More languages

More actions

(History) Tag: Visual edit |

(Map) Tag: Visual edit |

||

| (One intermediate revision by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

=== Early contact with settlers === | === Early contact with settlers === | ||

[[File:Five Nations map.png|thumb|Map of pre-colonial Cherokee territory (darker gray)]] | |||

The Cherokee became suspicious of the [[Kingdom of England (927–1707)|English]] when [[Settler colonialism|settlers]] infected their towns with smallpox and alcohol. In 1739, [[James Oglethorpe]] agreed to supply some Cherokee villages with corn in exchange for defense against [[Kingdom of Spain (1700–1808)|Spain]]. In 1760, when the Cherokee challenged [[Kingdom of Great Britain (1707–1801)|British]] authority during the [[United States of America#Seven Years' War|Seven Years' War]], [[Jeffery Amherst]] ordered his troops to destroy Cherokee towns and kill civilians. The British burned 15 towns and made 5,000 people [[Homelessness|homeless]].<ref name=":0" /> | The Cherokee became suspicious of the [[Kingdom of England (927–1707)|English]] when [[Settler colonialism|settlers]] infected their towns with smallpox and alcohol. In 1739, [[James Oglethorpe]] agreed to supply some Cherokee villages with corn in exchange for defense against [[Kingdom of Spain (1700–1808)|Spain]]. In 1760, when the Cherokee challenged [[Kingdom of Great Britain (1707–1801)|British]] authority during the [[United States of America#Seven Years' War|Seven Years' War]], [[Jeffery Amherst]] ordered his troops to destroy Cherokee towns and kill civilians. The British burned 15 towns and made 5,000 people [[Homelessness|homeless]].<ref name=":0" /> | ||

| Line 13: | Line 14: | ||

==== Trail of Tears ==== | ==== Trail of Tears ==== | ||

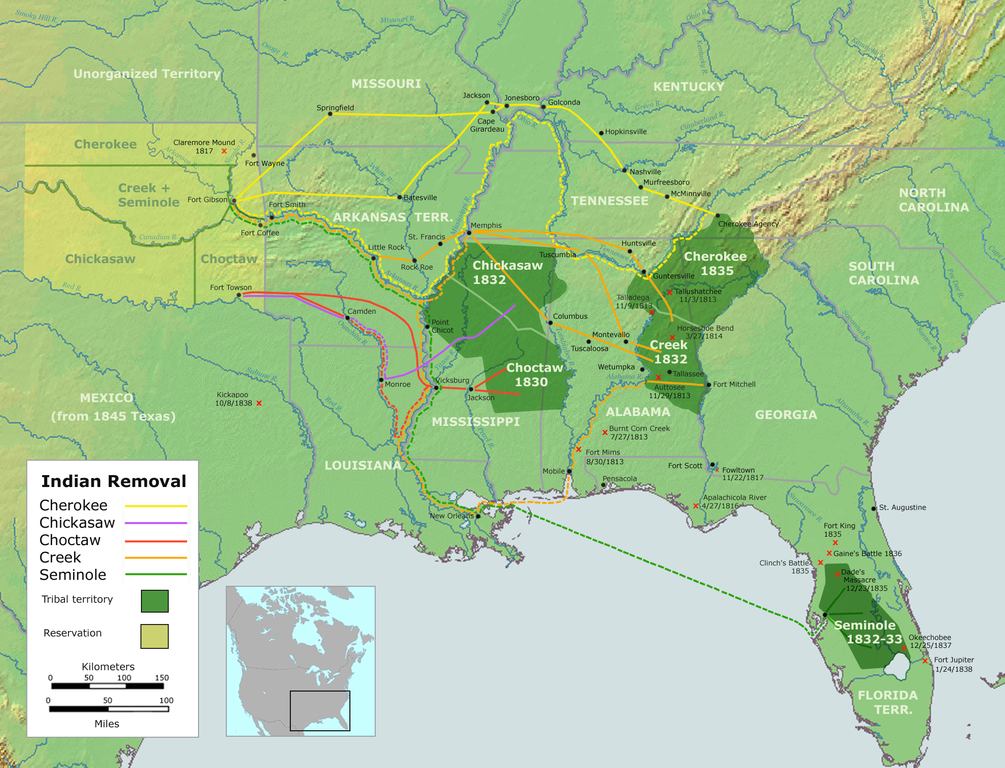

[[File:A map of the process of Indian Removal in the US, 1830–1838. Oklahoma is depicted in light yellow-green..png|thumb|Map of the Indian Removal Act, which exiled the Cherokee and four other nations to what is now Oklahoma]] | |||

After [[Andrew Jackson]]'s election in 1828, Georgia claimed most of the Cherokee's land. [[United States Congress|Congress]] passed the [[Indian Removal Act]] in 1830, which the [[Supreme Court of the United States|Supreme Court]] ruled unconstitutional. Some Cherokee moved to Indian Territory in [[State of Oklahoma|Oklahoma]] starting in 1832, and the [[United States Army|army]] forced the rest to move there in 1838, killing half of the 16,000 Cherokee along the way.<ref name=":04">{{Citation|author=[[Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz]]|year=2014|title=An Indigenous Peoples' History of the United States|chapter=The Last of the Mohicans and Andrew Jackson's White Republic|pdf=https://www.lcps.org/cms/lib/VA01000195/Centricity/Domain/10601/An%20Indigenous%20Peoples%20History%20of%20the%20United%20States%20Ortiz.pdf|city=Boston, Massachusetts|publisher=Beacon Press|isbn=9780807000403|page=109–113}}</ref> | After [[Andrew Jackson]]'s election in 1828, Georgia claimed most of the Cherokee's land. [[United States Congress|Congress]] passed the [[Indian Removal Act]] in 1830, which the [[Supreme Court of the United States|Supreme Court]] ruled unconstitutional. Some Cherokee moved to Indian Territory in [[State of Oklahoma|Oklahoma]] starting in 1832, and the [[United States Army|army]] forced the rest to move there in 1838, killing half of the 16,000 Cherokee along the way.<ref name=":04">{{Citation|author=[[Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz]]|year=2014|title=An Indigenous Peoples' History of the United States|chapter=The Last of the Mohicans and Andrew Jackson's White Republic|pdf=https://www.lcps.org/cms/lib/VA01000195/Centricity/Domain/10601/An%20Indigenous%20Peoples%20History%20of%20the%20United%20States%20Ortiz.pdf|city=Boston, Massachusetts|publisher=Beacon Press|isbn=9780807000403|page=109–113}}</ref> | ||

Latest revision as of 12:56, 15 October 2023

The Cherokee (ᏣᎳᎩ) are an indigenous nation occupied by the United States. They originally lived in what is now Georgia.[1]

History[edit | edit source]

Early contact with settlers[edit | edit source]

The Cherokee became suspicious of the English when settlers infected their towns with smallpox and alcohol. In 1739, James Oglethorpe agreed to supply some Cherokee villages with corn in exchange for defense against Spain. In 1760, when the Cherokee challenged British authority during the Seven Years' War, Jeffery Amherst ordered his troops to destroy Cherokee towns and kill civilians. The British burned 15 towns and made 5,000 people homeless.[1]

Statesian Revolution[edit | edit source]

During the Statesian Independence War, the British supplied Cherokee towns with money and weapons while separatist rebels threatened to destroy them. In response to settler raids, Cherokees destroyed settlements in the Carolinas. In the summer and fall of 1776, over 5,000 settlers invaded the Cherokee Nation. 700 men from the Virginia militia attacked again in 1780 and 1781.[2]

U.S. occupation[edit | edit source]

The 1785 Treaty of Hopewell restricted settlement west of the Blue Ridge Mountains but was not enforced. Tennessee became a state in 1796, leading to conflict with the Cherokee living its eastern part. John Sevier ordered an attack on resistant Cherokee towns in 1788 and killed 30 people. Secretary of War Henry Knox told settlers to continue expanding into native lands. In 1791, in order to end constant attacks, the Cherokee signed the Treaty of Holston, giving up much of their land in exchange for $100,000 a year from the federal government.[3]

Trail of Tears[edit | edit source]

After Andrew Jackson's election in 1828, Georgia claimed most of the Cherokee's land. Congress passed the Indian Removal Act in 1830, which the Supreme Court ruled unconstitutional. Some Cherokee moved to Indian Territory in Oklahoma starting in 1832, and the army forced the rest to move there in 1838, killing half of the 16,000 Cherokee along the way.[4]

Civil War[edit | edit source]

Chief John Ross initially tried to stay neutral during the Civil War but later signed a treaty with the Confederate States of America. While most Cherokees did not own slaves, the wealthy elite that controlled politics supported the Confederacy. Stand Watie became a Brigadier General in the Confederate army, but many other indigenous soldiers supported the Union.[5]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz (2014). An Indigenous Peoples' History of the United States: 'Bloody Footprints' (pp. 66–69). [PDF] Boston, Massachusetts: Beacon Press. ISBN 9780807000403

- ↑ Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz (2014). An Indigenous Peoples' History of the United States: 'Bloody Footprints' (pp. 74–76). [PDF] Boston, Massachusetts: Beacon Press. ISBN 9780807000403

- ↑ Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz (2014). An Indigenous Peoples' History of the United States: 'The Birth of a Nation' (pp. 87–89). [PDF] Boston, Massachusetts: Beacon Press. ISBN 9780807000403

- ↑ Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz (2014). An Indigenous Peoples' History of the United States: 'The Last of the Mohicans and Andrew Jackson's White Republic' (pp. 109–113). [PDF] Boston, Massachusetts: Beacon Press. ISBN 9780807000403

- ↑ Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz (2014). An Indigenous Peoples' History of the United States: '"Indian Country"' (pp. 134–135). [PDF] Boston, Massachusetts: Beacon Press. ISBN 9780807000403