More languages

More actions

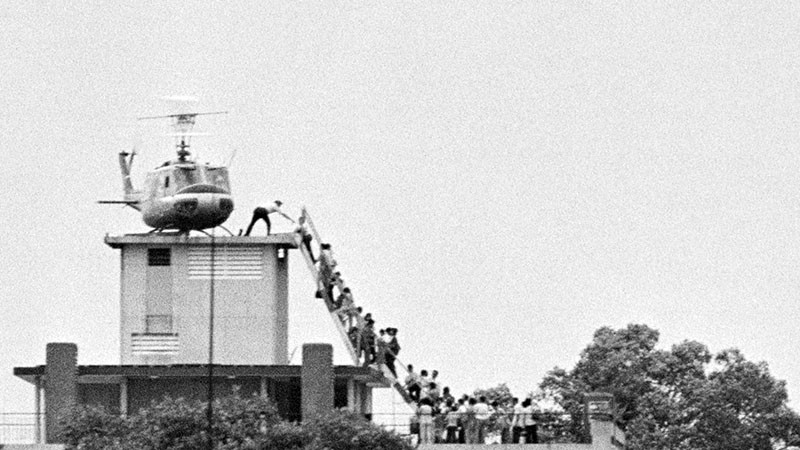

The Vietnam War (Chiến tranh Việt Nam), also known as the Second Indochina War or the Resistance War against the United States (Kháng chiến chống Mỹ), was a military conflict between the United States, South Vietnam, and their allies, and North Vietnam and its allies. The war began shortly after the division of Vietnam in 1954 as per the Geneva Conference and lasted until the Liberation of Saigon on 30 April 1975.[1] The United States entered the war directly in 1964 under false pretenses, namely the Gulf of Tonkin incident, a false-flag attack on American ships.[2] In total, the war killed three million Vietnamese soldiers and civilians.[3]

Background

During the Second World War, the Viet Minh led an anti-colonial guerrilla movement against the Japanese occupation of Vietnam.[4]

Japan was defeated in the fall of 1945 and left Indochina. Vietnamese revolutionaries led by Ho Chi Minh declared independence from France and briefly united their country for the first time in modern history.[5] The United States supported France against Vietnam and was providing 80% of its funding by 1953. Vietnamese forces led by Võ Nguyên Giáp defeated France at Điện Biên Phủ in 1954.

The 1954 Geneva Conference partitioned Vietnam into two states and planned to reunify them in 1956 following a national election. The United States created a corrupt, autocratic state in the south led by Ngô Đình Diệm and thwarted plans for reunification.[4]

U.S. invasion

The number of U.S. troops in Vietnam increased from 800 in early 1961 to 3,000 by the end of the year and 11,000 in 1962. They began as military advisers for the South Vietnamese army but later participated in combat operations against guerrillas in the south. After Kennedy's assassination in 1963, Lyndon Johnson escalated the war with bombing raids. He abandoned the guise of military advisers in 1965 and began openly fighting against communist forces.

By June 1967, U.S. troops were spending 86% of their time attempting to draw enemy troops out of hiding to fight them. The Vietnamese rarely fell for such traps and instead lured the U.S. into situations that would be advantageous for the revolutionaries.[6]

At the peak of the war in 1969, there were over 540,000 troops in Vietnam in addition to over 100,000 in nearby countries. Soldiers from U.S. satellite states such as Australia, New Zealand, the Philippines, Thailand, and south Korea also participated in the war. The south Vietnamese army also grew to a force of nearly a million by the end of the war. The United States retreated from Vietnam in early 1973 but continued to support the southern government until its defeat in 1975.[4]

U.S. war crimes

From 1967 to 1972, the CIA helped South Vietnam identify and kill suspected communist guerrillas as part of the Phoenix Program, causing at least 26,000 deaths.[citation needed]

Many commanders did not understand the Geneva Convention and believed they could legally kill or torture POWs. 60% of officers surveyed in 1969 said they would use or threaten torture, and 25% of lieutenants and warrant officers believed they could legally execute civilians for spying.[7]

U.S. officers rewarded soldiers for killing Vietnamese people, and soldiers with high kill counts received rest and recreation passes, extra food and beer, medals, badges, and light duty at base camp. In order to increase their kill count, soldiers often killed prisoners. However, in the event of large massacres, they often reported lower numbers or planted weapons on bodies to avoid suspicion.[6]

Massacres of civilians

On 21 October 1967, Lieutenant Robert Maynard ordered Marines to kill the entire population of Triệu Ái village in Quảng Trị Province following the death of a marine from a trap. Soldiers threw grenades into bomb shelters, burned houses, and killed a total of 12 civilians. Maynard was eventually court-martialed, but only for failing to properly report the incident.[7]

The U.S. Army killed almost 20 women and children in a village in Quảng Nam Province on 6 February 1968.[4]

In March 1968, US soldiers killed at least 347 unarmed civilians in Sơn Mỹ village.[8] The soldiers who tried to stop the massacre were considered traitors by the other soldiers and U.S. congressmen.[9]

In 1970, near the Minh Thanh rubber plantation in Bình Long Province, U.S. soldiers killed 10 civilians. They reported them as enemy soldiers, but investigators later discovered the victims' bodies with civilian identification cards and without military uniforms. Supposed weapons that they had been carrying ended up being bamboo shoots and agricultural tools. No soldiers were ever prosecuted for this massacre.[4]

U.S. soldiers killed 63 civilians at Truong Khanh. They reported 13 as enemy KIAs and claimed that 18 more died from airstrikes.[6]

Chemical weapons

The USA, as part of Operation Ranch Hand, used Agent Orange, a chemical weapon, over vast areas of jungle in Vietnam. The government of Vietnam states that 4 million people were exposed to the agent most of whom suffered life long illnesses and some of whom suffered birth defects.

Agent Orange was produced by the Dow Chemical Company and the Monsanto Company, as well as others.

South Korean war crimes

South Korean soldiers massacred civilians at An Truong near the city of Hội An on 9 January 1968.[4]

Casualties

Harvard Medical School and the University of Washington estimated a total of 3.8 million deaths including both civilians and soldiers.[4]

Imperialist forces

The USA lost 58,000 soldiers in Southeast Asia and 75,000 more became severely disabled. 254,000 south Vietnamese soldiers died and 783,000 were wounded.[4]

Revolutionary forces

Revolutionary forces lost 1.7 million troops, including one million in battle. 300,000 more went missing.[4]

Civilians

The USA killed at least 65,000 civilians in North Vietnam, mostly through air raids. In the south, 8,000 to 16,000 people were paralyzed, 30,000 to 60,000 became blind, and 83,000 to 166,000 became amputees. A quarter of wounded civilians were children under 13 years old.[4]

Legacy

In the USA, the Vietnam War was correctly considered a U.S. defeat until Ronald Reagan rebranded it as a "noble cause." Historians continue to deny or ignore U.S. war crimes.[4]

References

- ↑ Charles G. Boyd (1998). The Paris Agreement on Vietnam: Twenty-five Years Later. Washington, DC: The Nixon Center.

- ↑ Andrew Glass (2016-08-07). "Congress approves Gulf of Tonkin Resolution: Aug. 7, 1964" Politico. Retrieved 2022-01-05.

- ↑ Ziad Obermeyer, et al. (2008). Fifty years of violent war deaths from Vietnam to Bosnia: analysis of data from the world health survey programme. British Medical Journal. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a137 [HUB]

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 Nick Turse (2013). Kill Anything That Moves: 'Introduction' (pp. 11–22). [PDF] New York City: Metropolitan Books. ISBN 9780805086911 [LG]

- ↑ Howard Zinn (1980). A People's History of the United States: 'The Impossible Victory: Vietnam' (pp. 438–439). [PDF] HarperCollins. ISBN 0060194480

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Nick Turse (2013). Kill Anything That Moves: 'A System of Suffering' (pp. 40–46). [PDF] New York City: Metropolitan Books. ISBN 9780805086911 [LG]

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Nick Turse (2013). Kill Anything That Moves: 'The Massacre at Trieu Ai' (pp. 25–36). [PDF] New York City: Metropolitan Books. ISBN 9780805086911 [LG]

- ↑ Susan Brownmiller (1975). Against Our Will: Men, Women and Rape (pp. 103–05). Simon & Schuster. ISBN 9780671220624

- ↑ Hugh Thompson (2003). Moral Courage In Combat: The My Lai Story. [PDF] Center for the Study of Professional Military Ethics, United States Naval Academy.