More languages

More actions

| Argentine Republic República Argentina | |

|---|---|

Argentine territory in dark green; claimed but uncontrolled territory in light green. | |

| Capital and largest city | Buenos Aires |

| Official languages | Spanish |

| Demonym(s) | Argentine Argentinian |

| Dominant mode of production | Neocolonial capitalism |

| Government | Federal presidential republic |

• President | Javier Milei |

• Vice President | Victoria Villarruel |

| Area | |

• Total | 2,780,400 km² |

| Population | |

• 2022 census | 46,044,703 |

| Currency | Argentine peso |

Argentina, officially the Argentine Republic, is a country in Latin America located in the southern part of South America with a eastern coastline on the Atlantic Ocean. It is bordered to the west by Chile, to the north by Bolivia and Paraguay, and to the northeast by Brazil and Uruguay. It is currently under $44 billion of debt to the IMF.[1]

History[edit | edit source]

Pre-colonization[edit | edit source]

Before colonization, Argentina was home to various indigenous peoples.

The first recorded human settlement in Argentina dates back approximately 13,000 years, located on the southern tip of Patagonia. These early inhabitants were hunter-gatherers who are estimated to have settled around 10,000 BC and slowly spread throughout the land.[2]

The Tafí People (1000 - 500 BCE)[edit | edit source]

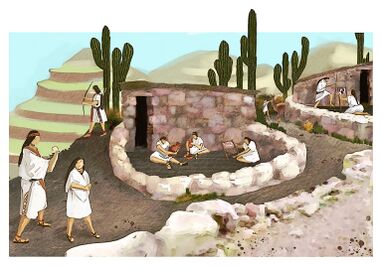

The Tafí people built interconnected villages with a unique cultural tradition, no house could be taller than another. This suggests an absence of class distinctions, as archaeologists have found no evidence of palaces, special housing for religious authorities, or signs of wealth accumulation. Furthermore, there are no signs that the Tafí were involved in any conflicts or wars, leading to the conclusion that they formed a relatively peaceful and egalitarian society. The Tafï had a complex spiritual life indicated by them building ceremonial structures such as menhirs and large communal enclosures.[3]

This structure functioned for hundreds of years. The Tafí cooperated and distributed wealth amongst themselves, developing an economy not based on hierarchy, a form of primitive communism. They maintained a sophisticated agricultural system, primarily growing corn and potatoes, and used llamas or guanacos to trade with nearby cultures. Notably, archaeological records show they built no fortifications, defensive structures, or walls. [4]

The Condorhuasi People (200 BCE - 500 CE)[edit | edit source]

The Condorhuasi people traveled and established a vast trade network and had a deep connection to rituals. They were situated in the Hualfin Valley and surrounding areas in Catamarca province. They built multiple ritual sites and were obsessed with transformation, as seen in their art depicting figures with multiple limbs, humans turning into animals, and gender-swapping. Their esoteric culture involved traditions of using psychedelics in rituals, accompanied by vivid imagery of animated stone beings and ancestors re-animated as stone creatures. They were highly artistic, leaving behind numerous esoteric ceramics and colorful, masked stone figures. They are considered the precursor of the La Aguada culture.[5]

The La Aguada People (500 - 900 CE)[edit | edit source]

Marking a sharp turn from previous peaceful cultures, the La Aguada people were known for their warlike imagery and detailed ceramics featuring dragons and decapitated remains. Despite their violent aspects, their dedication to craftsmanship was exceptional. Specific artisan groups created finely crafted copper and bronze objects, often featuring feline motifs and ceremonial items used to display the heads of enemies. They had a flourishing agricultural economy, growing beans, squash, peanuts, and corn in terraced fields irrigated by complex hydraulic systems. They also collected fruit from chañar and algarrobo trees and participated actively in extensive trans-andean trade networks. The La Aguada were skilled metalworkers who used the “lost wax” technique to create figures, axe heads, and decorative plates. These plates often depicted their symbolic universe, including a common motif known as the Deity of the Empty Hands, which possessed both feline and serpent attributes. They were also master potters, decorating vessels with elaborate incisions and pigments featuring geometric and mythical figures. The culture was led by a class of political and religious elites who governed independent clans, each based on a particular lineage. Despite sharing a common religious system, they likely had no central authority. Their complex funerary practices involved burial mounds with bodies arranged in relation to one another. The variation in grave goods points to clear differences in social status. La Aguada appears to be the first culture in the region to establish a rigid class structure and a patriarchal inheritance system, a logical development once wealth accumulation and its passage to descendants became important.[6]

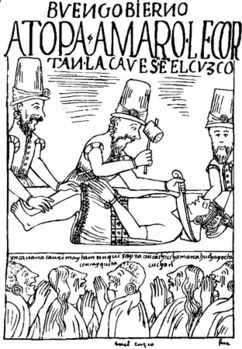

The Inca Empire (1438 - 1533 CE)[edit | edit source]

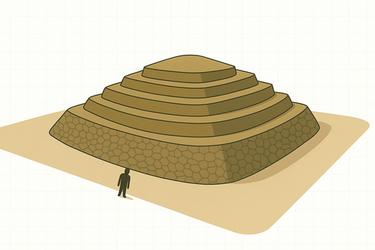

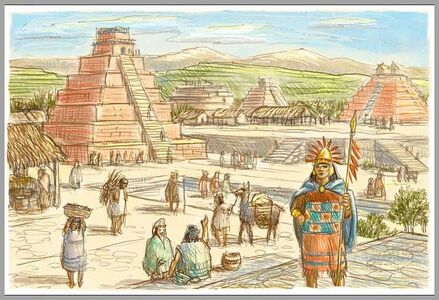

The most powerful and influential empire before the Spanish arrival, the Inca Empire had the most rigid and structured hierarchy of the pre-colonial societies and was a slave-based economy. Its class structure was a strict, four-tiered hierarchy. The Sapa Inca (emperor) was at the top, followed by the royalty and nobility (including blood relatives and privileged individuals like priests). Below them were the ayllu, the general populace of commoners such as farmers and artisans who provided labor and tribute. At the bottom were the yanaconas (slaves). The nobility enjoyed various privileges, including tax exemptions. The Inca ran a unique, non-monetary economy based on central planning, mandatory labor (mita), and reciprocal exchange within ayllu communities. Citizens provided labor for state projects in return for food, clothing, and shelter. The state managed agricultural production, collected surplus goods, and redistributed them across the empire to ensure basic needs were met for all citizens, though not for the slaves at the bottom of the social order. The Inca had massive infrastructure projects like the Qhapaq Ñan which was an extensive road network throughout the empire, storehouses and administrative centers like the Shincal de Quimivil and the famous Machu Picchu.[7]

Colonization[edit | edit source]

European Contact[edit | edit source]

Prior to European arrival, the region of modern-day Argentina supported an estimated 250,000 to one million people, comprising diverse cultures that were both nomadic and agrarian. The name "Argentina" itself originates from the Latin word for silver, argentum, inspired by rumors of a legendary silver mountain range. [8]

European contact began in 1516 with navigator Juan Díaz de Solís, who discovered the Río de la Plata while working for the Spanish Crown. However, while exploring the region, he and his men were killed by the Charrúa people, ensuring the expedition yielded no useful information for Spain. The key expedition was led by Sebastian Cabot between 1526 and 1530. His contact with the Guaraní, who gave him silver objects, fueled the specific rumor of a rich kingdom with a massive silver mountain. This sparked a race between Spain and Portugal to colonize the area. A Portuguese expedition in 1531 under Martim Afonso de Sousa aimed to reinforce Portugal's claim to the Americas under the Treaty of Tordesillas.[9]

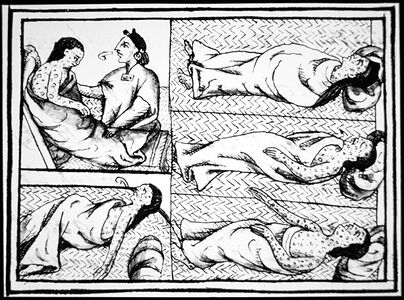

These initial contacts had a devastating, consequence with genocidal intent: the intentional introduction of European diseases, especially smallpox and the bubonic plague which would soon cripple the continent's greatest empires.[10]

The Conquest of the Inca Empire[edit | edit source]

See main article: Realm of the Four Parts (1438–1533)

The epidemic killed an estimated 80-90% of the native population, including the Inca Emperor Huayna Capac and his heir around 1528. This tragedy triggered a civil war between his sons, Atahualpa and Huáscar. Francisco Pizarro and his 200 men arrived at this perfect moment of profound weakness.[11]

A critical factor often omitted is the role of indigenous allies. The Inca Empire had recently subjugated many tribes, and groups like the Cañaris, Chankas, and Huancas saw the Spanish as liberators. Pizarro was thus joined by tens of thousands of warriors, forming a massive army that capitalized on widespread resentment against the Incas, though this was a grave mistake as the spanish proved to be extremely brutal compared to the Incas.[12]

Pizarro set a trap for the new emperor, Atahualpa, under the guise of a diplomatic meeting. The Spanish performed the Requerimiento, a legal formality demanding Catholic conversion to justify an attack. Since power in the Inca Empire was highly centralized, the subsequent kidnapping of Atahualpa decapitated the already fractured state.[13]

The conquest did not end with Atahualpa's capture. The Spanish installed a puppet ruler, Manco Inca, but after suffering abuse at the hands of the Pizarro brothers, he escaped and raised an army of 200,000 warriors. In 1536, he laid siege to the capital of Cuzco. For 40 years, Manco Inca and his successors waged a guerrilla war from the stronghold of Vilcabamba, killing hundreds of colonists, including Pizarro himself, and severely delaying the Spanish conquest.[14]

The Spanish resorted to brutal tactics to break the resistance, including targeting rebel leaders' families. They raped and murdered Manco Inca's sister-wife, using such atrocities to force concessions. The final blow came under Viceroy Francisco de Toledo, who launched a campaign to eradicate the independent Neo-Inca State. In 1572, Spanish forces and their indigenous allies razed Vilcabamba and captured the last Sapa Inca, Túpac Amaru. After a show trial, he was executed, and the mummified remains of past Sapa Incas were desecrated in front of him before his execution, symbolizing the final end of the empire.[15]

Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata & Peru[edit | edit source]

The fall of the Inca Empire enabled the full colonization of modern-day Argentina, funded by Inca wealth and powered by enslaved native labor. The region was first administered under the Viceroyalty of Peru and later the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata. The Spanish established oppressive systems designed to extract maximum wealth.[16]

The Encomienda was a labor system that "entrusted" non-Christian natives to colonizers, who were granted the right to demand tribute and labor in exchange for military protection and Christianization. In practice, it was slavery. Natives were forced to meet impossible quotas for tribute and starve or miss the quota and get abused while also being expected to work in deadly conditions, leading to mass mortality.[17]

The real killer was the silver mine at Potosí. Men, women, and children were forced into mercury mines, working 20-hour days for six months at a time. An estimated two to eight million Inca slaves died from mercury poisoning, exhaustion, disease, and suicide. The conditions were so horrific that African slaves were eventually brought in to replace the decimated native population.[18]

Viceroy Francisco de Toledo institutionalized this exploitation by repurposing the Inca Mit'a system. Originally a mandatory public service for state projects, Toledo twisted it into a forced labor draft. To manage it, he forced scattered villages into centralized towns called reducciones, making it easier to count people and select slaves for the mines. One-seventh of all adult men were forced to work in Potosí. The conditions were so brutal that many fled, creating a labor shortage that led mine owners to illegally extend shifts and intensify demands. A 2021 study provides evidence that this system caused an indirect genocide, leading to a catastrophic population collapse whose effects are still visible today.[19]

Independence[edit | edit source]

Argentina declared independence from Spain in 1821. It took a large loan from the British in 1824 and intended to use it to build infrastructure but spent most of it on a war with Brazil instead. The British seized two frigates from Argentina after they defaulted on their loan. Argentina finally finished repaying the loan in 1904.[20] During the early 20th century, the ruling class held its wealth in European banks and favored European currencies over the Argentine peso.[21]

Perón era[edit | edit source]

Argentina refused to join the neocolonial IMF when it was founded in 1945. Its democratically elected president, Juan Domingo Perón, followed a progressive nationalist program and improved industry through two five-year plans.[20] He bought the British-owned railroads.[21] Pedro Eugenio Aramburu overthrew Perón in a military coup in 1955 and joined the IMF.[20]

Operation Condor[edit | edit source]

In 1976, as part of Operation Condor, the CIA backed a far-right coup in Argentina that overthrew president Isabel Perón. After the coup, a military junta led by Jorge Rafael Videla took power and killed or disappeared 30,000 left-wing dissidents.[22] Under the junta, Friedmanites from the United States controlled Argentina's central bank.[20] In 1983, military rule ended, and Videla was given a life sentence for crimes against humanity in 1985.[23]

Recent history[edit | edit source]

Raúl Alfonsín was elected in 1983 following the end of the junta. His presidency ended with a hyperinflation crisis in 1989. He was succeeded by the conservative Carlos Menem. Menem pardoned members of the former junta and reduced taxes and business regulations. By 1990, the inflation rate was 20,000%. He pegged the Argentine peso to the U.S. dollar, oversaw mass privatization, and destroyed the country's extensive rail system.[20]

Between 1999 and 2001, liberal president Fernando de la Rúa continued to implement the IMF's austerity policies. A bank run began in November 2001, and de la Rúa limited withdrawals to $250 per person per week. Riots and a general strike followed, leading de la Rúa to flee the country on 20 December.[20] At the end of 2001, four presidents resigned within two weeks.[24]

Néstor Kirchner became president in 2003. Between 2003 and 2015, Argentina reduced poverty by 71% and extreme poverty by 81% and increased GDP per capita by 42%. Mauricio Macri, who came to power with U.S. support in 2015 and ruled until 2019, took a $57 billion loan from the IMF that led to 140% inflation and a 40% increase in poverty.[24] In February 2022, Argentina joined China's infrastructure program, the Belt and Road Initiative.[25] The areas of cooperation include green energy, technology, education, agriculture, communication, and nuclear energy.[26]

Milei presidency[edit | edit source]

In October 2023, the far-right libertarian Javier Milei was elected as Argentina's president. He seeks to abolish Argentina's central bank and replace its currency with the U.S. dollar.[24]

In December 2023, Milei announced the Decree of Necessity and Urgency and the Omnibus Law, allowing him to pass decrees without approval from Congress. His decrees have promoted foreign investment and privatize the economy. He cut diplomatic relations with Cuba and Venezuela, refused to join BRICS, and resumed talks with the IMF.[27]

On 24 January, 1.5 million workers went on a general strike. While Milei was visiting the Zionist Entity, the courts ruled to suspend his Omnibus Law.[27]

Economy[edit | edit source]

Argentina's debt is tied to the U.S. dollar, and it cannot print its own money.[20]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Ben Norton (2022-12-08). "Judicial coup in Argentina: Corrupt judges conspire with media oligarchs to ban Cristina Kirchner from office" Multipolarista. Archived from the original on 2022-12-09. Retrieved 2022-12-10.

- ↑ "Cueva de las Manos and associated sites of the Pinturas river basin" (2018-01-31). UNESCO.

- ↑ Rafa Burgos (2023-05-08). "The Tafí: a thousand years of peace and social equality in the Andes" EL PAIS.

- ↑ Great Soviet Encyclopedia (3rd ed.), vol. 2: 'Argentina' (1970) (Russian: Boljšaja sovjetskaja enciklopjedija). [PDF] Moscow.

- ↑ Benjamin Alberti (2024-03-01). "Stone Masks and Figurines from Northwest Argentina (500 BCE–650 CE)" MET MUSEUM.

- ↑ Museo Chileno de Arte Precolombino. "Southern Andes - La Aguada" Museo Chileno de Arte Precolombino.

- ↑ Father Bernabe Cobo (1979). History of the Inca Empire.

- ↑ Linda Newson (2008). The Demographic Impact of Colonization.

- ↑ Shumway, Nicolas (1991). The Invention of Argentina..

- ↑ Crosby, Alfred W. (1972). The Columbian Exchange: Biological and Cultural Consequences of 1492..

- ↑ Philip Ainsworth (1932). Fall of the Inca empire and the Spanish rule in Peru.

- ↑ María Rostworowski Tovar de Diez Canseco (2016). Mujer y poder en los Andes coloniales.

- ↑ R. Alan Covey (2023-7-19). The Fall of the Inca Empire.

- ↑ John Hemming (2004). The Conquest of the Inca.

- ↑ Pedro Sarmiento (1999). History of the Incas.

- ↑ Andresen, Earl R (2023). Foundation of the Viceroyalty of La Plata.

- ↑ Medeiros, Carmen. "COLONIAL LEGISLATIONS AS A FRAMEWORK FOR DISPOSSESSIONS IN THE CENTRAL ANDES: THE COLONIAL MITA" Dispossessions in the Americas.

- ↑ Kris Lane (2015-05-04). Potosí Mines.

- ↑ Miguel Angel Carpio (2021). Did the Colonial mita Cause a Population Collapse? What Current Surnames Reveal in Peru.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 20.4 20.5 20.6 Esteban Almiron (2022-12-18). "How Argentina has been trapped in neocolonial debt for 200 years: An economic history" Multipolarista. Archived from the original on 2022-12-19. Retrieved 2022-12-20.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Vijay Prashad (2008). The Darker Nations: A People's History of the Third World: 'Buenos Aires' (pp. 62–63). [PDF] The New Press. ISBN 9781595583420 [LG]

- ↑ Uki Goñi (2017-04-28). "40 years later, the mothers of Argentina’s 'disappeared' refuse to be silent" The Guardian. Retrieved 2022-01-01.

- ↑ Rosario Gabino (2008-10-10). "Argentina: Videla a la cárcel" BBC. Retrieved 2022-01-01.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 Janine Jackson, Mark Weisbrot (2023-11-28). "Milei Is ‘Really as Extreme as You Get in Right-Wing Libertarian Ideas’" FAIR. Archived from the original on 2023-11-29.

- ↑ "Argentina officially joins BRI in major boost for China-Latin America cooperation" (2022-02-06). Global Times. Retrieved 2022-02-08.

- ↑ Benjamin Norton (2022-02-12). "Trapped in IMF debt, Argentina turns to Russia and joins China's Belt & Road" Multipolarista.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Eduardo Rodriguez (2024-02-15). "Argentina is NOT for sale! Argentinians rise up against Milei’s neoliberal plunder" Liberation News. Archived from the original on 2024-02-24.