional Military Government of Ethiopia, No.1 of 1974 was issued in September 12, 1974. It did away with the previously existing structures formally via

- (...) although the people of Ethiopia look, in good faith, upon the crown, which has persisted for a long period in Ethiopian history, as a symbol of unity, Haile Selassie, (...) has not only left the country in its present crises by abusing at various times the high and dignifed authority conferred on him by the Ethiopian people (...)

- (...) that the present system of pariamentary election is undemocratic: that the parliament heretofore has been serving not the people and its members but its members and the ruling aristocratic classes(...) that its existence is contrary to the motto "Ityopiya Tikdem" (Ethiopia First)

- (...) that the constitution of 1955 was prepared to confer the Emperor absolute powers; that it does not safeguard democratic rights but merely serves as a democratic facade for the benefit of world opinion (...); and that above all, it is inconsistent with the popular movement in progress under the motto "Ityopya Tikdem" and with the fostering of economic, political and social development. [25]

They therefore suspended the Constitution of 1955, the two Houses of Parliament, deposed Haile Selassie, and established that the armed forces, the police and territorial army council assume full government power until a constitution and government is constituted. They additionally constituted a military court and preliminarily imposed following restrictions[26]:

"Conspiring against the motto Ityopya Tikdem, engaging in any strike, holding unauthorized demonstrations or assembly, and engaging in any act that may disturb public peace and security are prohibited"[25]

In the subsequent declaration, Proclamation No. 2 of 1974, the Derg further established that the could ratify treaties and international agreements, declare war, enact all types of laws, (further elaborated in Proclamation No.12)[27] established an advisory board composed of Ethiopians elected from different profession to advise the Derg on economic, political and social development projects and other national affairs.[28] This was repealed and replaced in 1976 by Proclamation No.108.[26] It establishes the following:

The Provisional Military Administration Council shall be composed as follows

- Congress consisting of all Council members;

- Central Committee consisting of forty (40) Council members elected by the Congress; and

- Standing Committee consisting of seventeen (17) Council members elected by the Congress.

The congress is the highest power in the PMAC and could do the following:

- determine the internal and foreign polices of the country;

- approve the consolidated budget and development plans of the country upon preparation and submission to it by the Council of Ministers;

- determine the strength and policies of the defence and security forces of the country; safeguard the unity of the country;

- ratify, on behalf of Ethiopia, basic economic, political, defence and joint defence treaties and international agreements;

- approve declarations of war, emergency and natural disaster upon preparation and submission to it by the Council of Ministers;

- issue proclamations;

- confirm death penalties, grant amnesty and commute penalties;

- issue directives on the establishment of political par ties and mass organizations;

- decide on the recommendations of the Standing Committee relating to serious measures to be taken against Council members;

- appoint the Chairman, the Vice - Chairmen and the Secretary - General of the Council and dismiss the same.[29]

Ministers and other senior officials designated by the PMAC were made to form the Council of Ministers. They were responsible for decisions made in the Council, and also accountable to congress, central committee and standing committee of the Derg. This Proclamation was repealed in 1977 by Proclamation No. 110, with the ultimate assent of Mengistu Haile Mariam after the execution of Taferi Benti in 1977. Differences were minor, reducing the Central Committee to 32 members, the Standing Committee to 16. Additionally, the Standing Committee now were transferred some of the functions of the Central Committee. The Congress was still the supreme body of the PMAC, and now also the chairman, vice-chairman and secretary general were appointed or dismissed by the congress.[26]

The Derg established a political school, Yekatit 66, and the Provisional Office for Mass Organizational Affairs (POMOA) in December 1975.[1] Both the EPRP and MEISON were represented by supporters on the original 14-person steering committee of POMOA. MEISON had five of its supporters in the steering committee to the EPRP’s two. When the EPRP withdrew from POMOA, as they shortly did, they were replaced by additional MEISON supporters. Other groups represented in POMOA were the WAS (Labor) League, ECHAAT (Oppressed Peoples’ Revolutionary Struggle), MALERED (Marxist-Leninist Revolutionary Organization) and Abyotawit Seded (Revolutionary Flame). POMOA functioned as a forum to involve different Marxist-Leninist organizations in the revolutionary process and to politicize and organize the masses.[2]

The existence of POMOA was publicly revealed on April 21, 1976 following the announcement of the National Democratic Revolution Programme. Initially the organization was known as the People's Organizing Provisional Office. The Yekatit '66 Political School, an institution under the supervision of POMOA, trained political cadres.[1] POMOA functioned as a government department, and received allocations from the state treasury. POMOA's leading organ was directed to organize themselves into four permanent subcommittees in the areas of philosophy dissemination and information, political education, current affairs, and organizational affairs. Also, POMOA was to have branch offices at the provincial, Awrajja and Woreda levels, for which the commission was to review periodic reports on their activities and to which it had to assign cadres. Further mandates of POMOA included: preparing articles and directives on the philosophy of socialism in the languages of various nationalities and disseminating the same; and preparing directives and plans for training of cadres at home and abroad. The developments which were not specifically envisaged by the legislation but which followed in the wake of POMOA's establishment were the launching of its paper (called Revolutionary Ethiopia, Amharic: Abiyotawit Ityopya) and a weekly discussion meeting lasting two hours in all governmental and non-governmental organizations in the country.[30] POMOA had an annual budget of 7 million Birr (3.5 million Dollars at the time).[31]

Haile Fida, the leader of Meison, was the chairman of POMOA. Sennai Likkai of the Waz League served as the vice chairman of the organization.[2]

Union of Ethiopian Marxist–Leninist Organizations (1977-1979)

The Union of Ethiopian Marxist–Leninist Organizations,often also known as the Common Front of Marxist-Leninist Organizations, known by its Amharic acronym Imaledih, was a coalition of communist organizations in Ethiopia active between 1977 and 1979. Through Imaledih, the constituent parties of the coalition would merge. It eventually gave way to thee COPWE. Its constituent parties were WAS (Labor) League, ECHAAT (Oppressed Peoples’ Revolutionary Struggle), MALERED (Marxist-Leninist Revolutionary Organization) and Abyotawit Seded (Revolutionary Flame) and the Maison, the same organizations that were represented in the POMOA. However, whereas POMOA had functioned as a government department, Imaledih was a voluntary association. [32]Imaledih published Yehibret Dimtse ('Voice of Unity') as its party journal. [1]

Its roles were, as outlined by the Yehibret Dimtse, to:

- To raise political consciousness

- Hasten the process of party merger of the parties that joined

- To struggle so that the PMAC accords to the programme of the National Democratic Revolution

- Provide support for "progressive organizations for all anti-feudal, anti-imperialist and anti-bureaucratic capitalist forces"

- "To jointly work in increasing the quantity and improve the quality of cadres who work among the broad masses in all parts of the country; encourage them to learn from them, and to be engaged in production"

- "To strengthen the newly established mass organizations, such as, the workers union, peasant associations and urban dweller-associations so that their exercise of Soviet power is increased and have more participation in governmental affairs; increase their control over the bureaucracy and to enable them to get armed for the defence of the revolution", as well as the youth league, women's associations etc.

- "To support movements of nationalities that accept the Programme of National Democratic Revolution of Ethiopia; to work for the exercise of the rights of nationalities to self-administration in stages beginning from now; to struggle for the training of cadres from oppressed nationalities and enable them to work among their own nationalities; and to struggle for the establishment of an institute of nationalities; to struggle for the right of nationalities to be educated in their respective languages"[33]

It also outlines its foreign policy and military stances.[33]

Meison broke with the Derg and withdrew from the alliance in August 1977. The dismissal of Meison from Imaledih was declared in Yehebret demtse in the same month. Echaat was expelled from Imaledih in March 1978, for differences over political and ideological line. Imaledih was dissolved in February 1979.

COPWE (1979-1984)

The Commission for the Organization of the Party of the Working People of Ethiopia (COPWE), Amharic: የኢትዮጵያ ሰራተኞች ፓርቲ አደራጅ ኮሚሽን, was established by Proclamation No.174 of December 1979. Mengistu Haile Mariam served as chairman. [26] Proclamation No. 174 set the goals, structure, role, rights and duties of the controlling organs and of the rank and file, arranged the relations between the COPWE and the state bodies, between the COPWE and social organizations, and between the COPWE and the Derg.

Along with the establishment of the COPWE, the government also created new mass organisations such as the Revolutionary Ethiopia Women's Association (REWA), the Revolutionary Ethiopia Youth Association (REYA), and strengthened the peasant associations, kebeles, and the All Ethiopia Trade Union.[34]

Among the chief goals of the COPWE was the dissemination and promotion of Marxism-Leninism and the organization of the party of the working people, [35]

“based on Marxism-Leninism and with the historical mission of liquidation of feudalism, imperialism, and bureaucratic capitalism in Ethiopia, the setting up of a people’s democratic republic, and the leading of the masses towards socialism and later to communism.“[36]

Mengistu Haile Mariam was given the power to appoint members of the Central Committee and Executive Committee, and the secretariat; to issue regulations for the admission of ordinary members. The COPWEs role was to

"establish fraternal relationships with Marxist-Leninist parties, liberation movements, and other democratic organizations"[36]

to

"strengthen existing Marxist - Leninist study circles and discussion forums in government and mass organizations; establish new ones, issue directives to them, coordinate their activities and extend to them material assistance; in cooperation with the appropriate government and mass organizations establish, politicise, assist and consolidate professional associations and mass organizations to be effective executors of the directives of the Party of the working people; produce, translate, import and distribute books, periodicals, newspapers, films necessary for the building of a socialist society and other written materials useful for education, political conscious ness, and research"[36]

to

"disseminate among the broad masses the Marxist Leninist ideology free from revisionism, through study circles, discussion forums, government and mass organizations and the mass media; agitate, politicise and organize the various sections of the population by disseminating Marxism Leninism; establish political schools, prepare their cur ricula, train and assign qualified teachers and organize other necessary facilities therefore"[36]

and to

'take all measures necessary to avert any situation which threatens the revolution, the territorial integrity of Ethiopia, or the dignity and welfare of the people in the course of the endeavours to establish the Party of the Working People'.[1]

Fifty-nine of the ninety-three founding members of the COPWE Central Committee were present or former members of the armed forces and police, as were twenty of the thirty alternates, and twenty-seven of these were members of the Derg. The first ten members in order of seniority comprised the Standing Committee of the PMAC, and most of the members of the PMAC Central Committee were also included.

The Executive Committee of COPWE consisted of seven senior Derg officers, who also constituted the Derg Standing Committee (Mengistu, Fikre-Selassie Wogderes, Fisseha Desta, Tesfaye Gebre-Kidan, Berhanu Bayih, Addis Tedla and Legesse Asfaw) as well as four civilians. The latters members were Shemelis Mazengia, Alemu Abebe, Fassika Sidell and Shewandagne Abebe. These four civilians were entrusted with running of the daily affairs of the party. Chief among this group were Shemelis Mazengia, the former editor of the party newsletter, Serto Ader, and by 1985 the head of the Workers Party of Ethiopia's ideological commission; Alemu Abebe, head of the Commission on Worker's Committees in Places of Work; Fassika Sidell, head of the WPE Economic Commission; and Shewandagne Abebe, head of the Institute for the Study of Nationalities.[37]

The question of the delay of the formation of a revolutionary Party is addressed by Mengistu Haile Mariam in 1979 in his address for the formation of the COPWE:

"Many revolutionaries and supporters of the Revolution are bound to wonder why the Party itself should not be set up once and for all. This is a legitimate question. In particular since a Party plays a decisive role in the victory of a revolution, it would have been desirable if it had manifested its existence in the pre-February 1974 period. The heavy sacrifices we have been incurring would have been minimal if ... the Party of the working people of Ethiopia had from the very beginning, been a vanguard force ... but because objective conditions are not governed by mere wish, the Ethiopian Workers' Party did not achieve its existence easily before or in the course of the Revolution" [38]

The first general conference of the COPWE takes place in the summer of 1980. The second takes place in January 1983, and the third and final congress occurred in September 1984. At the conclusion of the Third Congress a celebration of the tenth anniversary of the initiation of the revolution was held, coinciding with the proclamation of the vanguard party, the Workers' Party of Ethiopia. The two Congresses which took place between 1980 and 1983 were attended by 1500 and 1600 delegates representing a wide range of mass organizations (i.e., the All-Ethiopia Peasants' Association; All-Ethiopia Youth Association), the armed forces, and state bureaucracy.[38]

Even before COPWE had given way to WPE, it reached party-to-party agreements with the CPSU - party-to-party agreements are normally reserved for established Marxist-Leninist parties. COPWE cadres were trained in the Soviet Union and other socialist states.[1]

Of the total COPWE membership prior to the Third Plenary Meeting (beginning Nov. 19, 1981), the class composition was recorded as: working class 2.9%; peasant 1.2%; teachers, civil servants, members of the Revolutionary Army and other segments of the society 95.9%. The percentage distribution as of Oct. 10, 1982 , stood at 21.7% for workers; 3.3% for peasants; and 75% for the intelligentsia , civil servants, members of the Revolutionary Army and other sectors of the society.[39] Regionally, the make-up was a follows: By far the largest delegation was that of the armed forces, with over 230 members attending. The next largest groups were of 178 for Addis Ababa and 115 for Shoa, with the other regions accounting for between thirty-six (Illubabor) and eighty-five (Hararghe). Once established, the leadership of COPWE remained extremely stable. Of the ninety-three full Central Committee members appointed in June 1980, eighty-six still belonged to the WPE Central Committee elected in September 1984.[1]

At the central level, the second plenary session of the COPWE Central Committee held in February 1981 marked the point at which the formal announcement of government policies started to come through the party organs rather than through the PMAC - though the PMAC continued to issue appointments and legislation until the formal establishment of the People's Democratic Republic of Ethiopia. The Central Committee issued resolutions on such matters as economic planning and the collectivisation of agriculture, which were then discussed and implemented by subordinate state and COPWE organisations. A party newspaper, Serto Ader, was established, along with an ideological journal, Meskerem, which kept going for three years and produced fourteen issues up to June 1983.[1]

Below the regional level, the COPWE organisation was gradually extended to the larger towns and to provincial, and in some cases even district, government. The first was established in Assab, the port at the southern end of the Red Sea which was administered separately from Eritrea as an autonomous province, in April 1981, represented by a junior Derg member and teacher at the Political School, Eshetu Aleme. COPWE organisations appear shortly afterwards in cities such as Jimma and Dessie, and had been set up in nearly half of the provinces by the time of the second Congress in January 1983. [1] The formation of COPWE primary organisations also accelerated after November 1981, and by June 1982 there were reported to be 436 of them- including organisations in almost all the state-owned factories and all the state farms. There were 162 of these basic organisations, or over a third, established in the armed forces, down to brigade level, where they took over the functions of the previous Military and Political Affairs offices. The training of party cadres was also intensified. In the two-and-a-half years between the first and second Congresses, 2,845 participants graduated from courses at the Yekatit '66 Political School, in addition to those who went to Soviet Union and Eastern Europe. 6,500 study circles were set up in various institutions and localities used for the screening of prospective Party members by 1982.[39]

Workers Party of Ethiopia (1984-1987)

The Workers Party of Ethiopia (Amharic: የኢትዮጵያ ሠራተኞች ፓርቲ, or Ye'Ityopya Serategnoch Parti), was founded on the 12th September 1984. The constitutional congress of the Workers Party of Ethiopia (WPE) was held from 6th to 10th September 1984 and was attended by 1,742 delegates. They approved the statutes, the programme, and the ten year plan of economic and social development of Ethiopia.[35] Its membership initially was estimated to be between 15,000 and 30,000.[38]

Programme of the Workers Party of Ethiopia

The Programme consists of nine parts, and is structured along the following lines[40]:

- Part I: Completing the National Democratic Revolution and Laying Down the Foundation for Socialism

- Part II: The Party's Policy on the Setting up of a New Political System

- Part III: The Party's Policy on Nationalities

- Part IV: The Economic Policy of the Party

- Part V: The Party's Policy in Raising the Standard of Living of the Working People

- Part VI: The Policy of the Party in the Spheres of Ideology, Education, Science, Technology and Culture

- Part VII: The Foreign Policy of the Party

- Part VIII: Building a Defence Force, Safeguarding the Security of the Motherland and the Revolution

- Part IX: Enhancing the Leadership Role of the Workers' Party of Ethiopia

Function and Structure of the Workers Party of Ethiopia

Drafting of the Constitution of the People's Democratic Republic of Ethiopia

A major responsibility of the WPE had been to create a new constitution which would inaugurate the PDRE.[40] A 343-person committee was established by the party with responsibility for drafting the constitution. In June, 1986, the constitutional drafting committee, following a year's work, presented a 119-article draft document. A million copies of the draft constitution were distributed a 20,000 locations and following discussions at the grassroots level, ninety-five amendments were proposed. One of the more controversial provisions was the outlawing of polygamy, which was then retracted. A referendum on the new constitution was held on February 1st, 1987, and three weeks later Mengistu Haile Mariam announced a positive result: 81 per cent of the electorate voted in favour of the new constitution, while 18 per cent voted against.[41]

Administrative Devisions

Ideology and Ideological Struggles

International relations

United States of America

Soviet Union

People's Republic of China

Republic of Cuba

Other Countries of the Socialist Bloc

African Countries

Middle East

Non-aligned movement

Economics and the Effects of Policies

Agriculture and Agricultural Policies

Industrial Policies

Economic Performance, Human Welfare Statistics and Issues

Education and Literacy

The Derg considered education as a key to development and the development of socialism in Ethiopia. This view was first set out in the programme for the National Democratic Revolution in Ethiopia (NDR) in April 1976, and elaborated upon in the the five volume policy documents: General Directives of Ethiopian Education 1980.[42]

An often quoted section in the NDR reads:

"There will be an educational programme that will provide free education, step by step, to the broad masses. Such a programme will aim at intensifying the struggle against feudalism, imperialism and bureaucratic capitalism. All necessary measures to eliminate illiteracy will be undertaken. All necessary encouragement will be given for the development of science, technology, the arts and literature. All the necessary effort will be made to free the diversified cultures of imperialist cultural domination from their own reactionary forces."[43]

A Section in the New Educational Objectives and Directives for Ethiopia 1980 by the Ministry of Education also reads:

1.The general objectives of education should focus on eduation for production, education for scientific conciousness and education for socialist conciousness

2.The content of education should be concerned with polytechnic education that emphasises practice, production, the objective reality of the society.

3.The structure of the education 6-2-4 has to be changed to 8-2-2. The profile of students at each level should be worked out, to this end a curriculum package should be prepared and implemented.[42]

A proclamation providing for the administration and control of schools was issued in 1976. That proclamation was repealed in 1984, and was replaced by the Proclamation for Strengthening of the Management and Administration of Schools. Proclamation No. 103 of 1976 ensured the public ownership of schools.[44]

The two proclamations do not differ in their basic aims, which are to 'integrate education with the lives of the broad masses" and to enhance popular participation in the management of the schools. According to that Proclamation, the management of government schools is made the responsibility of Government School Committees; in the case of public schools, the management is made the responsibility of Public School Management and Administration Committees. In the case of the latter, the majority consists of the representatives of parents. The Ministry of Education retains responsibility for academic matters and for approval of plans of expansion of schools[45]. The responsibilities of the Ministry of Education were more fully explained in he Definition of Powers and Responsibilities of Ministers. Among the functions of the Ministry, the central ones are to:

- 1. Study and prepare educational policy geared to the national political, economic and social needs; prepare a national educational programme and implement the approved policy

- 2. Ensure that the educational curriculum is prepared on the basis of Hebrettesebawinet, and embodies the principle that education given at every level aids to improve the standard of living of the broad masses and emphasize the development of science and technology.

- 4. Ensure that education is given to all on the basis of equality and that it serves as a medium to strengthen unity and freedom and for the interaction of the important cultures of the country...

- 11. Issue and supervise the enforcement of directives relating to the participation of the broad masses in the administration of education at Kebelle, Woreda, Awrajja and provincial levels[45]

Between 1974 and 1981 the number of students in grades 7 and 8 increased by 109%, while the number in grades 9 to 12 increased by 260%. Between 1974 and 1981 the number of secondary school teachers increased by 50%. Today there are about 250 000 students in grades 9 and 10 and about 100.000 students graduate each year from the secondary school system. The great majority, namely, 94%, then come on to the labour market.[46]

Since its establishment in 1977, the Commission for Higher Education has directed attention to two major tasks:

a) maximum utilization of human and material resources by merging various departments and faculties whenever appropriate and

b) expansion of existing facilities' student capacity as well as establishment of new institutions.[47]

Thus, after the revolution, faculties and departments were merged whenever this was economical. In 1977 the departments of English and Ethiopian Languages were combined in the Institute of Languages. In 1980 the Faculty of Engineering and the Building College were merged into the Faculty of Technology, which offered an expanded program that included architecture, town planning, material research, and testing. Also in 1980, the Faculty of Arts, College of Business Administration, and School of Social Work were integrated into the College of Social Sciences, to

"produce the country's high level manpower in the social sciences and [prepare] students to contribute to the ongoing revolution by equipping them with the Marxist- Leninist philosophic background." [47]

The Faculty of Education was changed to the College of Pedagogical Sciences, offering a four-year degree in curriculum studies, educational administration, and educational psychology in addition to a two-year diploma in technical teacher education. The Bahir Dar Academy of Pedagogy was brought under the administration of Addis Ababa University, making it possible for the College of Pedagogical Sciences and the academy to run coordinated programs. All in-service teacher training, extension, and correspondence courses were placed under the Department of Continuing Education. In 1979 the College of Theology was closed.[47]

Addis Abeba University grew to 17 colleges and faculties and an enrollment of 11,588 in 1983. A postgraduate school was opened in 1978, offering a two-year MA. in medicine, science, social science, language studies, and technology. Despite of the War in Eritrea, Asmara University developed three major units, the colleges of Social Science, Natural and Physical Science, and Language Studies. The agricultural colleges at Jimma, Ambo, and Debre Zeit, grew rapidly in response to the increased demand for agricultural experts at the newly established collectives, cooperatives, and state farms.[47]

In 1984 total enrollment in higher education reached 17,000.[47]

The rate of expansion of both primary and secondary education was higher than to the previous Haile Selassie regime. Enrollment increased from 224,934 in 1959–1960 to 1,042,900 in 1974–1975 . During the period of 1975–1979, enrollment increased from 1,042,900 to 3,926,700 or at the rate of about 12% annually.[48]

Every secondary school had a branch of the Revolutionary Ethiopian Youth Association (REYA), with its class representatives and officers elected annually by the student body. The branch is responsible to REYA structures at a higher level, and also to the School Committee, on which a REYA delegate sits as an elected member. The School Committee of eleven members has general control and oversight over the school, and is composed of representatives of local kebeles or peasants associations, REYA and the teachers union. It elects its own Chairman, but the School Director is automatically both the Assistant Chair and Secretary. Thus the school is under the general direction of the local community, but with its administrative arm controlled by the state. This partnership is also expressed in the financing of schools, for while the Ministry of Education pays the teachers’ salaries and provides the buildings, the cost of any materials, resources, educational equipment or the maintenance off furniture is the responsibility of the school. REYA branch itself has the folowing responsibilities: "taking on the tasks of ensuring positive and democratic discipline within the school, mobilising the student body to take part in the school’s productive and democratic life, and organising ‘Labour Education’ - which involves cleaning and maintaining the school, and contributing to work in local factories or farms". The REYA also played a substantial role in the Ethiopian National Literacy Campaign. During the years since its formation in 1980, when it was established out of existing student councils and religious youth organisations, the literacy campaign has been its main social activity, taking over tasks such as the identification of illiterates in households. Early membership ranged to about a million.[49]

A decision to evaluate the educational system was reached in 1983, which was then completed in 1986. This was due to the expansion of secondary education beyond the capacity of the economy a percieved decline in the quality of education.[42] This project was called the Evaluative Research on the General Education of Ethiopia (ERGESE).[50] Alot of the recommendations were already covered by the 1984/1985 Ten-Year Perspective Plan (except some of the language policy questions), and was therefore neglected.[44] The numerical targets of the plan were to achieve participation rates of 66.5 percent in the first level of education, 35.6 percent in Grades 7 and 8, 11.5 percent in grades 9 and 10 and 7.9 percent in Grades 11 and 12. The plan also projects the attainment of over 90 percent literacy by 1993/94.[45]

The Dergs education system was inhibited by problems such as budget shortfalls, which in turn affected the supply of basic educational materials including textbooks and a shortage of qualified teachers both at primary and secondary schools.[44]

A major inspiration for the educational system was the GDR (German Democratic Republic).

Ethiopian National Literacy Campaign

One of the significant contributions of the Derg was its launching of a vigorous national campaign against illiteracy (also known as the Ethiopian National Literacy Campaign) in 1979.[45] Initial planning of the campaign set ambitious targets of eradicating illiteracy from all urban areas by 1982, and from rural regions by 1987. The latter date was later revised and re-set for 1990.[51]

The official aims of the National Literacy Campaign (started in 1979) was the following: