More languages

More actions

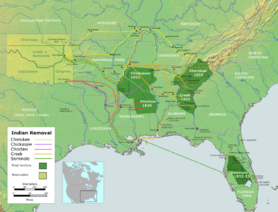

The Indian Removal Act refers to a law of the United States of America which was signed into law by President Andrew Jackson on May 28, 1830, which authorized the confiscation of land from Native people by settlers, and provided resources for their forced removal which was largely conducted by the U.S. military.[1]

The forced relocation placed more than 25 million acres of fertile, lucrative farmland into the hands of the mostly white Euro-American settlers in Georgia, Florida, North Carolina, Tennessee, Alabama, Mississippi, and Arkansas. More than 46,000 Native Americans were forced by the US military and other settler groups to abandon their homes and relocate to "Indian Territory" which eventually became the state of Oklahoma.[2] Settlers employed tactics of gathering people in camps and plundering and burning their homes in order to force them to leave so that the settlers could take their land, engaging in acts of ethnic cleansing and genocide.

Trail of Tears[edit | edit source]

During the fall and winter of 1838 and 1839, when the Cherokee were forcibly moved west by the United States government. Approximately 4,000 Cherokee people died on this forced march, which became known as the Trail of Tears.[3] The removal which targeted the Cherokee people was implemented by 7,000 troops commanded by General Winfield Scott. Scott's men moved through Cherokee territory, forcing many people from their homes at gunpoint. As many as 16,000 Cherokee were thus gathered into camps while their homes were plundered and burned by Euro-American settlers. Subsequently those refugees were sent west in 13 overland detachments of about 1,000 per group, the majority on foot, enduring inadequate food supplies, shelter, and clothing, suffering especially bad conditions after frigid weather arrived. Escorting troops refused to slow or stop so that the ill and exhausted could recover. Additionally, the refugees had to pay farmers for passing through lands, ferrying across rivers, and even for burying their dead.[4]

See also[edit | edit source]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ “Indian Removal Act (1830) - Immigration History.” Immigration History. January 31, 2020. Archived 2022-11-03.

- ↑ “May 28, 1830 CE: Indian Removal Act | National Geographic Society.” Nationalgeographic.org.

- ↑ “Research Guides: Indian Removal Act: Primary Documents in American History: Introduction.” 2019. Library of Congress. Archived 2022-11-03.

- ↑ “Cherokee | History, Culture, Language, Nation, People, & Facts | Britannica.” Encyclopædia Britannica.