More languages

More actions

No edit summary Tag: Visual edit |

No edit summary Tag: Visual edit |

||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

Molotov was born in the [[Vyatka Governorate (1796–1929)|Vyatka province]] in 1890. He joined the [[Bolsheviks|Bolshevik faction]] of the [[Russian Social Democratic Labor Party|RSDLP]] in 1906 at the age of 16, adopting the name Molotov (from ''molot'', meaning 'hammer' or 'mallet'). Molotov served as an editor for [[Pravda]]; he was arrested and exiled twice by the [[Russian Empire (1721–1917)|tsarist regime]] for agitation. He was a member of the [[Petrograd Military Revolutionary Committee]] which planned the [[Russian revolution of 1917|October Revolution]] of 1917.<ref>No author (1944-02-06).: "M. Molotov, Man Who 'Makes Do'". [[Sunday Sun|''Sunday Sun'']]. Retrieved 2024-01-10.</ref> | Molotov was born in the [[Vyatka Governorate (1796–1929)|Vyatka province]] in 1890. He joined the [[Bolsheviks|Bolshevik faction]] of the [[Russian Social Democratic Labor Party|RSDLP]] in 1906 at the age of 16, adopting the name Molotov (from ''molot'', meaning 'hammer' or 'mallet'). Molotov served as an editor for [[Pravda]]; he was arrested and exiled twice by the [[Russian Empire (1721–1917)|tsarist regime]] for agitation. He was a member of the [[Petrograd Military Revolutionary Committee]] which planned the [[Russian revolution of 1917|October Revolution]] of 1917.<ref>No author (1944-02-06).: "M. Molotov, Man Who 'Makes Do'". [[Sunday Sun|''Sunday Sun'']]. Retrieved 2024-01-10.</ref> | ||

Molotov quickly rose through the ranks of party bureaucracy during the [[interwar period]]. He was appointed [[People's Commissar of Foreign Affairs of the USSR|People's Commissar of Foreign Affairs]] in May 1939, replacing [[Maxim Litvinov]]. Following the failure of | Molotov quickly rose through the ranks of party bureaucracy during the [[interwar period]]. He was appointed [[People's Commissar of Foreign Affairs of the USSR|People's Commissar of Foreign Affairs]] in May 1939, replacing [[Maxim Litvinov]]. Following the failure of [[collective security]], Molotov completely revised Soviet foreign policy. Recognising that the USSR wasn't prepared to fight [[German Reich (1933–1945)|Nazi Germany]] and subscribing to [[Joseph Stalin|Stalin]]'s belief that the [[Western Allies|Western democracies]] were actively trying to provoke a war between Germany and the Soviet Union in order to weaken both nations,<ref><blockquote>Exposing the hullabaloo raised in the British, French and North American press about Germany’s ‘plans’ for the seizure of Soviet Ukraine, Comrade Stalin said:<blockquote>It looks as if the object of this suspicious hullabaloo was to incense the Soviet Union against Germany, to poison the atmosphere and to provoke a conflict with Germany without any visible grounds.</blockquote>As you see, Comrade Stalin hit the nail on the head when he exposed the machinations of West European politicians who were trying to set Germany and the Soviet Union at loggerheads.</blockquote>V.M. Molotov, "[https://www.marxists.org/archive/molotov/1940/peace.htm#s31081939 Speech Delivered on 31 August 1939]"</ref> he signed [[Treaty of Non-Aggression between Germany and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics|a non-aggression treaty with the Germans now known as the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact]]. The pact bought the Soviets twenty-two months of peace to prepare for [[Operation Barbarossa|the inevitable German invasion]], secured considerable territory as a buffer between the [[German Army (1935–1945)|German Army]] and [[Moscow]], laid the groundwork for future German–Soviet cooperation, and turned the tables on Britain and France. | ||

During the [[Second World War#Eastern Front|Great Patriotic War]], Molotov served as the Deputy Chairman of the five-man [[State Defence Committee]]. He also negotiated the [[Agreement Between the United Kingdom and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics|Anglo-Soviet Agreement]], [[United States of America|Statesian]] [[An Act to Promote the Defense of the United States|lend-lease]] to the Soviet Union, the [[Twenty-Year Mutual Assistance Agreement Between the United Kingdom and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics|Anglo-Soviet Treaty]], and the [[Franco-Soviet Treaty of Alliance and Mutual Aid|Franco-Soviet Alliance]], and was present at the [[Moscow Conferences|Moscow]], [[Tehran Conference|Tehran]], [[Yalta Conference|Yalta]], [[Potsdam Conference|Potsdam]], and [[San Francisco Conference|San Francisco Conferences]]. After the war, Molotov fiercely defended Soviet interests, denouncing the [[Marshall Plan]] as [[Imperialism|imperialist]] and | During the [[Second World War#Eastern Front|Great Patriotic War]], Molotov served as the Deputy Chairman of the five-man [[State Defence Committee]]. He also negotiated the [[Agreement Between the United Kingdom and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics|Anglo-Soviet Agreement]], [[United States of America|Statesian]] [[An Act to Promote the Defense of the United States|lend-lease]] to the Soviet Union, the [[Twenty-Year Mutual Assistance Agreement Between the United Kingdom and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics|Anglo-Soviet Treaty]], and the [[Franco-Soviet Treaty of Alliance and Mutual Aid|Franco-Soviet Alliance]], and was present at the [[Moscow Conferences|Moscow]], [[Tehran Conference|Tehran]], [[Yalta Conference|Yalta]], [[Potsdam Conference|Potsdam]], and [[San Francisco Conference|San Francisco Conferences]]. After the war, Molotov fiercely defended Soviet interests, denouncing the [[Marshall Plan]] as [[Imperialism|imperialist]] and putting forth his own [[Molotov Plan]]. Molotov was relieved of his post as [[Minister of Foreign Affairs of the USSR]] in 1949, [[Polina Zhemchuzhina|his wife]] was convicted of [[treason]], and he was openly criticised by Stalin in 1952.<ref>https://revolutionarydemocracy.org/rdv8n1/stalin.htm</ref> | ||

Following [[Death of Joseph Stalin|Stalin's death]] in March 1953, Molotov was reappointed Minister of Foreign Affairs by [[Georgy Malenkov]], who succeeded Stalin as Chairman of the Council Ministers. A [[triumvirate]] was established consisting of Malenkov, Molotov, and [[Minister of Internal Affairs of the USSR|Minister of Internal Affairs]] [[Lavrentiy Beria]]. Molotov suspected that Beria was | Following [[Death of Joseph Stalin|Stalin's death]] in March 1953, Molotov was reappointed Minister of Foreign Affairs by [[Georgy Malenkov]], who succeeded Stalin as Chairman of the Council Ministers. A [[triumvirate]] was established consisting of Malenkov, Molotov, and [[Minister of Internal Affairs of the USSR|Minister of Internal Affairs]] [[Lavrentiy Beria]]. Molotov suspected that Beria was responsible for Stalin's death<ref>Ludo Martens (1996). ''[[Library:Another View of Stalin|Another View of Stalin]]'': 'From Stalin to Khrushchev' (pp. 253–262). <small>[PDF]</small> Editions EPO. <small>ISBN 9782872620814</small></ref> and the triumvirate ended in June 1953 when [[Nikita Khrushchev]], with the support of Molotov, Malenkov, [[Lazar Kaganovich]], [[Kliment Voroshilov]], and [[Georgy Zhukov]] had Beria arrested, tried, and executed. Khrushchev continued consolidating his power in the following years, forcing Malenkov to resign from his post in 1955. | ||

Khrushchev denounced Stalin in his [[On the Cult of Personality and Its Consequences|"Secret Speech"]] to the [[20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union|20th Congress of the CPSU]], initiated a policy of [[de-Stalinisation]], and pursued [[peaceful coexistence]] with the [[Western Bloc]], all of which Molotov | Khrushchev denounced Stalin in his [[On the Cult of Personality and Its Consequences|"Secret Speech"]] to the [[20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union|20th Congress of the CPSU]], initiated a policy of [[de-Stalinisation]], and pursued [[peaceful coexistence]] with the [[Western Bloc]], all of which Molotov viciously opposed. For his dissent, he was dismissed from his post as Foreign Minister once more. In June 1957, [[Anti-Party Group|a group consisting of Molotov, Malenkov, Kaganovich, Voroshilov, and others]] attempted to [[Coup d'état|remove Khrushchev from power]]. Their [[Anti-revisionism|anti-revisionist]] group controlled seven of 11 seats on the [[Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union|Presidium]], but the [[Central Committee of the CPSU|Central Committee]] removed them from leadership positions.<ref name=":03">{{Citation|author=Roger Keeran, Thomas Kenny|year=2010|title=Socialism Betrayed: Behind the Collapse of the Soviet Union|chapter=Two Trends in Soviet Politics|page=27–32|pdf=https://ipfs.io/ipfs/bafykbzaceaj5ucph44bjwyhlhsbycckr3ts76zbucn2hbrea32tltcd4s5ekg?filename=Roger%20Keeran_%20Thomas%20Kenny%20-%20Socialism%20Betrayed_%20Behind%20the%20Collapse%20of%20the%20Soviet%20Union-iUniverse.com%20%282010%29.pdf|publisher=iUniverse.com|isbn=9781450241717}}</ref> Molotov was dismissed from most of his posts and sent to [[Mongolian People's Republic (1924–1992)|Mongolia]] as an [[Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary of the USSR to the Mongolian People's Republic|ambassador]]. He was removed from all his positions and expelled from the CPSU outright in 1962. | ||

Molotov was rehabilitated and allowed to rejoin the CPSU in 1984 under [[Konstantin Chernenko]]. He criticised the [[Revisionism|revisionist]] policies of Foreign Minister [[Eduard Shevardnadze]]<ref>{{Web citation|newspaper=[[In Defense of Communism]]|title=A story about Molotov's last days|date=2021-11-08|url=http://www.idcommunism.com/2021/11/a-story-about-molotovs-last-days.html|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220615002357/http://www.idcommunism.com/2021/11/a-story-about-molotovs-last-days.html|archive-date=2022-06-15|retrieved=2022-10-25}}</ref> and continued to defend both his actions as Foreign Minister and Stalin's actions until his death in 1986. Like most Soviet leaders, Molotov did not | Molotov was rehabilitated and allowed to rejoin the CPSU in 1984 under [[Konstantin Chernenko]]. He criticised the [[Revisionism|revisionist]] policies of Foreign Minister [[Eduard Shevardnadze]]<ref>{{Web citation|newspaper=[[In Defense of Communism]]|title=A story about Molotov's last days|date=2021-11-08|url=http://www.idcommunism.com/2021/11/a-story-about-molotovs-last-days.html|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220615002357/http://www.idcommunism.com/2021/11/a-story-about-molotovs-last-days.html|archive-date=2022-06-15|retrieved=2022-10-25}}</ref> and continued to defend both his own actions as Foreign Minister and Stalin's actions until his death in 1986. Like most Soviet leaders, Molotov did not write any memoirs. However, he was frequently interviewed by Russian biographer [[Felix Chuev]], who published their conversations in a book titled [[Library:Molotov Remembers|''Molotov Remembers: Inside Kremlin Politics'']] (1993). | ||

== References == | == References == | ||

Latest revision as of 18:54, 5 November 2024

Vyacheslav Molotov Вячеслав Молотов | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Vyacheslav Mikhailovich Skryabin 9 March 1890 Kukarka, Russian Empire |

| Died | 8 November 1986 (age 96) Moscow, RSFSR, Soviet Union |

| Nationality | Russian |

| Political orientation | Marxism-Leninism |

| Political party | RSDLP (1906–1918) CPSU (1918–1961) |

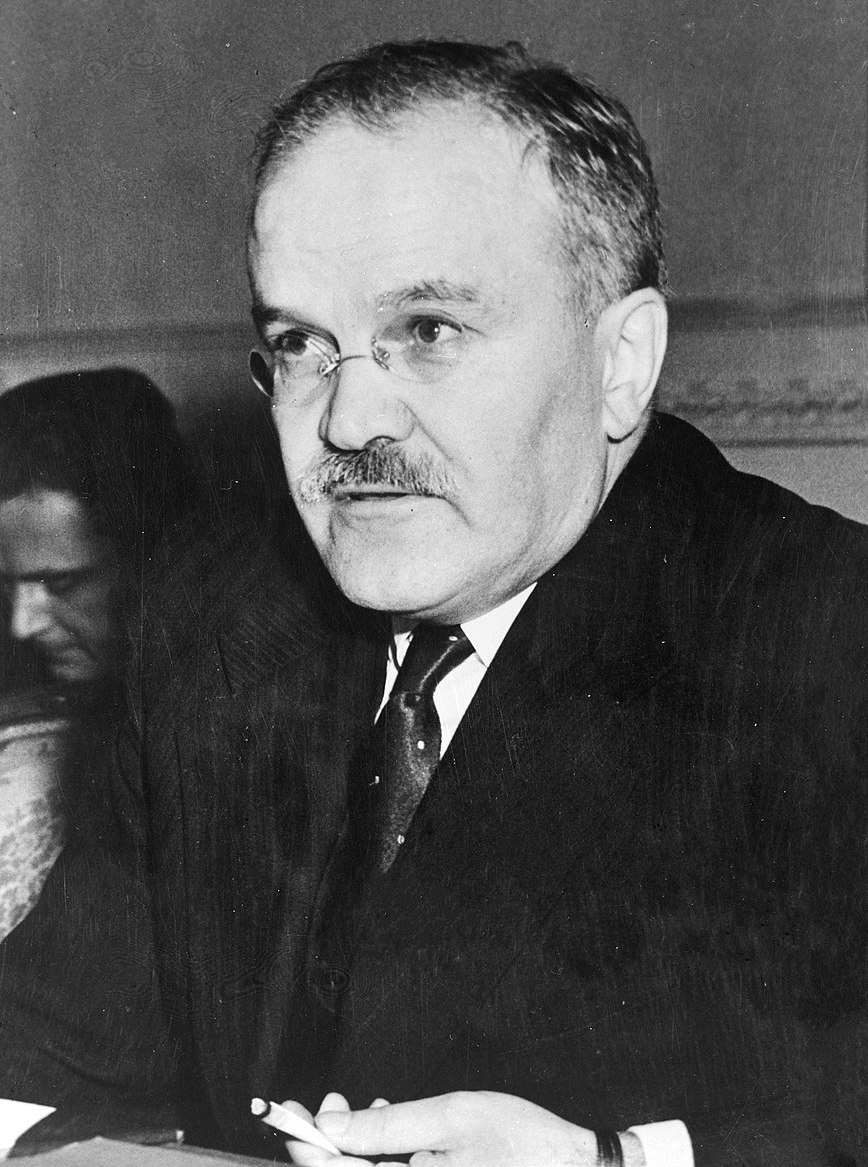

Vyacheslav Mikhailovich Molotov (born Skryabin; 9 March 1890 – 8 November 1986) was a Soviet revolutionary, diplomat, propagandist, and politician. He was the last-surviving major participant in the October Revolution at the time of his death in 1986.

Molotov was born in the Vyatka province in 1890. He joined the Bolshevik faction of the RSDLP in 1906 at the age of 16, adopting the name Molotov (from molot, meaning 'hammer' or 'mallet'). Molotov served as an editor for Pravda; he was arrested and exiled twice by the tsarist regime for agitation. He was a member of the Petrograd Military Revolutionary Committee which planned the October Revolution of 1917.[1]

Molotov quickly rose through the ranks of party bureaucracy during the interwar period. He was appointed People's Commissar of Foreign Affairs in May 1939, replacing Maxim Litvinov. Following the failure of collective security, Molotov completely revised Soviet foreign policy. Recognising that the USSR wasn't prepared to fight Nazi Germany and subscribing to Stalin's belief that the Western democracies were actively trying to provoke a war between Germany and the Soviet Union in order to weaken both nations,[2] he signed a non-aggression treaty with the Germans now known as the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact. The pact bought the Soviets twenty-two months of peace to prepare for the inevitable German invasion, secured considerable territory as a buffer between the German Army and Moscow, laid the groundwork for future German–Soviet cooperation, and turned the tables on Britain and France.

During the Great Patriotic War, Molotov served as the Deputy Chairman of the five-man State Defence Committee. He also negotiated the Anglo-Soviet Agreement, Statesian lend-lease to the Soviet Union, the Anglo-Soviet Treaty, and the Franco-Soviet Alliance, and was present at the Moscow, Tehran, Yalta, Potsdam, and San Francisco Conferences. After the war, Molotov fiercely defended Soviet interests, denouncing the Marshall Plan as imperialist and putting forth his own Molotov Plan. Molotov was relieved of his post as Minister of Foreign Affairs of the USSR in 1949, his wife was convicted of treason, and he was openly criticised by Stalin in 1952.[3]

Following Stalin's death in March 1953, Molotov was reappointed Minister of Foreign Affairs by Georgy Malenkov, who succeeded Stalin as Chairman of the Council Ministers. A triumvirate was established consisting of Malenkov, Molotov, and Minister of Internal Affairs Lavrentiy Beria. Molotov suspected that Beria was responsible for Stalin's death[4] and the triumvirate ended in June 1953 when Nikita Khrushchev, with the support of Molotov, Malenkov, Lazar Kaganovich, Kliment Voroshilov, and Georgy Zhukov had Beria arrested, tried, and executed. Khrushchev continued consolidating his power in the following years, forcing Malenkov to resign from his post in 1955.

Khrushchev denounced Stalin in his "Secret Speech" to the 20th Congress of the CPSU, initiated a policy of de-Stalinisation, and pursued peaceful coexistence with the Western Bloc, all of which Molotov viciously opposed. For his dissent, he was dismissed from his post as Foreign Minister once more. In June 1957, a group consisting of Molotov, Malenkov, Kaganovich, Voroshilov, and others attempted to remove Khrushchev from power. Their anti-revisionist group controlled seven of 11 seats on the Presidium, but the Central Committee removed them from leadership positions.[5] Molotov was dismissed from most of his posts and sent to Mongolia as an ambassador. He was removed from all his positions and expelled from the CPSU outright in 1962.

Molotov was rehabilitated and allowed to rejoin the CPSU in 1984 under Konstantin Chernenko. He criticised the revisionist policies of Foreign Minister Eduard Shevardnadze[6] and continued to defend both his own actions as Foreign Minister and Stalin's actions until his death in 1986. Like most Soviet leaders, Molotov did not write any memoirs. However, he was frequently interviewed by Russian biographer Felix Chuev, who published their conversations in a book titled Molotov Remembers: Inside Kremlin Politics (1993).

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ No author (1944-02-06).: "M. Molotov, Man Who 'Makes Do'". Sunday Sun. Retrieved 2024-01-10.

- ↑

V.M. Molotov, "Speech Delivered on 31 August 1939"Exposing the hullabaloo raised in the British, French and North American press about Germany’s ‘plans’ for the seizure of Soviet Ukraine, Comrade Stalin said:

It looks as if the object of this suspicious hullabaloo was to incense the Soviet Union against Germany, to poison the atmosphere and to provoke a conflict with Germany without any visible grounds.

As you see, Comrade Stalin hit the nail on the head when he exposed the machinations of West European politicians who were trying to set Germany and the Soviet Union at loggerheads.

- ↑ https://revolutionarydemocracy.org/rdv8n1/stalin.htm

- ↑ Ludo Martens (1996). Another View of Stalin: 'From Stalin to Khrushchev' (pp. 253–262). [PDF] Editions EPO. ISBN 9782872620814

- ↑ Roger Keeran, Thomas Kenny (2010). Socialism Betrayed: Behind the Collapse of the Soviet Union: 'Two Trends in Soviet Politics' (pp. 27–32). [PDF] iUniverse.com. ISBN 9781450241717

- ↑ "A story about Molotov's last days" (2021-11-08). In Defense of Communism. Archived from the original on 2022-06-15. Retrieved 2022-10-25.