More languages

More actions

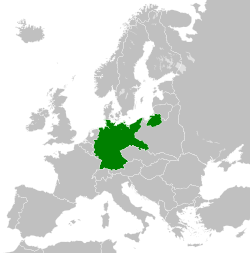

| German Reich Deutsches Reich | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1918-1933 | |||||||||||

|

Flag | |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Capital | Berlin | ||||||||||

| Official languages | German | ||||||||||

| Government | Federal semi-presidential republic (1919-1930) Federal presidential republic under rule by decree (1930-1933) | ||||||||||

| President | |||||||||||

• 1919-1925 | Friedrich Ebert | ||||||||||

• 1925-1933 | Paul von Hindenburg | ||||||||||

| Chancellor | |||||||||||

• 1919 (first) | Philipp Scheidemann | ||||||||||

• 1933 (last) | Adolf Hitler | ||||||||||

| Legislature | Reichstag | ||||||||||

| Reichsrat | |||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||

• Established | 9 November 1918 | ||||||||||

| 11 August 1919 | |||||||||||

• Rule by decree begins | 29 March 1930 | ||||||||||

• Hitler is appointed Chancellor | 30 January 1933 | ||||||||||

| 27 February 1933 | |||||||||||

| 23 March 1933 | |||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||

• Total | 467,787 km² | ||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||

• 1925 estimate | 62,411,000 | ||||||||||

• Density | 133.129 km² | ||||||||||

| Currency | Papiermark (1919-1923) Rentenmark and Reichsmark (1923/24 - 1933) | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

The German Reich (German: Deutsches Reich) from 9 November 1918 to 23 March 1933, commonly known as the Weimar Republic (German: Weimarer Republik), was a federal semi-presidential republic, with rule by decree beginning on 29 March 1930.

With the Enabling Act being enacted on 23 March 1933, giving the Chancellor, Adolf Hitler, the authority to create and enforce laws without the consent of the legislature or the President, the Weimar Republic was effectively dissolved.[1]

Name[edit | edit source]

The name of the country remained unchanged from the imperial era, due to various factions vying for power being unable to decide upon a name, however the official name was rarely used.[2]

The Social Democratic Party of Germany (SDP) favoured the term "Deutsche Republik" (German Republic), with this becoming the most commonly used term for the country.[2]

The Centre Party (Zentrum) preferred "Deutscher Volksstaat" (German People's State).[2]

The terms "Republik von Weimar" (Republic of Weimar) and "Weimarer Republik" (Weimar Republic) were first coined by Adolf Hitler in early 1929.[2]

History[edit | edit source]

Background[edit | edit source]

After four years of war on multiple fronts in Europe and throughout the world, the final Allied offensive, the Hundred Days offensive, began in August 1918. The position of Germany and the rest of the Central Powers continued to rapidly deteriorate.

Awareness of impending military defeat quickly spread, and when a naval order was issued on 24 October 1918 (Op. 269/A I),[3] intending to prepare for a final, decisive battle, between the German High Seas Fleet and the British Grand Fleet, sailors mutinied.

News of the mutinies spread, triggering a general revolutionary spirit to spread, which led to the toppling of the monarchy, and the beginning of the November Revolution.

November Revolution (1918-19)[edit | edit source]

As news of the Kiel mutiny spread, sailors, soldiers, and workers throughout Germany began to organize Workers' and Soldiers' Councils (Arbeiter und Soldatenräte), which were modelled after the Soviets of the Russian Revolution. The revolution spread throughout Germany, with participants seizing control of military and civil powers in many cities.

Opposition of the SPD to the socialist revolution[edit | edit source]

With revolutionary fervour at its peak, the formation of a socialist German republic seemed inevitable.

The Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD), who had already betrayed many of its principles four years prior, when it backed Germany's entry into the First World War, encouraged affiliated trade unions to refrain from striking, and agreed not to criticize the government or the war, under the policy of Burgfriedenspolitik (literally "Castle peace politics", referring to a political truce between all parties).

Opposition to Burgfriedenspolitik came initially from Karl Liebknecht, the son of the SPD's founder, Wilhelm Liebknecht, being joined later by Otto Rühle, Rosa Luxemburg, Clara Zetkin, and others. They went on to found the Spartacus League (German: Spartakusbund), which was renamed as the Communist Party of Germany (German: Kommunistiche Partei Deutschlands, KPD) at its first party congress, from 30 December 1918 to 1 January 1919.

On 9 November 1918, Karl Liebknecht proclaimed the Free Socialist Republic of Germany at the Berliner Stadtschloss. Two hours earlier, the "German Republic" had been proclaimed by Philipp Scheidemann at the Reichstag building. Leader of the SPD, Friedrich Ebert, was opposed to the proclamation of a republic,[4] and even asked Prince Maximilian, regent of the German Empire to keep his position as regent.[5]:90

A day later, on 10 November 1918, Friedrich Ebert signed a deal with Wilhelm Groener, Quartermaster General of the German Army. Ebert promised Groener that he would crush the revolution, dismantle the Workers' and Soldiers' Councils, and ensure the continued authority and autonomy of the army in exchange for the army's loyalty.[5]:120-121[6]

Having allied themselves with reactionary forces, Ebert and the SPD focused on crushing the revolution. On December 24, on Ebert's order, the Reichsmarinedivision, a military division that had rebelled due to outstanding pay and the quality of their accommodation, was attacked by regular troops.[5]:139-147

From January 9 to January 12, regular troops and the Freikorps, led by Gustav Noske, the SPD's Defence Minister, bloodily suppresed the Spartacist Uprising.[5]:163 On January 15, members of the Freikorps, murdered Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg on Noske's order.[5]:169-182

Gustav Noske ordered the Freikorps to violently put down any unrest following the murder of Liebknecht and Luxemburg.[5]:183-196

Economy[edit | edit source]

Inflation[edit | edit source]

After the First World War, Germany had to pay debt to the Allies in foreign currencies. It could not earn enough money because of tariffs, so it attempted to print Reichsmarks in order to pay its debt. Hyperinflation destroyed the mark's exchange rate, leading import prices to increase. The Reichsbank then printed even more money to make it practical to sell basic goods like food.[7]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ von Lüpke-Schwarz, Marc (2013-03-23). "The law that 'enabled' Hitler's dictatorship" Deutsche Welle. Archived from the original on 2022-03-23.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Schnurr, Eva-Maria (2014-09-30). "Der Name des Feindes: Warum heißt die erste deutsche Demokratie eigentlich 'Weimarer Republik?" Der Spiegel (in German).

- ↑ Grant, U-Boat Intelligence, pp. 163-64 Gladisch, Nordesee, Bd.7, pp. 344–347

- ↑ Sturm, Reinhard (2011-12-23). "Weimarer Republik" Informationen zur Politischen Bildung. Archived from the original on 2018-08-10.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 Haffner, Sebastian (2002). Die deutsche Revolution 1918/19. Kindler. ISBN 3-463-40423-0

- ↑ Historical Exhibition presented by the German Bundestag

- ↑ Ben Norton, Michael Hudson (2023-05-10). "NY Times is wrong on dedollarization: Economist Michael Hudson debunks Paul Krugman’s dollar defense" Geopolitical Economy Report. Archived from the original on 2023-05-10.