More languages

More actions

| Republic of Zimbabwe Nyika yeZimbabwe Ilizwe leZimbabwe Dziko la Zimbabwe Nyika ye Zimbabwe Hango yeZimbabwe Zimbabwe Nù Inyika yeZimbabwe Nyika yeZimbabwe Tiko ra Zimbabwe Naha ya Zimbabwe Cisi ca Zimbabwe Shango ḽa Zimbabwe Ilizwe lase-Zimbabwe | |

|---|---|

Motto: Unity, Freedom, Work | |

| |

| Capital and largest city | Harare |

| Official languages | Chewa, Chibarwe, English (used in education, government, and commerce), Kalanga, Khoisan, Nambya, Ndau, Ndebele, Shangani, Shona, Zimbabwean sign language, Sotho, Tonga, Tswana, Venda, and Xhosa |

| Demonym(s) | Zimbabwean |

| Dominant mode of production | Capitalism |

| Government | Unitary presidential republic |

• President | Emmerson Mnangagwa |

• Vice-President | Constantino Chiwenga |

| History | |

| 11 November 1965 | |

| 2 March 1970 | |

| 1 June 1979 | |

| 18 April 1980 | |

| 15 May 2013 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 390,757 km² (60th) |

| Population | |

• 2022 estimate | 15,178,979[1] |

| Currency | Zimbabwean dollar (2019-2024) Zimbabwean ZiG (2024-current) United States dollar |

Zimbabwe, officially the Republic of Zimbabwe, is a landlocked country located in Southeast Africa. It is bordered by South Africa to the south, Botswana to the south-west, Zambia to the north, and Mozambique to the east. The capital and largest city is Harare.

Zimbabwe has been subjected to intense sanctions from imperialist powers, mainly in response to land reform policies that expropriated land from white settlers.[2]

The area that is now modern Zimbabwe was known during the British colonial period as Southern Rhodesia, named for imperialist businessman Cecil Rhodes. In 1965, the settler colony broke from the United Kingdom with the purpose of maintaining white minority rule.[3] The national liberation struggle against the settler regime greatly intensified in the 1970s period of the liberation war. Following this, a 1979 conference led to an agreement on a new constitution for an independent Zimbabwe, transitional governance, and a ceasefire,[4] followed by general elections in 1980 and independence on April 18, 1980.[5]

An article in Liberation News describes the western imperialist hostility toward Zimbabwe, saying: "hostility stems first and foremost from the fact that Zimbabwe's government has its origin in the armed struggle that ended the Western-backed racist, fascist settler regime. U.S. and British opposition to the government reached a crescendo as the Mugabe government moved to confiscate and redistribute the commercial agricultural land owned by white farmers. This land constituted 70 percent of the country’s prime farmlands."[2]

History[edit | edit source]

Early history[edit | edit source]

The country which is now known as Zimbabwe has been inhabited by many different peoples and kingdoms with complex relationships throughout history and was not a single geographical entity before its colonial occupation by the British.[6] As noted in an article on the Government of Zimbabwe website, "the political, social, and economic, relations of these groups were complex, dynamic, fluid and always changing. They were characterised by both conflict and co-operation." The region's history includes the rise and fall of several large and influential states as well as people living in smaller forms of social organization.[5]

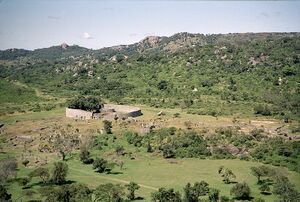

The city of Great Zimbabwe existed from 1100 to 1500 CE and had a population of 20,000. It controlled over 100,000 km² of territory between the Zambezi and Limpopo rivers, and its economy relied on cattle, farming, and trade of ivory, copper, gold, and slaves.[7] Great Zimbabwe is also noted for its long-distance and regional trade, including trade with China, India, West Asia, East and West Africa, among other regional and inter-regional areas. Other notable states which emerged in pre-colonial Zimbabwe include the Mutapa State, the Rozvi State, the Torwa state, Rozvi states and the Ndebele state. An article on the Government of Zimbabwe's website notes that while these large and influential pre-colonial states of Zimbabwe are a source of pride, the majority of Zimbabweans lived in smaller units, with pre-colonial Zimbabwe societies mainly being farming communities and pastoralists. The article also notes that cattle were an important indicator of wealth and that gold mining was a seasonal activity conducted mainly in summer and winter.[5]

As explained on the Government of Zimbabwe's website, pre-colonial Zimbabwe was a multi-ethnic society inhabited by the Shangni/Tsonga in the south-eastern parts of the Zimbabwe plateau, the Venda in the south, the Tonga in the north, the Kalanga and Ndebele in the south-west, the Karanga in the southern parts of the plateau, the Zezuru and Korekore in the northern and central parts, and finally, the Manyika and Ndau in the east. The article notes that scholars have tended to lump these groups into two broad categories, the Ndebele and Shona, "largely because of their broadly similar languages, beliefs and institutions" and describes the term "Shona" as an anachronism that did not exist until the 19th century, an exonym originally coined as an insult, and which "conflates linguistic, cultural and political attributes of ethnically related people."[5]

Portuguese colonialism[edit | edit source]

During the 1500s, the Portuguese reached the Mutapa state and attempted to convert the royal family to Christianity. Though initially achieving some success, eventually the King renounced Christianity. The killing of a Portuguese missionary prompted punitive expeditions by the Portuguese, and they began interfering more in the region, demanding treaties of vassalage from a rival claimant of the Mutapa kingship and using slaves to work the land they acquired in these treaties (on estates known as prazos), resulting in many armed conflicts in the region. Eventually, the Portuguese were successfully driven out throughout the 1680s and 1690s, with Portuguese mercantilism no longer gaining a serious foothold in Zimbabwe.[5]

Europe's "Scramble for Africa"[edit | edit source]

After the expulsion of the Portuguese, internal regional affairs of Zimbabwe continued to unfold, while other effects of the European colonization of Africa led to changes throughout the continent, with the area that corresponds to present-day Zimbabwe becoming one of many points of geostrategic interest for the competing powers.

Over time, the Rozvi state encountered various difficulties, and eventually, came into conflict with Ndebele in the 1850s, resulting in the Ndebele state coming to prominence. According to South Africa History Online, by 1873 "the Ndebele was a consolidated state and at the height of their power."[6] The Government of Zimbabwe website describes this period in the following way, highlighting the interplay of the kingdom's own regional affairs as well as the increasing threat of instability posed by outside influences:

The Ndebele had to establish a strong military presence to establish their authority in their newly acquired land. Besides subduing the original Shona rulers, they had to content with the Boers from the Transvaal who in 1847 crossed the Limpopo and destroyed some Ndebele villages in the periphery of Ndebele country. Then there were the numerous hunters and adventurers who also entered the country to the south. Over and above these were the missionaries and traders; all these groups threatened the internal security and stability of the kingdom.[5]

By the late 1800s, the European colonizers were increasing their efforts to conquer Africa, and the "scramble for Africa" was formalized with the Berlin Conference of 1884-1885, with the formal partitioning of Africa to exploit its people and resources for colonial interests. The British thus began their incursions into the region later known as Zimbabwe in the 1880s.[6]

Among the European powers colonizing Africa, there were various competing designs for how to link up their own occupied areas into vast unbroken territories. British colonialist Cecil Rhodes, then active in business and politics in South Africa, was a proponent of expanding the British empire and of linking up British-occupied territory, a concept encapsulated in the vision of a "Cape to Cairo" railway. This vision would conflict with ideas such as Germany's aims of consolidating "Mittelafrika" which would span from the Atlantic to Indian Ocean, which, if realized, would block the north-south connection of Rhodes' plan. Given the geopolitical outlook of the time, Rhodes reasoned that the most viable path to his vision would be to seize the areas of Mashonaland and Matabeleland, then ruled by King Lobengula, an area which corresponds roughly to present-day Zimbabwe. In addition, Rhodes was drawn to this region by rumors of sources of gold.[8]

The Government of Zimbabwe website describes the role of missionaries in the colonization process as well:

[M]issionaries were the earliest representatives of the imperial world that eventually violently conquered the Shona and the Ndebele. They aimed as reconstructing the African world in name of God and Europe civilisation, but in the process facilitating the colonisation of Zimbabwe. [...] Missionaries were consistent and persistent in denigrating and castigating African cultural and religions beliefs/practices as pagan, demonic and evil.[5]

The article further notes that it was missionaries (such as Rev. Charles Helm)[8] who assisted Cecil Rhodes and his accomplice Charles Rudd in misrepresenting the contents of a document to King Lobengula, known as the Rudd Concession, inducing him to sign it under false pretenses, and thereby unintentionally ceding land and mineral rights to Rhodes. The article states that some positives did come from the missionaries, along with the abuses, and that in light of these ambiguities, the "African response to Christianity remained ambivalent."[5]

Rudd Concession[edit | edit source]

A so-called concession, known as the Rudd Concession, which Cecil Rhodes' delegation misrepresented to King Lobengula as they induced him to sign it, granted the company "the complete and exclusive charge over all metals and minerals" in the region, as well as "full power to do all things that they may deem necessary to win and procure the same," which the company used as permission to seize land and obtain a royal charter (which was granted in 1889).[9][10]

Following this, Lobengula learned what the actual contents of the document had been, and sent a letter to Queen Victoria explaining the deliberate deception and that he would not recognize the document as valid. An official response advised Lobengula that it would be "impossible" for him to exclude white men looking for gold in his land, along with giving advice on how to manage their presence there to give the "least trouble to himself and his tribe", and expressed the Queen's approval of Lobengula's so-called concession.[9][11]

Settlers seize the land[edit | edit source]

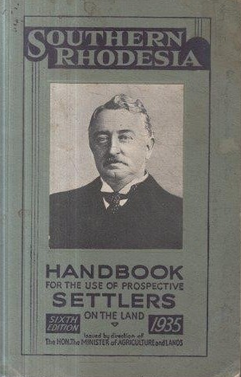

The British South African Company (BSAC) sought to produce a profit for its founder, Cecil Rhodes, and its other investors, in addition to expanding the British empire. Thus they sought to colonize the region, which they called "Southern Rhodesia", and which they believed to be rich in gold and other valuable minerals. However, the company itself was not interested in prospecting and mining the minerals themselves, but rather sought to profit through taxation, by enticing European settlers to move to Southern Rhodesia to do the prospecting and mining, with BSAC receiving royalties on all mined minerals:

To attract European settlers the BSAC publicized reports of the potential mineral wealth of Zimbabwe and promised each settler 15 mining claims and large tracks of land (3,175 acres per settler) on which to prospect for minerals. Minerals found and mined by the settlers would belong to them, but they would have to have to pay royalties (taxes) to the Company on all mined minerals.[12]

In addition, BSAC assembled the "Pioneer Column" to occupy the region and establish company rule, again recruiting these settlers with land offers. As the Government of Zimbabwe website summarizes:

In 1890, Rhodes unleashed the Pioneer Column to invade Mashonaland, marking the beginning of white settler occupation of Zimbabwe. The Shona were not quick to respond to the invasion as they wrongly assumed the column was merely a uniquely large trade and gold-seeking party that would soon vacate. Soon Rhodes’ invading British South Africa Company (BSAC) established a Native Department that authorised labour and tax raids on the Shona. Henceforth, constant skirmishes between Shona communities and tax collectors and labour raiders ensued as the Shona, who had not been conquered at all, saw no premise upon which the company could demand tax and labour from them. More significantly, however, the company started appropriating and granting land to the settler pioneers.[5]

After the formation of Southern Rhodesia, the settlers failed to find the large gold and mineral deposits they had expected to profit from. Both BSAC and the settlers were desperate to find alternative sources of income and wealth, and looked to agricultural production as their alternative, leading them to pursue further territorial expansion.[12]

Seeking dominance over the land, in October 1893, British troops and volunteers crossed into King Lobengula's territory of Matabeleland. As noted by author Gregory Elich, "the entire region rapidly fell into their hands as they inflicted heavy casualties on the Ndebele. Under terms of the resulting Victoria Agreement, each volunteer was entitled to 6,000 acres of land. Rather than an organized division of land, there was instead a mad race to grab the best land," with 10,000 square miles of the most fertile land being seized from its inhabitants within the first year. White settlers also confiscated most of the Ndebele's cattle, Elich notes, "a devastating loss to a cattle-ranching society such as the Ndebele."[9]

The settlers, who were relatively few in number yet had seized large tracts of land in their violent acts of primitive accumulation, now required people to work the land, and thus "the Ndebele became forced laborers on the land they once owned, essentially treated as slaves."[9] The Shona were also robbed of their cattle, as well as subjected to onerous taxes and forced labor, and local women were faced with sexual violence.[5]

The Government of Zimbabwe website explains that despite spirited resistance at the Battles of Mbembezi River, Shangani River and at Pupu across the Shangani River, the Ndebele were defeated in October 1893, leading Lobengula to set fire to his capital and flee to the north, never to be seen again, dead or alive. However, some Ndebele forces remained and would later rise up again against the colonizers. Likewise, the Shona would also rise up in the face of the colonizing forces. These uprisings, which occurred in 1896, are termed the First Chimurenga, and formed the basis of later mass nationalism and inspiration during the Second Chimurenga in the mid-1960s.[5]

Early colonial rule[edit | edit source]

Native Reserves[edit | edit source]

In 1894, the first of seven Land Commissions was established by the colonial regime. The colonizers soon established two reserves (in the arid locations of Gwai and Shangani) to which the Ndebele would be expelled, so as to protect the settlers while they stole the Ndebele's land, and to free up more attractive lands for the settlers while forcing the indigenous inhabitants into less desirable locations. In the following years, more "Native Reserves" (later called "Tribal Trust Lands") were created to expel Ndebele and Shona people to as the settler project proceeded with taking over the more fertile lands.[12]

Undermining indigenous agricultural production[edit | edit source]

As noted by the Government of Zimbabwe's history article, an early challenge for the colonial regime "was how to rule the Shona and Ndebele in an exploitative way, but without provoking another uprising." The article notes that land dispossession and forced proletarianization helped to secure the key aim of "maximum output premised on minimum cost", and was achieved through "restricting African access to land, thus undercutting African peasant agricultural production, increasing taxation and hence forcing Africans to sell their labour cheaply to white mine owners and farmers."[5]

Historian Alois S. Mlambo explains that in the early years, the settlers and colonial economy depended almost entirely on African labor and that the shortage of African labor was a "perennial problem" for the regime, resulting in part from the indigenous population's reluctance to work for a wage when they could meet most of their needs through independent agriculture and the sale of their produce to the settler population. Due to this state of affairs, white farmers and miners continually demanded that the state pass measures to force Africans into the labor market.[13]

South Africa History Online describes the process and methods in the following way:

Land was taken away from Africans and heavy taxes imposed as a way of forcing them into wage labour. As small scale farmers the African people in Rhodesia were self sufficient and had no need for seeking wage labour in the white cities. Yet the settlers needed cheap labour to work in mines, farms and factories around the colony. By taking away land and imposing what is called a “hut-tax” local people were forced to get jobs in the colonial economy. There were also put into place laws which forced Shona and Ndebele people to sign long-term contracts which forced them to stay in labour compounds. The result of these laws were that black people become slave labour in the white economy.[6]

The early period of the colonial regime was still focused largely on mining, though over time, the focus began to shift to agriculture as it became more apparent that the rumored massive gold reserves BSAC expected were not to be found. In this period, the settlers' mines and emerging towns obtained agricultural products primarily from indigenous peasant farmers, with settlers engaging in relatively minor agricultural activity themselves. As the settlers' agricultural sector gradually grew (as they were expelling the indigenous population to arid reserves, stealing their land, and otherwise restricting native people from land access), competition from African farmers still left white farming ventures in a precarious position. By 1908, a "white agriculture policy" was put forth by the colonial regime to boost the viability of white farmers who had previously been dependent on indigenous farmers:

Until white agriculture became established, however, the expansion of peasant production was allowed, as the settler community depended on it. This was soon to change as white commercial agriculture developed as a result of a vigorous state policy and a concerted campaign to promote white agriculture which was based on a multi-pronged white agriculture policy. This began with the creation of an Estates Department in 1908 to promote European settlement and to handle all applications for land.[13]

The government campaign to promote white agriculture included free agricultural training for white farmers; the establishment of a Land Bank to provide white farmers with loans for the purchase of farms, livestock, and equipment and for farm improvements such as irrigation and fencing; other inputs were offered at subsidized prices; and infrastructural projects were undertaken to improve the roads and irrigation near white settlements.[13] White farmers also benefitted by legislation such as the 1934 Maize Control Act which instituted two different prices for maize, with European farmers being paid a governmental guaranteed price for their maize that African farmers were not eligible for, instead having to sell on the open market with no price support. Meanwhile, the Cattle Levy Act placed a special tax on each head of cattle sold by African farmers, a tax from which European farmers were exempt.[12]

While white settlers were being aided by these policies, indigenous Zimbabweans continued to have their land stolen and be expelled to arid reserves, and indigenous farmers thus came under increasing pressure. By the 1930s, Africans were not allowed to own land outside the reserves, and most reserves were severely overcrowded with few employment opportunities for landless Zimbabweans.[9] Alois S. Mlambo notes that the reserves to which Africans were sent were not only poor agricultural land, but also far away from major transportation lines and market towns, further contributing to eliminating African competition in the market.[13] As the Government of Zimbabwe's website summarizes, "White commercial production was promoted on the back of the destruction of African peasant production. This wanton undercutting of African peasant production marked the beginning of the underdevelopment of African reserves in Rhodesia and the forcible proletarianisation of the African."[5]

Indigenous responses to settler regime[edit | edit source]

The various responses by indigenous Zimbabweans to the settler regime ranged from "outright resistance and acquiescence to adopting and adapting Christian ideologies and use of petitions for the return of Ndebele land alienated by the settlers."[5] By 1923, there was the Southern Rhodesia Bantu Voters Association, which though "largely an elitist organisation" is noted for its "vibrant Women’s league". Also significant was "the formation of African churches that broke away from the orthodox Christian churches to ameliorate the impact of colonialism" and the Industrial and Commercial Workers' Union (ICU)[5] which was active in several countries in Southern Africa.[14] Clements Kadalie, founder of the ICU, described how working and witnessing conditions in Southern Rhodesia had influenced him: "I had worked as a clerk in two leading mines in Southern Rhodesia, where I watched the evils of the recruiting system [...] it was the systematic torture of the African people in Southern Rhodesia that kindled the spirit of revolt in me."[15]

Native Registration Act and Native Pass Act[edit | edit source]

In an effort to control the movement of Zimbabweans, two acts of legislation were passed in 1935 and 1936, namely the 1935 Native Registration Act and the 1936 Native Pass Act. Together, these acts required all Zimbabwean Africans to be assigned and registered to a Tribal Trust Land (or TTL, and previously known as Native Reserves), even if they had never lived there before.[12] Every adult African (initially men and teenage boys, but later including women)[16] was issued and required to carry a registration book containing their identification information including their assigned TTL. Adults were required to have permission in the form of a written and stamped pass from the local district officer any time they left their assigned TTL, and if they were caught without their passes they could be arrested and sent back to their assigned TTL.[12]

The pass system included certificates known as situpas[17] (or chitupa, plural zvitupa)[18] issued to African men and boys (women were eventually included in 1976), as well as various types of passes, served as a method to control the mobility of the African population, restricting their entry into "white areas,"[19] subjecting Africans to daily harassment for documents and humiliating and time-consuming processes,[20][21] and included numerous details which could easily be used to limit the holder's physical movement, legal status, and economic options. The numerous required documents included such details as the pass holder's name, date of birth, home area, chief's name, name and location of last employer, previous wages, whether the worker had the employer's consent to leave the job, the employer's comments on the holder's character or work record, and tax payment records. Instances of desertion, trespassing and evading tax or medical obligations were all readily apparent on the passes, enabling easy criminalization of the card holding population, increasing the state's resource base via the imposition of fines and prison labor in addition to the pass system's overall function of maximizing the control of capital and the state over the indigenous population's movement and livelihoods.[16]

An article in African Studies Review notes that until 1976, African women were not subjected to the extensive pass system, but nonetheless faced certain travel and residence restrictions, experienced routine state harassment via frequent arrests and fines, and had the same legal status as children for their whole lives, regardless of education, finances, or marital status, effectively having no recourse to the law or managing finances or property ownership in their own right. The article also notes that the colonial authorities expressed wariness over issuing passes to women, having observed popular unrest and organized resistance to the issue in neighboring South Africa (although indigenous South African women eventually were subjected to the pass system in the 1950s), and wished to avoid such troubles, though the issue continued to be debated. The gendered disparity in the pass system provoked contention and dissatisfaction among various segments of Southern Rhodesia's population and administration. However, according to the analysis made by Teresa Barnes in African Studies Review, ultimately, "the underlying structural reason for the exclusion of women from the comprehensive pass law system was the relative underdevelopment of the Southern Rhodesian economy ... manifested in certain weaknesses in the state apparatus." Although the state did not implement the pass system for women until the 1970s, as the urban population of African women increased, "the state adopted a policy of low-intensity harassment of urban African women" via frequent arrests and fines, especially directed at unmarried women and women deemed to be "travelling prostitutes". The analysis also notes that African women were "tolerated" in urban and mining areas, as they were thought of as a useful sexual outlet and for keeping down incidences of the so-called "black peril", that is, white settlers' proclaimed fear of sexual assault of white women by black men, described in the article as "one of the great phobias of settler culture."[16]

Impacts and aftermath of Second World War[edit | edit source]

During the Second World War, thousands of Africans from Southern Rhodesia actively participated in the fighting, while others were involved in the production of food and minerals for the war effort. The period during the war and the immediate years after saw various political, social, and economic changes as African nationalist consciousness shifted away from reformist tendencies,[5] the settler regime continued forced relocations of Africans and stealing their land and cattle to give to settlers (including land awarded to white servicemen returning from the war),[13] and significant demographic shifts and economic changes occurred in the population post-war.[5][13]

Shifts in political consciousness and activity[edit | edit source]

The Government of Zimbabwe's history article explains that the war resulted in a significant transformation of the political consciousness of Africans. According to the article, while fighting side by side with whites, Africans "came face to face with shortcomings of the white man which debunked the notions of white invincibility and superiority" as well as being "exposed to contemporary thoughts and ideas on self-determination and equality." Such experiences and observations during the war led to a shift away from requesting fairness and accommodation from white governance structures, and instead more toward seeking self-rule.[5]

This period also included notable agitation by trade unionists, such as a railway workers strike in 1945, and student strikes, as well as other protest movements expressed by the Southern Rhodesia Bantu Congress as the Southern Rhodesia African Native Congress, the Voters League, and the creation of the African Methodist Church.[5] A 1948 general strike in Bulawayo demanding better wages spread nationally within days.[22]

Mass confiscations and forced relocations[edit | edit source]

Also during this period, the colonial government took measures supposedly to address the degradation of land quality in the Tribal Trust Lands, by limiting the amount of livestock permitted on the land. This entailed pressuring and threatening Africans into selling their "surplus" cattle against their wishes and at low prices, with some cattle being "sold" without the owner's presence nor consent. The cattle were then "entrusted" to white settlers who were paid by the Cold Storage Commission to look after them, amounting to a mass transfer of Africans' cattle to white ownership.[13]

Despite being blamed on too much livestock and supposedly bad farming techniques, the degradation of the land was in actuality mainly due to overcrowding caused by the colonial policies of forcing people to live in reserves, such as in 1944 when the government forcibly removed thousands of Africans from their traditional home areas in order to open up more land to give as a reward to white servicemen after their time at the war front. However, environmental problems in the Native Reserves continued to be blamed on too many cattle and allegedly poor farming practices by Africans, rather than on the severe overcrowding caused by the forced relocations, providing a narrative for the settler regime to continue transferring cattle from Africans to whites.[13]

Other social and economic changes[edit | edit source]

Another impact of the war was the expansion of the manufacturing and industrial sector. This emerging sector demanded a larger urban-based labor force, prompting policies which further pushed over 100,000 Africans off of the land and into the cities.[5]

In the immediate post-war years, there was a large influx of white immigration, resulting in further displacement of African communities as well as fueling an increase in inter-racial tensions. Tensions also arose between the newer and older white settlers, who tended to hold somewhat different views on how best to administer the settler regime--that is, whether to maintain strict white rule or to make some concessions to avert the growth of militant African nationalism.[5]

The post-war era also saw the growth of an African middle class of educated professionals whose concerns and aspirations "initially tended to run counter to those of the ordinary masses."[5]

Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland[edit | edit source]

The Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland, also called the Central African Federation (CAF), was created in late 1953, via a referendum in which only 429 Africans were eligible to vote.[23] The federation lasted until December of 1963. The federation joined Southern Rhodesia with the British protectorates of Northern Rhodesia (Zambia) and Nyasaland (Malawi), with Salisbury (Harare) as the federal capital, and Godfrey Huggins as Prime Minister (who had been PM of Southern Rhodesia for 23 years). Various factors contributed to the federation's formation, including grievances of the European settlers in the region, an increased worldwide demand for copper (which could be found in Northern Rhodesia), along with worries of the British government about the rise of black African nationalists' demands for independence.[24]

Historian Alistair Boddy-Evans writes about the reasoning of white settlers which led to the debate over independence, rooting it in their frustration with British colonial laws, seeing British law as a barrier in their desire to gain greater control over the indigenous African workforce:

White European settlers in the region were perturbed about the increasing Black African population but had been stopped during the first half of the twentieth century from introducing more draconian rules and laws by the British Colonial Office. The end of World War II led to increased white immigration, especially in Southern Rhodesia, and there was a worldwide need for copper which existed in quantity in Northern Rhodesia. White settler leaders and industrialists once again called for a union of the three colonies to increase their potential and harness the Black workforce.[24]

A 1972 work by ZAPU summarized: "Basically, this Federation was to open a wider market for Southern Rhodesian goods; unite all the settler forces and create a bigger settler land in Central Africa" and noted that it was met with strong opposition by Africans throughout Zambia, Zimbabwe, and Malawi, stating that this "marked the beginning of coordinated active African politics in Central Africa."[25]:20

During the debates around the federation's formation, settler politician Ian Smith proposed that if the federation dissolved, Rhodesia would be given automatic independence. This was rejected in the Parliament debate,[26] but Smith would refer to the principle of this idea multiple times in his memoir as he described the reasoning of his later decision to unilaterally declare independence, for example stating his view that "if, in the end, the British did decide to appease the black extremists and renege on all their promises, then at least we Southern Rhodesians could fall back on our independence, which had been offered to us on many occasions and which had been the alternative to Federation."[27]

Describing the end of the federation period, Smith wrote of "ominous" changes in the attitude of the British government, which, in Smith's words, developed a "dreadful philosophy of appeasement" toward the "extravagant demands" of black politicians.[28]:37 Furthermore, he perceived a change in attitude toward colonialism, with the "well-known and tried policy of gradualism and evolution [...] rapidly fading into the background" under anti-colonial pressure.[27] According to Smith, following British PM Harold Macmillan's "Winds of Change" speech in 1960, "a sudden dramatic change in Britain’s colonial policy emerged, and the most outrageous thing of all was that it was not the Labour Party, but the Conservatives, our ‘trusted’ friends, who were the architects of the plan." Smith wrote that after this, and after a black majority was achieved in Nyasaland's legislative council, "the writing was on the wall" for the end of the federation.[28]:40 He also pointed to the chaotic situation in recently independent Congo further sparking settlers' fears of the potential sudden implementation of majority rule. These and other factors would influence Smith and others in the founding of the Rhodesian Front party in 1962.[28]:44

City Youth League[edit | edit source]

The growing tide of nationalist consciousness and mass action was reflected in events such as the formation of the City Youth League in 1955 by young activists such as George Nyandoro, James Chikerema, Edson Sithole and Duduza Chisiza. Their militancy was exemplified in the Salisbury Bus Boycott of 1956,[5] in which 200 nationalists were detained.[23]

Southern Rhodesian African National Congress[edit | edit source]

In 1957, the City Youth League merged with the Bulawayo-based African National Council (which had been formed by Aaron Jacha in 1934),[23] forming the first national political party, the Southern Rhodesian African National Congress (SRANC, later referred to as ANC), under Joshua Nkomo.[5] The ANC challenged unpopular colonial policies such as the forced destocking of cattle and the Land Husbandry Act of 1951, which included reducing the size of African land units, the number of cattle individuals could hold, and undermining chiefs' customary right of allocating land.[5][29]

Resistance to the Land Husbandry Act took the form boycotting any application process for special farming and grazing permits, with violent protests also emerging throughout the country, resulting in the declaration of a state of emergency in 1959, the banning of the ANC under the newly created Unlawful Organizations Act, confiscation of party assets, and the arrest of 500 members.[5][23][29] In his memoir, Ian Smith described figures such as Nkomo and Reverend Ndabaningi Sithole during their involvement with ANC as being "terrorist leaders" and was critical of Prime Minister Garfield Todd at the time, describing "his tendency to give priority to black political advancement at the expense of economic and material advancement" though he praised Todd for suppressing striking coal miners at Hwange in 1954.[30]

In a 1978 address to Mozambican journalists, ZANU leader Robert Mugabe made an analysis of the ANC's strategies and objectives at the time, referring to the ANC (along with NDP and ZAPU) as one of ZANU's "three elder brothers."[31] In his view, although its organizational effect was "good in some areas" the areas affected by the ANC's strategies were relatively few, and although various actions were organized, it was only for a limited period, and not widespread or lasting, therefore unable to achieve "overall mass action". Furthermore, Mugabe stated that although the ANC did engage in "some talk of majority rule" it "lacked clarity in its ultimate objective" and remained reformist, seeking remedial measures, as "the principle of power totally transferring to the people had not emerged in any concrete form." He states that in subsequent nationalist parties, the political objectives and the demands for political power to the people became clearer and took a more solid form, expressed through slogans such as "one-man-one-vote" and "majority rule now."[32]

National Democratic Party[edit | edit source]

Following the ban of the ANC, the increasingly militant nationalists formed the National Democratic Party (NDP) on January 1, 1960, initially under Michael Mawema, though Nkomo was elected NDP president later that year. The NDP made the landmark demand of majority rule under universal suffrage.[5] As protests continued to break out, the NDP was blamed for initiating riots and banned in 1961. The banning of the NDP further incensed the population, with protests continuing to disrupt the implementation of unpopular policies, leading to the Land Husbandry Act being "virtually abandoned" by the government in 1962.[29]

According to the analysis made by Mugabe, during this period, the older methods of non-collaboration were not discouraged, "but certainly not encouraged vigorously" except in the case of "strikes and demonstrations undertaken simultaneously in 1960 and 1961 respectively in the major urban centres." Mugabe explained the rationale of this change in emphasis, stating that the emphasis on single grievances had caused people to focus on superficial and temporary remedies, which "fell short of the necessary political awareness of the colonial situation." Therefore, mass rallies were held throughout the country in rural and urban centers in order to educate people toward acquiring power in order to change the system itself, leading to a surge in the masses' demands for one-man-one-vote.[33]

Zimbabwe African People's Union[edit | edit source]

The banning of the NDP led the nationalists to establish the Zimbabwe African People's Union (ZAPU) in December of 1961, again under Joshua Nkomo.[5]

Mugabe states that during this period, in addition to strikes, boycotts and demonstrations, there were also planned acts of sabotage, with petrol bombs first being used in 1960 and gelignite explosives by 1961, but mainly in 1962, to blow up targets such as commercial shops, factories, and petrol installations. Mugabe explains that by 1962, strikes were abandoned in favor of sabotage, as strikes were evaluated to have negative effects on the struggle by creating grievances against the Party resulting from dismissals and arrests. Therefore, "sabotage alone was thus resorted to in 1962 and factories burnt down, tobacco and cattle plantations were destroyed, and so was stock on settler farms." However, Mugabe notes that these actions "had no permanent effect as they lasted for a brief period only, nor were they comprehensive enough." Furthermore, during this period, he explains that "the strategy of the struggle was not to overthrow the enemy but to exert enough pressure on the British Government to cause constitutional change in the direction of majority rule or one-man-one-vote."[33]

Rhodesian Front[edit | edit source]

By March of 1962, the Rhodesian Front (RF) party was formed. ZAPU was banned in September of 1962, with RF later winning the December 1962 elections.[23] Author Masipula Sithole contextualized RF's 1962 victory within the shifting sentiments of the white settler population over time as reflected in their successive regimes, writing that "the 'liberal' regime of Garfield Todd had been replaced by the 'not-so liberal' regime of Edgar Whitehead, which, in turn, had been swept away in a rising tide of white right wing reaction resulting in the Rhodesia Front victory in the 1962 elections. White attitudes were hardening and the election was won on a white supremacy platform."[34]

In Sithole's view, the split in ZAPU which would occur in the following year must be seen with this rising tide of right wing reaction in the settler population and government as its context. Sithole writes:

Politics of petitions and constitution-demanding could have flourished generally during liberal or quasi-liberal regimes. But the Rhodesia of 1962 and beyond demanded different responses. Some among the nationalists saw this phenomenon, but others did not. Some saw it but were afraid, while others were not. Some accepted the challenge, but others could not. Some thought the situation called for cautious manipulation of the international environment, while others felt that direct action of a radical sort was the only option realistically left for resolving the problem.[34]

In Sithole's view, although there was a rising consciousness about the need for radical approaches to decolonization and desettlerization among the African nationalists, including among ZAPU leaders, in his evaluation, it is necessary to draw a distinction between those who could "see 'what needs to be done'" versus those who would "do what needs to be done" when seeking to understand the rifts that would develop in the nationalist movement.[34]

Zimbabwe African National Union[edit | edit source]

By August 8, 1963, Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU) was formed by former ZAPU members who were dissatisfied with Nkomo's leadership.[23] Initially ZANU was under the leadership of Ndabaningi Sithole.[5] ZANU aimed to leave behind the "pressure and leverage" strategy of former parties and instead embrace direct confrontation with the colonizer by means of armed struggle.[35]

According to a 1972 ZAPU document, ZAPU held a conference on August 10, 1963 in which it rejected the formation of a new party, regarding it as a violation of a previous decision to never form a new party as well as considering it to be playing into colonial divide-and-rule tactics. The conference resolved to expel Ndabaningi Sithole, Robert Mugabe, Washington Malianga and Leopold Takawira, describing them as "conspiring and plotting to side-step the People by forming a party as individuals and dividing the people of Zimbabwe" and "contemptuously breaking the pledge they themselves repeatedly made to the people". The resolution concluded by "expel[ling] them totally from being leaders of the African People of Zimbabwe".[25]:33-7

Speaking in 1978 on the formation ZANU, Mugabe stated:

The period followed the banning of ZAPU in 1962 and the election victory of the Rhodesia Front in December that year groped for a radical transformation in the nature and means of struggle. It was at this stage of adjustment in our struggle that contradictions emerged within the nationalist movement and those of us who believed in the total overthrow of the settler regime through armed violence formed ZANU in August 1963. At its inaugural Congress of May 1964, the Central Committee which had just been elected, was given a mandate to organise a programme of action against the settler regime. The Central Committee in compliance with the wish of Congress decided to organise armed struggle in its stages. The first was to be one of military training, but one also during which a series of violent action could be embarked upon. Hence the organisation of the Crocodile Group which operated in the Eastern part of the country and the Sabotage plan that operated, although ineffectively within the city of Salisbury and in other centres resulting in the blowing up of a railway locomotive in Fort Victoria.[36]

An article which was published in The Zimbabwe News in the late 1970s notes that the May 1964 congress also adopted the party statement of policy which espoused "some general principles of socialism" but that "the further stage of basing the Party’s socialist thought on the principles of scientific socialist principles had not yet been reached."[35]

ZANU was banned in 1964 and nationalist leaders detained.[23] In 1965, ZANU's Central Committee authorized those who had not been detained (due to being outside the country at the time) to form a Revolutionary Council (later known as DARE or Dare) under the chairmanship of Herbert Chitepo in order to carry on with the war to overthrow the settler regime.[36]

Unilateral Declaration of Independence[edit | edit source]

The Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI) of Rhodesia occurred on November 11, 1965 under the government of RF co-founder Ian Smith.[23]

Second Chimurenga[edit | edit source]

Zimbabwe's liberation war is known as the Second Chimurenga, the First Chimurenga being the uprisings waged against the colonizing forces in the 1890s.[23] The Shona word chimurenga carries various meanings such as uprising or revolution.[38][39]

Analyses of the Second Chimurenga sometimes break the war into two or three phases based on the tactics, activity level, and international relations of the liberation forces in a given period. The 1960s typically mark the first phase wherein the guerrillas engaged somewhat sporadically and lacked experience, while the early 1970s marks the second phase in which there was a change of tactics.[40] Analyses also note a period of attempted negotiations and detente from 1974-5[41] (which also resulted in notable prisoner releases of nationalist leaders including Joshua Nkomo, Robert Mugabe, and Ndabaningi Sithole),[42] and some mark the mid-to-late 1970s as a third phase.[43]

On April 28, 1966, in what is known as the battle of Chinhoyi,[44] a squad of seven guerrillas of the Zimbabwe African National Liberation Army (ZANLA), the military wing of ZANU, engaged in a twelve-hour battle with Rhodesian security forces which were backed by helicopter gunships, with the guerrillas eventually losing their lives in the battle. Although previous acts of resistance had occurred, the Chinhoyi battle is considered to be the first act of the armed struggle in Zimbabwe's liberation war.[23]

Another early series of engagements occurred in 1967, known as the Wankie Campaign, or "Operation Nickel" by the Rhodesian forces, in which an alliance of forces from ZAPU's Zimbabwe People's Revolutionary Army (ZIPRA) and the Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK) of South Africa's ANC were attempting to move undetected from Zambia to South Africa by traveling the outskirts of Hwange Game Reserve, but they were eventually detected by Rhodesian forces and fought in a number of armed clashes.[5][45]

On December 4, 1971, two ZANLA guerrillas, Justin Chauke and Amon Zindoga, crossed into northeastern Zimbabwe near Mukumbura, coming over from Mozambique's Tete Province, with the mission to begin laying the groundwork for protracted guerrilla warfare.[23]:2 A little over a year later, on December 21, 1972, a squad of nine ZANLA guerrillas attacked a settler-owned tobacco farm called Altena Farm, located in Mount Darwin in northeastern Zimbabwe.[23][46] This was the first settler farm to be attacked since 1966. At the time the farm was in the hands of a settler named Marc de Borchgrave who was a leading tobacco farmer, known for his poor labor relations. De Borchgrave and one of his children were lightly wounded in the attack. One white Rhodesian soldier was killed by a landmine, while five others were injured.[23]:2 An article in the news outlet The Patriot emphasizes that "A LOT of work had been going on behind the scenes before the opening of the north-eastern frontier of our war of liberation" and states that "by the time the first shots rang out at Altena Farm [...] everything was in place for ZANLA to operate from the north-eastern frontier" and analyzes this attack as "the precursor to other frontiers which would ultimately dismantle Rhodesian forces."[46] The authors of The Struggle for Zimbabwe evaluate that "this attack marked the change from the sporadic, and the militarily ineffectual, actions of the Sixties, to protracted armed struggle."[23]xvii

Economy[edit | edit source]

As a state which was afflicted with settler-colonialism and later successfully overcame the settler regime, while still having to contend with Western imperialism and neoliberal economic policies to this day, control over land and the economic distortions wrought by settler-colonialism have been key issues in Zimbabwe's economic development. Zimbabwe's present-day economic conditions must be considered in this context, with attention given both to Zimbabwe's local conditions as well as to Western imperialists' past and present efforts to hamper Zimbabwe's land redistribution process through methods such as unfavorable negotiations, dropped agreements, neoliberal structural adjustment programs, sanctions, and credit freezes.[47]

The Zimbabwe government's attempts to develop its economy and infrastructure through foreign investment have also been noted as a target for Western influence operations. At a US Embassy-funded "workshop" for journalism in 2021, US government officials bragged that they had sponsored media institutions to promote "accountability issues", as part of a strategy to discredit Chinese investment and encourage pro-Western sentiment in the country.[48]

Mining[edit | edit source]

Zimbabwe holds some of the world's largest platinum reserves and is Africa's top lithium producer,[49] having the largest lithium supply in Africa.[50] Mining Zimbabwe notes that since 2000, Zimbabwe's production has been dominated by the mining of gold, platinum, coal, nickel, chrome, diamonds, black granite, copper, silver, and asbestos.[51]

In December 2022, the government banned raw lithium exports in order to process it into batteries in Zimbabwe.[50] Zimbabwe took full control of Kuvimba Mining House (KMH) in 2024, with the company being 70% owned by Zimbabwe's sovereign wealth fund (Mutapa Investment Fund), and the remaining shares held by entities under the finance ministry. As of February 2025, it was reported that KMH is seeking $950 million from development banks, mining companies, and traders to fund lithium, platinum, and gold projects, such as building an underground platinum mine at the Darwendale project and a lithium project at Sandawana in partnership with Chinese mining firms.[49][52] It was reported in 2023 that KMH's Sandawana Mines aims to produce battery-grade lithium, processed within Zimbabwe, by 2030.[53]

An article in NewZWire noted that although one of the first major economic decisions of President Mnangagwa had made after assuming office in 2017 was to do away with the 51% local ownership rule for foreign investors in the "Open for Business" campaign which allowed 100% ownership, there has been a "gear shift" in line with the increasing trend of African economies shifting towards resource nationalism concerning their mineral resources, indicated in Zimbabwe by ideas such as discussion of a 26% free-carry government stake in new mining projects.[54] In December 2024, Zimbabwe's Secretary for Mines Pfungwa Kunaka discussed implementing a 26% free-carry stake for the Zimbabwe government in new mining projects, as well as negotiating with existing operators to acquire a similar stake. As of a 2024 report, Zimbabwe held a 15% free-carry stake in platinum miner Karo Resources.[55]

Agriculture[edit | edit source]

In regard to the common insinuation made by Western critics that indigenous Zimbabweans are incompetent farmers compared to the white settler commercial farm owners, land policy analyst Sam Moyo explained in a 2009 article that Zimbabwe's peasants and urban residents' gardens have always produced the majority of food consumed by the majority of Zimbabweans, while large white producers primarily produced for export, generally making products which the majority of the local population could not afford:

[C]lose to 70% of the food consumed by the 80% of Zimbabweans who are the working classes (peasants, formal and informal wage workers, the unemployed) and over 50% of the middle class foods, which comprise mainly grains (maize, sorghum, groundnuts and pulses as oils or for direct eating) and local relish (greens) have always been produced by the peasants and urban residents’ gardens. [...] by far the largest outputs (in volumes and value) produced by large farmers were destined for exports (tobacco, sugar, tea, coffee, horticulture, beef, etc.) and for the local industry (soaps, etc.). Although their exports were critical for forex (40% of national forex was from agriculture, but peasants produced 80% of the cotton and its attendant forex), they were not the main supplier of the food consumed by most of the population, who could not afford their products.[56]

Moyo states that there was a clear division of production between peasants and large farmers, with the peasants producing most of the cheaper and bulkier foods, and large farmers producing foods generally consumed by fewer people.

Addressing issues in the production of bulk foods such as maize, Moyo attributed it mainly to a decline in seed and fertilizer supply and reduced private and external financing. Extremely low input supplies (resulting from Western sanctions), combined with climate effects such as droughts and rain variability, reduced rain-fed maize production by the peasantry, as 90% of the irrigation resources were held by large farmers, including the sugar estates.[56]

Zimbabwe's Commercial Farmers' Union (CFU), known as the Rhodesian National Farmers' Union (RNFU) before 1980, was formed to represent the interests of commercial farmers, drawing its membership primarily from large scale and intensive commercial agricultural producers. It has its roots in the colonial period's Rhodesian Farmers' and Landowners' Association (RFLA) formed in 1892 by settler farmers looking to advance their interests.[57][58] A 2019 article published in The Patriot news outlet described CFU as a "historically-powerful white lobbying group"[59] which was one of the strongest advocates of Western-backed, World Bank and IMF-financed structural adjustment in the form of the 1990 Economic Structural Adjustment Policy (ESAP),[60] as well as being strongly opposed to Zimbabwe's land reforms.[59]

Sanctions[edit | edit source]

See also: Economic sanctions#Zimbabwe

According to Chidiebere C. Ogbonna in the African Research Review, from 1966 until the present, "Zimbabwe at one time or another has been under sanctions either by the United Nations the United States, the European Union or all the aforementioned. In total, Zimbabwe has been sanctioned in seven sanction-episodes: 1966, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2005, 2008 and 2009, making it one of the most sanctioned countries in the world." Ogbonna states that in a simple analysis, Zimbabwe has become a regular candidate of the "sanctions industry."[61]

According to a 2022 article by Xinhua News, the U.S. sanctions against Zimbabwe have accumulated since 2001, following a government decision to repossess land from minority white farmers for redistribution to landless indigenous Zimbabweans. The Xinhua article notes that though the Zimbabwean government said the land reform would promote democracy and the economy, "Western countries launched repeated sanctions with little regard for the average person's suffering." Linda Masarira, president of the Labour Economists and Afrikan Democrats (LEAD) political party, said sanctions have been used as a tool of economic warfare against Zimbabwe, and that sanctioning Zimbabwe "was an action that the United States of America decided to do on Zimbabwe to ensure that they make our economy scream, they make things hard for Zimbabweans and imply that black Zimbabweans, native Zimbabweans cannot do their own farming, or run their own economy."[62]

Further reading[edit | edit source]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ https://zimbabwe.opendataforafrica.org/anjlptc/2022-population-housing-census-preliminary

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Covington, Arthur. “Zimbabwe’s People Reject Imperialist Intervention.” Liberation News. June 2005. Archived 2022-11-15.

- ↑ The New York Times. “Rhodesia’s Dead — but White Supremacists Have given It New Life Online (Published 2018)” Archived 2022-11-10.

- ↑ Chirenje, J. Mutero. "A history of Zimbabwe for primary schools." Longman Zimbabwe, Harare, 1982.

- ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 5.11 5.12 5.13 5.14 5.15 5.16 5.17 5.18 5.19 5.20 5.21 5.22 5.23 5.24 5.25 5.26 5.27 5.28 5.29 "History of Zimbabwe." About Zimbabwe, Official Government of Zimbabwe Web Portal. Archived 2024-04-12.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 "Zimbabwe." South African History Online. Archived 2023-02-25.

- ↑ Neil Faulkner (2013). A Marxist History of the World: From Neanderthals to Neoliberals: 'The First Class Societies' (p. 19). [PDF] Pluto Press. ISBN 9781849648639 [LG]

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Drohan, Madelaine. "Making a Killing: How and Why Corporations Use Armed Force to do Business." Ch. 1, Cecil Rhodes and the British South Africa Company. Random House Canada, 2003.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 Elich, Gregory. "Zimbabwe Under Siege." August 26, 2002, GregoryElich.org. Archived 2024-04-13.

- ↑ "Rudd Concession by King Lobengula of Matabeleland (1888)." South African History Online. Archived 2024-02-03.

- ↑ "MOTION FOR ADJOURNMENT." HC Deb 09, November 1893, vol 18 cc543-627. UK Parliament. Archived 2022-08-11.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 "The Land Question." Module Thirty, Activity Three. Exploring Africa, Michigan State University African Studies Center. Archived 2024-04-13.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 13.5 13.6 13.7 Mlambo, Alois S. "A History of Zimbabwe." Cambridge University Press, 2014.

- ↑ "A Brief History of South Africa’s Industrial and Commercial Workers’ Union (1919-1931)." Dossier #20, The Tricontinental. September 3, 2019. (PDF). Archived 2024-04-21.

- ↑ Kadalie, Clements. "My life and the ICU: The Autobiography of a Black Trade Unionist in South Africa." Frank Cass & Co., Ltd., 1970.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Teresa Barnes (1997). "Am I a Man?": Gender and the Pass Laws in Urban Colonial Zimbabwe, 1930-80, vol. Vol. 40, No. 1. African Studies Review. doi: 10.2307/525033 [HUB]

- ↑ “In Southern Rhodesia (subsequently Zimbabwe) and Northern Rhodesia (subsequently Zambia): an official document that the British colonial government required black Africans to carry, certifying the holder's personal details, tribal affiliation, and employment history. Now historical. Situpas were issued in the early to mid 20th cent., initially only to black African men, but later also to black African women. Black Africans protested against the situpa system, which severely restricted their movement, and enabled abusive labour practices and ethnic segregation.”

"situpa, n.". Oxford English Dictionary. Archived from the original on 2025-02-22. - ↑ “zvitupa

/zʋitupa/

noun, class(8) stem: chitupa dialects/origins: Karanga, Manyika, Zezuru

English translation

identity cards

Plural of chitupa.”

"zvitupa" (2019-01-16). VaShona Project. Archived from the original on 2025-02-22. - ↑ “The Carter Commission devised and recommended the concept of a conservative settlers’ ‘white only city’, which would in time, with sufficient immigration, be wholly white; otherwise it would compromise the white ideal. However, the economic inter-dependence of the two races (mainly by whites), and especially after the country experienced and accelerated industrialisation between the two major World Wars, made race segregation and separate development outright impossible and unrealistic; even before the Land Apportionment Act had been legislated. As the urban ‘white’ areas rapidly developed, the indigenous ‘blacks’, who provided cheap labour, could not be denied access to them. Thus, the careful, pernicious and exhaustive management and control of their movement into and within urban areas, and within the country as a whole, was deemed essential. Consequently, in 1936, the Natives Registration Act came into being, and has since morphed into the current national identification system, with similar subtle detrimental dictates for the majority of the people.”

Michelina Andreucci (2017-06-30). "The lingering legacy of colonialism: Part One…the situpa as an oppressive, racist instrument" The Patriot. Archived from the original on 2025-02-22. - ↑ “"Let me tell you, that time was very difficult. Each time you would move in the street, when you meet a policeman he would ask you for it [the pass]; 10 times a day. 10 policemen a day, you would have to produce it" [...] "Even when it was raining the policeman would stand where it's not raining while you were lining up, holding [the pass] in your hands. If you don't have it, you go and sleep in jail." [...] Harassment for passes was a common feature of life for African men living in Southern Rhodesian towns. As late as the end of the 1950s an African man in a large town might have been called on by roving police to produce as many as fourteen different documents.”

Teresa Barnes (1997). "Am I a Man?": Gender and the Pass Laws in Urban Colonial Zimbabwe, 1930-80, vol. Vol. 40, No. 1. African Studies Review. doi: 10.2307/525033 [HUB] - ↑ “Whites were exempt from this lingering, humiliating and time-consuming piece of colonial legislation.”

Michelina Andreucci (2017-06-30). "The lingering legacy of colonialism: Part One…the situpa as an oppressive, racist instrument" The Patriot. Archived from the original on 2025-02-22. - ↑ Gwisai, Munyaradzi. "Revolutionaries, resistance and crisis in Zimbabwe." Links International Journal of Socialist Renewal. Originally published in Leo Zeilig (ed.), Class Struggle and Resistance in Africa, New Clarion Press, Cheltenham, UK, 2002. Archived 2024-04-21.

- ↑ 23.00 23.01 23.02 23.03 23.04 23.05 23.06 23.07 23.08 23.09 23.10 23.11 23.12 23.13 David Martin and Phyllis Johnson (1981). The Struggle for Zimbabwe. London and Boston: Faber and Faber.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Alistair Boddy-Evans. (2019-08-13). "The Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland" ThoughtCo. Archived from the original on 2025-02-28.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Zimbabwe African Peoples Union (1972). Zimbabwe: History of a Struggle. [PDF] Cairo: The Afro-Asian Peoples' Solidarity Organization.

- ↑ “At one stage during the debate in Parliament, I asked for the insertion of a clause to the effect that if the Federation ever broke up, then Rhodesia would automatically be given its independence, in keeping with the current situation where we were being given a choice between independence or Federation. This certainly had the effect of putting the cat among the pigeons, and sent the government benches and their advisers running hither and thither. Eventually, however, they returned with the perfect reply: regrettably, my suggestion was impossible to execute, because one of the vital conditions of the Federation was that it was indissoluble, and any attempt to undermine this principle must be rejected.”

Ian Douglas Smith (2008). Bitter Harvest: Zimbabwe and the Aftermath of its Independence (p. 32). London: John Blake Publishing. - ↑ 27.0 27.1 Ian Douglas Smith (2008). Bitter Harvest: Zimbabwe and the Aftermath of its Independence (p. 38). London: John Blake Publishing.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 Ian Douglas Smith (2008). Bitter Harvest: Zimbabwe and the Aftermath of its Independence. London: John Blake Publishing.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 Felix Muchemwa (2017-03-23). "The Struggle For Land in Zimbabwe (1890 – 2010)……riots against Land Husbandry Act (1951)" The Patriot. Archived from the original on 2025-02-22.

- ↑ “Todd had acted positively in the territorial sphere in Southern Rhodesia, and had dealt surprisingly firmly with black agitation, which was beginning to rear its ugly head. He even went so far as to invoke a state of emergency in order to crush the trouble at Wankie, the big coal mine in north-west Matabeleland, in February 1954. But the other side of his character was ever present, and there was a constant feeling of unease among the members of his division of the United Federal Party over his tendency to give priority to black political advancement at the expense of economic and material advancement. The question came to a head when his cabinet colleagues discovered that behind their backs, he was involved in talks with Joshua Nkomo and the Reverend Ndabaningi Sithole, the leaders of the newly revived Southern Rhodesian African National Congress, which was engaged in massive intimidation campaigns in the battle for support among their own people. Clearly this placed them in the category of terrorist leaders.”

Ian Douglas Smith (2008). Bitter Harvest: Zimbabwe and the Aftermath of its Independence (p. 35). London: John Blake Publishing. - ↑ “ZANU was the fourth-born national party in the country. Born in August 1963 it had three elder brothers, two of whom had died as a result of the settler regime’s action in proscribing them. The African National Congress (ANC) formed in 1957 had been banned in 1959 when its leaders were detained. Comrade Joshua Nkomo was its leader. In January 1960, a new party, the National Democratic Party (NDP) was launched, and it was at that stage that I joined active nationalist politics, but the NDP was banned in December 1961. Again its leader had been Comrade Joshua Nkomo, although at the interim stage it had first been Michael Mawema and then the late Comrade Leopold Takawira.

In December 1961, ZAPU (Zimbabwe African People’s Union) was formed to replace the NDP, and it too was banned in September 1962. Its leader had also been Comrade Joshua Nkomo who continues to lead it after three successive bannings.”

Robert Gabriel Mugabe (1983). Our War of Liberation: 'The Role of ZANU in the Struggle: Address to the Guild of Mozambican Journalists in Maputo: October 28, 1978' (p. 64). Gweru: Mambo Press. - ↑ “In respect of the national front, the ANC in Zimbabwe had a strategy of non-collaboration with civil authority in rural areas and boycotts and strikes for urban centres. In rural areas, Africans refused to dip their cattle in conformity with the official destocking programme. The organisational effect of this strategy was good in some areas, but the areas affected were very few and the level of overall mass action was thus never achieved. In the urban areas, similarly, some boycott of buses and a few shops was organised for a limited period only, mainly in Salisbury. Again the action was not widespread nor was it lasting.

The African National Congress also lacked clarity in its ultimate objective. Although there was some talk of majority rule, the political struggle remained reformist in the sense of seeking remedial measures — more land, higher wages, better houses, more cattle, less taxes, no racial discrimination in public places. The principle of power totally transferring to the people had not emerged in any concrete form.

During the period of the NDP and ZAPU (ZAPU before it adopted the method of armed struggle) 1960 -— 1962, the political objectives became clearer and the principle of political power to the people expressed through the slogans ‘one-man-one-vote’ and ‘majority rule now’ took a solid concrete form. Equally, during this period the methods of struggle acquired both a quantitative and qualitative change.”

Robert Gabriel Mugabe (1983). Our War of Liberation: 'The Role of ZANU in the Struggle: Address to the Guild of Mozambican Journalists in Maputo: October 28, 1978' (pp. 64-5). Gweru: Mambo Press. - ↑ 33.0 33.1 Robert Gabriel Mugabe (1983). Our War of Liberation: 'The Role of ZANU in the Struggle: Address to the Guild of Mozambican Journalists in Maputo: October 28, 1978' (pp. 65-66). Gweru: Mambo Press.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 Masipula Sithole (2015). Zimbabwe: Struggles-within-the-Struggle. Harare: Rujeko Publishers. ISBN 0-7974-1935-7

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Robert Gabriel Mugabe (1983). Our War of Liberation: 'The Perspective of our Revolution: Article in The Zimbabwe News' (pp. 40-47). Gweru: Mambo Press.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Robert Gabriel Mugabe (1983). Our War of Liberation: 'The Role of ZANU in the Struggle: Address to the Guild of Mozambican Journalists in Maputo: October 28, 1978' (p. 66). Gweru: Mambo Press.

- ↑ Chirenje, J. Mutero. "A history of Zimbabwe for primary schools". 1982. pp. 72-4. (Image on p. 73).

- ↑ “chimurenga

/t͡ʃimuréŋa/

noun , class(7) synonyms: bongozozo dialects/origins: Zezuru

English translation

uprising

[...]

chimurenga

/t͡ʃimuréŋa/

noun , class(7) dialects/origins: Zezuru

English translation

revolution”

VaShona Project. Archived from the original on 2025-02-22. - ↑ “The word ‘Chimurenga’ has a number of meanings in current usage—revolution, war, struggle or resistance—and one of ZANU’s main slogans during the second Chimurenga war was ‘Pamberi ne Chimurenga’, meaning ‘forward with the struggle or the revolution’.”

David Martin and Phyllis Johnson (1981). Struggle for Zimbabwe. - ↑ “This book concentrates on the decisive phase of the struggle, from 21 December 1972, when a squad of nine ZANLA guerrillas attacked a settler farm in north-eastern Rhodesia. This attack marked the change from the sporadic, and militarily ineffectual, actions of the Sixties, to protracted armed struggle.”

David Martin and Phyllis Johnson (1981). Struggle for Zimbabwe (pp. xvi-xvii). - ↑ “The detente exercise of 1974—75 was clearly aimed at destroying our struggle with its emphasis as it was, on the ceasefire. We are glad that the Frontline Presidents now admit that they were wrong in insisting on a ceasefire as this gave an advantage to Smith. But ZANU suffered setbacks through the loss of its Chairman, Comrade Chitepo, and subsequent arrests which neutralised our fighters.”

Robert Gabriel Mugabe. Our War of Liberation: 'The Role of ZANU in the Struggle: Address to the Guild of Mozambican Journalists in Maputo: October 28, 1978'. - ↑ “It was a period between 1974-1975 when the liberation struggle had gone on abeyance. It was during this period when Kenneth Kaunda the then president of Zambia which was part of the Frontline States and John Voster the then president of South Africa were making efforts to bring the liberation struggle to a halt to pave way for independence through political negotiations.”

"Second Chimurenga". Pindula. Archived from the original on 2025-03-04. - ↑ “The first phase of the Bush war, which lasted from 1966 to 1970, was a turning point of the liberation struggle and focused on disrupting law and order ... The second phase of Chimurenga II (1971-1973) prioritized clandestine countryside infiltration; raising peasant awareness; self-reliance in recruitment, training, and logistics; establishing the process of seizing power; constitutional development; and preparing for a protracted hit-and-run war to exhaust and liquidate the Rhodesian regime ... The third phase of Chimurenga II (1974-1979) entailed a protracted intensification of military action, with Mozambique’s 1975 independence improving the ZANLA’s geopolitical situation and ability to expand the war, institutionalize ethos of purposeful transformation in its liberated zones, and access the midlands where the ZIPRA was already operating. An upsurge of peasants to front line states overwhelmed refugee camps, pressuring the ZANLA and the ZIPRA to shorten guerrilla-training periods.”

"The Second Chimurenga (ca. 1964)". Pamusoroi!. Archived from the original on 2025-03-04. - ↑ Tichaona Zindoga (2015-04-29). "Chinhoyi Battle: The last man standing" The Herald.

- ↑ "MK’s Luthuli Detachment and ZAPU in a joint operation" (2011-03-16). South African History Online. Archived from the original on 2025-03-04.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 Ireen Mahamba (2019-06-27). "Battle of the north-eastern frontier…when ZANLA came home" The Patriot.

- ↑ George T. Mudimu and Gregory Elich. "The Dynamics of Rural Capitalist Accumulation in Post-Land Reform Zimbabwe." MR Online, June 1, 2023. Archived 2023-04-13.

- ↑ "US plan to discredit Chinese investments unmasked" (2021-09-21). The Herald (Zimbabwe). Retrieved 24/06/2024.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 "Kuvimba Seeks $950 Million to Revive Zimbabwe’s Mining Sector" (2025-02). Battery Metals Africa. Archived from the original on 2025-02-28.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 Christopher Ojilere (2022-12-29). "Zimbabwe Bans All Lithium Exports" Voice of Nigeria. Archived from the original on 2022-12-30. Retrieved 2023-01-02.

- ↑ Dumisani Nyoni (2020-05-07). "Ten most mined minerals in Zimbabwe" Mining Zimbabwe.

- ↑ Rudairo Mapuranga (2024-09-26). "Kuvimba Partners with Chinese Firms for Sandawana, No Equity Stake for Chinese Firms" Mining Zimbabwe.

- ↑ Rudairo Mapuranga (2023-09-22). "Kuvimba plans to produce battery-grade lithium by 2030" Mining Zimbabwe.

- ↑ "Indigenisation 2.0: Zimbabwe plans new law giving it 26% of new mining projects. Here’s what it may look like" (2024-12-11). NewZWire. Archived from the original on 2024-12-11.

- ↑ Godfrey Marawanyika (2024-12-11). "Zimbabwe Wants 26% Free-Carry Stake in New Mining Projects" Bloomberg. Archived from the original.

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 Gregory Elich and Sam Moyo. "Reclaiming the Land: Land Reform and Agricultural Development in Zimbabwe: An Interview with Sam Moyo." MR Online, January 02, 2009. Archived 2023-04-13.

- ↑ "Our History." Commercial Farmers' Union of Zimbabwe, 2012-09-11. Archived 2025-02-28.

- ↑ "Who are we?" Commercial Farmers' Union of Zimbabwe, 2012-09-11. Archived 2025-02-28.

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 “Urban unemployment created a rush for the rural areas while the land redistribution had not yet been successfully addressed as it faced opposition from the historically-powerful white lobbying group, the Commercial Farmers Union (CFU), one of the strongest advocates for ESAP. [...] The CFU steadfastly opposed land reforms, believing changing from large-scale agribusiness to small-scale peasant agricultural farming with communal tenure would result in a devastated economy.”

Michelina Andreucci (2019-04-17). "ESAP and the West’s double standards." The Patriot. Archived from the original on 2025-02-28. - ↑ “In 1990, Zimbabwe launched a five-year Economic Structural Adjustment Policy (ESAP) substantially financed by the World Bank, International Monetary Fund and Western donor countries.”

Lloyd M. Sachikonye (1997). Social Movements in Development: 'Structural Adjustment and Democratization in Zimbabwe'. doi: 10.1007/978-1-349-25448-4_9 [HUB] - ↑ Chidiebere C Ogbonna "Targeted or Restrictive: Impact of U.S. and EU Sanctions on Education and Healthcare of Zimbabweans." September 2017, African Research Review 11(3):31 DOI:10.4314/afrrev.v11i3.4

- ↑ Tichaona Chifamba, Zhang Yuliang, Cao Kai. "Two-decade-old U.S. sanctions leave Zimbabweans suffering, triggering protests". Xinhua. 2022-07-11. Archived 2022-09-09.