More languages

More actions

| Republic of Zimbabwe Nyika yeZimbabwe Ilizwe leZimbabwe Dziko la Zimbabwe Nyika ye Zimbabwe Hango yeZimbabwe Zimbabwe Nù Inyika yeZimbabwe Nyika yeZimbabwe Tiko ra Zimbabwe Naha ya Zimbabwe Cisi ca Zimbabwe Shango ḽa Zimbabwe Ilizwe lase-Zimbabwe | |

|---|---|

Motto: Unity, Freedom, Work | |

| |

| Capital and largest city | Harare |

| Official languages | Chewa, Chibarwe, English (used in education, government, and commerce), Kalanga, Khoisan, Nambya, Ndau, Ndebele, Shangani, Shona, Zimbabwean sign language, Sotho, Tonga, Tswana, Venda, and Xhosa |

| Demonym(s) | Zimbabwean |

| Dominant mode of production | Capitalism |

| Government | Unitary presidential republic |

• President | Emmerson Mnangagwa |

• Vice-President | Constantino Chiwenga |

| History | |

| 11 November 1965 | |

| 2 March 1970 | |

| 1 June 1979 | |

| 18 April 1980 | |

| 15 May 2013 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 390,757 km² (60th) |

| Population | |

• 2022 estimate | 15,178,979[1] |

| Currency | Zimbabwean dollar United States dollar |

Zimbabwe, officially the Republic of Zimbabwe, is a landlocked country located in Southeast Africa. It is bordered by South Africa to the south, Botswana to the south-west, Zambia to the north, and Mozambique to the east.

The capital and largest city is Harare. Zimbabwe has been subjected to intense sanctions from imperialist powers, mainly in response to land reform policies that expropriated land from white settlers.[2]

The area that is now modern Zimbabwe was known during the British colonial period as Southern Rhodesia, named for imperialist businessman Cecil Rhodes, who made his fortune in consolidating diamond mines. In 1965, the colony renamed itself Rhodesia and broke from the United Kingdom with the express purpose of maintaining white rule.[3]

An article in Liberation News describes the western imperialist hostility toward Zimbabwe, saying: "hostility stems first and foremost from the fact that Zimbabwe's government has its origin in the armed struggle that ended the Western-backed racist, fascist settler regime. U.S. and British opposition to the government reached a crescendo as the Mugabe government moved to confiscate and redistribute the commercial agricultural land owned by white farmers. This land constituted 70 percent of the country’s prime farmlands."[2]

History

Early history

The country which is now known as Zimbabwe has been inhabited by many different peoples and kingdoms with complex relationships throughout history and was not a single geographical entity before its colonial occupation by the British.[4] As noted in an article on the Government of Zimbabwe website, "the political, social, and economic, relations of these groups were complex, dynamic, fluid and always changing. They were characterised by both conflict and co-operation." The region's history includes the rise and fall of several large and influential states as well as people living in smaller forms of social organization.[5]

The city of Great Zimbabwe existed from 1100 to 1500 CE and had a population of 20,000. It controlled over 100,000 km² of territory between the Zambezi and Limpopo rivers, and its economy relied on cattle, farming, and trade of ivory, copper, gold, and slaves.[6] Great Zimbabwe is also noted for its long-distance and regional trade, including trade with China, India, West Asia, East and West Africa, among other regional and inter-regional areas. Other notable states which emerged in pre-colonial Zimbabwe include the Mutapa State, the Rozvi State, the Torwa state, Rozvi states and the Ndebele state. An article on the Government of Zimbabwe's website notes that while these large and influential pre-colonial states of Zimbabwe are a source of pride, the majority of Zimbabweans lived in smaller units, with pre-colonial Zimbabwe societies mainly being farming communities and pastoralists. The article also notes that cattle were an important indicator of wealth and that gold mining was a seasonal activity conducted mainly in summer and winter.[5]

As explained on the Government of Zimbabwe's website, pre-colonial Zimbabwe was a multi-ethnic society inhabited by the Shangni/Tsonga in the south-eastern parts of the Zimbabwe plateau, the Venda in the south, the Tonga in the north, the Kalanga and Ndebele in the south-west, the Karanga in the southern parts of the plateau, the Zezuru and Korekore in the northern and central parts, and finally, the Manyika and Ndau in the east. The article notes that scholars have tended to lump these groups into two broad categories, the Ndebele and Shona, "largely because of their broadly similar languages, beliefs and institutions" and describes the term "Shona" as an anachronism that did not exist until the 19th century and which "conflates linguistic, cultural and political attributes of ethnically related people."[5]

Colonialism

Portuguese colonialism

During the 1500s, the Portuguese reached the Mutapa state and attempted to convert the royal family to Christianity. Though initially achieving some success, eventually the King renounced Christianity. The killing of a Portuguese missionary prompted punitive expeditions by the Portuguese, and they began interfering more in the region, demanding treaties of vassalage from a rival claimant of the Mutapa kingship and using slaves to work the land they acquired in these treaties (on estates known as prazos), resulting in many armed conflicts in the region. Eventually, the Portuguese were successfully driven out throughout the 1680s and 1690s, with Portuguese mercantilism no longer gaining a serious foothold in Zimbabwe.[5]

Europe's "Scramble for Africa"

After the expulsion of the Portuguese, internal regional affairs of Zimbabwe continued to unfold, while other effects of the European colonization of Africa led to changes throughout the continent, with the area that corresponds to present-day Zimbabwe becoming one of many points of geostrategic interest for the competing powers.

Over time, the Rozvi state encountered various difficulties, and eventually, came into conflict with Ndebele in the 1850s, resulting in the Ndebele state coming to prominence. According to South Africa History Online, by 1873 "the Ndebele was a consolidated state and at the height of their power."[4] The Government of Zimbabwe website describes this period in the following way, highlighting the interplay of the kingdom's own regional affairs as well as the increasing threat of instability posed by outside influences:

The Ndebele had to establish a strong military presence to establish their authority in their newly acquired land. Besides subduing the original Shona rulers, they had to content with the Boers from the Transvaal who in 1847 crossed the Limpopo and destroyed some Ndebele villages in the periphery of Ndebele country. Then there were the numerous hunters and adventurers who also entered the country to the south. Over and above these were the missionaries and traders; all these groups threatened the internal security and stability of the kingdom.[5]

By the late 1800s, the European colonizers were increasing their efforts to conquer Africa, and the "scramble for Africa" was formalized with the Berlin Conference of 1884-1885, with the formal partitioning of Africa to exploit its people and resources for colonial interests. The British thus began their incursions into the region later known as Zimbabwe in the 1880s.[4]

Among the European powers colonizing Africa, there were various competing designs for how to link up their own occupied areas into vast unbroken territories. British colonialist Cecil Rhodes, then active in business and politics in South Africa, was a proponent of expanding the British empire and of linking up British-occupied territory, a concept encapsulated in the vision of a "Cape to Cairo" railway. This vision would conflict with ideas such as Germany's aims of consolidating "Mittelafrika" which would span from the Atlantic to Indian Ocean, which, if realized, would block the north-south connection of Rhodes' plan. Given the geopolitical outlook of the time, Rhodes reasoned that the most viable path to his vision would be to seize the areas of Mashonaland and Matabeleland, then ruled by King Lobengula, an area which corresponds roughly to present-day Zimbabwe. In addition, Rhodes was drawn to this region by rumors of sources of gold.[7]

The Government of Zimbabwe website describes the role of missionaries in the colonization process as well:

[M]issionaries were the earliest representatives of the imperial world that eventually violently conquered the Shona and the Ndebele. They aimed as reconstructing the African world in name of God and Europe civilisation, but in the process facilitating the colonisation of Zimbabwe. [...] Missionaries were consistent and persistent in denigrating and castigating African cultural and religions beliefs/practices as pagan, demonic and evil.[5]

The article further notes that it was missionaries (such as Rev. Charles Helm)[7] who assisted Cecil Rhodes and his accomplice Charles Rudd in misrepresenting the contents of a document to King Lobengula, known as the Rudd Concession, inducing him to sign it under false pretenses, and thereby unintentionally ceding land and mineral rights to Rhodes. The article states that some positives did come from the missionaries, along with the abuses, and that in light of these ambiguities, the "African response to Christianity remained ambivalent."[5]

Rudd Concession

A so-called concession, known as the Rudd Concession, which Cecil Rhodes' delegation misrepresented to King Lobengula as they induced him to sign it, granted the company "the complete and exclusive charge over all metals and minerals" in the region, as well as "full power to do all things that they may deem necessary to win and procure the same," which the company used as permission to seize land.[8]

Following this, Lobengula learned what the actual contents of the document had been, and sent a letter to Queen Victoria explaining the deliberate deception and that he would not recognize the document as valid. An official response advised Lobengula that it would be "impossible" for him to exclude white men looking for gold in his land, along with giving advice on how to manage their presence there to give the "least trouble to himself and his tribe", and expressed the Queen's approval of Lobengula's so-called concession.[8][9]

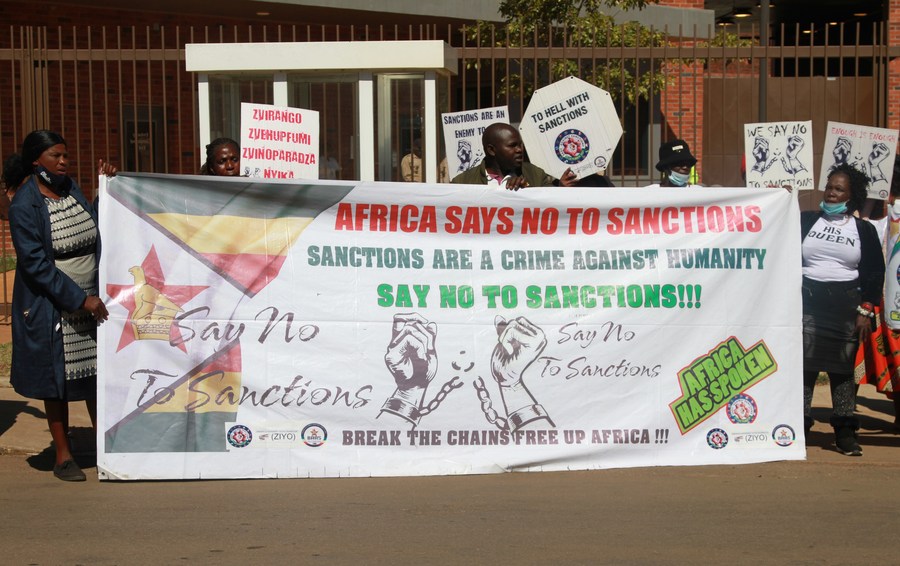

Sanctions

See also: Economic sanctions#Zimbabwe

According to Chidiebere C. Ogbonna in the African Research Review, from 1966 until the present, "Zimbabwe at one time or another has been under sanctions either by the United Nations the United States, the European Union or all the aforementioned. In total, Zimbabwe has been sanctioned in seven sanction-episodes: 1966, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2005, 2008 and 2009, making it one of the most sanctioned countries in the world." Ogbonna states that in a simple analysis, Zimbabwe has become a regular candidate of the "sanctions industry."[10]

According to a 2022 article by Xinhua News, the U.S. sanctions against Zimbabwe have accumulated since 2001, following a government decision to repossess land from minority white farmers for redistribution to landless indigenous Zimbabweans. The Xinhua article notes that though the Zimbabwean government said the land reform would promote democracy and the economy, "Western countries launched repeated sanctions with little regard for the average person's suffering." Linda Masarira, president of the Labour Economists and Afrikan Democrats (LEAD) political party, said sanctions have been used as a tool of economic warfare against Zimbabwe, and that sanctioning Zimbabwe "was an action that the United States of America decided to do on Zimbabwe to ensure that they make our economy scream, they make things hard for Zimbabweans and imply that black Zimbabweans, native Zimbabweans cannot do their own farming, or run their own economy."[11]

Economy

Zimbabwe has the largest lithium supply in Africa. In December 2022, the government banned raw lithium exports in order to process it into batteries in Zimbabwe.[12]

References

- ↑ https://zimbabwe.opendataforafrica.org/anjlptc/2022-population-housing-census-preliminary

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Covington, Arthur. “Zimbabwe’s People Reject Imperialist Intervention.” Liberation News. June 2005. Archived 2022-11-15.

- ↑ The New York Times. “Rhodesia’s Dead — but White Supremacists Have given It New Life Online (Published 2018)” Archived 2022-11-10.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 "Zimbabwe." South African History Online. Archived 2023-02-25.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 "History of Zimbabwe." About Zimbabwe, Official Government of Zimbabwe Web Portal. Archived 2024-04-12.

- ↑ Neil Faulkner (2013). A Marxist History of the World: From Neanderthals to Neoliberals: 'The First Class Societies' (p. 19). [PDF] Pluto Press. ISBN 9781849648639 [LG]

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Drohan, Madelaine. "Making a Killing: How and Why Corporations Use Armed Force to do Business." Ch. 1, Cecil Rhodes and the British South Africa Company. Random House Canada, 2003.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Elich, Gregory. "Zimbabwe Under Siege." August 26, 2002, GregoryElich.org. Archived 2024-04-13.

- ↑ "MOTION FOR ADJOURNMENT." HC Deb 09, November 1893, vol 18 cc543-627. UK Parliament. Archived 2022-08-11.

- ↑ Chidiebere C Ogbonna "Targeted or Restrictive: Impact of U.S. and EU Sanctions on Education and Healthcare of Zimbabweans." September 2017, African Research Review 11(3):31 DOI:10.4314/afrrev.v11i3.4

- ↑ Tichaona Chifamba, Zhang Yuliang, Cao Kai. "Two-decade-old U.S. sanctions leave Zimbabweans suffering, triggering protests". Xinhua. 2022-07-11. Archived 2022-09-09.

- ↑ Christopher Ojilere (2022-12-29). "Zimbabwe Bans All Lithium Exports" Voice of Nigeria. Archived from the original on 2022-12-30. Retrieved 2023-01-02.