More languages

More actions

| Hawaii Hawaiʻi | |

|---|---|

|

Ka Hae Hawaiʻi, Flag of the country of Hawaii as well as current state flag under U.S. occupation | |

| |

| Capital and largest city | Honolulu |

| Official languages | English, Hawaiian |

| History | |

• Unification of Hawaii | April 1810 |

• Monarchy overthrown | January 17, 1893 |

• U.S. annexation | July 4, 1898 |

• Statehood | August 21, 1959 |

| Area | |

• Total | 10,931 km² |

| Population | |

• 2020 census | 1,455,271 |

Hawaii (Hawaiʻi) is an US-occupied state in the Pacific Ocean. Although it is considered to be a state under U.S. law, this designation is challenged by the assertion that Hawaii is an illegally occupied nation whose people did not consent to its seizure and ongoing military occupation by the United States.[1]

Previously an internationally recognized sovereign indigenous monarchy, Hawaii was conquered by the US empire in 1893 in order to satisfy the economic and military interests of the US ruling class. The Hawaiian islands provide a strategic location for the U.S. military's presence in the Pacific, with 11 military bases on the island of Oʻahu alone, including Pearl Harbor, headquarters of the U.S. Pacific Command.[2] Hawaii was incorporated as a U.S. state in 1959, making it the most recent state to be incorporated into the U.S.

The scars of colonialism and anti-indigenous oppression remain to this day. In 2021, Empire Files reported that indigenous Hawaiians are fighting against the US Navy for polluting the island's water.[3]

The tourist economy of Hawaii leads to high real estate prices and a major housing crisis for working class Hawaiian families as available land is bought up and dominated by use for the tourist industry.[4] Hawaii has one of the highest rates of homelessness of the 50 U.S. states.[5] According to the 2020 Oʻahu Point-in-Time Count, over half of all homeless individuals in Oʻahu identified as Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander.[6] Partners in Care, an Oʻahu-based coalition dedicated to ending homelessness, estimates that Native Hawaiians and other Pacific Islanders are overrepresented by 210% in Oahu’s homeless population.[7]

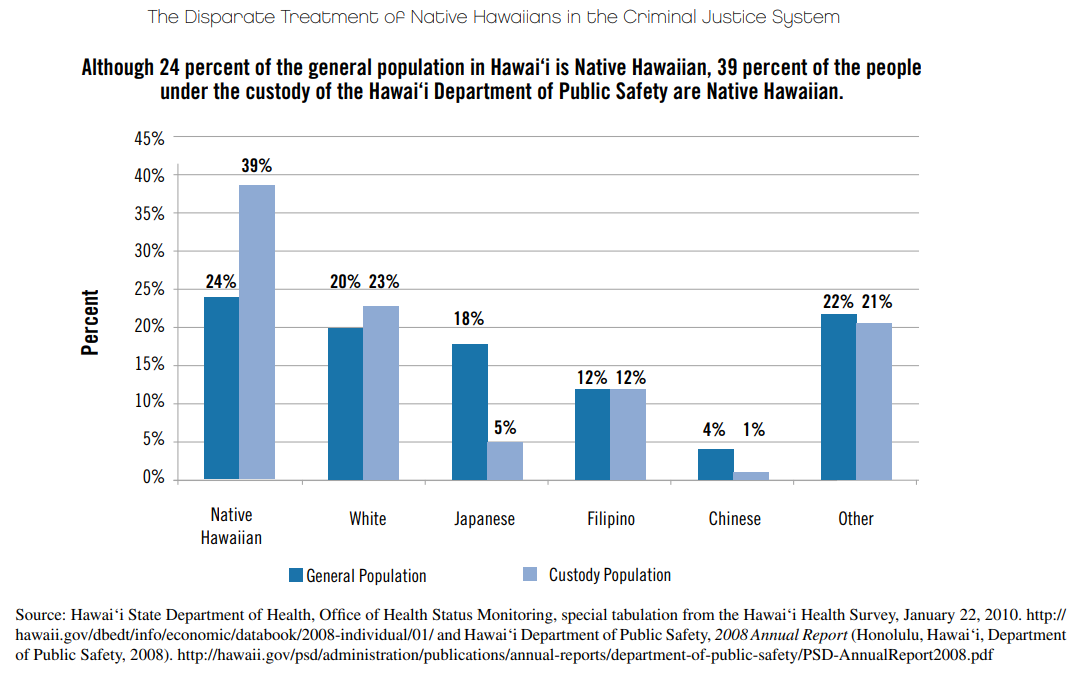

According to a 2010 report by the Office of Hawaiian Affairs, Native Hawaiians serve more time in prison and more time on probation than other racial or ethnic groups in the state. Native Hawaiians are also more likely to have their parole revoked and be returned to prison compared to other racial or ethnic groups. Additionally, Hawaii has the largest proportion of its population of women in prison compared to any other state, with Native Hawaiian women comprising a disproportionate number of women in the prison. Forty-four percent of the women incarcerated under the jurisdiction of the state of Hawaii are Native Hawaiian. Comparatively, 19.8 percent of the general population of women in Hawaii identify as Native Hawaiian or part Native Hawaiian. The report further states that incarcerated parents who lose their children may never get them back, and for many women in Hawaii prisons, this is a common occurrence. According to the report, Hawaii's prison institutions make the Hawaiian Native population "even more vulnerable than ever to the loss of land, culture, and community."[8]

The Hawaiian sovereignty movement is a grassroots political and cultural campaign to re-establish an autonomous or independent nation or kingdom of Hawaii due to desire for sovereignty, self-determination, and self-governance. Some groups also advocate for some form of redress from the United States for the 1893 overthrow of Queen Liliʻuokalani, and for the prolonged military occupation beginning with the 1898 annexation.

Geography[edit | edit source]

Hawaiʻi consists of eight main islands which are, from the northwest to southeast, Niʻihau, Kauaʻi, Oʻahu, Molokaʻi, Lānaʻi, Kahoʻolawe, Maui, and Hawaiʻi.

History[edit | edit source]

Early history[edit | edit source]

There is no definitive date for the Polynesian discovery of Hawaii, and the date of the first settlements of the Hawaiian Islands is a topic of continuing debate. Some estimates say that the Hawaiian people existed on the islands for over a millennium before Western contact.[9]

Early contact with colonizers[edit | edit source]

1778 marked the arrival of British captain James Cook, the first colonizer to try to explore and exploit Hawaiʻi. The Hawaiians defended the islands against Cook, ultimately killing him for his aggression against their nation. A 2017 Liberation School article notes that the British invasion "set in motion the arrival of an onslaught of missionaries and marauders who began to stake their claim to the Pacific island" and says that their aim was "to uproot the native economic and cultural system and replace it with a different social design based on a foreign religion and the supremacy of private property above all else" and well as "an interest in laying claim to Hawaiʻi’s vast wealth." The article goes on to point out that many of the chief capitalists who formed the initial colonial ruling class arrived as missionaries or were the sons of missionaries.[4]

Hawaiian Kingdom[edit | edit source]

King Kamehameha the First united the Hawaiian Islands in April 1810 and ruled until his death in 1819. In 1840, Kamehameha the Third voluntarily established a constitutional monarchy. The constitutional monarchy consisted of the king as head of state, two legislative houses, and a judiciary.

Hawaii's independence was recognized by the United States in 1842 and by Britain and France in 1843.

In 1874, King Lunalilo died without naming an heir, and the Hawaiian legislature elected Kalākaua as constitutional monarch.[10] The United States signed a treaty with the Hawaiian Kingdom in 1875, which gave them access to Pearl Harbor.[11]

In 1887, a pro-U.S. militia called the Honolulu Rifles threatened King Kalākaua and forced him to sign a new constitution without approval of the legislature. The Bayonet Constitution removed power from the king and made it so only the legislature could change or repeal laws.

King Kalākaua died in 1891 while visiting the United States and Queen Liliʻuokalani succeeded him.[10] Liluʻuokalani tried to pass a constitution preventing settlers from voting but was overthrown in 1893. The U.S. military surrounded the palace and forced her to give control of the islands to the Committee of Safety.[4]

Settler republic[edit | edit source]

In 1893, 160 troops from the USS Boston arrived in Hawaii and overthrew Queen Liliʻuokalani to establish the white-led Republic of Hawaii. President Grover Cleveland met with the coup leaders as well as indigenous Hawaiians and ended up condemning the coup.[1] The coup occurred with the foreknowledge of John L. Stevens, the U.S. minister to Hawaii, and 300 U.S. Marines from the Boston were called to Hawaii, allegedly to protect Statesian lives. On February 1, Minister John Stevens recognized Dole’s new government on his own authority and proclaimed Hawaii a U.S. protectorate. Dole submitted a treaty of annexation to the U.S. Senate, but most Democrats opposed it, especially after it was revealed that most Hawaiians did not want annexation.[12]

After declaring their republic in 1894, the settler rebels seized 1.8 million acres of Hawaiian land.[13] Sanford Dole, head of a committee acting on the behalf of the interests of the sugar industry, became the president of Hawaii.[14] His first cousin soon founded what is now the Dole Food Company.[13] In 1895, Robert Wilcox attempted a rebellion to restore the monarchy and Hawaiian sovereignty.[11]

In 1896, the Hawaiian language was banned. By 1897, 90 percent of Hawaiian nationals had signed what became known as the Kū’e Petitions opposing and effectively stopping legal annexation through a treaty between the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi and the United States. In 1898, the Spanish-Statesian War broke out, and the strategic use of the naval base at Pearl Harbor during the war convinced Congress to approve formal annexation. Despite mass opposition and local resistance, Hawaii was officially annexed by the United States in July 1898.[12][15]

Along with Hawaii, the USA also annexed Wake Island and eastern Samoa. President McKinley said that the annexation of Hawaii was even more important for the USA than the annexation of California.[13]

U.S. occupation[edit | edit source]

Hawaiʻi remained designated as a U.S. territory for another 60 years, and on August 21, 1959 Hawaiʻi was pronounced the 50th state of the United States of America.[15]

In 1993, President Bill Clinton issued an apology to the Native Hawaiian people in the form of a joint resolution passed in Congress called the Apology Resolution, and advocated for reconciliation efforts between Native Hawaiians and the U.S. government. He admitted to the fact that Hawaiians did not relinquish their inherent sovereignty or national lands, but stopped shy of admitting guilt in the violation of international law and circumvention of the rights of citizens of the Hawaiian Kingdom.[15]

According to an article from Intercontinental Cry, "Despite an abundance of prime agricultural land, Hawai’i has become almost exclusively reliant on the United States for its food."[15] Prior to occupation, Hawaii had an extensive and diversified agricultural system. That sustainable framework was supplanted by an agricultural system based around large scale production of sugar and pineapple for export. The last time Hawaii produced at least half of its own food was in the 1960s, just after its incorporation as a U.S. state.[16]

Foreign relations of independent Hawaiian government[edit | edit source]

U.S. Secretary of State John Calhoun recognized Hawaiian independence on July 6, 1846.[17] The Hawaiian government made treaties with and received recognition from the following countries before the U.S. invasion: Austro-Hungary, Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Great Britain, Italy, Japan, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Portugal, Russia, Samoa, Spain, Switzerland, Sweden, and Tahiti.[18]

Hawaiian genocide[edit | edit source]

From the beginning of European contact in 1778 to shortly after its annexation in 1898, the native Hawaiian population decreased by 90% due to colonization and disease.[19] After the USA-backed coup of Hawaii, the Hawaiian language was banned and children who spoke it were beaten.[20] Hawaiian is now considered a severely endangered language.[21]

Military[edit | edit source]

Pearl Harbor was handed over to the United States in 1887 and became a navy base. A quarter of Hawaiian land is now occupied by the U.S. military and there are 50,000 troops spread across the islands. 60 million rounds of ammunition are used on the islands every year by the U.S. military. Hawaiians protested against the military when they used Kahoʻolawe island for bombing runs.[4] The U.S. military has 19 bases in Hawaii and spends over $8 billion every year.[11]

[edit | edit source]

Since 1943, the U.S. Navy has stored upwards of 200 million gallons of fuel only about 100 feet above an underground aquifer on the island of Oahu, including at the Red Hill Bulk Fuel Storage Facility. In 2021, the Hawaii Department of Health announced that the Navy found gasoline and diesel-range hydrocarbons in the Red Hill shaft. The levels detected were up to 350 times what the State considers safe for drinking water, and that around 93,000 people had been affected. According to an article by Breakthrough News, the Navy claimed that the site of the polluting oil wells was critical for the "mission readiness" of the U.S. Indo-Pacific Command with what the US military has considered to be "increasing aggression" from Russia and China.[22] A 2022 article by the Honolulu Civil Beat states that the commander of the U.S. Pacific Fleet said Oahu residents had been right to believe Red Hill was unsafe, and that the results of two U.S. Pacific Fleet investigations into the disaster reveal that a leak on May 6 was much worse than initially reported – some 20,000 gallons escaped instead of the initially reported 1,000 – and that the failure to properly investigate that leak was a major factor in another one happening on Nov. 20. The second spill injected as many as 3,322 gallons of fuel into the drinking water, adding that the findings "back up community members’ longstanding concerns that Red Hill is fundamentally unsafe, a contention that the Navy denied for years – until now."[23] The US department of defense eventually announced plans for the permanent shut down the Red Hill fueling facility in 2022. Groups like Oʻahu Water Protectors, Sierra Club, Hawai’i Peace and Justice, Ka’ohewai and Ka Lāhui Hawaii Political Action Committee had been organizing for years against the hazardous tanks. The military has said that it is going to move to a fueling system in the Indo-Pacific, seeking contracts with other countries, while the defense department proposed a decentralized fueling arrangement for US military bases.[24]

Chemical and nuclear weapons[edit | edit source]

On the southern shores of Oʻahu, the military has dumped thousands of 55-gallon drums of radioactive waste into the ocean. In the 1960s, the military started using depleted uranium rounds for testing Davy Crockett nuclear systems. In 1967, as part of Red Oak Phase I, it fired rockets with sarin into the rainforest. In the 1970s, there were over 3,000 nuclear weapons on Oʻahu.[25]

Pohakuloa[edit | edit source]

The Pohakuloa Training Area in the center of Hawaii Island takes up 133,000 acres. The Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marines of the USA and other countries use this site for live-fire training and bombing.[25]

Incarceration[edit | edit source]

According to a 2010 report by the Office of Hawaiian Affairs, Hawaii's prison institutions make the Hawaiian Native population "even more vulnerable than ever to the loss of land, culture, and community" and that, in Hawaii, "Native Hawaiians are much more likely to get a prison sentence than almost all other groups, except for Native Americans" and notes that Native Hawaiians receive longer prison sentences than most other racial or ethnic groups, Native Hawaiians make up the highest percentage of people incarcerated in out-of-state facilities, and Native Hawaiian men and women are both disproportionately represented in Hawaii’s criminal justice system, but that the disparity is greater for women. In Hawaii, women make up a larger proportion (13 percent) of the prison system than any other state in the U.S. Incarcerated parents who lose their children may never get them back and for many women in Hawaii prisons, this is a common occurrence. Hawaii state law allows family courts to terminate parental rights when a child has been removed from a parent. In addition, persons with a criminal history are barred from becoming foster or adoptive parents, and simply living with, or being married to, a person convicted of a crime limits the individual family rights. Given that Native Hawaiians make up the largest percentage of the state prison population, the impact on families is widespread and affects many generations. Native Hawaiian youth were the most frequently arrested in all offense categories.[8]

The report states that "culturally inappropriate" or unavailable re-entry services are not as effective for helping Native Hawaiians achieve successful life outcomes and stay out of prison, citing research showing that "culturally relevant and appropriate" interventions and services are the most effective for helping Native Hawaiians participate fully in the community. The report contrasts "traditional social work modalities" practiced in U.S. institutions that stress "individualistic" Northern European and North American values of self-determination against Pacific cultures, including Native Hawaiians, which "tend to see themselves as part of a collective group or community", drawing the conclusion that the "application of Western values to a culture that does not share them makes it difficult to ensure successful implementation of initiatives or services." Such tendencies in the carceral system create a "particularly traumatic" situation for incarcerated Native Hawaiians, particularly when they are imprisoned out-of-state, due to the interruption of their connection to family, the land, and community.[8]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Jon Olsen (2022-11-15). "Hawai’i—The Very First U.S. Regime Change" CovertAction Magazine. Archived from the original on 2022-11-16. Retrieved 2022-11-18.

- ↑ Lowkey. “The Red Hill Disaster: Two Hawaiian Activists Discuss the Latest Episode in Two Centuries of Colonialism.” MintPress News. January 11, 2022. Archived 2022-08-23.

- ↑ Native Hawaiians Fight US Navy for Polluting Island’s Water (2021-12-30). Empire Files.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Danny Shaw (2017-07-17). "The struggle for self-determination in Hawaiʻi" Liberation School. Archived from the original on 2021-12-08. Retrieved 2022-06-20.

- ↑ "The 2020 Annual Homeless Assessment Report (AHAR) to Congress." The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. HUD Exchange. Archived 2022-08-23.

- ↑ "2020 O'ahu Point-In-Time Count: Comprehensive Report". Partners in Care. O'ahu's Continuum of Care. Archived 2022-08-23.

- ↑ Williamson Chang, Abbey Seitz. "It’s Time to Acknowledge Native Hawaiians' Special Right To Housing." January 8, 2021. Honolulu Civil Beat. Archived 2022-08-13.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 The Disparate Treatment of Native Hawaiians in the Criminal Justice System (2010). [PDF] Office of Hawaiian Affairs.

- ↑ “Aloha ‘Āina: Native Hawaiian Land Restitution.” 2020. Harvardlawreview.org. April 3, 2020.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 "Political History". The Hawaiian Kingdom. Archived from the original on 2021-10-29.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 "RIMPAC and the Military Occupation of Hawai‘i" (2016-08-16). The Red Nation. Archived from the original on 2022-06-29. Retrieved 2022-08-30.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 “Americans Overthrow Hawaiian Monarchy.” History.com. February 9, 2010.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 David Vine (2020). The United States of War: 'Going Global' (p. 189). Oakland: University of California Press. ISBN 9780520972070 [LG]

- ↑ “Sanford Ballard Dole | President of the Republic of Hawaii | Britannica.” Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 Imani Altemus-Williams. 2015. “Towards Hawaiian Independence | Intercontinental Cry.” Intercontinentalcry.org. December 7, 2015. Archived 2022-08-24.

- ↑ Terrell, Jessica. “Hawaii’s Food System Is Broken. Now Is the Time to Fix It.” Honolulu Civil Beat. January 27, 2021.

- ↑ John Calhoun (1846). Recognition of Hawaiian Independence. [PDF] Archives of Hawaii.

- ↑ "Recognition of Hawaiian Independence". Hawaiian Kingdom. Archived from the original on 2022-11-02. Retrieved 2022-11-18.

- ↑ Stephanie Launiu (2021-09-07). "11 Things You May Not Know About Hawai'i and Native Hawaiians" Wander Wisdom. Archived from the original on 2021-10-13. Retrieved 2022-01-16.

- ↑ United States Native Hawaiians Study Commission (1983). Native Hawaiians Study Commission : report on the culture, needs, and concerns of native Hawaiians.. Washington, D.C.: United States Department of the Interior.

- ↑ "Hawaiian". Endangered Languages Project. Archived from the original on 2021-12-28. Retrieved 2022-01-16.

- ↑ "Hawaiians Demand Justice after Pollution of Water Source from Navy Facility." Breakthrough News. 2021. Breakthroughnews.org. 2021. Archived 2022-08-23.

- ↑ Jedra, Christina. 2022. “Red Hill Investigations: The Navy Failed to Prevent and Respond to Fuel Contamination.” Honolulu Civil Beat. Honolulu Civil Beat. July 2022. Archived 2022-08-23.

- ↑ Peoples Dispatch. 2022. “Hawaiian Activists Celebrate Closure Announcement of Navy’s Fuel Facility : Peoples Dispatch.” Peoples Dispatch. March 9, 2022. Archived 2022-08-23.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Jim Albertini (2023-06-02). "The U.S. Military in Hawaii: The Dark Side of Paradise!" CovertAction Magazine. Archived from the original on 2023-06-09.