More languages

More actions

| Some parts of this article were copied from external sources and may contain errors or lack of appropriate formatting. You can help improve this article by editing it and cleaning it up. |

Alberto Kenya Fujimori Inomoto 藤森 謙也 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | July 28, 1938 Miraflores, Lima, Peru |

| Died | 11 September 2024 (age 86) Lima, Peru |

| Nationality | Peruvian |

| Political orientation | Anti-communism Fascism (Fujimorism) Neoliberalism Social conservativism |

| Political party | Change 90 (1990–1998) Sí Cumple (1988–2010) People's New Party (2007–2013) Popular Force (2024) |

Alberto Kenya Fujimori Inomoto[1] (28 July 1938 – 11 September 2024)[2][3] was a Peruvian former politician, professor and engineer who was President of Peru from 28 July 1990 until 22 November 2000, though de facto leadership was reportedly held by head of the National Intelligence Service (Peru), Vladimiro Montesinos.[4] He was frequently described as a dictator.[5][6] His government was permeated by a network of corruption organized by his associate Montesinos.[7][8][9][5] He was sentenced to 25 years in prison for human rights abuses in 2009, but was released early in 2023.

A Peruvian of Japanese descent,[10] Fujimori studied to be an agricultural engineer and later obtain a master's degree in mathematics. From 1984 to 1989 he served as rector of the National Agrarian University before winning the presidency in the 1990 Peruvian general election.

1992 Peruvian CIA-backed coup[edit | edit source]

Sometimes known as the Fujimorazo,[11][12], a 'self-coup' (autogolpe) was performed in Peru in 1992 after Alberto Fujimori dissolved the Congress as well as the judiciary and assumed full legislative and judicial powers. With the collaboration of the military, the Fujimori government subsequently began to implement objectives of the Green Plan (Plan Verde) following the coup.

Background[edit | edit source]

Under the military government of Juan Velasco Alvarado, Peru's debt increased greatly due to excessive borrowing and the 1970s energy crisis.[13] The economic policy of President Alan García distanced Peru from international markets further, resulting in lower foreign investment in the country.[14] Under García, Peru experienced extreme inflation and increased confrontations with the guerrilla group Shining Path, leading the country towards high levels of instability.[15]

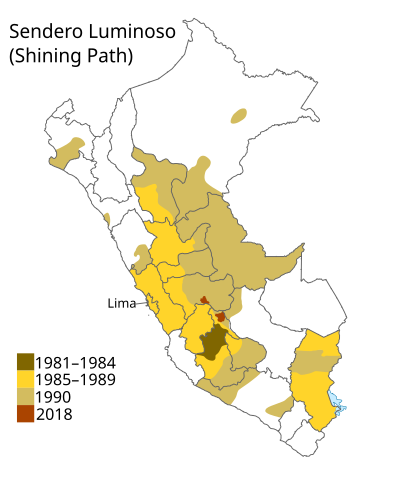

Much of Peru was controlled by the Maoist insurgent group Sendero Luminoso ("Shining Path"), who was engaged in a struggle that had devolved into terrorism due to the Abimael Guzmán-led gross misreading of Mao, and to a lesser extent the competing Túpac Amaru Revolutionary Movement (MRTA) also had political sway. (This article will focus on the Shining Path.) In 1989, 25% of Peru's district and provincial councils opted not to hold elections, owing to a persistent campaign of assassination, over the course of which over 100 officials had been killed by the Shining Path in that year alone. That same year, more than one-third of Peru's courts lacked a justice of the peace due to Shining Path intimidation. Labor union leaders and military officials were also assassinated throughout the 1980s.[16]

By the early 1990s, some parts of the country were under the control of the Maoists, in territories known as "zonas liberadas" ("liberated zones"), where inhabitants lived under the rule of these groups and paid them taxes.[17] When the Shining Path arrived in Lima, it organized "paros armados" ("armed strikes"), which were enforced by killings and other forms of violence. The leadership of the Shining Path largely consisted of university students and teachers.[18] Two previous governments, those of Fernando Belaúnde Terry and Alan García, at first neglected the threat posed by the Shining Path, then launched an unsuccessful military campaign to eradicate it, undermining public faith in the state and precipitating an exodus of elites.[19]

In October 1989, Plan Verde, a clandestine military operation, was developed by the armed forces of Peru during the internal conflict in Peru; it involved the genocide of impoverished and indigenous Peruvians, the control or censorship of media in the nation and the establishment of a neoliberal economy in Peru.[20][15][21] Initially a coup d'état was included in the plan, though this was opposed by Anthony C. E. Quainton, the United States Ambassador to Peru.[22] Military planners also decided against the coup as they expected a neoliberal candidate to be elected in the 1990 Peruvian general election.[22] Rendón writes that the United States supported Fujimori because of his relationship with Vladimiro Montesinos, a former Peruvian intelligence officer who was charged with spying on the Peruvian military for the Central Intelligence Agency.[23][24] Summarizing alleged support for Fujimori's candidacy from the United States, Rendón writes, "If Vargas Llosa with liberal democracy was very polarizing and a danger to American interests in the region, Fujimori with authoritarianism was very consensual and more in line with American interests in Peru and the region".[24]

The Plan Verde called for the "total extermination" of "culturally backward and economically impoverished groups" determined by the Peruvian military in Plan Verde,[25][21][26][27] from 1996 to 2000, the Fujimori government oversaw a massive forced sterilization campaign known as the National Program for Reproductive Health and Family Planning (PNSRPF). According to Back and Zavala, the plan was an example of ethnocide as it targeted indigenous and rural women.[27] The United Nations and other international aid agencies supported this campaign. USAID provided funding and training until it was exposed by objections by churches and human rights groups.[28] The Nippon Foundation, headed by Ayako Sono, a Japanese novelist and personal friend of Fujimori, supported it as well.[29][30] In the four-year Plan Verde period, over 215,000 people, mostly women, entirely indigenous, were forced or threatened into sterilization and 16,547 men were forced to undergo vasectomies during these years, most of them without a proper anesthetist, in contrast to 80,385 sterilizations and 2,795 vasectomies over the previous three years.[31]

Upon winning election, and before inauguration, Fujimori was shown the Plan Verde. With the compliance of Fujimori, plans for a coup as designed in Plan Verde were prepared over a two-year period prior to April 1992.[23][32][21] Fujimori and his military handlers had planned for a coup during his preceding two years in office.[32][23][33] The armed forces finalized plans on 18 June 1990 involving multiple scenarios for a coup to be executed on 27 July 1990, the day prior to Fujimori's inauguration.[33] The magazine noted that in one of the scenarios, titled "Negotiation and agreement with Fujimori. Bases of negotiation: concept of directed Democracy and Market Economy", Fujimori was to be directed on accepting the military's plan at least twenty-four hours before his inauguration.[33] Rospigliosi states "an understanding was established between Fujimori, Montesinos and some of the military officers" involved in Plan Verde prior to Fujimori's inauguration.[22]

Fujimori abandoned the economic platform he promoted during his campaign, adopting more aggressive neoliberal policies than those espoused by his competitor in the election.[34] During his first term in office, Fujimori enacted wide-ranging neoliberal reforms, known as "Fujishock". This program bore little resemblance to his campaign platform and was in fact more drastic than anything Vargas Llosa had proposed.[35] Hernando de Soto, the founder of one of the first neoliberal organizations in Latin America, Institute for Liberty and Democracy (ILD), began to receive assistance from Ronald Reagan's administration, with the National Endowment for Democracy's Center for International Private Enterprise (CIPE) providing his ILD with funding and education for advertising campaigns.[36][37][38] Between 1988 and 1995, de Soto and the ILD were mainly responsible for some four hundred initiatives, laws, and regulations that led to significant changes in Peru's economic system.[39][40] Under Fujimori, de Soto served as "the President's personal representative", with The New York Times describing de Soto as an "overseas salesman" for Fujimori in 1990, writing that he had represented the government when meeting with creditors and United States representatives.[39] Others dubbed de Soto as the "informal president" for Fujimori.[36]The IMF was content with Peru's measures, and guaranteed loan funding for Peru.[41] Inflation rapidly began to fall and foreign investment capital flooded in.[41]

In Fujimori's first term of office, over 3,000 Peruvians were killed in political murders.[42] American Popular Revolutionary Alliance (APRA) and Vargas Llosa's party, the Democratic Front (FREDEMO), remained in control of both chambers of Congress of the Republic of Peru, the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate, hampering the enactment of economic reform. The Congress – which consisted mainly of opposition parties – granted Fujimori legislative power on fifteen separate occasions, which allowed him to enact 158 laws.[43] However, the Congress resisted Fujimori's efforts to adopt policies advocated by the International Monetary Fund and World Bank, especially austerity measures. Fujimori also had difficulty combatting the Maoist Shining Path (Template:Lang-es) guerrilla organization due largely to what he perceived as intransigence and obstructionism in Congress.

In response to the political deadlock, Fujimori, with the support of the military, on 5 April 1992, carried out a self-coup,[44] also known as the autogolpe (auto-coup) or Fujigolpe (Fuji-coup) in Peru. Congress was shut down by the military, the constitution was suspended and the judiciary was.[45] Without political obstacles, the military was able to implement the objectives outlined in Plan Verde[23][32][33] while Fujimori served as a figurehead leader to project an image that Peru was supporting a liberal democracy.[4][46] Montesinos would go on to adopt the actual function of Peru's government.[46]

On the night of Sunday April, 5, 1992, Fujimori appeared on television and announced that he was "temporarily dissolving" the Congress of the Republic and "reorganizing" the Judicial Branch of the government. He then ordered the Peruvian Army to drive a tank to the steps of Congress to shut it down. When a group of senators attempted to hold session, tear gas was deployed against them. Fujimori issued Decree Law 25418, which dissolved the Congress, gave the Executive Branch all legislative powers, suspended much of the Constitution of Peru, and gave the president the power to enact full legislative and judicial powers, such as the "application of drastic punishments" towards "terrorists". He served as a figurehead president under Montesinos and the Peruvian Armed Forces. Fujimori called for elections of a new congress that was later named the Democratic Constitutional Congress (Congreso Constituyente Democrático); Fujimori later received a majority in this new congress, which later drafted the 1993 Constitution. Fujimori also set about curtailing the independence of the judiciary and constitutional rights with a declaration of a state of emergency and curfews, as well as enacting controversial "severe emergency laws" to deal with terrorism.[4][46] and would reportedly adopt Plan Verde – a plan that involved the genocide of impoverished and indigenous Peruvians, the control or censorship of media in the nation and the establishment of a neoliberal economy controlled by a military junta.[47][20][48][23][22][49]

Following the coup, Peruvian newspapers, radio and television stations were occupied by the military beginning at 10:30 pm on 5 April and remained for forty hours until 7 April, limiting initial response from domestic media.[50] During the period, only the Fujimori government was granted to communicate with the public and all newspapers were printed under military observation and contained similar content; every publication was ordered to not include the word "coup".[50]

Insurgent activity was in decline by the end of 1992,[51] but Fujimori would take credit for this abatement, claiming that his campaign had largely eliminated the insurgent threat. After the 1992 auto-coup, the intelligence work of the DIRCOTE (National Counter-Terrorism Directorate) led to the capture of the leaders from MRTA and the Shining Path, including notorious Shining Path leader Abimael Guzmán. Guzmán's capture was a political coup for Fujimori, who used it to great effect in the press; in an interview with documentarian Ellen Perry, Fujimori even notes that he specially ordered Guzmán's prison jumpsuit to be white with black stripes, to enhance the image of his capture in the media.[52]

International business colluded with the government in "privatization".[53][54] The privatization campaign involved selling off of hundreds of state-owned enterprises, and replacing the country's troubled currency, the Peruvian inti, with the Peruvian nuevo sol.[55] Fujimori eliminated price controls, drastically reduced government subsidies and government employment, eliminated all exchange controls, and also reduced restrictions on investment, imports, and capital.[53] Tariffs were simplified, the minimum wage was quadrupled, and the government established a $400 million poverty relief fund.[53] The latter seemed to anticipate the economic agony to come: the price of electricity quintupled, water prices rose eightfold, and gasoline prices 3,000%.[35][53] Subsequent analysis has said that the description of Fujimori's economic achievements as a "Peruvian miracle" was exaggerated and that inequality in Peru persisted following his tenure.[56] According to Peruvian sociologist and political analyst Fernando Rospigliosi, Peru's business elites held relationships with the military planners, with Rospigliosi writing that businesses "probably provided the economic ideas which [the military] agreed with, the necessity of a liberal economic program as well as the installment of an authoritarian government which would impose order".[22] Rospigliosi also states that "an understanding was established between Fujimori, Montesinos and some of the military officers" involved in Plan Verde prior to Fujimori's inauguration.[22]

The economist Hernando de Soto, with the assistance and funding of the Atlas Network, created the Institute for Liberty and Democracy (ILD), one of the first neoliberal organizations in Latin America[37] – served informally as Fujimori's "personal representative" for the first three years of his government and recommended a "shock" to Peru's economy, stating "This society is collapsing, without a doubt, ... But the problems here are so entrenched that you have to have a collapse before you can implement fundamental changes in the political system".[57][58] De Soto convinced Fujimori to travel to New York City in a meeting organized by the Peruvian Javier Pérez de Cuéllar, secretary general of the United Nations, where they met with the heads of the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, and the Inter-American Development Bank, who convinced Fujimori to follow the guidelines for economic policy set by the international financial institutions.[57][59] The policies included a 300 percent tax increase, unregulated prices and privatizing two-hundred and fifty state-owned entities.[57]

One of those responsible for maintaining an image of apparent honesty and government approval was Vladimiro Montesinos, head of the National Intelligence Service (SIN), who systematically bribed politicians, judges and the media. That criminal network also involved authorities of his government; furthermore, due to privatisation and the arrival of foreign capital, companies close to the Ministry of Economy were allowed to use state money for public works tenders, as in the cases of AeroPerú, JJC Contratistas Generales (of the Camet Dickmann family) and the Banco de Crédito del Perú. Although in 1999 the opposition made a public denunciation that ended in the resignation of five ministers, this network was later revealed in 2000, just before the president resigned, when the Swiss embassy in Peru informed the then Minister of Justice Alberto Bustamante and the attorney general José Ugaz of more than 40 million dollars coming from Montesinos, in which he was denounced for "illicit enrichment to the detriment of the Peruvian state".[60]

With FREDEMO dissolved and APRA leader Alan García exiled to Colombia, Fujimori sought to legitimize his position. He called elections for a Democratic Constitutional Congress, to serve as a legislature and as a constituent assembly. The American Popular Revolutionary Alliance (APRA) and Popular Action of Peru attempted a boycott of this election, but the Christian People's Party of Peru (PPC, not to be confused with PCP, Partido Comunista del Peru, or "Peruvian Communist Party") and many left-leaning parties participated in this election. Fujimori supporters won a majority of the seats in this body and drafted a new Constitution of Peru in 1993. In a 1993 constitutional referendum, the coup and the Constitution of 1993 were approved by a margin of less than five percent.[61]

The 1993 Constitution allowed Fujimori to run for a second term, and in April 1995, at the height of his popularity, Fujimori easily won reelection with almost two-thirds of the vote. His major opponent, former Secretary-General of the United Nations Javier Pérez de Cuéllar, won only 21 percent of the vote. Fujimori's supporters won comfortable majority in the newly unicameral Congress of the Republic of Peru. One of the first acts of the new congress was to declare an amnesty for all members of the Peruvian Armed Forces or police accused or convicted of human rights abuses between 1980 and 1995.[62]

The 1995 election was the turning point in Fujimori's career. Peruvians began to be more concerned about freedom of speech and the press. However, before he was sworn in for a second term, Fujimori stripped two universities of their autonomy and reshuffled the national electoral board. This led his opponents to call him "Chinochet," a reference to his previous nickname and to Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet.[63] Modeling his rule after Pinochet, Fujimori reportedly enjoyed this nickname.[64]

The 1993 constitution limited a presidency to two terms. Shortly after Fujimori began his second term, his supporters in Congress passed a law of "authentic interpretation" which effectively allowed him to run for another term in 2000. A 1998 effort to repeal this law by referendum failed.[65] In late 1999, Fujimori announced that he would run for a third term. Peruvian electoral bodies, which were politically sympathetic to Fujimori, accepted his argument that the two-term restriction did not apply to him, as it was enacted while he was already in office.[66]

Exit polls showed Fujimori fell short of the 50% required to avoid an electoral runoff, but the first official results showed him with 49.6% of the vote, just short of outright victory. Eventually, Fujimori was credited with 49.89%—20,000 votes short of avoiding a runoff. Despite reports of numerous irregularities, the international observers recognized an adjusted victory of Fujimori. His primary opponent, Alejandro Toledo, called for his supporters to spoil their ballots in the runoff by writing "No to fraud!" on them (voting is mandatory in Peru). International observers pulled out of the country after Fujimori refused to delay the runoff.

In the runoff, Fujimori won with 51.1% of the total votes. While votes for Toledo declined from 37.0% of the total votes cast in the first round to 17.7% of the votes in the second round, invalid votes jumped from 8.1% of the total votes cast in the first round to 31.1% of total votes in the second round.[67] The large percentage of invalid votes in this election suggests that many Peruvians took Toledo's advice and spoiled their ballots.

Although Fujimori won the runoff with only a bare majority (but 3/4 valid votes), rumors of irregularities led most of the international community to shun his third swearing-in on 28 July. For the next seven weeks, there were daily demonstrations in front of the presidential palace. As a conciliatory gesture, Fujimori appointed former opposition candidate Federico Salas as prime minister. However, opposition parties in Congress refused to support this move, and Toledo campaigned vigorously to have the election annulled. At this point, a corruption scandal involving Vladimiro Montesinos broke out, and exploded into full force on the evening of 14 September 2000, when the cable television station Canal N broadcast footage of Montesinos apparently bribing opposition congressman Alberto Kouri for defecting to Fujimori's Peru 2000 party. The video was presented by Fernando Olivera, leader of the Independent Moralizing Front (FIM), who purchased it from one of Montesinos's closest alliesTemplate:Who (nicknamed by the Peruvian press El Patriota).

With multimillion-dollar annual expenditures in 1992 (five billion dollars in public spending plus another five billion in state enterprises), part of the funds were diverted to political and military institutions. According to the National Anti-Corruption Initiative (INA) in 2001, they corresponded to 30–35% of the average budget expenditure in each year, and 4% of the average annual GDP during the same period.[68]

=Reactions to the Coup[edit | edit source]

On 13 November 1992, General Jaime Salinas led a failed military coup. Salinas asserted that his intentions were to turn Fujimori over to be tried for violating the Peruvian constitution.[69] Another group of military officers led by General Jaime Salinas Sedó attempted to overthrow Fujimori on 13 November, but failed.

In response to the Fujimori regime, Various states individually condemned the coup, international financial organizations delayed planned or projected loans, and the United States government suspended all aid to Peru other than humanitarian assistance, as did Germany and Spain. Venezuela broke off diplomatic relations, and Argentina withdrew its ambassador. Chile joined Argentina in requesting Peru's suspension from the Organization of American States. The coup appeared to threaten the reinsertion strategy for economic recovery, and complicated the process of clearing Peru's arrears with the International Monetary Fund.

Two weeks after the coup, the Bush administration changed their position and officially recognized Fujimori as the legitimate leader of Peru. The Organization of American States and the U.S. agreed that Fujimori's coup may have been extreme, ultimately was allegedly good for Peru. In fact, the coup came not long after the U.S. government and media had launched a media offensive against the Shining Path rural guerrilla movement. On March 12, 1992, Undersecretary of State for Latin American Affairs Bernard Aronson told the Congress of the United States: "The international community and respected human rights organizations must focus the spotlight of world attention on the threat which Sendero poses... Latin America has seen violence and terror, but none like Sendero's... and make no mistake, if Sendero were to take power, we would see... genocide."

Fujimori, in turn, would later receive most of the participants of the November 1992 Venezuelan coup attempt as political asylees, who had fled to Peru after its failure.[70]

Peruvian–U.S. relations earlier in Fujimori's presidency had been dominated by questions of coca eradication and Fujimori's initial reluctance to sign an accord to increase his military's eradication efforts in the lowlands. Fujimori's autogolpe became a major obstacle to relations, as the United States immediately suspended all military and economic aid, with exceptions for counter-narcotic and humanitarian funds.[71] Two weeks after the self-coup, however, the George H.W. Bush administration changed its position and officially recognized Fujimori as the legitimate leader of Peru, partly because he was willing to implement economic austerity measures, but also because of his adamant opposition to the Shining Path.[72]

During his tenure, his policies primarily received support from the military, Peru's upper class and international financial institutions, helping him maintain control of Peru.[73] His supporters credit his government with the creation of Fujimorism, defeating the Shining Path insurgency and neoliberal economic policies.[74][75] Neoliberal policies and his political ideology of Fujimorism have influenced the governance of Peru into the present day through a cult of personality.[76]

Some analysts state that some of the GDP growth during the Fujimori years actually reflects a greater rate of extraction of nonrenewable resources by transnational companies; these companies were attracted by Fujimori by means of near-zero royalties, and, by the same fact, little of the extracted wealth has stayed in the country.[77][78][79][80] Peru's mining legislation, they claim, has served as a role model for other countries that wish to become more mining-friendly.[81]

A congressional investigation in 2002, led by socialist opposition congressman Javier Díez Canseco, stated that of the US$9 billion raised through the privatizations of hundreds of state-owned enterprises, only a small fraction of this income ever benefited the Peruvian people.[citation needed] The sole instance of organized labor's success in impeding reforms, namely the teacher's union resistance to education reform, was based on traditional methods of organization and resistance: strikes and street demonstrations.[82]

Retreat to Japan[edit | edit source]

In November 13, 2000, Fujimori escaped to Japan, for political refuge, to bypass conviction by the government of Peru.[83]

After Fujimori fled to Japan, the government of Peru requested his extradition, but Japan did not extradite Fujimori; because Japan recognizes Fujimori as a Japanese citizen rather than a Peruvian citizen due to the Master Nationality Rule, and Japan refuses to extradite its citizens to other countries.[84]

Arrest[edit | edit source]

On 6 November 2005, Alberto Fujimori unexpectedly arrived in Santiago, Chile. He was asserted and extradited to Peru on 22 September 2007, where he would be imprisoned for 25 years.

The Barrios Altos massacre was one of the crimes cited in the request for Fujimori's extradition from Japan to Peru in 2003. The La Cantuta massacre, and The 1991 Barrios Altos massacre by members of the death squad Grupo Colina, made up solely of members of the military of Peru, was one of the crimes that Peru cited in its request to Japan for his extradition in 2003. In October 2007, pursuant to a 2006 ruling from the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, the government extended a formal apology for the massacre and undertook to make amends to the victims' next-of-kin, including compensation in the amount of US$1.8 million.[85]

On 8 April 2008, a court found a number of people, including Julio Salazar, guilty of kidnapping, homicide, and forced disappearance.[86]

In 2009 it was determined by a judicial ruling that not a single one of the victims in La Cantuta massacre was linked to any terrorist organization,[87] it was in the same ruling that condemned Fujimori to a 25 years imprisonment for crimes against humanity.[88]

On November 26, 2007, ten former government officials were sentenced by the Supreme Court of Peru for their role in the coup. Fujimori's Minister of the Interior, Juan Briones Dávila, was sentenced to ten years imprisonment. Former Fujimorist congressmen Jaime Yoshiyama, Carlos Boloña, Absalón Vásquez, Víctor Joy Way, Óscar de la Puente Raygada, Jaime Sobero, Alfredo Ross Antezana, Víctor Paredes Guerra, and Augusto Antoniolli Vásquez were all also sentenced for various crimes such as rebellion and kidnapping.

Fujimori was convicted in 2009 for the kidnapping of journalist Gustavo Gorriti and businessman Samuel Dyer, both of whom were detained by the military on the night of the self coup.

In May 2023, the Supreme Court of Chile ordered Fujimori to testify regarding forced sterilizations that occurred between 1996 and 2000 during his government, with Chile attempting to decide if they would expand extradition charges against Fujimori to include the sterilizations, which would allow him to be prosecuted in Peru.[89] On 19 May 2023, Fujimori participated in a video call from Barbadillo Prison with justice officials in Chile defending his actions regarding sterilizations.[90]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ "General Data". Infogob. Archived from the original on 25 April 2012.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 11 April 2019.

- ↑ "Fujimori sacó DNI con fecha falsa sobre su nacimiento" (22 May 2019). larepublica.pe.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2

“In the 1990s, Peru was run ... by its secret-police chief, Vladimiro Montesinos Torres.”

How to Subvert Democracy: Montesinos in Peru (Autumn 2004). The Journal of Economic Perspectives, vol.18 (p. 69). doi: 10.1257/0895330042632690 [HUB]- “The coup of April 5, 1992, carried out by high-ranking military felons who used the President of the Republic himself as their figurehead, had as one of its stated objectives a guaranteed free hand for the armed forces in the anti-subversion campaign, the same armed forces for whom the democratic system – a critical Congress, an independent judiciary, a free press – constituted an intolerable obstacle.”

"Ideas & Trends: In His Words; Unmasking the Killers in Peru Won't Bring Democracy Back to Life" (1994-03-27). - “Lester: Though few questioned it , Montesinos was a novel choice. Peru's army had banished him for selling secrets to America's CIA, but he'd prospered as a defence lawyer – for accused drug traffickers. ... Lester: Did Fujmori control Montesinos or did Montesinos control Fujimori? ... [Michael] Shifter: As information comes out, it seems increasingly clear that Montesinos was the power in Peru.”

"Spymaster" (August 2002). - “Mr Montesinos ... and his military faction, ... for the moment, has chosen to keep Mr Fujimori as its civilian figurehead”

Fujimori in OAS talks PERU CRISIS UNCERTAINTY DEEPENS AFTER RETURN OF EX-SPY CHIEF (26 October 2000). - “Alberto Fujimori,... as later events would seem to confirm—merely the figurehead of a regime governed for all practical purposes by the Intelligence Service and the leadership of the armed forces”

"THE CRISIS OF DEMOCRATIC GOVERNANCE IN THE ANDES" (2001). Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. - “Fujimori became a kind of, well, a figurehead”

"Questions And Answers: Mario Vargas Llosa" (9 January 2001).

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 “Peru's vibrant human rights community, which fought tirelessly to confront impunity, end the Fujimori dictatorship”

Peruvian precedent: the Fujimori conviction and the ongoing struggle for justice (2010). North American Congress on Latin America: NACLA Report on the Americas, vol.43 (p. 6). doi: 10.1080/10714839.2010.11722203 [HUB]- “the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (Court) ordered Peru to review the presidential pardon granted to former president and dictator Alberto Fujimori”

Inter-American Court of Human Rights – presidential pardon – anti-impunity – conventionality control (July 2019). American Journal of International Law, vol.113 (p. 568). doi: 10.1017/ajil.2019.28 [HUB] - “the dictator Fujimori fled”

La fiesta del Chivo, novel and film: on the transition to democracy in Latin America (Summer 2016). Latin American Research Review, vol.51 (pp. 85–100). doi: 10.1353/lar.2016.0035 [HUB] - “Fujimori's rule as a dictator lasted for nearly ten years”

Assessing Fujimori's Peru (2006). Georgetown Journal of International Affairs, vol.7 (p. 160). - “in Peru the first dictatorial support party was created by General Manuel Odria ... and the second completely different one by President Alberto Fujimori”

The legacy of dictatorship for democratic parties in Latin America (April 2016). GIGA Journal of Politics in Latin America, vol.8 (pp. 3–32). German Institute for Global and Area Studies. doi: 10.1177/1866802X1600800101 [HUB] - “former Peruvian dictator Alberto Fujimori often dressed as a samurai and as an Inca as part of his campaign publicity”

Why Asia and Latin America? (Fall 2017). University of Minnesota Press, vol.3 (p. 1). doi: 10.5749/vergstudglobasia.3.2.0001 [HUB] - "Leftist teacher takes on dictator's daughter as Peru picks new president" (2021-06-03).

- ↑ Charles D. Kenney, 2004 Fujimori's Coup and the Breakdown of Democracy in Latin America (Helen Kellogg Institute for International Studies) University of Notre Dame Press ISBN 0-268-03171-1

- ↑ Julio F. Carrion (ed.) 2006 The Fujimori Legacy: The Rise of Electoral Authoritarianism in Peru. Pennsylvania State University Press ISBN 0-271-02748-7

- ↑ Catherine M. Conaghan 2005 Fujimori's Peru: Deception in the Public Sphere (Pitt Latin American Series) University of Pittsburgh Press ISBN 0-8229-4259-3

- ↑ Esteban Cuya, La dictadura de Fujimori: marionetismo, corrupción y violaciones de los derechos humanos, Centro de Derechos Humanos de Nuremberg, July 1999. Retrieved 22 October 2006.

- ↑ Fujimori secures Japanese haven, BBC News, 12 December 2000. Retrieved 29 December 2007.

- ↑ "El "fujimorazo" y otros casos en América Latina que se comparan con la sentencia del Tribunal Supremo de Justicia de Venezuela sobre la Asamblea Nacional" (1 April 2017).

- ↑ ""Fujimorazo" y el golpe de Bordaberry: cómo fueron los antecedentes del "Madurazo" en Sudamérica" (30 March 2017).

- ↑ Hal Brands (2010). The United States and the Peruvian Challenge, 1968–1975. Diplomacy & Statecraft, vol.21 (pp. 471–490). Taylor & Francis. doi: 10.1080/09592296.2010.508418 [HUB]

- ↑ "Welcome, Mr. Peruvian President: Why Alan García is no hero to his people" (2 June 2010). Council on Hemispheric Affairs. Archived from the original on 18 April 2019.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 “the military's growing frustration over the limitations placed upon its counterinsurgency operations by democratic institutions, coupled with the growing inability of civilian politicians to deal with the spiraling economic crisis and the expansion of the Shining Path, prompted a group of military officers to devise a coup plan in the late 1980s. The plan called for the dissolution of Peru's civilian government, military control over the state, and total elimination of armed opposition groups. The plan, developed in a series of documents known as the "Plan Verde," outlined a strategy for carrying out a military coup in which the armed forces would govern for 15 to 20 years and radically restructure state-society relations along neoliberal lines.”

Jo-Marie Burt (1998). Unsettled accounts: militarization and memory in postwar Peru. NACLA Report on the Americas, vol.32 (pp. 35–41). Taylor & Francis. doi: 10.1080/10714839.1998.11725657 [HUB] - ↑ Freeman, Michael. Freedom Or Security: The Consequences for Democracies Using Emergency Powers. 2003, p. 150.

- ↑ Freeman, Michael. Freedom Or Security: The Consequences for Democracies Using Emergency Powers. 2003, p. 148.

- ↑ Freeman, Michael. Freedom Or Security: The Consequences for Democracies Using Emergency Powers. 2003, p. 159.

- ↑ "By the time Fujimori was elected you had a population in the cities, and particularly in Lima, that was living in fear." The Fall of Fujimori: Peru's war on terror 6 July 2006

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 “a government plan, developed by the Peruvian army between 1989 and 1990s to deal with the Shining Path insurrection, later known as the 'Green Plan', whose (unpublished) text expresses in explicit terms a genocidal intention”

Pierre Gaussens (2020). The forced serilization of indigenous population in Mexico in the 1990s. Canadian Journal of Bioethics, vol.3 (pp. 180+). doi: 10.7202/1073797ar [HUB] - ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 El "Plan Verde" Historia de una traición (12 July 1993). Oiga, vol.647.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 22.4 22.5 William Avilés (2009). Despite Insurgency: Reducing Military Prerogatives in Colombia and Peru. Latin American Politics and Society, vol.51 (pp. 57–85). Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1111/j.1548-2456.2009.00040.x [HUB]

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 23.4 “important members of the officer corps, particularly within the army, had been contemplating a military coup and the establishment of an authoritarian regime, or a so-called directed democracy. The project was known as 'Plan Verde', the Green Plan. ... Fujimori essentially adopted the 'Plan Verde,' and the military became a partner in the regime. ... The self-coup, of April 5, 1992, dissolved the Congress and the country's constitution and allowed for the implementation of the most important components of the 'Plan Verde.'”

Alfredo Schulte-Bockholt (2006). The politics of organized crime and the organized crime of politics: a study in criminal power: 'Chapter 5: Elites, Cocaine, and Power in Colombia and Peru' (pp. 114–118). Lexington Books. ISBN 9780739113585 - ↑ 24.0 24.1 Silvio Rendón (2013). La intervención de los Estados Unidos en el Perú (pp. 145–150). Editorial Sur. ISBN 9786124574139

- ↑ “a government plan, developed by the Peruvian army between 1989 and 1990s to deal with the Shining Path insurrection, later known as the 'Green Plan', whose (unpublished) text expresses in explicit terms a genocidal intention”

Pierre Gaussens (2020). The forced serilization of indigenous population in Mexico in the 1990s. Canadian Journal of Bioethics, vol.3 (pp. 180+). doi: 10.7202/1073797ar [HUB] - ↑ “The Plan Verde bore a striking resemblance to the government outlined by Fujimori in his speech on 5 April 1992. It called for a market economy within a framework of a 'directed democracy' that would be led by the armed forces after they dissolved the legislature and executive. ... The authors of the Plan Verde also stated that relations with the USA revolved more around the issue of drug trafficking than democracy and human rights, and thus made the fight against drug trafficking the number two strategic goal”

Maxwell A. Cameron (1998). Latin American Autogolpes: Dangerous Undertows in the Third Wave of Democratisation. Third World Quarterly, vol.19 (pp. 228–230). Taylor & Francis. doi: 10.1080/01436599814433 [HUB] - ↑ 27.0 27.1 “At the end of the 1980s, a group of military elites secretly developed an analysis of Peruvian society called El cuaderno verde. This analysis established the policies that the following government would have to carry out in order to defeat Shining Path and rescue the Peruvian economy from the deep crisis in which it found itself. El cuaderno verde was passed onto the national press in 1993, after some of these policies were enacted by President Fujimori. ... It was a program that resulted in the forced sterilization of Quechua-speaking women belonging to rural Andean communities. This is an example of 'ethnic cleansing' justified by the state, which claimed that a properly controlled birth rate would improve the distribution of national resources and thus reduce poverty levels. ... The Peruvian state decided to control the bodies of 'culturally backward' women, since they were considered a source of poverty and the seeds of subversive groups”

Racialization and Language: Interdisciplinary Perspectives From Perú (2018) (pp. 286–291). Routledge. - ↑ "Insight News TV | Peru: Fujimori's Forced Sterilization Campaign". Archived from the original on 6 January 2011.

- ↑ "Missing Page Redirect". www.cwnews.com.

- ↑ Peru Plans a Hot Line to Battle Forced-Sterilizations The ZENET Lima. Archived 2001-09-02

- ↑ "Mass sterilization scandal shocks Peru" (2002-07-24). BBC. Archived from the original on 2017-04-10.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 “the outlines for Peru's presidential coup were first developed within the armed forces before the 1990 election. This Plan Verde was shown to President Fujimori after the 1990 election before his inauguration. Thus, the president was able to prepare for an eventual self-coup during the first two years of his administration”

Latin American Autogolpes: Dangerous Undertows in the Third Wave of Democratisation (June 1998). Third World Quarterly, vol.19 (p. 228). Taylor & Francis. doi: 10.1080/01436599814433 [HUB] - ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 33.3 El "Plan Verde" Historia de una traición (12 July 1993). Oiga, vol.647.

- ↑ Gouge, Thomas. Exodus from Capitalism: The End of Inflation and Debt. 2003, page 363.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Gouge, Thomas. Exodus from Capitalism: The End of Inflation and Debt. 2003, p. 363.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 The Reagan Administration, the Cold War, and the Transition to Democracy Promotion (2018) (pp. 178–180). Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-3319963815

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 The Reagan Administration, the Cold War, and the Transition to Democracy Promotion (2018) (pp. 168–187). Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-3319963815

- ↑ The work of economics: how a discipline makes its world (2005). European Journal of Sociology, vol.46 (pp. 299–310). doi: 10.1017/S000397560500010X [HUB]

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 "A Peruvian Is Laying Out Another Path" (1990-11-27).

- ↑ The Globalist | Biography of Hernando de Soto Archived

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Gouge, Thomas. Exodus from Capitalism: The End of Inflation and Debt. 2003, p. 364.

- ↑ Heritage, Andrew (2002). Financial Times, World Desk Reference (pp. 462–465). ISBN 9780789488053

- ↑ La década de la antipolítica: auge y huida de Alberto Fujimori y Vladimiro Montesinos (2000) (p. 28). Instituto de Estudios Peruanos. ISBN 9972510433

- ↑ Fujimori's coup and the breakdown of democracy in Latin America (2004). University of Notre Dame Press. ISBN 0-268-03171-1

- ↑ Levitsky, Steven "Fujimori and Post-Party Politics in Peru", Journal of Democracy. 10(3):78

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 46.2 The Politics of Illusion: The Collapse of the Fujimori Regime in Peru (January 2018). Theatre Survey, vol.59 (pp. 84–107). doi: 10.1017/S0040557417000503 [HUB]

- ↑ Las Fuerzas Armadas y el 5 de abril: la percepción de la amenaza subversiva como una motivación golpista (1996) (pp. 46–47). Instituto de Estudios Peruanos.

- ↑ “the military's growing frustration over the limitations placed upon its counterinsurgency operations by democratic institutions, coupled with the growing inability of civilian politicians to deal with the spiraling economic crisis and the expansion of the Shining Path, prompted a group of military officers to devise a coup plan in the late 1980s. The plan called for the dissolution of Peru's civilian government, military control over the state, and total elimination of armed opposition groups. The plan, developed in a series of documents known as the "Plan Verde," outlined a strategy for carrying out a military coup in which the armed forces would govern for 15 to 20 years and radically restructure state-society relations along neoliberal lines.”

Unsettled accounts: militarization and memory in postwar Peru (September–October 1998). NACLA Report on the Americas, vol.32 (pp. 35–41). Taylor & Francis. doi: 10.1080/10714839.1998.11725657 [HUB] - ↑ "Decree Law 25418". Archived from the original on 2008-05-29.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 The Peruvian Press under Recent Authoritarian Regimes, with Special Reference to the self-coup of President Fujimori (2000). Bulletin of Latin American Research, vol.19 (pp. 17–32). doi: 10.1111/j.1470-9856.2000.tb00090.x [HUB]

- ↑ Stern, Steve J. Shining and Other Paths: War and Society in Peru, 1980–1995. 1998, p. 307.

- ↑ Ellen Perry's The Fall of Fujimori.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 53.2 53.3 Manzetti, Luigi. Privatization South American Style. 1999, p. 235.

- ↑ "Fujimori Resigns" (21 November 2000). The Irish Times.

- ↑ Benson, Sara and Hellander, Paul and Wlodarski, Rafael (2007). Lonely Planet (pp. 37–38).

- ↑ Mijail Mitrovic (2021). At the fabric of history: Peru's political struggle under (and against) the pandemic. Dialectical Anthropology, vol.45 (pp. 431–446). doi: 10.1007/s10624-021-09634-5 [HUB]

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 57.2 The Reagan Administration, the Cold War, and the Transition to Democracy Promotion (2018) (pp. 178–180). Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9783319963815

- ↑ "A Peruvian Is Laying Out Another Path" (1990-11-27).

- ↑ "New Peru Leader in Accord on Debt" (July 1990). The New York Times.

- ↑ "Corrupción, más allá de la ley. Serie Perú Hoy Nº 36 / Junio 2020". Desco.

- ↑ Peru, 31 October 1993: Constitution Direct Democracy

- ↑ National Security Archive (15 June 1995). "Fujimori signs amnesty law"

- ↑ The World Today Series: Latin America 2010 (2010). Stryker-Post Publications. ISBN 978-1-935264-12-5

- ↑ "Periodista peruano: A Fujimori le gustaba que lo llamaran "Chinochet"" (2 May 2014).

- ↑ David R. Mares (2001). Violent Peace: Militarized Interstate Bargaining in Latin America (pp. 161). Columbia University Press.

- ↑ Clifford Krauss, Peru's Chief to Seek 3rd Term, Capping a Long Legal Battle, New York Times, 28 December 1999. Retrieved 26 September 2006.

- ↑ Nohlen, D (2005). Elections in the Americas: A data handbook, Volume II (p. 454). ISBN 978-0-19-928358-3

- ↑ El Pacto Infame

- ↑ Fujimori's Peru: Deception in the Public Sphere (2006) (p. 55).

- ↑ Historieta de Venezuela: De Macuro a Maduro: 'La democracia pierde energía' (2018) (p. 142). Gráficas Pedrazas. ISBN 978-1-7328777-1-9

- ↑ The Peruvian Labyrinth (1997) (p. 216).

- ↑ Ulla D. Berg (2015). Mobile Selves: Race, Migration, and Belonging in Peru and the U.S. (p. 214). NYU Press. ISBN 978-1479896097

- ↑ State reform, coalitions, and the neoliberal 'autogolpe' in Peru (Winter 1995). Latin American Research Review, vol.30 (pp. 7–37). doi: 10.1017/S0023879100017155 [HUB]

- ↑ Fox, Elizabeth, and Fox, de Cardona and Waisbord, Silvio Ricardo. Latin Politics, Global Media. 2002, p. 154

- ↑ [1], BBC News, 18 September 2000. Retrieved 4 November 2006.

- ↑ “terruqueo, ou seja, a construção artificial, racista e conveniente de um inimigo sociopolítico para deslegitimar formas de protesto social”

A TOTALIDADE NEOLIBERAL-FUJIMORISTA: ESTIGMATIZAÇÃO E COLONIALIDADE NO PERU CONTEMPORÂNEO (2022). Revista Brasileira de Ciências Sociais, vol.37 (pp. e3710906). doi: 10.1590/3710906/2022 [HUB] - ↑ "Chile, Peru – How much do mining companies contribute? The debate on royalties is not over yet", Latinamerica Press, Special Edition – The Impact of Mining Latinamerica Press, Vol. 37, No. 2, 26 January 2005. ISSN 0254-203X. Accessible online as a Microsoft Word document. Retrieved 26 September 2006. There appears to be a separate HTML copy of the article on the site of Carrefour Amérique Latine (CAL). Retrieved 27 September 2006.

- ↑ "Peru: Public consultation says NO to mining in Tambogrande", pp.14–15 in WRM Bulletin # 59, June 2002 (World Rainforest Movement, English edition). Accessible online as Rich Text Format (RTF) document. Retrieved 26 September 2006.

- ↑ Jeffrey Bury, "Livelihoods in transition: transnational gold mining operations and local change in Cajamarca, Peru" The Geographical Journal (Royal Geographic Society), Vol. 170 Issue 1 March 2004, p. 78. Link leads to a pay site allowing access to this paper.

- ↑ "Investing in Destruction: The Impacts of a WTO Investment Agreement on Extractive Industries in Developing Countries", Oxfam America Briefing Paper, June 2003. Retrieved 27 September 2006.

- ↑ "A Backwards, Upside-Down Kind of Development": Global Actors, Mining and Community-Based Resistance in Honduras and Guatemala Archived, Rights Action, February 2005. Retrieved 27 September 2006.

- ↑ Arce, Moisés (2005). Market Reform in Society: Post-Crisis Politics and Economic Change in Authoritarian Peru. ISBN 978-0-271-02542-1

- ↑ "The shameful flight of Fujimori to Japan 15 years ago" (2015-11-08).

- ↑ "Fujimori Arrested in Chile: Peruvian FM" (2005-11-07). China Daily.

- ↑ The Earth Times, Peruvian government apologizes for 1992 massacre. 26 October 2007. Retrieved 22 April 2008.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 28 May 2008. Sentence in La Cantuta Case

- ↑ "Víctimas de las masacres de Barrios Altos y La Cantuta no eran terroristas" (7 April 2009). El Comercio. Archived from the original on 31 May 2015.

- ↑ "Condenan a Fujimori a 25 años de prisión por delitos de lesa humanidad" (7 April 2009). El Comercio. Archived from the original on 24 January 2014.

- ↑ "Alberto Fujimori es citado por Chile para declarar por esterilizaciones forzadas con miras a ampliar su extradición" (14 May 2023). infobae.

- ↑ "Peru: Former President Fujimori participates in forced sterilizations hearing" (19 May 2023). Andina.