More languages

More actions

| Roman Empire Imperium Rōmānum Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων | |

|---|---|

| 27 BCE–395 CE | |

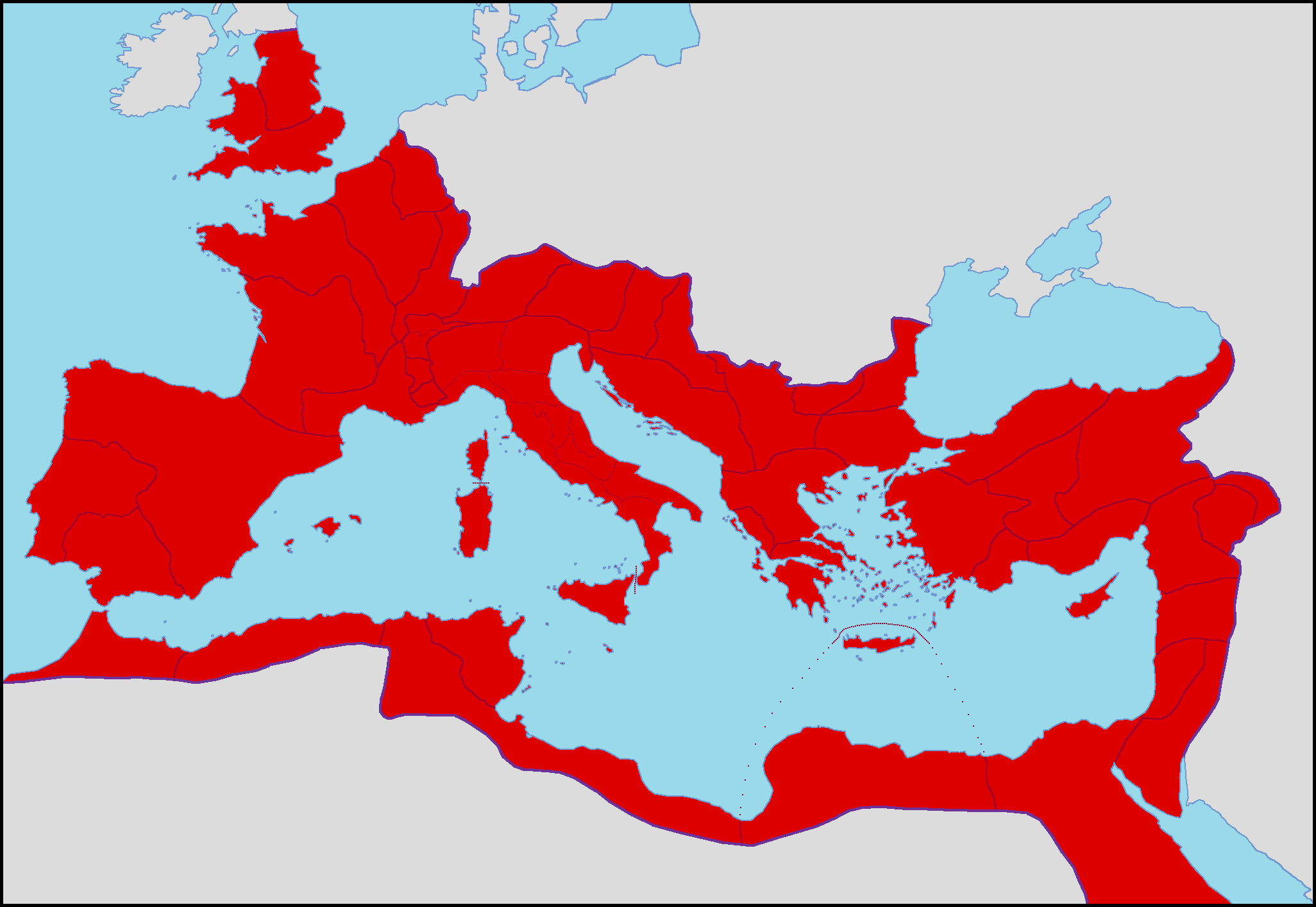

The Roman Empire in 280 | |

| Common languages | Latin Ancient Greek |

| Dominant mode of production | Slavery |

| History | |

• Empire established | 27 BCE |

• East-West division | 17 January 395 CE |

• Fall of Western Roman Empire | 4 September 476 |

| Area | |

• Total | 5,000,000 km²(117 CE) |

| Population | |

• 25 BCE estimate | 56,800,000 |

The Roman Empire was an ancient state that existed in Europe, West Asia, and North Africa. While the western part of the Roman Empire fell in 476 CE, the eastern part would live on for nearly a thousand more years, until 1453 CE.

History

Formation

The populist general Julius Caesar won the civil war of the Roman Republic in 45 BCE but was soon assassinated. Mark Antony and Octavian, the leaders of his faction defeated the pro-Senate opposition of Brutus and Cassius but then went to war against each other, with Octavian (renamed Augustus) becoming a military dictator and proclaiming himself the first emperor of Rome.[1]

Expansion

In 9 CE, Germanic tribes at Teutoborg defeated 30,000 Roman soldiers. Roman expansion slowed sharply after 50 CE and almost entirely ended by the late second century. Rome's last attempt to conquer northern Britain was defeated in 211 by guerrilla warfare. In 378, Goths destroyed the entire field army of the eastern empire in Thrace at the Battle of Adrianopole. The late empire became reliant on barbarian mercenaries from the same groups that Rome was fighting against.[2]

Decline and collapse

In the mid-fourth century, the Huns moved westward from the Eurasian steppe. They were skilled horse riders and archers and herded cattle, sheep, and goats. When they reached Eastern Europe, they overran the Ostrogoths and drove the Visigoths into the Roman Empire. The Huns forced Gothic peasants to pay tribute, which allowed them to strengthen their military. Attila became king of the Huns in 434 and attacked Gaul in 451. Celtic peasants sometimes joined forces with the Huns, but later joined with the landlords because of the Huns' predatory behavior, defeating Attila and sending him back to Eastern Europe where he died two years later.

Between 410 and 476, barbarians gradually took over parts of the Western Roman Empire until Western Europe was completely divided into various proto-states.[2]

Mode of production

Ancient Rome was a slave society that relied on war for its supply of slaves. The wealthy ruling class lived their whole lives without working and viewed their slaves as subhuman.[3] In the last two centuries of the empire, the slave mode of production began to decline. Population and production decreased and many large estates were broken into smaller ones. Slave owners freed many slaves because they could not profit from their labor and because many slaves intentionally destroyed or damaged the means of production. These people became small-scale producers called coloni, who later developed into the serfs of feudalism.

The Roman Empire was weakened by internal slave revolts and external invasions and eventually collapsed, ending slavery as the dominant mode of production in Europe.[4]

References

- ↑ Neil Faulkner (2013). A Marxist History of the World: From Neanderthals to Neoliberals: 'Ancient Empires' (p. 45). [PDF] Pluto Press. ISBN 9781849648639 [LG]

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Neil Faulkner (2013). A Marxist History of the World: From Neanderthals to Neoliberals: 'The End of Antiquity' (pp. 48–51). [PDF] Pluto Press. ISBN 9781849648639 [LG]

- ↑ Richard Becker (2008-05-29). "Ancient Greece and Rome: Democracy for the few, slavery for the many" Liberation School. Archived from the original on 2020-09-22. Retrieved 2022-08-27.

- ↑ Institute of Economics of the Academy of sciences of the USSR (1957). Political Economy: 'The Slave-Owning Mode of Production' (pp. 35–36). [PDF] London: Lawrence & Wishart.