Great Socialist People's Libyan Arab Jamahiriya (1977–2011)

More languages

More actions

| Socialist People's Libyan Arab Jamahiriya (1977–1986) الجماهيرية العربية الليبية الشعبية الاشتراكية Great Socialist People's Libyan Arab Jamahiriya (1986–2011) الجماهيرية العربية الليبية الشعبية الإشتراكية العظمى | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1977–2011 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Capital and largest city |

| ||||||||

| Official languages | Arabic | ||||||||

| Religion | Islam | ||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Libyan | ||||||||

| Dominant mode of production | Socialism | ||||||||

| Government | Unitary Islamic Socialist Jamahiriya | ||||||||

| Leader of the Revolution | |||||||||

• 1979 – 2011 | Muammar Gaddafi | ||||||||

| Secretary of the General People's Congress | |||||||||

• 1977 – 1979 | Muammar Gaddafi (first) | ||||||||

• 2010 – 2011 | Mohamed Abu al-Qasim al-Zwai (last) | ||||||||

| Secretary of the General People's Committee | |||||||||

• 1977 – 1979 | Abdul Ati al-Obeidi (first) | ||||||||

• 2006 – 2011 | Baghdadi Mahmudi (last) | ||||||||

| Legislature | General People's Congress | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

• Established | 1977 | ||||||||

• Dissolution | 2011 | ||||||||

| Area | |||||||||

• Total | 1,759,541 km² | ||||||||

| Population | |||||||||

• 2010 estimate | 6,355,100 | ||||||||

| Currency | Libyan Dinar | ||||||||

| |||||||||

The Great Socialist People's Libyan Arab Jamahiriya, commonly known as the Libyan Arab Jamahiriya, was a socialist state in North Africa from 1977 to 2011 established by Muammar Qaddafi following the ratification of the Declaration of the Establishment of People's Authority by the General People's Congress. Initially one of the poorest countries in the world prior to the September Revolution, by 2010 Libya achieved the highest human development index of any country in Africa.[1][2][3]

Created on the basis of Third International Theory, the Jamahiriya was a direct democracy guided by people's congresses and committees, which were voluntary meetings of adults in local communities that dictated public policy and sent delegates to the national legislature. The Libyan Jamahiriya was intended to be a catalyst for the "Era of the Masses," being the stage in human development in which parliamentary republics and monarchies across the world have been eradicated and replaced with direct democracies.

History[edit | edit source]

Start of the Popular Revolution and Declaration of People's Authority[edit | edit source]

See also: Libyan Cultural Revolution, Declaration of People's Authority

On the anniversary of the Prophet Muhammad's birth, Muammar Gaddafi held a rally in which he declared the beginning of Libya's transformation. During his speech in Zwara, Colonel Gaddafi called for a new popular revolution in the Libyan Arab Republic. Major points presented during the speech included the following: the suspension of all laws due to their reactionary character, the purging of the "politically sick" capitalists and communists, the distribution of arms among the masses, the destruction of the bureaucratic administrative barriers between the masses and the state, and the start of a cultural revolution promoting the values of socialism and Islam. Gaddafi also stressed that Libyans would become the first peoples to implement a unique revolution in which the armed masses assume the responsibility of ruling and that Libya will challenge the material force of the United States. Gaddafi also intended for the Popular Revolution to be part of a greater Pan-Arab revolution against the West and neo-colonialism. Due to Gaddafi's encouragement, newly formed people's committees actively burned books that didn't conform to the values of the Libyan Cultural Revolution.[4]

The popular revolution eventually culminated into the development of people's congresses and committees and the Declaration of People's Authority, the legal document which officially ended the Libyan Arab Republic and started the Libyan Arab Jamahiriya.[4]

Libyan-Chadian War[edit | edit source]

See also: Libyan-Chadian War

2000s[edit | edit source]

Arab Spring[edit | edit source]

The US and UK forced Gaddafi to give up his nuclear weapons program in order to have better foreign relations and attract international investment. With no way for Libya to defend itself, NATO funded terrorists to overthrow and brutally murder Gaddafi.[5]

Government[edit | edit source]

People's Congresses[edit | edit source]

See also: Basic People's Congress, Non-Basic People's Congress

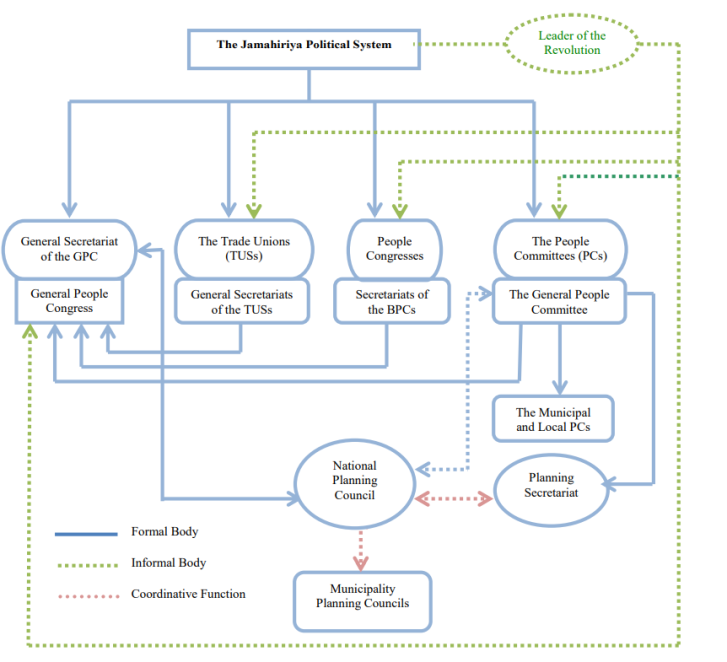

The first formal principle body of the Jamahiriya political framework, the People's Congresses, are mass organizations on a local scale comprising of all registered adults in a local community. It is the smallest, most basic unit of administration in Libyan society. Congresses are organized on the basis of population density, need for services and availability of resources necessary as a means of ensuring the efficiency of the Jamahiriya system. Due to this, the number and size of People's Congressional boundaries may increase or decrease. The People's Congresses had legislative authority and directly considered all domestic and foreign policy issues. Every People's Congress selected a Secretariat to lead the congress and Local People's Committee to supervise and run public services. Two annual meetings of the congresses were to be scheduled by necessity, the first set up to discuss local businesses and set an agenda for the next meeting while the second meeting fills Local People's Committee seats and discusses national and international policy.[6]

People's Congresses located in the same municipality would form a Municipal People's Congress, which is the gathering of People's Congresses, Committees and Trade unions in the area. Each Municipal people's Congress elects a secretariat to lead the congress and a Municipal People's Committee to manage public services within city boundaries.[6]

People's Committees[edit | edit source]

See also: Basic People's Committee, Non-Basic People's Committee

The second formal principle body of the Jamahiriya political framework, the People's Committees, are the executive arms of the people's committees tasked with the implementation of congressional decisions. The People's Committees are elected directly by the congresses and are headed by a Secretary General. People's Committees have the power to use all economic, social and financial resources to reach policy aims.[6]

At the national level, the General People's Committee is the executive branch of government and equivalent to a Cabinet of Ministers. They are responsible for the operation, performance and activity of ministry level departments. Though their primary focus is implementation, the General People's Committee has the power to propose new legislation/policies as well as amendments to General People's Congress decisions.[6]

Trade Unions and Syndicates[edit | edit source]

The third formal principle body of the Jamahiriya political framework, the Trade Unions and Syndicates, are established by the organization of all Libyan workers into professional associations. Each union would elect their own secretariat to manage affairs and serve as a self-regulatory committee of sorts. Trade Unions and Syndicates were organized in all labor sectors in the Jamahiriya and would appoint a Secretary General to represent them and defend their rights as workers. In practice, Unions and Syndicates were established in the municipal level, with each union sending delegates to participate in the general labor federations of the national level. Professional associations in the Jamahiriya delivered its own secretariat to congressional meetings to represent their interests and speak on issues relevant to their field of work. Their views and demands would take final form in the General People's Congress where they present policy issues during the annual gathering of the congress.[6]

General People's Congress[edit | edit source]

See also: General People's Congress, General People's Committee

The fourth formal principle body of the Jamahiriya political framework, the General People's Congress, is a gathering of the secretaries of the Basic People's Congresses, Municipal People's Congresses, People's Committees as well as the Trade Unions and Syndicates. The General People's Congress meets annually, in which it selects and questions members to be appointed to the General Secretariats of the Congress and Committee, as well as higher court judges. The General People's Congress Secretariat is responsible for managing the Congresses activities, such as signing legislation, establishing an agenda of the Basic People's Congresses and organizing sessions. The General People's Committee Secretariat comprises of General Committees tasked with managing daily life and executing the Congress' decisions; its Secretaries are the foreign equivalent to Cabinet Ministers. After all motions have been heard, discussed and voted on, the conclusion of the summit is followed by the transferring of these plans to the General People's Committee to begin the implementation process. Therefore, as the highest legislative and political authority in the Jamahiriya, policies cannot be valid before approval by the General People's Congress.[6]

Leader of the Revolution[edit | edit source]

See also: Brotherly Leader and Guide of the Revolution

An honorary position outside of the official political framework of the Jamahiriya, the Leader of the Revolution acts as an ideological guide, teacher and representative of Third International Theory. Outside of Gaddafi's official role as Higher Commander of the Armed Forces, his role in politics was that of an informal advisor to the General People's Congress and at times the Secretariat of the General People's Committee.[6] Even among Western academics, historian Lillian Harris, who authored Libya: Qhadafi's revolution and the modern state, noted that Gaddafi didn't hold any political authority in the Jamahiriya process. Despite attempting to make the argument that Gaddafi was still a dictator pulling the strings by claiming that Gaddafi could override the General People's Congress, she admitted that after Gaddafi's proposals to the congress were all rejected his response was holding protests across the country to express criticism. Immediately following these demonstrations, the congress held a special session and voted to approve only one of Gaddafi's three proposals.[7]

Administrative divisions[edit | edit source]

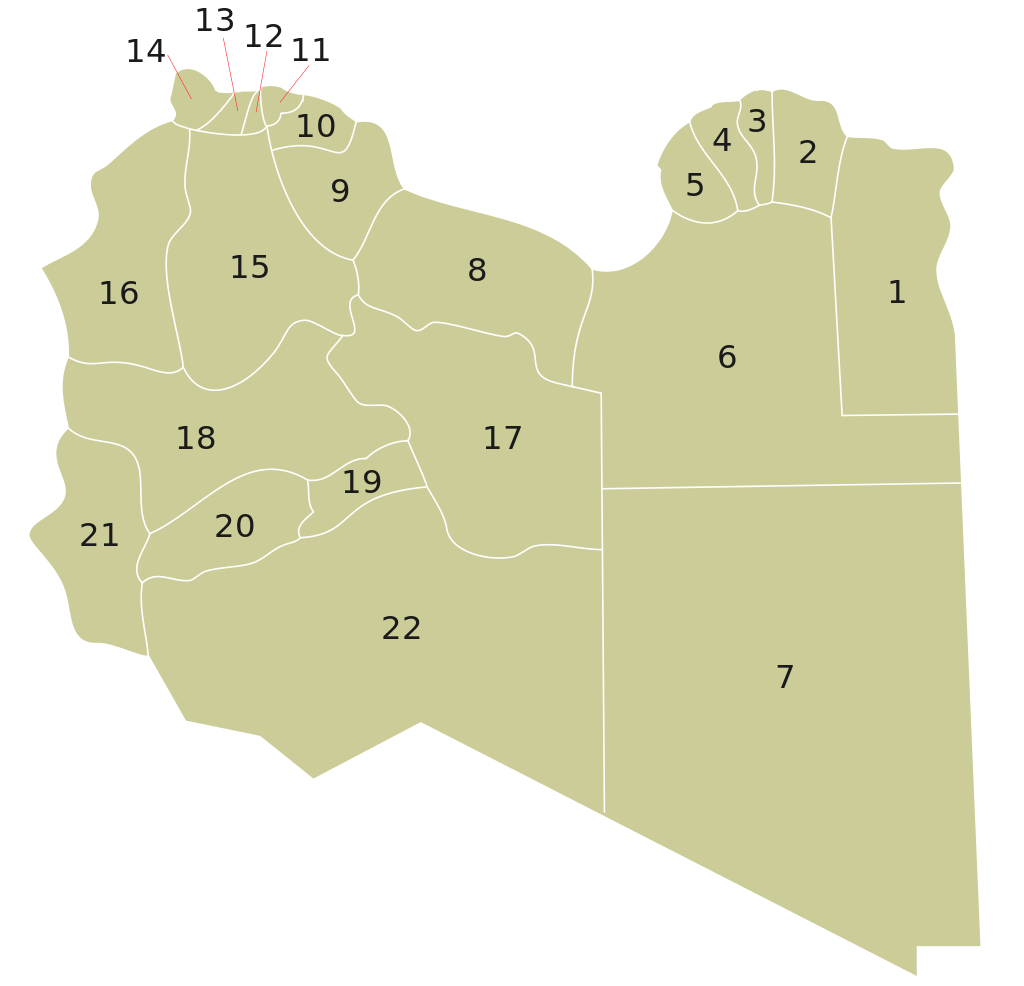

Shabiyat, or people's districts, were the administrative divisions of the Libyan Arab Jamahiriya since 1995 and remained until 2 years after the country's dissolution as a result of the Libyan Civil War. Inside the people's districts were a plethora of people's congresses, of which the district leaderships were tasked with organizing.

| District | Map of the Jamahiriya Districts between 2007 and 2011 | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Al Butnan |

|

| 2 | Darnah | |

| 3 | Al Jabal al Akhdar | |

| 4 | Al Marj | |

| 5 | Benghazi | |

| 6 | Al Wahat | |

| 7 | Al Kufrah | |

| 8 | Sirte | |

| 9 | Misrata | |

| 10 | Marqab | |

| 11 | Tripoli | |

| 12 | Al Jafarah | |

| 13 | Az Zawiyah | |

| 14 | An Nuqat al Khams | |

| 15 | Nafousa Mountain | |

| 16 | Nalut | |

| 17 | Al Jufrah | |

| 18 | Wadi ash Shati' | |

| 19 | Sabha | |

| 20 | Wadi al Hayat | |

| 21 | Ghat | |

| 22 | Murzuq | |

Economy[edit | edit source]

"Libya's great merit as a case study is as a prototype of a poor country. We need not construct abstract models of an economy where the bulk of the people live on a subsistence level, where per capita income is well below US$ 50 per year, where there are no sources of power and no mineral resources, where agriculture expansion is severely limited by climatic conditions, where capital formation is zero or less, where there is no skilled labor supply and no indigenous entrepreneurship... Libya is at the bottom of the range in income and resources and provides a reference point for comparison with all other countries" — Benjamin Howard Higgins

Following the Great September Revolution, the discovery of oil and the exploitation and development of these resources by Western enterprises would allow the new Revolutionary Command Council (RCC) led government to begin a campaign for rapid development of indigenous manpower and industrial sectors in the aftermath of the nationalization of western oil companies. The General People's Congress would continue prioritize the availability of goods and services to the masses rather than to drive up profits.[8]

Planning[edit | edit source]

The Libyan economy was gradually transformed from a neo-colonized capitalist framework to socialist planned economy. As 5 year plans were introduced to develop Libyan infrastructure and previously neglected sectors of the economy since the discovery of oil, the new government significantly increased the size and role of the public sector as nationalization of foreign enterprises came into fruition. Public ownership over productive forces would reach its peak in the 80s, as most industries would be managed by State Owned Enterprises or People's Congresses. From this point the public sector would come to dominate all sectors of production in Libya.[8]

Agriculture[edit | edit source]

Prior to the discovery of oil in 1959, Libya's economy was primarily based on agricultural produce. Due to Libya's lack of fertile lands, agrarian production was severely limited, making Libya one of the poorest countries in the world of that time. In the aftermath of nationalization policies after the dissolution of the Senussi Dynasty, the oil wealth generated by National Oil Corporation would allow for increased development of previously neglected agrarian sectors. Throughout the rest of the Jamahiriya's history, agriculture would be allocated the most funds for development projects; allowing for the expansion of center-pivot irrigation projects and the creation of the Great Man-Made River.[8]

Housing and construction[edit | edit source]

Housing was considered a human right in Libya, as Third International Theory considers private ownership of human necessities another form of enslavement of the masses. The Great Green Charter for Human Rights also declared that all rent breaches the rights of the people and that a house belongs to those who occupy it.[9]

In the immediate aftermath of the September Revolution and the oil boom of the '70s, immense public spending was invested into the development of the construction industry, as the Libyan government sought the development of national infrastructure. The result was a construction boom, which saw the creation of housing, schools, hospitals and other facilities. In 1975, the government put forward a program to reorganize the construction industry. At the start of this, there were 2,000 contractors which mostly organized on a sole trader of partnership basis. Housing administrators had the power to amalgamate construction firms, causing a smaller number of larger companies in Libya, enabling smaller ventures to conduct larger construction projects. Firms accumulating a capital excess of 30 thousand Libyan Dinars were merged into larger corporations and the majority of shares were sold to the government. The enactment of the 1978 Housing Law, which limited families to a single residence, also eliminated private residential construction. The 80s saw the continued nationalization of local construction enterprises and cutbacks on foreign labor. Five years later, due to slow performance within the oil industry, Libya's construction industry saw a slow period which would last for two decades. Despite continued ambitious construction projects, only 15.6% of planned units were developed during this period.[10]

Industry and manufacturing[edit | edit source]

Market reforms[edit | edit source]

By the late 90s to early 2000s, the Libyan Arab Jamahiriya would begin to open up its economy after taking responsibility for the Lockerbie Bombing as a means of getting rid of Western sanctions which plagued attempts of development by the Jamahiriya. International sanctions spearheaded by the United States led to a period of economic stagnation and failure to reach over half of the country's productivity aims.[11] The ratification of law 9 of 1992 on partnerships provisions by the General People's Congress marked the beginning of the relaxation on private enterprises. Law 5 of 1997 on encouragement of foreign capital investment was also enacted years later in an attempt to attract foreign capital into the country.[8] Government encouragement of private investment in the construction industry would also begin to take place, ending the complete abolition of private contractors and bringing back reliance on foreign experts.[10]

Infrastructure[edit | edit source]

Transportation[edit | edit source]

As transportation access was considered a human right within the Jamahiriya, cars for low-income government workers were provided for by the government.[12]

Energy[edit | edit source]

Demographics[edit | edit source]

Living standards[edit | edit source]

By the '90s, income disparities had been diminished due to extensive social support and subsidies by the government, ranging from higher pensions, and cheap necessities such as housing, transportation, water and electricity. Prior to the Libyan civil war, it was speculated that Libya's gradual market reforms could alter these support networks guaranteed by the government.[12]

Education[edit | edit source]

In 2009, the adult literacy rate was 88.4% and the youth literacy rate was 99.8%. 52% of men and 57% of women went to colleges or universities.[13] The government funded students to study abroad for free.[14]

Health[edit | edit source]

The Libyan Arab Jamahiriya had free universal healthcare for all citizens, as healthcare was considered a human right in Jamahiriya society. Due to considerable investment made during the Gaddafi administration, and continued expansion of the healthcare apparatus by later governments, in 1978 Libya had erected 50 per cent more hospitals than it had in 1968, while the number of doctors had increased from 700 to over 3000 in that decade. Malaria was eradicated, while trachoma and tuberculosis were curtailed greatly.[15] Child mortality rate would also decreased from 71 per 1,000 live births in 1991 to 14 in 2009.[16] Undernourishment was less than 5% and the average citizen ate over 3,000 calories per day. Life expectancy was 74.5 years,[17] the highest in the developing world.[18] Women received $5,000 after the birth of every child.[14] Due to international sanctions, healthcare quality in Libya began to erode, however, better off Libyans often traveled to neighboring Tunisia and Egypt for medical treatments. In 1999, 393 children were infected with HIV in a Benghazi hospital during blood transfusions supervised by Bulgarian nurses and a Palestinian doctor. The medical team was convicted of criminal negligence and condemned to death before international pressure forced the Libyan government to release them in 2007. Despite economic reforms in the country, the Libyan government planned to expand health services and spending in 2002. Prior to the dissolution of the Jamahiriya, 99% of one-year old children were vaccinated against tuberculosis and 93% against meningitis.[12]

Human rights[edit | edit source]

Women[edit | edit source]

Inspired by the the ideological calls for gender equality enshrined in The Green Book and reinforced by religious interpretation, the the General People's Congress issued the Document on the Rights of Women in Jamahiriya Society, which guaranteed the rights of women in Libya.[19] These rights were also supported by the Great Green Document for Human Rights in the Age of the Masses.[20] Within all congresses in Libya, Secretaries for Women's Affairs were elected to carry out government programs to strengthen women's position in governance, education and the workplace. Regular investigation into the grievances of women took place and commissions were established to propose solutions to said issues.[21]

Imperialist attacks[edit | edit source]

In 1986, the United States under Ronald Reagan bombed Libya.[22]

In January 2011, Arab Spring protests spread from Tunisia to Libya. The protests were mostly in the Benghazi region and were supported by the United States and European Union. Between March and October, NATO ran a bombing campaign in Libya. On 20 October 2011, rebels captured and brutally murdered Qaddafi.[17]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ United Nations Development Programme (2010). Human Development Report 2010. [PDF]

- ↑ “When analysing the standard of living in Libya it is important to put the achievements into context. During the 1950’s under the leadership of King Idris, Libya was amongst the poorest nations in the world with some of the lowest living standards. From the early 1980’s until 2003 Libya were placed under heavy sanctions by the US and UN which had the result of strangling Libya’s growing economy leading to an inevitable smothering of development projects and social welfare schemes. Despite this The Libyan Arab Jamahiriya achieved the highest living standard in Africa. Libya has also invested heavily in African development initiatives. The funding of infrastructure projects as well as African political and financial institutions was aimed at developing Africa independently and combating the economic exploitation of African resources and labour by outside powers.”

Alexandra Valiente (2011-11-09). "Celebrating The Great Achievments Of Muammar Gaddafi" Libya 360º Archives. Retrieved 2022-04-23. - ↑ “The 2010 UN Human Development Index – which is a composite measure of health, education and income – ranked Libya 53rd in the world, and first in Africa.”

Mahmood Mamdani (2011-04-09). "Libya after the NATO invasion" Al Jazeera. - ↑ 4.0 4.1 George Lenczowski Popular Revolution in Libya University of California Press. Retrieved 2023-18-5

- ↑ Stephen Gowans (2018). Patriots, Traitors and Empires: The Story of Korea’s Struggle for Freedom: 'Byungjin' (pp. 213–214). [PDF] Montreal: Baraka Books. ISBN 9781771861427 [LG]

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 Abuagela M. Ahmed (2012-12-05) Examination of the public policy process in Libya University of Salford. Retrieved 2023-3-17

- ↑ “Qadhafi 's response was swift. He publicly denounced the lack of revolutionary zeal on the part of certain "reactionary forces" and by March had organized "popular demonstrations" demanding implementation of the rejected proposals. A special session of the GPC quickly approved compulsory military training for all students, and by the end of 1984 the official media was claiming that the "Militarization of the People Law" had been approved by the basic people's congresses and by students' and women's congresses at their first sessions in 1984. Meanwhile, although efforts to abolish formal elementary education were shelved, at least some measures geared toward implementation”

Lillian Craig Harris (1986). Libya : Qadhafi's revolution and the modern state. Westview Press. - ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Nassr Saleh Mohamad Ahmad (2004-7-05) Corporate Environmental Disclosure in Libya: Evidence and Environmental Determinism Theory Al-Jabal A1-Gharbi University. Retreived 2023-3-19

- ↑ The Great Green Charter of Human Rights

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Libya Construction Industry Libyan Heritage House. Retrieved 2023-18-5

- ↑ HE PROCESSES OF MANAGEMENT ACCOUNTING CHANGE IN LIBYAN PRIVATISED COMPANIES: AN INSTITUTIONAL PERSPECTIVE

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Libya - Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

- ↑ UIS Statistics in Brief. UNESCO. Archived from the original on 2010-09-11.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Steven Meltzer (2014-05-16). "Ten Things You Didn’t Know About Libya Under Gaddafi’s So-Called Dictatorship" Urban Times. Retrieved 2022-04-24.

- ↑ Bearman, Jonathan (1986). Qadhafi's Libya. London: Zed Books

- ↑ World Health Organization (2007). Libyan Arab Jamahiriyah. [PDF]

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 "Libya: Before and After Muammar Gaddafi" (2020-01-15). TeleSur. Archived from the original on 2021-03-05. Retrieved 2022-06-25.

- ↑ Alexandra Valiente (2011-11-09). "Celebrating The Great Achievments Of Muammar Gaddafi" Libya 360º Archives. Retrieved 2022-04-23.

- ↑ Document on the rights and duties of women in Jamahiriya society

- ↑ The Great Green Document for Human Rights

- ↑ The executive regulations of Law No. 1 of 1375 FDP

- ↑ John Pike. "Operation El Dorado Canyon" GlobalSecurity.org. Retrieved 2022-03-30.